Tom Courage: What I learned about writing

My writing was certainly undistinguished at The Choate School, in Wallingford, Conn., as my teachers’ reports (which I still have) consistently indicate.

Mr. Gutterson revered E.B. White, and expected me to emulate the breezy, sophisticated froth of a New Yorker magazine “Talk of the Town’’ piece. Nothing could have been more ill-suited to my personality, as a foam-at-the-mouth head-first slide into home plate amidst a choking cloud of dirt is probably the best metaphor for my temperament.

In my term reports, Gutterson portrayed me as a student who combined awkward writing and earnestness. I must acknowledge in retrospect that I had achieved admirable fluency in all the cliches. One of my writing efforts is sufficient to illustrate this.

When I was about 13, my Greenwich, Conn., family moved from the Riverside section to Valley Road in the town’s Cos Cob section, on the shore of the Mianus River (above the dam, built by the power company to generate electricity for the New Haven Railroad ). One of the notable characters in our new neighborhood was an eccentric fellow everyone called Captain Horst, who collected stale bread from the bakeries and delivered it to residents up and down the river, to be fed to the swans.

My story was about Captain Horst, and more particularly about his arrest. Apparently he had been keeping goats in his living room, at odds with the strict dictates of the zoning ordinance of the Town of Greenwich.

Taken in the right direction, such a story might have been right up Mr. Gutterson’s alley.

Predictably, I took a different route, more along the “can’t we all be brothers?” pathway. In Mr. Gutterson’s eyes, I had taken a promising shiny nugget and transformed it into a lump of coal. It is easy to visualize Mr. Gutterson slapping his forehead. My report that term mentioned my steadfast (if boring) pursuit of values.

Mr. Lincoln set me on a different path. Precision was his thing. My writing became like a series of algebra equations. My conclusions followed inexorably from the antecedent text, while giving a wide berth to any ground that might have been considered new or interesting. I continued this approach through my college study of philosophy, and it actually worked quite well.

If there has been any improvement since Choate, I think that performing music was probably a factor. Tone and rhythm are essential elements of flowing prose, and music woke me up to that. Getting the right note is only a starting point; getting the tone and articulation just right is what requires the fullest attention. And just as rehearsing music over and over moves one ever closer to something acceptable, writing allows for endless editing, my favorite delay tactic (greatly abetted by the rise of computerized word processing). Nothing I have ever written would survive another reading without yet a further attempt to make it crisper, more incisive, funnier.

If I didn’t subject myself to the discipline of unyielding deadlines, I would have long since suffocated amidst piles of unreleased drafts.

All this assumes that there is something to explain, and I am not so sure about that. All I can really say, for what it is worth, is that what comes out is just the inevitable result of who I am and all that has happened to me along the way.

And the head-first slide remains a part of that.

Tom Courage, of Providence, is a retired lawyer.

Home before dark

“Farmer’s Dog” (oil on canvas), by Gay Freeborn, in the group show “All Paths Home,’’ at the Lakes Gallery at Chi-Lin, Laconia, N.H., through Oct. 26

N.E. income gaps

The Gini score has been used to measure income dispersion for a century. A Gini score of one signifies that one household received 100 percent of the income in a region; zero signifies perfect equality of income distribution. The most recent U.S. score was 46.8. This is more uneven income distribution than in Europe, where most countries score between 25 and 35, and similar to Argentina or El Salvador, which score 46 and 47 respectively.

In New England, 62 of the 67 counties score below the United States average (signaling more-equal income dispersion). The region's population-weighted average is 45.2. The county scores range from a low of 38.2 (more equal incomes) to a high of 54.7 (most widely disparate incomes). In Franklin County, Vt. (Gini score of 38.2), the top 5 percent of households receive 16.6 percent of the aggregate income.

In Nantucket County, (Gini score of 54.7), the top 5 percent receive 34 percent of the aggregate income.

Franklin County, Vt., has the smallest gap between low-income and high-income residents. Nantucket County, has the biggest gap. Check the map for your county.

Via the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

Source: 2006-2010 American Community Survey, prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau, 2011. World Development Indicators, The World Bank 2012.

Into the blue

“Blue Leda Tondo” (encaustic on panel), by Martin Kline, in his show “The Art of Martin Kline,’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, Nov. 8-June 7.

Llewellyn King: Fear floods America under Trump

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is enough fear to go around.

There is fear of the indescribable horror when the ICE men and women, their faces hidden by masks, grab a suspected illegal immigrant. Their grab could come at the person's home or place of work, while picking up a child from school or standing in the hallway of a courthouse.

That person knows fear as never before. That person's life, for practical purposes, may be over: loved ones left behind, hope shredded. He or she may be shipped to a place where they won't be able to survive.

Fear is there because, maybe decades ago, they sought a better life and voted for it with their feet.

