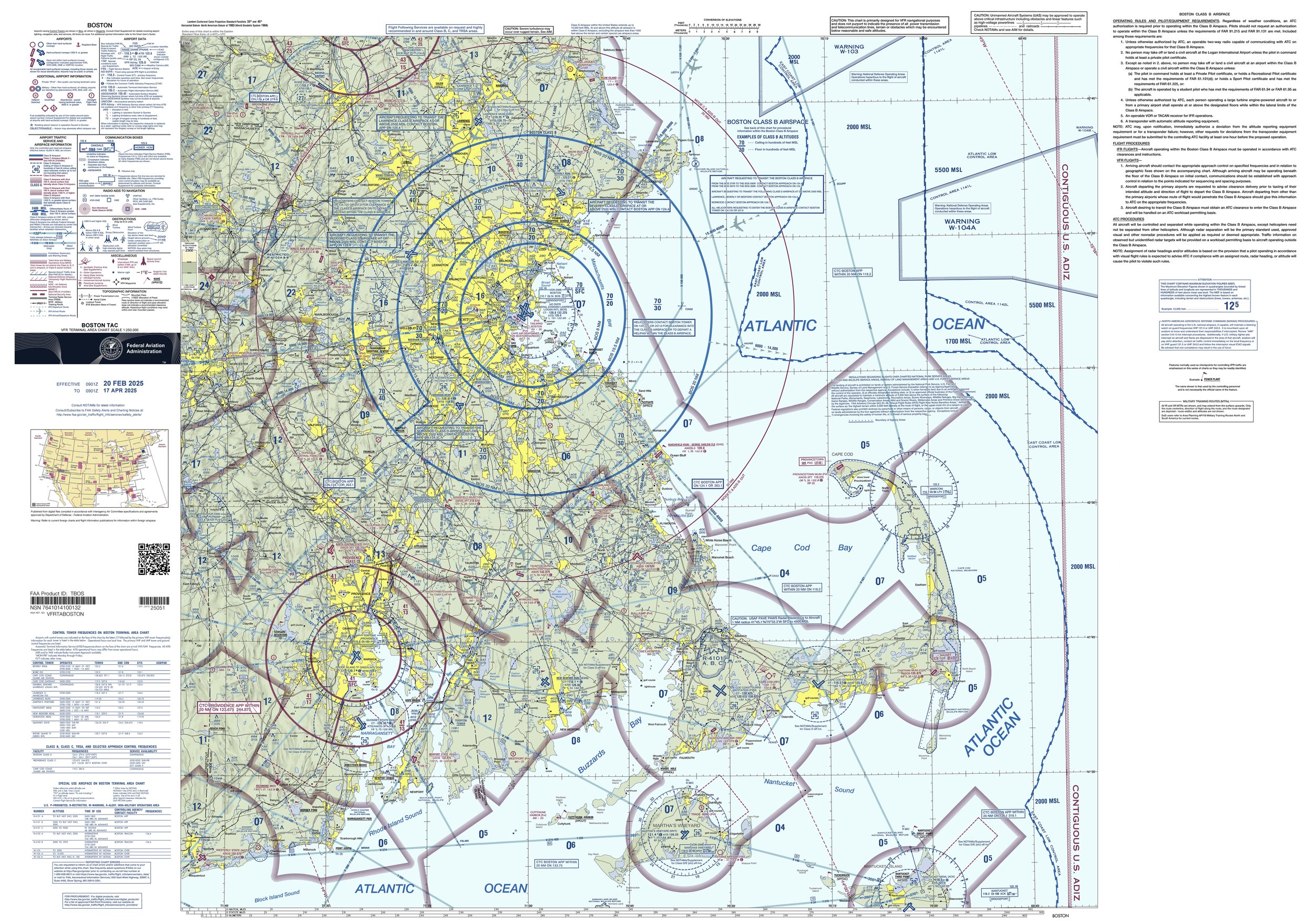

Llewellyn King: The biggest sources of stress for air-traffic controllers

Air-traffic-control zones in the southeast corner of New England.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

If you don't know about the stress that air-traffic controllers are reportedly under, then maybe you are an air-traffic controller.

The fact is that air-traffic controllers love what they do — love it and wouldn't do anything else.

The stress comes with long hours, Federal Aviation Administration bureaucracy and a general lack of recognition, not with moving airplanes safely about the sky.

Of course, I haven't interviewed every controller, but I have talked to a lot of them over the years and have been in many control towers.

Controllers love the essentiality of it. They love aviation in all its forms.

They love the man-and-machine interface, which is at the heart of modern aviation. They love the sense of being part of a great system — the power, the language, the satisfaction.

They love the trust that every pilot puts in them. It is rewarding to be trusted in anything, but more so when the price of failure is known.

Nearly everything that is true of pilots is true of controllers. At its heart, the job is about flight, arguably the greatest achievement of mankind, the fulfillment of millennia of yearning.

There is a saying often attributed to Winston Churchill that was actually said by a pilot and insurance executive in the 1930s: “Aviation in itself is not inherently dangerous. But to an even greater degree than the sea, it is terribly unforgiving of any carelessness, incapacity or neglect."

That is true both of pilots and those at the consoles on the ground, who co-fly with them.

After President Ronald Reagan fired more than 11,000 striking controllers in 1981, some of the saddest people I knew were air-traffic controllers.

They were denied the right to do the work that they loved and suffered immeasurably for that. A few were able to get work overseas, but mostly it was a light that went out and stayed out.

I ran into one former controller, working as a baggage handler. He said he just wanted to be near the action even if he couldn't go into the tower anymore and do his dream job.

My only major criticism of Reagan in this case has always been that he didn't rehire the strikers after he had won, proving that they were wrong in striking illegally and that they weren't above the law.

Reagan was often a compassionate man, but he showed the controllers no compassion. I think that if he had understood the psychological pain he had inflicted, he would have relented.

Controllers have explained to me that if a controller finds the job stressful, then he or she shouldn't be a controller.

About one-third of the candidates for controllers' school, most of whom are trained at the FAA Academy in Oklahoma City, flunk out.

It takes longer to train a controller than a pilot — maybe not to work in the cockpit of a passenger jet, but certainly to fly an aircraft, including jets. It takes at least four years of schooling, simulator and then supervised controlling to qualify to be an FAA controller. Some controllers come from the military.

There is just one movie about air-traffic control, released in 1999, Pushing Tin. It flopped at the box office but has a cult following among pilots and controllers. It is funny and accurate. Pushing tin is controllers' jargon for what they do: push airplanes around the sky.

The fabled stress, in my mind, is the adrenaline factor. It is present in air-traffic control, and it is present in the cockpit of everything that leaves the ground, from single-engine Cessnas to Boeing 777s — and in ATC facilities.

