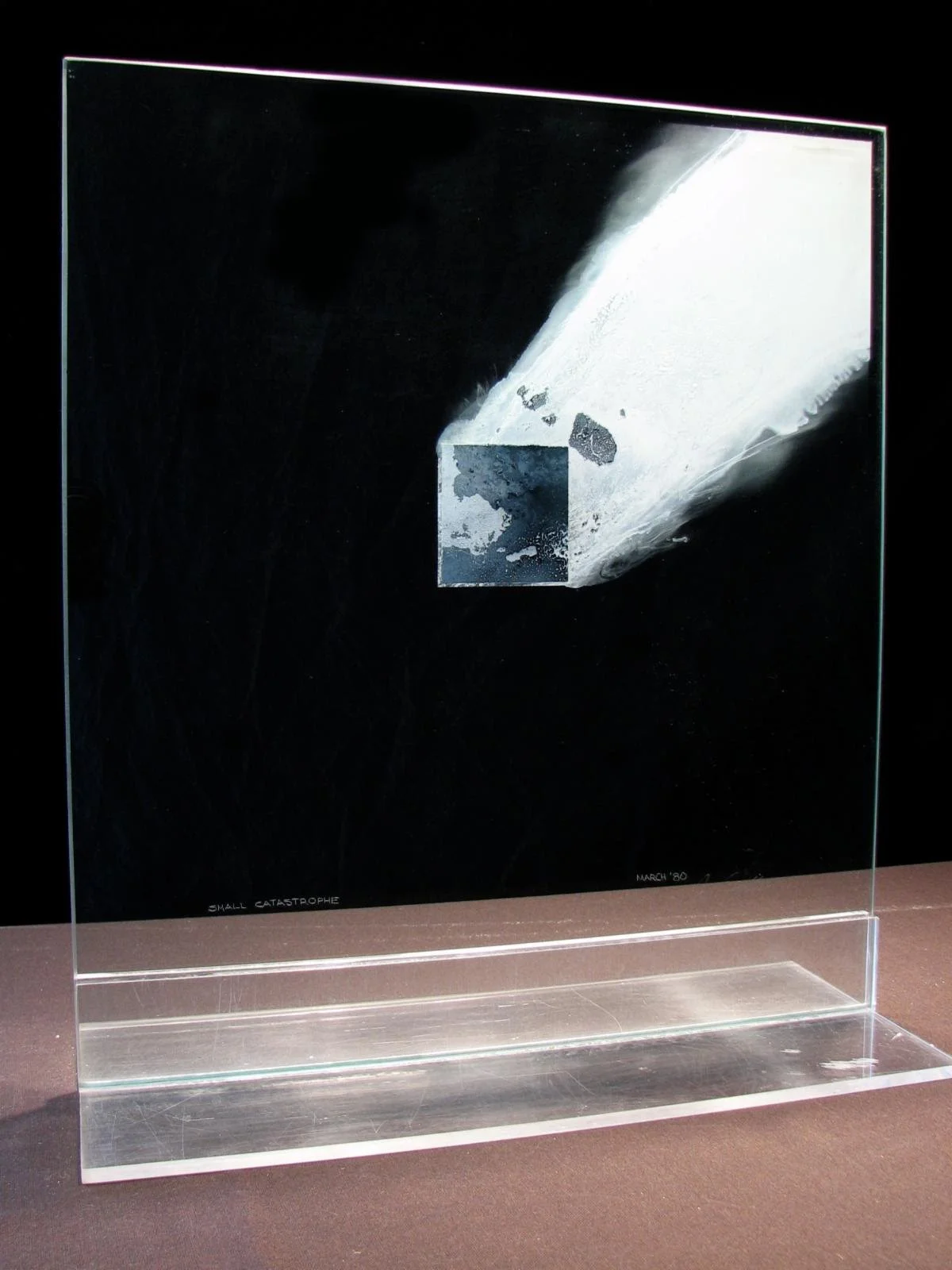

Small to show the big

“Small Catastrophe’’ (plate glass with vitreous enamels), by Eric Sealine, in his show “Drift and Flow: All the Time in the World,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery.

The gallery says that the show, from the artist's archive, is a series of “abstracted land, sea and skyscapes rendered on glass." Its ‘‘freestanding jewel-like pieces, while intimate in scale, mimic larger geologic, fluid, and erosional forces — from continental drifts, to cloud formations in the sky, to the patterns of sand on the shoreline.’’

Kate Petty: America is in a perilous reading recession, worsening our national attention-deficit disorder

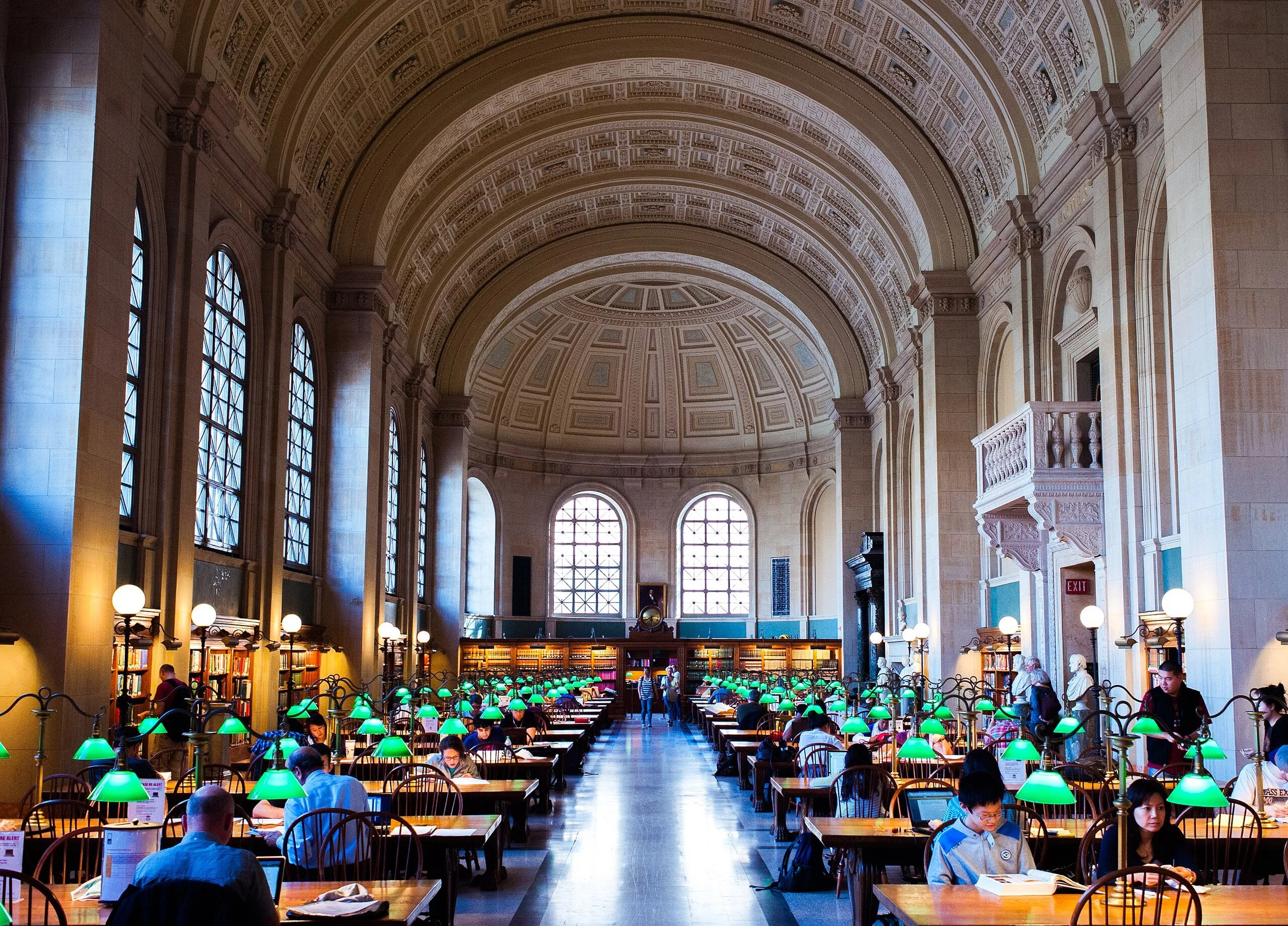

Bates Hall in the Boston Public Library’s McKim Building.

