Vox clamantis in deserto

Germán Reyes: Don’t panic about college students’ use of AI

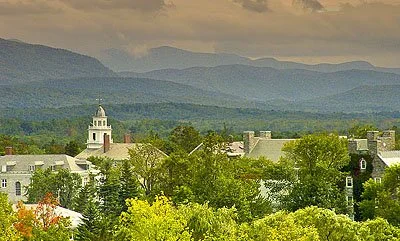

Tower of Old Chapel of Middlebury College, with the Green Mountains in the distance.

— Photo by Dogstarsail

From The Conversation Web site, except for photo above

Germán Reyes is an assistant professor of economics at Middlebury College

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

MIDDLEBURY, Vt.

More than 80% of students at Middlebury College, which is considered elite, use generative artificial intelligence for coursework, according to a recent survey I conducted with my colleague and fellow economist Zara Contractor. This is one of the fastest technology- adoption rates on record, far outpacing the 40% adoption rate among U.S. adults, and it happened in less than two years after ChatGPT’s public launch.

Although we surveyed only one college, our results align with similar studies, providing an emerging picture of the technology’s use in higher education.

Between December 2024 and February 2025, we surveyed over 20% of Middlebury College’s student body, or 634 students, to better understand how students are using artificial intelligence, and published our results in a working paper that has not yet gone through peer review.

What we found challenges the panic-driven narrative around AI in higher education and instead suggests that institutional policy should focus on how AI is used, not whether it should be banned.

Contrary to alarming headlines suggesting that “ChatGPT has unraveled the entire academic project” and “AI Cheating Is Getting Worse,” we discovered that students primarily use AI to enhance their learning rather than to avoid work.

When we asked students about 10 different academic uses of AI – from explaining concepts and summarizing readings to proofreading, creating programming code and, yes, even writing essays – explaining concepts topped the list. Students frequently described AI as an “on-demand tutor,” a resource that was particularly valuable when office hours weren’t available or when they needed immediate help late at night.

We grouped AI uses into two types: “augmentation” to describe uses that enhance learning, and “automation” for uses that produce work with minimal effort. We found that 61% of the students who use AI employ these tools for augmentation purposes, while 42% use them for automation tasks like writing essays or generating code.

Even when students used AI to automate tasks, they showed judgment. In open-ended responses, students told us that when they did automate work, it was often during crunch periods like exam week, or for low-stakes tasks like formatting bibliographies and drafting routine emails, not as their default approach to completing meaningful coursework.

Of course, Middlebury is a small liberal-arts college with a relatively large portion of wealthy students. What about everywhere else? To find out, we analyzed data from other researchers covering over 130 universities across more than 50 countries. The results mirror our Middlebury findings: Globally, students who use AI tend to be more likely to use it to augment their coursework, rather than automate it.

But should we trust what students tell us about how they use AI? An obvious concern with survey data is that students might underreport uses they see as inappropriate, like essay writing, while overreporting legitimate uses like getting explanations. To verify our findings, we compared them with data from AI company Anthropic, which analyzed actual usage patterns from university email addresses of their chatbot, Claude AI.

Anthropic’s data shows that “technical explanations” represent a major use, matching our finding that students most often use AI to explain concepts.

Similarly, Anthropic found that designing practice questions, editing essays and summarizing materials account for a substantial share of student usage, which aligns with our results.

In other words, our self-reported survey data matches actual AI conversation logs.

Why it matters

As writer and academic Hua Hsu recently noted, “There are no reliable figures for how many American students use A.I., just stories about how everyone is doing it.” These stories tend to emphasize extreme examples, like a Columbia student who used AI “to cheat on nearly every assignment.”

But these anecdotes can conflate widespread adoption with universal cheating. Our data confirms that AI use is indeed widespread, but students primarily use it to enhance learning, not replace it. This distinction matters: By painting all AI use as cheating, alarmist coverage may normalize academic dishonesty, making responsible students feel naive for following rules when they believe “everyone else is doing it.”

