Take cover

“The Cloud” (circa 1930, oil on canvas), by John Steuart Curry (1887-1946), at Southern Vermont Arts Center, Manchester.

‘Dissolving the boundaries’

From Eastefania Puerta's show “Laughing Death Drive’’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Conn., to Jan. 11, 2026.

The museum says:

“Born in Colombia and raised in East Boston, Puerta channels her experience growing up undocumented into a practice that redefines categorization—dissolving the boundaries between alien and natural, comforting and threatening, spoken and withheld. Influenced by literature, mythology, and psychoanalysis, she explores themes of shapeshifting and transformation, reflecting on what is gained or lost through cultural and material translation.’’

William Morgan: An Arizona developer’s dream of London Bridge in the desert

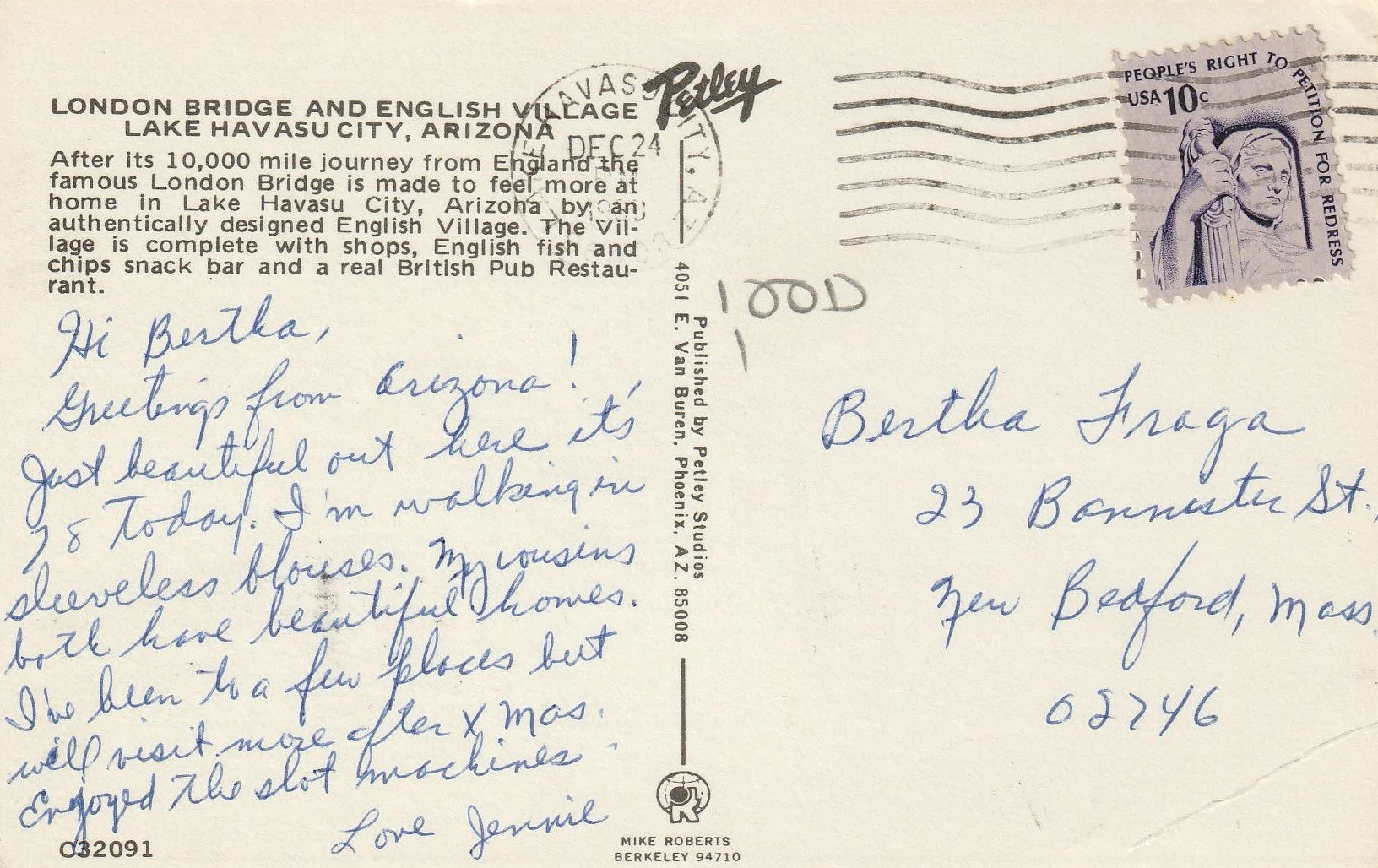

On Christmas Eve in the late 1970s, Jennie wrote a postcard to her friend Bertha Fraga back home, in New Bedford, Mass. There’s a bit of Schadenfreude on Jennie’s part: Bertha’s address is a triple decker in a run-down area just a block from Interstate Route 195.

As opposed to gray skies and snow flurries in the old whaling port, it is “Just beautiful out here it’s 78 today. I’m walking in sleeveless blouses. Both my cousins have beautiful homes.”

Jennie probably visited the Grand Canyon while on her trip, but her postmark puts her at Arizona’s second-most-popular tourist spot, London Bridge.

The Lake Havasu City bridge was purchased a decade before by a local businessman for $2.5 million, spending another $7 million to get the famous l830s landmark shipped from the Thames to the lake and reconstructed. (The Lord Mayor of London traveled to lay the cornerstone.)

London Bridge in Lake Havasu City, Ariz.

While undoubtedly an urban myth, there was some speculation that the Arizona developer believed that he was purchasing the much larger and far more ornate Tower Bridge. As it was, only the external granite blocks of London Bridge were taken to the Arizona site, next to the Colorado River, where they were attached to a new steel and concrete frame.

