'Depth and nostalgia'

”Field in Green’’ (oil on canvas) by Hannah Bureau’ in her show “Intersect,’’ opening in November at Edgewater Gallery, Boston. The gallery explains:

“Hannah Bureau's paintings lie at the intersection of landscape and abstraction. She is interested in creating space and distance that feels like the familiar world around us but is ambiguous, general, and abstracted. In Bureau's painted world she establishes visual plains and geometric shapes that intersect, overlap, pile-up, and ultimately create a sense of visual distance, depth and nostalgia.’’

Jill Richardson: California fires show why we need publicly owned utilities

Satellite view of Kincade Fire smoke in northern California on Oct. 24

Via OtherWords.org

Hundreds of thousands of Californians have been fleeing raging wildfires, while millions sit in the dark. And for-profit utilities may be to blame.

Pacific Gas & Electric — a private, for-profit utility in the state — has admitted that its equipment likely caused 10 wildfires this year alone. To avoid further damage, the utility has been shutting off its customers’ power when weather conditions cause increased fire danger.

Will this lower the risk of wildfires? Maybe. It will also leave blacked out hospitals choosing whether to refrigerate their vaccines or keep their medical records online.

As Vox environmental reporter David Roberts put it, giving customers a choice between blackouts or fires is a failure.

A popular theory says that businesses must be “efficient” in order to survive in a competitive marketplace. By contrast, the government — without such market pressure — is naturally “inefficient.”

But even in the best cases, for-profit utilities with state-sanctioned monopolies are not functioning in a competitive marketplace. And unlike public utilities, which simply have to cover the costs of operating, privatized utilities must generate something else: profits.

How do they do this? By cutting costs — including employee salaries and benefits, customer services, and equipment upgrades. In the case of PG&E, it’s meant failing to upgrade and maintain their aging infrastructure.

It would be one thing if PG&E’s grid used all of the latest, most up-to-date technology. But that’s not the case. Instead of making their grid more resilient, now they simply shut it off when the weather gets bad — and it may still be causing fires.

And if customers don’t like that, too bad. It’s a monopoly.

Prices and service aren’t the only things at stake. We also need to get power from sources that are reliable, safe, and environmentally clean.

A corporation with a profit incentive, which needs to provide shareholders with growth each quarter, may not invest in that. Upgrading and maintaining infrastructure cuts into profits, giving them a reason to sacrifice safety and eco-friendliness to cut costs.

Imagine a circumstance in which most consumers and businesses get their power from clean, rooftop solar panels.

Sounds great, but there’s a big problem for for-profit utilities: After the initial manufacturing and installation, there’s no profit in people getting their power from the sun.

It’s clean, it’s technologically sound, and yet it’s not available to most people. As long as private, for-profit corporations provide our power, cleaner solutions like rooftop solar will remain out of reach to many.

But what if we had publicly owned utilities?

The wildfires — and the climate crisis that’s making them worse — are public problems. The reliability of our power grid is a public need.

When we privatize our utilities, we limit the solutions we can choose from to those that are profitable to a corporation. We risk situations like the one we are in now, in which the public is suffering the consequences of decisions a private entity made to maximize its own profits.

The public interest, not private profit, should be priority No. 1. If there’s a silver lining to this mess with PG&E, it’s that more people will demand that

Jill Richardson, a sociologist, is a columnist for OtherWords.org.

Chris Powell: Stupidity and hypocrisy exceed racism at UConn

Main quad at the University of Connecticut’s flagship campus, in Storrs

Funny what gets people upset and what doesn't get them upset at the University of Connecticut these days.

A great scandal was contrived lately when two white students got drunk at a bar one night and, walking home across campus, played a game of shouting vulgar words to no one in particular. The vulgarities eventually included a racial slur that was heard by two people in a nearby apartment.

So scores of students marched and rallied in protest as if this disgraceful juvenility was not only a war crime but also representative of white students and university policy generally. Predictably cowed, the university's new president accused the two white drunks of doing "egregious harm." The two were tracked down and arrested on a charge of ...ridicule. They confessed and apologized.

Meanwhile, a member of the university's men's basketball team got drunk at a party, stole a car, sped off, crashed into a street sign and another car, and, when stopped by a police officer, smelled of liquor and ran away. He was tracked down and was charged with evading responsibility, interfering with an officer, driving too fast, and driving without a license. He, too, confessed and apologized. The woman whose car he stole decided not to complain.

But though the basketball player had damaged property and put lives at risk, no university official accused him of causing "egregious harm" and there were no protests and rallies about his misconduct. Instead his coach made excuses for him. He's black.

