Vox clamantis in deserto

Emily Greene-Colozzi: There’s a lack of evidence that tech stops school shootings

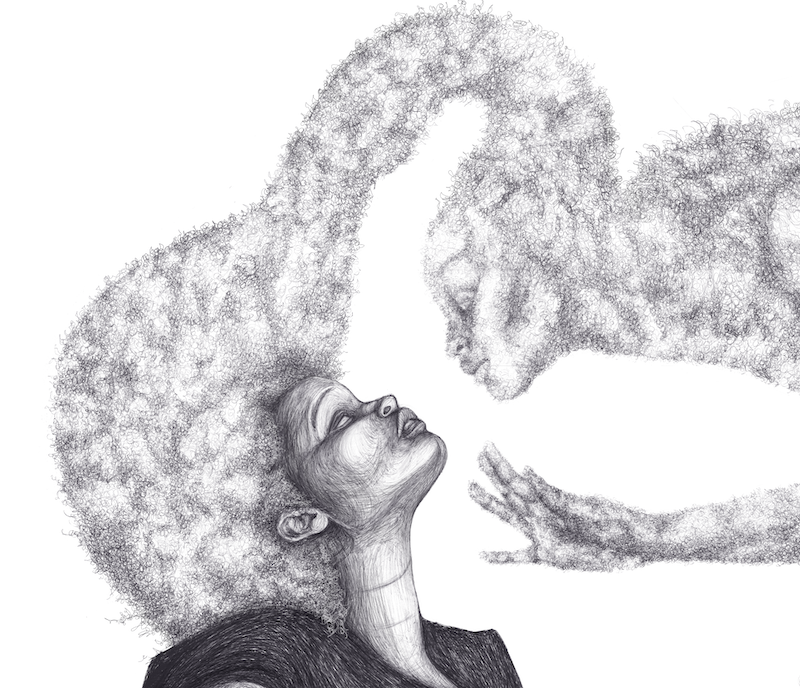

Memorial flowers outside the Brown engineering complex, where the shootings happened.

Via The Conversation, except for the image above.

Emily Greene-Colozzi is an assistant professor of criminology and justice studies at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell. She receives funding from the National Institute of Justice.

A group of college students braved the frigid New England weather on Dec. 13, 2025, to attend a late- afternoon review session at Brown University, in Providence. Eleven of those students were struck by gunfire when a shooter entered the lecture hall. Two didn’t survive.

Shortly after, a petition circulated calling for better security for Brown students, including ID-card entry to campus buildings and improved surveillance cameras. As often happens in the aftermath of tragedy, the conversation turned to lessons for the future, especially in terms of school security.

There has been rapid growth of the nation’s now $4 billion school security industry. Schools have many options, from traditional metal detectors and cameras to gunshot detection systems and weaponized drones. There are also purveyors of artificial-intelligence-assisted surveillance systems that promise prevention: The gun will be detected before any shots are fired, and the shooting will never happen.

They appeal to institutions struggling to protect their communities, and are marketed aggressively as the future of school shooting prevention.

I’m a criminologist who studies mass shootings and school violence. In my research, I’ve found that there’s a lack of evidence to support the effectiveness of these technological interventions.

Grasping for a solution

Implementation has not lagged. A survey from Campus Safety Magazine found that about 24% of K-12 schools report video-assisted weapons detection systems, and 14% use gunshot detection systems, like ShotSpotter.

Gunshot detection uses acoustic sensors placed within an area to detect gunfire and alert police. Research has shown that gunshot detection may help police respond faster to gun crimes, but it has little to no role in preventing gun violence.

Still, schools may be warming to the idea of gunshot detection to address the threat of a campus shooter. In 2022, the school board in Manchester, N.H., voted to implement ShotSpotter in the district’s schools after a series of active-shooter threats.

Other companies claim their technologies provide real-time visual weapons detection. Evolv is an AI screening system for detecting concealed weapons, which has been implemented in more than 400 school buildings since 2021. ZeroEyes and Omnilert are AI-assisted security camera systems that detect firearms and promise to notify authorities within seconds or minutes of a gun being detected.

These systems analyze surveillance video with AI programs trained to recognize a range of visual cues, including different types of guns and behavioral indicators of aggression. Upon recognizing a threat, the system notifies a human verification team, which can then activate a prescribed response plan

.

But even these highly sophisticated systems can fail to detect a real threat, leading to questions about the utility of security technology. Antioch High School in Nashville, Tennessee, was equipped with Omnilert’s gun detection technology in January 2025 when a student walked inside the school building with a gun and shot several classmates, one fatally, before killing himself.

School security technology firm ZeroEyes uses this greenscreen lab to test and train artificial intelligence to spot visible guns. AP Photo/Matt Slocum

Lack of evidence

This demonstrates an enduring problem with the school security technology industry: Most of these technologies are untested, and their effect on safety is unproven. Even gunshot-detection systems have not been studied in the context of school and mass shootings outside of simulation studies. School shooting research has very little to offer in terms of assessing the value of these tools, because there are no studies out there.

