Lunacy in the Litchfield Hills?

From “What Lurks on Channel X,’’ by Rob Zombie, at the Morrison Gallery, Kent, Conn., through Nov. 16.

Justin Reich: History warns us to beware of AI hype for schools

AI-generated draft article getting nominated for speedy deletion under G15 criteria.

From The Conversation, except for image above

Justin Reich is a professor of Digital Media at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

He has received funding from Google, Microsoft, Apple, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Chan/Zuckerberg Initiative, the Hewlett Foundation, education publishers, and other organizations involved in technology and schools.

CAMBRIDGE, Mass.

American technologists have been telling educators to rapidly adopt their new inventions for over a century. In 1922, Thomas Edison declared that in the near future, all school textbooks would be replaced by film strips, because text was 2% efficient, but film was 100% efficient. Those bogus statistics are a good reminder that people can be brilliant technologists, while also being inept education reformers.

I think of Edison whenever I hear technologists insisting that educators have to adopt artificial intelligence as rapidly as possible to get ahead of the transformation that’s about to wash over schools and society.

At MIT, I study the history and future of education technology, and I have never encountered an example of a school system – a country, state or municipality – that rapidly adopted a new digital technology and saw durable benefits for their students. The first districts to encourage students to bring mobile phones to class did not better prepare youth for the future than schools that took a more cautious approach. There is no evidence that the first countries to connect their classrooms to the Internet stand apart in economic growth, educational attainment or citizen well-being.

New education technologies are only as powerful as the communities that guide their use. Opening a new browser tab is easy; creating the conditions for good learning is hard.

It takes years for educators to develop new practices and norms, for students to adopt new routines, and for families to identify new support mechanisms in order for a novel invention to reliably improve learning. But as AI spreads through schools, both historical analysis and new research conducted with K-12 teachers and students offer some guidance on navigating uncertainties and minimizing harm.

Wrong and overconfident before

I started teaching high-school history students how to search the web in 2003. At the time, experts in library and information science developed a pedagogy for Web evaluation that encouraged students to closely read websites looking for markers of credibility: citations, proper formatting, and an “about” page.

We gave students checklists such as the CRAAP test – currency, reliability, authority, accuracy and purpose – to guide their evaluation. We taught students to avoid Wikipedia and to trust websites with .org or .edu domains over .com domains. It all seemed reasonable and evidence-informed at the time.

The first peer-reviewed article demonstrating effective methods for teaching students how to search the web was published in 2019. It showed that novices who used these commonly taught techniques performed miserably in tests evaluating their ability to sort truth from fiction on the web. It also showed that experts in online information evaluation used a completely different approach: quickly leaving a page to see how other sources characterize it. That method, now called lateral reading, resulted in faster, more accurate searching. The work was a gut punch for an old teacher like me. We’d spent nearly two decades teaching millions of students demonstrably ineffective ways of searching.

Today, there is a cottage industry of consultants, keynoters and “thought leaders” traveling the country purporting to train educators on how to use AI in schools. National and international organizations publish AI literacy frameworks claiming to know what skills students need for their future. Technologists invent apps that encourage teachers and students to use generative AI as tutors, as lesson planners, as writing editors, or as conversation partners. These approaches have about as much evidential support today as the CRAAP test did when it was invented.

There is a better approach than making overconfident guesses: rigorously testing new practices and strategies and only widely advocating for the ones that have robust evidence of effectiveness. As with web literacy, that evidence will take a decade or more to emerge.

But there’s a difference this time. AI is what I have called an “arrival technology.” AI is not invited into schools through a process of adoption, like buying a desktop computer or smartboard – it crashes the party and then starts rearranging the furniture. That means that schools have to do something. Teachers feel this urgently. Yet they also need support: Over the past two years, my team has interviewed nearly 100 educators from across the U.S., and one widespread refrain is “don’t make us go it alone.”

3 strategies for prudent path

While waiting for better answers from the education science community, which will take years, teachers will have to be scientists themselves. I recommend three guideposts for moving forward with AI under conditions of uncertainty: humility, experimentation and assessment.

First, regularly remind students and teachers that anything schools try – literacy frameworks, teaching practices, new assessments – is a best guess. In four years, students might hear that what they were first taught about using AI has since proved to be quite wrong. We all need to be ready to revise our thinking.

Second, schools need to examine their students and curriculum, and decide what kinds of experiments they’d like to conduct with AI. Some parts of your curriculum might invite playfulness and bold new efforts, while others deserve more caution.

In our podcast “The Homework Machine,” we interviewed Eric Timmons, a teacher in Santa Ana, Calif., who teaches elective filmmaking courses. His students’ final assessments are complex movies that require multiple technical and artistic skills to produce. An AI enthusiast, Timmons uses AI to develop his curriculum, and he encourages students to use AI tools to solve filmmaking problems, from scripting to technical design. He’s not worried about AI doing everything for students: As he says, “My students love to make movies. … So why would they replace that with AI?”

It’s among the best, most thoughtful examples of an “all in” approach that I’ve encountered. I also can’t imagine recommending a similar approach for a course like ninth grade English, where the pivotal introduction to secondary school writing probably should be treated with more cautious approaches.

Third, when teachers do launch new experiments, they should recognize that local assessment will happen much faster than rigorous science. Every time schools launch a new AI policy or teaching practice, educators should collect a pile of related student work that was developed before AI was used during teaching. If you let students use AI tools for formative feedback on science labs, grab a pile of circa-2022 lab reports. Then, collect the new lab reports. Review whether the post-AI lab reports show an improvement on the outcomes you care about, and revise practices accordingly.

Between local educators and the international community of education scientists, people will learn a lot by 2035 about AI in schools. We might find that AI is like the web, a place with some risks but ultimately so full of important, useful resources that we continue to invite it into schools.