—Photo by Brian Johnson

The United States is in the grip of a reading recession—nearly half of Americans didn’t read a single book in 2023, and fewer than half read even one, according to data from YouGov and the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). Since the early 2000s, leisure reading has plunged by nearly 40 percent, a decline mirrored in falling reading scores and broader academic performance. What is at stake is not merely how people spend their free time, but a deeper erosion of the habits that sustain knowledge, empathy, and democratic life.

Decades of research show that the advantages of reading are both wide-ranging and profound. Regular engagement with books strengthens cognition, vocabulary, emotional intelligence, and empathy. These cognitive and social gains are closely linked to higher academic achievement, improved career prospects, greater economic stability, and increased civic engagement. Reading is one of the few activities that consistently bridges social divides—strengthening communities, encouraging civic participation, and sustaining democracy.

“The most important contribution of the invention of written language to the species is a democratic foundation for critical, inferential reasoning and reflective capacities,” writes cognitive neuroscientist and reading researcher Maryanne Wolf in her 2018 book Reader, Come Home. “If we in the 21st century are to preserve a vital collective conscience, we must ensure that all members of our society are able to read and think both deeply and well. … And we will fail as a society if we do not recognize and acknowledge the capacity for reflective reasoning in those who disagree with us.”

Literacy at Its Peak

Understanding the stakes of deep literacy today invites a look back at a time when reading was more than a pastime. More than a century ago, American writer and minister Gerald Stanley Lee captured reading’s transformative power in The Lost Art of Reading (1904): “The novel which gives itself to one to be breathed and lived… is the one which ‘gets a man somewhere’ most of all.”

Often described as America’s “golden age of reading,” the mid-20th century was a period when print media dominated daily life and literacy was widely cultivated across generations, supported by robust libraries, vibrant print journalism, and school curricula that treated reading as a central pillar of cultural participation.

According to NEA surveys, in the late 1940s, roughly 56–57 percent of adults read novels, short stories, poetry, or plays for pleasure. Daily newspaper readership was high, with about 65 percent of adults subscribing to or regularly reading newspapers, according to historical data from the Pew Research Center, while magazines such as Life, Time, and Reader’s Digest reached tens of millions of households.

Children and adolescents also read frequently outside of school, with 60–70 percent engaging in daily or near-daily reading, sustained by libraries, schools, and family practices, according to the National Literacy Trust. The period also saw the rise of shared reading experiences—fueled by organizations like the Book-of-the-Month Club and the Literary Guild—which broadened access to new titles, shaped national reading tastes, and helped make communal reading a mainstream cultural pastime.

The Data of Decline

By the early 2000s, national surveys were already signaling a decline in leisure reading in the United States. The NEA’s 2007 report “Reading at Risk: To Read or Not to Read: A Question of National Consequence” found that only 46.7 percent of adults read literature for pleasure, down from 54 percent a decade earlier.

Subsequent NEA surveys confirmed that the proportion of adults reading 12 or more books per year continued to fall. Gallup polls also reported a decline in the number of books read per year, from an average of 15.6 in 2016 to 12.6 in 2021. Time-use data from the American Academy of Arts & Sciences also shows that the share of Americans reading more than 20 minutes a day for personal interest dropped from 22.3 percent in 2003 to 14.6 percent in 2023.

Reading habits in the U.S. vary sharply by community type, income, and education. According to Pew (2021) and Library Research Service (2022), adults with higher education and income levels are far more likely to read regularly, while a 2011 Pew survey shows that rural residents lag behind urban and suburban peers, with fewer adults reporting reading for pleasure in the past year. Pew’s 2011 research found that 80 percent of urban and suburban adults read at least one book in the prior year, compared with 71 percent of rural adults, with significantly higher reading rates among college-educated and higher-income Americans than among less-educated and lower-income groups, revealing unequal cultural divides.

A landmark 2025 study published in iScience underscores the cultural shift reflected in declining reading habits. Tracking 236,270 individuals over two decades (2003–2023), the study examined both personal reading and reading with children and found that the share of U.S. adults reading for personal interest on an average day fell from roughly 28 percent in 2004 to 16 percent in 2023—a drop of about 12 percentage points.

“This is not just a small dip—it’s a sustained, steady decline of about 3 percent per year. It’s significant and it’s deeply concerning,” Jill Sonke, PhD, study co-author and director of research initiatives at the University of Florida Center for Arts in Medicine, said in a release about the study.

The research reveals a measurable, persistent, and accelerating trend in specific communities. In many of these households, children also have limited exposure to shared reading at home, further compounding early literacy gaps.

“Reading has always been one of the more accessible ways to support well-being,” said Daisy Fancourt, Ph.D., study co-author and professor of psychology and epidemiology at University College London. “To see this kind of decline is concerning because the research is clear: Reading is a vital health-enhancing behavior for every group within society, with benefits across the life-course.”

Lifelong Reading, Lifelong Benefits

Reading is a powerful tool for brain health, supporting cognitive function and emotional well-being throughout life. A 2009 study by the University of Sussex found that just six minutes of reading a day can reduce stress levels by up to 68 percent—more than listening to music or taking a walk—as well as lowering heart rate, reducing muscle tension, and improving sleep.

A 2020 study in International Psychogeriatrics found that consistent reading habits among older adults are associated with slower cognitive decline—independent of education and other risk factors. What’s more, a 2016 Social Science & Medicine study reported that book readers had roughly a 20 percent lower risk of death than non-readers.

As early as the mid-1940s, librarians and clinicians were documenting the use of reading as a therapeutic tool—a practice that came to be known as “bibliotherapy.” Case histories published in Library Journal, along with reports from psychiatric hospitals and educational settings, document how carefully chosen books could aid emotional healing, foster insight, and support rehabilitation.

Bibliotherapy is now practiced worldwide in public, academic, and hospital settings and is increasingly used by therapists as a mental-health support tool. As a 2025 BBC Future article notes, “Carefully selected books can provide emotional relief and help readers navigate difficult feelings, offering insights that might be hard to access otherwise.” An influential 2016 study published in Frontiers in Psychology found that engaging with literary fiction activates brain networks involved in social cognition, allowing readers to simulate other people’s thoughts and feelings, even when controlling for age, education, and IQ. “When readers engage with literary fiction, they actively simulate the experiences of others, enabling the use of social‑cognitive capacities in a way that non‑fiction simply does not,” the study notes. “If we become a nation of non-critical, superficial, shallow-skimming non-readers, we have no chance to build the base of empathy, critical analysis, and rigorous knowledge that is imperative for our next generation,” Reader, Come Home author Wolf said in an interview with the UCLA School of Education & Information.

The benefits begin early: A 2024 Psychological Medicine study of over 10,000 American children found that those who read early scored higher on cognitive tests and fared better emotionally as they entered adolescence. Yet many kids are missing out: A 2025 HarperCollins UK study reports that only 41 percent of kids ages 0–4 are read to regularly—a drop from 64 percent in 2012. The researchers note that Gen Z parents—many of whom grew up in the digital age—are more likely to see reading as academic rather than enjoyable. Nearly 30 percent say reading is “more a subject to learn than a fun thing to do,” compared with 21 percent of Gen X parents—and kids are following their lead: According to the study, 29 percent of children ages 5–13 now say reading feels like schoolwork, up from 25 percent in 2012.

“It’s very concerning that many children are growing up without a happy reading culture at home,” said Alison David, Consumer Insight Director at Farshore and HarperCollins Children’s Books, in a release about the study. “Children who are read to daily are almost three times as likely to choose to read independently compared to children who are only read to weekly at home.”

Early disparities in reading habits often persist into adulthood: American high school seniors are reading at lower levels than they have in over two decades, according to the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) report, which reveals a continuing long-term decline.

Low-Literacy, High Stakes

The stakes extend far beyond the classroom. Lesley Muldoon, executive director of the National Assessment Governing Board, warns, “These students are taking their next steps in life with fewer skills and less knowledge in core academics than their predecessors a decade ago, and this is happening at a time when rapid advancements in technology and society demand more of future workers and citizens, not less.”

