Kate Petty: America is in a perilous reading recession, worsening our national attention-deficit disorder

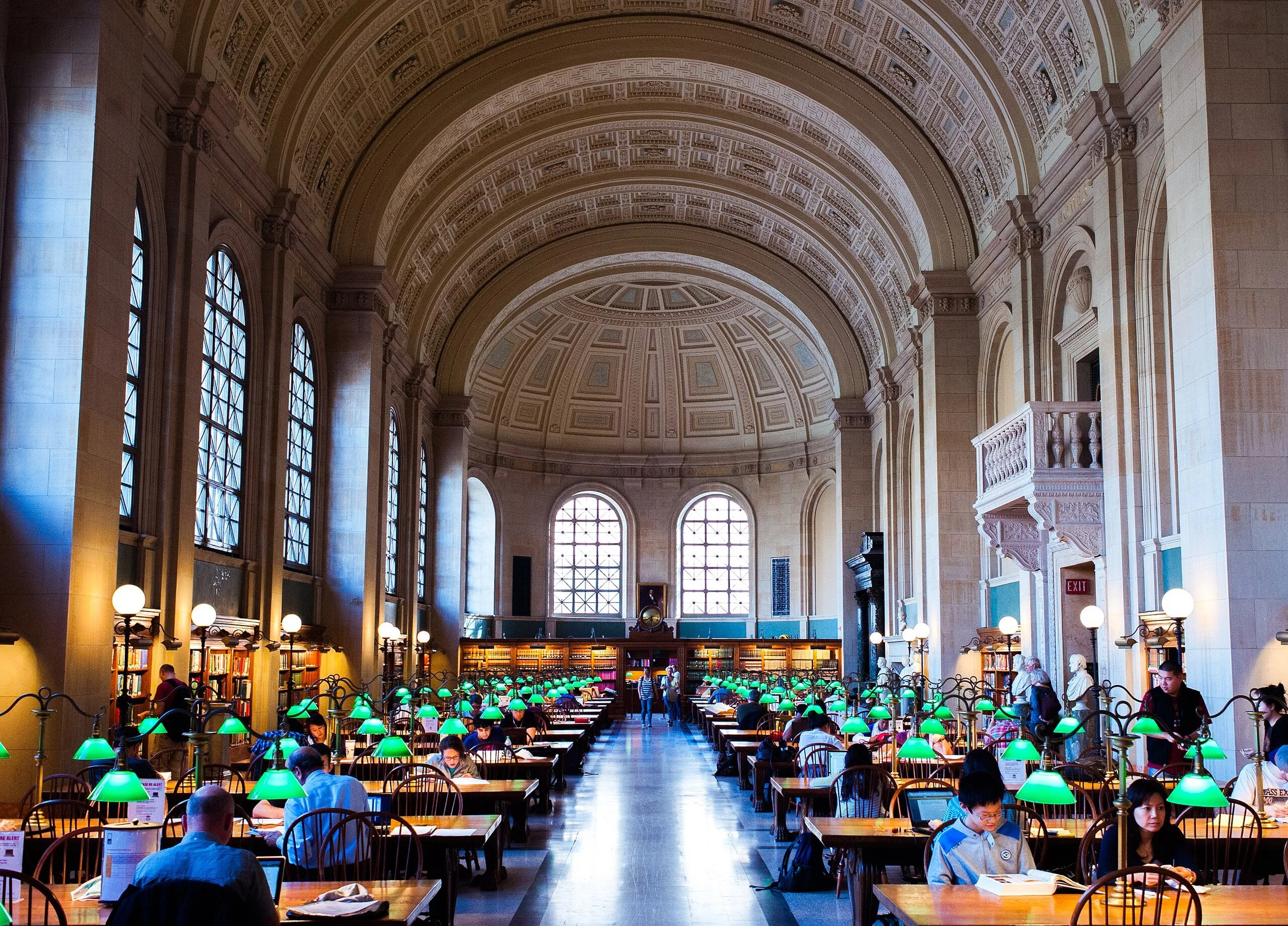

Bates Hall in the Boston Public Library’s McKim Building.