There is no time to argue, no time to ask why, no time to say goodbye. No time to prove your innocence or your U.S. citizenship. It is raw fear — the fear that secret police have always used.

There is the fear of those who work in government — once one of the securest jobs in the country — that they will be fired because their legitimate work in another administration is an affront to this one.

This hammer has come down in the Department of Justice, the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security and the Pentagon. The crime: supposedly being on the wrong side of history.

There is fear in the universities. Once a babel of free, even outrageous speech, they are cowed.

Mighty Harvard, one of the shiniest stars in the education firmament, is dulled, and other universities fear they will be next. Everywhere academics worry that what they say in their classrooms might be reported as inappropriate — their careers ended.

There is fear in the law firms. A new concept is at work: an advocate is somehow guilty because of whom they defended. This violates the whole underpinning of law and advocacy, dating back to Mesopotamia, ancient Greece and Rome, now asunder in the United States.

Media are afraid. Disney, CBS and The Washington Post have bent before the fear of retribution, the fear that other aspects of their business will pay the price for freedom of speech. Journalists fear the First Amendment is abridged and won't protect them.

There is fear, albeit of a lower order, across corporate America as it has become apparent that the government can reach deep down into almost any company, canceling contracts, withholding loan guarantees and, worse, ordering an “investigation." That is a punishment that costs untold dollars and shatters good names, even if no prosecution follows.

Elected officeholders have reason to feel fear. President Trump has suggested that Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker and Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson should be in jail. Is his compliant Department of Justice working on that? Fear is unleashed for the elected. Doing your job is no protection.

If you have expressed an opinion that could be judged as subversive, the state could come after you. Suppose you walk in a demonstration, exercising your constitutional right to assemble and petition? Suppose you wrote something on social media, so easily traced with AI, which is now out of step with the times? Satire? Opinion? News? Facts that are out of fashion? If you have posted, be afraid.

If you take a flight these days, the Transportation Security Administration will ask you to look into a camera. Then government has a fresh picture of you in its active system, ready for facial recognition software to identify you. It will ID you if you should be walking in a demonstration or just be near one. Your own picture, so easily captured by modern technology, can convict you.

What is the purpose of that picture? It has no bearing on the flight you are about to take. The same thing is true when you reenter the country from abroad. Smile for Big Brother.

Surveillance is a favored tool of the authoritarian state. I have seen it at work in Cuba, in apartheid South Africa and in the Soviet Union. Successive U.S. administrations have been quick to criticize the increasing use of technology for surveillance in China. No more.

Troops are being ordered into cities where the locals don't want them. They come under the promiscuous use of the Insurrection Act of 1807.

Does America fear insurrection? No, but there is fear of federal troops in our cities.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy consultant. He’s based in Rhode Island.

Let it loose

“Rewilding” (acrylic on canvas), by Marli Thibodeau, in her show at Gallery Sitka, Newport, R.I., opening Nov. 14.

Chris Powell: What next? A course in oppression?

At the University of Connecticut campus, in Storrs.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Thanks to President Trump, Connecticut now knows a little more about the politically correct nuttiness that afflicts the state's public higher education.

In response to the Trump administration's directive to colleges to get rid of “diversity, equity, and inclusion" stuff or risk losing federal funding, the University of Connecticut said the other day it is suspending a one-credit course on “anti-Black racism" -- a course that seems not to have gotten statewide publicity before.

The Hartford Courant reports that the University Senate voted in 2023 to make completion of the course a requirement for graduation but university administrators didn't get around to doing so. They hope to reinstate the course eventually somehow.

It's not that racism isn't an important subject in United States and world history. It's that separating a course on racism from the teaching of U.S. history and world history -- subjects of which most college students are largely ignorant -- is obviously an exercise in political correctness, guilt mongering, and inflicting a mentality of victimization and entitlement on minority students.

After all, how can one graduate from a high school in Connecticut without knowing that tribalism and racism are basic in history and that the history of the United States in particular is largely a matter of the long and sometimes bloody struggle to overcome them and expand democracy?

But then educational proficiency tests long have suggested that most Connecticut high-school graduates never master high school English and math. If they haven't mastered English, they haven't mastered history. Indeed, they may not even be able to spell it. So for many students a college course requirement in anti-Black racism is probably crowding out basic learning.

The Courant also reports that when the University Senate approved the anti-Black racism course it envisioned adding similar courses about the mistreatment of other groups -- people with darker complexions, Jews, Asians, Muslims, and members of sexual minorities. So maybe, if not for Trump, in another year or two UConn might be offering not just a course in anti-Black racism but entire undergraduate, master's, and doctoral degrees in oppression suffered in the United States, even as the country has been overwhelmed by millions of immigrants who somehow see refuge and opportunity here.

Nowhere has what used to be called the ascent of man been hastened more than in the United States. Land-grant institutions of higher education such as UConn have been a big part of that ascent.