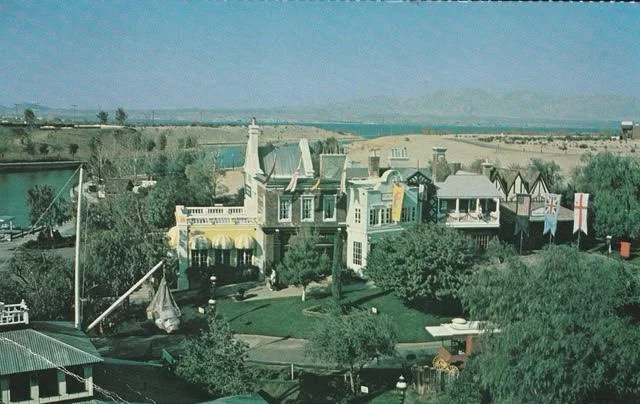

English Village at Lake Havasu City.

In trying to increase the visitor appeal of his planned city, the developer constructed “an authentically designed English village” to make the London Bridge “feel more at home.” Looking like a movie set from an old Western, the village boasted an “English fish and chips snack bar and a real British Pub Restaurant.”

Not surprisingly, the village expanded, as, promoters say, “local entrepreneurs and dreamers saw its potential and reimagined the space as a hub of family fun and entertainment.” Hit this link.

The Hog in Armor pub is now a microbrewery. As official Lake Havasu PR asserts, “the English Village remains a beloved destination for making memories … and feeling the magic of reinvention done right.”

Jennie may have been dazzled by the desert sun and the English Village’s cute shops, but score points to Bertha for living in an architecturally rich town with real, unmanufactured history.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural critic and historian and photographer. He has been contributing stories on New England’s quirky heritage to New England Diary for years. His book The Almighty Wall is about architect Henry Vaughan, who designed the original building of the Whaling Museum in New Bedford.

Nicholas Jacobs: Maine’s hyper-controversial Graham Platner in context

Graham Platner

Nicholas Jacobs is Goldfarb Family Distinguished Chair in American Government at Colby College, Waterville, Maine.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

WATERVILLE, Maine

From The Conversation, except for images above.

Every few years, Democrats try to convince themselves they’ve found the one – a candidate who can finally speak fluent rural, who looks and sounds like the voters they’ve lost.

In 2024, that hope was pinned on Tim Walz, the flannel-wearing, “Midwestern nice” governor whose small-town roots were supposed to unlock the rural Midwest for a Harris–Walz victory.

Now those expectations have migrated to New England, onto Graham Platner – the tattooed veteran and oyster farmer from Maine who swears from the stump, wears sweatshirts instead of suits, and, some believe, could be the party’s blue-collar savior against U.S. Sen. Susan Collins, the Republican incumbent running her sixth campaign for the Senate.

I study rural politics and live in rural Maine. I’m skeptical whether Platner can reach the independents and rural moderates Democrats need. But I also see why people think he might: He’s speaking to grievances that are real, measurable and decades in the making.

Platner represents Democrats’ anxieties about class and geography – a projection of the authenticity they hope might reconcile their national brand with rural America. On paper, he’s the kind of figure they imagine can bridge the divide: a plainspoken Mainer.

But his story cuts both ways. He’s the grandson of a celebrated Manhattan architect; his father is a lawyer, and his mother is a restaurateur whose business caters to summer tourists. He attended the elite Hotchkiss School.

It’s a life of silver spoons and salt air. That tension mirrors the Democratic party itself, led and funded by urban professionals who are increasingly aware of just how far they strayed from their working-class roots.

If Platner is to prevail, he must assemble a coalition that expands beyond what the party has become – concentrated in urban and coastal enclaves, financed nationally and culturally distant from much of rural America.

Yet Platner’s immediate hurdle isn’t rural Maine at all. It is the Democratic primary, and those voters do not live where his campaign imagery is set.