Or we might find that AI is like cellphones, and the negative effects on well-being and learning ultimately outweigh the potential gains, and thus are best treated with more aggressive restrictions.

Everyone in education feels an urgency to resolve the uncertainty around generative AI. But we don’t need a race to generate answers first – we need a race to be right.

‘Just the questions’

“Sunk” (acrylic on canvas), by Claudia Doherty, in her show “Fragments of Her,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Nov. 6-30.

She says:

“What’s on my mind when I paint and when I think about painting is a woman alone. Did she slip away from him or maybe run? Is she relishing solitude or sunken in loneliness? Would she startle if approached? Does she want to crash the waves, trudge through the bog, lie down in the reedy marsh? Is she gutted by a loss, sick with want, motherless, black and blue? I want to see all of this in my paintings, not the answers though, just the questions.”

Small-town energy

Consider Hatch House (built in 1748 but obviously much changed since then), in Falmouth, Mass.

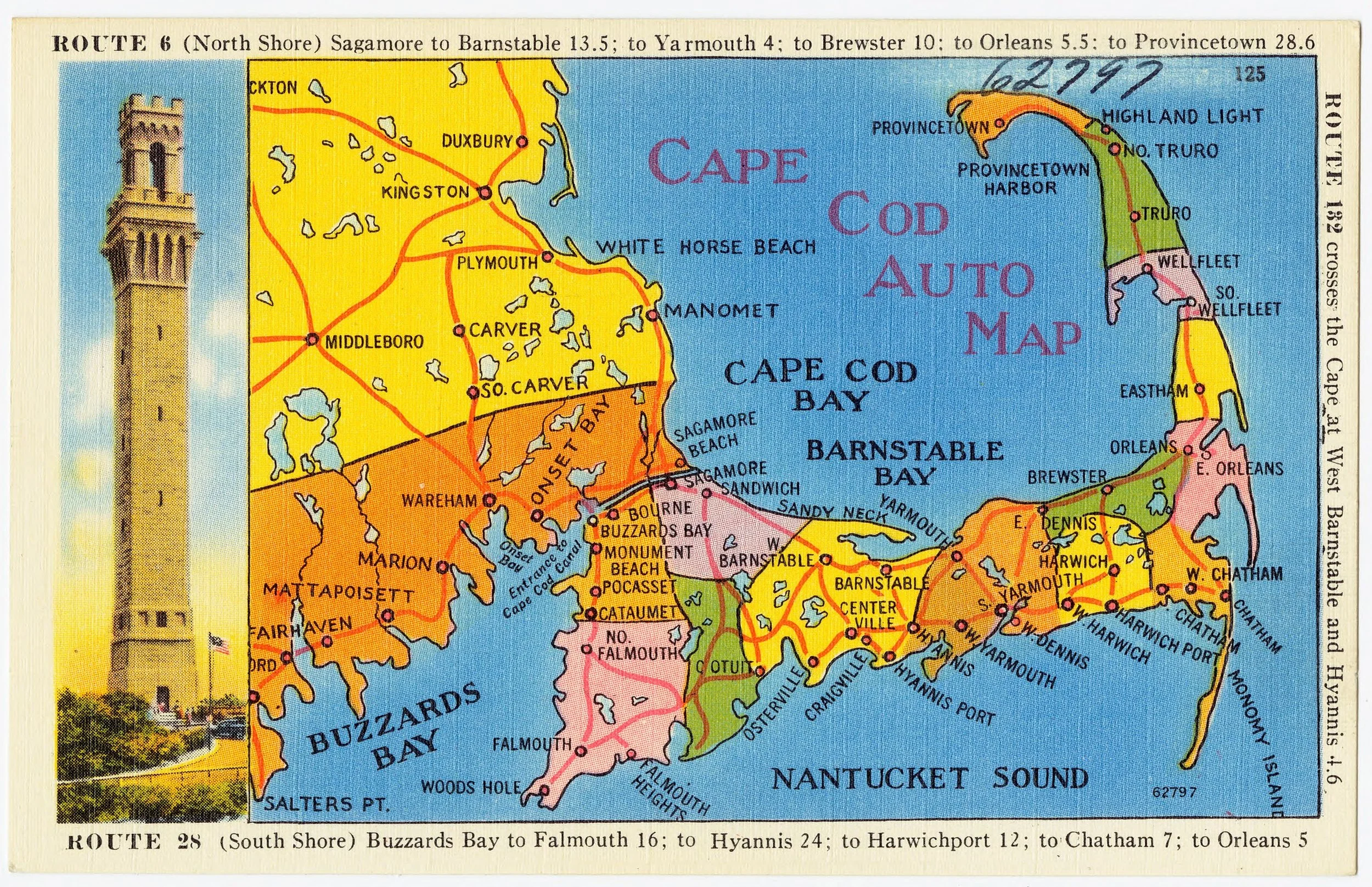

Cape Cod Auto Map, 1930s–40s postcard by Tichnor Bros. of Boston.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I made a recent road trip was to Falmouth, Mass., on the Cape, where I did a little more historical research, mostly about the 19th Century in that town, where many of my ancestors lived. I was struck again by the energy of town leaders, then, in business and civic life. They’d start up a wide range of businesses, from salt collection, to guano processing (for fertilizers), to boat building, to raising sheep for wool, a major sector in New England at the time as textile mills popped up. When one business didn’t pan out they’d go on to the next at a good clip. They were remarkably handy at fixing things, both business plans and equipment. And they did this at a time when transportation was much more difficult than it is now.

Consider that members of the local Butler family who owned the town’s monopolistic town general store, found it easier to ship by boat from New York City some stuff to provision the store than to get it from the much closer Boston area, which often required, before the trains came in, transporting stuff via the sometimes perilous route around Cape Cod in pre-canal days.

