Vox clamantis in deserto

Ticked off over preauthorization

Rash from Lyme disease after a tick bite.

Androscoggin River, in Brunswick, Maine, with Free Black Railroad Bridge in the foreground.

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (KFF Health News), except for image above

Leah Kovitch was pulling invasive plants in the meadow near her home in Brunswick, Maine, one weekend in late April when a tick latched onto her leg.

She didn’t notice the tiny bug until Monday, when her calf muscle began to feel sore. She made an appointment that morning with a telehealth doctor — one recommended by her health-insurance plan — which prescribed a 10-day course of doxycycline to prevent Lyme disease and strongly suggested she be seen in person. So, later that day, she went to a walk-in clinic near her home in Brunswick, Maine.

And it’s a good thing she did. Clinic staffers found another tick on her body during the same visit. Not only that, one of the ticks tested positive for Lyme, a bacterial infection that, if untreated, can cause serious conditions affecting the nervous system, heart and joints. Clinicians prescribed a stronger, single dose of the prescription medication.

“I could have gotten really ill,” Kovitch said.

But Kovitch’s insurer denied coverage for the walk-in visit. Its reason? She hadn’t obtained a referral or preapproval for it. “Your plan doesn’t cover this type of care without it, so we denied this charge,” a document from her insurance company explained.

Health insurers have long argued that prior authorization — when health plans require approval from an insurer before someone receives treatment — reduces waste and fraud, as well as potential harm to patients. And while insurance denials are often associated with high-cost care, such as cancer treatment, Kovitch’s tiny tick bite exposes how prior authorization policies can apply to treatments that are considered inexpensive and medically necessary.

The Trump administration announced this summer that dozens of private health insurers agreed to make sweeping changes to the prior-authorization process. The pledge includes releasing certain medical services from prior-authorization requirements altogether. Insurers also agreed to extend a grace period to patients who switch health plans, so that they won’t immediately encounter new preapproval rules that disrupt ongoing treatment.

Mehmet Oz, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, said during a June press conference that some of the changes would be in place by January. But, so far, the federal government has offered few specifics about which diagnostic codes tagged to medical services for billing purposes will be exempt from prior authorization — or how private companies will be held accountable. It’s not clear whether Lyme disease cases like Kovitch’s would be exempt from preauthorization.

5 Takeaways From Health Insurers’ New Pledge To Improve Prior Authorization

Dozens of health insurance companies recently pledged to improve prior authorization, a process often used to deny care. The announcement comes months after the killing of UnitedHealthcare chief executive Brian Thompson, whose death in December sparked widespread criticism about insurance denials.

Chris Bond, a spokesperson for AHIP, the health- insurance industry’s main trade group, said that insurers have committed to implementing some changes by Jan. 1. Other parts of the pledge will take longer. For example, insurers agreed to answer 80% of prior authorization approvals in “real time,” but not until 2027.

Andrew Nixon, a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, told KFF Health News that the changes promised by private insurers are intended to “cut red tape, accelerate care decisions, and encourage transparency,” but they will “take time to achieve their full effect.”

Meanwhile, some health-policy experts are skeptical that private insurers will make good on the pledge. This isn’t the first time major health insurers have vowed to reform prior authorization.

Bobby Mukkamala, president of the American Medical Association, wrote in July that the promises made by health insurers in June to fix the system are “nearly identical” to those the insurance industry put forth in 2018.

“I think this is a scam,” said Neal Shah, author of the book “Insured to Death: How Health Insurance Screws Over Americans — And How We Take It Back.”

Insurers signed on to President Trump’s pledge to ease public pressure, Shah said. Collective outrage directed at insurance companies was particularly intense following the killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in December. Oz specifically said that the pledge by health insurers was made in response to “violence in the streets.”

Shah, for one, doesn’t believe that companies will follow through in a meaningful way.

“The denials problem is getting worse,” said Shah, who co-founded Counterforce Health, a company that helps patients appeal insurance denials by using artificial intelligence. “There’s no accountability.”

