Fred D. Begley: How NIH became backbone of medical research and boosted U.S. innovation and economy

Bentley University Library, in Waltham, Mass.

From The Conversation, except for image above.

Fred D. Ledley is director of the Center for Integration of Science and Industry at Bentley University.

His research has been supported by grants to Bentley University from the Institute for New Economic Thinking, National Pharmaceutical Council, West Health, and the National Biomedical Research Foundation.

(Editor’s note: There are many NIH-linked facilities in New England.)

As a young medical student in 1975, I walked into a basement lab at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., to interview for a summer job.

It turned out to be the start of a lifelong affiliation – first as a trainee, then as a grantee running a university laboratory and finally, now, as a researcher of economics and public policy studying the agency’s impact on health care and on the national economy.

On that initial visit 50 years ago, I got my first direct experience with the NIH’s mission: to tap the enormous potential of basic science to improve human health and medical care. And over the long arc of my career, I watched the agency enact this mission in ways that brought enormous value to the country. NIH funding trained a legion of biomedical scientists, produced countless therapies that underpin much of modern medicine and catalyzed the launch of the biotechnology industry.

But widespread federal grant terminations and disruptions to federal funding in 2025 have left scientists who depend on NIH support reeling. And a 40% cut to the NIH budget for 2026 proposed by the White House threatens the agency’s future.

Origins and growth of the NIH

The NIH was founded through the Ransdell Act of 1930, which converted the former Hygienic Laboratory of the Marine Hospital Services into the seeds of a new government institution. That laboratory had been established in 1887 to develop public health measures, diagnostics and vaccines for controlling diseases prevalent in the U.S. at the time, such as cholera, yellow fever, smallpox, plague and diphtheria. With the act’s passage, the Hygienic Laboratory was reimagined as the National Institute of Health.

The NIH, initially called the National Institute of Health, was created in 1930 with the passage of the Ransdell Act. President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated the new NIH campus in Bethesda, Md., on Oct. 31, 1940, saying, ‘We cannot be a strong nation unless we are a healthy nation.’ National Institutes of Health

Sen. Joseph Ransdell of Louisiana envisioned the NIH as an agency with a broader mandate for translating scientific advances to improve human health. In arguing in 1929 for the creation of the new institute, he read into the Congressional Record an editorial from The New York Times that highlighted rapid advances in chemistry, physiology and physics.

The editorial lamented that “never in the whole history of the world had efforts to improve health conditions been behind the advance in other sciences.” Pointing to millions of Americans suffering from sickness leading to economic losses “into billions,” it argued for the need for a medical sciences institute coordinating “a national effort to prevent diseases that are or may be preventable.”

In 1945, a report called Science – The Endless Frontier, by Vannevar Bush, highlighted the government’s central role in supporting science that harnessed nuclear energy, implemented radar and developed penicillin – all important elements of the United States’ success in World War II. Bush argued that these wartime successes presented a model for growing the American economy, preventing and curing disease and projecting American power.

The NIH became central to this model. Its budget increased substantially during and just after World War II, with postwar adoption of Bush’s plan, and again after 1957 when the nation redoubled its commitment to science following Russia’s launch of Sputnik and the start of the space race. The National Cancer Act of 1971, which established the separate National Cancer Institute, reaffirmed the nation’s commitment to government-funded research. This new institute’s funding provided much of the seed capital for the emergence of biotechnology.

In the 1980s, the Stevenson-Wydler and Bayh-Dole acts created a clear pathway for developing commercial products from federally funded research that would provide public benefits and economic stimulus. These federal laws made it a requirement to pursue patenting and licensing of NIH-funded research to industry.

One project’s evolution reflects NIH’s mission

Today, the NIH represents the backbone of efforts to improve health and health care, supporting each step in the process from preliminary discovery to clinical advance. These steps correspond to the stages of an individual scientist’s path.

By putting study volunteers into a specially constructed metabolic chamber, NIH researchers in the 1950s could study how the human body uses air, water and food. The nurse here is affixing a hood onto a volunteer to measure oxygen consumption. National Institutes of Health

I experienced this progression in my own career. After establishing my first independent laboratory with a grant for early-stage researchers, then called a First Independent Research Support and Transition grant, a Research Project grant, widely known as an R01, funded my lab’s work identifying genes that cause inherited metabolic diseases in newborns. R01 grants are the main mechanism that academic biomedical scientists in the U.S. rely on to support innovative research.

Later, an NIH Program Project grant enabled us to investigate how the genes we had identified could be used to treat children. A General Clinical Research Center grant supported the hospital facilities necessary for clinical research and paid for patient care. Other grants supported our medical students and fellows as they embarked on their own careers as well as applications of our research to areas such as child health, reproductive biology and gastroenterology.

As our research on gene therapy progressed, NIH Small Business grants contributed to our founding a company that raised US$200 million in investments and partnerships and created hundreds of new jobs in Houston. Grants to small businesses continue to play a crucial role in helping universities commercialize discoveries.

Is the NIH effective?

For the past decade, I have led a research center focused on characterizing the process of developing new drugs. Our work, which is not funded by the NIH, shows that an established foundation of basic research on the biology underlying health and disease is necessary for successful drug development – and that most of this research is performed in public institutions.

We have found that NIH funding supported basic or applied research related to about 99% of newly approved medicines, clinical trials for 62% of these drugs and patents governing about 10% of these products.