Yes, there may be some racism at UConn, as everywhere, but mostly there are stupidity, hypocrisy, and political correctness, and they afflict cowardly university administrators as much as politically opportunistic students.

xxx

Connecticut state government's primary purpose was revealed the other day by a Yankee Institute study of the gross insolvency of the state teacher pension system. The study reported that 22 percent of state revenue is used for funding pensions and medical insurance for retired state employees and municipal teachers, and that fully funding the pension and insurance systems would consume 35 percent.

The study recommended easing the teacher pension burden by encouraging private schools, whose staffs are paid less. But doing that would barely be noticed amid the deep hole into which Connecticut has fallen with its capitulation to the government employee unions.

Connecticut will be able to resume normal state government -- government whose purpose is serving the public, not its own employees -- only when it gets out of the pension business entirely, outlawing state-provided defined-benefit pensions and medical insurance for state and municipal government retirees. Even that remedy will take decades to produce results, since it could start only with new hires.

xxx

A spokeswoman for Connecticut Atty. Gen. William Tong confirmed last week that the attorney general will not intervene with antitrust law against the merger of People's United Bank and United Bank, whose operations overlap heavily. The attorney general concluded that the merger would not reduce competition enough to harm depositors or borrowers.

But competition levels provide lots of discretion for antitrust authorities, and the merger is likely to eliminate hundreds of jobs.

Oh, well -- at least the attorney general last week also appealed to the U.S. Department of Energy not to weaken energy-efficiency rules for dishwashers.

xxx

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Women and GOP governors

Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

A recent poll showed that four of the 10 most unpopular governors are women, with Ms. Raimondo (who is very charming in person) the most disliked. How much of this is sexism, which played a role in Hillary Clinton’s loss in 2016, with its rhetoric of “that bitch,’’ etc.? Meanwhile, the two most popular governors are Massachusetts’s Charlie Baker and Maryland’s Larry Hogan, both Republicans in liberal states and known for their competence and integrity – all of which means that, unlike 50 years ago, they would not be qualified now to be GOP presidential candidates. Besides Mr. Baker, New England has two other very able GOP governors – Vermont’s Phil Scott (whom I’ve met) and New Hampshire’s Chris Sununu.

Many of the Republicans in Congress don’t actually do anything substantive (such as crafting legislation). They spend much of their time going on the likes of Fox “News’’ and denouncing such cooked up bogus ogres as the “Deep State’’ (meaning patriotic and often physically brave government officials, including diplomats, CIA officials and military officers, who might push back against the treason and other corruption of the Trump mob). And of course, as with most of their Democratic colleagues, they spend much of their time raising money from, and trying to please, their big donors – an activity that has intensified with the treasure trove of political money unleashed by the Citizens United Supreme Court ruling, in 2010 – one of the greatest producers of political corruption in American history.

But governors, for their part, have to actually govern in a real, fact-based world. The Republican Party on Capitol Hill is a cesspool of corruption. If there is a future for thoughtful center-right Republicanism it must come from the governors.

'Back to ourselves'

At Lincolnville, Maine’s centennial

Narcissus, by Caravaggio

“We thought that the Internet was going to connect us all together. As a young geek in rural Maine, I got excited about the Internet because it seemed that I could be connected to the world. What it's looking like increasingly is that the Web is connecting us back to ourselves.’’

Eli Pariser, the chief executive of Upworthy, a Web site for "meaningful" viral content. He hails from Lincolnville, Maine.

Lincolnville Beach in high summer

‘Fall falling on us’

— Photo by TomwoodO

“Suddenly feel something invisible and weightless

Touching our shoulders, sweeping down from the air:

It is the autumn wind pressing against our bodies;

It is the changing light of fall falling on us.’’

From “Fall,’’ by Edward Hirsch

70 years of arts patronage

— Photo Courtesy of Tom Grotta

Work by Norma Minkowitz (top) and Mary Giles (bottom) in the show “Artists From the Grotta Collection,’’ at browngrotta arts, Wilton, Conn., Nov. 3-10 and open 10 a.m..-5 p.m.. daily. The show features important works of fiber and dimensional art, by more than 40 artists, collected by Sandy and Louis Grotta.

browngrotta arts explains: “Long-time patrons of the Museum of Arts and Design and the American Craft Museum of New York the Grottas’ collection represents 70 years of arts patronage as well as unique friendships fostered by the Grottas with pioneering contemporary craft makers in textile art, sculpture, furniture and jewelry.’’

J. Alden Weir’s studio at the Weir Farm National Historic Site, in Ridgefield and Wilton, Conn. The park honors the life and work of American impressionist painter J. Alden Weir and other artists who visited or lived there, including Childe Hassam, Albert Pinkham Ryder, John Singer Sargent and John Twachtman.