While being energetic small-town capitalists, many Falmouth folks were notably civic-minded, of course sometimes out of enlightened self-interest. There seemed to be no dearth of men (in those pre-women’s suffrage days) willing to run for selectman, state representative or other political posts and to promote the construction of schools and other public facilities, as well as churches. And they’d get into heated issues such as by signing petitions to abolish slavery and holding public meetings on that and other matters.

Still, mixed with all this energy, as I can tell from their letters, were fatalism and melancholy, which they seem to have passed on to their descendants.

It was a very different world, of course, but there are some lessons to be learned about building successful communities from Falmouth.

I was struck by how busy downtown Falmouth seemed last week, even though the prime summer people and tourist season ended weeks ago. Half a century ago, it would have been much quieter at this time of year. Maybe that autumns are getting warmer has something to do with it.

And, oh dear!

The Trump regime, whose greatest enthusiasm seems to be to stick it to its real or perceived adversaries, has paused $11 billion in funding for infrastructure projects in some Democratic Party-led cities, including Boston, and put into some doubt the $600 million that the Feds had pledged to help pay to replace the two decaying highway bridges over the Cape Cod Canal, which were built the ‘30’s.

Meanwhile, $172 million in taxpayer money will go to buy two Gulfstream jets for the use of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and her top assistants.

Ms. Noem, as does her boss, loves to flaunt luxury. Some may recall her $50,000 gold Rolex wristwatch; the origin of the money to buy it remains something of a mystery.

Anyway, the public be damned! Some $300 million is being spent to illegally demolish the East Wing of the White House and rebuild it for a huge ballroom where the Orange Oligarch can hold court. But don’t worry, the money is coming from private donors. You can bet that most of them seek special access to the king.

New England’s huge financial-services sector

Boston Financial District

Industry giant Fidelity Investments’ headquarters, at 245 Summer St., Boston.

Read The New England Council’s report on the region’s financial-services industry here.

Llewellyn King: Our dichotomous America

One year after the 2016 election that delivered Donald Trump his first term, American Facebook users on the right and left shared very few common interests.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

We live in an age of dichotomy in America.

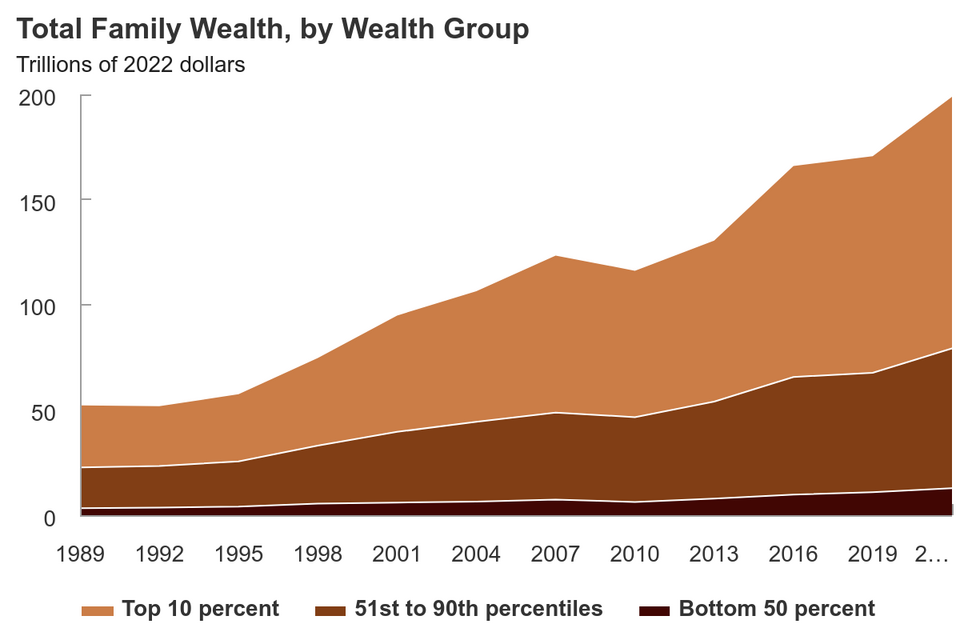

The rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer.

We have more means of communication, but there is a pandemic of loneliness.

We have unprecedented access to information, but we seem to know less, from civics to the history of the country.

We are beginning to see artificial intelligence displacing white-collar workers in many sectors, but there is a crying shortage of skilled workers, including welders, electricians, pipe fitters and ironworkers.

If your skill involves your hands, you are safe for now.

New data centers, hotels and mixed-use structures, factories and power plants are being delayed because of worker shortages. But the government is expelling undocumented immigrants, hundreds of thousands who have skills.

Thoughts about dichotomy came to me when Adam Clayton Powell III and I were interviewing Hedrick Smith, a journalist in full: a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter and editor, an Emmy Award-winning producer/correspondent and a bestselling author.

We were talking with Smith on White House Chronicle, the weekly news and public affairs program on PBS for which I serve as executive producer and co-host.

The two dichotomies that struck me were Smith's explanation of the decline of the middle class as the richest few rise, and how Congress has drifted into operating more like the British Parliament with party-line votes than the body envisaged by The Founders.

Echoing Benjamin Disraeli, the great British prime minister who said in 1845 that Britain had become “two nations," rich and poor, Smith said: “Since 1980, a wedge has been driven. We have become two Americas economically."

On the chronic dysfunction in Congress, Smith said: “When I came to Washington in 1962, to work for The New York Times, budgets got passed routinely. Congress passed 13 appropriations bills for different parts of the government. It happened every year."

This routine congressional action happened because there were compromises, he said, noting, “There were 70 Republicans who voted for Medicare along with 170 Democrats. (There was) compromise on the national highway system, sending a man to the moon in competition with the Russians. Compromise on a whole slew of things was absolutely common."

Smith remembered those days in Washington of order, bipartisanship and division over policy, not party. There were Southern Democrats and Northern Republicans, and Congress divided that way, but not routinely by party line.