Based on research conducted at the NIH, azidothymidine, or AZT, in 1987 became the first drug approved to treat AIDS. Here, the drug, added to the middle vial, protects healthy immune cells from being destroyed by HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. John Crawford, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health

Studies also show that this NIH funding saves industry almost $3 billion per drug in development costs. Over the past decade, there has been $800 billion in new investment in biotechnology. The U.S. biopharmaceutical industry directly supports more than 1 million jobs.

Medicines enabled by NIH funding have been crucial for increasing life expectancy and health – dramatically decreasing deaths due to heart disease and stroke, improving cancer outcomes, controlling HIV infection, improving the management of immunological diseases and easing the burden of psychiatric conditions.

The Trump administration is currently questioning the role of science in maintaining the nation’s health, economy and global posture. Yet the NIH stands as a testimony to the vision articulated by its early architects.

At its heart is the conviction that science is good for society, that persistent investment in basic research is essential to technological advances that serve the public interest, and that our nation’s health and economy benefit from developments in biology.

Before fading away

“Old Soldier” (oil on canvas), by Jean Jack, at Portland Art Gallery.

The gallery says:

“Jean Jack is a Maine-based fine artist whose iconic paintings of barns and farmhouses explore the quiet dignity of rural American architecture. Her work blends abstraction and realism, often featuring solitary structures placed within simplified landscapes that evoke a powerful emotional response. Known for capturing a distinct ‘sense of place,’ Jean’s compositions highlight the interplay between form, shadow, and space.’’

A big padded cell

Barnstable Harbor, as seen from Millway Beach.

— Photo by ToddC4176

“I had a large house {in Barnstable, Mass.} with lots of kids in it — three of my own and three adopted. And Cape Cod was a padded cell where children couldn’t possibly hurt themselves when they were growing up.’’

— Kurt Vonnegut Jr. (1922-2007), American novelist

The Goodspeed House, in Barnstable. It was built in 1653.

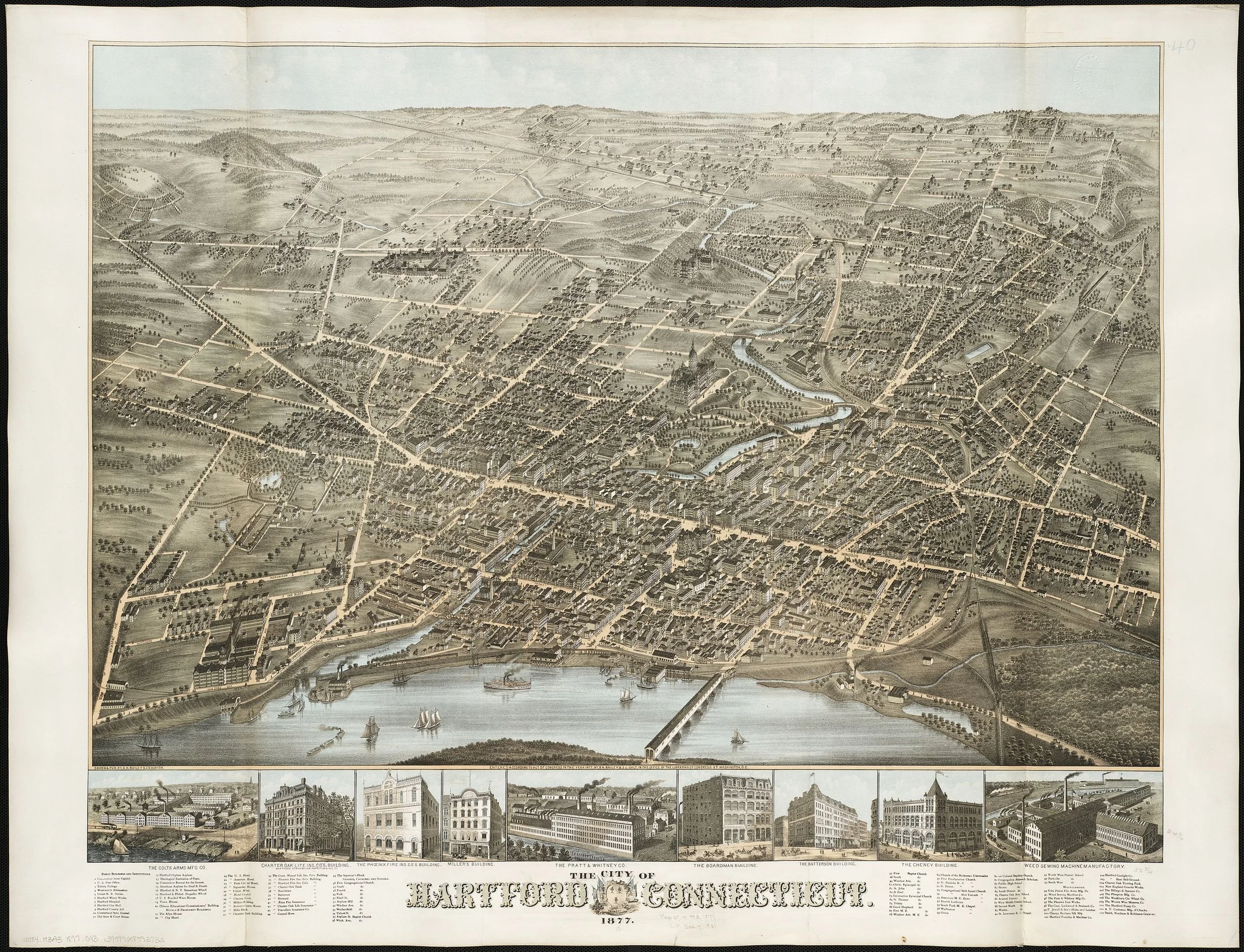

Chris Powell: In Hartford, a promising way to address the housing shortage

Hartford from the air.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

State government and Hartford city government have figured out the easiest way to solve Connecticut's desperate shortage of inexpensive housing. They just haven't quite realized that they have figured it out.