It interests me that pilots rarely mention stress. It is, however, always mentioned by people writing about or talking about air-traffic control. I would venture that the most stress that controllers deal with is the stress imposed on them by the FAA.

I will aver that in the recent and record-long government shutdown, the largest source of stress for controllers was how they were going to put food on the table and pay their bills, not the stress that they feel at the console, pushing tin and keeping flying safe. Now they are stressed about back pay.

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS and an international energy-sector consultant.

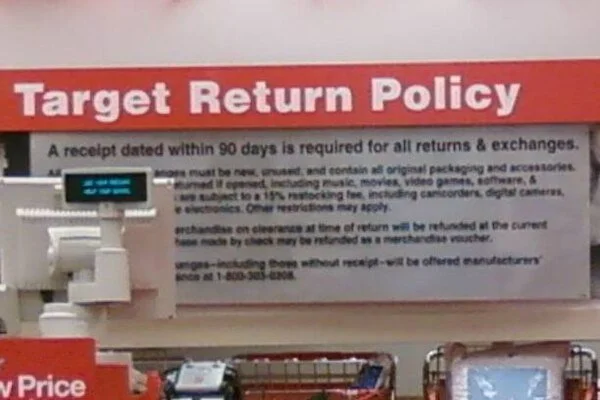

Lauren Beitelspacher: Beware stores’ new return policies

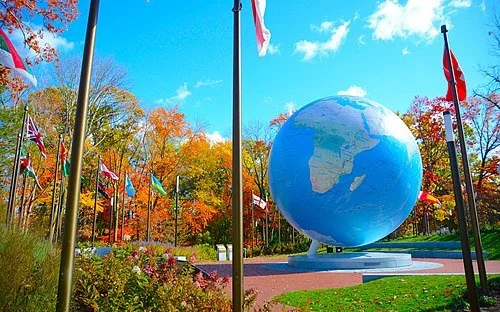

The Babson Globe, at the college’s campus, in Wellesley, Mass.

From The Conversation, except for images above.

Lauren Beitelspacher is a professor of marketing at Babson College, Wellesley Mass.

She does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

’Tis the season for giving – and that means ’tis the season for shopping. Maybe you’ll splurge on a Black Friday or Cyber Monday deal, thinking, “I’ll just return it if they don’t like it.” But before you click “buy,” it’s worth knowing that many retailers have quietly tightened their return policies in recent years.

As a marketing professor, I study how retailers manage the flood of returns that follow big shopping events like these, and what it reveals about the hidden costs of convenience. Returns might seem like a routine part of doing business, but they’re anything but trivial. According to the National Retail Federation, returns cost U.S. retailers almost US$890 billion each year.

Part of that staggering figure comes from returns fraud, which includes everything from consumers buying and wearing items once before returning them – a practice known as “wardrobing” – to more deceptive acts such as falsely claiming an item never arrived.

Returns also drain resources because they require reverse logistics: shipping, inspecting, restocking and often repackaging items. Many returned products can’t be resold at full price or must be liquidated, leading to lost revenue. Processing returns also adds labor and operational expenses that erode profit margins.

How e-commerce transformed returns

While retailers have offered return options for decades, their use has expanded dramatically in recent years, reflecting how much shopping habits have changed. Before the rise of e-commerce, shopping was a sensory experience: Consumers would touch fabrics, try on clothing and see colors in natural light before buying. If something didn’t work out, customers brought it back to the store, where an associate could quickly inspect and restock it.

Online shopping changed all that. While e-commerce offers convenience and variety, it removes key sensory cues. You can’t feel the material, test the fit or see the true color. The result is uncertainty, and with uncertainty comes higher rates of returns. One analysis by Capital One suggests that the rate for returns is almost three times higher for online purchases than for in-store purchases.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the move toward online shopping went into overdrive. Even hesitant online shoppers had to adapt. To encourage purchases, many retailers introduced or expanded generous return policies. The strategy worked to boost sales, but it also created a culture of returning.

In 2020, returns accounted for 10.6% of total U.S. retail sales, nearly double the prior year, according to the National Retail Federation data. By 2021, that had climbed to 16.6%. Unable to try things on in stores, consumers began ordering multiple sizes or styles, keeping one and sending the rest back. The behavior was rational from a shopper’s perspective but devastatingly expensive for retailers.

The high cost of convenience

Most supply chains are designed to move in one direction: from production to consumption. Returns reverse that flow. When merchandise moves backward, it adds layers of cost and complexity.

In-store returns used to be simple: A customer would take an item back to the store, the retailer would inspect the product, and, if it was in good condition, it would go right back on the shelf. Online returns, however, are far more cumbersome. Products can spend weeks in transit and often can’t be resold – by the time they arrive, they may be out of season, obsolete or no longer in their original packaging.

Logistics costs compound the problem. During the pandemic, consumers grew accustomed to free shipping. That means retailers now often pay twice: once to deliver the item and again to retrieve it.

Now, in a post-pandemic world, retailers are trying to strike a balance – maintaining customer goodwill without sacrificing profitability. One solution is to raise prices, but especially today, with inflation in the headlines, shoppers are sensitive to price hikes. The other, more common approach is to tighten return policies.

In practice, that’s taken several forms. Some retailers have begun charging small flat fees for returns, even when a customer mails an item back at their own expense. For example, the direct-to-consumer retailer Curvy Sense offers customers unlimited returns and exchanges of an item for an initial $2.98 price. Others have shortened their return windows. Over the summer, for example, beauty retailers Sephora and Ulta reduced their return window from 60 days to 30.

Many brands now attach large, conspicuous “do not remove” tags to prevent consumers from wearing items and then sending them back. And increasingly, retailers are offering store credit rather than cash or credit card refunds, ensuring that returned sales at least stay within their company.

Few retailers advertise these changes prominently. Instead, they appear quietly in the fine print of return policies – policies that are now longer, more specific and far less forgiving than they once were.

As we head into the busiest shopping season of the year, it’s worth pausing before you click “purchase.” Ask yourself: Is this something I truly want – or am I planning to return it later?

Whenever possible, shop in person and return in person. And if you’re buying online, make sure you familiarize yourself with the return policy.

‘Historical icons’

“Drift” (recycled wood, epoxy clay, paper pulp, fabric, graphite, gouache, watercolor pencils), by Kitty Wales, in her show “Traces,’’ at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., through Feb. 8

She writes:

“Discarded furniture and utilitarian objects represent an archive of the remembered past; the contents of your mother’s roll-top desk, table settings of a final meal shared with loved ones, or rusty tools from a workshop shed. These domestic items can serve as historical icons animating and triggering associations. They are traces of what we leave behind, and are the building blocks for this recent series of sculpture.’’