Students admitted to UConn today are amazingly diverse in race, ethnicity, and other backgrounds and are among the luckiest people in the world. UConn should stop using political correctness to turn them into victims.

xxx

Connecticut's ascent was not accomplished by giving the store away as state government long has been doing, a practice exposed again lately by one of the Yankee Institute's journalists, Meghan Portfolio.

Last month Portfolio detailed the case of Shellye Davis, who is nominally a paraeducator in the Hartford school system -- you know, the system that happily advances illiterates and gives them high school diplomas. Davis is president of the Hartford Federation of Paraeducators and secretary-treasurer of the Connecticut AFL-CIO, and Portfolio reported that she doesn't show up for work much even though she is paid as if she does.

Davis was absent from work with pay for 152 days in less than three years -- 55 sick days, 38 “professional development" days, 33 union leave days, and 26 personal days. Some of these days were spent lobbying the General Assembly and participating in political events.

Extreme paid absences like those of Davis are actually authorized for union leaders by the Hartford school system's contract with its unions. State government has a similar practice. In Connecticut the public pays many government employees not to do the jobs they were hired for but instead to work politically against the public interest.

Given their dismal performance, how can Hartford's schools afford to spend money this way? It's probably easier when you don't really care much about education.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

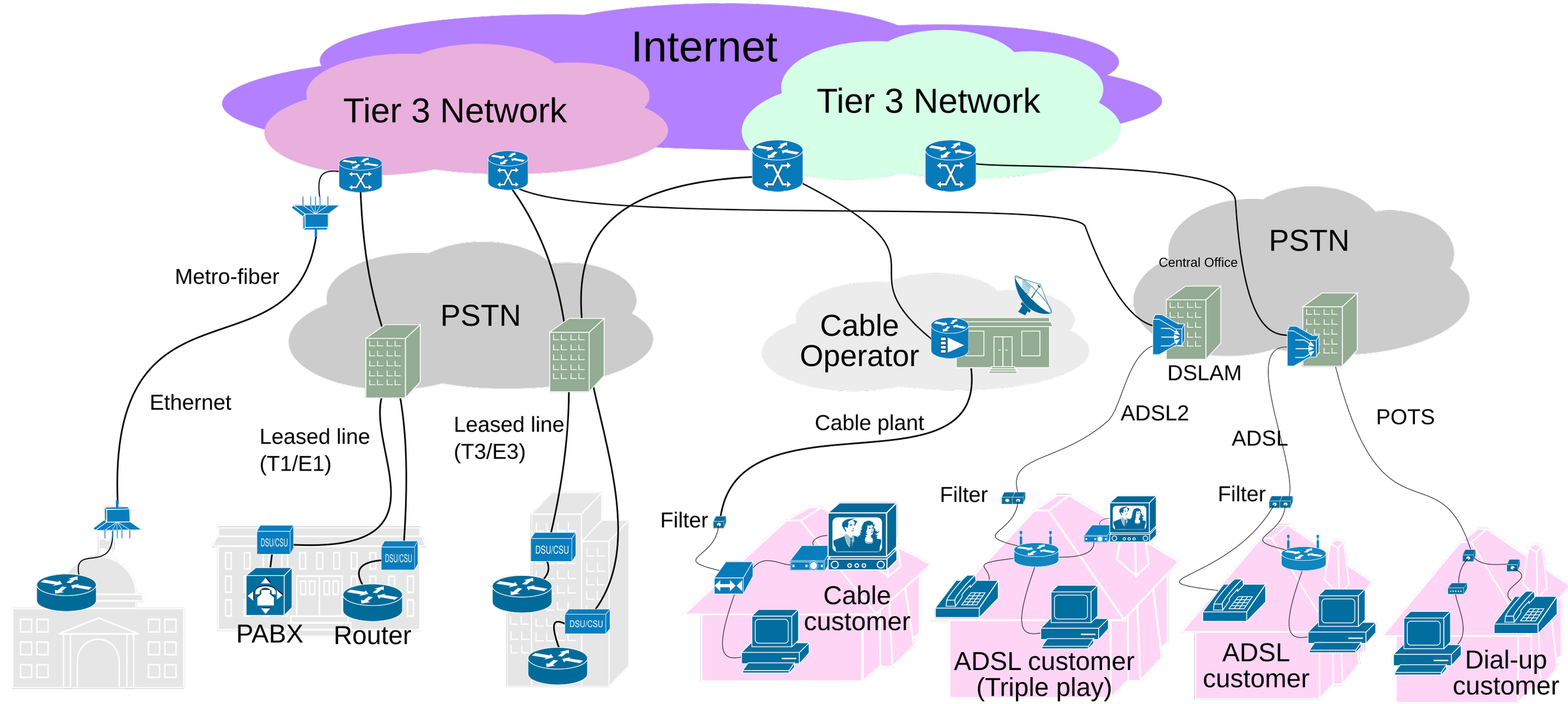

Sarah Jane Tribble: Trump has acted to kill Digital Equity Act

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News, except for images above

“The Internet provides this extra layer of resilience.”