He said, “There were Gypsy Moth Republicans who voted with Democratic presidents and Boll Weevil Democrats who voted with Republican presidents."

In fact, Smith said, there wasn't a single party-line vote on any major issue in Congress from 1945 to 1993.

“The Founding Fathers would never have imagined that we would have what the British call ‘party government.' Our system is constructed to require compromise, while we now have a political system that is gelled in bipartisanship."

On the dichotomy between the rich and the poor, Smith said that in the period from World War II up until 1980, the American middle class was experiencing a rise in its standard of living roughly keeping up with what was happening to the rich.

But since 1980, he said, “The upper 1 percent, and even the top 10 percent, have been soaring and the rest of the country has fallen off the cliff."

This dichotomy, according to Smith, has had huge political consequences.

In 2016, he said, Donald Trump ran for president as an advocate of the working class against the establishment Republicans: “He had 15 Republican (contenders) who were pro-business; they were pro-suburban Republicans who were well-educated, well-off. Trump had run on the other side, trying to grab the people who were aggrieved and left out by globalization. But we forget that," he said.

Smith went on to say that Bernie Sanders, the Democratic presidential candidate in 2016, did the same thing: “He was a 70-year-old, white-haired socialist who came from Vermont, with its three electoral votes, but he ran against the establishment candidate, Hillary Clinton ... and he damn near took the nomination away from her."

Smith said that result showed “there was rebellion against the establishment."

That rebellion, in my mind, has resulted in a worsening separation between and within the parties. They aren't making compromises which, as in times past, would offer a way forward.

A final dichotomy: The United States is the richest country the world has ever seen, and the national debt has just reached $38 trillion dollars.

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS and an international energy-sector consultant.

Horizontal game

On Oct. 12, 1914, during the third game of the 1914 World Series between the National League’s Boston Braves and the American League’s Philadelphia Athletics at Fenway Park. The Braves won the series, 4-0. They had abandoned their 43-year-old home field, The South End Grounds, in August that year, choosing to rent from the Red Sox’ Fenway while construction proceeded on Braves Field, which opened in 1915. Thus their home games in this series were also at Fenway.

The public back then loved wide-angle shots like this.

‘Sketch, Shade, Smudge’

“Woman Seated by an Easel’’ (1882-1884), by Georges Seurat, (1859-1891), in the show “Sketch, Shade, Smudge: Drawing From Gray to Black,’’ at the Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, Mass.

Chris Powell: Ex Conn. official’s trial evokes musical comedy

MANCHESTER, Conn.

At his federal trial this month was Konstantinos Diamantis, who once doubled as deputy state budget director and chief of state government's school-construction office, really trying to defend himself against bribery and extortion charges, or was he actually auditioning for a revival of the Broadway musical Fiorello?

The play humorously depicts the crusade against corruption that was waged nearly a century ago by New York City's reformist mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia. Diamantis' explanation of his work in the school-construction office would have fit right in.

According to Diamantis, he wasn't shaking down contractors for kickbacks. No, he was charging them finder's fees for introducing them to people who might be helpful to their companies. The contractors didn't see it that way. Some already had pleaded guilty to paying him the bribes he demanded, understanding the payments as the condition for getting the state construction work.

Diamantis's testimony could have been turned into another verse in “Little Tin Box,” the cleverest song from Fiorello, which consists of courtroom exchanges between a grand jury judge and corrupt city employees testifying before him.

It's surprising that Diamantis's jury needed a day and a half before deciding that his story was suitable for musical comedy and convicting him on all 21 charges. But there won't be much humor in the long prison sentence he's facing.

Lately there has been a lot of sleaze if not outright corruption in state government, the consequence of longstanding one-party rule.

Among other things, the chairwoman of the Public Utilities Regulatory Authority resigned upon being caught lying to the legislature, a court, and the public. Legislators have been caught stuffing expensive “earmarks" into the state budget to benefit nominally nonprofit organizations run by their friends. The former public college system chancellor was dismissed but is getting a year of severance worth nearly $500,000 after being caught abusing his expense account, and he is guaranteed another comfortable public college job when his severance expires.

State government is a big place and some of its denizens will always cheat and steal. While Gov. Ned Lamont is as political as any other governor, he is not corrupt; he sometimes has been badly served by those he trusted.

But it is starting to seem as if Connecticut could use its own Fiorello LaGuardia to run a perpetual grand jury investigating corruption and malfeasance in state government. Federal -- not state -- prosecutors investigated Diamantis, and the General Assembly still refuses to examine government operations, confident that there will always be plenty of money for the little tin box.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Fishing for fresh water off the New England coast

U.S. government map

Excerpted from an ecoRI.org article

“On May 19, the L/B Robert chugged out of Bridgeport, Conn., heading to an area of the Atlantic Ocean off the island of Nantucket.

“The Robert isn’t a fishing boat, or at least the kind that brings back fish, crabs or lobster.

“This expedition was fishing for water. Fresh water. Under the ocean.

“How can that be, you ask? How can fresh water be underneath the ocean floor? And how did it get there?’’

‘Discarded monument’

“Phantom Limb: My Dresser Top at Night’’ (archival pigment print), by Shellburne Thurber, in her show “Shellburne Thurber: Full Circle,’’ at the Bates College Museum of Art, Lewiston, Maine, through March 21.

The museum says the show focuses on “interior work that is private, domestic, psychological, or insular. While not explicitly ‘spooky,’ Thurber's atmospheric photographs of abandoned, derelict and, inversely, intensely lived-in spaces are still haunting in that they call upon memories of lives once lived in the scenes she captures. According to curatorial material, ‘each photograph invites us into a discarded monument for everyday lives carried out in the passage of time at these exact sites: secrets, emotions, and interactions by anonymous people or known intimately to the artist."