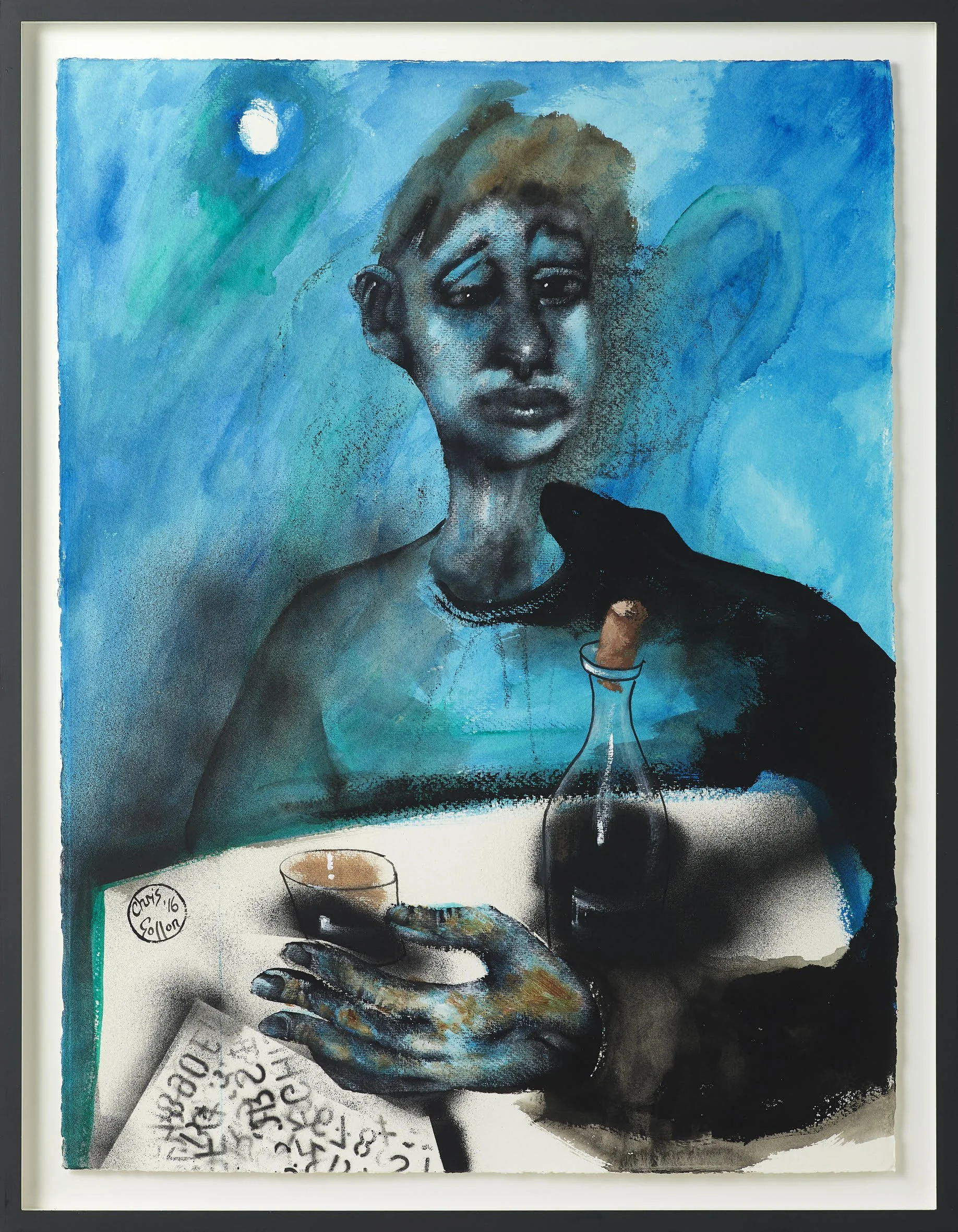

Artistic boundary crosser

“Study on Paper (1) for Gimme Some Wine’’ (acrylic on paper, 2o16), from English painter Chris Gollon’s (1953-1917) “Gimme Some Wine’’ series. See this exhibition.

And there’s a movie about him.

— Courtesy Chris Gollon Estate & IAP Fine Art.

New England Diary focuses on art from the region, but the late Mr. Gollon’s work is so exciting that we hope that some of it will be shown in America.

Mr. Gollon’s famously collaborated with musicians and songwriters, some of them American.

He said:

“Music and painting are, in my view, as with all art genres, seeking the same truth.”

Indeed, he was an artistic boundary crosser in several ways. Consider his 14 Stations of the Cross paintings commissioned by the Church of England for the Church of St John on Bethnal Green in London, though he wasn’t a practicing Christian.

Roofed with Modernism

“Roofs” (color woodblock print; block cut, 1918), by Blanche Lazzell (1878-1956), in the show “Explorations That Became a Modernist: An exhibition of Blanche Lazzell’s range beyond the white-line print,’’ at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum through Jan. 4

— Photo by Agata Storer

James T. Brett: Why New England needs the ROAD to Housing Act

Three-decker apartment building in Cambridge, Mass., built in 1916

BOSTON

Housing affordability remains one of New England’s biggest economic issues. From Worcester’s competitive rental market to small towns dealing with aging housing stock, the pressure is widespread.

That is why the Renewing Opportunity in the American Dream to Housing Act of 2025, the ROAD to Housing Act, is such a vital piece of legislation. With the bipartisan leadership of Senators Tim Scott (R.-S.C.) and Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), the bill was passed by the Senate with strong support from both sides of the aisle.

The bill addresses the crisis from multiple angles: increasing supply, preserving affordable units, empowering local governments, and encouraging private investment. For New England, where high costs and limited land create unique challenges, this would provide essential tools.

One highlight is the $1 billion Innovation Fund, championed by Senator Warren. This program will award competitive, flexible grants to communities expanding housing supply. Municipalities that modernize zoning or adopt creative reforms can use funds to improve infrastructure, build new homes, or upgrade essential systems.

The bill enhances the role of private investment. The Community Investment and Prosperity provisions raise the Public Welfare Investment cap for banks from 15% to 20%, giving financial institutions more flexibility to direct funds into affordable housing and community projects.

Additional reforms streamline programs and lower costs. Removing the cap on units that can be converted under the Rental Assistance Demonstration program will help maintain affordable housing. Updates to Community Development Block Grant allocations will encourage communities to remove barriers such as restrictive zoning. And revisions to the National Environmental Protection Act requirements will cut unnecessary delays in building much-needed housing.

Together, these provisions create a pathway to a healthier housing market. By combining federal leadership with local flexibility and public-private collaboration, the ROAD to Housing Act establishes the conditions for sustainable growth and stronger communities.