— Christina Filipovic, who leads the research for an initiative of the Institute for Business in the Global Context at Tufts University, in Medford, Mass.

Megan Waiters can recite the stories of dozens of people she has helped connect to the Internet in western Alabama. A 7-year-old who couldn’t do classwork online without a tablet, and the 91-year-old she taught to check health-care portals on a smartphone.

Dead Zone

Millions of rural Americans live in counties with doctor shortages and where high-speed Internet connections aren’t adequate to access advanced telehealth services.

A KFF Health News analysis found people in these “dead zones” live sicker and die younger on average than their peers in well-connected regions.

“They have health-care needs, but they don’t have the digital skills,” said Waiters, who is a digital navigator for an Alabama nonprofit. Her work has involved giving away computers and tablets while also teaching classes on how to use the internet for work and personal needs, like banking and health. “It’s like a foreign space.”

Those stories are now bittersweet.

Waiters is part of a network of digital navigators across the country whose work to bring others into the digital world was, at least in part, propped up by a $2.75 billion federal program that abruptly canceled funding this spring. The halt came after President Trump posted on his Truth Social platform that the Digital Equity Act was unconstitutional and pledged “no more woke handouts based on race!”

The act lists exactly whom the money should benefit, including low-income households, older residents, some incarcerated people, rural Americans, veterans, and members of racial or ethnic minority groups.

Politicians, researchers, librarians, and advocates said defunding the program, along with other changes in federal broadband initiatives, jeopardizes efforts to help rural and underserved residents participate in the modern economy and lead healthier lives.

“You could see lives change,” said Sam Helmick, president of the American Library Association, recalling how they helped grandpas in Iowa check prescriptions online or laid-off factory workers fill out job applications.

The Digital Equity Act is part of the sweeping 2021 infrastructure law, which included $65 billion to build high-speed Internet infrastructure and connect millions without access to the internet.

This year, Congress once again pushed for a modern approach to help Americans, mandating that state leaders prioritize new and emerging technologies through its $50 billion Rural Health Transformation Program.

A KFF Health News analysis found that nearly 3 million people in America live in areas with shortages of medical professionals and where modern telehealth services are often inaccessible because of poor internet connections. The analysis found that in about 200 mostly rural counties where dead zones persist, residents live sicker and die earlier on average than people in the rest of the country. Access to high-speed internet is among a host of social factors, like food and safe housing, that help people lead healthier lives.

“The Internet provides this extra layer of resilience,” said Christina Filipovic, who leads the research for an initiative of the Institute for Business in the Global Context at Tufts University. The research group found in 2022 that access to high-speed internet correlated with fewer covid deaths, particularly in metro areas.

During the covid-19 pandemic, federal lawmakers launched a subsidy program paid for by the infrastructure law. That aid, called the Affordable Connectivity Program, aimed to connect more people to their jobs, schools, and doctors. In 2024, Congress did not renew funding for the subsidy program, which had enrolled about 23 million low-income households.

This year, U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick revamped and delayed the infrastructure law’s construction initiative — known as the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program, or BEAD — after announcing plans to reduce regulatory burdens.

More than 40 states and territories have submitted final proposals to extend high-speed Internet to underserved areas under the administration’s new guidelines, according to a Commerce Department dashboard.

In May, the Digital Equity Act’s funding was terminated within days of Trump’s Truth Social post.

While many states in 2022 had received money to plan their programs, the next round of funding, designated for states and agencies to implement the plans, had largely been awarded but not distributed.

Instead, federal regulators — including the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, the federal agency overseeing implementation of the Digital Equity Act — notified recipients that the grants would be terminated. The grants were created and administered with “unconstitutional racial preferences,” according to the letter.

In Phoenix, officials learned in January that the city was slated to get $11.8 million to increase Internet access and teach digital literacy, but they received an email May 20 stating that all grants, “except for grants to Native Entities,” had been terminated.

“It’s a shame,” said Phoenix Mayor Kate Gallego, a Democrat. The money, she said, would have helped 37,000 residents get Internet access.

Georgia’s Democratic leaders in July sent a letter to Lutnick and NTIA’s then-acting administrator, Adam Cassady, urging reinstatement of the money, noting that the federal cut ignores congressional intent and violates public trust.

The act’s creator, Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), said during an online press conference in May that Republican governors in 2024 supported the law and its funding when each state touted completing its required digital equity plans and asked for resources.

“I cannot believe there aren’t Republican governors out there that are going to join with us to fight back on this,” Murray said, adding “the other way is through courts.”