Analysis from the 2023 Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) reveals a “dwindling middle” in skill distribution, with more Americans clustering at the bottom levels of proficiency than in previous assessments. According to the study, the share of adults performing at the lowest literacy level rose from 19 percent in 2017 to 28 percent in 2023, and fewer than half of adults now reach the highest proficiency levels.

Low adult literacy is estimated to cost the U.S. economy $2.2 trillion annually, factoring in lost productivity, higher healthcare spending, and other social costs, according to a 2021 Adult Literacy and Learning Impact Network study, which reports that more than half of American adults read at Level 2 or below, and nearly 30 percent struggle with the most basic texts, limiting job opportunities and career growth.

The Rise of Digital Media

Such widespread literacy challenges don’t exist in a vacuum—they collide with a rapidly changing media environment that makes deep reading even harder to sustain. In today’s “attention economy,” digital platforms feast on Americans’ media appetite, serving a constant menu of bite-sized, algorithm-curated news and “infotainment” via phones, tablets, and streaming feeds. As more Americans turn to gig work and experience growing time scarcity, sustained reading is increasingly squeezed out by the low-effort pull of online streaming—according to Pew Research, roughly 83 percent of U.S. adults turn to online streaming, revealing how both shrinking leisure time and intense competition for attention are driving the decline.

Pew Research shows that 86 percent of Americans now get news digitally, while only 7 percent rely on print newspapers. According to Pew’s Social Media and News fact sheet, about 53–54 percent of U.S. adults report getting news from social platforms at least sometimes. Facebook (38 percent) and YouTube (35 percent) remain the leading news sources, followed by Instagram (20 percent), TikTok (17 percent), and X/Twitter (12 percent). Streaming has also become deeply embedded in American culture, with 83 percent of adults reporting use of streaming services.

Reading is no longer just a solitary pastime—it faces increased competition from online communities, social media, and other digital distractions. The mid-20th-century “middlebrow” culture, where book clubs, newspapers, and mass-market fiction created shared cultural touchstones, has largely faded. As Thomas Jefferson warned, “An informed citizenry is the only true repository of the public will,” and yet being “well-read” no longer carries the social prestige it once did; literacy and engagement with books are less visible markers of cultural participation, reducing the societal incentives to read deeply or widely. This dramatic migration to digital formats is not merely a change in medium—it is transforming the cognitive and social contexts in which information is interpreted. The combination of fast-paced digital formats, viral misinformation, and partisan echo chambers amplifies skepticism, making it harder for audiences to distinguish reliable reporting from opinion or disinformation.

A 2025 Gallup survey reveals that Americans’ confidence in mass media has plunged to a historic low—just 28 percent now say they have “a great deal” or “a fair amount” of trust in newspapers, TV, and radio to report news “fully, accurately and fairly.” The survey notes that when it began polling in the 1970s, trust ranged from 68 percent to 72 percent.

Screen-Inferiority Effect

The move from print to screens represents a fundamental change in how Americans encounter reading content, sharpening concerns about how people, especially students, process what they read—and where they read it.

A growing body of research suggests that reading on screens can undermine comprehension, attention, and deep engagement compared with print. This phenomenon, dubbed the “screen inferiority effect,” appears to stem from three key issues: cognitive overload (digital reading encourages multitasking and scrolling), a lack of spatial landmarks (print’s physical layout helps our brains remember where information is on the page), and the tendency to skim when reading online.

Young readers may be the hardest hit. Research suggests that children who grow up with paper books not only score better on reading assessments but may also achieve more academically—those with access to physical books reportedly complete an average of three more years of education. MRI studies show that these children develop stronger neural connections in brain regions responsible for language and self-control—connections that screen-heavy kids may lack.

Leisure reading on digital platforms has also been linked to lower comprehension among children and young adults, according to a 2023 Scholastica review, and other long-term studies suggest that print reading fosters stronger retention and deeper cognitive processing, as reported by The Guardian.

A 2025 study published in Frontiers of Psychology examined how different modes of reading—paper, digital, audio, and video—affect cognition and mental health of college students, finding that participants who read literary works in paper (or listened in audio formats) showed the greatest improvements, demonstrating better cognitive function and lower levels of anxiety and depression than those in digital, video, or control groups.

“Reading has declined because it’s facing growing competition from other forms of media consumption that may offer students more immediate gratification,” Martin West, professor of education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the deputy director of the Program on Education Policy and Governance at the Harvard Kennedy School, noted in a 2025 “Harvard Thinking” podcast.

“I think we have a lot of evidence to support the extent to which technology can be a distractor when students are engaged in learning processes. And that ability to distract, to compete for attention, could also lead to diminished appetite for persistence in reading on their own,” said West.

The Literacy Divide

The challenge isn’t just attention—it’s the unraveling of support systems that sustain reading in schools, including rising book prices, unequal access, and weakened infrastructure, all of which are eroding opportunities for leisure reading and amplifying the economic pressures behind the decline. According to the Center for American Progress 2024 report “Investing in School Libraries and Librarians to Improve Literacy Outcomes,” more than 50 years of research show that students with access to well‑resourced school libraries with certified librarians consistently perform better academically and score higher on standardized assessments.

However, America’s public schools have quietly but steadily shed thousands of certified school librarians. A national analysis from the School Librarian Investigation—Divergence & Evolution (SLIDE) Project found that librarian positions dropped by about 20 percent between 2009 and 2019, even as many districts increased spending on other staff roles.

The losses were not evenly shared: High-poverty districts, schools serving mostly Black, Hispanic, or multilingual students, and small rural systems were far more likely to lose their certified librarians entirely. Charter schools were hit hardest: Roughly 90 percent reported having no librarians at all. The strain on school libraries reflects a broader crisis in the U.S. public library system, where staffing shortages, budget pressures, and reduced services are also concentrated in high-poverty, high-minority, and rural districts. A study published as an EdWorkingPaper finds that between 2008 and 2019, 766 public library outlets closed, disproportionately affecting rural areas; the closures were associated with declines in nearby students’ reading and math test scores.

Tests Over Texts

Access to books shapes not only what students can read but also how reading is taught. A growing emphasis on standardized testing has increasingly displaced literature, narrowing curricula to measurable skills and focusing on short texts and assessment at the expense of sustained reading or literary exploration. “A critical part of becoming a literate person is to examine and explore a full text. This should be a major part of every student’s education,” writes Peter Greene in “The Atomization of Literature: How Standardized Testing Is Killing Reading Instruction,” published in Forbes.

“Instead of teaching students how to read a whole book, we teach them how to take a standardized test,” Greene argues, adding, “As long as high-stakes testing pushes a quick, superficial solo reaction to a context-free excerpt, schools will deprioritize teaching reading and literacy as a reflective, collaborative, thoughtful deep dive into a complete work. And that will be a loss for students.”

Rose Horowitch, in her 2024 Atlantic article “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books,” cites a 2024 EducationWeek Research Center survey of about 300 third-to-eighth-grade educators, noting that only 17 percent said they primarily teach whole texts; an additional 49 percent combine whole texts with anthologies and excerpts. Horowitch emphasizes that nearly a quarter of respondents said that books are no longer the center of their curricula. “Whether through atrophy or apathy, a generation of students is reading fewer books,” writes Horowitch. “Students see reading books as akin to listening to vinyl records—something that a small subculture may still enjoy, but that’s mostly a relic of an earlier time.”

Counter-Currents: Signs of Hope

From smartphones to e-readers, new technology is beginning to erode the long-standing resilience of the paper book. About 30 percent of U.S. adults now read books digitally, according to the Pew Research Center. Audiobooks are experiencing even faster adoption: The Audio Publishers Association 2025 Consumer Survey found 51 percent of Americans aged 18 and older—an estimated 134 million people—have listened to an audiobook.

That momentum is matched—and in some ways surpassed—by the popularity of podcasts. Podcasting is booming in the U.S., reaching 210 million Americans and drawing 115 million weekly listeners as of 2025, according to Edison Research. Podcasting now accounts for roughly 11 percent of daily audio consumption, and over 1.1 million English-language podcast episodes have been identified via public RSS feeds.

