Vox clamantis in deserto

Julie Walsh: Dangerous misinformation campaigns from medieval Europe to today’s social media

Representation of the Salem witch trials (1692-1693) lithograph from 1892

Torturing woman accused of witchcraft, in this 1577 picture.

From The Conversation, except for images above

Julie Walsh is Whitehead Associate Professor of Critical Thought and Associate Professor of Philosophy, Wellesley College

She receives funding from the National Science Foundation

WELLESLEY, Mass.

Between 1400 and 1780, an estimated 100,000 people, mostly women, were prosecuted for witchcraft in Europe. About half that number were executed – killings motivated by a constellation of beliefs about women, truth, evil and magic.

But the witch hunts could not have had the reach they did without the media machinery that made them possible: an industry of printed manuals that taught readers how to find and exterminate witches.

I regularly teach a class on philosophy and witchcraft, where we discuss the religious, social, economic and philosophical contexts of early modern witch hunts in Europe and colonial America. I also teach and research the ethics of digital technologies.

These fields aren’t as different as they seem. The parallels between the spread of false information in the witch-hunting era and in today’s online information ecosystem are striking – and instructive.

Birth of a publishing empire

The printing press, invented around 1440, revolutionized how information spread – helping to create the era’s equivalent of a viral conspiracy theory.

By 1486, two Dominican friars had published the “Malleus Maleficarum,” or “Hammer of Witches.” The book has three central claims that came to dominate the witch hunts.

A 1669 edition of ‘Malleus Maleficarum.’ Wellcome Collection/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

First, it describes women as morally weak and therefore more likely to be witches. Second, it tightly links witchcraft with sexuality. The authors claim that women are sexually insatiable – part of what leads them to witchcraft. Third, witchcraft involves a pact with the devil, who tempts would-be witches through pleasures such as orgies and sexual favors. After establishing these “facts,” the authors conclude with instructions for interrogating, torturing and punishing witches.

The book was a hit. It had more than two dozen editions and was translated into multiple languages. While “Malleus Maleficarum” was not the only text of its kind, its influence was enormous.

Prior to 1500, witch hunts in Europe were rare. But after the “Malleus Maleficarum,” they picked up steam. Indeed, new printings of the book correlate with surges in witch-hunting in Central Europe. The book’s success wasn’t just about content; it was about credibility. Pope Innocent VIII had recently affirmed the existence of witches and conferred authority on inquisitors to persecute them, giving the book further authority.

Ideas about witches from earlier texts and folklore – such as the “fact” that witches could use spells to make penises vanish – were recycled and repackaged in the “Malleus Maleficarum,” which in turn served as a “source” for future works. It was often quoted in later manuals and woven into civic law.

The popularity and influence of the book helped crystallize a new domain of expertise: demonologist, an expert on the nefarious activities of witches. As demonologists repeated one another’s spurious claims, an echo chamber of “evidence” was born. The identity of the witch was thus formalized: dangerous and decisively female.

Skeptics fight back

Not everyone bought into the witch hysteria. As early as 1563, dissenting voices emerged – though, notably, most didn’t argue that witches weren’t real. Instead, they questioned the methods used to identify and prosecute them.

Essayist Michel de Montaigne, painted around 1578 by an unknown artist. Conde Museum/Wikimedia Commons

Dutch physician Johann Weyer argued that women accused of witchcraft were suffering from melancholia – what we might now call mental illness – and needed medical treatment, not execution. In 1580, French philosopher Michel de Montaigne visited imprisoned witches and concluded they needed “hellebore rather than hemlock”: medicine rather than poison.

These skeptics also identified something more insidious: the moral responsibility of people spreading the stories. In 1677, English chaplain, physician and philosopher John Webster wrote a scathing critique, claiming that most demonologists’ texts were straightforward copy and paste jobs where the authors repeated one another’s lies. The demonologists offered no original analysis, no evidence and no witnesses – failing to meet the standards of good scholarship.

The cost of this failure was enormous. As Montaigne wrote, “The witches of my neighborhood are in mortal danger every time some new author comes along and attests to the reality of their visions.”

Demonologists benefited from the social and political status associated with the popularity of their books. The financial benefit was, for the most part, enjoyed by the printers and booksellers – what today we refer to as publishers.