—Photo by Brian Johnson

The United States is in the grip of a reading recession—nearly half of Americans didn’t read a single book in 2023, and fewer than half read even one, according to data from YouGov and the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). Since the early 2000s, leisure reading has plunged by nearly 40 percent, a decline mirrored in falling reading scores and broader academic performance. What is at stake is not merely how people spend their free time, but a deeper erosion of the habits that sustain knowledge, empathy, and democratic life.

Decades of research show that the advantages of reading are both wide-ranging and profound. Regular engagement with books strengthens cognition, vocabulary, emotional intelligence, and empathy. These cognitive and social gains are closely linked to higher academic achievement, improved career prospects, greater economic stability, and increased civic engagement. Reading is one of the few activities that consistently bridges social divides—strengthening communities, encouraging civic participation, and sustaining democracy.

“The most important contribution of the invention of written language to the species is a democratic foundation for critical, inferential reasoning and reflective capacities,” writes cognitive neuroscientist and reading researcher Maryanne Wolf in her 2018 book Reader, Come Home. “If we in the 21st century are to preserve a vital collective conscience, we must ensure that all members of our society are able to read and think both deeply and well. … And we will fail as a society if we do not recognize and acknowledge the capacity for reflective reasoning in those who disagree with us.”

Literacy at Its Peak

Understanding the stakes of deep literacy today invites a look back at a time when reading was more than a pastime. More than a century ago, American writer and minister Gerald Stanley Lee captured reading’s transformative power in The Lost Art of Reading (1904): “The novel which gives itself to one to be breathed and lived… is the one which ‘gets a man somewhere’ most of all.”

Often described as America’s “golden age of reading,” the mid-20th century was a period when print media dominated daily life and literacy was widely cultivated across generations, supported by robust libraries, vibrant print journalism, and school curricula that treated reading as a central pillar of cultural participation.

According to NEA surveys, in the late 1940s, roughly 56–57 percent of adults read novels, short stories, poetry, or plays for pleasure. Daily newspaper readership was high, with about 65 percent of adults subscribing to or regularly reading newspapers, according to historical data from the Pew Research Center, while magazines such as Life, Time, and Reader’s Digest reached tens of millions of households.

Children and adolescents also read frequently outside of school, with 60–70 percent engaging in daily or near-daily reading, sustained by libraries, schools, and family practices, according to the National Literacy Trust. The period also saw the rise of shared reading experiences—fueled by organizations like the Book-of-the-Month Club and the Literary Guild—which broadened access to new titles, shaped national reading tastes, and helped make communal reading a mainstream cultural pastime.

The Data of Decline

By the early 2000s, national surveys were already signaling a decline in leisure reading in the United States. The NEA’s 2007 report “Reading at Risk: To Read or Not to Read: A Question of National Consequence” found that only 46.7 percent of adults read literature for pleasure, down from 54 percent a decade earlier.

Subsequent NEA surveys confirmed that the proportion of adults reading 12 or more books per year continued to fall. Gallup polls also reported a decline in the number of books read per year, from an average of 15.6 in 2016 to 12.6 in 2021. Time-use data from the American Academy of Arts & Sciences also shows that the share of Americans reading more than 20 minutes a day for personal interest dropped from 22.3 percent in 2003 to 14.6 percent in 2023.

Reading habits in the U.S. vary sharply by community type, income, and education. According to Pew (2021) and Library Research Service (2022), adults with higher education and income levels are far more likely to read regularly, while a 2011 Pew survey shows that rural residents lag behind urban and suburban peers, with fewer adults reporting reading for pleasure in the past year. Pew’s 2011 research found that 80 percent of urban and suburban adults read at least one book in the prior year, compared with 71 percent of rural adults, with significantly higher reading rates among college-educated and higher-income Americans than among less-educated and lower-income groups, revealing unequal cultural divides.

A landmark 2025 study published in iScience underscores the cultural shift reflected in declining reading habits. Tracking 236,270 individuals over two decades (2003–2023), the study examined both personal reading and reading with children and found that the share of U.S. adults reading for personal interest on an average day fell from roughly 28 percent in 2004 to 16 percent in 2023—a drop of about 12 percentage points.

