‘If you discount their stubbornness’

Scene from Hogback Mountain, Wilmington, Vt.

“Look. And smell. Breathe deeply. Feel the air; touch it now and sense its purity, its vigor, its super-constant juvenation (that supposedly has given Vermonters their long life — if you discount their stubborness.’’

— Evan Hill, in The Connecticut River (1972)

xxx

“Vermont is a land filled with milks and maple syrup, and overrun with New Yorkers.’’

— John L. Garrison, in 1946

Painting shaping photography

Overpainted full plate tintype, circa 1860’s-’70’s, in the show “Photography and the Painted Image,’’ at the Lyman Allyn Art Museum, New London, Conn., Jan. 17-April 12.

The museum explains:

“This exhibition explores the intersection between photography and painting, highlighting the ways in which the two mediums have overlapped and complemented each other.

The first section showcases the painted backdrop, a hallmark of 19th- and early 20th-Century portrait studios, where elaborate hand-painted backgrounds framed sitters within idealized worlds.

“The second section turns to the painted foreground, focusing on carnival and arcade photographs in which participants posed within humorous or fantastical cutouts that transformed their identities through caricatures and other painted figures.

“The final section explores the painted photograph itself – images enhanced, tinted, or entirely transformed by the application of pigment, from subtle hand-coloring to bold overpainting.

“Together, these works reveal how painting not only shaped the settings and surfaces of photography but also extended its capacity for imagination, spectacle, and self-representation, offering new ways of seeing and being seen.’’

Llewellyn King: A reminder of kings and emperors to rise at the White House, to burden the taxpayers for decades

The East Wing of the White House being demolished on Oct. 21, 2025. A huge ballroom paid for by Trump campaign donors and other rich people will replace it. In return for? Thereafter, themass of taxpayers will cover the maintenance costs.

—Photo by Sizzlipedia

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

President Donald Trump is building what will become one of the greatest snow-colored pachyderms in the history of the United States.

Some of the nation's biggest tycoons are going to pay to build this ballroom, which will look like the box that the rest of the White House came in — a statement often made about the Kennedy Center looking like the container that the adjacent Watergate complex came in.

Those favor-seeking tycoons won't be around to maintain the building as it stands mostly empty through the decades. Buildings that stand empty deteriorate rapidly. This piece of megalomania, expressed in stone, concrete and gold leaf, will be a burden to taxpayers.

Its ostensible purpose is for state dinners, where heads of state we as a nation want to flatter are dined. They should be called state ingratiation events.

When the president of the United States gives you a state dinner, you are exalted, whether it is haute cuisine in a gilded neoclassical building that looks like a 19th-Century railroad station or in a tent. The office of the president doesn't need gold leaf and vaulted ceilings to embellish it.

"Location, location, location," say the real-estate agents, and there's the rub. The White House is, by design, inaccessible.

I can say this with authority because for years I had a so-called White House hard pass and could gain entry quite easily. Even with it, my personal belongings and I had to pass through scanners at the visitor gates.

If you don't have a hard pass, you will have a hard time. You need an escort, and that must be arranged. Things lighten up a bit for events such as the Christmas parties. If you want to be there in time to have your picture taken shaking hands with the president, get there extra early.

The White House gates are a nightmare, and sometimes precleared names are lost mysteriously in the computer system. This happened to a reporter who worked for me who was invited to a press picnic held on the South Lawn during the Clinton administration. The poor fellow had to stand outside the gate like an untouchable while the rest of us got through.

Eventually, he got in. President Bill Clinton — who had an extraordinary ability to find a discomforted person in any situation and make them feel good — put his arm around the reporter in no time. When you have had difficulty getting into the White House, you mostly just feel rejected. The Secret Service makes a person waiting to be cleared for entry at the gates feel inferior or implies that they are up to no good.

My wife, Linda Gasparello, a fully accredited White House correspondent at the time, used her influence to get the crooner Vic Damone, who had an appointment, past the implacably suspicious gatekeepers. He was nearly in tears of frustration from the way he was treated.

The envisioned shimmering excess at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue won't lend itself to being used for charity events or non-White House galas. It will be just too difficult to get in.

Washington isn't short on big, fancy spaces. I believe that the biggest (besides armories and hangars) is the ballroom of the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. That room can seat over 2,700 and hold 4,600 for non-dinner events.

The Trump Ballroom would accommodate 1,000, we are told, presumably seated. So, it is too small for one kind of event and possibly too big for other events that might take place at the White House, if the attendees can get through the security barriers.

Washington isn't London or Paris. It isn't overstocked with grandiose ceremonial structures built by kings and emperors for their own aggrandizement. Instead, it has fun spaces that are pressed into service for formal affairs, such as the Spy Museum, the National Building Museum or the Air and Space Museum, in keeping with a nation that prizes its citizens over its leaders.

It seems to me that it is wholly appropriate for the United States to show national humbleness, as befits a country that threw off a king and his grandeur 250 years ago.

I have always thought that the tents put up for state dinners at the White House had a particularly American charm — a modest reproach to the world of dictators and fame-seekers, an unsaid rebuke to ostentation.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant.

As it shrinks

“Union Pacific's Rock-filled Causeway” (photo of Great Salt Lake, Utah) by Sallie Dean Shatz, from the “Learning Humility from a Dying Lake’’series, in the show “Human Impact: Contemporary Art and Our Environment,’’ at Burlington (Vt.) City Arts, March 13-June 20.