Weir Farm is one of two sites in the National Park Service devoted to the visual arts, along with Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, in Cornish, N.H., named for the famous sculptor.

e pluribus unum

“One Legged Table,’’ by Mags Harries, at Boston Sculptors Gallery, Nov. 6-Dec. 8. The gallery reports: “Tackling themes ranging from global warming to the survival of humankind, Mags Harries's new solo exhibition will feature a reprise of her 2008 piece the “One Legged Table’’. The table, a symbol of community gathering and a place to plan action, is composed of parts from 13 different kitchen and dining tables. Each section is supported by just one leg, which when joined together create one large unified structure.’’

Tackling themes ranging from global warming to the survival of humankind, Mags Harries' new solo exhibition will feature a reprise of her 2008 piece the One Legged Table. The table, a symbol of community gathering and a place to plan action, is comprised of parts from thirteen different kitchen and dining tables. Each section is supported by just one leg, which when joined together create one large unified structure.

Harries' One Legged Table will serve as a site for discussion and action. During the run of the show, a series of brunches will be held addressing topics relevant to climate change. The invitees, each specializing in diverse disciplines, will come together in the gallery to create an action generated from their discussion. A series of thirteen iceberg sculptures, cast in metal and resin, will be shown alongside the One Legged

Table.

TR great-grandson to discuss president's legacy

Official White House portrait of Theodore Roosevelt, by the famed painter John Singer Sargent, who spent most of his life in Europe but came from an old New England family.

To members and friends of the Providence Committee on Foreign Relations (thepcfr.org; pcfremail@gmail.com):

Tweed Roosevelt, president of the Theodore Roosevelt Association and great-grandson of that president, will be our dinner speaker on Wednesday, Nov. 6. He’ll talk about how TR’s foreign policy, which was developed as the U.S. became truly a world power, affected subsequent presidents’ foreign policies.

In 1992, Mr. Roosevelt rafted down the 1,000-mile Rio Roosevelt in Brazil—a river previously explored by his great-grandfather in 1914 in the Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific Expedition and then called the Rio da Duvida, the River of Doubt. The former president almost died on that legendary and dangerous trip.

After graduation from Harvard, Mr. Roosevelt served for two years as a VISTA volunteer in Harlem, Bedford Stuyvesant, and the Lower East Side of New York City and went on to NYC’s Human Resources Administration. He subsequently earned his MBA and then taught for two years at Columbia University. A long career in management consulting and finance culminated in his becoming Chairman of Roosevelt China Investments, which, among other businesses, owns and operates the House of Roosevelt on Shanghai’s Bund.

Over the years, Mr. Roosevelt has done much to further the memory and ideals of Theodore Roosevelt. He has lectured and taught about TR at numerous institutions and schools around the world, including Harvard, Marshall, and Santa Clara Universities, ranging from single lectures to a 20-hour course that involved as guest speakers most of the well-known historians of TR.

He has also lectured on a wide range of other subjects, including conservation and the environment, hunting, politics, literature, history, mathematics, Japanese-American relations, and exploration, and has retraced many of TR’s adventures in the American West, Africa, and the Amazon. He has appeared on numerous television documentaries and radio programs and was awarded the prestigious Telly Award for his public service announcement on presidential log cabins.

Schedule:

6:00 - 6:30 PM: Cocktails

6:30 - 7:30: Dinner (salad, entree, dessert/coffee)

7:30 - 8:30: Speaker Presentation

8:30 - 9:00: Q&A with Speaker.

For information on the PCFR, including on how to join, please see our Web site – thepcfr.org – or email pcfremail@gmail.com or call 401-523-3957

Maybe go into another business?

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘Maybe the owners of the gigantic and mega-glitzy Encore Boston Harbor casino, in the formerly industrial city of Everett, should get out of the saturated southern New England casino racket and stick to the bus and boat business. Instead of the originally projected $1 billion revenue for 2019, Encore appears headed for only $600 million. They must be praying there won’t be any big snow and ice storms between now and the end of the year. I wonder what will happen in the next recession. Maybe it will be good for casinos because suckers will become that much more desperate for a quick killing.

To drum up its business by waving the banners of bonanzas to cure their customers’ financial anxieties, Encore is now offering free parking, free bus trips to the palace on the Mystic River waterfront and very cheap boat travel. Its boat service is heartening – the more commuter boats the better on Boston Harbor.

xxx

With the long and confusing war between IGT and Twin River over the Rhode Island gambling business, one almost wants the state to get rid of these middlemen and go directly into the casino business itself, sort of like the liquor stores owned and operated by some states. Reduce the layers of corruption and cut operating costs!