One bright spot is that independent bookstores are experiencing a resurgence, often supported by local communities and curated events, and subscription book boxes make discovering new titles easier than ever. Social media, particularly TikTok’s “BookTok,” has become a powerful driver of reading among Gen Z, propelling interest in specific genres and bestselling titles. The growth of book‑subscription services suggests a counter-current supporting reading: the global market, valued at about $1.34 billion in 2024, is projected to nearly double by 2033, as more consumers seek curated deliveries to keep reading habits alive

The Path Ahead

To reverse the reading recession in the United States, experts say efforts need to reach across schools, families, and communities. “It will take a comprehensive ecosystem to support our students at every touchpoint,” says Dr. Paige Pullen, chief academic officer and literacy principal at the University of Florida’s Lastinger Center for Learning, in a releaseabout the innovative New Worlds Reading Initiative.

Created by the Florida Legislature in 2021, the program illustrates how multi-level, coordinated approaches can address declining reading rates. Offering modular training for educators from birth through 12th grade, incorporating evidence-based strategies, practical classroom applications, and ongoing mentorship, the initiative aims to support teachers in applying literacy practices in the classroom while promoting collaboration across schools and communities, helping ensure students receive consistent guidance in developing reading skills at each stage of learning.

Across the United States, several states are implementing ambitious literacy initiatives to address persistent reading gaps. Iowa, Arizona, Nebraska, Rhode Island, and Alaska have all received multi-million-dollar federal Comprehensive Literacy State Development (CLSD) grants to support evidence-based reading instruction, high-dose tutoring, and professional development for educators, with a focus on children in high-need communities. A range of literacy nonprofits and school programs are also stepping in to bolster reading skills and access to books, particularly for children in under-resourced communities.

The NEA offers a range of solutions to promote early reading at home—from in-clinic programs to digital tools and grassroots book-sharing initiatives. Nonprofits Reading Is Fundamental (RIF) and the Children’s Literacy Initiative are expanding access to books, supporting teachers, and strengthening reading instruction where schools need it most.

Raising a Reader partners with schools, community centers, and libraries to provide curated, multicultural book collections and training for parents. Reach Out and Read integrates literacy into pediatric care, giving books to young children during well-child visits and coaching caregivers on reading aloud together.

Worldreader—a global nonprofit that promotes family reading through its free digital app, BookSmart—is helping parents read to their children daily, even in low-resource settings.

Grants, policy incentives, and strategic partnerships are also critical to ensuring these efforts are sustainable and equitable. A policy brief from the Center for American Progress, “Investing in School Libraries and Librarians to Improve Literacy Outcomes,” argues that investing in certified school librarians, up-to-date collections, and teacher collaboration is a powerful lever to boost student literacy and long-term reading engagement.

Emerging technologies, such as augmented reality (AR technology) storybooks (Metabook) and interactive voice-assisted reading (TaleMate), combine engagement with learning, demonstrating how digital and print strategies can work together to foster reading habits, improve literacy outcomes, and transform libraries into immersive learning hubs.

Programs like Open eBooks—a collaboration among major publishers, libraries, and nonprofits—provide free access to thousands of eBooks for children in under-resourced communities. Penguin Random House’s Living Stories app merges read-aloud sessions with interactive lights and sounds to engage young readers. Library software providers like BiblioCommons integrate e-books into public library catalogs. At the same time, platforms such as Reading Plus and collaborations like Reading Partners + AT&T deliver personalized, digital literacy instruction to students at school and home.

Reversing America’s reading decline requires more than urging kids to pick up a book—it demands rebuilding a culture that champions literacy at every stage of life. This means addressing funding and staffing crises in school and public libraries, rethinking teaching practices that undervalue deep reading, and supporting parents in fostering early literacy. It also calls on policymakers, educators, and communities to invest in the long-term infrastructure that literacy requires.

The stakes are high: without intervention, the next generation risks inheriting a world of perpetual scrolling, fragmented attention, and shallow engagement with ideas. But with coordinated action, we can envision a future where books, both print and digital, reclaim their role as catalysts for curiosity, empathy, and civic understanding. Reading can once again be a shared cultural experience, a personal joy, and a cornerstone of an informed, connected society.

Kate Petty is an educator, writer, and environmental activist. She has worked with the New York Nature Conservancy and various United Nations initiatives, including UNICEF, the World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations, and the Universal Versatile Society to promote education, social justice, and solution-oriented projects for a healthier planet. She is a contributor to the Observatory.

This article was produced for the Observatory by the Independent Media Institute. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Why she lives there

Janet McTeer

— Photo by Siebbi

Lookout Point in Harpswell, Maine

“There's a reason I live in the Maine Woods, where nobody knows what I do for a living. I think you can be better if someone who's coming to see you perform has no idea who you really are.”

—Janet McTeer (born 1961) English actress. She’s been married to poet and fashion consultant Joseph Coleman since 2010. Mr. Coleman is also a registered Maine Guide.

When not in New York or elsewhere, Ms. McTeer lives in Harpswell, Maine, not exactly the “Maine Woods,’’ but rather a spiffy place on the coast with plenty of affluent summer people and folks linked to nearby Bowdoin College, in Brunswick. The Maine Coast has long drawn celebrities and rich people. The number has recently been rapidly increasing.

Statesmen are heavily outnumbered

James Freeman Clarke

“A politician thinks of the next election; a statesman of the next generation.’’

— James Freeman Clarke (181-1888), New England clergyman, theologian and author

At least no mosquitoes

“Morning Ice in December” (oil on canvas), by the late Severin Haines, from Collection of William and Dedee Shattuck, in show “Artistic Luminaries: Three Local Icons,’’ through Feb. 23 at the New Bedford Art Museum.

The museum explains:

{The} show celebrates “the careers of three friends and New Bedford art mainstays, Willoughby ‘Bill’ Elliott, Severin ‘Sig’ Haines and Marc St. Pierre. The three were “leading figures in the studios and classrooms of the Swain School of Design and the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth," and “their collective influence established a model of artistic and educational excellence that continues through successive generations of artists, remaining central to the South Coast’s creative identity.’’

Shark attack at B.U.

Outside B.U.’s Questroom School of Business, where the new SharkNinja lab will be housed.

Edited from a New England Council report.

“Boston University is partnering with SharkNinja to launch the SharkNinja AI & Analytics Lab, with the aim of merging academic insight with real-world business challenges for B.U. graduate students.

“The lab will be housed within Questroom’s Consulting Lab, where graduate students will work under faculty to design AI-driven solutions. Students will operate as a consulting team, using data-modeling techniques to support both hands-on product innovation and internal operations.

“‘We are here to help pore through large data sets to find those pockets of opportunity,’ said Peter Howard, executive director of Action Learning and the Questroom Consulting Lab.

‘“We’ll take on any type of challenge,’ he said. This initiative will give students the chance to apply their technical skills to high-impact projects while gaining direct decision-making experience.’’

Dramatic license

Detail from “Puppet Master,’’ by B. Lynch, in her show “Little Dramas,’’ at the Danforth Museum of Art, Framingham, Mass., through Jan. 11.

The museum says:

“Lynch has been working on this series for 13 years, and throughout, current events have shaped the way her creations develop and relate to one another. Her figures are darkly humorous, and slightly disarming, as using puppets to tell a story creates detachment in the viewer. The Reds exist in a fixed space, while her Grays hover in a somewhat vague past or future dystopia. These puppets are not meant to look realistic, they are playful and often a bit ridiculous; consequently, they ease the delivery of a difficult yet urgent contemporary message.’’

Michi Trota: The public pays a pile for Big Tech’s data centers

Servistar’s proposed huge data center in Westfield, Mass. It would require massive amounts of electricity.

The Massachusetts Green High Performance Computing Center, in Holyoke, a collaboration between several universities and corporate sponsors. including the University of Massachusetts, MIT, Harvard, Boston University, and Northeastern, and Dell ENC as well as Cisco.

Via OtherWords.org

Bill Gates recently made headlines by suggesting that climate change is no longer a priority, but the American public begs to differ.

In this last election, climate change was a defining issue in such states as Virginia and Georgia, where voters grappled with rising energy costs. And no matter how much tech billionaires try to distract us, increasing power costs and our worsening climate are directly connected to such corporations as Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon racing to dominate the AI landscape.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the price of energy has risen at more than twice the rate of inflation since 2020, and Big Tech’s push for more power-hungry data centers is only making it worse.