She explains:

“The causeway stretches 20 miles across the Great Salt Lake dissecting it (you can see it in the satellite images to the left.) The causeway was built with two bridges that water could flow through. It has been used to cut off the access of water between the north and south arm, sacrificing the north arm to save the ecosystem of the south arm.

“The south arm has more fresh water flowing into it from the mountains than the north arm. The salinity of the north arm is currently 34%. The current salinity for the south arm is 11.2%. For reference oceans are 3% salinity. The color of the north arm changes by season with the growth of archaea as seen in some of the other images in this exhibit. Note the archaea (pink) seeping into the south arm along the causeway.’’

Chris Powell: Of teachers’ salaries, per-student parenting and generational poverty in Connecticut

Fancy Staples High School, in rich Westport, Conn.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Will Connecticut ever realize that two of what it professes to be its highest ideals of public policy, local control and equality of opportunity, are contradictions?

State government was reminded of this again the other day by another report

Connecticut's teacher pension system perpetuates inequity in student tes...

from the Equable Institute, a nonprofit organization that seeks to improve government employee pensions. Connecticut's state teacher- retirement system, the institute notes, does much better by teachers in wealthy municipalities than those in poor ones, because teacher pensions are calculated from their salaries. Wealthy municipalities pay more so their teachers get bigger pensions.

Indeed, Equable says state government pays twice as much for the pensions of teachers in some wealthy municipalities than it pays for the pensions of teachers in some poor ones.

Additionally, because of the higher salaries they pay, wealthy municipalities suffer less turnover in their teaching staffs and retain better teachers longer than poor municipalities do.

Equable says the disparity in pension contributions is responsible for some of the disparity in student performance between wealthy and poor municipalities. That stands to reason, but pension disparities surely matter far less to educational results than the disparities in the household wealth of students and the amount of parenting they get.

As usual, liberals and teachers unions like to attribute all the deficiencies of public education to inadequate spending, even though Connecticut has been raising education spending steadily for almost 50 years, improving teacher salaries and pensions without improving student performance.

Per-pupil parenting has always been the main determinant of student performance, but politics prohibits addressing the parenting problem. No elected official or candidate dares to note the strong correlation between single-parent households and child neglect and abuse, student educational failure, poor physical and mental health, and general misbehavior. Acknowledging that correlation would impugn the entire welfare system and the perverse incentives it gives the poor, and it would show where so much social disintegration is coming from.

But everyone admires teachers as individuals, so finding public money for satisfying them and their unions is easy and doesn't cause the political problems that examining the causes of poverty would.

It's no wonder that teachers prefer to teach well-parented, well-behaved, attentive, and curious kids rather than poorly parented, ill-behaved, and indifferent or demoralized kids. It's no wonder that teachers in impoverished cities, like police officers there, can get worn down quickly and seek to pursue their careers in municipalities with less poverty and dysfunction. This is just another aspect of the flight to the suburbs, which has been caused by government's failure to solve poverty in the cities.

Maybe state law should arrange for all teachers to be paid directly by state government according to the same salary schedule so their pensions would be equalized. No adjustments for union contracts or individual merit could be permitted, since they would generate inequality.

Such an egalitarian system likely would reduce salaries and pensions in wealthy and middle-class municipalities and increase them in poor ones. But of course teacher unions would never give up bargaining power over wages and benefits, not in the pursuit of equality or anything else.

Or maybe teachers in the poorest municipalities should be paid at least $100,000 per year more than teachers in the highest-paying municipalities. They might not all be good teachers but most might deserve more money just for having to deal with so many indifferent and misbehaving students.

While that might be fairer to those teachers, who are part of the constituency the Equable Institute is trying to help, Connecticut's long experience would still be that school spending is almost irrelevant to educational performance, and the presumption of increasing teacher salaries and pensions would still be that the job satisfaction of teachers is more important than education itself and ending generational poverty.

But even the long failure to end generational poverty isn't the biggest problem here. The biggest problem here is simply Connecticut's failure to care much about it. As a political matter, paying off the teachers is the most we can do.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Display it and let it degrade

“Gathering My Thoughts” (Ohio-grown willow), by Laura Ellen Bacon, at the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Mass., through Oct. 12, 2026.

— Photo by Derek Hansen

The museum says:

Ms. Bacon “weaves her sculptures from slender strands of willow. Gradually, twist by twist, she builds an enormous form with a complex interior structure. The technique is entirely original to her, but has affinities with such rural English crafts as fences, baskets, and thatching, as well as the nests and burrows of birds and other animals. Bacon has conceived her work for the Clark as a record of its own making: each of the overlapping volumes represents one day of her skilled labor. Together, they accumulate into an organic shape, like an outgrowth of the woodland floor. She enjoys the fact that the sculpture may become a habitat for insects and other creatures. Because it is made entirely from natural materials, it will be disassembled and allowed to degrade into the forest floor.’’

Cullen Paradis: Boston/Cambridge ranked as nation’s third biggest innovation hub

MIT's central and east campus from above the Harvard Bridge. Left of center is the Great Dome over Killian Court, with the Stata Center behind.

— Photo by Nick Allen

(Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s editor/publisher, is The Boston Guardian chairman.)

While residents may complain about poorly timed traffic lights and power outages, Boston and Cambridge have been ranked the third largest innovation engine in America and the ninth worldwide.

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPOP), a subsidiary of the United Nations that tracks, protects and distributes intellectual property, has released new data on which cities and regions around the globe are innovation hotspots in 2025.

