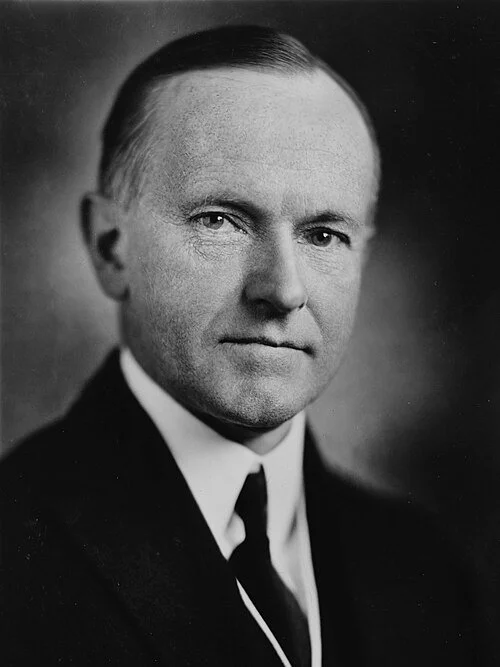

Selling solemnity

President Calvin Coolidge in 1924. He was born in Vermont and became a Massachusetts lawyer and politician, including the governorship.

“I always figured the American public wanted a solemn ass for President, so I went along with them.’’

— Calvin (“Silent Cal”) Coolidge (1872-1933), president (1923-1929)

‘My world’

“North Haven VI’’ (oil on canvas), by Midcoast Maine painter Eric Hopkins, at Portland (Maine) Art Gallery.

He says:

"Seeing the Earth from the sky, from a plane — the boats in the water, the islands {like North Haven} — it was just my life, my world, and I was fascinated by it.”

A culinary abomination

Poseur

The real stuff

“There is a terrible pink mixture (with tomatoes in it and herbs) called Manhattan Clam Chowder, that is only a vegetable soup, and not to be confused with New England Clam Chowder, nor spoken of in the same breath. Tomatoes and clams have no more affinity than ice cream and horseradish".

-From Eleanor Early, in her 1940 book, A New England Sampler

50 years after the war, looking at Vietnamese artists shown in Greenwich

“Fish and the Forest” (oil on canvas), by Dinh Thi Tham Poong, in the show “Vietnam: Tradition Upended,” at Flinn Gallery at Greenwich (Conn.) Library, Sept. 18-Nov. 12.

— Photo Credit: Art Vietnam Gallery

The curators explain:

“In collaboration with Art Vietnam Gallery in Hanoi, this exhibition features nine interdisciplinary artists who work in a variety of mediums and styles. These artists all take time-honored traditions and materials and rework them in a modern context, acknowledging the past while simultaneously breaking away. With 2025 marking exactly half a century since the end of the Vietnam War, and 30 years since the normalization of relations between Vietnam and the U.S., this is an opportune time to acquaint ourselves with the art and culture of a country that has undergone extraordinary change; a country with one of the most interesting and vibrant art scenes in Southeast Asia.’’

Paula Span: When I go, I’ll go biodegradable

Green burial site

(Except for images above, from Kaiser Family Foundation Health News)

Our annual family vacation on Cape Cod included all the familiar summer pleasures: climbing dunes, walking beaches, spotting seals, eating oysters and reading books we had intended to get to all year.

And a little shopping. My grandkid wanted a few small toys. My daughter stocked up on thousand-piece jigsaw puzzles at the game store in Provincetown. I bought a pair of earrings and a couple of paperbacks.

And a gravesite.

It’s near a cluster of oaks, in a cemetery in Wellfleet, on the Cape, where some mossy Civil War-era headstones are so weathered that you can no longer decipher who lies beneath them. The town permits nonresidents to join the locals there, and it welcomes green burials.

Regular summer visitors such as us often share the fantasy of acquiring real estate on the Cape. Admittedly, most probably envision a place to use while they’re still alive, a daydream that remains beyond my means.

Buying a cemetery plot where I can have a green burial, on the other hand, proved to be surprisingly affordable and will allow my body, once no longer in use, to decompose as quickly and as naturally as possible, with minimal environmental damage. Bonus: If my descendants ever care to visit, my grave will be in a beloved place, where my daughter has come nearly every summer of her life.

“Do you see a lot of interest in green burials?” I asked the friendly town cemetery commissioner who was showing me around.

“I don’t think we’ve had a traditional burial in two years,” he said. “It’s all green.”

Nobody can count how many Americans now choose green or natural burials, but Lee Webster, former president of the Green Burial Council, is tracking the growing number of cemeteries in the United States that allow them.

The first, Ramsey Creek Preserve, began its operations in Westminster, S.C., in 1998. By 2016, Webster’s list included 150 cemeteries; now she counts 497. Most, like the one in Wellfleet, are hybrids accommodating both conventional and green burials.

Although a consumer survey conducted by the National Funeral Directors Association found that fewer than 10% of respondents would prefer a green burial (compared with 43% favoring cremation and 24% opting for conventional burial), more than 60% said they would be interested in exploring green and natural alternatives.

“That has to do with the Baby Boomers coming of age and wanting to practice what they’ve preached,” Webster said. “They’re looking for environmental consistency. They’re looking for authenticity and simplicity.”

She added, “If you nursed your babies and you recycle the cardboard in the toilet paper roll, this is going to appeal to you.” (I raise my hand.)