Grace Kelly: Reef balls deposited to lure sport fish

Reef balls being dropped into an area to lure fish in the Gulf of Mexico

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

EAST PROVIDENCE, R.I.

The mayor, a slew of media members, and a group of residents celebrating a birthday — complete with cake and party hats — gathered Oct. 24 at Sabin Point here, at the head of Narragansett Bay, to watch not one, but 64 balls, drop.

But unlike the ball drop to kick off the New Year, these balls are more like dome-shaped mounds, flat on the bottom, made of concrete and silica and hollow, three feet high and four feet wide, and with large holes gouging their surfaces. Their purpose: bring sport fish to Sabin Point.

These balls will create an artificial reef, the first of its kind in Rhode Island, as a result of a partnership between The Nature Conservancy and the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM).

“Part of this work began four years ago when DEM and The Nature Conservancy partnered up to start monitoring the upper bay, and through this we decided this location would be good for fish enhancement since it has access to fish by shore, not just by boat,” said Patrick Barrett, a DEM fisheries specialist. “The money used for this was raised and provided by taxes on fishing gear, so we’re trying to give back to the community.”

Specialty Diving transported the 64 reef balls via barge from Quonset Point to Sabin Point.

Many sport fish, specifically tautog, scup, and sea bass, like structured spaces, and, according to Tim Mooney of The Nature Conservancy, the reefs will allow minnows the security to grow into adulthood.

“The reefs should attract these fish and we’re hoping that it will increase their survival rate,” he said.

As part of the installation, DEM and The Nature Conservancy will monitor the progress in this location against other areas in the bay.

“We will be monitoring this area once a month, and every fall we’ll probably dive the reef as well,” Barrett said. “We’re interested to see what happens.”

Grace Kelly is an ecoRI News journalist.

Editor’s note: Supports for offshore wind turbines also attract fish.

A kind of resort

In the Waterloo Historic District, in Warren, N.H. It encompasses the site of one of the first mills on the Warner River.

“The seldom-traveled dirt road by their door

is where, good days, the Scutzes take their ease.

It serves as a living room, garage, pissoir

as well as barnyard. Hens scratch and rabbits doze

under cars jacked up on stumps of trees.’’

From the ‘‘Leisure’’ section of “Saga,’’ by Maxine Kumin (1925-14), a Pulitzer Prize-pwinning poet who from 1976 until her death lived with her she husband lived on a farm in Warner, N.H., where they bred Arabian and quarter horses.

Chase targets N.E. college students

Temporary headquarters of JPMorgan Chase, at 383 Madison Ave. in Manhattan

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“JPMorgan Chase & Co. plans to open dozens of retail branch locations around New England starting this year and into 2020. Chase (as it’s generally called) is the nation’s largest bank.

“Chase is optimistic about its growth plan for New England and is particularly interested in accessing the large student population in the region. At the end of September, the bank opened its first new retail location on Brown University’s campus, in Providence. In addition to 60 retail branches, Chase will also install over 130 ATM’s in the region. Chase, which currently employs more than 1,500 people in New England, plans to hire over 350 people through this regional expansion. The next New England branch to open will be in Dedham, Mass., in mid-December.’’

David Warsh: The Nobel Prize in Economics and the 'Methods Revolution'

Scurvy-prevention pioneer James Lind

The cure for scurvy became known to Portuguese explorer Vasco Da Gama when, in 1498, he stopped in Mombassa, along the east coast of Africa, on his way to India – the first such maritime voyage by a European in history. The African king fed the ship’s sailors oranges and lemons, and the disease, which often can be fatal to sailors on ships that remain at sea longer than 10 weeks, cleared up. The remedy became a naval secret, then a rumor, and, eventually, folk wisdom. Only in 1747, when British Navy surgeon James Lind performed his famous experiment, did it become reliable knowledge.

Lind divided 12 men suffering from similar symptoms aboard his ship into six pairs. He treated one man in each pair with one of six competing nostrums, and gave the other man nothing. Those who received citrus juice recovered while the others did not. It took another 40 years (and the onset of a desperate war with France) for the British Admiralty to require a ration of lemon juice be provided regularly to sailors throughout the fleet. Not until the 1930s did biochemist Albert Szent-Györgyi pin down that it is ascorbic acid, AKA vitamin C, that does the trick.