Boston placed quite well nationally, ranking behind only San Francisco and New York City.

“Innovation clusters, whether innovation-driven cities or regions, form the beating heart of national innovation systems,” the report said.

“These hubs unite top universities, researchers, inventors, venture capitalists and research and development (R&D) firms in driving forward breakthrough ideas. From Bengaluru to Berlin, Boston to São Paulo, Shenzhen or Seoul, global cities blend research, start-ups and R&D firms to power innovation.”

WIPO’s global innovation index (GII) measures a combination of investment in innovation, technological progress and adoption of new technologies, and socioeconomic impacts. Boston actually does even better on rankings that take size into account, scoring 3rd globally behind only San Francisco and Cambridge, UK. WIPO gave special notice to San Francisco and Boston as the only cities to place top ten in both overall innovation and innovation density.

Those placements have real numbers behind them, with one of every hundred publications filed worldwide coming from Boston according to WIPO metrics. One of every sixty-six international patent treaties comes from Boston, and one of every fifty venture capital dollars spent globally is invested right here.

A large part of that is Boston’s education system.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) got second place in the Times Higher Education 2026 rankings with a perfect 100 points for industry connections and innovation. WIPO also noted that the Quacquarelli Symonds World University 2026 rankings gave MIT first place globally with a perfect 100.

Harvard Medical School got its own shoutout from WIPO as the region’s top scientific organization.

Other private enterprises played their own role, with Boston Scientific coming third in WIPO’s global ranking of medical device companies.

Boston’s rankings this year are a shift from 2024, better in some areas but slipping slightly back in others. While not all of the metrics between years are the same, Boston’s placement on the overall ranking slipped from 8th to 9th in 2025. Ranked with density taken into account, however, saw Boston jump from 5th place to 3rd. This could suggest that while Boston is ramping up innovation investment it’s not enough to fully compensate for the city’s size.

“The GII uses a bottom-up, data-driven methodology that disregards administrative or political borders and instead pinpoints those geographical areas where there is a high density of inventors and scientific authors,” said the 2025 report.

The city’s placements in 2024 were mostly the same for 2023 and 2022 as well, suggesting that this is a recent change rather than the continuation of an ongoing trend.The mayor’s office, Harvard Medical School and the MIT did not respond to a request for comment on this article by press time.

Top 10 innovation clusters

1. Shenzhen-Hong Kong-Guangzhou

2. Tokyo-Yokohama

3. San Jose-San Francisco

4. Beijing

5. Seoul

6. Shanghai-Suzhou

7. New York

8. London

9. Boston-Cambridge

10. Los Angeles

Cullen Paradis is a Boston Guardian contributor.

Criminally cute?

From the “Whiskers and Whimsy: Animals in Currier & Ives Prints’’ show at the Springfield (Mass.) Museums through Jan. 4

The museum explains:

“Currier & Ives, the New York City-based printmaking firm operating from 1835 to 1907, played an outsized role in shaping American visual culture with their scenes from military history and landscapes. Additionally, Nathaniel Currier (American, 1813–1888) and James Merritt Ives (American, 1824–1895) found widespread appeal for their ‘sentimental prints’ that featured puppies, kittens, and birds—often in comical situations!’’

Celine Gounder: The quiet collapse of America’s reproductive-health system

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News, except for inage above.

In late October, Maine Family Planning announced three rural clinics in northern Maine would close by month’s end. These primary-care and reproductive health clinics served about 800 patients, many uninsured or on Medicaid.

“People don’t realize how much these clinics hold together the local health system until they’re gone,” said George Hill, the group’s president and CEO. “For thousands of patients, that was their doctor, their lab, and their lifeline.”

Maine Family Planning’s closures are among the first visible signs of what health leaders call the biggest setback to reproductive care in half a century. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Population Affairs, which administers the Title X family planning program, has been effectively shut down. At the same time, Medicaid cuts, the potential lapse of Affordable Care Act subsidies, as well as cuts across programs in the Health Resources and Services Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are eroding the broader safety net.

“When you cut OPA, HRSA, and Medicaid together, you’re removing every backup we have,” said Clare Coleman, president of the National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association. “It’s like taking EMTs off the road while closing the emergency rooms.”

Asked about the cutbacks, HHS press secretary Emily G. Hilliard said, “HHS will continue to carry out all of OPA’s statutory functions.”

How the Safety Net Frays

For more than 50 years, Title X has underwritten a national network of clinics, now numbering over 4,000, that provide contraception, pregnancy testing, testing and treatment for sexually transmitted infections, cancer screening, and other primary and preventive care to nearly 3 million low-income or uninsured patients annually. OPA managed nearly $400 million in grants, issued clinical guidance, and ensured compliance.

In mid-October, OPA’s operations went dark amid federal layoffs that also affected hundreds of CDC staffers. “Under the Biden administration, HHS became a bloated bureaucracy — expanding its budget by 38% and its workforce by 17%,” a spokesperson for the department said at the time, adding, “HHS continues to eliminate wasteful and duplicative entities, including those inconsistent with the Trump administration’s Make America Healthy Again agenda.”

According to Jessica Marcella, who led OPA under the Biden administration, the office was previously staffed by 40 to 50 people. Now, she says, only one U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps officer remains.

“The structure to run the nation’s family planning program disappeared overnight,” said Liz Romer, OPA’s former chief clinical adviser.

“This isn’t just about government jobs,” Coleman said. “It’s a patient-care crisis. Every safety-net program that touches reproductive health is being weakened.”