All 50 states developed digital equity plans after months of focus groups, surveys, and public comment periods. NTIA Digital Equity Director Angela Thi Bennett, during an August 2024 interview with KFF Health News, said the “intentional community engagement” by federal and state leaders to deliver broadband to unserved communities was “the greatest demonstration of participatory democracy our country has ever seen.”

Thi Bennett could not be reached for comment on this article. NTIA spokesperson Stephen Yusko said the agency “will not be able to accommodate” a request for an interview with Thi Bennett and did not respond to questions for this article.

Caroline Stratton, a research director at the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society, said the act’s funding allowed states to staff offices; identify existing high-speed Internet programs, including those operating within other state agencies; and create plans to fill the gaps.

“This sent folks out looking,” Stratton said, to see whether agencies in the state were already working on health-improvement plans and to ask whether the broadband work could contribute and “actively help move the needle.”

State grant applications included goals to promote health care access. In Mississippi, the plan consists of the state university and another agency’s health improvement plan, Stratton said.

While states were required to create programs that would help specific covered populations, some states modified the language or added subcategories to include other populations. Colorado’s plan included immigrants and “individuals experiencing homelessness.”

“In every state, there’s a loss,” said Angela Siefer, executive director of the National Digital Inclusion Alliance. The nonprofit, which was awarded nearly $26 million to work with organizations nationwide but did not receive any funds, filed a lawsuit Oct. 7 seeking to force Trump and the administration to distribute the money.

“The digital divide is not over,” Siefer said.

The nonprofit’s grant had been planned to support digital navigators in 11 states and territories, including Waiters. Her employer, the nonprofit Community Service Programs of West Alabama, expected to receive a $1.4 million grant.

In the past two years, Waiters spent hours driving the roads of rural Alabama to reach residents. She has distributed 648 devices — laptops, tablets, and SIM cards — and helped hundreds of clients through 117 two-hour digital skills classes at libraries, senior centers, and workplace development programs in and around Tuscaloosa, Ala.

People of “all races, of all ages, of all financial backgrounds” who did not “fit into our typical minority category” were helped through her work, Waiters said. Trump and his administration should know, she said, “what it actually looks like for the people I serve.”

Sarah Jane Tribble is a KFF reporter: sjtribble@kff.org, @sjtribble

We’re all entangled

“Hassocky Meadow Trail, Ipswich River Wildlife Sanctuary,’’ in spring 2024, in Mary Lang’s show “Entangled,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Nov. 2

She says:

“For decades my photographs had offered a feeling of space, often of groundlessness, of vast sky or open water, or at least an expansive horizon. Now, I am drawn to photograph tangled trees, vines, almost impenetrable thickets of growth. Why? What am I looking at? What am I trying to see? Or describe? This exhibition is the beginning of my answer to that question.

“First, these images are an invitation to take in complexity, to not feel claustrophobic when confronted by layers of growth, of living things, of pathless thickets, of entangled vines and branches. They are an invitation to be awed and drawn to more detail than your mind can absorb. In this fraught world, we need to increase our capacity to handle complexity. Secondly, they are a metaphor for entanglement, a term ecologists and climate activists use to describe the complexity of modernity: everything we do, everything that all of us do, everything that the earth does, is completely entangled, interdependent, inseparable. As human beings living in the Anthropocene era, we can’t avoid our complicity in the harm to the planet.’’

John Whipple House, in Ipswich, was built in 1677.

‘Light, hope, and joy’

“Radiant” (encaustic), by Marcia Crumley, in her show, “Finding Joy,’’ at Blue Door Gallery, York, Maine, through Nov. 9.

The gallery says Crumley’s work “captures the emotional and visual beauty of the natural world. This vibrant collection reflects not only her personal journey through painting, but our shared pursuit of light, hope, and joy in uncertain times. Expect a luminous mix of night skies, seascapes, and color-saturated landscapes that celebrate the everyday wonder around us.’’

Sewall’s 1794 map of York

Aaron Mansfield: Of football fandom and physical health

From The Conversation, except for picture above.

NORTH ANDOVER, Mass.

Aaron Mansfield is an assistant professor of sport management at Merrimack College.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Being from Buffalo means getting to eat some of the best wings in the world. It means scraping snow and ice off your car in frigid mornings. And it means making a lifelong vow to the city’s NFL franchise, the Bills – for better or worse, till death do us part.

When I grew up in New York’s second-largest city, my community was bound together by loyalty to a football team that always found new ways to break our hearts.

And yet at the start of each NFL season, we always found reasons to hope – we couldn’t help ourselves.

Coming from this football-crazed culture, I often wondered about the psychology of fandom. This eventually led me to pursue a Ph.D. in sport consumer behavior. As a doctoral student, I was most interested in one question: Is fandom good for us?

I found a huge body of research on the psychological and social effects of fandom, and it certainly made being devoted to a team look good. Fandom builds belonging, helps adults make friends, boosts happiness and even provides a buffer against traumatic life events.

