Gerald FitzGerald: My love of literature survived brutal teachers

I took beginning French five years straight and never did pass. English was a subject I actually enjoyed, but I remember three English teachers mostly for their brutality.

The first was John P. Gibney, a handsome young fellow who taught my class freshman year at the all-boys Catholic high school, Bishop Loughlin, in Brooklyn.

At Loughlin, teachers changed classrooms each period, not students. Very early on Mr. Gibney came into noisy Room 205 proclaiming: “When I enter this room, silence reigns supreme.”

A few days later, Jimmy Clarke and I were yakking between periods and we didn’t notice Mr. Gibney enter the room. He walked over to his desk on the riser and loudly let fall his books. We looked up, still standing by our seats near the front. Mr. Gibney looked at me, then at Clarke. He extended an arm toward Clarke and moved his index figure in a curling motion. Jimmy’s face dropped its smile, forming a pretty good silent version of “Sorry, sir” as he complied with the signal beckoning him closer. I slipped into my seat and hoped for the best.

It happened so quickly I cannot tell you if Mr. Gibney threw a right or a left. He connected with Jimmy’s jaw, dropping him flat out on the floor. My stomach and legs fell away in fear. Jimmy had not known what was coming whereas I now considered myself fully informed.

Jimmy slowly gained his feet and moved to behind his desk, near mine. I was owned utterly by fear as if awaiting the firing squad. But Mr. Gibney simply started the lesson. Perhaps he thought that he had gone too far, or perhaps he determined that a second assault would not be justified to prove his point. Or maybe that day I was just the luckiest kid in Brooklyn.

There was a big fellow in our class named James E. Freeman. Everyone called him by his last name only. He was very tall and muscular and had a large face and a shock of black hair. He looked just like Li’l Abner from the newspaper comic pages.

Freeman worked hard to make a favorable impression on Mr. Gibney. Seconds before class, Freeman would stack library books on his desk, such as War and Peace, works by James Joyce, poetry and plays. It was as if Freeman thought that the books would trigger Mr. Gibney’s interest, resulting in a literary conversation whereby Freeman might shine and impress. I recall that the teacher once picked up a volume but laid it right back down without stopping. I could not see if he did it with a smirk.

But, once, in the basement hall outside the cafeteria I heard the most gratuitously harsh words spoken by teacher to student. Mr. Gibney was extolling the Irish love of theater when Freeman interjected with his desire to visit Ireland one day and perhaps gain a job working at the legendary Abbey Theater, in Dublin. Mr. Gibney looked directly at Freeman, saying slowly: “Freeman, they wouldn’t let you clean the urinals at the Abbey Theater.”

None of us said another syllable. I watched the hope drain from Freeman’s face. I had neither the brains nor the heart to embrace Freeman or to take a swing at Gibney.

J.E. Freeman apparently grew up in Queens without his father and joined the Marines after high school. He served until he was 22, when he revealed his sexuality and was discharged. He claimed that he was present for the Stonewall Riots, in Greenwich Village, in 1969 and I believed him. He became a professional actor, with roles in such movies as David Lynch’s Wild at Heart, the Coen Brothers’ Miller’s Crossing, Alien Resurrection, with Sigourney Weaver, and the film Patriot Games, based on Tom Clancy’s novel with the same name. He was also kind and caring toward my eldest daughter, Megan, when she tried to break into Hollywood. He died at 68 after having been HIV-positive for 30 years and self-publishing some admirable books of his poetry.

Then there was my other English teacher at Loughlin, Brother Basilian. He was tall and fairly lean, had thinning white hair, and he was clergy -- kind of a male nun with a vertically split starched bib beneath his chin above his long black cassock, the costume of a La Salle Christian Brother.

Brother Basilian’s idea of teaching sophomore Shakespeare was to sit at his desk reading aloud all parts to Julius Caesar. I am happy to note that as a man I have avidly read, no thanks to Basilian, every word known to be written by Shakespeare, as well as many only thought to be written by The Bard.

But at the moment in question, I was utterly bored. My desk was second-to-last in the second row, as I recall. One desk ahead of me, and to my left, sat my classmate Christopher Kenney, surreptitiously reading a Superman comic held on his lap just below Brutus and the gang. In the softest whisper I could make I began to speak:

“Christopher Kenney, this is your conscience speaking.…”

Then, stretching the syllables of his name:

“Chrissss…to..pherrrr Kennn…ney, this is your conscience speaking…” Even from behind I could see Chris’s smile push up into his cheeks.