Moreover, this distorted picture provides biased information to university administrators, who need accurate data about actual student AI usage patterns to craft effective, evidence-based policies.

What’s next

Our findings suggest that such extreme policies a blanket bans or unrestricted use carry risks.

Prohibitions may disproportionately harm students who benefit most from AI’s tutoring functions while creating unfair advantages for rule breakers. But unrestricted use could enable harmful automation practices that may undermine learning.

Instead of one-size-fits-all policies, our findings lead me to believe that institutions should focus on helping students distinguish beneficial AI uses from potentially harmful ones. Unfortunately, research on AI’s actual learning impacts remains in its infancy – no studies I’m aware of have systematically tested how different types of AI use affect student learning outcomes, or whether AI impacts might be positive for some students but negative for others.

Until that evidence is available, everyone interested in how this technology is changing education must use their best judgment to determine how AI can foster learning.

James L. Fitzsimmons: Of hurricanes and Huracan

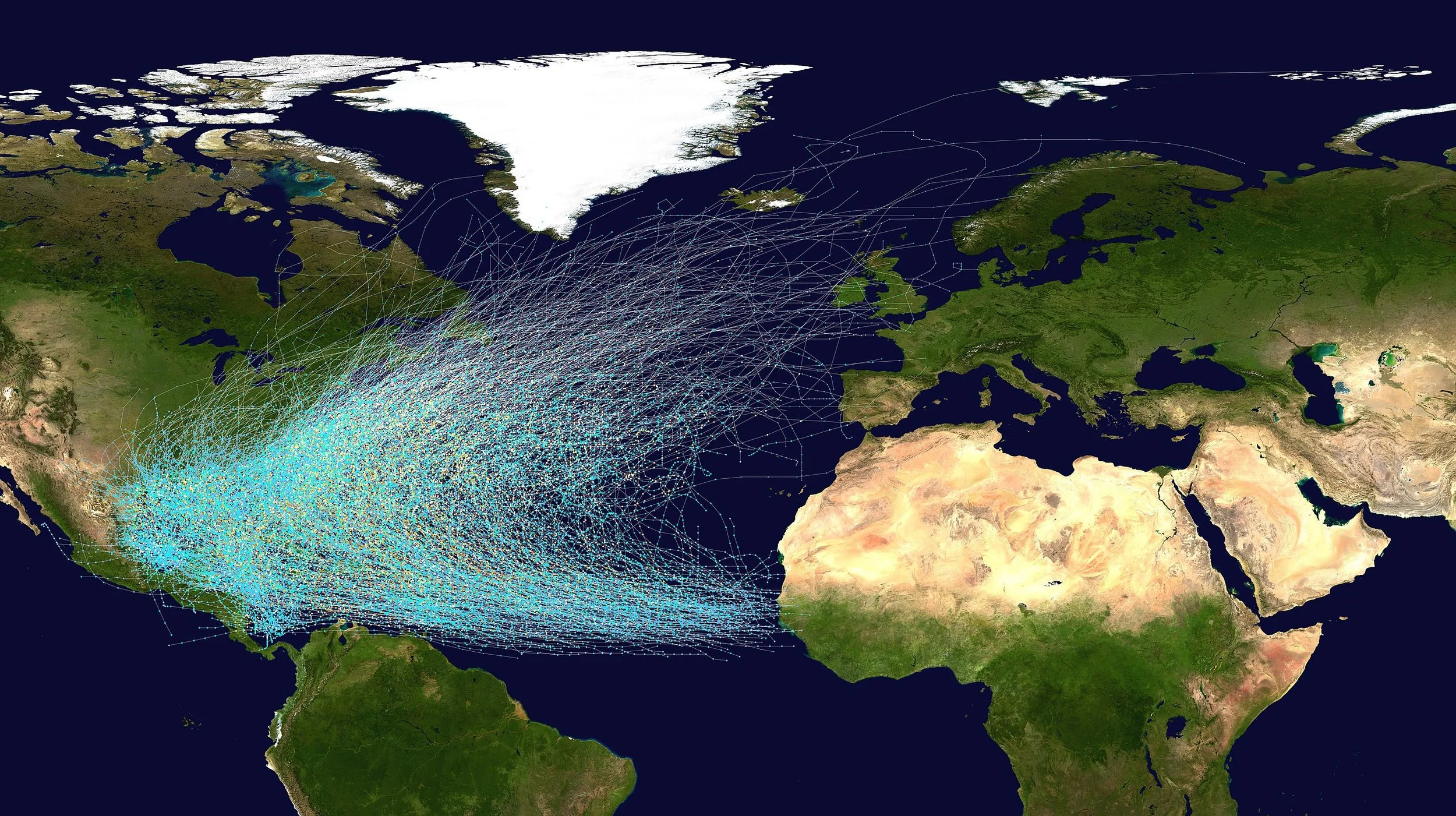

Tracks of North Atlantic tropical cyclones 1851-2019

MIDDLEBURY, Vt.

The ancient Maya believed that everything in the universe, from the natural world to everyday experiences, was part of a single, powerful spiritual force. They were not polytheists who worshipped distinct gods but pantheists who believed that various gods were just manifestations of that force.

Some of the best evidence for this comes from the behavior of two of the most powerful beings of the Maya world: The first is a creator god whose name is still spoken by millions of people every fall – Huracán, or “Hurricane.” The second is a god of lightning, K'awiil, from the early first millennium C.E.

As a scholar of the Indigenous religions of the Americas, I recognize that these beings, though separated by over 1,000 years, are related and can teach us something about our relationship to the natural world.

Huracán, the ‘Heart of Sky’

Huracán was once a god of the K’iche’, one of the Maya peoples who today live in the southern highlands of Guatemala. He was one of the main characters of the Popol Vuh, a religious text from the 16th century. His name probably originated in the Caribbean, where other cultures used it to describe the destructive power of storms.