Cracking the Case

Kovitch’s bill for her clinic appointment was $238, and she paid for it out-of-pocket after learning that her insurance company, Anthem, didn’t plan to cover a cent. First, she tried appealing the denial. She even obtained a retroactive referral from her primary-care doctor supporting the necessity of the clinic visit.

It didn’t work. Anthem again denied coverage for the visit. When Kovitch called to learn why, she said she was left with the impression that the Anthem representative she spoke to couldn’t figure it out.

“It was like over their heads or something,” Kovitch said. “This was all they would say, over and over again: that it lacked prior authorization.”

Jim Turner, a spokesperson for Anthem, later attributed Kovitch’s denials to “a billing error” made by MaineHealth, the health system that operates the walk-in clinic where she sought care. MaineHealth’s error “resulted in the claim being processed as a specialist visit instead of a walk-in center/urgent care visit,” Turner told KFF Health News.

He did not provide documentation demonstrating how the billing error occurred. Medical records supplied by Kovitch show that MaineHealth coded her walk-in visit as “tick bite of left lower leg, initial encounter,” and it’s not clear why Anthem interpreted that as a specialist visit.

After KFF Health News contacted Anthem with questions about Kovitch’s bill, Turner said that the company “should have identified the billing error sooner in the process than we did and we apologize for the confusion this caused Ms. Kovitch.”

Caroline Cornish, a spokesperson for MaineHealth, said this isn’t the only time that Anthem has denied coverage for patients seeking walk-in or urgent care at MaineHealth. She said Anthem’s processing rules are sometimes misapplied to walk-in visits, leading to “inappropriate denials.”

She said that these visits should not require prior authorization and Kovitch’s case illustrates how insurance companies often use administrative denials as a first response.

“MaineHealth believes insurers should focus on paying for the care their members need, rather than creating obstacles that delay coverage and risk discouraging patients from seeking care,” she said. “The system is too often tilted against the very people it is meant to serve.”

Meanwhile, in October, Anthem sent Kovitch an updated explanation of benefits showing that a combination of insurance-company payments and discounts would cover the entire cost of the appointment. She said that a company representative called her and apologized. In early November, she received her $238 refund.

But she recently found out that her annual eye appointment now requires a referral from her primary-care provider, according to new rules laid out by Anthem.

“The trend continues,” she said. “Now I am more savvy to their ways.”

Lauren Sausser is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter ( lsausser@kff.org, @laurenmsausser)

Pfizer to conduct Lyme disease vaccine test in Maine

Deer ticks are the major spreaders of Lyme disease.

The Emerson Cemetery in Lyme. Wear long socks!

Edited from a report by The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Pfizer has partnered with a Maine health care system to conduct the third phase of a Lyme disease clinical trial to test the efficacy of the company’s vaccine. Pfizer, a leading biomedical company, has chosen to work with Valneva, a French specialty vaccine company.

(Lyme disease gets its name from the coastal town in Connecticut where symptoms of the disease were documented and studied by Yale researchers in the 1970s. )

“The trial, held at Northern Light Health system in Brewer, will span over 13 months and require patients to take two shots two months apart. In March, the patients will need to receive a booster shot before the next summer’s tick season. Pfizer, and Valneva, choose to approach the Northern Light Health system during the clinical trial due to Maine having one of the highest rates of Lyme disease in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Kathrin U. Jansen, Ph.D., senior vice president and head of vaccine research & development at Pfizer, said, ‘{T}he medical need for vaccination against Lyme disease is steadily increasing as the geographic footprint of the disease widens. These positive pediatric data mark an important step forward in the ongoing development of VLA15, and we are excited to continue working with Valneva to potentially help protect both adults and children from Lyme disease.”’

Wilson Street, Brewer, Maine. Lyme disease has been relentlessly moving north with the warming climate. The city was once well known for brick-making, shipbuilding and paper-making.