The solution was presented at City Hall the other week by Mayor Arunan Arulampalam and Gov. Ned Lamont, who announced a $4 million project funded jointly by the state and the city through what is called the Connecticut Home Funds initiative. The project is to turn 18 blighted and abandoned residential properties, condemned by the city long ago, into 20 units of new, owner-occupied housing.

The properties are to be sold to builders for $1 each and the program will help them finance construction. The builders will be required to sell the new houses to people of moderate income at a price that will permit them to be mortgaged for a monthly payment close to the neighborhood's apartment rents. The program aims to increase Hartford's homeownership rate, the lowest in the state at only 23 percent.

The price control involved, while likely to be popular, may be tricky to manage and is mistaken anyway, since it aims to prevent “gentrification" even as Hartford, terribly poor, needs many more residents with higher incomes.

The program's selection of builders also may be troublesome since it is likely to be heavily influenced by political patronage.

But then Connecticut is a one-party state, much in its government is contaminated by patronage, and advocacy of the public interest is so weak here that it's hard to accomplish anything good without patronage.

What is crucial about the Hartford project is its hint that the best way to alleviate the housing shortage isn't to fiddle with zoning regulations and state financial incentives to municipalities but simply to build housing wherever it can be built without aggravating the neighbors too much.

Hartford is hardly alone in being full of dilapidated and underused properties. Connecticut is pockmarked not just with deteriorating tenements but also vacant former factories and commercial buildings. Many city office buildings are half vacant as well now that so many people work from home via the Internet.

Most of these properties would be infinitely more beneficial and attractive to their neighborhoods if replaced by new housing, single- or multi-family, or converted to mixed commercial and residential use -- so much more beneficial and attractive that even the worst snobs might not mind new people moving into town to replace the eyesores. Most of these properties are already served by water, sewer, and utility lines, so housing construction would not chew up the countryside with more suburban sprawl.

But transforming dilapidated and underused properties into the housing that Connecticut needs won't meet the urgency of the moment unless, as Hartford has done, government gains control of the properties and clears the way to their replacement.

No builder or developer wants to spend months or years haggling with a zoning board and pretty-pleasing the neighbors, just as no one who needs housing -- including the children of the very people who object to new housing nearby -- wants to wait months or years for a decent home he can afford.

So addressing the housing shortage with the necessary urgency is a matter of identifying the properties where any housing would be better than leaving the properties as they are. That approach might create more housing in a year than the housing law that Connecticut enacted this year after such controversy.

So an amendment to that law is in order. The law authorizes the state Housing Department to build housing on state government property. The department also should be authorized to condemn and take control of decrepit or abandoned properties anywhere in the state and arrange construction of housing there, and to solicit municipalities to recommend such properties for conversion.

Connecticut has many places where any housing would be better than leaving things as they are. Identify them, level them, build housing on them, and bring housing prices down along with the state's high cost of living.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Hartford in 1877.

No need to walk three times a day

“D-g Days” (carved wood, relief on fabric, paint), by Eva Strum Gross, in a group show called “Novel Formats,’’ opening Jan. 16 at AVA Gallery and Art Center, Lebanon, N.H.

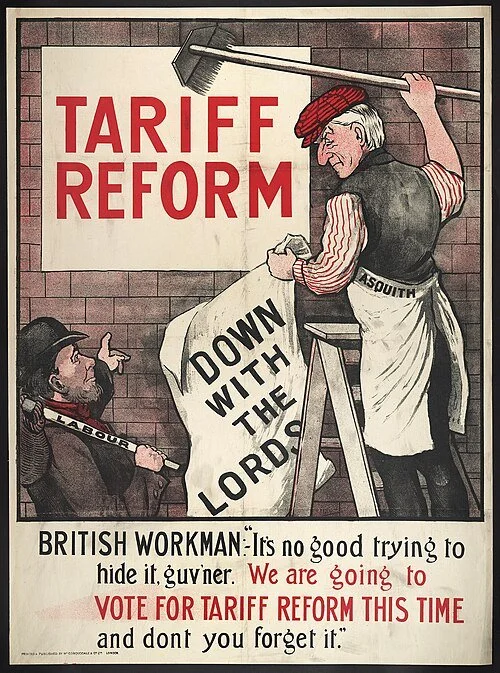

Kent Jones: The taxes that are called tariffs — some history and who gets hit

Cartoon from around 1900.

From The Conversation (except for images above)

Kent Jones is a professor emeritus of economics at Babson College, Wellesley, Mass.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The U.S. Supreme Court is currently reviewing a case to determine whether President Donald Trump’s global tariffs are legal.

Until recently, tariffs rarely made headlines. Yet today, they play a major role in U.S. economic policy, affecting the prices of everything from groceries to autos to holiday gifts, as well as the outlook for unemployment, inflation and even recession.

