And adjusted for inflation since then?

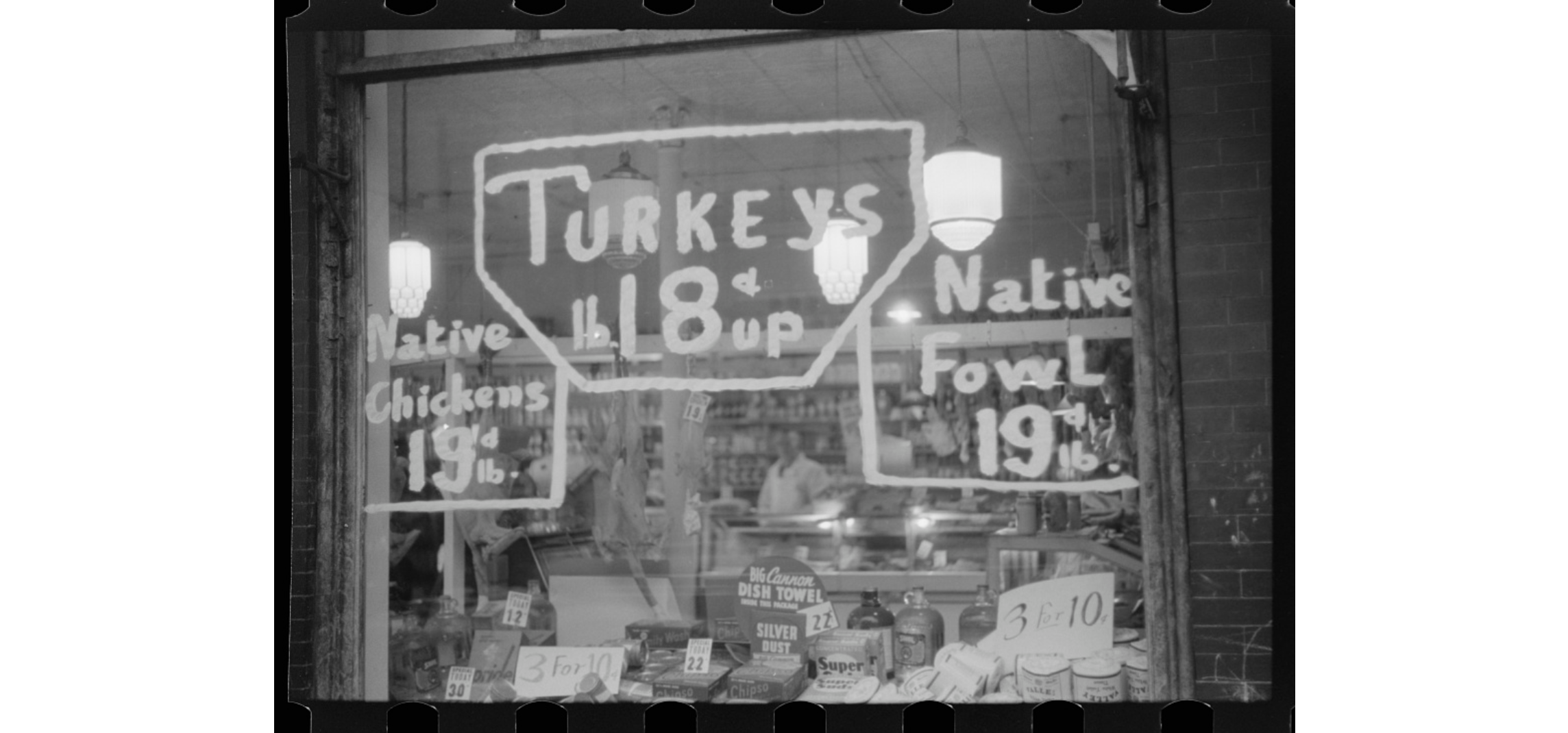

A butcher shop window in Norwich, Conn., during Thanksgiving week in 1940, by famed photographer Jack Delano (1914-1997), perhaps most famous for his Great Depression era photos.

No screwballs like him

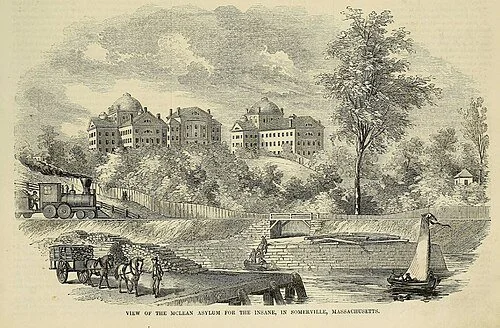

Print of the McLean Asylum (founded in 1811) in 1853, in Somerville, Mass. The hospital was moved to Belmont in 1895.

“In between the limits of day,

hours and hours go by under the crew haircuts

and slightly too little nonsensical bachelor twinkle

of the Roman Catholic attendants.

(There are no Mayflower

screwballs in the Catholic Church.)''—From “Waking in the Blue,’’ by American poet Robert Lowell (1917-1977). The poem is based on his stay in McLean Hospital, a psychiatric institution in Belmont, Mass., that became famous, for among other things, a place for very discreetly treating celebrities such as Lowell. A descendent of Mayflower passenger James Chilton, he suffered from bi-polar disorder.

Read Alex Beam’s book Gracefully Insane: Life and Death Inside America's Premier Mental Hospital.