For New England, this isn’t just policy; it’s an economic imperative. The region’s ability to attract talent, grow businesses, and sustain communities depends on affordable, accessible housing.

The New England Council commends Senators Warren and Scott for their bipartisan leadership on this legislation. We are grateful to the Senate for passing the bill and urge the House of Representatives to follow suit. With support from builders, bankers, mayors, and nonprofits, the momentum is here. Now it is time to act.

James T. Brett is CEO and president of The New England Council.

Memoirs and mysteries; using their hands

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Congratulations to the Providence writer Hester Kaplan and her husband, Michael D. Stein, M.D., for their new books.

Ms. Kaplan, a novelist and short-story writer, has just published Twice Born: Finding My Father in the Margins of Biography. This memoir revolves around her attempts to better understand her father, Justin Kaplan, the famed biographer of Mark Twain, Walt Whitman and Lincoln Steffens, and the author of other books, too; he was also a distinguished editor. I found it haunting and honest, leavened with what you might call social comedy, such as life among the self-conscious and often quietly anxious literary and academic strivers in their Cambridge, Mass., neighborhood and on Cape Cod.

Mr. Kaplan, well experienced in family tragedy as a boy, was a very complicated man, whose layers his daughter has striven with considerable success to peel off. I wonder how Mr. Kaplan, a memoirist himself, would have responded to his daughter’s book.

“I’m an obscurantist. I’m drawn to people whose lives have a certain mystery — mysteries that aren’t going to be solved, that are too sacred to be solved,’’ Mr. Kaplan told Newsweek in 1980. Hester Kaplan seems to have unraveled some mysteries about her father, but not all.

We often seem to have much more interest in trying to understand why our parents did what they did after they’re dead. I know I am still trying to figure out mine many years after their deaths. But as L.P. Hartley famously wrote for the start of his novel The Go-Between: “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there". Of course, in probing their mysteries, we’re trying to better understand who we are. To greater or lesser degrees, we are mysteries to ourselves.

xxx

For his part, Dr. Stein, a primary-care physician, health-policy researcher and prolific writer, has come out with A Living: Working-Class Americans Talk to Their Doctor. These are vignettes based on Dr. Stein’s conversations with his patients who, in a wide variety of ways, do manual labor. Many of them have had tough lives and have been victims of the harsh side of American capitalism, and some have been victims of their behavioral mistakes.

(I’m so glad that Dr. Stein included a clam digger!)

Dr. Stein notes that A Living was inspired by Studs Terkel’s 1974 best-selling book Working.

A Living presents an often poignant, sometimes jarring and sometimes funny, or at least wry, look into a part of American life that more privileged citizens would do well to know much more about, such as by reading this little book. Indeed, their ignorance about, and/or lack of interest in, these people explains some of our biggest economic, social and political problems.

Ticked off over preauthorization

Rash from Lyme disease after a tick bite.

Androscoggin River, in Brunswick, Maine, with Free Black Railroad Bridge in the foreground.

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (KFF Health News), except for image above

Leah Kovitch was pulling invasive plants in the meadow near her home in Brunswick, Maine, one weekend in late April when a tick latched onto her leg.

She didn’t notice the tiny bug until Monday, when her calf muscle began to feel sore. She made an appointment that morning with a telehealth doctor — one recommended by her health-insurance plan — which prescribed a 10-day course of doxycycline to prevent Lyme disease and strongly suggested she be seen in person. So, later that day, she went to a walk-in clinic near her home in Brunswick, Maine.

And it’s a good thing she did. Clinic staffers found another tick on her body during the same visit. Not only that, one of the ticks tested positive for Lyme, a bacterial infection that, if untreated, can cause serious conditions affecting the nervous system, heart and joints. Clinicians prescribed a stronger, single dose of the prescription medication.

“I could have gotten really ill,” Kovitch said.

But Kovitch’s insurer denied coverage for the walk-in visit. Its reason? She hadn’t obtained a referral or preapproval for it. “Your plan doesn’t cover this type of care without it, so we denied this charge,” a document from her insurance company explained.

Health insurers have long argued that prior authorization — when health plans require approval from an insurer before someone receives treatment — reduces waste and fraud, as well as potential harm to patients. And while insurance denials are often associated with high-cost care, such as cancer treatment, Kovitch’s tiny tick bite exposes how prior authorization policies can apply to treatments that are considered inexpensive and medically necessary.

The Trump administration announced this summer that dozens of private health insurers agreed to make sweeping changes to the prior-authorization process. The pledge includes releasing certain medical services from prior-authorization requirements altogether. Insurers also agreed to extend a grace period to patients who switch health plans, so that they won’t immediately encounter new preapproval rules that disrupt ongoing treatment.

Mehmet Oz, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, said during a June press conference that some of the changes would be in place by January. But, so far, the federal government has offered few specifics about which diagnostic codes tagged to medical services for billing purposes will be exempt from prior authorization — or how private companies will be held accountable. It’s not clear whether Lyme disease cases like Kovitch’s would be exempt from preauthorization.

5 Takeaways From Health Insurers’ New Pledge To Improve Prior Authorization

Dozens of health insurance companies recently pledged to improve prior authorization, a process often used to deny care. The announcement comes months after the killing of UnitedHealthcare chief executive Brian Thompson, whose death in December sparked widespread criticism about insurance denials.

Chris Bond, a spokesperson for AHIP, the health- insurance industry’s main trade group, said that insurers have committed to implementing some changes by Jan. 1. Other parts of the pledge will take longer. For example, insurers agreed to answer 80% of prior authorization approvals in “real time,” but not until 2027.

Andrew Nixon, a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, told KFF Health News that the changes promised by private insurers are intended to “cut red tape, accelerate care decisions, and encourage transparency,” but they will “take time to achieve their full effect.”

Meanwhile, some health-policy experts are skeptical that private insurers will make good on the pledge. This isn’t the first time major health insurers have vowed to reform prior authorization.

Bobby Mukkamala, president of the American Medical Association, wrote in July that the promises made by health insurers in June to fix the system are “nearly identical” to those the insurance industry put forth in 2018.

“I think this is a scam,” said Neal Shah, author of the book “Insured to Death: How Health Insurance Screws Over Americans — And How We Take It Back.”

Insurers signed on to President Trump’s pledge to ease public pressure, Shah said. Collective outrage directed at insurance companies was particularly intense following the killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in December. Oz specifically said that the pledge by health insurers was made in response to “violence in the streets.”

Shah, for one, doesn’t believe that companies will follow through in a meaningful way.

“The denials problem is getting worse,” said Shah, who co-founded Counterforce Health, a company that helps patients appeal insurance denials by using artificial intelligence. “There’s no accountability.”