I’m an economist who studies trade policy, and I’ve found that many people have questions about tariffs. This primer explains what they are, what effects they have, and why governments impose them.

Who pays them?

Tariffs are taxes on imports of goods, usually for purposes of protecting particular domestic industries from import competition. When an American business imports goods, U.S. Customs and Border Protection sends it a tariff bill that the company must pay before the merchandise can enter the country.

Because tariffs raise costs for U.S. importers, those companies usually pass the expense on to their customers by raising prices. Sometimes, importers choose to absorb part of the tariff’s cost so consumers don’t switch to more affordable competing products.

However, firms with low profit margins may risk going out of business if they do that for very long. In general, the longer tariffs are in place, the more likely companies are to pass the costs on to customers.

Importers can also ask foreign suppliers to absorb some of the tariff cost by lowering their export price. But exporters don’t have an incentive to do that if they can sell to other countries at a higher price.

Studies of Trump’s 2025 tariffs suggest that U.S. consumers and importers are already paying the price, with little evidence that foreign suppliers have borne any of the burden. After six months of the tariffs, importers are absorbing as much as 80% of the cost, which suggests that they believe the tariffs will be temporary. If the Supreme Court allows the Trump tariffs to continue, the burden on consumers will likely increase.

While tariffs apply only to imports, they tend to indirectly boost the prices of domestically produced goods, too. That’s because tariffs reduce demand for imports, which in turn increases the demand for substitutes. This allows domestic producers to raise their prices as well.

A brief history of tariffs

The U.S. Constitution assigns all tariff- and tax-making power to Congress. Early in U.S. history, tariffs were used to finance the federal government. Especially after the Civil War, when U.S. manufacturing was growing rapidly, tariffs were used to shield U.S. industries from foreign competition.

The introduction of the individual income tax in 1913 displaced tariffs as the main source of U.S. tax revenue. The last major U.S. tariff law was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which established an average tariff rate of 20% on all imports by 1933.

Those tariffs sparked foreign retaliation and a global trade war during the Great Depression. After World War II, the U.S. led the formation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, or GATT, which promoted tariff reduction policies as the key to economic stability and growth. As a result, global average tariff rates dropped from around 40% in 1947 to 3.5% in 2024. The U.S. average tariff rate fell to 2.5% that year, while about 60% of all U.S. imports entered duty-free.

While Congress is officially responsible for tariffs, it can delegate emergency tariff power to the president for quick action as long as constitutional boundaries are followed. The current Supreme Court case involves Trump’s use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, or IEEPA, to unilaterally change all U.S. general tariff rates and duration, country by country, by executive order. The controversy stems from the claim that Trump has overstepped his constitutional authority granted by that act, which does not mention tariffs or specifically authorize the president to impose them.

The pros and cons of tariffs

In my view, though, the bigger question is whether tariffs are good or bad policy. The disastrous experience of the tariff war during the Great Depression led to a broad global consensus favoring freer trade and lower tariffs. Research in economics and political science tends to back up this view, although tariffs have never disappeared as a policy tool, particularly for developing countries with limited sources of tax revenue and the desire to protect their fledgling industries from imports.

Yet Trump has resurrected tariffs not only as a protectionist device, but also as a source of government revenue for the world’s largest economy. In fact, Trump insists that tariffs can replace individual income taxes, a view contested by most economists.

Most of Trump’s tariffs have a protectionist purpose: to favor domestic industries by raising import prices and shifting demand to domestically produced goods. The aim is to increase domestic output and employment in tariff-protected industries, whose success is presumably more valuable to the economy than the open market allows. The success of this approach depends on labor, capital and long-term investment flowing into protected sectors in ways that improve their efficiency, growth and employment.

Critics argue that tariffs come with trade-offs: Favoring one set of industries necessarily disfavors others, and it raises prices for consumers. Manipulating prices and demand results in market inefficiency, as the U.S. economy produces more goods that are less efficiently made and fewer that are more efficiently made. In addition, U.S. tariffs have already resulted in foreign retaliatory trade actions, damaging U.S. exporters.

Trump’s tariffs also carry an uncertainty cost because he is constantly threatening, changing, canceling and reinstating them. Companies and financiers tend to invest in protected industries only if tariff levels are predictable. But Trump’s negotiating strategy has involved numerous reversals and new threats, making it difficult for investors to calculate the value of those commitments. One study estimates that such uncertainty has actually reduced U.S. investment by 4.4% in 2025.

A major, if underappreciated, cost of Trump’s tariffs is that they have violated U.S. global trade agreements and GATT rules on nondiscrimination and tariff-binding. This has made the U.S. a less reliable trading partner. The U.S. had previously championed this system, which brought stability and cooperation to global trade relations. Now that the U.S. is conducting trade policy through unilateral tariff hikes and antagonistic rhetoric, its trading partners are already beginning to look for new, more stable and growing trade relationships.

So what’s next? Trump has vowed to use other emergency tariff measures if the Supreme Court strikes down his IEEPA tariffs. So as long as Congress is unwilling to step in, it’s likely that an aggressive U.S. tariff regime will continue, regardless of the court’s judgment. That means public awareness of tariffs – and of who pays them and what they change – will remain crucial for understanding the direction of the U.S. economy.

When people are gone

“Station/Frankfurt” (detail) (acrylic on panel), by Peter Waite, in his show “Social Memory, Paintings 1987-2025,’’ at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Conn.