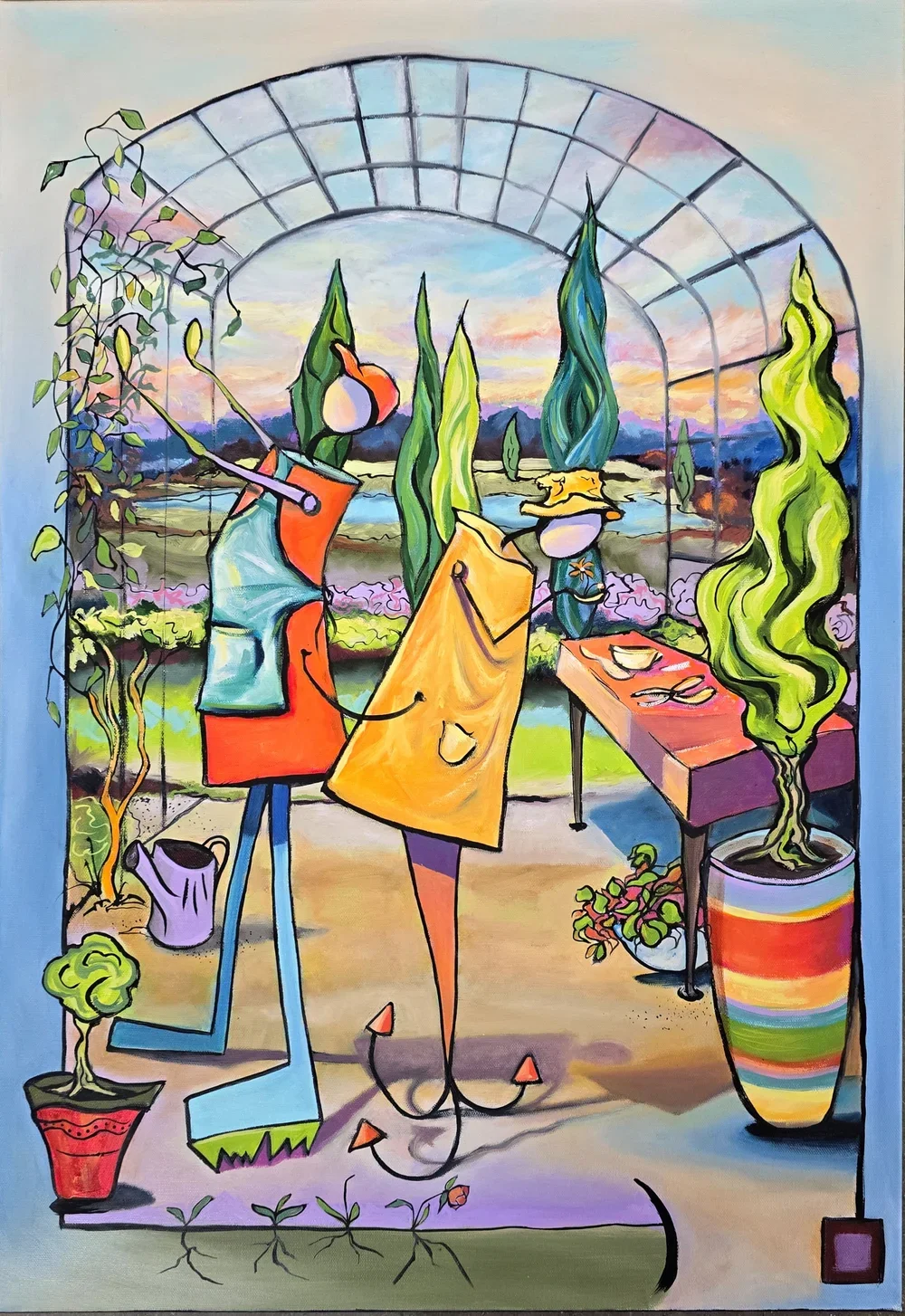

‘Driven by raw emotion’

Painting by New Hampshire artist Brian Wagoner, whose artist name is Bunkt, in his show “Give and Take: Works by Bunkt,’’ at 3S Artspace, Portsmouth, N.H., through Nov. 30.

The gallery says:

“Bunkt’s art is driven by raw emotion–– an interplay of anxiety, excitement, and anger emerging from within chaos. His studio floor is strewn with supplies and unconventional materials, reflecting a process that is ever-changing and experimental. Each painting evolves through countless transformations—glued, stapled, burnt, cut, and rearranged—revealing a story of hardship and resilience.’’

He’s a self-taught and began his public artistic career at age 45.

Melancholy metro

Newbury Street, Boston, in 1880, before all the expensive shops moved in.

Grappling with history

Work by painter and Holocaust survivor Samuel Bak (born 1933), in his show “Question of Life,’’ at Pucker Gallery, Boston, through Dec. 7.

Mannie Lewis: Women did most of the work at the myth-thick “First Thanksgiving’’

“The First Thanksgiving, 1621” (oil on canvas), by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1899). The painting shows common misconceptions about the event, in what is now Plymouth, Mass., that persist to today. Pilgrims did not wear such outfits, nor did they eat at a dinner table. The Wampanoags are dressed in the style of Native Americas living on the Great Plains.

From The Boston Guardian (except for picture above)

(New England Diary’s editor, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

As you sit down for Thanksgiving dinner this year, consider including these people in your list of reasons to be grateful, Susanna White, Elizabeth Hopkins, Eleanor Billington and Mary Brewster.

Like many a good gathering, they did most of the work but reaped little of the credit. They were the only four grown women present at the first historic feast in 1621, according to records. These women cooked a three-day feast for 53 pilgrims and about 90 Wampanoag men.

The four women who made the meal that became known as the first Thanksgiving did so because they were the four women who survived to see it. Five young girls lived as well.

Primary sources on the first Thanksgiving are scant.

William Bradford, the tiny colony’s leader, wrote one of just two primary accounts known to date.

“They begane now to gather in the small harvest they had, and to fitte up their houses and dwellings against winter, being all well recovered in health and strenght, and had all things in good plenty; for as some were thus imployed in affairs abroad, others were excersised in fishing, aboute codd, and bass, and other fish, of which they tooke good store, of which every family had their portion,” he said.

Edward Winslow kept the other record. As it turns out, he married Susanna White, the first of our four Thanksgiving chefs, after her husband William White died.

Largely what is known of the women at the first Thanksgiving is based on their associations to their husbands.

Many historians note that Susanna White was friends with Elizabeth Hopkins, wife of Stephen Hopkins, but little else is known of Hopkins.

Eleanor Billington and her family had a reputation for being troublesome. Her son Francis drew scorn for firing a musket inside the Mayflower. Her husband John was executed for murder in 1630.