Cracking the Case

Kovitch’s bill for her clinic appointment was $238, and she paid for it out-of-pocket after learning that her insurance company, Anthem, didn’t plan to cover a cent. First, she tried appealing the denial. She even obtained a retroactive referral from her primary-care doctor supporting the necessity of the clinic visit.

It didn’t work. Anthem again denied coverage for the visit. When Kovitch called to learn why, she said she was left with the impression that the Anthem representative she spoke to couldn’t figure it out.

“It was like over their heads or something,” Kovitch said. “This was all they would say, over and over again: that it lacked prior authorization.”

Jim Turner, a spokesperson for Anthem, later attributed Kovitch’s denials to “a billing error” made by MaineHealth, the health system that operates the walk-in clinic where she sought care. MaineHealth’s error “resulted in the claim being processed as a specialist visit instead of a walk-in center/urgent care visit,” Turner told KFF Health News.

He did not provide documentation demonstrating how the billing error occurred. Medical records supplied by Kovitch show that MaineHealth coded her walk-in visit as “tick bite of left lower leg, initial encounter,” and it’s not clear why Anthem interpreted that as a specialist visit.

After KFF Health News contacted Anthem with questions about Kovitch’s bill, Turner said that the company “should have identified the billing error sooner in the process than we did and we apologize for the confusion this caused Ms. Kovitch.”

Caroline Cornish, a spokesperson for MaineHealth, said this isn’t the only time that Anthem has denied coverage for patients seeking walk-in or urgent care at MaineHealth. She said Anthem’s processing rules are sometimes misapplied to walk-in visits, leading to “inappropriate denials.”

She said that these visits should not require prior authorization and Kovitch’s case illustrates how insurance companies often use administrative denials as a first response.

“MaineHealth believes insurers should focus on paying for the care their members need, rather than creating obstacles that delay coverage and risk discouraging patients from seeking care,” she said. “The system is too often tilted against the very people it is meant to serve.”

Meanwhile, in October, Anthem sent Kovitch an updated explanation of benefits showing that a combination of insurance-company payments and discounts would cover the entire cost of the appointment. She said that a company representative called her and apologized. In early November, she received her $238 refund.

But she recently found out that her annual eye appointment now requires a referral from her primary-care provider, according to new rules laid out by Anthem.

“The trend continues,” she said. “Now I am more savvy to their ways.”

Lauren Sausser is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter ( lsausser@kff.org, @laurenmsausser)

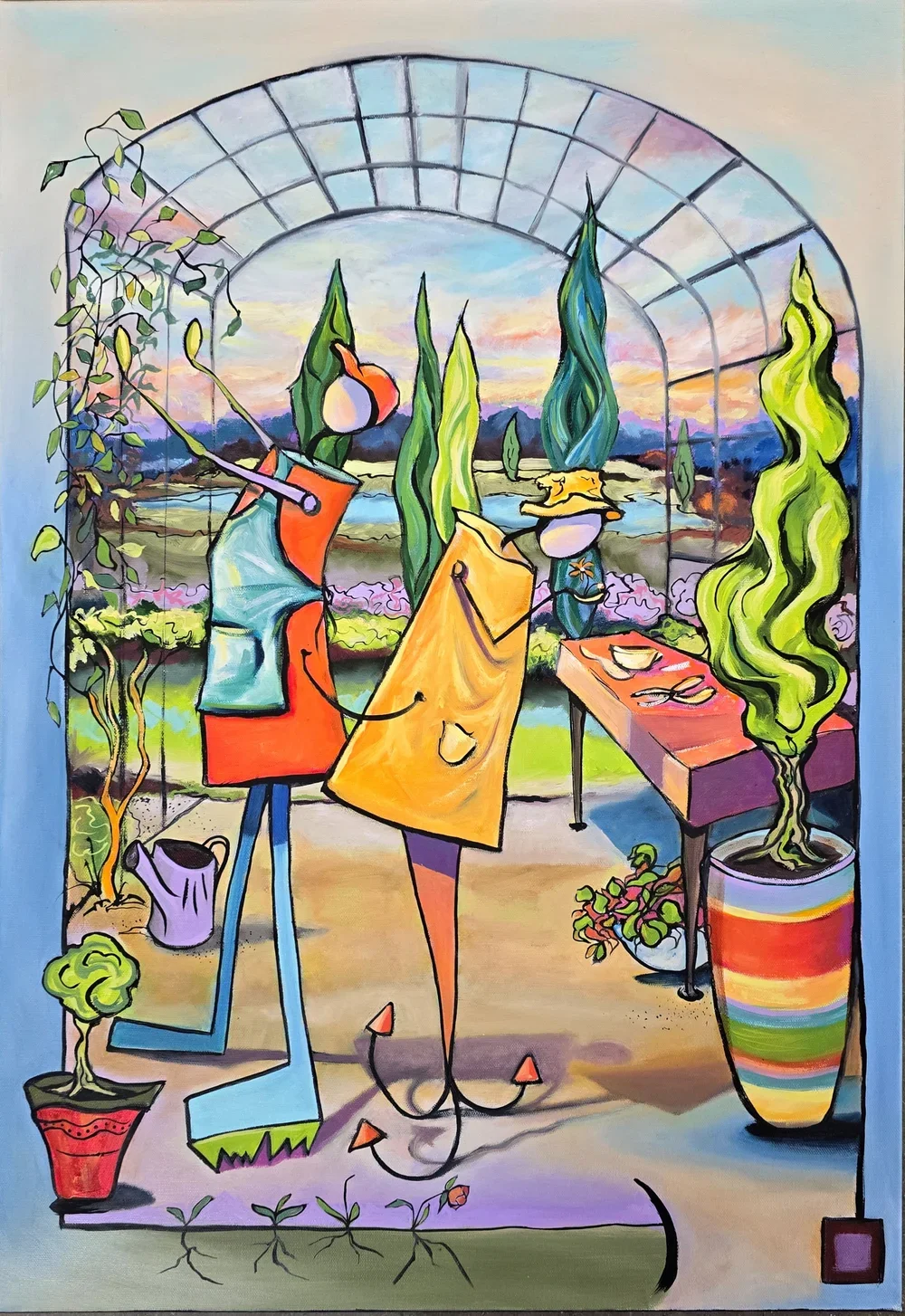

Growing together?

“Growing Couples,’’ by Maine artist Anita Loomis.

She writes:

“Painting allows me to envision what could be. With the new pieces in my ‘Couples’ series, I explore the role of love in our many kinds of relationships and connections. How do we connect and share our lives with others? Intentionally lacking facial features, these works share aspects of life that any of us might experience. Can you see yourself in the paintings?’’

‘No native plants, no native bugs’

Larvae of Swallowtail butterfly caterpillars, which feed on the leaves of the Spicebush shrub, which is native to New England.