The museum says:

“What if absence were a presence? Peter Waite is known for his large-scale architectural scenes that explore spaces where history, memory, and perception meet. Working in acrylic on rigid panels, Waite’s compositions capture the beauty and poignancy of overlooked corners, faded surfaces, and traces of life that remain when people are gone.’’

Trump hasn’t killed this one

Edited from a New England Council report

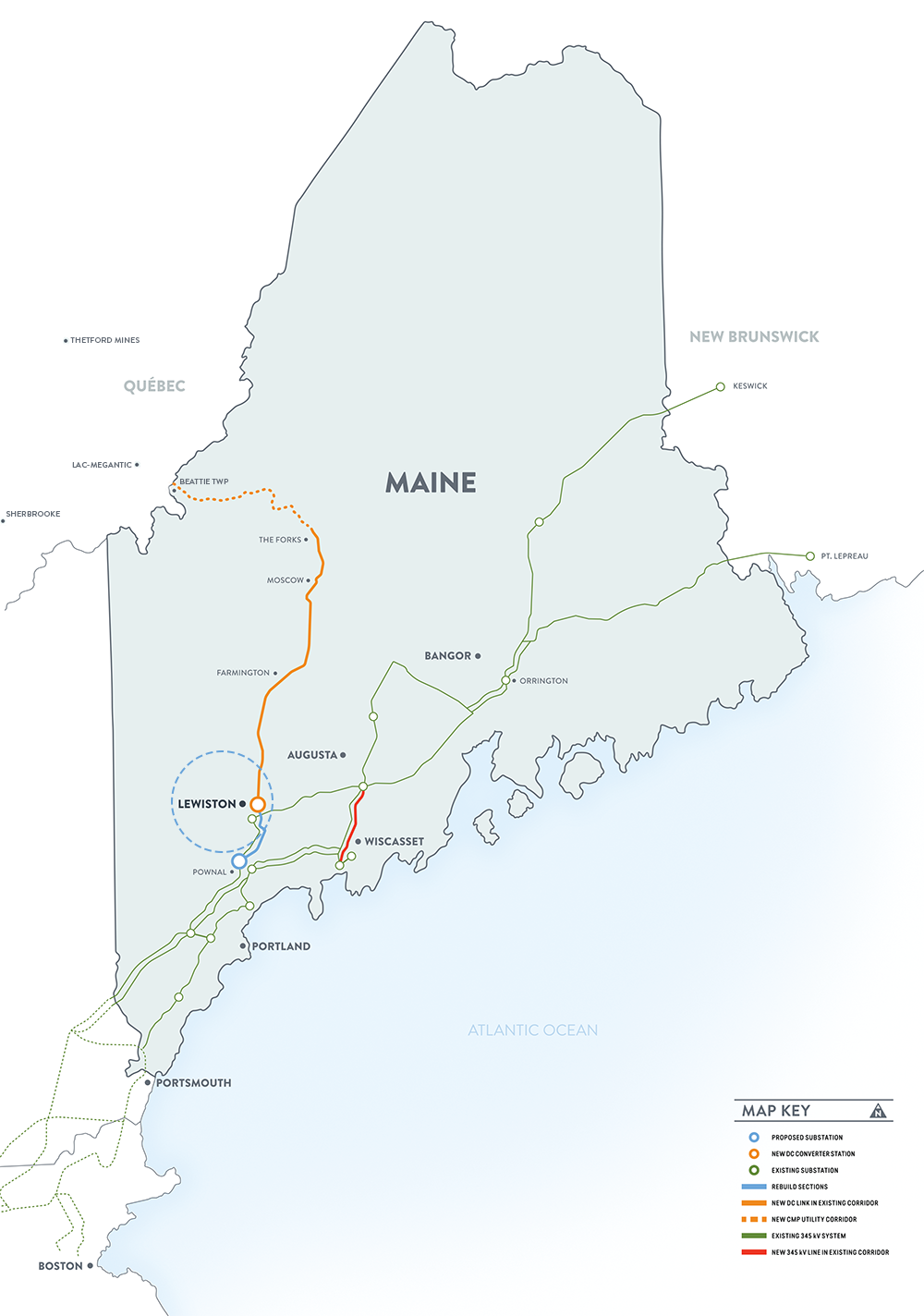

Avangrid announced recently that it has received the last permit needed to begin operation of New England Clean Energy Connect, a 145-mile transmission line that has been in the works for eight years.

The New England Clean Energy Connect has a high-voltage transmission line from Quebec to Lewiston, Mainem, that connects the New England grid to 1,200 megawatts of hydropower from Canada. Avangrid and Central Maine Power are set to have the connection energized very soon.

“This milestone marks the last regulatory step in a rigorous, multi-year process and clears the path for full completion of one of the largest, most transformative energy projects in the region,” Avangrid said in a release. CEO Jose Antonio Miranda emphasized the importance of the project: “We have secured every permit, met every regulatory requirement, and overcome significant challenges because we believe we must address the urgent need for reliable energy at a time of rising demand.”

Reminders of death and life

Macro photo of a snowflake

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

After a day of cold rain last week, amidst the season’s deepening darkness, the sun came out to remind us that in a couple of weeks the days will start getting longer again. Meanwhile some seed catalogs are in the mail.