Chuck Collins: 10 ways in which the system lets billionaires burn us

Abigail Johnson, CEO of the Johnson family-controlled Fidelity Investments, is the richest person in New England, according to Forbes, with a net worth in 2024 of $29 billion.

The richest in the rest of New England:

Vermont: John Abele, $1.9 billion

Maine - Susan Alfond, $3.1 billion

Rhode Island - Jonathan Nelson, $3.4 billion

New Hampshire - Rick Cohen & family, $19.6 billion

Connecticut - Steve Cohen, $19.8 billion

Data from Congressional Budget Office

Text via OtherWords.org

I’ve spent my career highlighting the problems posed by extreme wealth. Not everyone buys it. “None of my problems exist as a result of someone else being a billionaire,” Greg B. recently wrote to me.

The problem isn’t individual billionaires, I told Greg. It’s the system of laws, rules, and regulations tipped in favor of the wealthy at the expense of working folks.

I wrote my new book, Burned by Billionaires, to help folks like Greg understand this system better. Here are 10 ways you — yes, you personally — are being burned by billionaires, pulled from my book.

1. They stick you with their tax bill. By dodging taxes in ways unavailable to ordinary workers, billionaires shift responsibility onto you to pay for everything from infrastructure to defense and veterans services.

2. They rob you of your voice. Your vote might still make a difference, but billionaires now dominate candidate selection, campaign finance, and policy priorities. The billionaires love gridlock and government shutdowns because they can block popular legislation.

3. They supercharge the housing crisis. Billionaire demand for luxury housing is driving up the cost of land and housing construction for everyone. Billionaire speculators are also buying up rental housing, single family homes, and mobile home parks to squeeze more money out of the housing shortage.

4. They inflame our divisions. The billionaires don’t want you to understand how they’re picking your pocket, so they pour millions into partisan media organizations and divisive politicians to deflect our attention. This divisive agenda drives down wages, worsens the historic racial wealth divide, and scapegoats immigrants.

5. They’re trashing your environment. While you’re recycling and walking, they’re zooming around in private jets and yachts with the carbon emissions of small countries.

6. They’re making you sick. Billionaire-backed private equity funds are buying up hospitals and drug companies to squeeze more out of health care consumers. Health outcomes in societies with extreme disparities in wealth are worse for everyone, even the rich, than societies with less inequality.

7. They’re blocking action on climate. Fossil fuel billionaires spend millions to block the transition to a healthy future, keep their coal plants open, and shut down competing wind projects. They’re running out the clock for our governments to take action to avert the worst impacts of climate disruption.

8. They’re coming for your pets. Billionaire private equity funds know we love our pets like family. To squeeze more money out of us, they’re buying up veterinary care, medical specialties, pet food and supply companies, and pet care services like Rover.com.

9. They’re dictating what’s on your dinner plate. The food barons — the billionaires that monopolize almost every sector of the food economy — are dictating the price, ingredients, and supply of most food.

10. They’re corrupting charity. Billionaire philanthropy has become a taxpayer-subsidized form of private power and influence. As philanthropy gets more top-heavy — with most charity dollars flowing from the ultra-wealthy — it distorts and warps the independence of nonprofits.

But there’s so much we can do to fight back.

You can talk to your neighbors about these 10 ways they’re feeling the burn and organize a discussion group. When your neighbor complains about their taxes, explain how the billionaires lobbied to shift taxes away from themselves and onto everyone else.

You can join campaigns to invest in housing, education, and clean energy by taxing the rich. If federal changes are blocked by the billionaires, work at the state and local level. Or you can join satirical resistance groups like “Trillionaires for Trump.”

Finally, you can learn more about inequality and how to fight it at Inequality.org, the website I co-edit for the Institute for Policy Studies.

Billionaires have the cash, but we have something they don’t: each other. And we’re tired of being burned.

Chuck Collins, based in Vermont, directs the Program on Inequality, and co-edits Inequality.org, for the Institute for Policy Studies.

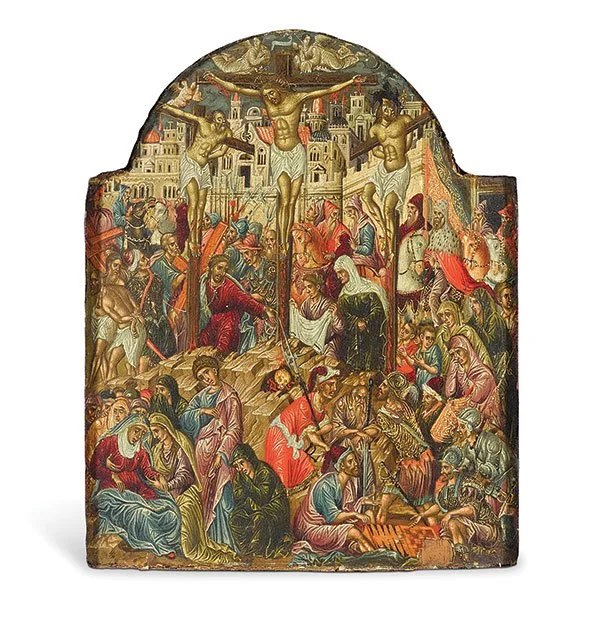

Iconic Clinton

“Crucifixion” (egg tempera on wood), attributed to Georgios Klontzas, panel from a triptych, 16th Century, in Crete, at the Icon Museum and Study Center in Clinton, Mass.

The Foster Fountain in Clinton’s Central Park. The town, once known mostly for its factories, now is just another exurban/surburban community.

Time to sail away from ‘ruffian-like fashions and disorder’

(Politically incorrect) Seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

“The fountains of learning and religion are so corrupted that most children (besides the unsupportable charge of their education) are perverted, corrupted, and utterly overthrown by the multitude of evil examples and the licentious government of those seminaries, where men strain at gnats and swallow camels, and use all severity for maintenance of caps and like accomplishments, but suffer all ruffian-like fashions and disorder in manners to pass uncontrolled.’’