Since then, the practice of inferring causation by comparing a “treatment group” receiving a certain intervention with a “control group” receiving nothing of the sort has been considerably refined. Agronomists began using the technique in the early 20th Century to improve plant yields through hybridization. Statisticians soon tackled the problem of experiment design. The first randomized controlled trials in medicine were reported in 1948 – the effectiveness of streptomycin in treating tuberculosis.

Beginning in the 1980s, economists began adopting the technique of randomized control trials to use across a broad swathe of microeconomics, distinguishing between “natural experiments,” in which nature or history formulates the treatment and control groups, and “field experiments,” in which investigators arrange interventions themselves and then follow their effects on participants making decisions in everyday life.

Early experiments with negative income taxes by others were assessed by Jerry Hausman and David Wise in 1985,; the RAND Health Insurance Experiment, analyzed by Joseph Newhouse, in 1993; a series a welfare- reform experiments conducted by economic consulting firms for the Ford Foundation in the the ’80s and ’90s, surveyed by Charles Manski and Irwin Garfinkel in 1992; and experiments in early-childhood education, especially the Perry Preschool Project, begun in 1963, and introduced to economists by Lawrence Schweinhart, Helen Barnes, and Weikart, in 1993. An especially striking exemplar of the new approach came from Angrist in 1990 who used the draft lottery to study the effect of Vietnam-era conscription on lifetime earning.

Behind the scenes, of course, enabling the revolution, was the advent of essentially unlimited computing power and the software to put it to use, searching out all kinds of new data and analyzing it. Major developments along the way were described by Hausman and Wise (Social Experimentation, 1985); James Heckman and Jeffrey Smith, “Assessing the Case for Social Experiments,” 1995; Glenn Harrison and John List (“Field Experiments,” 2004); Angrist and Jörn-Steffen Pischke (“The Credibility Revolution in Empirical Economics,” 2010); David Card, Steffano DellaVigna, and Ulrike Malmendier (“The Role of Theory in Field Experiments,” 2011); Manski (Public Policy in an Uncertain World: Analysis and Decisions, 2013); and Susan Athey and Guido Imbens (“The Econometrics of Randomized Experiments,” 2017). All this can be gleaned from the first few pages of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences’ Scientific Background to this year’s Nobel Prize.

Confronted with this Tolstoyan sprawl, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences committee earlier this month finessed the problem of allocating credit by singling out the sub-discipline of development economics as a field in which experiments is said to have shown particular promise. Recognized were Abhijit Banerjee, 58, and Esther Duflo, 46, both of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and Michael Kremer, 55, of Harvard University, for having pioneered the use of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to assess the merits of various anti-poverty interventions.

In Duflo, the committee got what it wanted: a female laureate in economics, only the second to be chosen, and a young one at that. (Elinor Ostrom, then 78, who was honored with Oliver Williamson in 2009, died two years after receiving the award.) Duflo’s mother was a pediatrician who traveled frequently to Rwanda, Haiti and El Salvador to treat impoverished children or victims of war, according to Herstory. Duflo herself formed a life-long obsession with India at the age of six, when reading a comic book about Mother Teresa, the Albanian nun who operated a hospice in Calcutta (now Kolkata). As a student at the Ecole Normale Superieure, Duflo switched to economics from history while working for a year in Russia, observing the work of American economic advice-givers first hand. Duflo was Kremer’s and Banarjee’s student at MIT; the university hired her upon graduation, and tenured her after Princeton sought to lure her away.

Banerjee grew up in Kolkata, the son of a distinguished professor of economics. An interview with The Telegraph gives a vivid picture of the rich intellectual life of Bengal. He earned his PhD from Harvard in 1988 with a trio of essays in information economics, and taught at Princeton, then Harvard, before moving to MIT. There he founded, in 2003, with Duflo, Kremer and others, the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, known colloquially as J-PAL, its researchers self-identifying as randomistas. In 2010, he and Duflo published Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty (Public Affairs), a primer on RCTs. By then he had divorced his first wife. In 2015, he and Duflo married.

Of the three, Kremer was the pioneer. After graduating from Harvard College, in 1985, he taught high school in Kenya for a year. Returning to Harvard to study economics with Robert Barro, in a period of great ferment, he made two durable contributions to what was then the “new” economics of growth: “Population Growth and Technological Change: 1.000,000 BC to 1990” and “The O-Ring Theory of Economic Development,” both in 1993. With “Research on Schooling: What We Know an What We Don’t,” in August 1995, Kremer asked a series of questions; six months later, in “Integrating Behavioral Choice into Epidemiological Models of the AIDS Epidemic,” he developed a model of a different problem whose implications might be tested with a new approach: randomized control trials. Since then, he has kept up a drumbeat of influential papers – health treatments, patent buyouts, elephant conservation, vaccine-purchase commitments, the repeal of odious debt – including several with his wife, the British economist Rachel Glennerster.