“This is not just a small dip—it’s a sustained, steady decline of about 3 percent per year. It’s significant and it’s deeply concerning,” Jill Sonke, PhD, study co-author and director of research initiatives at the University of Florida Center for Arts in Medicine, said in a release about the study.

The research reveals a measurable, persistent, and accelerating trend in specific communities. In many of these households, children also have limited exposure to shared reading at home, further compounding early literacy gaps.

“Reading has always been one of the more accessible ways to support well-being,” said Daisy Fancourt, Ph.D., study co-author and professor of psychology and epidemiology at University College London. “To see this kind of decline is concerning because the research is clear: Reading is a vital health-enhancing behavior for every group within society, with benefits across the life-course.”

Lifelong Reading, Lifelong Benefits

Reading is a powerful tool for brain health, supporting cognitive function and emotional well-being throughout life. A 2009 study by the University of Sussex found that just six minutes of reading a day can reduce stress levels by up to 68 percent—more than listening to music or taking a walk—as well as lowering heart rate, reducing muscle tension, and improving sleep.

A 2020 study in International Psychogeriatrics found that consistent reading habits among older adults are associated with slower cognitive decline—independent of education and other risk factors. What’s more, a 2016 Social Science & Medicine study reported that book readers had roughly a 20 percent lower risk of death than non-readers.

As early as the mid-1940s, librarians and clinicians were documenting the use of reading as a therapeutic tool—a practice that came to be known as “bibliotherapy.” Case histories published in Library Journal, along with reports from psychiatric hospitals and educational settings, document how carefully chosen books could aid emotional healing, foster insight, and support rehabilitation.

Bibliotherapy is now practiced worldwide in public, academic, and hospital settings and is increasingly used by therapists as a mental-health support tool. As a 2025 BBC Future article notes, “Carefully selected books can provide emotional relief and help readers navigate difficult feelings, offering insights that might be hard to access otherwise.” An influential 2016 study published in Frontiers in Psychology found that engaging with literary fiction activates brain networks involved in social cognition, allowing readers to simulate other people’s thoughts and feelings, even when controlling for age, education, and IQ. “When readers engage with literary fiction, they actively simulate the experiences of others, enabling the use of social‑cognitive capacities in a way that non‑fiction simply does not,” the study notes. “If we become a nation of non-critical, superficial, shallow-skimming non-readers, we have no chance to build the base of empathy, critical analysis, and rigorous knowledge that is imperative for our next generation,” Reader, Come Home author Wolf said in an interview with the UCLA School of Education & Information.

The benefits begin early: A 2024 Psychological Medicine study of over 10,000 American children found that those who read early scored higher on cognitive tests and fared better emotionally as they entered adolescence. Yet many kids are missing out: A 2025 HarperCollins UK study reports that only 41 percent of kids ages 0–4 are read to regularly—a drop from 64 percent in 2012. The researchers note that Gen Z parents—many of whom grew up in the digital age—are more likely to see reading as academic rather than enjoyable. Nearly 30 percent say reading is “more a subject to learn than a fun thing to do,” compared with 21 percent of Gen X parents—and kids are following their lead: According to the study, 29 percent of children ages 5–13 now say reading feels like schoolwork, up from 25 percent in 2012.

“It’s very concerning that many children are growing up without a happy reading culture at home,” said Alison David, Consumer Insight Director at Farshore and HarperCollins Children’s Books, in a release about the study. “Children who are read to daily are almost three times as likely to choose to read independently compared to children who are only read to weekly at home.”

Early disparities in reading habits often persist into adulthood: American high school seniors are reading at lower levels than they have in over two decades, according to the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) report, which reveals a continuing long-term decline.

Low-Literacy, High Stakes

The stakes extend far beyond the classroom. Lesley Muldoon, executive director of the National Assessment Governing Board, warns, “These students are taking their next steps in life with fewer skills and less knowledge in core academics than their predecessors a decade ago, and this is happening at a time when rapid advancements in technology and society demand more of future workers and citizens, not less.”

Analysis from the 2023 Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) reveals a “dwindling middle” in skill distribution, with more Americans clustering at the bottom levels of proficiency than in previous assessments. According to the study, the share of adults performing at the lowest literacy level rose from 19 percent in 2017 to 28 percent in 2023, and fewer than half of adults now reach the highest proficiency levels.