Linking Health, Autonomy, and Opportunity

Created in 1970 under President Richard Nixon and rooted in President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, Title X was designed as a cornerstone of preventive public health, not a partisan cause. Nixon called family planning assistance key to a “national commitment to provide a healthful and stimulating environment for all children,” and Congress agreed overwhelmingly across party lines.

The Biden administration shut off federal family- planning grants to Tennessee and Oklahoma after the states directed clinics not to provide abortion counseling. The Trump administration restored the money, claiming two lawsuits were settled. They weren’t.

Sara Rosenbaum, a professor of health law at George Washington University, said the program reflected a pivotal shift in how policymakers understood health itself.

“By the late 1960s, there was a deep appreciation that the ability to time and space pregnancies was absolutely essential to women’s and children’s health,” she said. “Title X represented the idea that reproductive care wasn’t a privilege or a moral issue. It was basic health care.”

UCLA economist Martha Bailey later found that children born after the first federally funded family-planning programs were 7% less likely to live in poverty, and had household incomes 3% higher, than those born before. Research by Bailey just published by the National Bureau of Economic Research showed that when low-income women can access free birth control, unintended pregnancies drop by 16% and abortions drop by 12% within two years.

Those findings underscore what Rosenbaum calls “one of the great public health achievements of the 20th Century — a program that linked economic opportunity to health and autonomy.”

That bipartisan foundation and evidence-based mission, Rosenbaum said, make today’s unraveling especially striking.

“What was once common sense, that access to family planning is essential to a functioning health system, has become politically fragile,” she noted. “Title X was built for continuity, but it’s being undone by neglect.”

Hidden Health Risks Behind Unplanned Pregnancies

Family planning is central to maternal and infant health because it gives women the time to optimize such medical conditions as high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart disease before pregnancy, and allows them to safely space out their births.

“Pregnancy is the ultimate stress test,” said Andra James, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist who advised the CDC on its contraceptive guidelines.

“It increases the heart’s workload by up to 50%. For people with heart disease, diabetes, or hypertension, that stress can be dangerous.”

Brianna Henderson, a Texas mother, learned this firsthand. Weeks after delivery, she developed peripartum cardiomyopathy, a form of heart failure that can occur during or after pregnancy. She survived. Her sister, who had the same undiagnosed condition, died three months after giving birth to her second child. Those kids are now 12 and 16, and they’re growing up without a mom. Their dad and his mother look after the kids now.

“Contraception has been a lifesaving option for me,” Henderson said.

James and other specialists warn that without CDC-informed guidance on contraceptive safety for complex conditions, clinicians and patients are left without clear, current standards.

What History and Data Predict Happens Next

Title X clinics provide millions of STI tests each year and are often the only cancer screening sites for uninsured women. Cuts to Medicaid and ACA subsidies will make it even harder for people to afford preventive visits.

“If these clinics close, we’ll see more infections, more unplanned pregnancies, and more maternal deaths, especially among Black, Indigenous, and rural communities,” said Whitney Rice, an expert on reproductive health at Emory University.

And the geographic gaps are large already. Power to Decide, a nonprofit reproductive rights group, counts more than 19 million women living in “contraceptive deserts,” where there’s no reasonable access to publicly supported birth control.

“These are places where the nearest clinic might be 60 or 100 miles away,” said Power to Decide interim co-CEO Rachel Fey. “For many families, that distance might as well be impossible.”

High Price of Short-Term Savings

Each pregnancy averted through Title X saves about $15,000 in public spending on medical and social services, according to an analysis by Power to Decide. And an analysis by the Guttmacher Institute shows that every $1 invested in publicly funded family-planning programs saves roughly $7 in Medicaid costs.

Cutting federal funding for reproductive health services “isn’t saving money. It’s wasting it,” said Brittni Frederiksen, a KFF health economist and former OPA scientist. “We’ll spend far more fixing the problems these cuts create.” KFF is a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

Supporters of cuts argue federal spending must be reduced and states should set their own priorities.

Strain on the Ground

Some clinics that provide abortions are closing, even in states where voters have passed some of the nation’s broadest abortion protections. It’s happening in such places as New York, Illinois, and Michigan, as reproductive health-care faces new financial pressures.

Affirm CEO Bré Thomas said the state could lose $6.1 million in Title X funding if federal appropriations expire after March 31. It’s a cut that would reduce access to care across the network.

“That’s $6.1 million for Arizona,” she said. “That means over 33,000 patients in our state could lose access to services.”

Thomas noted that two consecutive funding reductions, combined with 11 years of flat federal support and rising health care costs, have already strained operations. Without new funding, she warned, clinics may be forced to limit contraceptive options to cheaper methods, reduce preventive care, and lay off staff, especially in rural communities. “We’re talking about impacts to people’s jobs and their ability to access the care they need,” she said.

Megan Kavanaugh, a scientist at the Guttmacher Institute, underscored those limits.

“Federally Qualified Health Centers do not have the capacity to absorb the number of patients who will lose care,” she said, referring to federally funded community-based clinics for underserved populations. “Some people may find another clinic, but a large share simply won’t, and we’ll see that reflected in higher rates of unintended pregnancy, untreated infections, and later-stage disease.”

Hospitals are beginning to absorb the spillover.

“The safety net is shrinking, and hospitals can’t absorb everyone,” said Sonya Borrero, a reproductive-health expert at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and a former chief medical and scientific adviser at OPA. “Wait times will get longer, and preventable problems will rise.”