The data centers proliferating across the country drive up energy costs by powering energy-ravenous generative AI, cloud storage, digital networks, and other energy intensive programs — much of it fueled by coal and natural gas that exacerbate climate change.

In some cases, data centers consume enough electricity to power the equivalent of a small city. The wholesale price of electricity in areas housing data centers is up a whopping 267 percent from five years ago — and everyday customers are eating those costs.

Americans are also shouldering increasing costs of an extreme climate.

The Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard noted that insurance prices rose 74 percent between 2008 and 2024 — and between 2018 and 2023, nearly 2 million people had their policies canceled by insurers because of climate risks.

Meanwhile, home prices have gone up 40 percent in the past two decades — meaning that the cost of home repair and recovery from climate disasters has also grown, all while wages remain stagnant.

Data centers aren’t just putting our wallets at risk. Power grids across the country are already strained from aging infrastructure and repeated battering during extreme weather events.

The additional pressure to feed energy-intensive data centers only heightens the risk of power blackouts in such emergencies as wildfires, deep freezes, and hurricanes. And in some communities, people’s taps have literally run dry because data centers used all the local groundwater.

Worse still, Big Tech’s AI energy demand has triggered a resurgence in dirty energy with the construction of new gas-powered energy plants and delayed shutdowns of fossil fuel-powered plants. The tech industry is even pushing for a revitalization of nuclear energy, including the planned 2028 reopening of Three Mile Island — site of the worst nuclear power plant disaster in U.S. history — to help power Microsoft’s data centers.

Everyday people bear the costs of Big Tech’s hunger for profits. We pay it in rising energy bills, our worsening climate, our lack of access to safe water, increased noise pollution, and risks to our health and safety.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Instead of raising our bills, draining our local resources, and destabilizing our climate, Big Tech could create more energy jobs, lessen our power bills, and sustain communities.

We can demand that tech giants such as Microsoft, Meta, Google, and Amazon uphold their commitments to use 100 percent renewable energy and not rely on fossil fuels and nuclear energy to power data centers.

We can insist that data centers only go where they’re wanted by ensuring communities are given full transparency and protection in how they’re affected by power usage, water access, and noise pollution.

The current administration is ignoring its obligations to the American public by refusing to rein in Big Tech. But tech billionaires still have a responsibility to the very public they depend on for their existence.

Michi Trota is the executive editor of Green America.

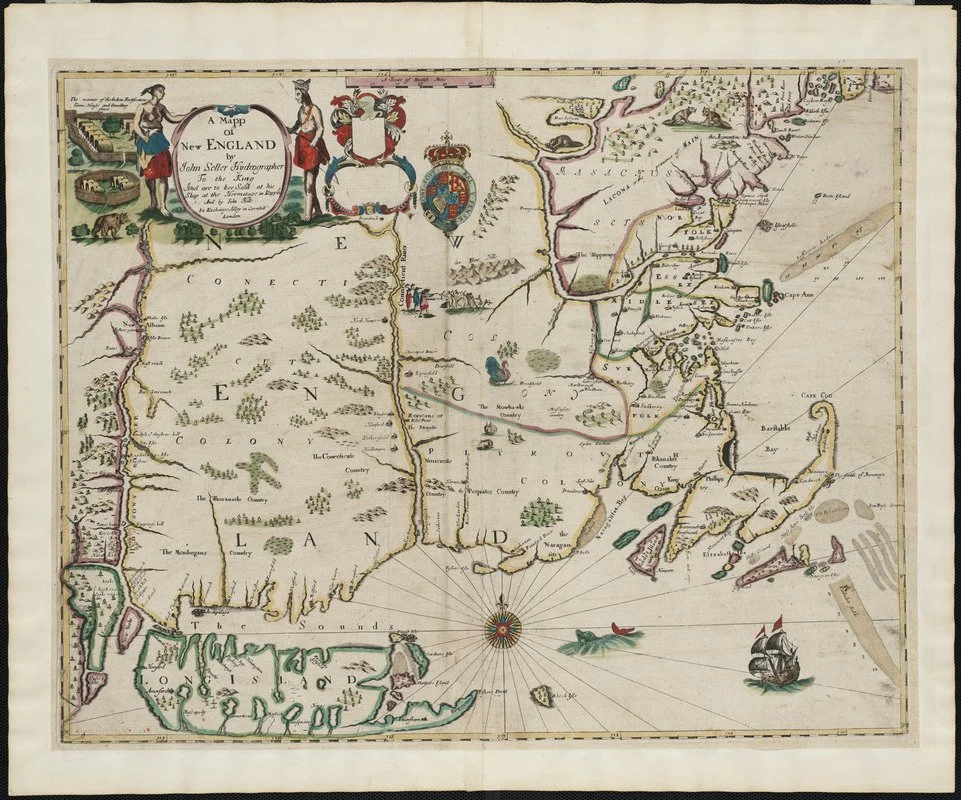

Those imaginative maps

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center Collection / Boston and New England Maps / Mapping Boston Collection

The center explains (we have edited slightly):

“This map is the firsy printed version of William Reed's original survey of 1665. The survey was commissioned by Massachusetts authorities to support the colonial boundaries as described in the first Massachusetts Charter of 1628. As originally proposed, the northern boundary was 30 miles north of the Merrimack River, assuming that the river followed an east-west course.

When it was later discovered that inland the Merrimack River turned north, Massachusetts colonists aggressively claimed lands 30 miles north of the river's source, an area also claimed by New Hampshire. The survey is the earliest to depict the relative position of the Hudson, Connecticut and Merrimack rivers. Also identified on the map are several towns that had been destroyed by Indians during the early months of King Philip's War.

Creator:

Fred D. Begley: How NIH became backbone of medical research and boosted U.S. innovation and economy

Bentley University Library, in Waltham, Mass.

From The Conversation, except for image above.

Fred D. Ledley is director of the Center for Integration of Science and Industry at Bentley University.

His research has been supported by grants to Bentley University from the Institute for New Economic Thinking, National Pharmaceutical Council, West Health, and the National Biomedical Research Foundation.

(Editor’s note: There are many NIH-linked facilities in New England.)

As a young medical student in 1975, I walked into a basement lab at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., to interview for a summer job.

It turned out to be the start of a lifelong affiliation – first as a trainee, then as a grantee running a university laboratory and finally, now, as a researcher of economics and public policy studying the agency’s impact on health care and on the national economy.

On that initial visit 50 years ago, I got my first direct experience with the NIH’s mission: to tap the enormous potential of basic science to improve human health and medical care. And over the long arc of my career, I watched the agency enact this mission in ways that brought enormous value to the country. NIH funding trained a legion of biomedical scientists, produced countless therapies that underpin much of modern medicine and catalyzed the launch of the biotechnology industry.

But widespread federal grant terminations and disruptions to federal funding in 2025 have left scientists who depend on NIH support reeling. And a 40% cut to the NIH budget for 2026 proposed by the White House threatens the agency’s future.

Origins and growth of the NIH

The NIH was founded through the Ransdell Act of 1930, which converted the former Hygienic Laboratory of the Marine Hospital Services into the seeds of a new government institution. That laboratory had been established in 1887 to develop public health measures, diagnostics and vaccines for controlling diseases prevalent in the U.S. at the time, such as cholera, yellow fever, smallpox, plague and diphtheria. With the act’s passage, the Hygienic Laboratory was reimagined as the National Institute of Health.

The NIH, initially called the National Institute of Health, was created in 1930 with the passage of the Ransdell Act. President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated the new NIH campus in Bethesda, Md., on Oct. 31, 1940, saying, ‘We cannot be a strong nation unless we are a healthy nation.’ National Institutes of Health

Sen. Joseph Ransdell of Louisiana envisioned the NIH as an agency with a broader mandate for translating scientific advances to improve human health. In arguing in 1929 for the creation of the new institute, he read into the Congressional Record an editorial from The New York Times that highlighted rapid advances in chemistry, physiology and physics.

The editorial lamented that “never in the whole history of the world had efforts to improve health conditions been behind the advance in other sciences.” Pointing to millions of Americans suffering from sickness leading to economic losses “into billions,” it argued for the need for a medical sciences institute coordinating “a national effort to prevent diseases that are or may be preventable.”