Low adult literacy is estimated to cost the U.S. economy $2.2 trillion annually, factoring in lost productivity, higher healthcare spending, and other social costs, according to a 2021 Adult Literacy and Learning Impact Network study, which reports that more than half of American adults read at Level 2 or below, and nearly 30 percent struggle with the most basic texts, limiting job opportunities and career growth.

The Rise of Digital Media

Such widespread literacy challenges don’t exist in a vacuum—they collide with a rapidly changing media environment that makes deep reading even harder to sustain. In today’s “attention economy,” digital platforms feast on Americans’ media appetite, serving a constant menu of bite-sized, algorithm-curated news and “infotainment” via phones, tablets, and streaming feeds. As more Americans turn to gig work and experience growing time scarcity, sustained reading is increasingly squeezed out by the low-effort pull of online streaming—according to Pew Research, roughly 83 percent of U.S. adults turn to online streaming, revealing how both shrinking leisure time and intense competition for attention are driving the decline.

Pew Research shows that 86 percent of Americans now get news digitally, while only 7 percent rely on print newspapers. According to Pew’s Social Media and News fact sheet, about 53–54 percent of U.S. adults report getting news from social platforms at least sometimes. Facebook (38 percent) and YouTube (35 percent) remain the leading news sources, followed by Instagram (20 percent), TikTok (17 percent), and X/Twitter (12 percent). Streaming has also become deeply embedded in American culture, with 83 percent of adults reporting use of streaming services.

Reading is no longer just a solitary pastime—it faces increased competition from online communities, social media, and other digital distractions. The mid-20th-century “middlebrow” culture, where book clubs, newspapers, and mass-market fiction created shared cultural touchstones, has largely faded. As Thomas Jefferson warned, “An informed citizenry is the only true repository of the public will,” and yet being “well-read” no longer carries the social prestige it once did; literacy and engagement with books are less visible markers of cultural participation, reducing the societal incentives to read deeply or widely. This dramatic migration to digital formats is not merely a change in medium—it is transforming the cognitive and social contexts in which information is interpreted. The combination of fast-paced digital formats, viral misinformation, and partisan echo chambers amplifies skepticism, making it harder for audiences to distinguish reliable reporting from opinion or disinformation.

A 2025 Gallup survey reveals that Americans’ confidence in mass media has plunged to a historic low—just 28 percent now say they have “a great deal” or “a fair amount” of trust in newspapers, TV, and radio to report news “fully, accurately and fairly.” The survey notes that when it began polling in the 1970s, trust ranged from 68 percent to 72 percent.

Screen-Inferiority Effect

The move from print to screens represents a fundamental change in how Americans encounter reading content, sharpening concerns about how people, especially students, process what they read—and where they read it.

A growing body of research suggests that reading on screens can undermine comprehension, attention, and deep engagement compared with print. This phenomenon, dubbed the “screen inferiority effect,” appears to stem from three key issues: cognitive overload (digital reading encourages multitasking and scrolling), a lack of spatial landmarks (print’s physical layout helps our brains remember where information is on the page), and the tendency to skim when reading online.

Young readers may be the hardest hit. Research suggests that children who grow up with paper books not only score better on reading assessments but may also achieve more academically—those with access to physical books reportedly complete an average of three more years of education. MRI studies show that these children develop stronger neural connections in brain regions responsible for language and self-control—connections that screen-heavy kids may lack.

Leisure reading on digital platforms has also been linked to lower comprehension among children and young adults, according to a 2023 Scholastica review, and other long-term studies suggest that print reading fosters stronger retention and deeper cognitive processing, as reported by The Guardian.

A 2025 study published in Frontiers of Psychology examined how different modes of reading—paper, digital, audio, and video—affect cognition and mental health of college students, finding that participants who read literary works in paper (or listened in audio formats) showed the greatest improvements, demonstrating better cognitive function and lower levels of anxiety and depression than those in digital, video, or control groups.

“Reading has declined because it’s facing growing competition from other forms of media consumption that may offer students more immediate gratification,” Martin West, professor of education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the deputy director of the Program on Education Policy and Governance at the Harvard Kennedy School, noted in a 2025 “Harvard Thinking” podcast.