Funding Frozen, Oversight Halted

With OPA offline, Title X dollars already awarded can be spent, but no new funds are moving.

“Most programs can hang on for a few months,” Romer said. “By spring, many won’t have enough money to stay open.”

The halt also suspends compliance reviews and technical assistance tied to CDC-aligned guidelines.

Marcella, the former OPA leader, warned of a “backdoor dismantling.”

“If there aren’t people to administer the grants, then the administration can later argue the program isn’t working and redirect the funds elsewhere,” she said. “This is a functional elimination, done quietly.”

Kavanaugh called the moment “one more step toward dismantling the public health infrastructure that has supported people’s reproductive health for decades.”

Without staff to move money and guidance, she said, “that’s how a system collapses.”

What Can Still Be Done

According to the National Association of Community Health Centers, Federally Qualified Health Centers can still use HRSA money that was already approved, even during the government shutdown. But no new funding is being released, similar to the freeze on Title X funds. At the same time, HRSA has stopped first-quarter payments for its Title V Maternal and Child Health program, which limits how states can provide preventive care and services for children and young people with special health needs.

Some states — California, New Mexico, Washington — are plugging holes with state dollars, and health systems are expanding telehealth, but most jurisdictions cannot replace federal support at scale.

“Private donors can’t replace the federal government,” said Hill, of Maine Family Planning. “You can’t crowdfund your way to a working health system.”

Congress could restore Title X and rebuild OPA’s staffing, but without administrators in place, money can’t reach clinics quickly. States have a short window to bridge care by stabilizing Medicaid coverage, shoring up community health centers, and protecting contraceptive access.

“This isn’t a political debate,” Romer said. “It’s women showing up for care and finding the doors locked.”

Céline Gounder is a reporter f0r Kaiser Family Foundation Health News( cgounder@kff.org)

Lunacy in the Litchfield Hills?

From “What Lurks on Channel X,’’ by Rob Zombie, at the Morrison Gallery, Kent, Conn., through Nov. 16.

Justin Reich: History warns us to beware of AI hype for schools

AI-generated draft article getting nominated for speedy deletion under G15 criteria.

From The Conversation, except for image above

Justin Reich is a professor of Digital Media at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

He has received funding from Google, Microsoft, Apple, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Chan/Zuckerberg Initiative, the Hewlett Foundation, education publishers, and other organizations involved in technology and schools.

CAMBRIDGE, Mass.

American technologists have been telling educators to rapidly adopt their new inventions for over a century. In 1922, Thomas Edison declared that in the near future, all school textbooks would be replaced by film strips, because text was 2% efficient, but film was 100% efficient. Those bogus statistics are a good reminder that people can be brilliant technologists, while also being inept education reformers.

I think of Edison whenever I hear technologists insisting that educators have to adopt artificial intelligence as rapidly as possible to get ahead of the transformation that’s about to wash over schools and society.

At MIT, I study the history and future of education technology, and I have never encountered an example of a school system – a country, state or municipality – that rapidly adopted a new digital technology and saw durable benefits for their students. The first districts to encourage students to bring mobile phones to class did not better prepare youth for the future than schools that took a more cautious approach. There is no evidence that the first countries to connect their classrooms to the Internet stand apart in economic growth, educational attainment or citizen well-being.

New education technologies are only as powerful as the communities that guide their use. Opening a new browser tab is easy; creating the conditions for good learning is hard.

It takes years for educators to develop new practices and norms, for students to adopt new routines, and for families to identify new support mechanisms in order for a novel invention to reliably improve learning. But as AI spreads through schools, both historical analysis and new research conducted with K-12 teachers and students offer some guidance on navigating uncertainties and minimizing harm.

Wrong and overconfident before

I started teaching high-school history students how to search the web in 2003. At the time, experts in library and information science developed a pedagogy for Web evaluation that encouraged students to closely read websites looking for markers of credibility: citations, proper formatting, and an “about” page.

We gave students checklists such as the CRAAP test – currency, reliability, authority, accuracy and purpose – to guide their evaluation. We taught students to avoid Wikipedia and to trust websites with .org or .edu domains over .com domains. It all seemed reasonable and evidence-informed at the time.

The first peer-reviewed article demonstrating effective methods for teaching students how to search the web was published in 2019. It showed that novices who used these commonly taught techniques performed miserably in tests evaluating their ability to sort truth from fiction on the web. It also showed that experts in online information evaluation used a completely different approach: quickly leaving a page to see how other sources characterize it. That method, now called lateral reading, resulted in faster, more accurate searching. The work was a gut punch for an old teacher like me. We’d spent nearly two decades teaching millions of students demonstrably ineffective ways of searching.

Today, there is a cottage industry of consultants, keynoters and “thought leaders” traveling the country purporting to train educators on how to use AI in schools. National and international organizations publish AI literacy frameworks claiming to know what skills students need for their future. Technologists invent apps that encourage teachers and students to use generative AI as tutors, as lesson planners, as writing editors, or as conversation partners. These approaches have about as much evidential support today as the CRAAP test did when it was invented.

There is a better approach than making overconfident guesses: rigorously testing new practices and strategies and only widely advocating for the ones that have robust evidence of effectiveness. As with web literacy, that evidence will take a decade or more to emerge.

But there’s a difference this time. AI is what I have called an “arrival technology.” AI is not invited into schools through a process of adoption, like buying a desktop computer or smartboard – it crashes the party and then starts rearranging the furniture. That means that schools have to do something. Teachers feel this urgently. Yet they also need support: Over the past two years, my team has interviewed nearly 100 educators from across the U.S., and one widespread refrain is “don’t make us go it alone.”