Text excerpted from ecoRI News, but not image above

The names of two local native nurseries, both named after insects, that opened in the past few years send a pertinent message, even if one of the bugs is a hunter rather than a pollinator. The connection is obvious, or at least it should be. There are of course exemptions, but the vast majority of insects are beneficial to human survival.

If we were to take a step back from the popular bumper sticker “No Farms No Food,” “No Bugs No Food” would be the result. Another step back would give us “No Native Plants No Native Bugs.”

At that stage, we would be very hungry, or, as Emily Dutra, owner of one of those new nurseries, noted, dead. She shared that a native oak tree can “host, like, over 750 types of caterpillars. And you know what baby birds love more than anything? Nice, soft, juicy caterpillars.”

Take cover

“The Cloud” (circa 1930, oil on canvas), by John Steuart Curry (1887-1946), at Southern Vermont Arts Center, Manchester.

‘Dissolving the boundaries’

From Eastefania Puerta's show “Laughing Death Drive’’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Conn., to Jan. 11, 2026.

The museum says:

“Born in Colombia and raised in East Boston, Puerta channels her experience growing up undocumented into a practice that redefines categorization—dissolving the boundaries between alien and natural, comforting and threatening, spoken and withheld. Influenced by literature, mythology, and psychoanalysis, she explores themes of shapeshifting and transformation, reflecting on what is gained or lost through cultural and material translation.’’

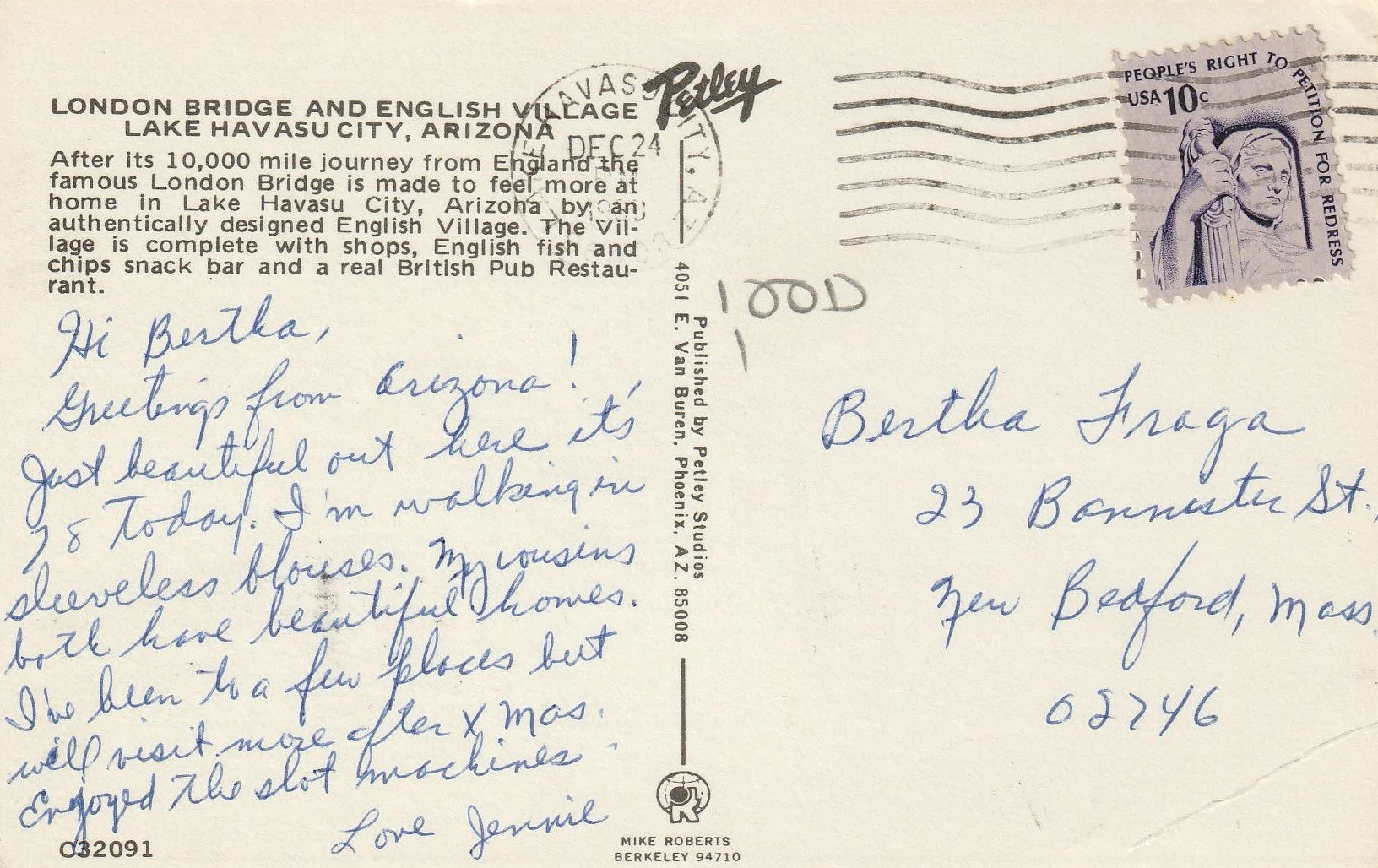

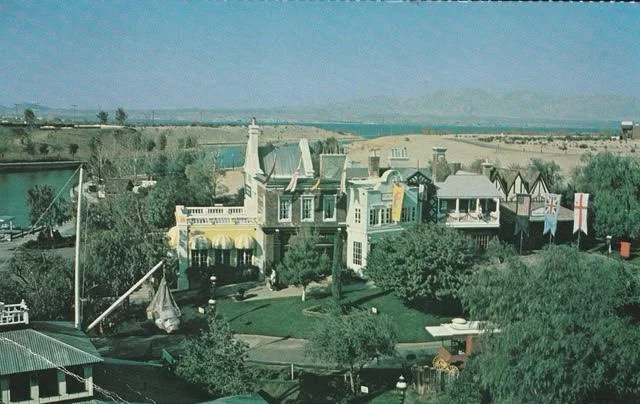

William Morgan: An Arizona developer’s dream of London Bridge in the desert

On Christmas Eve in the late 1970s, Jennie wrote a postcard to her friend Bertha Fraga back home, in New Bedford, Mass. There’s a bit of Schadenfreude on Jennie’s part: Bertha’s address is a triple decker in a run-down area just a block from Interstate Route 195.

As opposed to gray skies and snow flurries in the old whaling port, it is “Just beautiful out here it’s 78 today. I’m walking in sleeveless blouses. Both my cousins have beautiful homes.”

Jennie probably visited the Grand Canyon while on her trip, but her postmark puts her at Arizona’s second-most-popular tourist spot, London Bridge.