“The research conducted by this year’s Laureates has considerably improved our ability to fight global poverty,” asserted the Nobel press release. “In just two decades, their new experiment-based approach has transformed development economics, which is now a flourishing field of research.” One reason it is flourishing is the availability of a deep river of global funding: The World Bank, the United Nations, and several major philanthropies regularly invest enormous sums in development research compared to other areas of inquiry. Those projects offering carefully designed experiments, promising reliable answers to perplexing questions, enjoy a significant advantage in the competition for research funds.

For a well-informed description of some of the work and its limitations, see Kevin Bryan’s post at A Fine Theorem, “What Randomization Can and Cannot Do.” For some sharp criticism, read “The Poverty of Poor Economics,” on Africa Is a Country’s site. (“Serious ethical and moral questions have been raised particularly about the types of experiments that the randomistas… have been allowed to perform.”) Remember, too, that problems of agricultural policy that are fundamental to poverty reduction are far beyond the reach of RCTs to deliver answers. How to escape the middle income trap? How to build a research system to reach the technological frontier?

And to be reminded that commerce routinely alleviates more poverty around the world than aid (though hardly all), read veteran Financial Times correspondent David Pilling’s recent dispatch on Africa’s increasingly dynamic interaction with the rest of the world, China in particular. “When most people think of China in Africa,” he writes, “they think of mining and construction. But things are moving on. It is no longer the highways where the main action is taking place. It is the superhighways,” he says, of e-commerce in particular.

In short, to speak of a “credibility revolution” seems to me mainly a marketing slogan; it overstates the contribution that the small steps that RCTs are delivering, compared to those of theory prior to investigation. “Methods revolution” is a more neutral term. But that said, the Nobel panel neatly solved its problems for another year. The prize for RCTs in development economics is the first step in what will surely be a series of prizes to be given for new methods-driven results. There will be many more.

David Warsh, an economic historian and a veteran columnist, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

To final markup

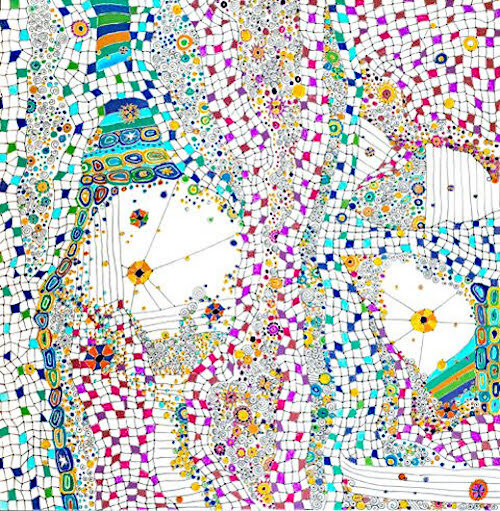

Untitled (ink on wood panel), by Lois Guarino, in her show at the Augusta Savage Gallery at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, through Nov. 26.

She creates her pen drawings by making marks, which, the gallery says, “she follows obsessively until completion.’’

A WASP 'refugee'

Spalding Gray in about 1980

The Congregational church in the affluent town of Barrington, R.I.

“I was raised as an upper-class WASP in New England, and there was this old tradition there that everyone would simply be guided into the right way after Ivy League college and onward and upward. And it rejected me, I rejected it, and I ended up as a kind of refugee, really.’

— Spalding Gray (1941-2004), a writer and actor who grew up in Barrington, R.I., where many of his autobiographical stories are based. He died an apparent suicide after jumping into the East River in New York City.

He was particularly famous for his monologues, delivered in a dry , upper-crust New England voice and with a poker face.

'Lone wandering, but not lost'

“Wood Duck (1915), by Chester A. Reed, from The Bird Book

Whither, midst falling dew,

While glow the heavens with the last steps of day,

Far, through their rosy depths, dost thou pursue

Thy solitary way?

Vainly the fowler's eye

Might mark thy distant flight to do thee wrong,

As, darkly painted on the crimson sky,

Thy figure floats along.

Seek'st thou the plashy brink

Of weedy lake, or marge of river wide,

Or where the rocking billows rise and sink

On the chafed ocean side?

There is a Power whose care

Teaches thy way along that pathless coast,—

The desert and illimitable air,—

Lone wandering, but not lost.

All day thy wings have fanned,

At that far height, the cold, thin atmosphere,

Yet stoop not, weary, to the welcome land,

Though the dark night is near.