This lack is partly due to the low incidence of mass and school shootings. Even with a broad definition of school shootings – any gunfire on school grounds resulting in injury – the annual rate across America is approximately 24 incidents per year. That’s 24 more than anyone would want, but it’s a small sample size for research. And there are few, if any, ethically and empirically sound ways to test whether a campus fortified with ShotSpotter or the newest AI surveillance cameras is less likely to experience an active shooter incident because the probability of that school being victimized is already so low.

Existing research provides a useful overview of the school safety technology landscape, but it offers little evidence of how well this technology actually prevents violence. The National Institute of Justice last published its Comprehensive Report on School Safety Technology in 2016, but its finding that the adoption of biometrics, “smart” cameras and weapons detection systems was outpacing research on the efficacy of the technology is still true today. The Rand Corporation and the University of Michigan Institute for Firearm Injury Prevention have produced similar findings that demonstrate limited or no evidence that these new technologies improve school safety and reduce risks.

While researchers can study some aspects of how the environment and security affect mass shooting outcomes, many of these technologies are too new to be included in studies, or too sparsely implemented to show any meaningful impact on outcomes.

My research on active and mass shootings has suggested that the security features with the most lifesaving potential are not part of highly technical systems: They are simple procedures such as lockdowns during shootings.

The tech keeps coming

Nevertheless, technological innovations continue to drive the school-safety industry. Campus Guardian Angel, launched out of Texas in 2023, promises a rapid drone response to an active school shooter. Founder Justin Marston compared the drone system to “having a SEAL team in the parking lot.” At $15,000 per box of six drones, and an additional monthly service charge per student, the drones are equipped with nonlethal weaponry, including flash-bangs and pepper spray guns.

In late 2025, three Florida school districts announced their participation in Campus Guardian Angel’s pilot programs.

Three school districts in Florida are part of a pilot program to test drones that respond to school shootings.

There is no shortage of proposed technologies. A presentation from the 2023 International Conference on Computer and Applications described a cutting-edge architectural design system that integrates artificial intelligence and biometrics to bolster school security. And yet, the language used to describe the outcomes of this system leaned away from prevention, instead offering to “mitigate the potential” for a mass shooting to be carried out effectively.

While the difference is subtle, prevention and mitigation reflect two different things. Prevention is stopping something avoidable. Mitigation is consequence management: reducing the harm of an unavoidable hazard.

Response versus prevention

This is another of the enduring limitations of most emerging technologies being advertised as mas-s shooting prevention: They don’t prevent shootings. They may streamline a response to a crisis and speed up the resolution of the incident. With most active shooter incidents lasting fewer than 10 minutes, time saved could have critical lifesaving implications.

But by the time ShotSpotter has detected gunshots on a college campus, or Campus Guardian Angel has been activated in the hallways of a high school, the window for preventing the shooting has long since passed.

Karen Gross: As school shootings continue, college students must ask if they're next

Scene at Sandy Hook Elementary School, in Newtown, Conn., on Dec. 14, 2012, when heavily armed 20-year-old Adam Lanza shot to death 26 people, including 20 children between six and seven years old, and six adult staff members. Before driving to the school, he shot to death his mother at their Newtown home. As first responders arrived at the school, Lanza committed suicide by shooting himself in the head.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

In a matter of seconds, a student at a high school in Santa Clarita, Calif., injured and killed a handful of his fellow students and then shot himself. He died shortly thereafter. We read about such incidents and lament their happening. We see television footage and peruse articles and social media postings. We mourn for the students injured and killed and worry about their families and friends.

And we wonder why this shooting happened. And we wonder why so many shootings happen.

Despite the usual outpouring of support for survivors and displays of empathy, those of us in higher education often don’t reflect on how all these K-12 shootings can and likely will affect us directly. We don’t consider how high school shootings will impact the college students we now have and the students we will have in the future—especially if we are geographically separated. It is as if we see the K-12 shootings as something that happens “over there” with “younger” students; meanwhile, we worry about a myriad of issues on our own campuses including potential shootings on campus, but also drug overdoses and sexual harassment.

The story that struck a chord

One particular story in the Los Angeles Times that got my attention. It was about how the shooting at the high school in Santa Clarita affected the students at a nearby elementary school. These younger students were preparing for a Thanksgiving pageant. The image of youngsters in their Pilgrim costumes crying upon learning of the shooting and being held in place at their school is fraught with irony: a supposed celebration of freedom and togetherness (even if sanitized by a retelling of our history with Native Americans) is disturbed by violence. No “Thanks” in this planned Thanksgiving pageant. While the emotions differed among the younger and somewhat older students at the elementary school, they were affected, as were their parents, according to the article and other reports.

Thinking about that story made me realize that many in higher education (with some exceptions of course) do not realize that trauma travels with a student forward in time. And it is as if trauma were in a suitcase and with the passage of time, that suitcase grows. As and when new traumas occur or there are new triggering events, the trauma suitcase expands and the holder of the suitcase experiences their autonomic nervous system on high alert.