The Lake Havasu City bridge was purchased a decade before by a local businessman for $2.5 million, spending another $7 million to get the famous l830s landmark shipped from the Thames to the lake and reconstructed. (The Lord Mayor of London traveled to lay the cornerstone.)

London Bridge in Lake Havasu City, Ariz.

While undoubtedly an urban myth, there was some speculation that the Arizona developer believed that he was purchasing the much larger and far more ornate Tower Bridge. As it was, only the external granite blocks of London Bridge were taken to the Arizona site, next to the Colorado River, where they were attached to a new steel and concrete frame.

English Village at Lake Havasu City.

In trying to increase the visitor appeal of his planned city, the developer constructed “an authentically designed English village” to make the London Bridge “feel more at home.” Looking like a movie set from an old Western, the village boasted an “English fish and chips snack bar and a real British Pub Restaurant.”

Not surprisingly, the village expanded, as, promoters say, “local entrepreneurs and dreamers saw its potential and reimagined the space as a hub of family fun and entertainment.” Hit this link.

The Hog in Armor pub is now a microbrewery. As official Lake Havasu PR asserts, “the English Village remains a beloved destination for making memories … and feeling the magic of reinvention done right.”

Jennie may have been dazzled by the desert sun and the English Village’s cute shops, but score points to Bertha for living in an architecturally rich town with real, unmanufactured history.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural critic and historian and photographer. He has been contributing stories on New England’s quirky heritage to New England Diary for years. His book The Almighty Wall is about architect Henry Vaughan, who designed the original building of the Whaling Museum in New Bedford.

Nicholas Jacobs: Maine’s hyper-controversial Graham Platner in context

Graham Platner

Nicholas Jacobs is Goldfarb Family Distinguished Chair in American Government at Colby College, Waterville, Maine.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

WATERVILLE, Maine

From The Conversation, except for images above.

Every few years, Democrats try to convince themselves they’ve found the one – a candidate who can finally speak fluent rural, who looks and sounds like the voters they’ve lost.

In 2024, that hope was pinned on Tim Walz, the flannel-wearing, “Midwestern nice” governor whose small-town roots were supposed to unlock the rural Midwest for a Harris–Walz victory.

Now those expectations have migrated to New England, onto Graham Platner – the tattooed veteran and oyster farmer from Maine who swears from the stump, wears sweatshirts instead of suits, and, some believe, could be the party’s blue-collar savior against U.S. Sen. Susan Collins, the Republican incumbent running her sixth campaign for the Senate.

I study rural politics and live in rural Maine. I’m skeptical whether Platner can reach the independents and rural moderates Democrats need. But I also see why people think he might: He’s speaking to grievances that are real, measurable and decades in the making.

Platner represents Democrats’ anxieties about class and geography – a projection of the authenticity they hope might reconcile their national brand with rural America. On paper, he’s the kind of figure they imagine can bridge the divide: a plainspoken Mainer.

But his story cuts both ways. He’s the grandson of a celebrated Manhattan architect; his father is a lawyer, and his mother is a restaurateur whose business caters to summer tourists. He attended the elite Hotchkiss School.

It’s a life of silver spoons and salt air. That tension mirrors the Democratic party itself, led and funded by urban professionals who are increasingly aware of just how far they strayed from their working-class roots.

If Platner is to prevail, he must assemble a coalition that expands beyond what the party has become – concentrated in urban and coastal enclaves, financed nationally and culturally distant from much of rural America.

Yet Platner’s immediate hurdle isn’t rural Maine at all. It is the Democratic primary, and those voters do not live where his campaign imagery is set.

Opportunity zone

In 2024, nearly 6 in 10 registered Democrats in Maine lived south of the state capital Augusta. That part of the state would not constitute an urban metropolis anywhere else in the U.S., but it is a drastically different world than the one Platner is fighting for.

The party’s gravitational center sits in Cumberland and York counties: Greater Portland and the southern coastal strip. That electorate is more educated, affluent and urban than the state as a whole, clustered in Portland’s walkable neighborhoods, college towns such as Brunswick and artsy coastal communities that swell with summer tourists.

Southern Maine – closer in feel to Boston’s suburbs than to the paper mills and potato fields up north – is where Democrats are already strong. Collins’s vulnerability lies instead among independents in small cities and towns, in deindustrialized and rural counties drifting rightward for two decades.

The 2020 U.S. Senate race – one that nearly every analyst, myself included, thought Collins was doomed to lose to Democrat Sara Gideon – makes that reality clear.

Collins outperformed Donald Trump in every county. She built commanding margins in rural Maine, offsetting Democratic gains in Portland and the southern coast. Her real breakthrough came in the kinds of small towns where Trump lost and she won or closed the margin: Ellsworth, Brewer, Machias, Gardiner and Winterport.

Those former mill towns and service hubs once anchored the Maine Democratic Party. They’re home to exactly the kinds of voters who, in principle, might give someone like Platner a hearing: not deeply ideological, modestly skeptical of both parties and wary of national polarization.

But they are also the voters least represented in the Democratic primary electorate or the donor class fueling Platner’s campaign.

Doing it as a Democrat

According to the most recent Federal Election Commission figures, only about 12% of Platner’s haul has even come from inside Maine. The nationalization of campaign finance is becoming more common for U.S. Senate candidates.

But there are two differences worth noting.

Platner’s in-state share is higher and more geographically diffuse than Gideon’s 2020 campaign. Then, in what became Maine’s most expensive Senate race, just 4% of Gideon’s war chest was homegrown. Most of that Maine money was heavily concentrated in Portland and the southern coastal corridor.

While 64% of Gideon’s Maine total fundraising amount came from the three southernmost counties, 88% of Platner’s current in-state funding is from outside the urban-suburban core of southern Maine.

That divergence matters. It suggests that while Platner’s campaign is still fueled by national money, its local base – however small – extends beyond the usual Portland orbit.

And there is a reason Platner’s message has not been dead on arrival.

The economic populism he’s advancing speaks directly to the material frustrations many rural residents express – frustration with corporate consolidation, rising costs and the feeling that prosperity never reaches their communities.

The 2024 Cooperative Election Study shows that rural independents and moderates often share progressive instincts on precisely these issues:

Large majorities of rural, moderate/independent New Englanders support higher taxes on the wealthy and expanded health coverage. Platner is emphasizing those issues – corporate power, health costs, infrastructure, wages – where the urban–rural divide is narrowest.

Platner may be closing that gap. In an October 2025 survey, 58% of likely Democratic primary voters named him as their first choice for the 2026 Senate nomination. While that support has likely changed in the aftermath of two controversies – his chest tattoo that resembled a Nazi icon and recent posts on Reddit, including one in which he says rural people “actually are” “stupid” and “racist” – that poll’s most notable finding is the consistency of support across income and education levels.