3 strategies for prudent path

While waiting for better answers from the education science community, which will take years, teachers will have to be scientists themselves. I recommend three guideposts for moving forward with AI under conditions of uncertainty: humility, experimentation and assessment.

First, regularly remind students and teachers that anything schools try – literacy frameworks, teaching practices, new assessments – is a best guess. In four years, students might hear that what they were first taught about using AI has since proved to be quite wrong. We all need to be ready to revise our thinking.

Second, schools need to examine their students and curriculum, and decide what kinds of experiments they’d like to conduct with AI. Some parts of your curriculum might invite playfulness and bold new efforts, while others deserve more caution.

In our podcast “The Homework Machine,” we interviewed Eric Timmons, a teacher in Santa Ana, Calif., who teaches elective filmmaking courses. His students’ final assessments are complex movies that require multiple technical and artistic skills to produce. An AI enthusiast, Timmons uses AI to develop his curriculum, and he encourages students to use AI tools to solve filmmaking problems, from scripting to technical design. He’s not worried about AI doing everything for students: As he says, “My students love to make movies. … So why would they replace that with AI?”

It’s among the best, most thoughtful examples of an “all in” approach that I’ve encountered. I also can’t imagine recommending a similar approach for a course like ninth grade English, where the pivotal introduction to secondary school writing probably should be treated with more cautious approaches.

Third, when teachers do launch new experiments, they should recognize that local assessment will happen much faster than rigorous science. Every time schools launch a new AI policy or teaching practice, educators should collect a pile of related student work that was developed before AI was used during teaching. If you let students use AI tools for formative feedback on science labs, grab a pile of circa-2022 lab reports. Then, collect the new lab reports. Review whether the post-AI lab reports show an improvement on the outcomes you care about, and revise practices accordingly.

Between local educators and the international community of education scientists, people will learn a lot by 2035 about AI in schools. We might find that AI is like the web, a place with some risks but ultimately so full of important, useful resources that we continue to invite it into schools.

Or we might find that AI is like cellphones, and the negative effects on well-being and learning ultimately outweigh the potential gains, and thus are best treated with more aggressive restrictions.

Everyone in education feels an urgency to resolve the uncertainty around generative AI. But we don’t need a race to generate answers first – we need a race to be right.

‘Just the questions’

“Sunk” (acrylic on canvas), by Claudia Doherty, in her show “Fragments of Her,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Nov. 6-30.

She says:

“What’s on my mind when I paint and when I think about painting is a woman alone. Did she slip away from him or maybe run? Is she relishing solitude or sunken in loneliness? Would she startle if approached? Does she want to crash the waves, trudge through the bog, lie down in the reedy marsh? Is she gutted by a loss, sick with want, motherless, black and blue? I want to see all of this in my paintings, not the answers though, just the questions.”

Small-town energy

Consider Hatch House (built in 1748 but obviously much changed since then), in Falmouth, Mass.