Witch hunts petered out throughout the 1700s across Europe. Doubt about the standards of evidence, and increased awareness that accused “witches” may have been suffering from delusion, were factors in the end of the persecution. The skeptics’ voices were heard.

Psychology of viral lies

Early modern skeptics understood something we’re still grappling with today: Certain people are more vulnerable to believing extraordinary claims. They identified “melancholics,” people predisposed to anxiety and fantastical thinking, as particularly susceptible.

Nicolas Malebranche, a 17th-century French philosopher, believed that our imaginations have enormous power to convince us of things that are not true – especially fear of invisible, malevolent forces. He noted that “extravagant tales of witchcraft are taken as authentic histories,” increasing people’s credulity. The more stories, and the more they were told, the greater the influence on the imagination. The repetition served as false confirmation.

“If they were to cease punishing (women accused of witchcraft) and treat them as mad people,” Malebranche wrote, “in a little while they would no longer be sorcerers.”

The title page of a treatise on witchcraft from 1613. Wellcome Collection/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Today’s researchers have identified similar patterns in how misinformation and disinformation – false information intended to confuse or manipulate people – spreads online. We’re more likely to believe stories that feel familiar, stories that connect to content we’ve previously seen. Likes, shares and retweets becomes proxies for truth. Emotional content designed to shock or outrage spreads far and fast.

Social media channels are particularly fertile ground. Companies’ algorithms are designed to maximize engagement, so a post that receives likes, shares and comments will be shown to more people. The more viewers, the higher the likelihood of more engagement, and so on – creating a cycle of confirmation bias.

Speed of a keystroke

Early modern skeptics reserved their harshest criticism not for those who believed in witches but for those who spread the stories. Yet they were curiously silent on the ultimate arbiters and financial beneficiaries of what got printed and circulated: the publishers.

Today, 54% of American adults get at least some news from social media platforms. These platforms, like the printing presses of old, don’t just distribute information. They shape what we believe through algorithms that prioritize engagement over accuracy: The more a story is repeated, the more priority it gets.

The witch hunts offer a sobering reminder that delusion and misinformation are recurring features of human society, especially during times of technological change and social upheaval. As we navigate our own information revolution, those early skeptics’ questions remain urgent: Who bears responsibility when false information leads to real harm? How do we protect the most vulnerable from exploitation by those who profit from confusion and fear?

In an age when anyone can be a publisher, and extravagant tales spread at the speed of a keystroke, understanding how previous societies dealt with similar challenges isn’t just academic – it’s essential.