— Photo by P199

Roger Warburton: What lobsters tell us about climate change

If present trends continue, by the end of the century, the cost of global warming could be as high as $1 billion annually for Providence County, R.I., alone, according to data from a 2017 research paper. That’s about $1,600 per person per year. Every year.

But, before we talk about the future, let’s discuss the economic damage that has already occurred in Rhode Island because of warming temperatures.

Like rich Bostonians, Rhode Island’s lobsters have moved to Maine. In 2018, Maine landed 121 million pounds of lobsters, valued at more than $491 million, and up 11 million pounds from 2017. It wasn’t always so.

Andrew Pershing, an oceanographer with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, has noted that lobsters have migrated north as climate change warms the ocean. In Rhode Island, for instance, days when the water temperature of Narragansett Bay is 80 degrees or higher are becoming more common. From 1960 to 2015, the bay’s mean surface water temperatures rose by about 3 degrees Fahrenheit, according to research data.

A 2018 research paper Pershing co-authored said ocean temperatures have risen to levels that are favorable for lobsters off northern New England and Canada but inhospitable for them in southern New England. The research found that warming waters, ecosystem changes, and differences in conservation efforts led to the simultaneous collapse of the lobster fishery in southern New England and record-breaking landings in the Gulf of Maine.

He told Science News last year that with rocky bottoms, kelp and other things that lobsters love, climate change has turned the Gulf of Maine into a “paradise for lobsters.”

However, in the formerly strong lobster fishing grounds of Rhode Island, the situation is grim. South of Cape Cod, the lobster catch fell from a peak of about 22 million pounds in 1997 to about 3.3 million pounds in 2013, according to the 2018 paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Lobsters provide interesting lessons on the impact of the climate crisis.

A conservation program called V-notching helped protect Maine’s lobster population. “Starting a similar conservation program earlier in southern New England would have helped insulate them from the hot water they’ve experienced over the last couple of decades,” Malin Pinsky, a marine scientist with Rutgers University, told Boston.com two years ago.

Rhode Island’s lack of conservation efforts in the face of the growing climate crisis contributed to the collapse of its lobster fishery. Doing nothing or too little in the face of a changing climate can be economically devastating.

Another existing, and growing, threat to the economic health of Rhode Island comes from Lyme disease, which has increased by more than 300 percent across the Northeast since 2001. A changing climate is a big reason why. There is a growing body of evidence showing that climate change may affect the incidence and prevalence of certain vector-borne diseases such as Lyme disease, malaria, dengue, and West Nile fever, according to a 2018 study.

Chronic Lyme disease is more widespread and more serious than generally realized. There are some 20,000 cases annually in the Northeast and each averages about $4,400 in medical costs. Most Lyme disease patients who are diagnosed and treated early can fully recover. But, an estimated 10 percent to 20 percent suffer from chronically persistent and disabling symptoms. The number of such chronic cases may approach 30,000 to 60,000 annually, according to a 2018 white paper.

As the lobsters and the ticks vividly demonstrate, prevention is cheaper than cure. The longer we wait, the more painful, and expensive, the consequences will be.

The aforementioned 2017 study Estimating Economic Damage from Climate Change in the United States by world-renown economists and climate scientists projects the impact of climate change for every county in the United States. The results for Rhode Island and its neighbors are summarized in the map to the right, which depicts the estimated economic damage, in millions of dollars annually for each county in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

The data make clear that the economic damage will not be uniformly distributed. Some counties, such as Providence County, will be hit much harder than others. It also may seem that the southern counties will suffer much less. But that isn’t quite true, as graph below shows. The damage per person per year is projected to be substantial.

The total economic damage to Rhode Island, by 2080, could result in a 2 percent decline in gross domestic product (GDP). To put that in context, during the Great Recession of 2008-2010, there was only one year of GDP decline: minus 2.5 percent in 2009. By 2010, GDP had bounced back to positive growth, at 2.6 percent.

Therefore, the impact of a 2 percent hit to Rhode Island’s GDP from the climate crisis could look like the recession of 2009, only becoming permanent, continuing year after year. Also, it won’t all happen in 2080, the damage will continually get worse.