“I think we have a lot of evidence to support the extent to which technology can be a distractor when students are engaged in learning processes. And that ability to distract, to compete for attention, could also lead to diminished appetite for persistence in reading on their own,” said West.

The Literacy Divide

The challenge isn’t just attention—it’s the unraveling of support systems that sustain reading in schools, including rising book prices, unequal access, and weakened infrastructure, all of which are eroding opportunities for leisure reading and amplifying the economic pressures behind the decline. According to the Center for American Progress 2024 report “Investing in School Libraries and Librarians to Improve Literacy Outcomes,” more than 50 years of research show that students with access to well‑resourced school libraries with certified librarians consistently perform better academically and score higher on standardized assessments.

However, America’s public schools have quietly but steadily shed thousands of certified school librarians. A national analysis from the School Librarian Investigation—Divergence & Evolution (SLIDE) Project found that librarian positions dropped by about 20 percent between 2009 and 2019, even as many districts increased spending on other staff roles.

The losses were not evenly shared: High-poverty districts, schools serving mostly Black, Hispanic, or multilingual students, and small rural systems were far more likely to lose their certified librarians entirely. Charter schools were hit hardest: Roughly 90 percent reported having no librarians at all. The strain on school libraries reflects a broader crisis in the U.S. public library system, where staffing shortages, budget pressures, and reduced services are also concentrated in high-poverty, high-minority, and rural districts. A study published as an EdWorkingPaper finds that between 2008 and 2019, 766 public library outlets closed, disproportionately affecting rural areas; the closures were associated with declines in nearby students’ reading and math test scores.

Tests Over Texts

Access to books shapes not only what students can read but also how reading is taught. A growing emphasis on standardized testing has increasingly displaced literature, narrowing curricula to measurable skills and focusing on short texts and assessment at the expense of sustained reading or literary exploration. “A critical part of becoming a literate person is to examine and explore a full text. This should be a major part of every student’s education,” writes Peter Greene in “The Atomization of Literature: How Standardized Testing Is Killing Reading Instruction,” published in Forbes.

“Instead of teaching students how to read a whole book, we teach them how to take a standardized test,” Greene argues, adding, “As long as high-stakes testing pushes a quick, superficial solo reaction to a context-free excerpt, schools will deprioritize teaching reading and literacy as a reflective, collaborative, thoughtful deep dive into a complete work. And that will be a loss for students.”

Rose Horowitch, in her 2024 Atlantic article “The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books,” cites a 2024 EducationWeek Research Center survey of about 300 third-to-eighth-grade educators, noting that only 17 percent said they primarily teach whole texts; an additional 49 percent combine whole texts with anthologies and excerpts. Horowitch emphasizes that nearly a quarter of respondents said that books are no longer the center of their curricula. “Whether through atrophy or apathy, a generation of students is reading fewer books,” writes Horowitch. “Students see reading books as akin to listening to vinyl records—something that a small subculture may still enjoy, but that’s mostly a relic of an earlier time.”

Counter-Currents: Signs of Hope

From smartphones to e-readers, new technology is beginning to erode the long-standing resilience of the paper book. About 30 percent of U.S. adults now read books digitally, according to the Pew Research Center. Audiobooks are experiencing even faster adoption: The Audio Publishers Association 2025 Consumer Survey found 51 percent of Americans aged 18 and older—an estimated 134 million people—have listened to an audiobook.

That momentum is matched—and in some ways surpassed—by the popularity of podcasts. Podcasting is booming in the U.S., reaching 210 million Americans and drawing 115 million weekly listeners as of 2025, according to Edison Research. Podcasting now accounts for roughly 11 percent of daily audio consumption, and over 1.1 million English-language podcast episodes have been identified via public RSS feeds.