Suddenly came an unwelcome query:

“WHO IS THAAAAT?” came a wildly abrasive voice from the lips and beet-red cheeks of Bro. Basilian, He slowly rose, his eyes flaming.

Now, he was at the head of my row, swaying side-to-side, striding obsessively toward me down along the aisle.

“IS THAT YOUuuu, FitzGerald?”

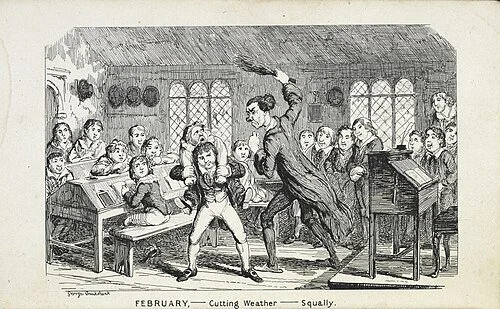

He was upon me. He slapped me where I sat, striking my left cheek with his open right hand, twisting my head and neck violently to my right, and then smashed his left hard against my right cheek to send it back. Then his right again to my left cheek, and then his left again to my right cheek. He moved to the rhythm of a butcher. He swung his right open-hand hard and fast toward my left cheek again. I moved my head backward, causing him to miss me completely; his momentum carried him face down across my desk.

Briefly, I caught sight of the frozen, open-mouthed faces of my classmates gaping at Basilian lying across my desk like a roast on a platter. I reached for the hem of his black cassock and pulled it up over his covered black trousers. Then, with a small smile, I whacked his rump in a spanking gesture. The crowd exploded! The cheers and laughter must’ve been heard throughout the entire floor of the building, if not beyond. It was, at that moment, the pinnacle of my life.

Sputtering, the brother clumsily got to his feet, picked me up with both hands and threw me several desks up the aisle. Then did the same again. I finally grabbed the handle on the classroom door and heard him tell me to report to the principal.

Eventually, Loughlin bade me farewell -– unrelated to this incident — and I entered senior year in public school.

The last of my high-school English studies was taught by a woman whose name I recall as Rose Ventresca. Hers was an Advanced Placement class and, of course, I was the new kid in a room half-filled with girls, for the first time since my eighth grade. One early class reintroduced my old pal Shakespeare. Today I take great pleasure reading his sonnets regularly with the authorial tutelage of the late Helen Vendler via her fabulous study, The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

Our homework for the day of Ms. Ventresca’s class was to briefly explicate each of two sonnets on alternate sides of a loose-leaf page. I have no memory of either sonnet.

The next day I was the first called upon to discuss The Bard’s effort. What I had written to try to explain the first sonnet was right on the money. Ms. Ventresca was thrilled. Her joy at my explication bubbled through the room. I felt enormously proud.

“Read your next explication, please,” Ms. Ventresca commanded. Eagerly, almost boldly, I leapt to fill the air with golden commentary. My eyes never left the page until I was finished reading aloud. I looked up with a broad smile and saw that Ms. Ventresca had shrunk into something vile and withered. There was only foul, frightening silence, soon broken by the brittle, sharp slicing of her teeth and tongue.

“What have you done, you cheating, monstrous fraud? From where did you steal that first, brilliant essay? You cheat! You never wrote that first explication. It’s not possible you could be so right then only to be so wrong! You copied the first one you read from some book. No one could write that and then write such a worthless take on the second sonnet.”

“I am not a cheat, I did not cheat or copy anything,” was all I could stammer back to her wholly false accusation. I have no other memory of any aspect of her class.

Poetry has helped pump my blood since my days cutting classes at Loughlin to spend hours alone wandering New York City memorizing pages of The Pocket Book of Modern Verse, listening to records in booths at the East 53rd Street public library or reading behind the stone lions at the monumental New York Public Library’s headquarters, at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street, or riding the Staten Island ferry or sneaking into the subway or hiding within The Cloisters or relaxing in my special room at the Metropolitan Museum. If it was free I spent time there with poetry. My best friend, an usher, provided a free pass to Radio City Music Hall, where I sometimes watched three consecutive shows of pretty legs and movies – but always with a book close by.

I still have my books, including a 60-cent paperback of Robert Frost’s poems given to me as my 17th birthday present by my mom shortly after the murder of President Kennedy, for whom Frost was his favorite poet.

I rarely think of my English teachers. They had very little to do with my love of literature.

Gerald FitzGerald, a Massachusetts-based writer, is a former newspaper reporter and managing editor, assistant district attorney and trial lawyer.