Mary Brewster and her husband, William, were known for their religiosity, and William Brewster’s role as a Pilgrim leader continues to be celebrated by his descendants through the Elder William Brewster Society.

The accomplishments of those such as William Brewster, William Bradford and their contemporary men are well documented. Lesser known are the women who made the first feast, whose biographies are short and whose tasks were likely limited.

Those not included at all. Historical mentions of Wampanoag women at the first feast are even scarcer.

Berlin’s paper past

From the Brown Company Photographic Collection at the Museum of the White Mountains, at Plymouth (N.H.) State University, about the once big paper industry centered in Berlin, N.H., in a region with forests providing the mills with raw material.

The museum explains:

The Brown Company Photographic Collection documents the history of the company’s paper mill from the late 19th Century through the mid-1960s.

Much of the collection chronicles the social, cultural, and recreational lives of the workers, their families, and the place of these people in the life of Berlin. The images, which are accessible from the Web site, let viewers add written content about the photographs, or to share information about the paper mill by telephone.

Chris Powell: The case for vegetarianism is getting stronger

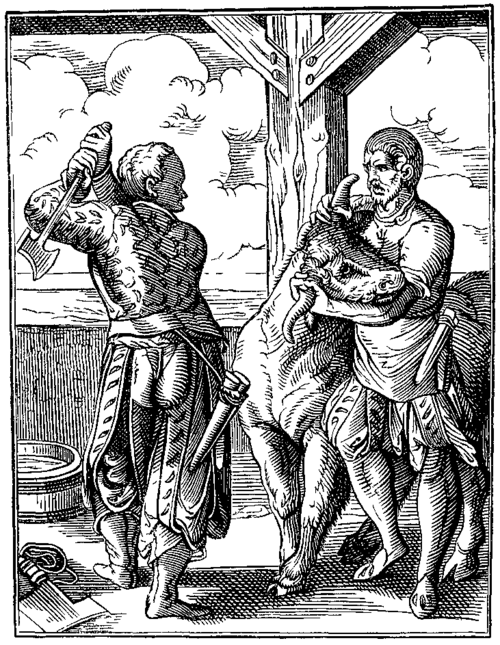

“The Butcher and his Servant’’ (1568), drawn and engraved by Jost Amman

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Wesleyan University, in Middletown, Conn., often rivals Yale University in New Haven for nutty political correctness, and that's how many people perceived its most recent news. A group of Wesleyan students, faculty members, and alumni has asked the university to erect a plaque outside the university's dining hall to memorialize all the animals killed for the food eaten inside.

Such a plaque would be a rebuke not just to meat eaters on campus but to the university itself, so it's hard to see how Wesleyan could erect it without also taking meat off the dining hall menu and formally converting the campus to vegetarianism. Once the plaque was erected, anything less would be hypocrisy.

Such a plaque also might make the university's priorities seem strange, what with poverty, homelessness, child neglect, and other human ills worsening throughout Connecticut, often within sight of the university.

Even so, the plaque concludes: “There will come a time when we will look back on this treatment of our fellow animals as indefensible. We will recognize that all animals feel, think, love, and strive to live -- even those who do not look or behave exactly as humans do -- and that their lives are as precious to them as ours are to us."

Pigs being transported to be slaughtered and eaten, much of the meat as bacon.

This is not so nutty, insofar as society has already conceded some of it in principle with laws against gratuitous cruelty to animals. But vegetarianism is up against all history, starting with animals themselves, many of which have no scruples against eating each other.

In Genesis the Bible conveys divine approval for eating meat: “And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the Earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the Earth."

Indeed, without the meat industry many animal species and breeds, being raised primarily for food, might virtually disappear. Who would go through the trouble and expense of raising beef cattle just for the sake of biodiversity?

But guilt about eating meat is not peculiar to Wesleyan. There is much ethics-based vegetarianism in Hinduism, and some American Indian tribes offered prayers of thanks to honor the animals they hunted for food, though whether this was sincere respect or just rationalization for participating in the kill is arguable. Few people ordering hamburgers have to witness the prerequisite slaughtering and butchering of the animals that their meat comes from. Witnessing such spectacles in the stockyards and meat-packing factories can depress appetites.

Of course, vegetarianism does not automatically confer goodness. Taking a break from plotting mass murder in November 1941, Hitler assured his dinner companions, “The future belongs to us vegetarians."

It's still better that he lost the war.

But the case for vegetarianism, or at least for greater respect for animals, is getting stronger for new reasons.

Companion animals, particularly dogs and cats, long have been famous for their sometimes uncanny ability to communicate with and protect people. But in recent years home videos posted on the Internet have proven what had been mainly anecdotal -- the astounding intelligence and ability to communicate with humans possessed not just by dogs and cats but even by wild animals, farm animals, and birds as well.

Amelia Thomas, a journalist, animal scientist, and farmer in Canada, has detailed this in a fascinating new book, What Sheep Think About the Weather: How to Listen to What Animals Are Trying to Say.

“There's no us and them," Thomas says. “Rather, infinite varieties of us."

Chimpanzees are humans’ closest relatives.

Having worked a little with chimpanzees, some of whom have learned American sign language, Thomas quotes the primatologist Mary Lee Jensvold: “The more you appreciate what thinking beings they are, the more you also understand the depth of their suffering."