Chris Powell: Remediate Conn.’s present before repudiating its past

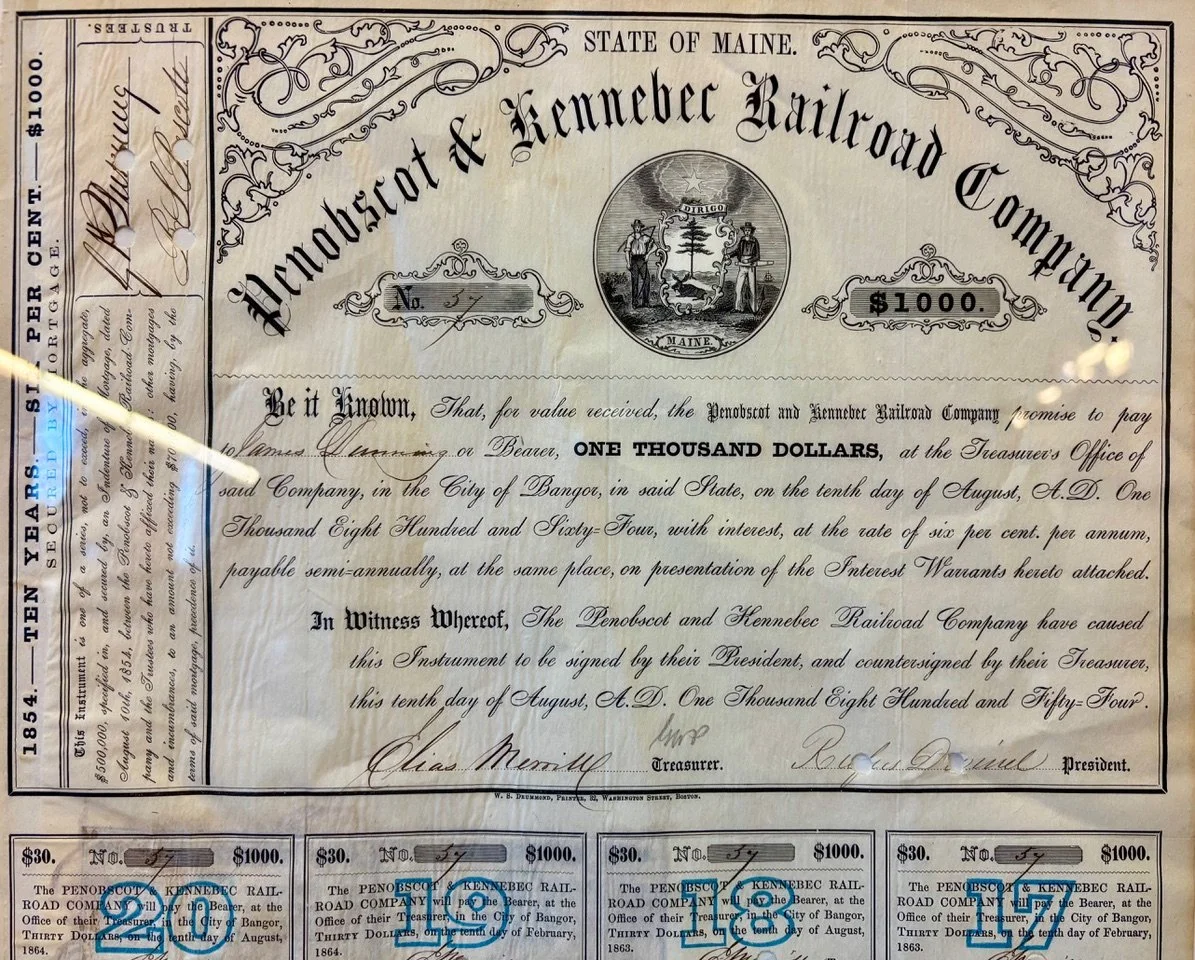

At the Salem Witch trials

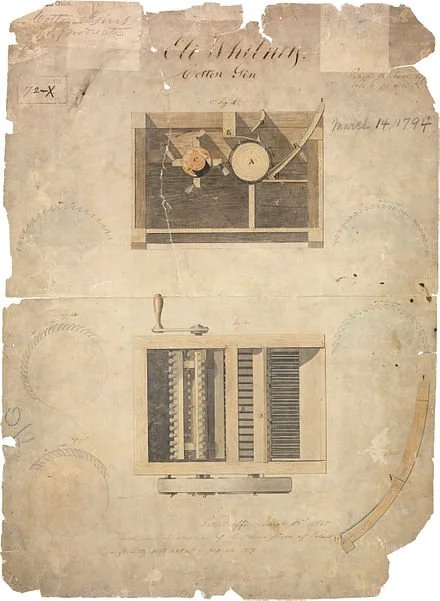

Connecticut inventor Eli Whitney's (1765-1825) original cotton gin patent, dated March 14, 1794. The invention lead to a huge expansion of slavery and thus to the Civil War.

MANCHESTER

While the new state budget wasn't yet complete, with several big issues waiting to be settled, the other day the state House of Representatives found time to pass a resolution that more or less repudiated and apologized for the conviction and execution of people alleged to have been witches in the Connecticut colony 400 years ago.

Advocates of the resolution said it was needed to assuage the feelings of the distant descendants of the wrongly prosecuted, though if there really are any people with feelings so tender, they need a legislative resolution less than round-the-clock sedation.

For does anyone in Connecticut consider witchcraft convictions from centuries ago to be a mark of shame against anyone alive today?

While the witchcraft resolution was being considered, Connecticut's news was full of reports about matters whose shame is contemporaneous -- like the miserable educational performance of children from racial minorities, the growing violence in the cities, the mental illness and drug addiction of most of the offenders being released from prison, the rise in poverty and homelessness, and worsening social disintegration that suggests the state has become the set of a zombie movie.