The economic damage is projected to come from more frequent and intense storms; sea-level rise; increased rainfall resulting in more flooding; higher temperatures, especially in the summer; drought that leads to lower crop yields; increased crime.

In addition, essential infrastructure will be impacted, including water supplies and water treatment facilities. Ecosystems, such as forests, rivers, lakes and wetlands, will also suffer, and that will impact human quality of life.

In the coming two weeks, we will describe how each Rhode Island county faces different levels of the above threats. As a result, each county needs to develop appropriate mitigation strategies.

The damages from the climate crisis will place major strains on public-sector budgets. However, much of the economic damage will be felt by individuals and families through poorer health, rising energy costs, increased health-care premiums, and decreased job security.

As always, prevention is cheaper, and more effective, than cure. Inaction on climate change will be the most expensive policy option.

The lobsters should teach us a valuable lesson: conservation measures based on sound scientific and economic principles could have helped mitigate losses caused by the climate crisis.

Roger Warburton, Ph.D., is a Newport ,R.I., resident. He can be reached at rdh.warburton@gmail.com.

Bad Lyme disease season on its way

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Physical distancing because of COVID-19 has caused cabin fever to reach an all-time high, and people are seeking solace in the great outdoors. And while physical distancing rules still apply outside, the Rhode Island departments of environmental management and health are hoping that people will add another practice to their outdoor excursions: keeping an eye out for ticks.

With a mild winter in which many more ticks than usual likely survived and with more people expected to be outside this year because of the pandemic, 2020 is shaping up to be a bad year for tick bites and the transmission of Lyme and other diseases, according to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM).

Rhode Island already has the fifth-highest rate of Lyme disease in the country, with 1,111 people diagnosed in 2018.

To help mitigate this problem, DEM and the Department of Health are again promoting the state’s Tick Free Rhode Island campaign.

“At a time when the COVID-19 crisis has forced us into closing state parks and campgrounds, it might seem incongruous to sound the alarm about Lyme disease,” DEM Director Janet Coit said. “Yet, Lyme is a very dangerous disease. So, all of us, whether we’re taking a walk around the block, spending time in our backyards, or going fishing, should do our best to prevent tick bites along with respecting social distancing norms.”

Here are the agencies’ three keys to tick safety:

Repel. Avoid wooded and brushy areas with high grass and leaves. If you are going to be in a wooded area, walk in the center of the trail to avoid contact with overgrown grass, brush, and leaves at the edges. Wear long pants and long sleeves. Tuck your pants into your socks. Wear light-colored clothes so you can see ticks more easily.

Check. Take a shower after you come back inside from a wooded area. Do a full-body tick check in the mirror; parents should check their kids for ticks and pay special attention to the area in and around the ears, in the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and in their hair. Keep an eye on you pets as well, as they can bring ticks into the house.

Remove. If possible, use tweezers to remove a tick; grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible and pull straight up. If you don’t have tweezers, use a tissue or gloves. Keep an eye on the tick bite spot for signs of rash, or symptoms such as fever and headache.

Most people who get Lyme disease get a rash anywhere on their body, though it may not appear until long after the tick bite. At first, the rash looks like a red circle, but as the circle gets bigger, the middle changes color and seems to clear, so the rash looks like a target bull’s-eye.

Some people don’t get a rash, but feel sick, with headaches, fever, body aches, and fatigue. Over time, they could have swelling and pain in their joints and a stiff, sore neck; or they could become forgetful or have trouble paying attention.