In 1945, a report called Science – The Endless Frontier, by Vannevar Bush, highlighted the government’s central role in supporting science that harnessed nuclear energy, implemented radar and developed penicillin – all important elements of the United States’ success in World War II. Bush argued that these wartime successes presented a model for growing the American economy, preventing and curing disease and projecting American power.

The NIH became central to this model. Its budget increased substantially during and just after World War II, with postwar adoption of Bush’s plan, and again after 1957 when the nation redoubled its commitment to science following Russia’s launch of Sputnik and the start of the space race. The National Cancer Act of 1971, which established the separate National Cancer Institute, reaffirmed the nation’s commitment to government-funded research. This new institute’s funding provided much of the seed capital for the emergence of biotechnology.

In the 1980s, the Stevenson-Wydler and Bayh-Dole acts created a clear pathway for developing commercial products from federally funded research that would provide public benefits and economic stimulus. These federal laws made it a requirement to pursue patenting and licensing of NIH-funded research to industry.

One project’s evolution reflects NIH’s mission

Today, the NIH represents the backbone of efforts to improve health and health care, supporting each step in the process from preliminary discovery to clinical advance. These steps correspond to the stages of an individual scientist’s path.

By putting study volunteers into a specially constructed metabolic chamber, NIH researchers in the 1950s could study how the human body uses air, water and food. The nurse here is affixing a hood onto a volunteer to measure oxygen consumption. National Institutes of Health

I experienced this progression in my own career. After establishing my first independent laboratory with a grant for early-stage researchers, then called a First Independent Research Support and Transition grant, a Research Project grant, widely known as an R01, funded my lab’s work identifying genes that cause inherited metabolic diseases in newborns. R01 grants are the main mechanism that academic biomedical scientists in the U.S. rely on to support innovative research.

Later, an NIH Program Project grant enabled us to investigate how the genes we had identified could be used to treat children. A General Clinical Research Center grant supported the hospital facilities necessary for clinical research and paid for patient care. Other grants supported our medical students and fellows as they embarked on their own careers as well as applications of our research to areas such as child health, reproductive biology and gastroenterology.

As our research on gene therapy progressed, NIH Small Business grants contributed to our founding a company that raised US$200 million in investments and partnerships and created hundreds of new jobs in Houston. Grants to small businesses continue to play a crucial role in helping universities commercialize discoveries.

Is the NIH effective?

For the past decade, I have led a research center focused on characterizing the process of developing new drugs. Our work, which is not funded by the NIH, shows that an established foundation of basic research on the biology underlying health and disease is necessary for successful drug development – and that most of this research is performed in public institutions.

We have found that NIH funding supported basic or applied research related to about 99% of newly approved medicines, clinical trials for 62% of these drugs and patents governing about 10% of these products.

Based on research conducted at the NIH, azidothymidine, or AZT, in 1987 became the first drug approved to treat AIDS. Here, the drug, added to the middle vial, protects healthy immune cells from being destroyed by HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. John Crawford, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health

Studies also show that this NIH funding saves industry almost $3 billion per drug in development costs. Over the past decade, there has been $800 billion in new investment in biotechnology. The U.S. biopharmaceutical industry directly supports more than 1 million jobs.

Medicines enabled by NIH funding have been crucial for increasing life expectancy and health – dramatically decreasing deaths due to heart disease and stroke, improving cancer outcomes, controlling HIV infection, improving the management of immunological diseases and easing the burden of psychiatric conditions.

The Trump administration is currently questioning the role of science in maintaining the nation’s health, economy and global posture. Yet the NIH stands as a testimony to the vision articulated by its early architects.

At its heart is the conviction that science is good for society, that persistent investment in basic research is essential to technological advances that serve the public interest, and that our nation’s health and economy benefit from developments in biology.

Before fading away

“Old Soldier” (oil on canvas), by Jean Jack, at Portland Art Gallery.

The gallery says:

“Jean Jack is a Maine-based fine artist whose iconic paintings of barns and farmhouses explore the quiet dignity of rural American architecture. Her work blends abstraction and realism, often featuring solitary structures placed within simplified landscapes that evoke a powerful emotional response. Known for capturing a distinct ‘sense of place,’ Jean’s compositions highlight the interplay between form, shadow, and space.’’

A big padded cell

Barnstable Harbor, as seen from Millway Beach.

— Photo by ToddC4176

“I had a large house {in Barnstable, Mass.} with lots of kids in it — three of my own and three adopted. And Cape Cod was a padded cell where children couldn’t possibly hurt themselves when they were growing up.’’

— Kurt Vonnegut Jr. (1922-2007), American novelist

The Goodspeed House, in Barnstable. It was built in 1653.

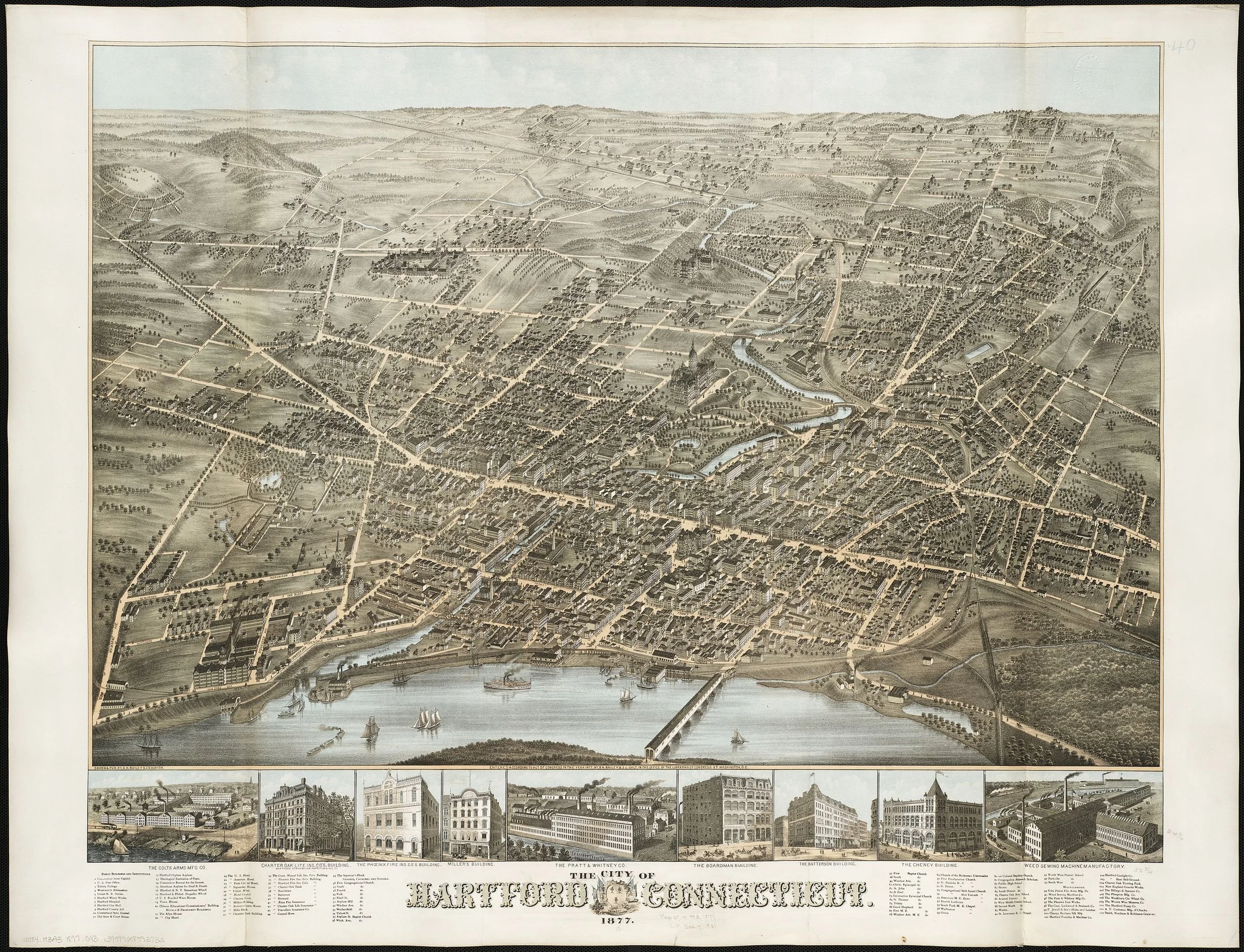

Chris Powell: In Hartford, a promising way to address the housing shortage

Hartford from the air.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

State government and Hartford city government have figured out the easiest way to solve Connecticut's desperate shortage of inexpensive housing. They just haven't quite realized that they have figured it out.