The K’iche’ associated Huracán, which means “one leg” in the K’iche’ language, with weather. He was also their primary god of creation and was responsible for all life on earth, including humans.

Because of this, he was sometimes known as U K'ux K'aj, or “Heart of Sky.” In the K'iche’ language, k'ux was not only the heart but also the spark of life, the source of all thought and imagination.

Yet, Huracán was not perfect. He made mistakes and occasionally destroyed his creations. He was also a jealous god who damaged humans so they would not be his equal. In one such episode, he is believed to have clouded their vision, thus preventing them from being able to see the universe as he saw it.

Huracán was one being who existed as three distinct persons: Thunderbolt Huracán, Youngest Thunderbolt and Sudden Thunderbolt. Each of them embodied different types of lightning, ranging from enormous bolts to small or sudden flashes of light.

Despite the fact that he was a god of lightning, there were no strict boundaries between his powers and the powers of other gods. Any of them might wield lightning, or create humanity, or destroy the Earth.

Another storm god

The Popol Vuh implies that gods could mix and match their powers at will, but other religious texts are more explicit. One thousand years before the Popol Vuh was written, there was a different version of Huracán called K'awiil. During the first millennium, people from southern Mexico to western Honduras venerated him as a god of agriculture, lightning and royalty.

The ancient Maya god K'awiil, left, had an ax or torch in his forehead as well as a snake in place of his right leg. K5164 from the Justin Kerr Maya archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C., CC BY-SA

Illustrations of K'awiil can be found everywhere on Maya pottery and sculpture. He is almost human in many depictions: He has two arms, two legs and a head. But his forehead is the spark of life – and so it usually has something that produces sparks sticking out of it, such as a flint ax or a flaming torch. And one of his legs does not end in a foot. In its place is a snake with an open mouth, from which another being often emerges.

Indeed, rulers, and even gods, once performed ceremonies to K'awiil in order to try and summon other supernatural beings. As personified lightning, he was believed to create portals to other worlds, through which ancestors and gods might travel.