But snowflakes must fall – trillions of them, and to think that each looks different up close! (I see snowfall as a reminder of the shroud of death on a cloudy day and as a celebration of light and therefore of life on a sunny one.)

The coming of winter-storm season reminds me of the irritating demand that people show up to work at the newspapers where I labored regardless of the weather. In my case most memorable was trudging and climbing home from The Providence Journal in the Blizzard of ’78 and walking home as branches were still falling during the tail end of Hurricane Bob in 1991.

But as the great English playwright, songwriter and director Noel Coward asked: “Why Must the Show Go On?’’ Here’s the song.

xxx

I have fond memories from childhood of visiting what’s now called the Edaville Historic Train & Festival of {holiday} Lights, whose origins go back to 1947. It’s magical place (at least for children) in South Carver, Mass. in the heart of Cranberry Country. Check it out.

At this time of year, any place with bright lights, colored or just white, is much appreciated.

Boston readies for FIFA

FIFA games will be played at Gillette Stadium, in Foxboro, Mass. It will be called “Boston Stadium’’ for these games. Gillette is the home of the New England Revolution soccer team.

By Brendan Cassidy in The Boston Guardian

(New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian’s board.)

As Boston prepares to host seven 2026 FIFA World Cup matches next summer, Meet Boston has formed a new group to help ensure that the legacy of these games is carried on.

The group, called the Greater Boston Sports Commission, will help pursue opportunities for the city to host more games and events in the future.

Meet Boston President Martha Sheridan announced the formation of the group at Meet Boston’s annual meeting on Tuesday, Dec. 2.

Meet Boston is a marketing and visitor services organization focused on driving tourism-related business in the city.

Successes of the organization, ongoing happenings and plans for the future were discussed at Tuesday’s meeting.

The first order of the Greater Boston Sports Commission is to support the delivery of the World Cup games to Boston in 2026.

In the future, the group hopes to help bring events like the FIFA Women's World Cup and the NBA All-Star Game to the city, said Sheridan.

The seven World Cup matches taking place in Boston next year have an estimated economic impact of $1 billion, according to Meet Boston.

“The eyes of the world will be on the best city on the planet next summer,” said Mayor Michelle Wu, who spoke at the meeting.

Sheridan said that sports tourism has been a long-term priority of Meet Boston.

Meet Boston will also look to increase its supplier diversity imprint in 2026 with the help of Conan Harris & Associates.

Meet Boston and Conan Harris will partner on a program called P.A.T.H., which stands for promoting advancement and tourism and hospitality.

P.A.T.H hosts events like career fairs aiming to connect culturally diverse individuals with employers in the hospitality industry.

“Meet Boston saw that there was a gap,” said Harris. “They wanted to open up this industry to the Greater Boston community, to diverse Boston.”

The organization will be rolling out a new platform in 2026 meant to expand partnerships with minority, women and veteran owned businesses.

“Diversity, equity and inclusion remains at the heart of everything we do,” said Meet Boston Community Engagement Liaison Michael Munn in a video presented to attendees.

Promoting green travel practices citywide and limiting carbon footprint will continue to be a focus of Meet Boston in 2026.

Currently, Meet Boston’s “Frostival” programming is taking place, offering a number of winter activities through February.

“This programming will completely transform and reimagine winter in Boston,” read a Meet Boston press release.

In December, drone shows will take place over the Boston Common each Saturday night.

Copley Square will be transformed to host an immersive experience during the Winter Olympics in February, which take place in Milan. There are also plans for a Ferris wheel on the Rose Kennedy Greenway in February.

Water’s marks

“Holding Not Having (after Robin Messing)” (chromogenic dye coupler print), by Mary Mattingly, in her show “Water Writes the Garden,’’ at The Current gallery, Stowe, Vt., opening Jan. 15.

The gallery says the solo exhibition “unites photographs, sculptures, and poetry around water’s role as timekeeper and storyteller. It explores how water makes marks and sculpts environments through cyclical formation and erosion. What does water remember? And what does it write into the landscape? Here, gardens are both cultivated and fugitive.’’

William Morgan: Coin honoring traitor and wanna-be tyrant Trump reflects America’s moral rot

PROVIDENCE

Seemingly prepared to bypass this nation’s historical aversion to monarchy, our extremely narcissistic Apricot Toddler sees himself as a Roman emperor, perhaps Nero or Caligula. In college, I recall reading Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. In the opening chapter, published in 1776, the great English historian notes that one of the surest indicators of an empire’s impotency is the diminished quality of the design of its coins. The announcement that the U.S. Treasury will mint a one-dollar piece with Trump’s face on both sides is a harbinger of the inevitable implosion of the reign of Trumpus Anti-Americanus.

The double-Trump dollar (surprisingly, not in gold) typically violates laws and traditional shibboleths, such as depicting a living person on currency (banned by Congress in 1866), to say nothing of a lack of modesty and dignity. The obverse leonine profile of the wannabe dictator is a handsome enough rendering, perhaps inspired by another living person depicted on contemporary currency, Britain’s King Charles.

The reverse, however, with its depiction of the assassination attempt during the presidential campaign, is on a par with the weakest Soviet realism. Far too detailed for a coin, it is crowded by the echoing “Fight Fight Fight’’. “Liberty,” mandated for all currency by Congress in 1782, is pretty simple to grasp, but what to make of Trump’s trite football cheer?