There are no chimps on the menu at Wesleyan, but if the vegetarian plaque is erected there, over time it may get harder to argue with.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government, politics and other topics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Llewellyn King: The biggest sources of stress for air-traffic controllers

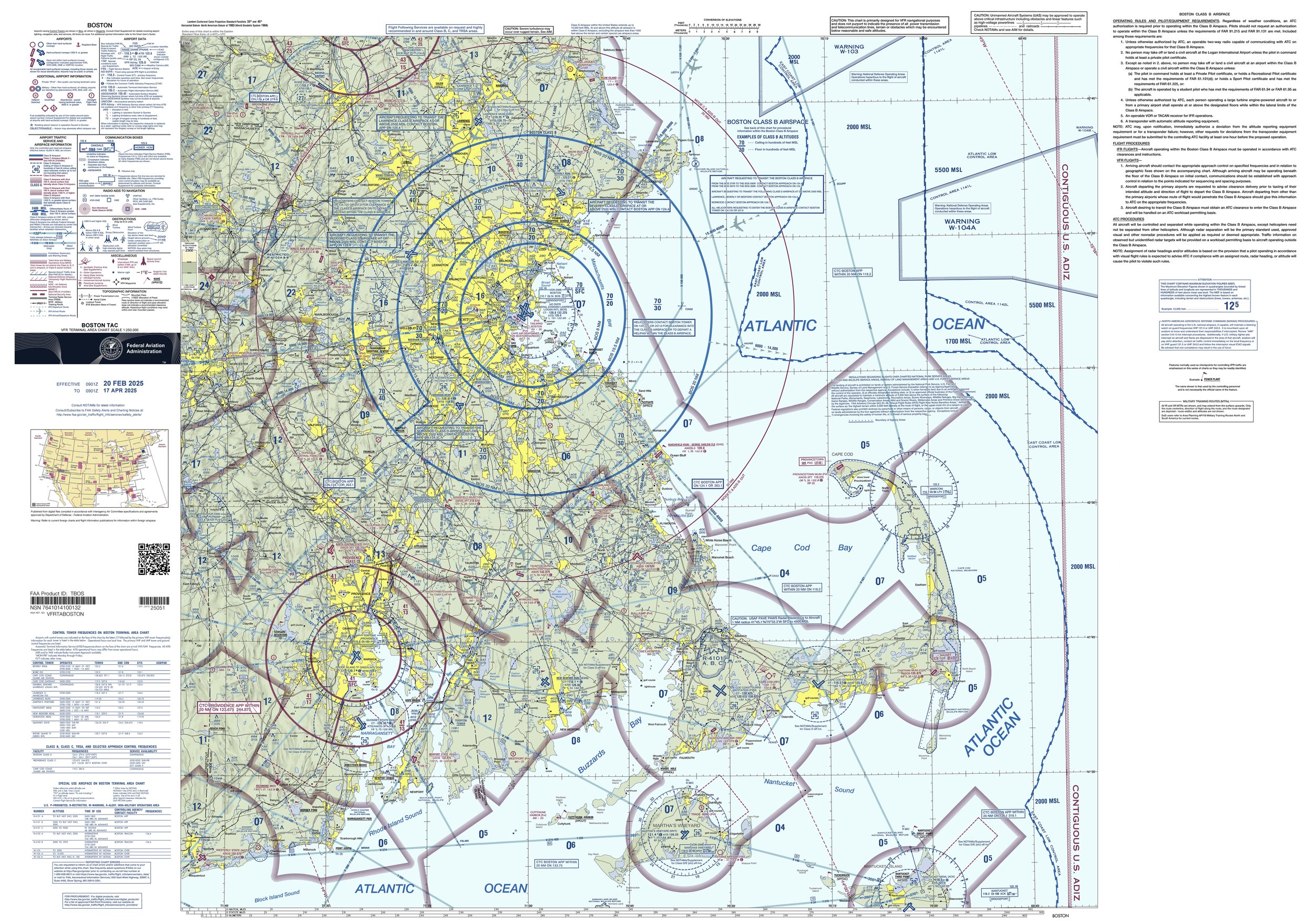

Air-traffic-control zones in the southeast corner of New England.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

If you don't know about the stress that air-traffic controllers are reportedly under, then maybe you are an air-traffic controller.

The fact is that air-traffic controllers love what they do — love it and wouldn't do anything else.

The stress comes with long hours, Federal Aviation Administration bureaucracy and a general lack of recognition, not with moving airplanes safely about the sky.

Of course, I haven't interviewed every controller, but I have talked to a lot of them over the years and have been in many control towers.

Controllers love the essentiality of it. They love aviation in all its forms.

They love the man-and-machine interface, which is at the heart of modern aviation. They love the sense of being part of a great system — the power, the language, the satisfaction.

They love the trust that every pilot puts in them. It is rewarding to be trusted in anything, but more so when the price of failure is known.

Nearly everything that is true of pilots is true of controllers. At its heart, the job is about flight, arguably the greatest achievement of mankind, the fulfillment of millennia of yearning.

There is a saying often attributed to Winston Churchill that was actually said by a pilot and insurance executive in the 1930s: “Aviation in itself is not inherently dangerous. But to an even greater degree than the sea, it is terribly unforgiving of any carelessness, incapacity or neglect."

That is true both of pilots and those at the consoles on the ground, who co-fly with them.

After President Ronald Reagan fired more than 11,000 striking controllers in 1981, some of the saddest people I knew were air-traffic controllers.

They were denied the right to do the work that they loved and suffered immeasurably for that. A few were able to get work overseas, but mostly it was a light that went out and stayed out.

I ran into one former controller, working as a baggage handler. He said he just wanted to be near the action even if he couldn't go into the tower anymore and do his dream job.

My only major criticism of Reagan in this case has always been that he didn't rehire the strikers after he had won, proving that they were wrong in striking illegally and that they weren't above the law.

Reagan was often a compassionate man, but he showed the controllers no compassion. I think that if he had understood the psychological pain he had inflicted, he would have relented.

Controllers have explained to me that if a controller finds the job stressful, then he or she shouldn't be a controller.

About one-third of the candidates for controllers' school, most of whom are trained at the FAA Academy in Oklahoma City, flunk out.

It takes longer to train a controller than a pilot — maybe not to work in the cockpit of a passenger jet, but certainly to fly an aircraft, including jets. It takes at least four years of schooling, simulator and then supervised controlling to qualify to be an FAA controller. Some controllers come from the military.

There is just one movie about air-traffic control, released in 1999, Pushing Tin. It flopped at the box office but has a cult following among pilots and controllers. It is funny and accurate. Pushing tin is controllers' jargon for what they do: push airplanes around the sky.

The fabled stress, in my mind, is the adrenaline factor. It is present in air-traffic control, and it is present in the cockpit of everything that leaves the ground, from single-engine Cessnas to Boeing 777s — and in ATC facilities.