Still, while his message may bridge income and education, the biggest obstacle facing Platner is the simplest one: He’s trying to do all of this as a Democrat.

Hearing, not speaking

Being anchored in metropolitan and professional networks far removed from rural life shapes not only what Democrats stand for but how they speak, focusing on moral and cultural commitments that resonate nationally but feel abstract in smaller, locally based communities.

That’s why even an economically resonant message struggles once it meets the national brand.

Rural independents and moderates often agree with Democrats on taxes, health care and wages. Those alignments fade when policy is framed through the institutions and moral language of a party many no longer see as compatible with rural ways of living.

It’s not clear yet how Platner will respond on issues that don’t poll well in rural Maine – environmental regulation, gun control or immigration – where loyalty to the national agenda has undone many would-be reformers before him.

And that schism is not because rural voters misunderstand their “self-interest” or because racial dog whistles have led them astray. It is hostility toward a party that, with rare exception, sees the future as something rural America must adapt to, not something it should help define.

That is the danger of treating biography as the solution to a decades-long realignment. Platner might be as close as Democrats have come in years to a candidate who can talk credibly to rural voters about power, place and policy. But he still has to do it while wearing the “scarlet D” – the weight of a party brand built over generations.

Whether he wins or loses, his campaign already points to a deeper question: Can Democrats do more than rent rural authenticity? Put more bluntly, the real test is not whether Platner can speak to rural Maine, it is whether his party can finally learn to hear it.

Time to clear out?

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Does New England have more in common with Ontario, Quebec and the Maritime Provinces than with, in particular, the Deep South? I’d say yes.

Which gets me to Colin Woodard’s new book, Nations Apart: How Clashing Regional Cultures Shattered America.

The book’s most interesting themes are how old and entrenched these cultural, political and economic differences are, and that they’re unlikely to be bridged. Knowing the backgrounds of those who took over these regions from the Native Americans is crucial in understanding these “nations.’’ Think of New England’s Puritans, New York’s Dutch and Appalachia’s Scotch-Irish. Mr. Woodard eloquently discusses why the richest, and what you might call the most “civilized’’ and humane, parts of the U.S. do so well and Appalachia and the Deep South so poorly.

Maybe it’s time to get it over with and split up the country.

After ‘civilization’

“Rewilding’’(acrylic on canvas), by Marli Thibodeau, in her show “Art & Wine, at Gallery Sitka, Newport, R.I., through Dec. 12.

Chris Powell: Designed to prohibit housing affordability

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Perhaps taking a hint from socialist Democrat Zohran Mamdani's successful campaign for mayor of New York City, whose slogan was “A city we can afford," politicians in both parties in Connecticut are taking “affordability" for their own platforms.

Some Connecticut Democrats, including Gov. Ned Lamont, have even attributed their party's success in this month's municipal elections to a supposed commitment to affordability. This is laughable. Far more votes were probably pushed toward the Democrats by the political chaos in Washington than by any achievement in “affordability" in Connecticut, though the six-week partial shutdown of the federal government was an entirely Democratic stunt, not President Trump's doing.

Yes, Connecticut's Democratic state administration hasn't raised taxes much lately, but municipal property taxes still go up because state law and policy determine much of how municipalities spend their money. These days there's not much difference between state and municipal finance.

Greenwich state Sen. Ryan Fazio, a candidate for the Republican nomination for governor next year, pressed the “affordability" theme in response to Lamont's declaration of candidacy for a third term.

“Governor Lamont's first eight years in office," Fazio said, “have seen Connecticut's electricity rates rise to the third-highest in the nation, and our economic growth plummet to fourth worst in the country. Families are struggling to make ends meet, while people and jobs are leaving our state. … I am running for governor to make our state more affordable and safe and create opportunities for all."

Connecticut's increasing unaffordability has been caused to a great extent by the explosion of federal spending and debt, for which the state's members of Congress, all Democrats, share responsibility.

But much of Connecticut's unaffordability is also caused by the state's own law and policy. Indeed, state law and policy virtually prohibit affordability by preventing ordinary efficiency in government, and affordability will never be achieved if this isn't spelled out.

For example, Connecticut didn't enact collective bargaining for government employees and binding arbitration for their union contracts in pursuit of affordability. Collective bargaining and binding arbitration for government employees had the effect of driving up government's costs, relieving elected officials of difficult responsibility, and sustaining a powerful special interest that serves as the army of the majority party, the Democrats.

These laws forbid ordinary democratic control and accountability in public administration.

Connecticut didn't enact its minimum budget requirement for school systems in pursuit of affordability. The minimum budget requirement, which virtually prohibits economizing in school systems even if student enrollment falls substantially, was enacted to ensure that any financial savings in schools would be transferred to school employees, particularly teachers, rather than refunded to taxpayers.

Nor did Connecticut enact its “public benefits charges" -- essentially taxes on electricity -- to make life in the state more affordable but to conceal the costs of welfare and “green" energy programs in electricity bills so people would blame the electric utilities for electricity's high cost, though the utilities, at the command of state law, stopped generating electricity years ago and now only distribute it.

At least Republican state legislators, a small minority in the General Assembly, recently made an issue of the “public benefits charges" and the majority Democrats found them hard to defend, so some were removed from electric bills. But they were not eliminated. Instead state government now is paying for the “public benefits" with bond money, which will cost state residents even more in the long run.

The “public benefits charges" were an easy target. The special interests dependent on them, welfare recipients and self-styled environmentalists, are not so influential. But collective bargaining and binding arbitration for state and local government employees have huge special-interest constituencies, as does the minimum budget requirement for schools.

Those anti-affordability laws are far more expensive than the “public benefits charges," and no politician is likely to criticize them, though there will be little affordability in the state until they are repealed or reduced in scope.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

When the Red States attacked

“Our Banner in the Sky” (1861 oil painting), by Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900).

This painting by Church, a Connecticut native, was his political statement in defense of the Union when the Confederate attacked Fort Sumter, S.C., in April 1861, launching the Civil War. The vivid orange sky represents the Union flag with a bare tree stick as the flagpole.

Sustainable-fishing project off New Hampshire

AquaFort structure off the New Hampshire coast.

Edited from a New England Council report

The University of New Hampshire is advancing its AquaFort seafood system in producing more local fish at its facility off the coast of New Castle, N.H. AquaFort is part of UNH’s Center fo Sustainable Seafood Systems.

The 28 by 52-foot floating structure raises steelhead trout in a system that naturally filters waste through kelp and mussels, creating a sustainable cycle that helps both the environment and fishermen. Researchers believe that it could bring more stability to the local fishing business and allow for a much smaller human footprint.