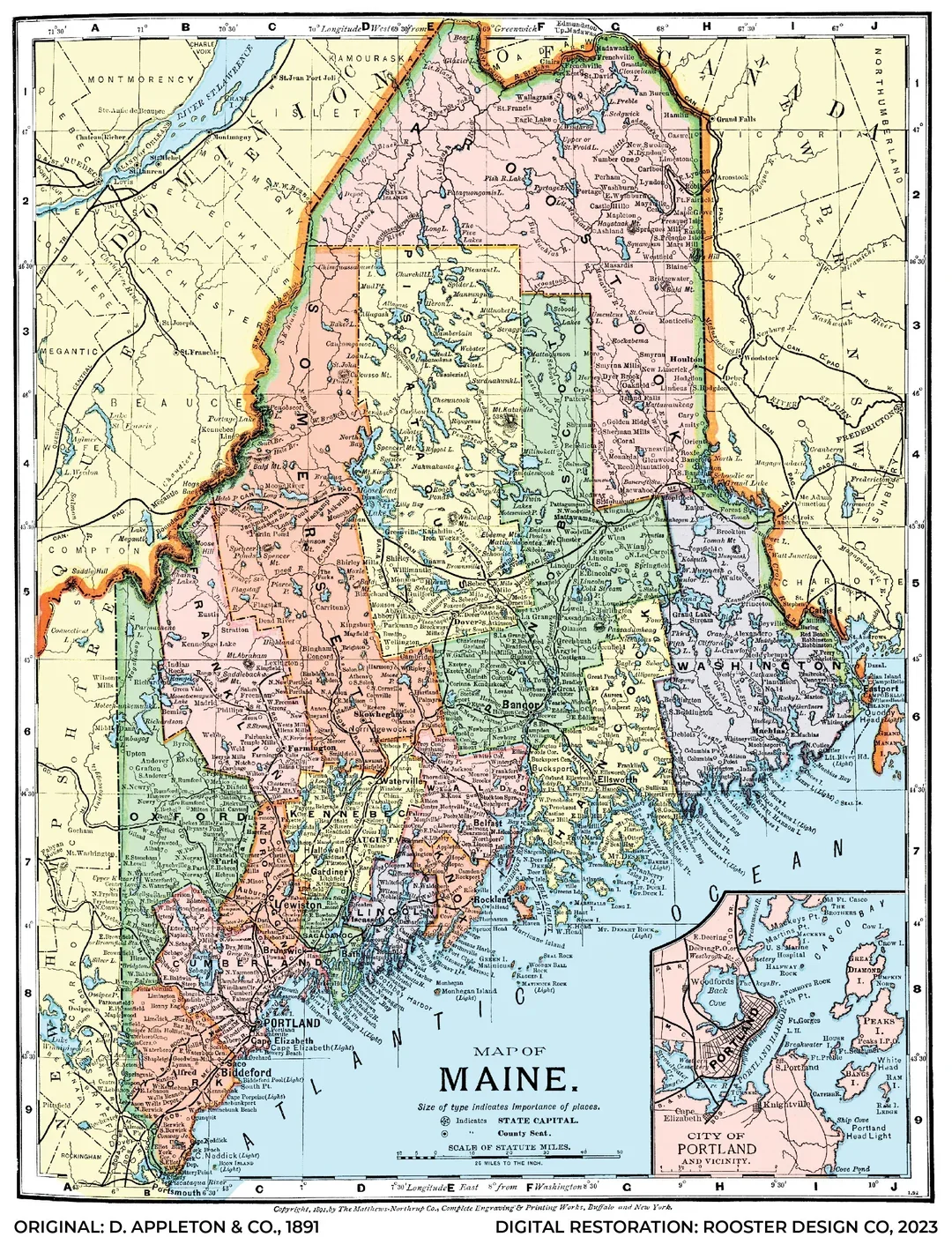

Opportunity zone

In 2024, nearly 6 in 10 registered Democrats in Maine lived south of the state capital Augusta. That part of the state would not constitute an urban metropolis anywhere else in the U.S., but it is a drastically different world than the one Platner is fighting for.

The party’s gravitational center sits in Cumberland and York counties: Greater Portland and the southern coastal strip. That electorate is more educated, affluent and urban than the state as a whole, clustered in Portland’s walkable neighborhoods, college towns such as Brunswick and artsy coastal communities that swell with summer tourists.

Southern Maine – closer in feel to Boston’s suburbs than to the paper mills and potato fields up north – is where Democrats are already strong. Collins’s vulnerability lies instead among independents in small cities and towns, in deindustrialized and rural counties drifting rightward for two decades.

The 2020 U.S. Senate race – one that nearly every analyst, myself included, thought Collins was doomed to lose to Democrat Sara Gideon – makes that reality clear.

Collins outperformed Donald Trump in every county. She built commanding margins in rural Maine, offsetting Democratic gains in Portland and the southern coast. Her real breakthrough came in the kinds of small towns where Trump lost and she won or closed the margin: Ellsworth, Brewer, Machias, Gardiner and Winterport.

Those former mill towns and service hubs once anchored the Maine Democratic Party. They’re home to exactly the kinds of voters who, in principle, might give someone like Platner a hearing: not deeply ideological, modestly skeptical of both parties and wary of national polarization.

But they are also the voters least represented in the Democratic primary electorate or the donor class fueling Platner’s campaign.

Doing it as a Democrat

According to the most recent Federal Election Commission figures, only about 12% of Platner’s haul has even come from inside Maine. The nationalization of campaign finance is becoming more common for U.S. Senate candidates.

But there are two differences worth noting.

Platner’s in-state share is higher and more geographically diffuse than Gideon’s 2020 campaign. Then, in what became Maine’s most expensive Senate race, just 4% of Gideon’s war chest was homegrown. Most of that Maine money was heavily concentrated in Portland and the southern coastal corridor.

While 64% of Gideon’s Maine total fundraising amount came from the three southernmost counties, 88% of Platner’s current in-state funding is from outside the urban-suburban core of southern Maine.

That divergence matters. It suggests that while Platner’s campaign is still fueled by national money, its local base – however small – extends beyond the usual Portland orbit.

And there is a reason Platner’s message has not been dead on arrival.

The economic populism he’s advancing speaks directly to the material frustrations many rural residents express – frustration with corporate consolidation, rising costs and the feeling that prosperity never reaches their communities.

The 2024 Cooperative Election Study shows that rural independents and moderates often share progressive instincts on precisely these issues:

Large majorities of rural, moderate/independent New Englanders support higher taxes on the wealthy and expanded health coverage. Platner is emphasizing those issues – corporate power, health costs, infrastructure, wages – where the urban–rural divide is narrowest.

Platner may be closing that gap. In an October 2025 survey, 58% of likely Democratic primary voters named him as their first choice for the 2026 Senate nomination. While that support has likely changed in the aftermath of two controversies – his chest tattoo that resembled a Nazi icon and recent posts on Reddit, including one in which he says rural people “actually are” “stupid” and “racist” – that poll’s most notable finding is the consistency of support across income and education levels.

Still, while his message may bridge income and education, the biggest obstacle facing Platner is the simplest one: He’s trying to do all of this as a Democrat.

Hearing, not speaking

Being anchored in metropolitan and professional networks far removed from rural life shapes not only what Democrats stand for but how they speak, focusing on moral and cultural commitments that resonate nationally but feel abstract in smaller, locally based communities.

That’s why even an economically resonant message struggles once it meets the national brand.

Rural independents and moderates often agree with Democrats on taxes, health care and wages. Those alignments fade when policy is framed through the institutions and moral language of a party many no longer see as compatible with rural ways of living.

It’s not clear yet how Platner will respond on issues that don’t poll well in rural Maine – environmental regulation, gun control or immigration – where loyalty to the national agenda has undone many would-be reformers before him.