It interests me that pilots rarely mention stress. It is, however, always mentioned by people writing about or talking about air-traffic control. I would venture that the most stress that controllers deal with is the stress imposed on them by the FAA.

I will aver that in the recent and record-long government shutdown, the largest source of stress for controllers was how they were going to put food on the table and pay their bills, not the stress that they feel at the console, pushing tin and keeping flying safe. Now they are stressed about back pay.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS and an international energy-sector consultant.

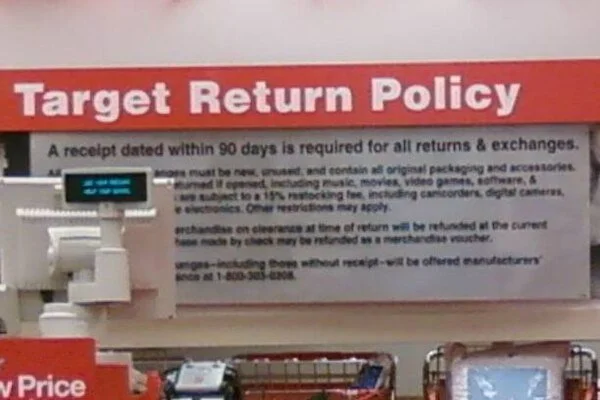

Lauren Beitelspacher: Beware stores’ new return policies

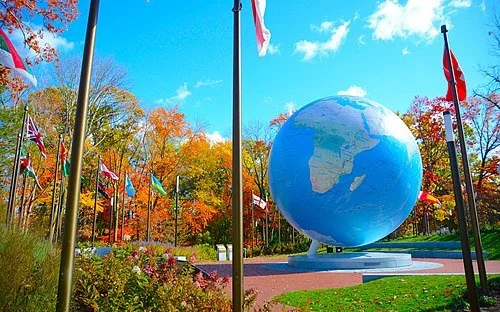

The Babson Globe, at the college’s campus, in Wellesley, Mass.

From The Conversation, except for images above.

Lauren Beitelspacher is a professor of marketing at Babson College, Wellesley Mass.

She does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

’Tis the season for giving – and that means ’tis the season for shopping. Maybe you’ll splurge on a Black Friday or Cyber Monday deal, thinking, “I’ll just return it if they don’t like it.” But before you click “buy,” it’s worth knowing that many retailers have quietly tightened their return policies in recent years.

As a marketing professor, I study how retailers manage the flood of returns that follow big shopping events like these, and what it reveals about the hidden costs of convenience. Returns might seem like a routine part of doing business, but they’re anything but trivial. According to the National Retail Federation, returns cost U.S. retailers almost US$890 billion each year.

Part of that staggering figure comes from returns fraud, which includes everything from consumers buying and wearing items once before returning them – a practice known as “wardrobing” – to more deceptive acts such as falsely claiming an item never arrived.

Returns also drain resources because they require reverse logistics: shipping, inspecting, restocking and often repackaging items. Many returned products can’t be resold at full price or must be liquidated, leading to lost revenue. Processing returns also adds labor and operational expenses that erode profit margins.

How e-commerce transformed returns

While retailers have offered return options for decades, their use has expanded dramatically in recent years, reflecting how much shopping habits have changed. Before the rise of e-commerce, shopping was a sensory experience: Consumers would touch fabrics, try on clothing and see colors in natural light before buying. If something didn’t work out, customers brought it back to the store, where an associate could quickly inspect and restock it.

Online shopping changed all that. While e-commerce offers convenience and variety, it removes key sensory cues. You can’t feel the material, test the fit or see the true color. The result is uncertainty, and with uncertainty comes higher rates of returns. One analysis by Capital One suggests that the rate for returns is almost three times higher for online purchases than for in-store purchases.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the move toward online shopping went into overdrive. Even hesitant online shoppers had to adapt. To encourage purchases, many retailers introduced or expanded generous return policies. The strategy worked to boost sales, but it also created a culture of returning.

In 2020, returns accounted for 10.6% of total U.S. retail sales, nearly double the prior year, according to the National Retail Federation data. By 2021, that had climbed to 16.6%. Unable to try things on in stores, consumers began ordering multiple sizes or styles, keeping one and sending the rest back. The behavior was rational from a shopper’s perspective but devastatingly expensive for retailers.

The high cost of convenience

Most supply chains are designed to move in one direction: from production to consumption. Returns reverse that flow. When merchandise moves backward, it adds layers of cost and complexity.

In-store returns used to be simple: A customer would take an item back to the store, the retailer would inspect the product, and, if it was in good condition, it would go right back on the shelf. Online returns, however, are far more cumbersome. Products can spend weeks in transit and often can’t be resold – by the time they arrive, they may be out of season, obsolete or no longer in their original packaging.

Logistics costs compound the problem. During the pandemic, consumers grew accustomed to free shipping. That means retailers now often pay twice: once to deliver the item and again to retrieve it.

Now, in a post-pandemic world, retailers are trying to strike a balance – maintaining customer goodwill without sacrificing profitability. One solution is to raise prices, but especially today, with inflation in the headlines, shoppers are sensitive to price hikes. The other, more common approach is to tighten return policies.

In practice, that’s taken several forms. Some retailers have begun charging small flat fees for returns, even when a customer mails an item back at their own expense. For example, the direct-to-consumer retailer Curvy Sense offers customers unlimited returns and exchanges of an item for an initial $2.98 price. Others have shortened their return windows. Over the summer, for example, beauty retailers Sephora and Ulta reduced their return window from 60 days to 30.

Many brands now attach large, conspicuous “do not remove” tags to prevent consumers from wearing items and then sending them back. And increasingly, retailers are offering store credit rather than cash or credit card refunds, ensuring that returned sales at least stay within their company.

Few retailers advertise these changes prominently. Instead, they appear quietly in the fine print of return policies – policies that are now longer, more specific and far less forgiving than they once were.