British 5-pence coin at left; 5-pound coin at right

Theodore Roosevelt, a neither culturally hollow or aesthetically challenged president, was concerned about the visual message of our currency (“I think the state of our coinage is artistically of atrocious hideousness”), recognizing that good design spoke of the symbolism and perhaps the probity of the government that issued it. T.R. hired America’s greatest sculptor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, to personify Liberty as a goddess in the best classical manner. The Saint-Gaudens “double eagle” was in circulation from 1907 to 1933.

The beauty of the Saint-Gaudens $20 gold piece notwithstanding, the Trumpian deification dollar is right on track, seemingly nearing the end point of a string of declining visual signposts from the U.S. Treasury.

The state commemoratives, starting in the late 1990s, serve as examples of a worsening design sense. One of the early strikes, Connecticut, was almost excellent. The Charter Oak is a potent symbol, and its rendering demonstrates an understanding of the nature of a coin, that is not being a “picture’’. Alas, the dates and the legends add unnecessary clutter.

The nod to Ohio, three years after Connecticut, hasn’t a clue of what a coin ought to be. The design is a crowded mess. There’s the map of the Buckeye State, a faceless and footless Neil Armstrong on his moon walk, and the Wright Brothers’ plane (which flew not in Ohio, but in North Carolina).

When there were no more states to pimp, the Mint began issuing quarters featuring places (the White Mountains, say, or the Florida Everglades – landscapes are not ideal for the miniature circular canvases) or people (Helen Keller, Duke Ellington) or events (the Homestead Act).

Almost all of the quarters featuring people border on the grotesque, but that honoring the late Hawaiian Congresswoman Patsy Mink serves as exemplary of the low quality of noted-people portraits. Here we are offered a dog’s breakfast of competing detail: Patsy’s name, the U.S. Capitol, Title IX legislation, a lei, “Equal Opportunity in Education’’, and what looks like an erect right nipple. No one, even a politician, deserve such an embarrassingly artless tribute.

The Trump dollar is, thus, not all that unusual: the nadir of a bad stretch in the numismatic wilderness. It is not coincidental that it arrives following the imminent cessation of the minting of the one-cent coin. While there may be economic reasons for ending the life of the penny, a chief reason is arguably that it features Abraham Lincoln. Honest Abe’s presence on the penny is a constant affront to our most dishonest, traitorous, and authoritarian president.

Our coins are cultural barometers, and the Trump double dollar is the perfect reflection of the moral rot that threatens our republic.

Architectural historian and photographer William Morgan writes about design in all forms, including cities, architecture, landscapes, and license plates. He is the author of Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, among other titles.

We’re mostly water anyway

From Sheryl Bentley’s show “Watermarked: Liquid Snapshots of the Strange and Unusual,’’ at the Greater Concord (N.H.) Chamber of Commerce’s Capitol Region Visitor Center through Jan. 13

Llewellyn King: AI and our robotic future

The robot Maria from the 1927 German expressionist film Metropolis

Editor’s Note: Visit the fabulous MIT Museum, in Cambridge, Mass., to check robotic-related stuff.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The next big thing is robots. They are, you might say, on the move.

Within five years, robots will be doing a lot of things that people now do. Simple repetitive work, for example, is doomed.

Already, robots weld, bolt and paint cars and trucks. The factory of the future will have very few human workers. Amazon distribution centers are almost entirely robot domains. Robots search the shelves, grab items, pack and send them to you — often seconds after you have placed your order.

Of course, these orders will be delivered in vans, which must be loaded carefully, even scientifically. The first out must be the last in; small items must nestle with large ones. Space is at a premium, so robotic brains will do the sorting and packing swiftly, efficiently and inexpensively.

Very soon, the van will be self-driving: a robot capable of navigating the traffic and finding your home. At first, it may not get further in the delivery chain than calling you to say that your package has arrived. Eventually, humanoid robots may ride in the vans and, yes, hand your package to you. No tipping, please.

When we think about robots, we tend to think of the robots that look like us. The internet is full of clips of them climbing stairs, playing sports and doing backflips.

There are reasons for humanoid robots: They are less intimidating with their humanlike heads, two arms with hands and two legs with feet than a machine with many arms or legs. Also, most of the tasks the robot is taking over are done by humans. The tasks are fitted to people, such as pumping gas, preparing vegetables or painting a wall.

The first big incursion may be robotaxis. Waymo taxis are already operating in five cities, and the company has plans to roll them out in 19 cities. Several cities are concerned about safety, including Houston and Seattle, and want to ban them. But there are state-city jurisdictional issues about implementing bans.

A likely scenario, as with other bans, is that the development will go elsewhere. Travelers tend to eschew places where Uber and Lyft aren’t allowed to operate in favor of those where they are.

You are already dealing with robots when you talk to a digital assistant at an airline, a bank, a credit card or insurance company, or any business where you call a helpline. That soothing, friendly voice that comes on immediately and asks practical questions may be a robot: the unseen voice of artificial intelligence.

In the years I have been writing about AI and its impact on society, I have consistently heard the AI revolution and its impact on jobs compared with the Industrial Revolution and automation. The one led to the other and in the end, many new jobs and whole new ecosystems flourished.

It isn’t clear that this will happen again and if so on what timetable. A lot of jobs are already in danger, from file clerks to delivery and taxi drivers, from warehouse workers to longshoremen.

AI is also changing the tech world. A whole new tier of companies is emerging to carry forward the AI-robot revolution. These are companies that make robots; companies that write software, which will give robots brainpower; and companies that will have a workforce that maintains robots.