And that schism is not because rural voters misunderstand their “self-interest” or because racial dog whistles have led them astray. It is hostility toward a party that, with rare exception, sees the future as something rural America must adapt to, not something it should help define.

That is the danger of treating biography as the solution to a decades-long realignment. Platner might be as close as Democrats have come in years to a candidate who can talk credibly to rural voters about power, place and policy. But he still has to do it while wearing the “scarlet D” – the weight of a party brand built over generations.

Whether he wins or loses, his campaign already points to a deeper question: Can Democrats do more than rent rural authenticity? Put more bluntly, the real test is not whether Platner can speak to rural Maine, it is whether his party can finally learn to hear it.

Time to clear out?

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Does New England have more in common with Ontario, Quebec and the Maritime Provinces than with, in particular, the Deep South? I’d say yes.

Which gets me to Colin Woodard’s new book, Nations Apart: How Clashing Regional Cultures Shattered America.

The book’s most interesting themes are how old and entrenched these cultural, political and economic differences are, and that they’re unlikely to be bridged. Knowing the backgrounds of those who took over these regions from the Native Americans is crucial in understanding these “nations.’’ Think of New England’s Puritans, New York’s Dutch and Appalachia’s Scotch-Irish. Mr. Woodard eloquently discusses why the richest, and what you might call the most “civilized’’ and humane, parts of the U.S. do so well and Appalachia and the Deep South so poorly.

Maybe it’s time to get it over with and split up the country.

After ‘civilization’

“Rewilding’’(acrylic on canvas), by Marli Thibodeau, in her show “Art & Wine, at Gallery Sitka, Newport, R.I., through Dec. 12.

Chris Powell: Designed to prohibit housing affordability

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Perhaps taking a hint from socialist Democrat Zohran Mamdani's successful campaign for mayor of New York City, whose slogan was “A city we can afford," politicians in both parties in Connecticut are taking “affordability" for their own platforms.

Some Connecticut Democrats, including Gov. Ned Lamont, have even attributed their party's success in this month's municipal elections to a supposed commitment to affordability. This is laughable. Far more votes were probably pushed toward the Democrats by the political chaos in Washington than by any achievement in “affordability" in Connecticut, though the six-week partial shutdown of the federal government was an entirely Democratic stunt, not President Trump's doing.

Yes, Connecticut's Democratic state administration hasn't raised taxes much lately, but municipal property taxes still go up because state law and policy determine much of how municipalities spend their money. These days there's not much difference between state and municipal finance.

Greenwich state Sen. Ryan Fazio, a candidate for the Republican nomination for governor next year, pressed the “affordability" theme in response to Lamont's declaration of candidacy for a third term.

“Governor Lamont's first eight years in office," Fazio said, “have seen Connecticut's electricity rates rise to the third-highest in the nation, and our economic growth plummet to fourth worst in the country. Families are struggling to make ends meet, while people and jobs are leaving our state. … I am running for governor to make our state more affordable and safe and create opportunities for all."

Connecticut's increasing unaffordability has been caused to a great extent by the explosion of federal spending and debt, for which the state's members of Congress, all Democrats, share responsibility.

But much of Connecticut's unaffordability is also caused by the state's own law and policy. Indeed, state law and policy virtually prohibit affordability by preventing ordinary efficiency in government, and affordability will never be achieved if this isn't spelled out.

For example, Connecticut didn't enact collective bargaining for government employees and binding arbitration for their union contracts in pursuit of affordability. Collective bargaining and binding arbitration for government employees had the effect of driving up government's costs, relieving elected officials of difficult responsibility, and sustaining a powerful special interest that serves as the army of the majority party, the Democrats.

These laws forbid ordinary democratic control and accountability in public administration.

Connecticut didn't enact its minimum budget requirement for school systems in pursuit of affordability. The minimum budget requirement, which virtually prohibits economizing in school systems even if student enrollment falls substantially, was enacted to ensure that any financial savings in schools would be transferred to school employees, particularly teachers, rather than refunded to taxpayers.

Nor did Connecticut enact its “public benefits charges" -- essentially taxes on electricity -- to make life in the state more affordable but to conceal the costs of welfare and “green" energy programs in electricity bills so people would blame the electric utilities for electricity's high cost, though the utilities, at the command of state law, stopped generating electricity years ago and now only distribute it.

At least Republican state legislators, a small minority in the General Assembly, recently made an issue of the “public benefits charges" and the majority Democrats found them hard to defend, so some were removed from electric bills. But they were not eliminated. Instead state government now is paying for the “public benefits" with bond money, which will cost state residents even more in the long run.

The “public benefits charges" were an easy target. The special interests dependent on them, welfare recipients and self-styled environmentalists, are not so influential. But collective bargaining and binding arbitration for state and local government employees have huge special-interest constituencies, as does the minimum budget requirement for schools.

Those anti-affordability laws are far more expensive than the “public benefits charges," and no politician is likely to criticize them, though there will be little affordability in the state until they are repealed or reduced in scope.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

When the Red States attacked

“Our Banner in the Sky” (1861 oil painting), by Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900).

This painting by Church, a Connecticut native, was his political statement in defense of the Union when the Confederate attacked Fort Sumter, S.C., in April 1861, launching the Civil War. The vivid orange sky represents the Union flag with a bare tree stick as the flagpole.

Sustainable-fishing project off New Hampshire

AquaFort structure off the New Hampshire coast.

Edited from a New England Council report

The University of New Hampshire is advancing its AquaFort seafood system in producing more local fish at its facility off the coast of New Castle, N.H. AquaFort is part of UNH’s Center fo Sustainable Seafood Systems.

The 28 by 52-foot floating structure raises steelhead trout in a system that naturally filters waste through kelp and mussels, creating a sustainable cycle that helps both the environment and fishermen. Researchers believe that it could bring more stability to the local fishing business and allow for a much smaller human footprint.