The solution was presented at City Hall the other week by Mayor Arunan Arulampalam and Gov. Ned Lamont, who announced a $4 million project funded jointly by the state and the city through what is called the Connecticut Home Funds initiative. The project is to turn 18 blighted and abandoned residential properties, condemned by the city long ago, into 20 units of new, owner-occupied housing.

The properties are to be sold to builders for $1 each and the program will help them finance construction. The builders will be required to sell the new houses to people of moderate income at a price that will permit them to be mortgaged for a monthly payment close to the neighborhood's apartment rents. The program aims to increase Hartford's homeownership rate, the lowest in the state at only 23 percent.

The price control involved, while likely to be popular, may be tricky to manage and is mistaken anyway, since it aims to prevent “gentrification" even as Hartford, terribly poor, needs many more residents with higher incomes.

The program's selection of builders also may be troublesome since it is likely to be heavily influenced by political patronage.

But then Connecticut is a one-party state, much in its government is contaminated by patronage, and advocacy of the public interest is so weak here that it's hard to accomplish anything good without patronage.

What is crucial about the Hartford project is its hint that the best way to alleviate the housing shortage isn't to fiddle with zoning regulations and state financial incentives to municipalities but simply to build housing wherever it can be built without aggravating the neighbors too much.

Hartford is hardly alone in being full of dilapidated and underused properties. Connecticut is pockmarked not just with deteriorating tenements but also vacant former factories and commercial buildings. Many city office buildings are half vacant as well now that so many people work from home via the Internet.

Most of these properties would be infinitely more beneficial and attractive to their neighborhoods if replaced by new housing, single- or multi-family, or converted to mixed commercial and residential use -- so much more beneficial and attractive that even the worst snobs might not mind new people moving into town to replace the eyesores. Most of these properties are already served by water, sewer, and utility lines, so housing construction would not chew up the countryside with more suburban sprawl.

But transforming dilapidated and underused properties into the housing that Connecticut needs won't meet the urgency of the moment unless, as Hartford has done, government gains control of the properties and clears the way to their replacement.

No builder or developer wants to spend months or years haggling with a zoning board and pretty-pleasing the neighbors, just as no one who needs housing -- including the children of the very people who object to new housing nearby -- wants to wait months or years for a decent home he can afford.

So addressing the housing shortage with the necessary urgency is a matter of identifying the properties where any housing would be better than leaving the properties as they are. That approach might create more housing in a year than the housing law that Connecticut enacted this year after such controversy.

So an amendment to that law is in order. The law authorizes the state Housing Department to build housing on state government property. The department also should be authorized to condemn and take control of decrepit or abandoned properties anywhere in the state and arrange construction of housing there, and to solicit municipalities to recommend such properties for conversion.

Connecticut has many places where any housing would be better than leaving things as they are. Identify them, level them, build housing on them, and bring housing prices down along with the state's high cost of living.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Hartford in 1877.

No need to walk three times a day

“D-g Days” (carved wood, relief on fabric, paint), by Eva Strum Gross, in a group show called “Novel Formats,’’ opening Jan. 16 at AVA Gallery and Art Center, Lebanon, N.H.

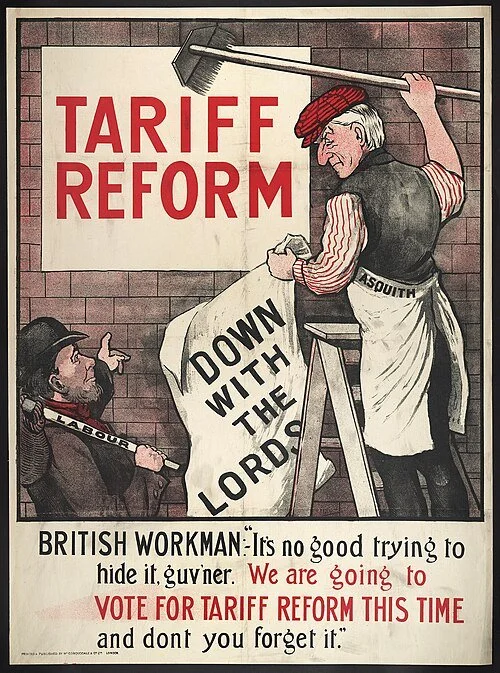

Kent Jones: The taxes that are called tariffs — some history and who gets hit

Cartoon from around 1900.

From The Conversation (except for images above)

Kent Jones is a professor emeritus of economics at Babson College, Wellesley, Mass.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The U.S. Supreme Court is currently reviewing a case to determine whether President Donald Trump’s global tariffs are legal.

Until recently, tariffs rarely made headlines. Yet today, they play a major role in U.S. economic policy, affecting the prices of everything from groceries to autos to holiday gifts, as well as the outlook for unemployment, inflation and even recession.

I’m an economist who studies trade policy, and I’ve found that many people have questions about tariffs. This primer explains what they are, what effects they have, and why governments impose them.

Who pays them?

Tariffs are taxes on imports of goods, usually for purposes of protecting particular domestic industries from import competition. When an American business imports goods, U.S. Customs and Border Protection sends it a tariff bill that the company must pay before the merchandise can enter the country.

Because tariffs raise costs for U.S. importers, those companies usually pass the expense on to their customers by raising prices. Sometimes, importers choose to absorb part of the tariff’s cost so consumers don’t switch to more affordable competing products.

However, firms with low profit margins may risk going out of business if they do that for very long. In general, the longer tariffs are in place, the more likely companies are to pass the costs on to customers.

Importers can also ask foreign suppliers to absorb some of the tariff cost by lowering their export price. But exporters don’t have an incentive to do that if they can sell to other countries at a higher price.

Studies of Trump’s 2025 tariffs suggest that U.S. consumers and importers are already paying the price, with little evidence that foreign suppliers have borne any of the burden. After six months of the tariffs, importers are absorbing as much as 80% of the cost, which suggests that they believe the tariffs will be temporary. If the Supreme Court allows the Trump tariffs to continue, the burden on consumers will likely increase.

While tariffs apply only to imports, they tend to indirectly boost the prices of domestically produced goods, too. That’s because tariffs reduce demand for imports, which in turn increases the demand for substitutes. This allows domestic producers to raise their prices as well.

A brief history of tariffs

The U.S. Constitution assigns all tariff- and tax-making power to Congress. Early in U.S. history, tariffs were used to finance the federal government. Especially after the Civil War, when U.S. manufacturing was growing rapidly, tariffs were used to shield U.S. industries from foreign competition.

The introduction of the individual income tax in 1913 displaced tariffs as the main source of U.S. tax revenue. The last major U.S. tariff law was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which established an average tariff rate of 20% on all imports by 1933.

Those tariffs sparked foreign retaliation and a global trade war during the Great Depression. After World War II, the U.S. led the formation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, or GATT, which promoted tariff reduction policies as the key to economic stability and growth. As a result, global average tariff rates dropped from around 40% in 1947 to 3.5% in 2024. The U.S. average tariff rate fell to 2.5% that year, while about 60% of all U.S. imports entered duty-free.

While Congress is officially responsible for tariffs, it can delegate emergency tariff power to the president for quick action as long as constitutional boundaries are followed. The current Supreme Court case involves Trump’s use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, or IEEPA, to unilaterally change all U.S. general tariff rates and duration, country by country, by executive order. The controversy stems from the claim that Trump has overstepped his constitutional authority granted by that act, which does not mention tariffs or specifically authorize the president to impose them.

The pros and cons of tariffs

In my view, though, the bigger question is whether tariffs are good or bad policy. The disastrous experience of the tariff war during the Great Depression led to a broad global consensus favoring freer trade and lower tariffs. Research in economics and political science tends to back up this view, although tariffs have never disappeared as a policy tool, particularly for developing countries with limited sources of tax revenue and the desire to protect their fledgling industries from imports.

Yet Trump has resurrected tariffs not only as a protectionist device, but also as a source of government revenue for the world’s largest economy. In fact, Trump insists that tariffs can replace individual income taxes, a view contested by most economists.