— From “Reasons for the Plantation in New England,’’ written in 1628 in England by John Winthrop (1588-1649), the Puritan lawyer and key leader of the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

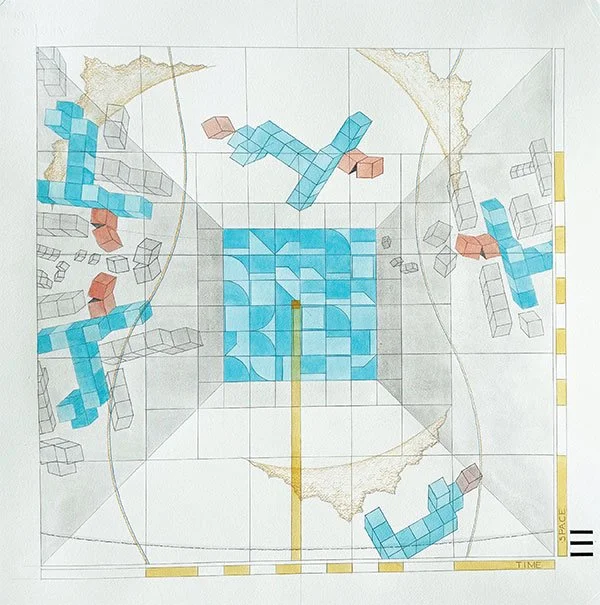

Quantum physics and art

“Chart #3,’’ by John Anderson, in the group show “Stardust,’’ at Mad River Valley Arts, Waitsfield, Vt., through Oct. 31.

The gallery says:

“The Mad 802 Collective presents “Stardust,’’ an exhibition about The Quantum World. This multimedia installation looks at the behavior of photons, particles and mysterious patterns of quantum phenomena, inspiring us to think about the magic of the quantum fundamental basis to reality. Artists open up to their interpretation of the immaterial while engaging with the scales of the unimaginably tiny to the infinitely large.’’

Oona Zena: Single people worry about dying alone

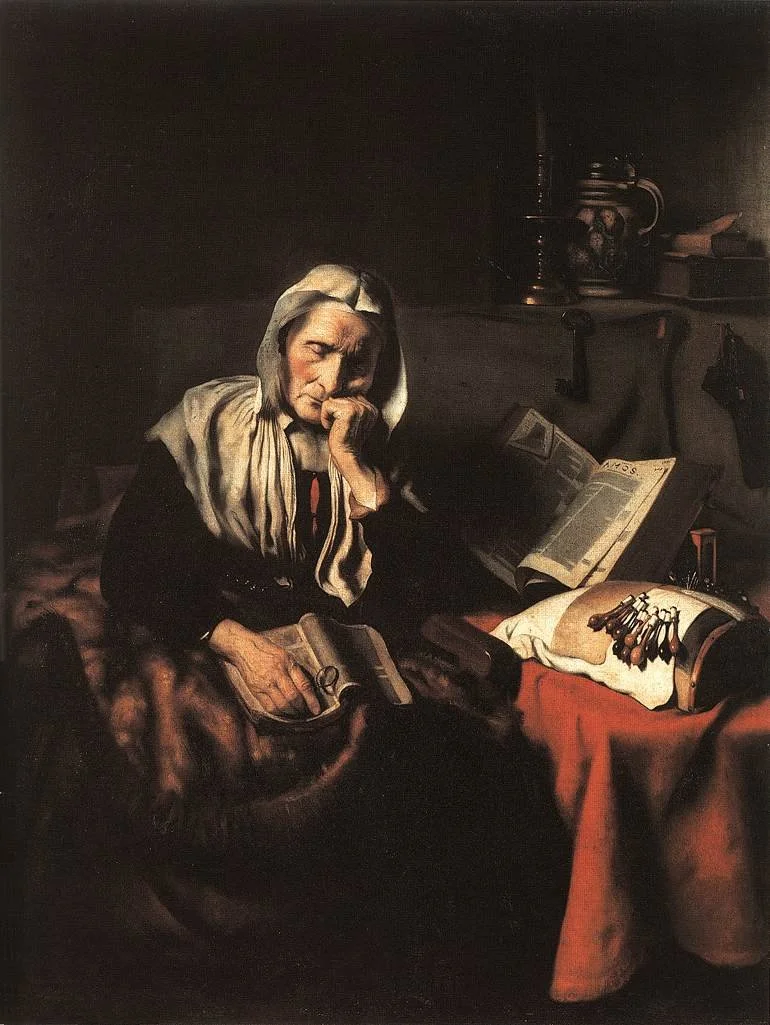

“Old Woman Dozing,’’by Nicolaes Maes (1656).

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News (except for picture above).

This summer, at dinner with her best friend, Jacki Barden raised an uncomfortable topic: the possibility that she might die alone.

“I have no children, no husband, no siblings,” Barden remembered saying. “Who’s going to hold my hand while I die?”

Barden, 75, never had children. She’s lived on her own in western Massachusetts since her husband passed away, in 2003. “You hit a point in your life when you’re not climbing up anymore, you’re climbing down,” she told me. “You start thinking about what it’s going to be like at the end.”

It’s something that many older adults who live alone — a growing population, more than 16 million strong in 2023 — wonder about. Many have family and friends they can turn to. But some have no spouse or children, have relatives who live far away, or are estranged from remaining family members. Others have lost dear friends they once depended on to advanced age and illness.

More than 15 million people 55 or older don’t have a spouse or biological children; nearly 2 million have no family members at all.

Jacki Barden has prepared thoroughly for the end of her life. Her paperwork is in order and funeral arrangements are made. But she says she’s not sure anyone will be with her when she dies.