The General Assembly has yet to repudiate or apologize for any of those things. For doing something about them would require profound changes in government policy and probably substantial appropriations, even as posturing self-righteously with a resolution of no practical help to anyone is free.

But more discouraging than the legislature's propensity for stupid posturingis the growing presumption that inspired and advanced the witchcraft resolution and inspires other claims for apologies or reparations -- the presumption that the past is so bad that it should shame everyone in the present.

Of course, some shameful things from long ago have present consequences that may be remediable. The disproportionate failure of students from minority groups may be considered the consequence of slavery, though slavery ended 160 years ago. It may be considered the consequence of prejudicial policies that ended 50 years ago, though far more recent policies may be at fault, policies no one in authority cares to question.

In any case the natural order has been for mankind to advance over long periods -- to gain knowledge, wisdom, and decency so that, for example, prosecutions for "familiarity with the Devil" are understood as unjust and based on the superstition and irrational fear inherent in ignorance.

That society improves gradually used to be understood as what was called the ascent of man. Painful as that ascent sometimes has been, ascent it was, and no shame attaches to those who did not participate in old injustices, a point that the opponents of the House resolution on witchcraft tried to make.

Besides, once society begins apologizing for the mistakes of the distant past, there may be no end to it even as its only practical effect will be to provide distraction from the mistakes of the present, just as the witchcraft resolution has done.

xxx

In a desperate attempt to regain ratings a few weeks ago, CNN partnered with former President Donald Trump in televising a public forum in New Hampshire that was packed with Trump supporters while hostile questions were posed to Trump by reporter Kaitlan Collins.

Running for president for a third time, Trump got exactly what he wanted -- another chance to behave outlandishly, call names, and demonstrate the demeanor that has troubled even people who favored some of his administration's policies.

The audience in New Hampshire loved it, providing more evidence that nothing disgraceful, from mere lies to graft to sexual assault, can hurt Trump with his base. As he discovered with happy surprise when he began his first campaign for president in 2016, "I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn't lose any voters."

Trump is the embodiment of the contempt our government increasingly deserves.

Responding to the CNN broadcast, President Biden asked the country: "Do you want four more years of that?" But seeking re-election, the doddering and gaffe-producing Biden, a tool of wokeism, is himself why many people might choose four more years of Trump.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Connecticut. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

Chris Powell: Feel guilty about the present, not the past

“Examination of a {New England} Witch,” by Tompkins Harrison Matteson (1813-1884), at the Peabody Essex Museum, in Salem, Mass.