So, fandom is great, right?

As famed football commentator Lee Corso would say: “Not so fast, my friend.”

While fandom appears to be a boon for our mental health, strikingly little research had been conducted on the relationship between fandom and physical health.

So I decided to conduct a series of studies – mainly of people in Western countries – on this topic. I found that being a sports fan can have some drawbacks for physical health, especially among the most committed fans.

Reach for the nachos

Playing sports is healthy. But watching them? Not so much.

Tailgating culture revolves around alcohol. Research shows that college sports fans binge drink at significantly higher rates than nonfans, are more likely to do something they later regretted and are more likely to drive drunk. Meanwhile, watch parties encourage being stationary for hours and mindlessly snacking. And, of course, fandom goes hand in hand with heavily processed foods like wings, nachos, pizza and hot dogs.

One fan told me that when watching games, his relationship with food is “almost Pavlovian”; he craves “decadent” foods the same way he seeks out popcorn at the movies.

Inside the stadium, healthy options have traditionally been scarce and overpriced. A Sports Illustrated writer joked in 1966 that fans leave stadiums and arenas with “the same body chemistry as a jelly doughnut.”

Little seems to have changed since. One Gen Z fan I recently interviewed griped, “You might find one salad with a plain piece of lettuce and a quarter of a tomato.”

Eating away anxiety and pain

The relationship between fandom and physical health isn’t just about guzzling beer, sitting for hours on end or scarfing down hot dogs.

One study analyzed sales from grocery stores. The researchers found that fans consume more calories – and less healthy food – on the day following a loss by their favorite team, a reaction the researchers tied to stress and disappointment.

My colleagues and I found something similar: Fandom induces what’s called “emotional eating.”

Emotions like anger, sadness and disappointment lead to stronger cravings. And this relationship is tied to how your favorite team performs when it matters most. For example, we found that games between rivals and closely contested games yield more pronounced effects. Emotional states generated by the game are also significantly correlated with increased beer sales in the stadium.

High-calorie cultures

In another paper, my co-authors and I found that fans often feel torn between their desire to make healthy choices and their commitment to being a “true fan.”

Every fan base develops its own culture. These unwritten rules vary from team to team, and they aren’t just about wearing a cheesehead hat or waving a Terrible Towel. They also include expectations around drinking, eating and lifestyle.

These health-related norms are shaped by a variety of factors, including the region’s culture, team history and even team sponsorships.

For example, the Cincinnati Bengals partner with Skyline Chili, a regional chain that makes a meat sauce that’s often poured over hot dogs or spaghetti. One Bengals fan I interviewed observed that if you attend a Bengals game, sure, you could eat something else – but a “true fan” eats Skyline.

I have two studies in progress that show how hardcore fans typically align their health behaviors with the health norms of their fan base. This becomes a way to signal their allegiance to the team, improve their standing among fellow fans, and contribute to what makes the fan base distinct in the eyes of its members.

In Buffalo, for example, tailgating often revolves around alcohol – so much so that Bills fans have a reputation for over-the-top drinking rituals.

And in New Orleans, Saints fans often link fandom to Louisiana food traditions. As one fan explained: “People make a bunch of fried food or huge pots of gumbo or étouffée, and eat all day – from hours before the game until hours after.”

New generation of health-conscious fans

The fan experience is shaped by the culture in which it is embedded. Teams actively help shape these cultures, and there’s a business argument to be had for teams to play a bigger role in changing some of these norms.

Gen Z is strikingly health-conscious. They’re also less engaged with traditional fandom.

If stadiums and tailgates continue to revolve around beer and nachos, why would a generation attuned to fitness influencers and “fitspiration” buy in? To reach this market, I think the sports industry will need to promote its professional sports teams in new ways.

Some teams are already doing so. The British soccer team Liverpool has partnered with the exercise equipment company Peloton. Another club, Manchester City, has teamed up with a nonalcoholic beer brand as the official sponsor of its practice uniforms.

And several European soccer clubs have even joined a “Healthy Stadia” movement, revamping in-stadium food options and encouraging fans to walk and bike to the stadium.

For the record, I don’t think the solution is replacing typical fan foods with smoothies and salads. Alienating core consumers is generally not a sound business strategy.

I think it’s reasonable, however, to suggest sports teams might add more healthy options and carefully evaluate the signals they send through sponsorships.

As one fan I recently interviewed said: “The NFL has had half-assed efforts like Play 60” – a campaign encouraging kids to get at least 60 minutes of physical activity per day – “while also making a ton of money from beer, food and, back in the day, cigarette advertisements. How can sports leagues seriously expect people to be healthier if they promote unhealthy behaviors?”