Still other older adults have become isolated due to sickness, frailty, or disability. Between 20% and 25% of older adults, who do not live in nursing homes, aren’t in regular contact with other people.

And research shows that isolation becomes even more common as death draws near.

Who will be there for these solo agers as their lives draw to a close? How many of them will die without people they know and care for by their side?

Unfortunately, we have no idea: National surveys don’t capture information about who’s with older adults when they die. But dying alone is a growing concern as more seniors age on their own after widowhood or divorce, or remain single or childless, according to demographers, medical researchers, and physicians who care for older people.

“We’ve always seen patients who were essentially by themselves when they transition into end-of-life care,” said Jairon Johnson, the medical director of hospice and palliative care for Presbyterian Healthcare Services, the largest health-care system in New Mexico. “But they weren’t as common as they are now.”

Attention to the potentially fraught consequences of dying alone surged during the COVID-19 pandemic, when families were shut out of hospitals and nursing homes as older relatives passed away. But it’s largely fallen off the radar since then.

For many people, including health-care practitioners, the prospect provokes a feeling of abandonment. “I can’t imagine what it’s like, on top of a terminal illness, to think I’m dying and I have no one,” said Sarah Cross, an assistant professor of palliative medicine at Emory University School of Medicine, in Atlanta.

Cross’s research shows that more people die at home now than in any other setting. While hundreds of hospitals have “No One Dies Alone” programs, which match volunteers with people in their final days, similar services aren’t generally available for people at home.

Alison Butler, 65, is an end-of-life doula who lives and works in the Washington, D.C., area. She helps people and those close to them navigate the dying process. She also has lived alone for 20 years. In a lengthy conversation, Butler admitted that being alone at life’s end seems like a form of rejection.

She choked back tears as she spoke about possibly feeling her life “doesn’t and didn’t matter deeply” to anyone.

Alison Butler has lived alone for 20 years, since her divorce. “Solo agers tend to feel forgotten,” she says. “That makes the anxiety around end-of-life even worse for solo agers.”

Without reliable people around to assist terminally ill adults, there’s also an elevated risk of self-neglect and deteriorating well-being. Most seniors don’t have enough money to pay for assisted living or help at home if they lose the ability to shop, bathe, dress, or move around the house.

Nearly $1 trillion in cuts to Medicaid planned under President Trump’s tax-and-spending law, previously known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” probably will compound difficulties accessing adequate care, economists and policy experts predict. Medicare, the government’s health insurance program for seniors, generally doesn’t pay for home-based services; Medicaid is the primary source of this kind of help for people who don’t have many financial resources. But states may be forced to eviscerate Medicaid home-based care programs as federal funding diminishes.

“I’m really scared about what’s going to happen,” said Bree Johnston, a geriatrician and the director of palliative care at Skagit Regional Health, in northwestern Washington State. She predicted that more terminally ill seniors who live alone will end up dying in hospitals, rather than in their homes, because they’ll lack essential services.

“Hospitals are often not the most humane place to die,” Johnston said.

While hospice care is an alternative paid for by Medicare, it too often falls short for terminally ill older adults who are alone. (Hospice serves people whose life expectancy is six months or less.) For one thing, hospice is underused: Fewer than half of older adults under age 85 take advantage of hospice services.

Also, “many people think, wrongly, that hospice agencies are going to provide person power on the ground and help with all those functional problems that come up for people at the end of life,” said Ashwin Kotwal, an associate professor of medicine in the division of geriatrics at the University of California-San Francisco School of Medicine.

Instead, agencies usually provide only intermittent care and rely heavily on family caregivers to offer needed assistance with activities such as bathing and eating. Some hospices won’t even accept people who don’t have caregivers, Kotwal noted.

That leaves hospitals. If seniors are lucid, staffers can talk to them about their priorities and walk them through medical decisions that lie ahead, said Paul DeSandre, the chief of palliative and supportive care at Grady Health System in Atlanta.

If they’re delirious or unconscious, which is often the case, staffers normally try to identify someone who can discuss what this senior might have wanted at the end of life and possibly serve as a surrogate decision-maker. Most states have laws specifying default surrogates, usually family members, for people who haven’t named decision-makers in advance.

If all efforts fail, the hospital will go to court to petition for guardianship, and the patient will become a ward of the state, which will assume legal oversight of end-of-life decision-making.

In extreme cases, when no one comes forward, someone who has died alone may be classified as “unclaimed” and buried in a common grave. This, too, is an increasingly common occurrence, according to “The Unclaimed: Abandonment and Hope in the City of Angels,” a book about this phenomenon, published last year.

Shoshana Ungerleider, a physician, founded End Well, an organization committed to improving end-of-life experiences. She suggested that people make concerted efforts to identify seniors who live alone and are seriously ill early and provide them with expanded support. Stay in touch with them regularly through calls, video, or text messages, she said.

And don’t assume that all older adults have the same priorities for end-of-life care. They don’t.

Barden, the widow in Massachusetts, for instance, has focused on preparing in advance: All her financial and legal arrangements are in order and funeral arrangements are made.

“I’ve been very blessed in life: We have to look back on what we have to be grateful for and not dwell on the bad part,” she told me. As for imagining her life’s end, she said, “it’s going to be what it is. We have no control over any of that stuff. I guess I’d like someone with me, but I don’t know how it’s going to work out.”

Some people want to die as they’ve lived — on their own. Among them is 80-year-old Elva Roy, founder of Age-Friendly Arlington, Texas, who has lived alone for 30 years after two divorces.

When I reached out, she told me she’d thought long and hard about dying alone and is toying with the idea of medically assisted death, perhaps in Switzerland, if she becomes terminally ill. It’s one way to retain a sense of control and independence that’s sustained her as a solo ager.

“You know, I don’t want somebody by my side if I’m emaciated or frail or sickly,” Roy said. “I would not feel comforted by someone being there holding my hand or wiping my brow or watching me suffer. I’m really OK with dying by myself.”