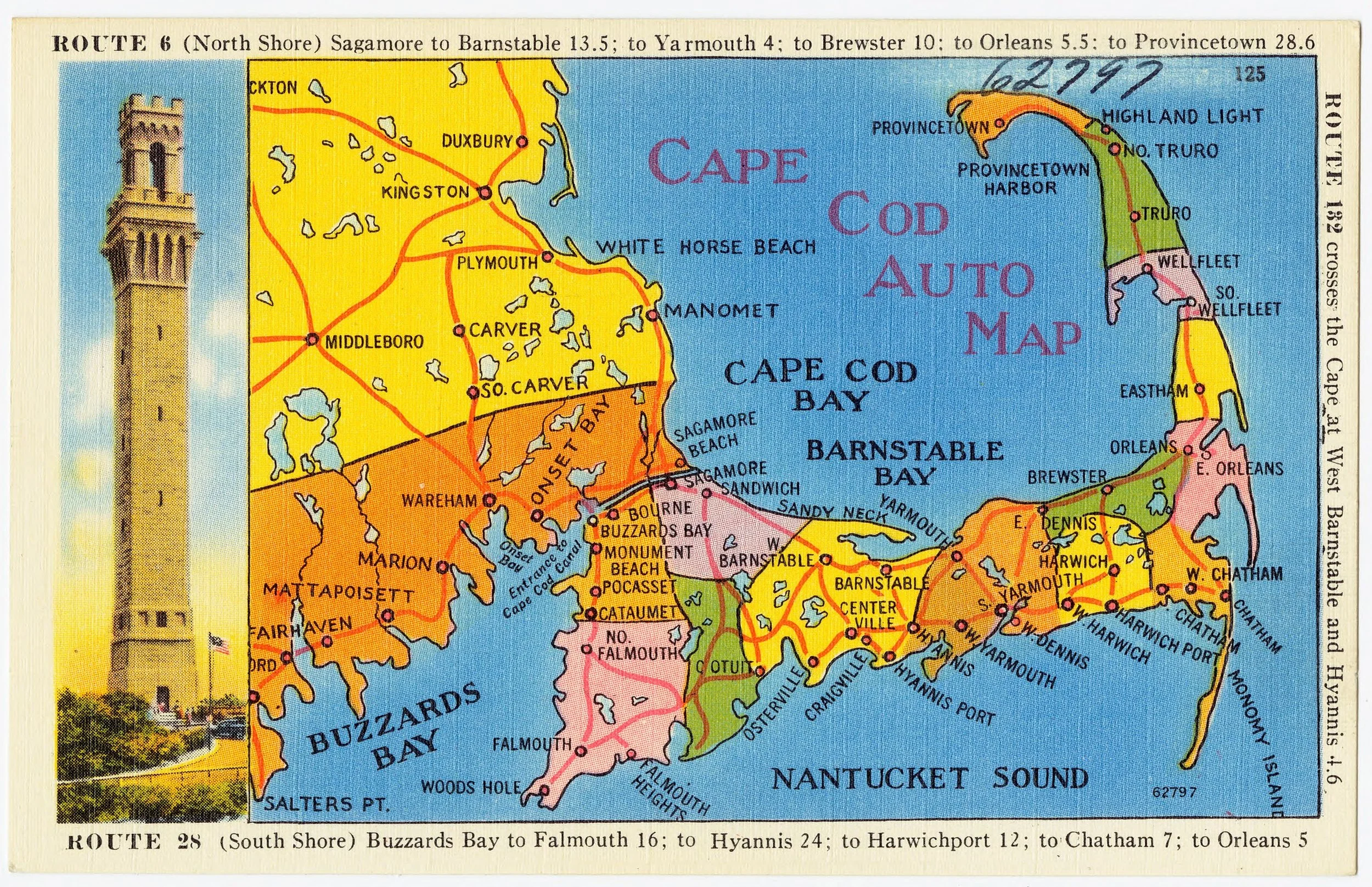

Cape Cod Auto Map, 1930s–40s postcard by Tichnor Bros. of Boston.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I made a recent road trip was to Falmouth, Mass., on the Cape, where I did a little more historical research, mostly about the 19th Century in that town, where many of my ancestors lived. I was struck again by the energy of town leaders, then, in business and civic life. They’d start up a wide range of businesses, from salt collection, to guano processing (for fertilizers), to boat building, to raising sheep for wool, a major sector in New England at the time as textile mills popped up. When one business didn’t pan out they’d go on to the next at a good clip. They were remarkably handy at fixing things, both business plans and equipment. And they did this at a time when transportation was much more difficult than it is now.

Consider that members of the local Butler family who owned the town’s monopolistic town general store, found it easier to ship by boat from New York City some stuff to provision the store than to get it from the much closer Boston area, which often required, before the trains came in, transporting stuff via the sometimes perilous route around Cape Cod in pre-canal days.

While being energetic small-town capitalists, many Falmouth folks were notably civic-minded, of course sometimes out of enlightened self-interest. There seemed to be no dearth of men (in those pre-women’s suffrage days) willing to run for selectman, state representative or other political posts and to promote the construction of schools and other public facilities, as well as churches. And they’d get into heated issues such as by signing petitions to abolish slavery and holding public meetings on that and other matters.

Still, mixed with all this energy, as I can tell from their letters, were fatalism and melancholy, which they seem to have passed on to their descendants.

It was a very different world, of course, but there are some lessons to be learned about building successful communities from Falmouth.

I was struck by how busy downtown Falmouth seemed last week, even though the prime summer people and tourist season ended weeks ago. Half a century ago, it would have been much quieter at this time of year. Maybe that autumns are getting warmer has something to do with it.

And, oh dear!

The Trump regime, whose greatest enthusiasm seems to be to stick it to its real or perceived adversaries, has paused $11 billion in funding for infrastructure projects in some Democratic Party-led cities, including Boston, and put into some doubt the $600 million that the Feds had pledged to help pay to replace the two decaying highway bridges over the Cape Cod Canal, which were built the ‘30’s.

Meanwhile, $172 million in taxpayer money will go to buy two Gulfstream jets for the use of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and her top assistants.

Ms. Noem, as does her boss, loves to flaunt luxury. Some may recall her $50,000 gold Rolex wristwatch; the origin of the money to buy it remains something of a mystery.

Anyway, the public be damned! Some $300 million is being spent to illegally demolish the East Wing of the White House and rebuild it for a huge ballroom where the Orange Oligarch can hold court. But don’t worry, the money is coming from private donors. You can bet that most of them seek special access to the king.

New England’s huge financial-services sector

Boston Financial District

Industry giant Fidelity Investments’ headquarters, at 245 Summer St., Boston.

Read The New England Council’s report on the region’s financial-services industry here.

Llewellyn King: Our dichotomous America

One year after the 2016 election that delivered Donald Trump his first term, American Facebook users on the right and left shared very few common interests.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

We live in an age of dichotomy in America.

The rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer.

We have more means of communication, but there is a pandemic of loneliness.

We have unprecedented access to information, but we seem to know less, from civics to the history of the country.

We are beginning to see artificial intelligence displacing white-collar workers in many sectors, but there is a crying shortage of skilled workers, including welders, electricians, pipe fitters and ironworkers.

If your skill involves your hands, you are safe for now.

New data centers, hotels and mixed-use structures, factories and power plants are being delayed because of worker shortages. But the government is expelling undocumented immigrants, hundreds of thousands who have skills.

Thoughts about dichotomy came to me when Adam Clayton Powell III and I were interviewing Hedrick Smith, a journalist in full: a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter and editor, an Emmy Award-winning producer/correspondent and a bestselling author.

We were talking with Smith on White House Chronicle, the weekly news and public affairs program on PBS for which I serve as executive producer and co-host.