These emerging companies will need a workforce with a different set of skills — skills that will keep the new AI economy humming.

What is missing is any sense that the political class has grasped the tsunami of change that is about to break over the nation. In just a few years, you may be riding in a robotaxi, watching a humanoid robot doing yard work or lying on a couch and chatting with your robot psychiatrist.

Our species is adaptable, and we have adapted everything from the wheel to the steam engine to electricity to the internet. And we have prospered.

Time to think about how to prosper with AI and its robots.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is host and executive producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS, as well as an international energy-sector consultant. He’s also a former publisher and editor.

Chlorine carnival

“Swim Lesson” (encaustic collage), by Nancy Whitcomb, in The Providence Art Club’s annual Little Pictures Show. She is a member of New England Wax.

‘Reimagined histories’

In Larissa Bates’s sh0w “Motherland/La Madre Patria,’’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Conn., Jan. 15-May 25.

The museum says Ms. Bates, whose are paintings are in gouache, egg tempera, and acrylic ink, explores her bicultural upbringing— ‘‘bridging the cloud forests of Costa Rica with rural Vermont, where her father was part of the experimental architecture community in Prickly Mountain. Her robust visual language stitches together fragments of objects, rooms and landscapes from her youth into reimagined histories, a framework through which she reconciles personal memory and feelings of cultural loss.’’

Chris Powell: Merchants are more honest than Sen. Blumental about debt

In the early 20th Century, the National Consumers League promoted the “Shop Early Campaign". This systematic multi-year publicity campaign used cartoons, letters, editorials, articles and advertisements, sending materials to hundreds of newspapers and retailers across America.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

What would the holidays be in Connecticut without U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal warning his constituents about the perils of the season -- dangerous toys, fraudulent business practices, Republicans, and the like? (Poking the Russian bear on its own doorstep has yet to make the senator's list.)

Last week the senator affected alarm about merchants who advertise products available for purchase with deferred payments -- “buy now, pay later" promotions. People who purchase something by agreeing to pay in the future may find that when the bill comes due that their financial situation has deteriorated. Worse, the senator notes, being late with a deferred payment may trigger penalty interest charges.

Of course, anyone who has graduated from high school might suspect these risks. But then maybe the senator understands that many Connecticut high-school graduates can't read, write, and do math at a high school or even an elementary-school level.

In any case the senator overlooks an argument in favor of “buy now, pay later" purchases, an argument that members of Congress especially should understand: inflation and the decline of the value of the U.S. dollar and wages paid in dollars. Amid inflation certain goods -- if not worn out, damaged, or perishable -- may actually increase in value and, when payment has to be made, may be worth more than their original price.

Indeed, Blumenthal misses the great irony in his warning people against deferred-payment schemes: his having been for the last 15 years an enthusiastic supporter of the federal government's own “buy now, pay later" policy.

For the federal government increasingly finances itself with borrowing, and its total debt now exceeds $38 trillion, an unfathomable number.

Government debt is not necessarily bad; it can be productive. But this is a matter of degree, and in recent years the federal debt has gone wild, as suggested by the country's recent severe inflation and the heavy burden of federal government interest payments, estimated at about a trillion dollars annually and rising.

Most of this debt is not for long-lasting capital projects that will benefit the country for decades but for ordinary operating expenses and income supports, with the interest requiring payment far into the future by people who never benefited from the debt.

This is borrowing for current expenses, which used to be considered immoral. But in national politics today, especially among Democrats like Blumenthal, money is believed to be infinite. (Most Republicans know better without acting much better.)

Today in Congress if any Democrat sees a need, actual or merely political, he'll put it into an appropriations bill, and, if he's friendly enough with the ranking Democrat on the House Appropriations Committee, Connecticut Rep. Rosa DeLauro, she'll put it into the next federal budget with no concern about the federal debt, inflation, or interest burdens.

Members of Congress love this system because it lets them distribute infinite goodies, essential or not, and pay for them indirectly, not with taxes but with inflation, a disguised tax few voters understand or can fix responsibility for.

That's why the merchants promoting deferred payments are actually more honest than the senator who is warning his constituents against them.

Stick to a merchant's deferred-payment plan and you'll pay only as much as you signed up to pay. But with the federal government, whose costs are increasingly financed by borrowing, debt monetization, and inflation, you pay now, later, and -- since the debt is never actually repaid at all, but just keeps rising -- you pay for the rest of your life as well for what you get or once got from the federal government, and for what you didn't get but others get or used to get.

So what's really more dangerous -- the toys Blumenthal is scorning, whose small parts a 2-year-old might pull off and swallow or stick in his nose or ear, or a government that, when the kid turns 18, will welcome him into adulthood largely ignorant and unskilled but, as a taxpayer, already heavily mortgaged?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Incredible!They did it without credit cards!

Downtown Boston during the 1912 Christmas shopping season.

‘How not to be lonely’

Downtown Worcester from Norfolk Street. The city is in a very hilly area.

Photo by Terageorge

“When I was a boy in Worcester, Massachusetts, my family lived on the top of a hill, at the thin edge of the city, with woods beyond. Much of the time I was alone, but I learned how not to be lonely, exploring the surrounding fields and the old Indian trails.’’

— Stanley Kunitz (1905-2006), poet, including as the U.S. poet laureate