Representation of power

For the ancient Maya, lightning was raw power. It was basic to all creation and destruction. Because of this, the ancient Maya carved and painted many images of K'awiil. Scribes wrote about him as a kind of energy – as a god with “many faces,” or even as part of a triad similar to Huracán.

He was everywhere in ancient Maya art. But he was also never the focus. As raw power, he was used by others to achieve their ends.

Rain gods, for example, wielded him like an ax, creating sparks in seeds for agriculture. Conjurers summoned him, but mostly because they believed he could help them communicate with other creatures from other worlds. Rulers even carried scepters fashioned in his image during dances and processions.

Moreover, Maya artists always had K'awiil doing something or being used to make something happen. They believed that power was something you did, not something you had. Like a bolt of lightning, power was always shifting, always in motion.

An interdependent world

Because of this, the ancient Maya thought that reality was not static but ever-changing. There were no strict boundaries between space and time, the forces of nature or the animate and inanimate worlds.

Residents wade through a street flooded by Hurricane Helene, in Batabano, Mayabeque province, Cuba, on Sept. 26, 2024. AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa

Everything was malleable and interdependent. Theoretically, anything could become anything else – and everything was potentially a living being. Rulers could ritually turn themselves into gods. Sculptures could be hacked to death. Even natural features such as mountains were believed to be alive.

These ideas – common in pantheist societies – persist today in some communities in the Americas.

They were once mainstream, however, and were a part of K'iche’ religion 1,000 years later, in the time of Huracán. One of the lessons of the Popol Vuh, told during the episode where Huracán clouds human vision, is that the human perception of reality is an illusion.

The illusion is not that different things exist. Rather it is that they exist independent from one another. Huracán, in this sense, damaged himself by damaging his creations.

Hurricane season every year should remind us that human beings are not independent from nature but part of it. And like Hurácan, when we damage nature we damage ourselves.

James L. Fitzsimmons is a professor of anthropology at Middlebury College.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Erik Bleich and Christopher Star: 'Apocalypse' has become a secular term, too