Most of Trump’s tariffs have a protectionist purpose: to favor domestic industries by raising import prices and shifting demand to domestically produced goods. The aim is to increase domestic output and employment in tariff-protected industries, whose success is presumably more valuable to the economy than the open market allows. The success of this approach depends on labor, capital and long-term investment flowing into protected sectors in ways that improve their efficiency, growth and employment.

Critics argue that tariffs come with trade-offs: Favoring one set of industries necessarily disfavors others, and it raises prices for consumers. Manipulating prices and demand results in market inefficiency, as the U.S. economy produces more goods that are less efficiently made and fewer that are more efficiently made. In addition, U.S. tariffs have already resulted in foreign retaliatory trade actions, damaging U.S. exporters.

Trump’s tariffs also carry an uncertainty cost because he is constantly threatening, changing, canceling and reinstating them. Companies and financiers tend to invest in protected industries only if tariff levels are predictable. But Trump’s negotiating strategy has involved numerous reversals and new threats, making it difficult for investors to calculate the value of those commitments. One study estimates that such uncertainty has actually reduced U.S. investment by 4.4% in 2025.

A major, if underappreciated, cost of Trump’s tariffs is that they have violated U.S. global trade agreements and GATT rules on nondiscrimination and tariff-binding. This has made the U.S. a less reliable trading partner. The U.S. had previously championed this system, which brought stability and cooperation to global trade relations. Now that the U.S. is conducting trade policy through unilateral tariff hikes and antagonistic rhetoric, its trading partners are already beginning to look for new, more stable and growing trade relationships.

So what’s next? Trump has vowed to use other emergency tariff measures if the Supreme Court strikes down his IEEPA tariffs. So as long as Congress is unwilling to step in, it’s likely that an aggressive U.S. tariff regime will continue, regardless of the court’s judgment. That means public awareness of tariffs – and of who pays them and what they change – will remain crucial for understanding the direction of the U.S. economy.

When people are gone

“Station/Frankfurt” (detail) (acrylic on panel), by Peter Waite, in his show “Social Memory, Paintings 1987-2025,’’ at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Conn.

The museum says:

“What if absence were a presence? Peter Waite is known for his large-scale architectural scenes that explore spaces where history, memory, and perception meet. Working in acrylic on rigid panels, Waite’s compositions capture the beauty and poignancy of overlooked corners, faded surfaces, and traces of life that remain when people are gone.’’

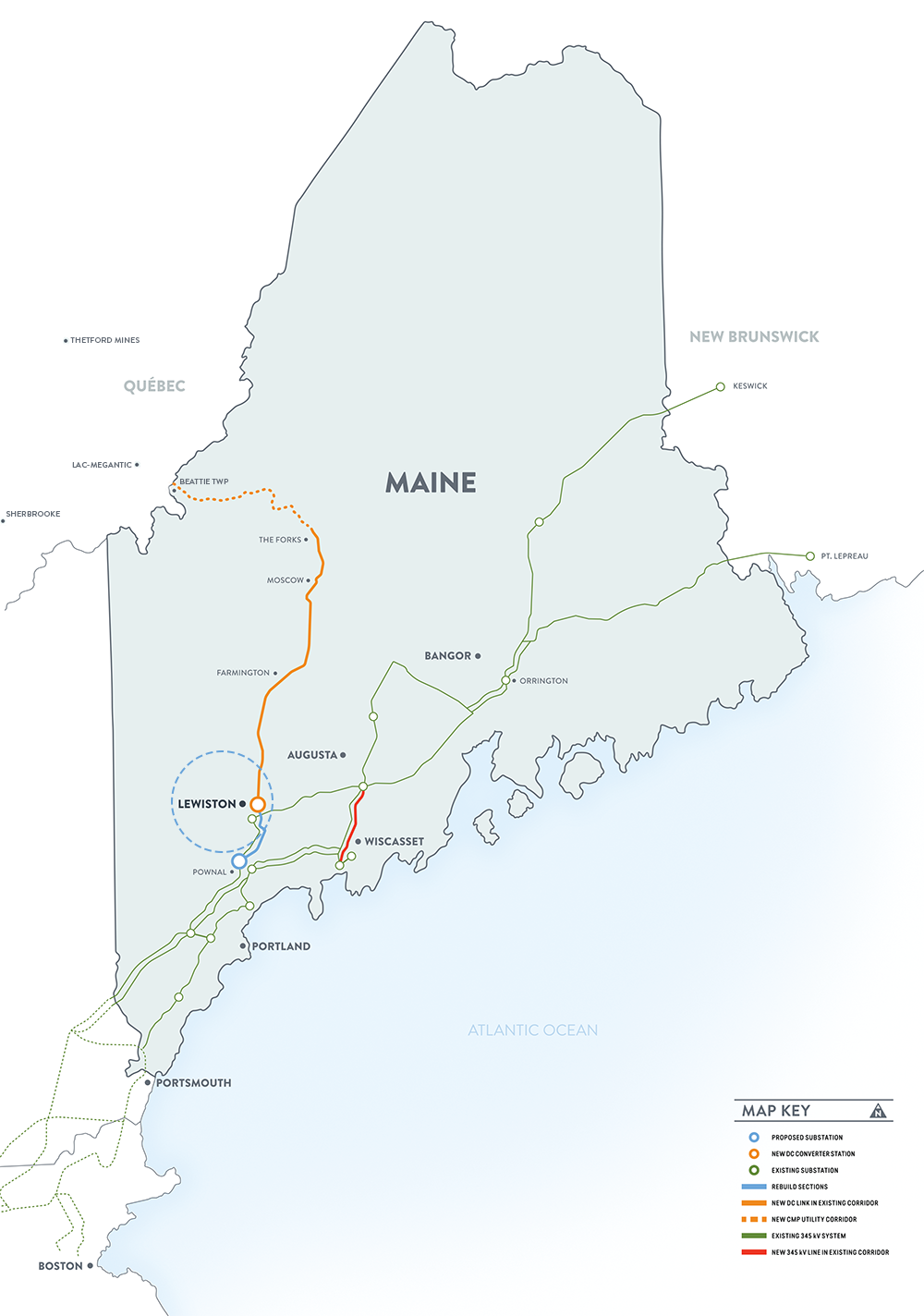

Trump hasn’t killed this one

Edited from a New England Council report

Avangrid announced recently that it has received the last permit needed to begin operation of New England Clean Energy Connect, a 145-mile transmission line that has been in the works for eight years.

The New England Clean Energy Connect has a high-voltage transmission line from Quebec to Lewiston, Mainem, that connects the New England grid to 1,200 megawatts of hydropower from Canada. Avangrid and Central Maine Power are set to have the connection energized very soon.

“This milestone marks the last regulatory step in a rigorous, multi-year process and clears the path for full completion of one of the largest, most transformative energy projects in the region,” Avangrid said in a release. CEO Jose Antonio Miranda emphasized the importance of the project: “We have secured every permit, met every regulatory requirement, and overcome significant challenges because we believe we must address the urgent need for reliable energy at a time of rising demand.”

Reminders of death and life

Macro photo of a snowflake

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

After a day of cold rain last week, amidst the season’s deepening darkness, the sun came out to remind us that in a couple of weeks the days will start getting longer again. Meanwhile some seed catalogs are in the mail.

But snowflakes must fall – trillions of them, and to think that each looks different up close! (I see snowfall as a reminder of the shroud of death on a cloudy day and as a celebration of light and therefore of life on a sunny one.)

The coming of winter-storm season reminds me of the irritating demand that people show up to work at the newspapers where I labored regardless of the weather. In my case most memorable was trudging and climbing home from The Providence Journal in the Blizzard of ’78 and walking home as branches were still falling during the tail end of Hurricane Bob in 1991.

But as the great English playwright, songwriter and director Noel Coward asked: “Why Must the Show Go On?’’ Here’s the song.

xxx

I have fond memories from childhood of visiting what’s now called the Edaville Historic Train & Festival of {holiday} Lights, whose origins go back to 1947. It’s magical place (at least for children) in South Carver, Mass. in the heart of Cranberry Country. Check it out.

At this time of year, any place with bright lights, colored or just white, is much appreciated.