Oona Zenda is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter (ozenda@kff.org)

John O. Harney: Immigration and geometry intersect on the Greenway in Boston

Art installation near Dewey Plaza, in downtown Boston, by Brooklyn-based artist Victor “Marka27” Quiñonez, featuring coolers spray-painted gold and images reminiscent of Mexican folk-art altars.

Early this fall, I took up an offer from the folks at the Armenian Heritage Park to present a lesson connecting immigration and geometry in the context of the Rose Kennedy Greenway, in Boston.

The lesson is part of a grant-funded curriculum developed by the Friends of the Armenian Heritage Park in collaboration with the 4th grade teachers at Boston’s Eliot K-8 Innovation School. The curriculum has been implemented in more than a dozen other public schools in Boston and beyond with funding for bus transportation from the schools to the Greenway.

The intent of the curriculum called “Geometry as Public Art: Telling A Story” is to spark awareness of geometric shapes and their expression of ideas and thoughts, and to engage students in sharing their own or their families’ immigrant experience and, in doing so, celebrate what unites and connects us.

It’s all very warm and loving despite the masked ICE agents operating a few hundred years away—and the general anxiety and avoidance of the topic a few miles beyond.

The event organizers provided a script for me to memorize. I was tempted to mention that even in my pre-retirement professional days, I always resisted speaking from a script and, in those days, urged others to resist, too. But also appreciating a crutch, I went along.

Another challenge: I hated geometry in school. Sure, I had done OK in math grade-wise and later published work in The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE) on the importance of school math if only to help ensure that students pursue education beyond high school as an entry to good jobs.

But I couldn’t call it a special strength.

The twain shall meet?

I left the NEJHE editorship in early 2023 and began volunteering in phenology at the Greenway, in Boston, and in English language teaching at the Immigrant Learning Center (ILC) in Malden, Mass.

I have posted occasional reflections on the Greenway gig in my blog. I’ve posted less about the ILC experience. I’ve worried about drawing attention to the immigrant students who are made vulnerable by America’s xenophobia and advancing nationalism. Here though was a rare chance to see these two interests meet.

I have occasionally suggested that groups from the ILC tour the Greenway. Understandably, the newcomers thought that my Greenway garden work had to do with growing crops for food, not the more First-World idea of gardening for aesthetics associated with the Greenway.

Beyond the Armenian Heritage Park, the larger Greenway features notable recognition of the importance of immigration. Theoretically, other parcels along the Greenway were intended to celebrate the immigration flavors of their neighborhoods, as the Chinatown parcel does well with its bamboo planting, waterfall and recirculating stream.

Most recently, an art installation near Dewey Plaza by Brooklyn-based artist Victor “Marka27” Quiñonez, featuring coolers spray-painted gold and images reminiscent of Mexican folk art altars, paying tribute to the various groups of immigrant that have journeyed to Boston.

The Armenian geometry engagement also gave me an excuse for a mid-October visit to the Greenway for my routine bloom monitoring. It’s a time when few flowers are blooming, but there is that beauty unique to New England fall (if you’re OK with the approaching cold).

Amid the wilting astilbes, browning goldenrods and now hit-and-miss hydrangeas, a few colorful attractions remain. Among them: fall crocuses flowering pale bluish, vivid pink anemones, pink turtleheads, fluffy white snakeroot, nasturtium, isolated amaranths, resilient Russian Sage, purplish asters and red-fruiting winterberries.

The curriculum

The multidisciplinary curriculum in the Armenian Heritage Park integrates geometry, art, language and social studies while promoting cross-cultural understanding and respect.

The way it works: In Lesson One in the classroom, students discover geometric shapes, view info about the park and receive an “About My Family” questionnaire to guide a conversation with a family member or friend to learn about the first person in their family to come to the U.S.

Lesson Two (the one I was involved with) takes place at the park, where students experience firsthand how the park’s geometric features tell the story of the immigrant experience. They view an abstract sculpture, a split rhomboid dodecahedron, which is reconfigured every year to symbolize the story of the immigrant experience, “one that unites and connects us.” (The 2025 reconfiguration was scheduled for Oct. 19.)

The split rhomboid dodecahedron sits on a reflecting pool. An inscription notes: “The sculpture is dedicated to lives lost during the Armenian Genocide of 1915-1923 and all genocides that have followed.”

The water of the reflecting pool washes over the sides and re-emerges as a single jet of water at the center of the labyrinth (at least until the city turns off the water in mid-October as colder weather sets in).

The labyrinth celebrates life’s journey. The labyrinth serves as a place for meditative practice to reduce stress (though 4th-graders liberated by a field-trip day naturally relieve their stress by jumping and horsing around). There is one path leading to the center of the labyrinth and the same path leading out, symbolic of a new beginning, but clearly connected to where it began. The jet of water at its center represents rebirth.

The few calm students read the inscription on a reflecting pool on which the sculpture sits.

Ideally, the students discover the words etched around the: art, science, service, commerce in recognition of the contributions made to life and culture.

Students then write a wish on a ribbon for “The Wishing Tree.”

Back in the classroom for Lesson Three, students reflect on their visit to the park and receive the “I AM” poem template to create their poem, using an About My Family questionnaire. The poem is written in the voice of the first person in their family (sometimes the student) to come to this country. Students also create a portrait of that person or a geometric illustration.

Some messages on the Wishing Tree show hope, some signal worries. One youngster tackling his packed lunch, tells a friend, “things will be bad for four years because of Trump.” And indeed, these school kids, like so many across America, have the complexions that make them targets today.

For our spooky season

“Apple Tree at Night” (archival pigment print), by Jocelyn Lee, in the show “The Haunted: Contemporary Photography Conjured in New England,’’ at Moss Gallery, Falmouth, Maine, through Nov. 29.

1910 postcard