As we head into the busiest shopping season of the year, it’s worth pausing before you click “purchase.” Ask yourself: Is this something I truly want – or am I planning to return it later?

Whenever possible, shop in person and return in person. And if you’re buying online, make sure you familiarize yourself with the return policy.

‘Historical icons’

“Drift” (recycled wood, epoxy clay, paper pulp, fabric, graphite, gouache, watercolor pencils), by Kitty Wales, in her show “Traces,’’ at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., through Feb. 8

She writes:

“Discarded furniture and utilitarian objects represent an archive of the remembered past; the contents of your mother’s roll-top desk, table settings of a final meal shared with loved ones, or rusty tools from a workshop shed. These domestic items can serve as historical icons animating and triggering associations. They are traces of what we leave behind, and are the building blocks for this recent series of sculpture.’’

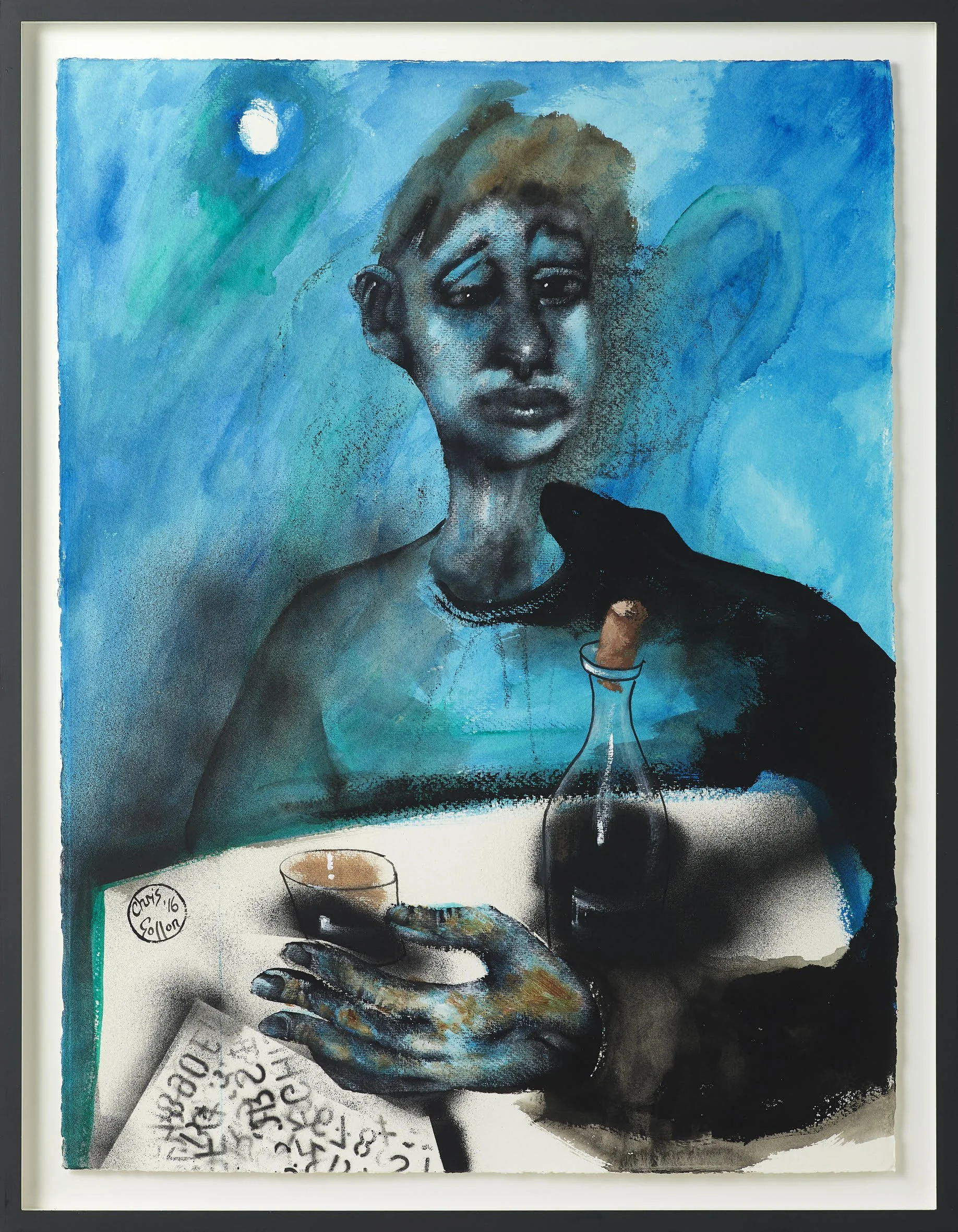

Artistic boundary crosser

“Study on Paper (1) for Gimme Some Wine’’ (acrylic on paper, 2o16), from English painter Chris Gollon’s (1953-1917) “Gimme Some Wine’’ series. See this exhibition.

And there’s a movie about him.

— Courtesy Chris Gollon Estate & IAP Fine Art.

New England Diary focuses on art from the region, but the late Mr. Gollon’s work is so exciting that we hope that some of it will be shown in America.

Mr. Gollon’s famously collaborated with musicians and songwriters, some of them American.

He said:

“Music and painting are, in my view, as with all art genres, seeking the same truth.”

Indeed, he was an artistic boundary crosser in several ways. Consider his 14 Stations of the Cross paintings commissioned by the Church of England for the Church of St John on Bethnal Green in London, though he wasn’t a practicing Christian.

Roofed with Modernism

“Roofs” (color woodblock print; block cut, 1918), by Blanche Lazzell (1878-1956), in the show “Explorations That Became a Modernist: An exhibition of Blanche Lazzell’s range beyond the white-line print,’’ at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum through Jan. 4

— Photo by Agata Storer

James T. Brett: Why New England needs the ROAD to Housing Act

Three-decker apartment building in Cambridge, Mass., built in 1916

BOSTON

Housing affordability remains one of New England’s biggest economic issues. From Worcester’s competitive rental market to small towns dealing with aging housing stock, the pressure is widespread.