Hard work

“Quarryman Joe Boston” (1930 oil on canvas), by Samuel Lewis Pullman (1900-1961), in the show “Hammers on Stone — The Granite Industry & Cape Ann,’’ at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, Mass., through Feb. 1. Stone quarrying was a major industry in parts of New England for hundreds of years.

The show explores the history, artistry and impact of Cape Ann's granite-quarrying industry through what the museum's calls its “extensive holdings of objects and archival materials related to the industry.’’

The granite went into roads, buildings and other construction all over the world.

Llewellyn King: Can the elephant of AI become capable of policing itself?

Street art in Tel Aviv.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

For me, the big news isn't the politics of the moment, the deliberations before the Supreme Court or even the news of the battlefront in Ukraine. No, it is a rather modest, careful announcement by Anthropic, the developer of the Claude suite of chatbots.

Anthropic, almost sotto voce, announced it had detected introspection in their models. Introspection.

This means, experts point out, that artificial intelligence is adjusting and examining itself, not thinking. But I don't believe that this should diminish its importance. It is a small step toward what may lead to self-correction in AI, taking away some of the craziness.

There is much that is still speculation — and a great deal more that we don't know about what the neural networks are capable of as they interact.

We don't know, for example, why AI hallucinates (goes illogically crazy). We also don't know why it is obsequious (tries to give answers that please).

I think that the cautious Anthropic announcement is a step in justification of a theory about AI that I have held for some time: AI is capable of self-policing and may develop guidelines for itself.

A bit insane? Most experts have told me that AI isn't capable of thinking. But I think Anthropic's mention that introspection has been detected means that AI is, if not thinking, beginning to apply standards to itself.

I am not a computer scientist and have no significant scientific training. I am a newspaperman who never wanted to see the end of hot type and who was happier typing on a manual machine than on a word processor.

But I have been enthralled by the possibilities of AI, for better or worse, and have attended many conferences and interviewed dozens — yes, dozens — of experts across the world.

My argument is this: AI is trained on what we know, Western Civilization, and it reflects the biases implicit in that. In short, the values and the facts are about white men because they have been the major input into AI so far.

Women get short shrift, and there is little about people of color. Most AI companies work to understand and temper these biases.

While the experiences of white men down through the centuries are what AI knows, there is enough concern about that implicit bias that it creates a challenge in using AI.

But what this body of work that has been fed into AI also reflects is human questioning, doubt and uncertainty.

At another level, it has a lot of standards, strictures, moral codes and opinions on what is right and wrong. These, too, are part of the giant knowledge base that AI calls upon when it is given a prompt.

My argument has been: Why would these not bear down on AI, causing it to struggle with values? The history of all civilizations includes a struggle for values.

We already know it has what is called obsequious bias: For reasons we don't know, it endeavors to please, to angle its advice to what it believes we want to hear. To me, that suggests that something approximating the early stages of awareness is going on and indicates that AI may be wanting to edit itself.

The argument against this is that AI is inanimate and can't think any more than an internal combustion engine can.

I take comfort in what my friend Omar Hatamleh, who has written five books on AI, told me: “AI is exponential and humans think in a linear way. We extrapolate."

My interpretation: We have touched an elephant with one finger and are trying to imagine its size and shape. Good luck with that.

The immediate impact of AI on society is becoming one of curiosity and alarm.

We are curious, naturally, to know how this new tool will shape the future as the Industrial Revolution and then the digital revolution have shaped the present. The alarm is the impact it is beginning to have on jobs, an impact that hasn't yet been quantified or understood.

I have been to five major AI conferences in the past year and have worked on the phones and made several television programs on AI. The consensus: AI will subtract from the present job inventory but will add new jobs. I hope that is true.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy consultant.

@llewellynking2

William Morgan: Why we need writing on architecture

Conversion and expansion of the old Miriam Hospital, in Providence’s Armory District, into apartments. Jack Ryan is its architect. He was recognized with two awards at this year’s AIA-RI annual dinner.

— Photos by William Morgan

Remarks on receiving the ARCHISTAR award from the Rhode Island chapter of the American Institute of Architects at its annual on Nov. 6.

Some years ago, a visitor to my mother’s home, saw one of my books on the coffee table. and declared, “William Morgan. He’s a famous architectural historian.” “No, he’s not” my mother replied, “He’s my son.”

So, it is nice to be recognized. Thank you, AIA – Rhode Island.

When I was the age that kids dream of future careers as astronauts, brain surgeons, or firemen, did I want to grow up and be an architecture critic? No. But from the first lecture in Art 1 in college, I knew my life would be in architecture. Torn tracing paper at Columbia’s architecture school demonstrated that my path would not be as a designer. So, instead I became an historian, and, I hope, an advocate for the role of good architecture.

My wife, Carolyn, and I chose to move to Providence over 25 years ago. We had a list of what might be our ideal places, but we came largely because the city was so rich architecturally, so damned attractive, so human-scaled. (We were snowed by the idea that the city was removing the I-195 overpass from downtown.)

While teaching in the architecture school at Roger Williams University, I started writing for The Providence Journal. I also spent a couple of years as architecture critic for Art New England. (I was let go when I refused to remove the line that “Brown had the lowest architecture I.Q. in the Ivy League” from an article about Rafael Viñoly’s Watson Institute building.) Many of you may know me from my dozen or so years with GoLocalProv.com. I also wrote for Design New England’s entire run, until The Boston Globe decided to shutter the award-winning magazine.

Architectural writing of any kind is more important than ever. The Mother of the Arts is being marginalized, and there needs to be more conversation, more public discussion of the built environment. There have been so many losses, so many failures.

For example, the stupidity of the I-195 makeover of a big chunk of downtown Providence – a tremendous civic opportunity that has been squandered. The bland leading the bland. Not to mention the victory of architecturally illiterate developers, and the triumph of the second-rate.

Good architecture has to compete with, and often cede ground, to “design build,” or building plans available on the Internet for a few dollars. And then there is the challenge of Artificial Intelligence.