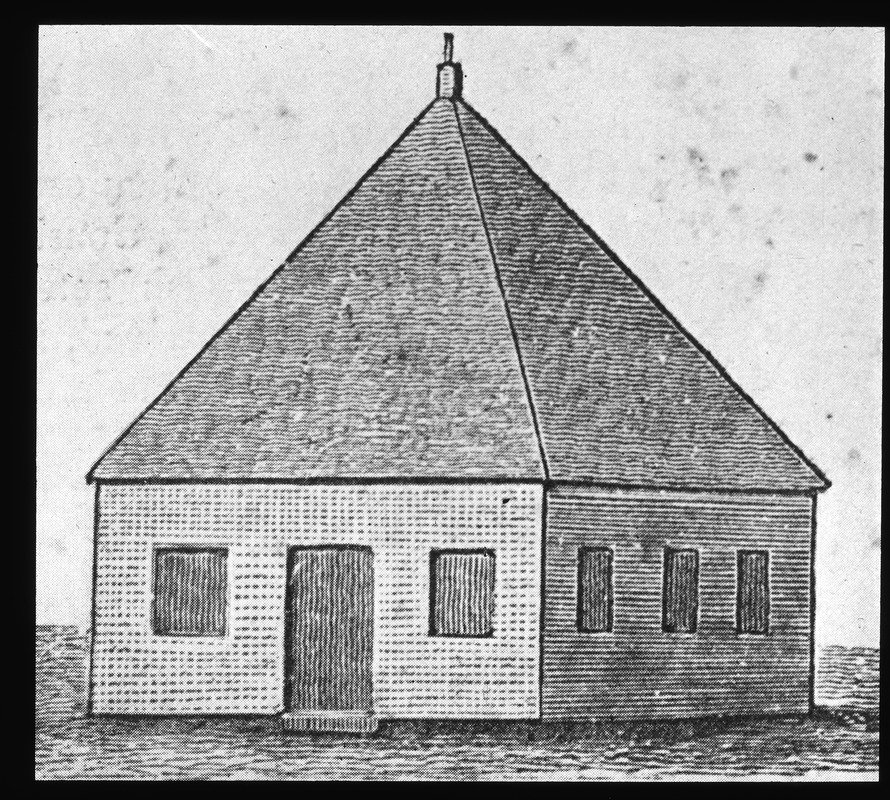

The First Meeting House, in Hartford, built in 1635, in the neighborhood where executions for witchcraft took place.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Guilt tripping through American history has become almost as popular for vacationers as Florida. It's a vacation from current political reality.

In Connecticut the latest guilt trip involves the executions carried out here in the 1600s by the earliest European colonists against 11 of their number accused of witchcraft. The first known witchcraft execution in North America was that of a Windsor woman who was hanged in Hartford in 1647. This was just eight years after the Connecticut colony had distinguished itself more favorably by adopting the Fundamental Orders, a constitution establishing a government and taking more small steps toward democracy.

Until recently Connecticut preferred to remember the heroic virtues of its founders -- their setting out on their own, crossing the ocean, and starting up all over again from nothing. But their failings, even their witchcraft hysteria, are not really cause for the everlasting shame pursued by today's guilt tripping, which takes people and events out of the context of their time and ignores what used to be called the ascent of man, the long and bumpy journey from primitiveness to civilization.

For of course hundreds of years ago people saw the world in a more primitive way, without the understanding provided by modern science and communications. The fear arising from their lack of understanding, combined with the severity of their Puritan religion, made witchcraft seem a plausible explanation for the frequent calamities they suffered, and an accusation of witchcraft quickly became a convenient mechanism for intimidating or expropriating others -- much as accusations of racism are exploited today.

A group called the Connecticut Witch Trial Exoneration Project has been clamoring for a formal acquittal of the victims of the witchcraft hysteria. The state's pardon law can't help because it can be applied only to the living, so maybe it could be amended. Or maybe the General Assembly could pass a resolution of apology.

But why bother? Is there anyone in the state or even the country who has heard of the old witchcraft hysteria and who doesn't know that it was all a horrible misapprehension and injustice and who doesn't either shudder or laugh at it? Could anyone unaware of it come upon it without instantly recognizing it as such?

Meanwhile there are many criminal convictions throughout the country about which serious doubts have arisen, and a far more relevant project, the Innocence Project, has used DNA evidence and other investigation to exonerate hundreds of wrongly convicted people, including some in Connecticut -- people who are still alive and thus in infinitely more need of exoneration than the supposed witches of old. The Innocence Project estimates that as many as 10 percent of prisoners held in the United States are innocent. (Also unjustly, many repeat criminal offenders stalk society because the criminal-justice system fails to put them away for good no matter how much harm they keep doing.)

Many wrongly accused people have been convicted on the basis of false confessions, extracted from them by intimidation and threats by police and prosecutors, just as false confessions were sweated or even beaten out of people accused of witchcraft.

That's why any formal exoneration of the victims of the witchcraft hysteria won't do much more than make people feel guilty about a wrong done long ago for which they bear no responsibility even as it distracts them from current wrongs for which everyone remains responsible.

OUTRAGEOUS INEPTNESS: Connecticut has all sorts of outrages that should be addressed before bothering with the flaws of ancient ancestors. Another such outrage arose three weeks ago in Stonington, where, according to The Day of New London, two municipal public-works employees were caught on surveillance video planting drug syringes in a gazebo in a town park, and doing it on the job, no less.

Police said the employees aimed to create the false impression that the park is overrun by drug addicts and crime.

But Stonington First Selectwoman Danielle Chesebrough says the employees will not be disciplined because their dangerous and deceitful stunt violated no town government policy.

Indeed, all Connecticut often seems to lack a policy ensuring that government serves the public rather than its own employees.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.