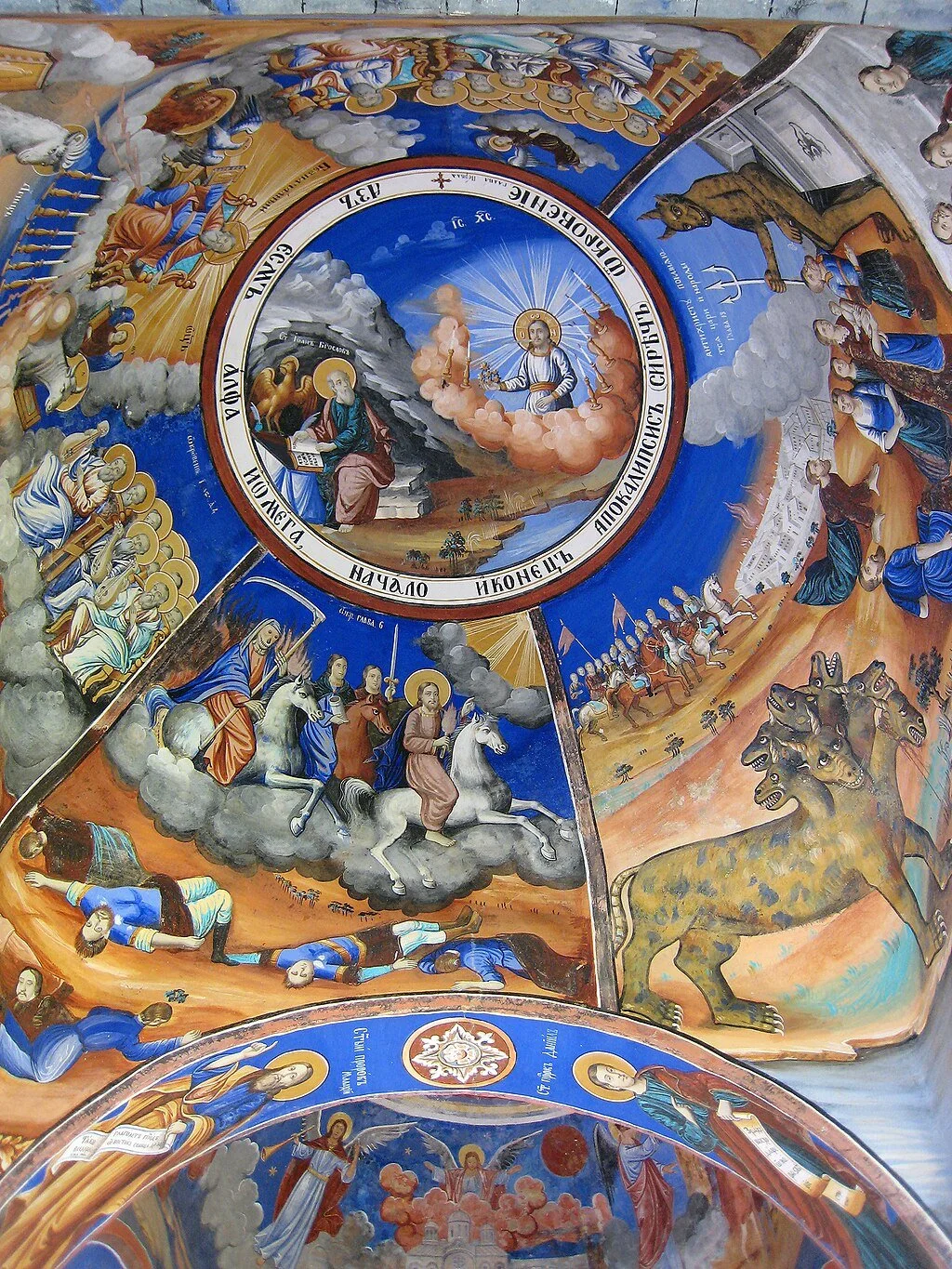

Apocalypse depicted in Christian Orthodox traditional fresco scenes in Osogovo Monastery, North Macedonia

From The Conversation

MIDDLEBURY, VT.

The exponential growth of artificial intelligence over the past year has sparked discussions about whether the era of human domination of our planet is drawing to a close. The most dire predictions claim that the machines will take over within five to 10 years.

Fears of AI are not the only things driving public concern about the end of the world. Climate change and pandemic diseases are also well-known threats. Reporting on these challenges and dubbing them a potential “apocalypse” has become common in the media – so common, in fact, that it might go unnoticed, or may simply be written off as hyperbole.

Is the use of the word “apocalypse” in the media significant? Our common interest in how the American public understands apocalyptic threats brought us together to answer this question. One of us is a scholar of the apocalypse in the ancient world, and the other studies press coverage of contemporary concerns.

By tracing what events the media describe as “apocalyptic,” we can gain insight into our changing fears about potential catastrophes. We have found that discussions of the apocalypse unite the ancient and modern, the religious and secular, and the revelatory and the rational. They show how a term with roots in classical Greece and early Christianity helps us articulate our deepest anxieties today.

What is an apocalypse?

Humans have been fascinated by the demise of the world since ancient times. However, the word apocalypse was not intended to convey this preoccupation. In Greek, the verb “apokalyptein” originally meant simply to uncover, or to reveal.

In his dialogue “Protagoras,” Plato used this term to describe how a doctor may ask a patient to uncover his body for a medical exam. He also used it metaphorically when he asked an interlocutor to reveal his thoughts.

A wood engraving by German painter Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld illustrates a scene from the Book of Revelation. ZU_09/DigitalVision Vectors via Getty images

New Testament authors used the noun “apokalypsis” to refer to the “revelation” of God’s divine plan for the world. In the original Koine Greek version, “apokalypsis” is the first word of the Book of Revelation, which describes not only the impending arrival of a painful inferno for sinners, but also a second coming of Christ that will bring eternal salvation for the faithful.