If your aim is only to monetize your abilities –that is, if the bottom line is always more important than aspirations or art, you are bound to lose what really matters. And what about the inability of government to maintain bridges and roads, much less plan an intelligently constructed and well-designed commonweal?

Trump’s destruction of the East Wing of the White House should remind us of political leaders who understood place and symbol-making. Harry Truman insisted that a crumbling people’s building had to be restored, not replaced. Woodrow Wilson, who designed his own Tudor revival house, did much to create the Collegiate Gothic campus as president of Princeton University.

(The original East Wing was built in the early 19th Century and later torn down, while the version Trump demolished was constructed under Franklin Roosevelt in 1942 with the design by government architect Lorenzo Winslow.)

FDR not only designed his presidential library, in Hyde Park, N.Y., and the wooden case for the East Room piano, but wrote about Dutch Colonial architecture in the Hudson Valley.

And, of course, Thomas Jefferson, who was not only the brightest man in the land, but who believed in architecture’s fundamental role in defining our republic. Like it or not, we will be judged by our buildings.

The design profession – rather than politicians, contractors, or money men–needs to become the voice of planning that lifts the city and landscape out of the doldrums of mediocre vision into buildings and spaces that support human connection and raise the human spirit.

Thank you for this award, and for all that you do to fight the battle for good architecture.

Architectural historian, critic and photographer William Morgan’s books include Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States and The Cape Cod Cottage

Block Island house by Estes Twombly Architects, the Newport practice with probably more AIA-RI awards than any other firm.

Chris Powell: Special-interest politics support “nips’’ pollution

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Next time you come upon empty and discarded “nip" bottles -- the tiny plastic containers of liquor sold in abundance at Connecticut's liquor stores but neither returnable for deposits nor recyclable -- Larry Cafero wants you to be thankful.

Cafero, executive director of the Connecticut Wine and Spirit Wholesalers, announced the other day that the 5-cent de-facto tax on nip bottles has generated more than $19 million since it began four years ago, with the money distributed by the state to municipalities in proportion to the number of “nips" sold in each. Municipal governments are to use the money for environmental-cleanup purposes.

The problem is that only a little of the money is used to recover the discarded nip bottles themselves. Such an undertaking would be extremely labor-intensive. Instead municipalities use the money to run recycling centers or other programs to reduce litter or protect the environment.

So the nip bottles keep defacing streets, parks, and the countryside, being collected only partially and put in trash cans by people who go for nature walks and are disgusted by Connecticut's policy of letting nature be defaced so a special interest can keep making money off a product that has only pernicious effects -- the strewing of unbiodegradable trash throughout the state and the facilitation of drunken driving and underage drinking.

Other than gratifying the liquor industry, there is no need for this stuff. Connecticut could forbid the sale of nip bottles, as alcoholism-riddled New Mexico does, or impose on them a cash deposit high enough to induce their buyers to return them to the liquor stores or induce everyone else to pick them up and return them for the deposits.

Instead of a “nickel a nip" a dollar a nip might work beautifully.

But while the liquor stores use the “nickel a nip" program to pose as civic-minded, they don't really want to reduce the litter they cause. They complain that their taking the empty nip bottles back and refunding deposits would take up too much space in their stores and require too much additional labor. The liquor stores want littering, drunken driving, and underage drinking to remain profitable for them but costly for society.

Cafero says it would be unfair to change anything about nips because liquor store owners got into their business on the presumption they could sell the products. But that's a rationalization for prohibiting all changes involving business, changes involving taxes, pollution control, consumer protection, public safety, wages, and protections for labor. No other businesses in Connecticut have such privilege. All other businesses are always subject to new laws that change business conditions.

Besides, Connecticut's liquor industry already enjoys outrageous privilege -- state law establishing minimum prices for alcoholic beverages, a law that protects liquor stores against the ordinary competition all other businesses face.

The law against price competition in liquor long has given Connecticut some of the highest liquor prices in the country. It is essentially a tax whose revenue goes not to state government but to the liquor stores and wholesalers themselves.

Why does Connecticut allow such exploitation of the public?

It's all special-interest politics.

Most legislative districts have a dozen or more liquor stores profiting from this exploitation and the stores have an active trade association. With Cafero the liquor stores have hired a former legislative leader, and, if their privileges are ever threatened, store owners and their employees will show up at hearings or rallies to intimidate legislators.

Meanwhile, news organizations, in financial decline, won't investigate and report the sordid details of the liquor business in Connecticut lest they risk losing liquor advertising, and the public, ever more impoverished by inflation and other failing government policies, seems increasingly content just to drink itself silly at home or, worse, on the road.

All this littering, drunken driving, and underage drinking should be worth a lot more to state government than $19 million in four years, or less than $4 million per year. Its cost is much higher than that and it's nothing to celebrate.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

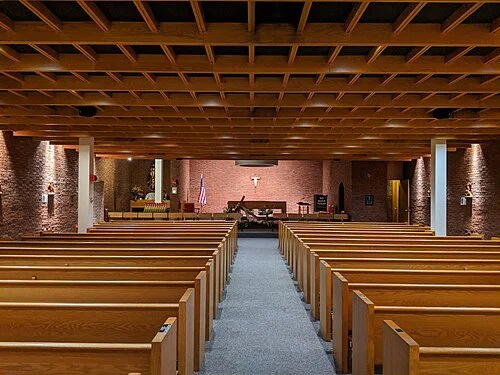

Material for a writer

Our Lady of the Airways Chapel, at Logan International Airport. It’s the oldest airport chapel in the United States. It first opened in 1951, in another part of the airport.

“Strangely enough, my favorite airport is Logan Airport, in Boston - but largely for sentimental reasons. My first real summer job was working as a journeyman for the airport's resident maintenance crew - a small army of union electricians, plumbers, and carpenters.’’