Today’s consumers want to support brands that reflect their values. This is particularly true for Gen Zers, many of whom are savvy enough to see through hollow campaigns and quick to reject hypocrisy. In the long run, I think this type of dissonance – sandwiching a Play 60 commercial between ads for Uber Eats and Anheuser-Busch – will prove counterproductive.

I, as much as anyone else, understand what makes fandom special – and yes, I’ve eaten my share of wings during Bills games. But public health is a pressing concern, and though the sports industry is well-positioned to address this issue, fandom isn’t helping. Actually, my research suggests it’s having the opposite effect.

Striking the balance I’m advocating will be tricky, but the sports industry is filled with bright problem-solvers. In the film “Moneyball,” Brad Pitt’s character, Billy Beane, famously says sports teams must “adapt or die.” He was referring to the need for baseball teams to integrate analytics into their decision-making.

Professional sports teams eventually got that message. Maybe they’ll get this one, too.

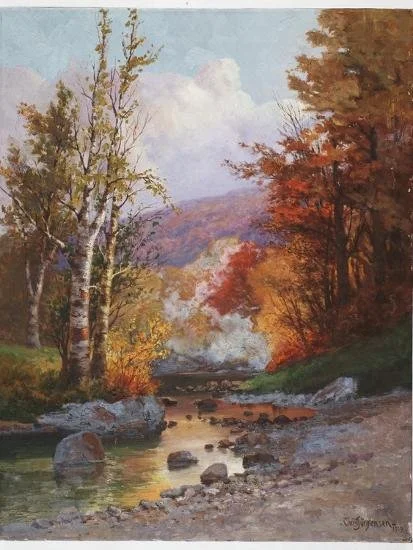

‘Why so soon’

“Autumn in The Berkshires” (circa 1919), by Christian Jorgensen.

Ere, in the northern gale,

The summer tresses of the trees are gone,

The woods of Autumn, all around our vale,

Have put their glory on.

The mountains that infold,

In their wide sweep, the coloured landscape round,

Seem groups of giant kings, in purple and gold,

That guard the enchanted ground.

I roam the woods that crown

The upland, where the mingled splendours glow,

Where the gay company of trees look down

On the green fields below.

My steps are not alone

In these bright walks; the sweet south-west, at play,

Flies, rustling, where the painted leaves are strown

Along the winding way.

And far in heaven, the while,

The sun, that sends that gale to wander here,

Pours out on the fair earth his quiet smile,--

The sweetest of the year.

Where now the solemn shade,

Verdure and gloom where many branches meet;

So grateful, when the noon of summer made

The valleys sick with heat?

Let in through all the trees

Come the strange rays; the forest depths are bright?

Their sunny-coloured foliage, in the breeze,

Twinkles, like beams of light.

The rivulet, late unseen,

Where bickering through the shrubs its waters run,

Shines with the image of its golden screen,

And glimmerings of the sun.

But 'neath yon crimson tree,

Lover to listening maid might breathe his flame,

Nor mark, within its roseate canopy,

Her blush of maiden shame.

Oh, Autumn! why so soon

Depart the hues that make thy forests glad;

Thy gentle wind and thy fair sunny noon,

And leave thee wild and sad!

Ah! 'twere a lot too blessed

For ever in thy coloured shades to stray;

Amid the kisses of the soft south-west

To rove and dream for aye;

And leave the vain low strife

That makes men mad--the tug for wealth and power,

The passions and the cares that wither life,

And waste its little hour.

— “Autumn Woods,’’ by William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878), American poet, essayist and editor. He grew up in Cummington, Mass., just east of The Berkshires.

A matter of priorities

ECHO, Leahy Center for Lake Champlain, in Burlington.

Photo by Mfwills

“If the environment were a bank, it would have been saved by now.’’

— Bernie Sanders, U.S. senator from Vermont and a former mayor of Burlington

Drama queen

“Vaneeta,’’ from the show “Little Dramas,’’ by B. Lynch, at Danforth Art Museum, Framingham, Mass., through Jan. 11.

Mass. looks to the sun

In Massachusetts, solar installation at Newton North High School

ArnoldReinhold photo

Sun in the Bay State

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey is quite right to say that generating much more solar energy, and storing it with improved batteries, is the fastest and most efficient way to address the state’s increasing energy needs. That’s especially given such gargantuan electricity consumers as more data centers, especially for artificial intelligence, come online.

Indeed, local-and-state-overseen solar energy not vulnerable to shifting federal policies/politics is becoming ever more needed in the state. That’s partly because Washington’s current rulers dislike any energy not produced by burning oil, gas and coal. (The fossil-fuel folks, based in Red States, are big Republican campaign donors.) And Trump particularly hates offshore wind projects, which he has been halting despite the billions of dollars that have been spent on them so far. Massachusetts officials had hoped that those turbines would meet much of the state’s electricity needs in the next few years.