The apocalypse in the contemporary world

Many American Christians today feel that the day of God’s judgment is just around the corner. In a December 2022 Pew Research Center Survey, 39% of those polled believed they were “living in the end times,” while 10% said that Jesus will “definitely” or “probably” return in their lifetime.

Yet for some believers, the Christian apocalypse is not viewed entirely negatively. Rather, it is a moment that will elevate the righteous and cleanse the world of sinners.

Secular understandings of the word, by contrast, rarely include this redeeming element. An apocalypse is more commonly understood as a cataclysmic, catastrophic event that will irreparably alter our world for the worse. It is something to avoid, not something to await.

What we fear most, decade by decade

Political communications scholars Christopher Wlezien and Stuart Soroka demonstrate in their research that the media are likely to reflect public opinion even more than they direct it or alter it. While their study focused largely on Americans’ views of important policy decisions, their findings, they argue, apply beyond those domains.

If they are correct, we can use discussions of the apocalypse in the media over the past few decades as a barometer of prevailing public concerns.

Following this logic, we collected all articles mentioning the words “apocalypse” or “apocalyptic” from The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post between Jan. 1, 1980, and Dec. 31, 2023. After filtering out articles centered on religion and entertainment, there were 9,380 articles that mentioned one or more of four prominent apocalyptic concerns: nuclear war, disease, climate change and AI.

Through the end of the Cold War, fears of nuclear apocalypse predominated not only in the newspaper data we assembled, but also in visual media such as the 1983 post-apocalyptic film The Day After, which was watched by as many as 100 million Americans.

By the 1990s, however, articles linking the word apocalypse to climate and disease – in roughly equal measure – had surpassed those focused on nuclear war. By the 2000s, and even more so during the 2010s, newspaper attention had turned squarely in the direction of environmental concerns.

The 2020s disrupted this pattern. COVID-19 caused a spike in articles mentioning the pandemic. There were almost three times as many stories linking disease to the apocalypse in the first four years of this decade compared to the entire 2010s.

In addition, while AI was practically absent from media coverage through 2015, recent technological breakthroughs generated more apocalypse articles touching on AI than on nuclear concerns in 2023 for the first time ever.

What should we fear most?

Do the apocalyptic fears we read about most actually pose the greatest danger to humanity? Some journalists have recently issued warnings that a nuclear war is more plausible than we realize.

That jibes with the perspective of scientists responsible for the Doomsday Clock who track what they think of as the critical threats to human existence. They focus principally on nuclear concerns, followed by climate, biological threats and AI.

It might appear that the use of apocalyptic language to describe these challenges represents an increasing secularization of the concept. For example, the philosopher Giorgio Agamben has argued that the media’s portrayal of COVID-19 as a potentially apocalyptic event reflects the replacement of religion by science. Similarly, the cultural historian Eva Horn has asserted that the contemporary vision of the end of the world is an apocalypse without God.

However, as the Pew poll demonstrates, apocalyptic thinking remains common among American Christians.

The key point is that both religious and secular views of the end of the world make use of the same word. The meaning of “apocalypse” has thus expanded in recent decades from an exclusively religious idea to include other, more human-driven apocalyptic scenarios, such as a “nuclear apocalypse,” a “climate apocalypse,” a “COVID-19 apocalypse” or an “AI apocalypse.”

In short, the reporting of apocalypses in the media does indeed provide a revelation – not of how the world will end but of the ever-increasing ways in which it could end. It also reveals a paradox: that people today often envision the future most vividly when they revive and adapt an ancient word.

Erik Bleich is Charles A. Dana Professor of Political Science, and Christopher Star a professor of classics, at Middlebury College.

These authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Tools of old-fashioned daily work

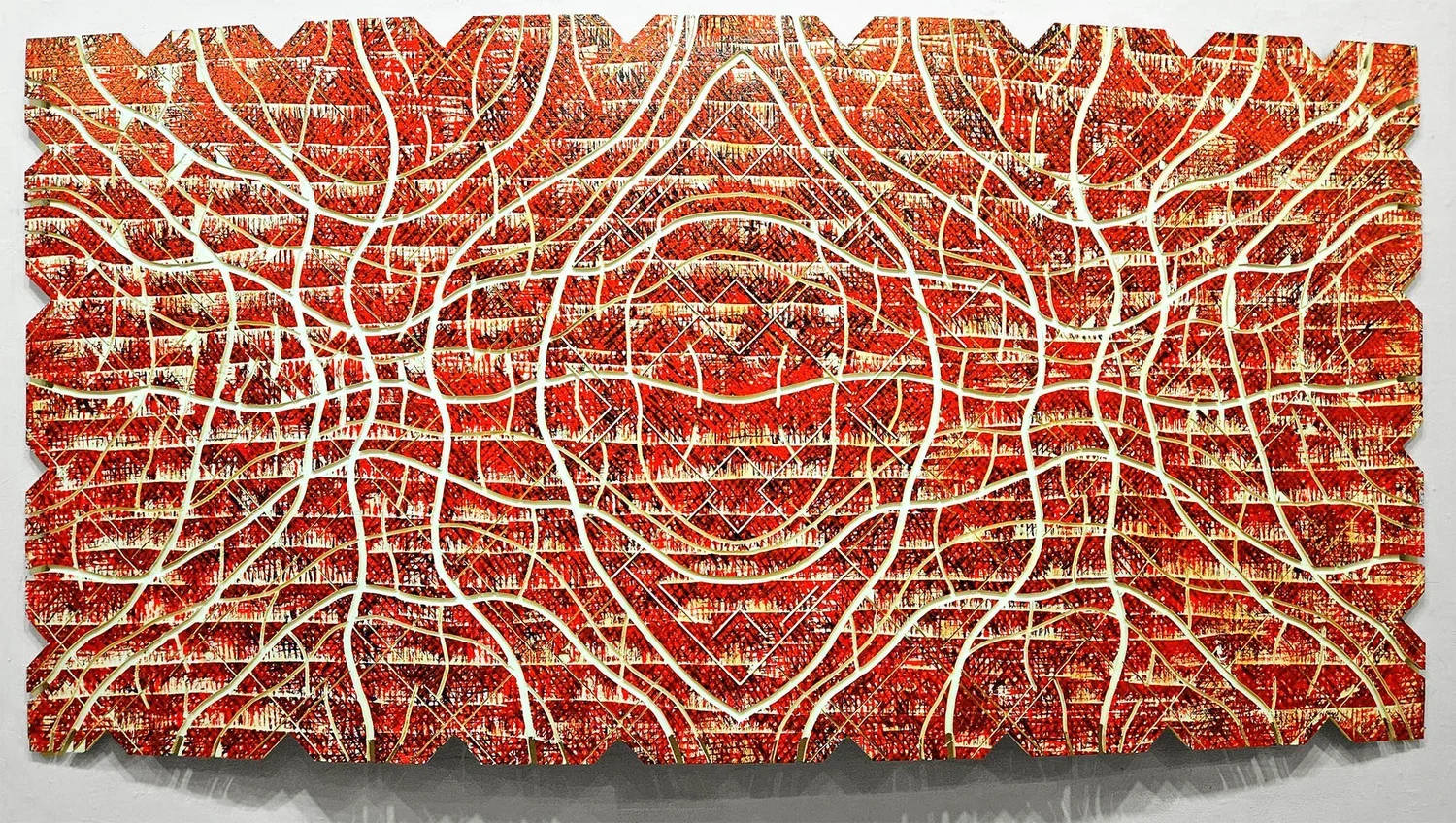

“Intimations” (oil on linen) by Middlebury, Vt.-based painter Kate Gridley, at Edgewater Gallery, in Middlebury. Her Web site says:

“Known for her insights into human character, the quality of light in her work, and her painting technique, Kate Gridley maintains a studio in Middlebury, Vermont, where she has lived and painted full time since 1991.’’