As one author quoted in a recent article on student mental health stated, trauma sits in an invisible backpack that a student carries. What is in that suitcase/backpack affects not just the student him or herself; it affects those around the student, including those who teach them. That’s where secondary and vicarious trauma occur.

In sum, the reach of shootings is wide and deep and continuous.

Trauma and college students

The students who have experienced shootings will, one hopes, someday enter postsecondary education. But the institutions that will be serving them need to know that the trauma of the applicants, and later of enrolled students, does not get parked at the proverbial gate to higher education. And for those entering a residential college, with the transition into a dorm, the challenges are even greater: new roommate, new living situation, new location. For all new college students, there is a sense of disquiet when the new collegiate experience starts, and they are the “newbies,” even if they are enthusiastic, engaged and willing to learn.

We often use orientations at the start of college to inform students on a wide range of matters, including sexual policies, drug use, alcohol and mental health. We provide IDs, and paperwork is completed. We give out swipe cards. There are financial aid or bursar meetings. Residential assistants hold get-togethers. There are often placement tests.

And, sadly, we think students are absorbing all this, even when tempered with “get-to-know-you games.”

What is happening for many students is that their autonomic nervous systems are on high alert. They cannot really hear, absorb and process what they are being told. They are trying to find their way to the bathroom and are worried about their interpersonal and academic success. They may think they flunked the placement test. They didn’t really understand the financial aid repayment options. They wonder if there were people there who would like them. They may be lonely or feel separation anxiety.

While student life personnel may deal effectively with some of these issues, faculty tend to just launch right into their subjects as if being in college is anticipated, expected and everyone is ready to roll ahead in the disciplines of the courses they select. Then students receive a syllabus, which is often long and the name itself is off-putting for some. We assign massive reading and ask questions to which students don’t know the answers or are reluctant to answer.

And that’s just the first week.

Transitions are not our strong suit

Here’s my point: Going to college is a transition and if you have ever been traumatized in your past, that event was your first transition. You transitioned from not being traumatized to being traumatized. And, once traumatized, other transitions kick off negative signals since the first transition was bad, and tell the autonomic nervous system to be on high alert.

For students who have been traumatized in the past, who have experienced attachment disorders or other trauma symptomology, there is unease. Whether or not students recognize what is happening to them, something is happening inside of them. And those adults within the college (not the new students who are adults of which there are a growing number) are often unaware of or unable to recognize trauma symptomology. They attribute what they see to a myriad of other factors, including that the quality of students is declining with the need to have better high school preparation and the decline of values in a generation. Perhaps the students are too “snowflaky” and their parents too involved.

One shooting, many consequences for students

The students in Santa Clarita have been traumatized by the shooting; the impact of the shooting on each student will differ depending on their background in terms of family stability and family dysfunction, prior trauma from other events including death, illness, accidents and injuries. The degree of closeness to the deceased and injured and the shooter are all issues that will affect these students. How the trauma and its symptoms are handled by their school and within their community are issues too, particularly when the school reopens and the details of the events are disclosed.

And anniversaries will occur and recur. Those are inevitabilities.

I worry a lot about those students who will head off to college soon, whether from Santa Clarita or elsewhere. Will this tragedy change where they apply? Will it change how they feel about leaving home? And once they choose a school, how easy will it be to adjust? Do they need a year off to work and reflect and process? Will they feel safe in a new place and space? Will they feel cared about by some adult? Will they have an outlet in which to share how the memories of the shooting keep flooding back at different times of day and night? Will they want a seat at orientation near a door? Will they want a dorm room on a high floor or a low floor?

Then, consider these possible other reactions of the survivors. Will they not want to attend classes in the morning (around the time of the shooting)? Where will they sit in the classroom? Will they be looking for exits? How will they respond to dorm alarms and other loud sounds and future drills? Will these survivors be able to manage stress? What if a student on their new campus is injured or killed or becomes ill? When the shooting occurred, what were they doing actually and can they do whatever that was again? Will a quadrangle ever feel totally safe?

As to the elementary school students, they will proceed through the educational pipeline and hopefully, many will land in colleges at some point in the next decade or so. They will not have forgotten the shooting or if they have, they have only forgotten it in their conscious memory. What has happened to them in the decade between the shooting and entering college? Any more trauma? Yes, of course. There will be other school shootings and deaths and injuries and car accidents.

Our trauma suitcases travel with us

Here’s the point: The school shooting will eventually land on college campuses in the invisible backpacks of students. Regrettably, most colleges are not trauma-informed nor trauma-responsive. And folks will be shocked when these students struggle or barely stay in school or drop out or stop out. Their learning, their memories, their engagement can all be impacted.

It’s time to see the trauma around us and how it affects education. And we need educators who can and will be ready, willing and able to be trauma-responsive at the university level. Are you confident that will happen? I’m not. That’s why this shooting makes the need to address trauma across the educational pipeline not a luxury, but a necessity.

The time to start is now.

Karen Gross is former president of Southern Vermont College and senior policy adviser to the U.S. Department of Education. She specializes in student success and trauma across the educational landscape. Her new book, Educating for Trauma, will be released in June 2020 by Columbia Teachers College Press.