So Ms. Healey’s administration has filed emergency regulations for the Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target (SMART) program to try to lower installation costs, speed up permitting and expand interconnections for solar.

The governor noted:

“Solar energy in Massachusetts, on the hottest single day of summer this year — behind-the-meter solar, which is the solar on our roofs and farms and schools — met 22 percent of statewide demand.’’ Data indicate that solar accounted for almost 27 percent of the state's electricity supply as of late 2024, up from 19 percent in 2020. It’s a very good thing it’s rising so fast: ISO New England, the region’s grid operator, predicts that power demand in New England will rise 11 percent by 2034.

But there can be big siting issues for solar farms, as opposed to rooftop installations. Cutting down trees should be avoided! Trees, by absorbing CO2 produced by fossil-fuel burning, obviously slow global warming.

Vacant developed land (such as parking areas of dead stores and malls) and roadside and median strips are good places for solar. If such facilities must be put in countryside fields, then grow plants below them. The plants of course absorb carbon dioxide. In a few farms, goats and sheep graze below high-mount solar-panel platforms. Farmers get some added revenue from selling the power to utilities.

Time is of the essence. Federal tax credits for nonresidential renewable-energy projects will expire at the end of 2027, and residential tax credits for renewable energy (which includes wind turbines but mostly involves rooftop solar) will shut off at the end of this year.

Much of the rest of the world is moving to renewable energy considerably faster than America as “green energy’’ installation cost declines and worry about global warming and pollution rises.

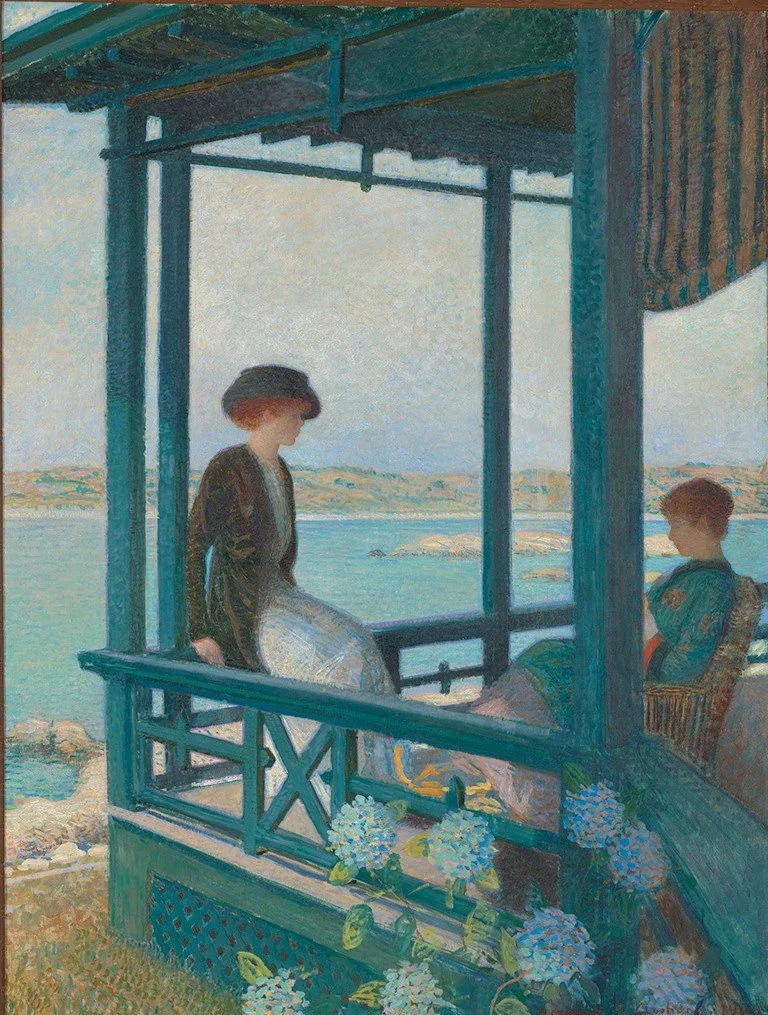

Big Oct. 23 event at the Newport Art Museum

“On the Veranda (The Blue Porch)’’ (1909 oil on canvas), by Howard Gardiner Cushing, in the show “Howard Gardiner Cushing: A Harmony of Line and Color,’’ through Dec. 31, at the Newport Art Museum. See this event.

Exploring presence and absence

“Grace Looking Through Hole in Log” (archival pigment print), by Scott Offen, in the show “Grace by Scott Offen,’’ at Panopticon Gallery, Boston, through Dec. 2.

The gallery says:

“The show, coinciding with the launch of Offen’s monograph with L’Artiere Edizioni, the exhibition features intimate, dreamlike portraits performed and co-created by his wife, Grace. Exploring collaboration, identity, and connection with nature, the work invites reflection on presence and absence.’’