That is why the Renewing Opportunity in the American Dream to Housing Act of 2025, the ROAD to Housing Act, is such a vital piece of legislation. With the bipartisan leadership of Senators Tim Scott (R.-S.C.) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), the bill was passed by the Senate with strong support from both sides of the aisle.

The bill addresses the crisis from multiple angles: increasing supply, preserving affordable units, empowering local governments, and encouraging private investment. For New England, where high costs and limited land create unique challenges, this would provide essential tools.

One highlight is the $1 billion Innovation Fund, championed by Senator Warren. This program will award competitive, flexible grants to communities expanding housing supply. Municipalities that modernize zoning or adopt creative reforms can use funds to improve infrastructure, build new homes, or upgrade essential systems.

The bill enhances the role of private investment. The Community Investment and Prosperity provisions raise the Public Welfare Investment cap for banks from 15% to 20%, giving financial institutions more flexibility to direct funds into affordable housing and community projects.

Additional reforms streamline programs and lower costs. Removing the cap on units that can be converted under the Rental Assistance Demonstration program will help maintain affordable housing. Updates to Community Development Block Grant allocations will encourage communities to remove barriers such as restrictive zoning. And revisions to the National Environmental Protection Act requirements will cut unnecessary delays in building much-needed housing.

Together, these provisions create a pathway to a healthier housing market. By combining federal leadership with local flexibility and public-private collaboration, the ROAD to Housing Act establishes the conditions for sustainable growth and stronger communities.

For New England, this isn’t just policy; it’s an economic imperative. The region’s ability to attract talent, grow businesses, and sustain communities depends on affordable, accessible housing.

The New England Council commends Senators Warren and Scott for their bipartisan leadership on this legislation. We are grateful to the Senate for passing the bill and urge the House of Representatives to follow suit. With support from builders, bankers, mayors, and nonprofits, the momentum is here. Now it is time to act.

James T. Brett is CEO and president of The New England Council.

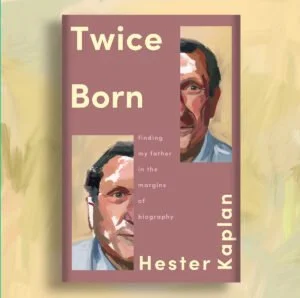

Memoirs and mysteries; using their hands

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Congratulations to the Providence writer Hester Kaplan and her husband, Michael D. Stein, M.D., for their new books.

Ms. Kaplan, a novelist and short-story writer, has just published Twice Born: Finding My Father in the Margins of Biography. This memoir revolves around her attempts to better understand her father, Justin Kaplan, the famed biographer of Mark Twain, Walt Whitman and Lincoln Steffens, and the author of other books, too; he was also a distinguished editor. I found it haunting and honest, leavened with what you might call social comedy, such as life among the self-conscious and often quietly anxious literary and academic strivers in their Cambridge, Mass., neighborhood and on Cape Cod.

Mr. Kaplan, well experienced in family tragedy as a boy, was a very complicated man, whose layers his daughter has striven with considerable success to peel off. I wonder how Mr. Kaplan, a memoirist himself, would have responded to his daughter’s book.

“I’m an obscurantist. I’m drawn to people whose lives have a certain mystery — mysteries that aren’t going to be solved, that are too sacred to be solved,’’ Mr. Kaplan told Newsweek in 1980. Hester Kaplan seems to have unraveled some mysteries about her father, but not all.

We often seem to have much more interest in trying to understand why our parents did what they did after they’re dead. I know I am still trying to figure out mine many years after their deaths. But as L.P. Hartley famously wrote for the start of his novel The Go-Between: “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there". Of course, in probing their mysteries, we’re trying to better understand who we are. To greater or lesser degrees, we are mysteries to ourselves.

xxx

For his part, Dr. Stein, a primary-care physician, health-policy researcher and prolific writer, has come out with A Living: Working-Class Americans Talk to Their Doctor. These are vignettes based on Dr. Stein’s conversations with his patients who, in a wide variety of ways, do manual labor. Many of them have had tough lives and have been victims of the harsh side of American capitalism, and some have been victims of their behavioral mistakes.

(I’m so glad that Dr. Stein included a clam digger!)

Dr. Stein notes that A Living was inspired by Studs Terkel’s 1974 best-selling book Working.

A Living presents an often poignant, sometimes jarring and sometimes funny, or at least wry, look into a part of American life that more privileged citizens would do well to know much more about, such as by reading this little book. Indeed, their ignorance about, and/or lack of interest in, these people explains some of our biggest economic, social and political problems.

Ticked off over preauthorization

Rash from Lyme disease after a tick bite.

Androscoggin River, in Brunswick, Maine, with Free Black Railroad Bridge in the foreground.

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (KFF Health News), except for image above

Leah Kovitch was pulling invasive plants in the meadow near her home in Brunswick, Maine, one weekend in late April when a tick latched onto her leg.

She didn’t notice the tiny bug until Monday, when her calf muscle began to feel sore. She made an appointment that morning with a telehealth doctor — one recommended by her health-insurance plan — which prescribed a 10-day course of doxycycline to prevent Lyme disease and strongly suggested she be seen in person. So, later that day, she went to a walk-in clinic near her home in Brunswick, Maine.

And it’s a good thing she did. Clinic staffers found another tick on her body during the same visit. Not only that, one of the ticks tested positive for Lyme, a bacterial infection that, if untreated, can cause serious conditions affecting the nervous system, heart and joints. Clinicians prescribed a stronger, single dose of the prescription medication.

“I could have gotten really ill,” Kovitch said.

But Kovitch’s insurer denied coverage for the walk-in visit. Its reason? She hadn’t obtained a referral or preapproval for it. “Your plan doesn’t cover this type of care without it, so we denied this charge,” a document from her insurance company explained.

Health insurers have long argued that prior authorization — when health plans require approval from an insurer before someone receives treatment — reduces waste and fraud, as well as potential harm to patients. And while insurance denials are often associated with high-cost care, such as cancer treatment, Kovitch’s tiny tick bite exposes how prior authorization policies can apply to treatments that are considered inexpensive and medically necessary.