And soon that toil shall end;

Soon shalt thou find a summer home, and rest,

And scream among thy fellows; reeds shall bend,

Soon, o'er thy sheltered nest.

Thou'rt gone, the abyss of heaven

Hath swallowed up thy form; yet, on my heart

Deeply hath sunk the lesson thou hast given,

And shall not soon depart.

He who, from zone to zone,

Guides through the boundless sky thy certain flight,

In the long way that I must tread alone,

Will lead my steps aright.

— “To a Waterfowl” (1818), by William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878), a western Massachusetts native who moved to New York City and became a major American literary figure

Llewellyn King: My globetrotting in Kindle

— Image by Evan-Amos

Read any good books lately? As a matter of fact, I have. Quite a few.

We’re expected to plow through great stacks of books over the summer; perhaps a throwback to a time when people on vacation were quite bored. But for me, it was a good summer of reading.

A confession: I don’t read to improve my mind, to understand what skullduggery this president — any president — is up to, or what venality drives the great houses of commerce.

I read to spend a spot of time with other people. When I get a book that interests me, I move in. I take lodgings, as it were, with the people I’m reading about, whether it is great historical figures, say Conde Nast, or the denizens of works of fiction like those to be found in good detective stories — such as the Chief Inspector Banks novels by Peter Robinson, an English author who lives in Canada and sets his stories in the North of England. Or, I move to Venice in the mysteries of Donna Leon, an American who sets her Commissario Guido Brunetti series there.

Historical or fictional, I hang out with the subjects in books. I join families, police stations, cabinets, regiments, love affairs and just good friends.

This escapism for me is vastly enhanced by the fact that I’m a slow reader. But if it weren’t for my slow reading, I wouldn’t have long to live my man-who-dropped-in fantasy life. A sadness descends when I’m near the end of my sojourn with strangers and I realize that, in a half an hour or so, I’ll have to leave, endure separation, sorrow.

In recent years, technology has added to my ability to sojourn whenever I like: The technology is the Kindle, the Amazon device. As much as I deplore what electronic publishing has done to the craft of book making and to newspaper production, it has added a wonderful portability to my reading.

The electronic reader is a manageable size and slips easily into a pocket. I’m glad when someone is late because I can read for a few minutes. What used to be an inconvenience has become a gift. Waiting for the doctor or being put on hold, while a recorded voice advises “one of our representatives will be with you shortly,” becomes an opportunity to take a quick trip somewhere else.

So, what did I do on my summer vacation — the one I didn’t take because I was too busy and too broke? I had a fabulous time in the 18th century with an extraordinary group of men, and a few women, who shaped the thinking of that time and whose influence has stayed with us to this day. The book, strongly recommended, is The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age, by Harvard professor of literature emeritus Leo Damrosch.

I also hugely enjoyed my stay in London with Vanessa and Her Sister: A Novel, by Priya Parmar. It’s all about the Bloomsbury Set circa 1907, about Virginia Woolf and many other writers and artists. They were very open about homosexuality, sex in general and arranged each other’s relationships with abandon.

My time in Wyoming was enlightening and enjoyable in J.L. Doucette’s crime mystery novel Last Seen. Doucette brings to life the hard times and interesting happenings in Sweetwater County, Wyo., featuring psychologist Dr. Pepper Hunt and Native American detective Antelope.

I dug into the complexities of sex and creativeness in Francine Prose’s The Lives of the Muses: Nine Women and the Artists They Inspired. Her book takes you from Man Ray and Elizabeth “Lee” Miller to Salvador Dali and Gala. As I met Dali several times, I found his relationship with his love Gala fascinating.

Right now, I’m hanging out in Australia with the characters of Liane Moriarty, one of the great fiction writers of our time. I’ve hung out with her characters in other books, but this time with those in Nine Perfect Strangers.

Armchair travel has joined the electronic age for me. Up, up and away!

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

William Morgan: Treasures from the 50-cent photo bin

The best part of any New England antique shop, for my money, is the old photos. In some higher-end boutiques the postcards and pictures can be $5 apiece or more. But I struck pay dirt in Bowerbird & Friends, in Peterborough, N.H., which has scores of snapshots for 50¢ each. I bought five mysterious images.

The majority of those in the photo basket are 3 ½ -inch-square prints from the trusty Brownie box cameras of the 1950s.

There is a certain pathos in all these discarded records from a pre-digital age. While, far too few of these have any notation who and where the people are, this octet of friends is identified as "Picnic at Lillian Bliss Summer house in Otis" (Massachusetts, presumably), dated most accurately by the loafers and bobby sox.

Almost as typical is the earlier 20th-Century group photo posed before a church. The picture is 4 by 2 ½ inches.