— Amor Towles, novelist

Before the hedge-funders

‘‘Island Hay” (1945 lithograph), by Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975) in the show “Pressing Editions: American Labor in Print,’’ at the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass. The island referred to here is Martha’s Vineyard, where Benton spent much time.

The museum says that the show aims to explore how printmaking has “enabled artists and audiences to explore urgent issues of labor in the United States. Juxtaposing historical work with that of contemporary artists Sean Flood, Nina Montejano, and Adrian Tió, ‘Pressing Editions’ presents a timely dialogue on art as work. And artists both historical and contemporary present scenes of local industry, portraits of workers of diverse backgrounds, and reflections on the work that goes into their various art-making processes.”

Céline Gounder: Of covid-19 and pregnancy

Woman in third trimester of pregnancy

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (except for image above)

A large study from Massachusetts has found that babies whose mothers had covid-19 while pregnant were slightly more likely to have a range of neurodevelopmental diagnoses by age 3. Most of these children had speech or motor delays, and the link was strongest in boys and when the mother was infected late in pregnancy.

The increase in risk was small for any one child, but because millions of women were pregnant during the pandemic, even a small increase matters. The study doesn’t prove that covid infection during pregnancy causes autism or other brain conditions in the fetus, but it suggests that infections and inflammation during pregnancy can affect how a baby’s brain grows, something scientists have seen before with other illnesses. It’s a reason to help pregnant women avoid covid and to keep a close eye on children who were exposed in the womb.

What the Study Found

Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital examined medical records from more than 18,000 mothers and their children born from March 2020 through May 2021, before vaccines were widely available to pregnant women. Because everyone giving birth during that period was tested for covid, the team could clearly see which pregnancies were exposed to the virus causing it.

About 5% of those mothers had covid while pregnant. Their children were modestly more likely to be diagnosed with a neurodevelopmental condition by age 3 than those whose mothers weren’t infected, even after accounting for differences in maternal age, race, insurance status, and preterm birth.

The link appeared strongest among boys and when infection occurred in their mother’s third trimester. Still, most children in both groups showed typical development.

“This was a very clean group to follow,” said Andrea Edlow, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Mass General and one of the study’s authors. “Because of universal testing early in the pandemic, we knew who had covid and who didn’t.”

Independent authorities say covid, which causes a powerful immune response in some people, fits the biological pattern seen with other infections in pregnancy. Alan Brown, a professor of psychiatry and epidemiology at Columbia University who studies maternal infection and brain development and was not involved in this research, explained, “Covid would be a very strong candidate for it to happen because the amount of inflammation is very extreme.”

How Might Infection Affect Brain Development?

Scientists are still piecing together how various infections during pregnancy can affect fetal development. Severe illness can cause inflammation that disrupts brain growth or can trigger preterm birth, which carries its own risks.

“There’s a long history of evidence showing that maternal infection can slightly raise the risk for many neurodevelopmental disorders,” said Roy Perlis, the vice chair for research in psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital and co-author of the new study.

Edlow’s lab is investigating how infection and inflammation may interfere with brain development. In a healthy brain, immune cells help shape developing neural circuits by trimming away extra or unnecessary connections, a process known as “synaptic pruning,” which sculpts the brain’s wiring. When a mother’s immune system is activated by infection, inflammatory molecules can reach the fetal brain and alter the pruning process.

Animal studies support Edlow’s hypothesis. When scientists trigger inflammation in pregnant mice, their offspring often show changes in how brain cells grow and connect, changes that can alter learning and behavior.

Why Late Pregnancy and Why Boys?

In Edlow and Perlis’s study, the link between covid and developmental delays was strongest when infection occurred late in pregnancy, during the third trimester. That’s also when the fetal brain is growing most rapidly, forming and refining millions of neural connections.

“When we think of organ development, we think earlier in pregnancy, but the brain is an exception in this regard, where there’s a massive amount of brain development in the third trimester. And that continues after birth,” Perlis said. “It is entirely plausible that the third trimester is a period of vulnerability specifically for brain development.”

But not all researchers agree that the third trimester is uniquely vulnerable. Brian Lee, a professor of epidemiology at Drexel University, cautioned that because most mothers in the study were tested at delivery, there were simply more late-pregnancy infections to analyze. “That gives the study more power to find a difference in the third trimester,” he said. “It doesn’t prove earlier infections aren’t important.”

The study also found stronger effects in boys. That pattern is familiar: Boys are generally more likely than girls to have speech or motor delays and to be diagnosed with autism. Researchers suspect that male fetuses may be more susceptible to stress and inflammation, though the biology isn’t fully understood.

What the Study Can and Can’t Show

Edlow and Perlis are careful to say the study shows an association, not proof that covid infection in pregnancy causes developmental problems. Many other factors could explain the correlation.

Mothers who get sick with covid may have other health issues, such as obesity, diabetes, or mental- health conditions, that increase the risk of developmental delays in children. “Persons with mental disorders are much more likely to get covid. Women with mental disorders are much more likely to have kids with neurodevelopmental problems,” Lee said. “Mothers with worse physical health are also at higher risk of having children with neurodevelopmental problems.”

Lee’s research has shown that even infections before or after pregnancy can be linked to autism, suggesting that shared genetics or environment, rather than the infection itself, could be at play.

That’s why experts say much larger, longer studies are needed to understand the extent of any risk from the infection.

Edlow, Perlis, and their team plan to follow the children in their study as they grow older to see whether early differences persist or fade. They’re also studying how inflammation during pregnancy affects the placenta and fetal brain, and how to counteract these effects.

What About Vaccination?

Because this study followed pregnancies from early in the pandemic, it doesn’t answer whether vaccination changes the risk. But other research offers reassurance.

A large national study in Scotland found no difference in early developmental outcomes between children whose mothers were vaccinated and those who weren’t. Another study in the U.S. found the same: no link between prenatal covid vaccination and developmental delays through 18 months. Both align with decades of data showing that vaccination during pregnancy is safe for both the mother and the baby.