The two dichotomies that struck me were Smith's explanation of the decline of the middle class as the richest few rise, and how Congress has drifted into operating more like the British Parliament with party-line votes than the body envisaged by The Founders.

Echoing Benjamin Disraeli, the great British prime minister who said in 1845 that Britain had become “two nations," rich and poor, Smith said: “Since 1980, a wedge has been driven. We have become two Americas economically."

On the chronic dysfunction in Congress, Smith said: “When I came to Washington in 1962, to work for The New York Times, budgets got passed routinely. Congress passed 13 appropriations bills for different parts of the government. It happened every year."

This routine congressional action happened because there were compromises, he said, noting, “There were 70 Republicans who voted for Medicare along with 170 Democrats. (There was) compromise on the national highway system, sending a man to the moon in competition with the Russians. Compromise on a whole slew of things was absolutely common."

Smith remembered those days in Washington of order, bipartisanship and division over policy, not party. There were Southern Democrats and Northern Republicans, and Congress divided that way, but not routinely by party line.

He said, “There were Gypsy Moth Republicans who voted with Democratic presidents and Boll Weevil Democrats who voted with Republican presidents."

In fact, Smith said, there wasn't a single party-line vote on any major issue in Congress from 1945 to 1993.

“The Founding Fathers would never have imagined that we would have what the British call ‘party government.' Our system is constructed to require compromise, while we now have a political system that is gelled in bipartisanship."

On the dichotomy between the rich and the poor, Smith said that in the period from World War II up until 1980, the American middle class was experiencing a rise in its standard of living roughly keeping up with what was happening to the rich.

But since 1980, he said, “The upper 1 percent, and even the top 10 percent, have been soaring and the rest of the country has fallen off the cliff."

This dichotomy, according to Smith, has had huge political consequences.

In 2016, he said, Donald Trump ran for president as an advocate of the working class against the establishment Republicans: “He had 15 Republican (contenders) who were pro-business; they were pro-suburban Republicans who were well-educated, well-off. Trump had run on the other side, trying to grab the people who were aggrieved and left out by globalization. But we forget that," he said.

Smith went on to say that Bernie Sanders, the Democratic presidential candidate in 2016, did the same thing: “He was a 70-year-old, white-haired socialist who came from Vermont, with its three electoral votes, but he ran against the establishment candidate, Hillary Clinton ... and he damn near took the nomination away from her."

Smith said that result showed “there was rebellion against the establishment."

That rebellion, in my mind, has resulted in a worsening separation between and within the parties. They aren't making compromises which, as in times past, would offer a way forward.

A final dichotomy: The United States is the richest country the world has ever seen, and the national debt has just reached $38 trillion dollars.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS and an international energy-sector consultant.

Horizontal game

On Oct. 12, 1914, during the third game of the 1914 World Series between the National League’s Boston Braves and the American League’s Philadelphia Athletics at Fenway Park. The Braves won the series, 4-0. They had abandoned their 43-year-old home field, The South End Grounds, in August that year, choosing to rent from the Red Sox’ Fenway while construction proceeded on Braves Field, which opened in 1915. Thus their home games in this series were also at Fenway.

The public back then loved wide-angle shots like this.

‘Sketch, Shade, Smudge’

“Woman Seated by an Easel’’ (1882-1884), by Georges Seurat, (1859-1891), in the show “Sketch, Shade, Smudge: Drawing From Gray to Black,’’ at the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Mass.

Chris Powell: Ex Conn. official’s trial evokes musical comedy

MANCHESTER, Conn.

At his federal trial this month was Konstantinos Diamantis, who once doubled as deputy state budget director and chief of state government's school-construction office, really trying to defend himself against bribery and extortion charges, or was he actually auditioning for a revival of the Broadway musical Fiorello?

The play humorously depicts the crusade against corruption that was waged nearly a century ago by New York City's reformist mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia. Diamantis' explanation of his work in the school-construction office would have fit right in.

According to Diamantis, he wasn't shaking down contractors for kickbacks. No, he was charging them finder's fees for introducing them to people who might be helpful to their companies. The contractors didn't see it that way. Some already had pleaded guilty to paying him the bribes he demanded, understanding the payments as the condition for getting the state construction work.

Diamantis's testimony could have been turned into another verse in “Little Tin Box,” the cleverest song from Fiorello, which consists of courtroom exchanges between a grand jury judge and corrupt city employees testifying before him.

It's surprising that Diamantis's jury needed a day and a half before deciding that his story was suitable for musical comedy and convicting him on all 21 charges. But there won't be much humor in the long prison sentence he's facing.

Lately there has been a lot of sleaze if not outright corruption in state government, the consequence of longstanding one-party rule.

Among other things, the chairwoman of the Public Utilities Regulatory Authority resigned upon being caught lying to the legislature, a court, and the public. Legislators have been caught stuffing expensive “earmarks" into the state budget to benefit nominally nonprofit organizations run by their friends. The former public college system chancellor was dismissed but is getting a year of severance worth nearly $500,000 after being caught abusing his expense account, and he is guaranteed another comfortable public college job when his severance expires.

State government is a big place and some of its denizens will always cheat and steal. While Gov. Ned Lamont is as political as any other governor, he is not corrupt; he sometimes has been badly served by those he trusted.

But it is starting to seem as if Connecticut could use its own Fiorello LaGuardia to run a perpetual grand jury investigating corruption and malfeasance in state government. Federal -- not state -- prosecutors investigated Diamantis, and the General Assembly still refuses to examine government operations, confident that there will always be plenty of money for the little tin box.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).