Deer ticks in their developmental progression

'Lame Deer' and 'culled' ones

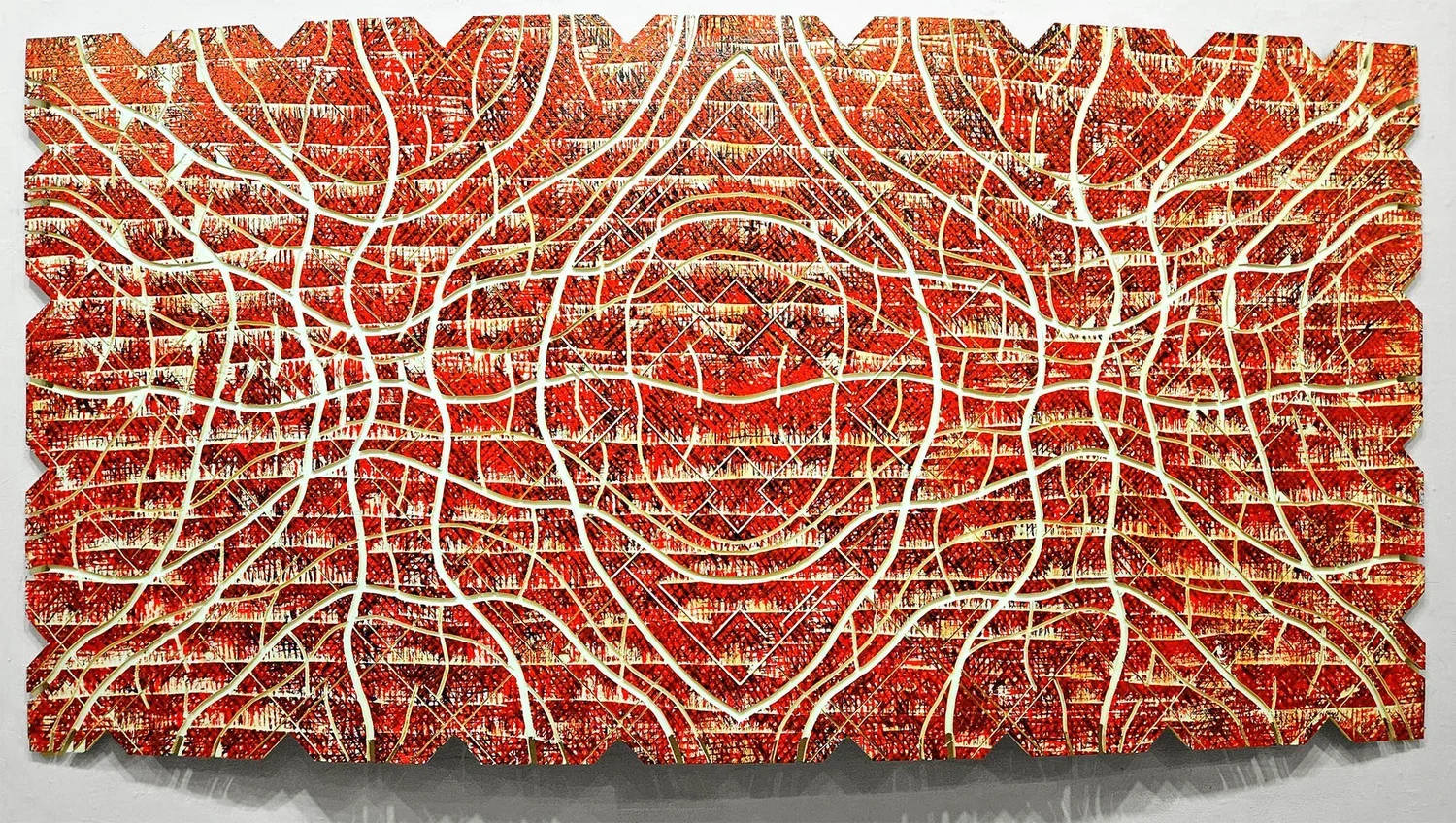

"Lame Deer (Big Eagle)'' (oil on French linen), by ROBERT S. NEUMAN, in the "Robert S. Neuman: Lame Deer Series,'' at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., Feb. 23-May 18.

Soon there will be many fewer deer on Block Island, as a Connecticut firm is being brought in to "cull'' the herd, whose population, and that of the deer ticks that carry Lyme disease, have swollen. Brutal world.