The Trump administration announced this summer that dozens of private health insurers agreed to make sweeping changes to the prior-authorization process. The pledge includes releasing certain medical services from prior-authorization requirements altogether. Insurers also agreed to extend a grace period to patients who switch health plans, so that they won’t immediately encounter new preapproval rules that disrupt ongoing treatment.

Mehmet Oz, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, said during a June press conference that some of the changes would be in place by January. But, so far, the federal government has offered few specifics about which diagnostic codes tagged to medical services for billing purposes will be exempt from prior authorization — or how private companies will be held accountable. It’s not clear whether Lyme disease cases like Kovitch’s would be exempt from preauthorization.

5 Takeaways From Health Insurers’ New Pledge To Improve Prior Authorization

Dozens of health insurance companies recently pledged to improve prior authorization, a process often used to deny care. The announcement comes months after the killing of UnitedHealthcare chief executive Brian Thompson, whose death in December sparked widespread criticism about insurance denials.

Chris Bond, a spokesperson for AHIP, the health- insurance industry’s main trade group, said that insurers have committed to implementing some changes by Jan. 1. Other parts of the pledge will take longer. For example, insurers agreed to answer 80% of prior authorization approvals in “real time,” but not until 2027.

Andrew Nixon, a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, told KFF Health News that the changes promised by private insurers are intended to “cut red tape, accelerate care decisions, and encourage transparency,” but they will “take time to achieve their full effect.”

Meanwhile, some health-policy experts are skeptical that private insurers will make good on the pledge. This isn’t the first time major health insurers have vowed to reform prior authorization.

Bobby Mukkamala, president of the American Medical Association, wrote in July that the promises made by health insurers in June to fix the system are “nearly identical” to those the insurance industry put forth in 2018.

“I think this is a scam,” said Neal Shah, author of the book “Insured to Death: How Health Insurance Screws Over Americans — And How We Take It Back.”

Insurers signed on to President Trump’s pledge to ease public pressure, Shah said. Collective outrage directed at insurance companies was particularly intense following the killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in December. Oz specifically said that the pledge by health insurers was made in response to “violence in the streets.”

Shah, for one, doesn’t believe that companies will follow through in a meaningful way.

“The denials problem is getting worse,” said Shah, who co-founded Counterforce Health, a company that helps patients appeal insurance denials by using artificial intelligence. “There’s no accountability.”

Cracking the Case

Kovitch’s bill for her clinic appointment was $238, and she paid for it out-of-pocket after learning that her insurance company, Anthem, didn’t plan to cover a cent. First, she tried appealing the denial. She even obtained a retroactive referral from her primary-care doctor supporting the necessity of the clinic visit.

It didn’t work. Anthem again denied coverage for the visit. When Kovitch called to learn why, she said she was left with the impression that the Anthem representative she spoke to couldn’t figure it out.

“It was like over their heads or something,” Kovitch said. “This was all they would say, over and over again: that it lacked prior authorization.”

Jim Turner, a spokesperson for Anthem, later attributed Kovitch’s denials to “a billing error” made by MaineHealth, the health system that operates the walk-in clinic where she sought care. MaineHealth’s error “resulted in the claim being processed as a specialist visit instead of a walk-in center/urgent care visit,” Turner told KFF Health News.

He did not provide documentation demonstrating how the billing error occurred. Medical records supplied by Kovitch show that MaineHealth coded her walk-in visit as “tick bite of left lower leg, initial encounter,” and it’s not clear why Anthem interpreted that as a specialist visit.

After KFF Health News contacted Anthem with questions about Kovitch’s bill, Turner said that the company “should have identified the billing error sooner in the process than we did and we apologize for the confusion this caused Ms. Kovitch.”

Caroline Cornish, a spokesperson for MaineHealth, said this isn’t the only time that Anthem has denied coverage for patients seeking walk-in or urgent care at MaineHealth. She said Anthem’s processing rules are sometimes misapplied to walk-in visits, leading to “inappropriate denials.”

She said that these visits should not require prior authorization and Kovitch’s case illustrates how insurance companies often use administrative denials as a first response.

“MaineHealth believes insurers should focus on paying for the care their members need, rather than creating obstacles that delay coverage and risk discouraging patients from seeking care,” she said. “The system is too often tilted against the very people it is meant to serve.”

Meanwhile, in October, Anthem sent Kovitch an updated explanation of benefits showing that a combination of insurance-company payments and discounts would cover the entire cost of the appointment. She said that a company representative called her and apologized. In early November, she received her $238 refund.

But she recently found out that her annual eye appointment now requires a referral from her primary-care provider, according to new rules laid out by Anthem.

“The trend continues,” she said. “Now I am more savvy to their ways.”

Lauren Sausser is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter ( lsausser@kff.org, @laurenmsausser)

Growing together?

“Growing Couples,’’ by Maine artist Anita Loomis.

She writes:

“Painting allows me to envision what could be. With the new pieces in my ‘Couples’ series, I explore the role of love in our many kinds of relationships and connections. How do we connect and share our lives with others? Intentionally lacking facial features, these works share aspects of life that any of us might experience. Can you see yourself in the paintings?’’

‘No native plants, no native bugs’

Larvae of Swallowtail butterfly caterpillars, which feed on the leaves of the Spicebush shrub, which is native to New England.

Text excerpted from ecoRI News, but not image above

The names of two local native nurseries, both named after insects, that opened in the past few years send a pertinent message, even if one of the bugs is a hunter rather than a pollinator. The connection is obvious, or at least it should be. There are of course exemptions, but the vast majority of insects are beneficial to human survival.

If we were to take a step back from the popular bumper sticker “No Farms No Food,” “No Bugs No Food” would be the result. Another step back would give us “No Native Plants No Native Bugs.”

At that stage, we would be very hungry, or, as Emily Dutra, owner of one of those new nurseries, noted, dead. She shared that a native oak tree can “host, like, over 750 types of caterpillars. And you know what baby birds love more than anything? Nice, soft, juicy caterpillars.”