“Vaccination is a short spike … your immune system revs up, then it goes back to normal,” Edlow said. “Covid [infection] is much more prolonged, unpredictable, and people can get … a dysregulated immune phenomenon that really doesn’t exist in vaccine responses.”

What This Means for Parents and Clinicians

Since late 2020, there’s been widespread confusion and misinformation about the safety of covid vaccination during pregnancy. Some women have hesitated to get vaccinated out of fear it might harm their baby. But the evidence since then has been clear: Covid vaccines are safe in pregnancy. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists strongly recommends covid vaccination to protect both mother and child.

Experts say the broader lesson is that pregnancy is a period of vulnerability, and prevention matters, not only for covid, but other infections as well.

Janet Currie, a professor of economics at Yale University, said these risks remain “underappreciated,” despite decades of evidence. “Even though the flu vaccine is recommended for pregnant women, very few pregnant women get it,” she said. “Physicians seem to be reluctant to vaccinate pregnant women.”

As Gil Mor, scientific director of the C.S. Mott Center for Human Growth and Development at Wayne State University, in Detroit, put it, “Protecting the mother is protecting the long-term health of the offspring. … The best intervention is vaccination.”

A Century-Old Echo

The idea that what happens in the womb can shape life after birth took root with studies of famine, like the Dutch “Hunger Winter” in the final months of World War II. In 1944 and 1945, as German forces blockaded the western Netherlands, rations fell to just a few hundred calories a day.

Thousands died of starvation, and women pregnant during that period gave birth to babies who later faced higher risks of heart disease, diabetes, and schizophrenia. The episode became a cornerstone of the “fetal origins” idea, that deprivation or stress in pregnancy can have lifelong effects.

The 1918 flu pandemic broadened that idea to infection. Babies exposed to influenza in utero later showed small but lasting differences in education and earnings, a sign that illness during pregnancy could affect brain development. Researchers in Taiwan, Sweden, Switzerland, Brazil, and Japan found similar consequences. Some argued that those findings reflected the disruptions of World War I, not the flu itself. But later studies, including those from the United Kingdom and Finland, have strengthened the case for a biological effect, reinforcing that the infection itself, not wartime upheaval, was the key driver.

“It isn’t simply influenza that can alter fetal neurodevelopment,” Kristina Adams Waldorf, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington, explained. “Many types of infections … in the mother can be transmitted as a signal to the fetus, which can alter its brain development.”

A century later, the same question has returned with covid: Could infection during pregnancy subtly shape how children grow and learn? The new Massachusetts General Hospital study offers an early look at an answer.

Céline Gounder is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter ( cgounder@kff.org).

Relat

‘Better for her praise’

“November Morning,’’ by Willard Metcalf (1858-1925), a Massachusetts native who did many paintings with New England settings.

My Sorrow, when she’s here with me,

Thinks these dark days of autumn rain

Are beautiful as days can be;

She loves the bare, the withered tree;

She walks the sodden pasture lane.

Her pleasure will not let me stay.

She talks and I am fain to list:

She’s glad the birds are gone away,

She’s glad her simple worsted gray

Is silver now with clinging mist.

The desolate, deserted trees,

The faded earth, the heavy sky,

The beauties she so truly sees,

She thinks I have no eye for these,

And vexes me for reason why.

Not yesterday I learned to know

The love of bare November days

Before the coming of the snow,

But it were vain to tell her so,

And they are better for her praise.”

“My November Guest,” by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

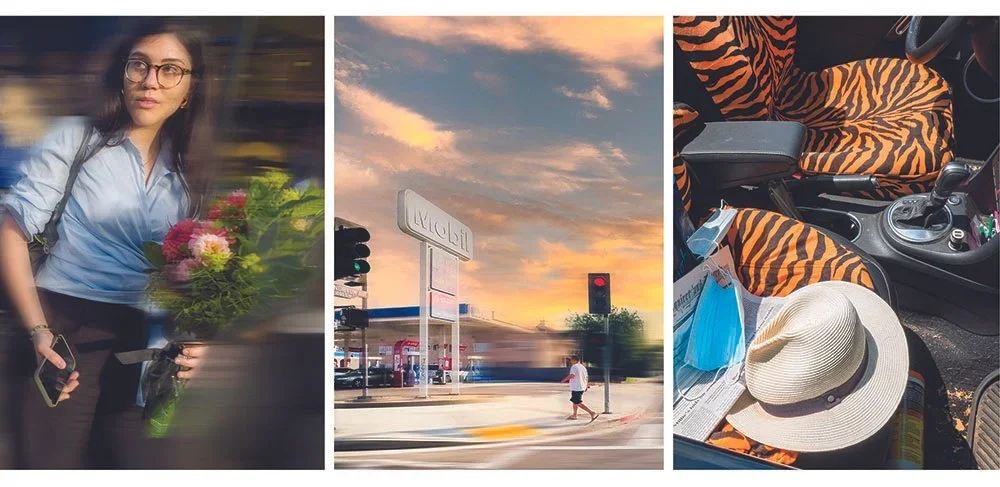

‘Anything that catches my eye’

From Gary Duehr’s show “People, Places, Things,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, Nov. 5-30.

He says:

“This retrospective skims across several decades of making photos, from People on the streets and squeezed into elevators; to Places behind the scenes or blurred by speed; to Things including messy car interiors and handwritten notes in public.

“A woman cradles flowers on a city street. Sunset sweeps across an LA intersection. A Panama hat and tiger-striped seat covers suggest a safari in Provincetown.

“There is often tension between the camera’s nailing of details and an expressive vision that grabs moments flitting by. The choice of subjects is expansive, even whimsical. To the typical question asked of photographers what they take pictures of, the answer here is: ‘Anything that catches my eye.’”