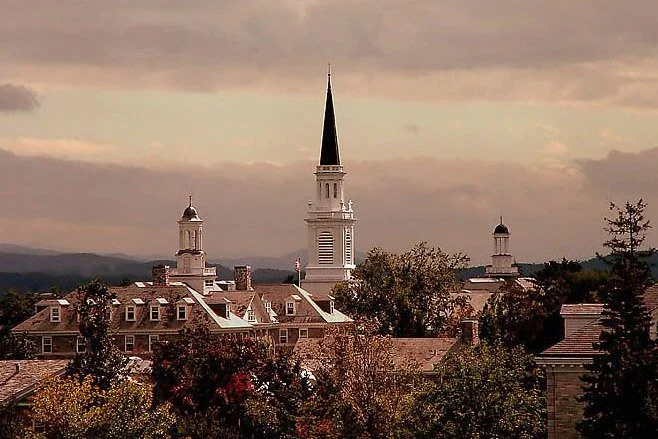

At Middlebury College, with the Green Mountains in the background

Animals in Middlebury

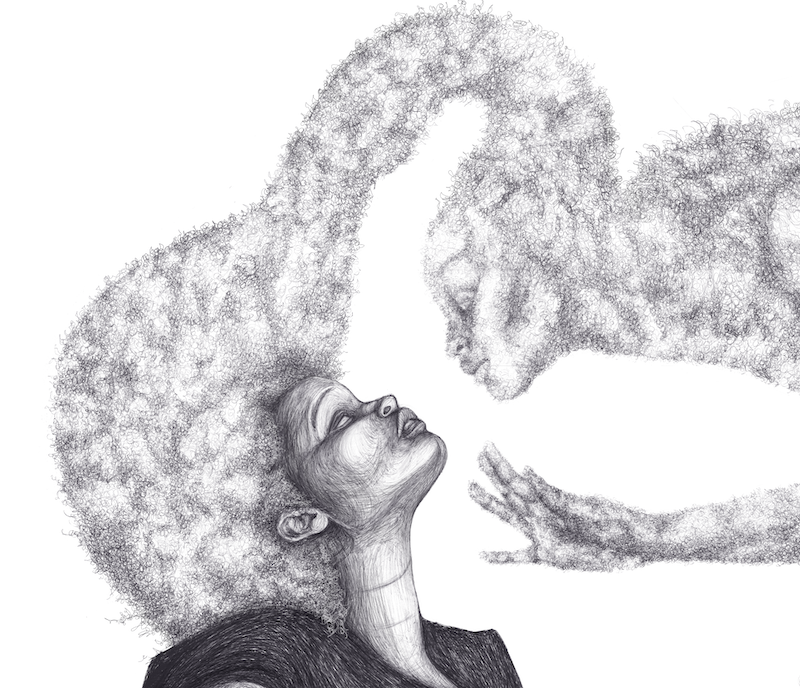

“The Messenger,’’ by Dana Simson, in her show “the animals are innocent,’’ at the Henry Sheldon Museum, Middlebury, Vt., through Jan. 11.

The museum says that the exhibit features the mixed-media work of artist, ceramist, author and illustrator Simson. “Her ceramic boat sculptures with their animal passengers, along with her paintings of animals, appear whimsical and charming at first glance. However, there's a more serious side to the works, as they're meant to represent the potential effects of climate change on animals.’’

Middlebury is best known as the home of Middlebury College and, especially for the college’s Bread Loaf School of English, a graduate school associated with many celebrated writers, but especially the great poet Robert Frost, who lived part of the year in nearby Ripton, Vt. , in a homestead now owned by MIddlebury College. The area also has many beautiful and highly productive farms. The Green Mountains rise to the east of Middlebury.

Middlebury College, which is considered elite

Downtown Middlebury

Lithograph of Middlebury from 1886 by L.R. Burleigh with list of landmarks