The faded color of this mystery photo would seem to be earlier than the Nov. 73 date stamped on the back. At first, this appeared to be a man with a still, but on closer inspection the plastic jugs seem to hold apple cider. How New England, how autumnal.

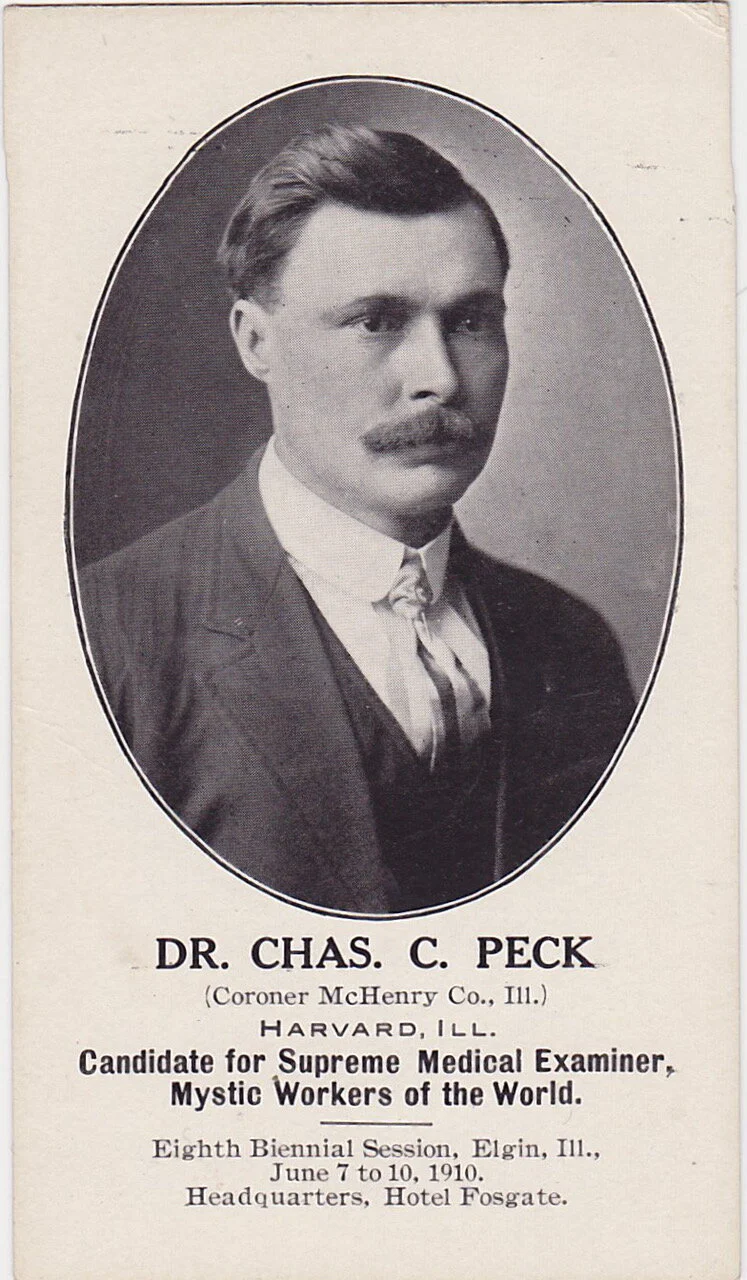

Even odder is the 2 ½-by-4 ½ inch carte de visite of Dr. Chas. C. Peck, the coroner of McHenry County, Ill., from the summer of 1910. Or perhaps it is a political handout, as our lugubrious-looking Dr. Peck is a candidate for Supreme Medical Examiner, Mystic Workers of the World. Despite its dark title, the Workers were a Midwestern fraternal organization that sold insurance to its members. Their medical examiners presumably decided on whom should be underwritten and who was too much of a risk, or in Peck's case, if they were still among the living.

Strangest of the quintet of Peterborough oddities is this photograph of wedding guests from Aug. 3, 1963, in an era when most women still wore hats to such events, not to mention pearls. The picture was taken by Robert English, probably the state senator from nearby Hancock, N.H. (whose district included Peterborough and Dublin). The ceremony was perhaps taken at the tony Dublin Lake Club, where the senator's daughter was married three years later. Just an amateur shot, perhaps, but English has really captured a slice-of-life social commentary: the moneyed Republican couple, the grand dame, and frumpy and awkward daughter.

William Morgan, a Providence-based essayist and architectural historian, has taught the history of photography at Princeton University and is the author of Monadnock Summer: The Architectural Legacy of Dublin, New Hampshire.