One bright spot is that independent bookstores are experiencing a resurgence, often supported by local communities and curated events, and subscription book boxes make discovering new titles easier than ever. Social media, particularly TikTok’s “BookTok,” has become a powerful driver of reading among Gen Z, propelling interest in specific genres and bestselling titles. The growth of book‑subscription services suggests a counter-current supporting reading: the global market, valued at about $1.34 billion in 2024, is projected to nearly double by 2033, as more consumers seek curated deliveries to keep reading habits alive

The Path Ahead

To reverse the reading recession in the United States, experts say efforts need to reach across schools, families, and communities. “It will take a comprehensive ecosystem to support our students at every touchpoint,” says Dr. Paige Pullen, chief academic officer and literacy principal at the University of Florida’s Lastinger Center for Learning, in a releaseabout the innovative New Worlds Reading Initiative.

Created by the Florida Legislature in 2021, the program illustrates how multi-level, coordinated approaches can address declining reading rates. Offering modular training for educators from birth through 12th grade, incorporating evidence-based strategies, practical classroom applications, and ongoing mentorship, the initiative aims to support teachers in applying literacy practices in the classroom while promoting collaboration across schools and communities, helping ensure students receive consistent guidance in developing reading skills at each stage of learning.

Across the United States, several states are implementing ambitious literacy initiatives to address persistent reading gaps. Iowa, Arizona, Nebraska, Rhode Island, and Alaska have all received multi-million-dollar federal Comprehensive Literacy State Development (CLSD) grants to support evidence-based reading instruction, high-dose tutoring, and professional development for educators, with a focus on children in high-need communities. A range of literacy nonprofits and school programs are also stepping in to bolster reading skills and access to books, particularly for children in under-resourced communities.

The NEA offers a range of solutions to promote early reading at home—from in-clinic programs to digital tools and grassroots book-sharing initiatives. Nonprofits Reading Is Fundamental (RIF) and the Children’s Literacy Initiative are expanding access to books, supporting teachers, and strengthening reading instruction where schools need it most.

Raising a Reader partners with schools, community centers, and libraries to provide curated, multicultural book collections and training for parents. Reach Out and Read integrates literacy into pediatric care, giving books to young children during well-child visits and coaching caregivers on reading aloud together.

Worldreader—a global nonprofit that promotes family reading through its free digital app, BookSmart—is helping parents read to their children daily, even in low-resource settings.

Grants, policy incentives, and strategic partnerships are also critical to ensuring these efforts are sustainable and equitable. A policy brief from the Center for American Progress, “Investing in School Libraries and Librarians to Improve Literacy Outcomes,” argues that investing in certified school librarians, up-to-date collections, and teacher collaboration is a powerful lever to boost student literacy and long-term reading engagement.

Emerging technologies, such as augmented reality (AR technology) storybooks (Metabook) and interactive voice-assisted reading (TaleMate), combine engagement with learning, demonstrating how digital and print strategies can work together to foster reading habits, improve literacy outcomes, and transform libraries into immersive learning hubs.

Programs like Open eBooks—a collaboration among major publishers, libraries, and nonprofits—provide free access to thousands of eBooks for children in under-resourced communities. Penguin Random House’s Living Stories app merges read-aloud sessions with interactive lights and sounds to engage young readers. Library software providers like BiblioCommons integrate e-books into public library catalogs. At the same time, platforms such as Reading Plus and collaborations like Reading Partners + AT&T deliver personalized, digital literacy instruction to students at school and home.

Reversing America’s reading decline requires more than urging kids to pick up a book—it demands rebuilding a culture that champions literacy at every stage of life. This means addressing funding and staffing crises in school and public libraries, rethinking teaching practices that undervalue deep reading, and supporting parents in fostering early literacy. It also calls on policymakers, educators, and communities to invest in the long-term infrastructure that literacy requires.

The stakes are high: without intervention, the next generation risks inheriting a world of perpetual scrolling, fragmented attention, and shallow engagement with ideas. But with coordinated action, we can envision a future where books, both print and digital, reclaim their role as catalysts for curiosity, empathy, and civic understanding. Reading can once again be a shared cultural experience, a personal joy, and a cornerstone of an informed, connected society.

Kate Petty is an educator, writer, and environmental activist. She has worked with the New York Nature Conservancy and various United Nations initiatives, including UNICEF, the World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations, and the Universal Versatile Society to promote education, social justice, and solution-oriented projects for a healthier planet. She is a contributor to the Observatory.

This article was produced for the Observatory by the Independent Media Institute. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)