Aside from their environmental concerns, many survey participants attributed their interest in green burial to its lower cost. The median price of a funeral with burial in 2023 was about $10,000, including a vault but not including the cemetery plot or a monument, according to the NFDA.

Although advocates of green burials, such as Webster, decry cremation’s toxic emissions and reliance on fossil fuels, the method now accounts for nearly two-thirds of body disposals in the United States, the association reports. One reason is its median cost of $6,300, without interment or a monument.

Such numbers vary considerably by location. I live in Brooklyn, where real estate is pricey even for the dead, and where Green-Wood Cemetery — a jewel and a National Historic Landmark — charges $21,000 to $30,000 for a plot. Burial in its new, green section is a comparative bargain at $15,000.

About 40 miles outside Nashville, Tenn., though, a green burial at Larkspur Conservation costs $4,000, including the gravesite and just about everything else, except, if the family wants one, a flat, engraved native stone.

Larkspur is one of 15 conservation burial grounds in the nation operating in partnership with land trusts — The Nature Conservancy, in this case — to preserve the space. “It’s what keeps forests from becoming subdivisions,” said John Christian Phifer, Larkspur’s founder.

He listed the common elements of green burials: “No chemical embalming, no steel casket, no concrete vault. Everything that goes in the ground is compostable or biodegradable.” A small industry has evolved to produce artisanal woven caskets, linen shrouds, and other eco-friendly funerary items.

Green funerals often feel different, too. Mourners at Larkspur tend to walk the trail to the burial site wearing denim and hiking boots, not black suits.

“Instead of observing, they’re actively participating,” Phifer said. “We invite them to help lower the body into the grave with ropes, to put a handful or shovelfuls of soil into the grave,” and to mound soil, pine boughs, and flowers atop it afterward. Then, they might toast the departed with champagne or share a potluck picnic.

When Larkspur began operating in 2018, with Phifer as its only employee, 17 bodies were buried on its 161 acres. Last year, a staff of eight handled 80 burials, and the burial ground is acquiring more property.

Other alternatives to conventional burial have emerged, too. The company Earth Funeral has facilities in Nevada, Washington state, and, soon, Maryland, for so-called human composting. In this process, a body is heated with plant material for 30 to 45 days in a high-tech drum, where it all eventually turns into a cubic yard of soil.

That’s 300 pounds, more than most families can use, so local land conservancies receive the rest. The cost: $5,000 to $6,000.

Alkaline hydrolysis, which is legal in almost half of all states, dissolves bodies using chemicals and water, leaving pulverized bone fragments that can be scattered or buried and an effluent that must be disposed of.

Environmentally, when you include standard cremation, “there are ramifications for all three processes that we can avoid by simply putting a body in the soil” and letting microbes and fungi do the rest, Webster said.

Cemetery acreage near major population centers is limited, however, and increasingly expensive. “I don’t think there’s a perfect option, but we can do a hell of a lot better than the traditional methods,” said Tom Harries, founder of Earth Funeral. Debates about comparative greenness will certainly continue.

But green burial made sense to Lynne McFarland and her husband, Newell Anderson, who heard about Larkspur through their Episcopal church in Nashville. “The idea of returning to the earth sounded good to me,” McFarland said.

Her mother, Ruby Fielden, who was 94 when she died, was one of the first people buried at Larkspur in 2018, in an open meadow that attracts butterflies.

Last spring, Anderson, who had Alzheimer’s, died at 90 and was buried a few yards away from Fielden, in a biodegradable willow casket. A dozen family members read prayers and poems, shared stories and sang “Amazing Grace.”

Then they picked up shovels and filled the grave. It was exactly what her outdoorsy husband, a onetime Boy Scout leader, would have wanted, said McFarland, 80, who plans to be buried there, too.

I’m not sure if my survivors will undertake that much physical labor. But my daughter and son-in-law, though probably decades from their own end-of-life decisions, liked the idea of green burial in a place we all cherish.

The prices in what I now think of as my cemetery were low enough — $4,235, to be precise — that I could buy a plot to accommodate myself and seven descendants, if I ever have that many.

I hope this plan, besides minimizing the impact of my death on a fragile landscape, also lessens the familial burden of making hurried arrangements. At 76, I don’t know how my future will unfold. But I know where it will conclude.

Paula Span is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter.

‘Off balance there’

Gibbous moon

“Unheralded, the gibbous moon

arrives too late, if not too soon,

a goblet neither full nor empty,

off balance there, like Humpty Dumpty….’’

— From “Gibbous Moon,’’ by Alfred Nicol, Massachusetts-based poet

As time speeds up

“Marking Time” (intaglio, relief collage, drawing on player piano scroll), by Randy Garber, in the show “So Late So Soon’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Sept. 28.

The gallery explains:

“‘So Late So Soon’ is a collaboration and dialogue between mother and daughter artists Randy Garber and Rachel Garber Cole. The work explores the concept of time: how it speeds up and lengthens, how the climate crisis catapults us simultaneously into the future and into our geological past. As humanity sits at the edge of our own geological era (the Holocene), and as our planet warms rapidly to a world unrecognizable to 10,000 years of human consciousness, the artists ask: How do we weave the passage of time (and timescale) into the fabric of our daily lives? How do we attend to the micro when the macro is shifting around us in unexpected ways?’’

Don Morrison: My strange long-ago encounter with conspiracy theorist RFK Jr.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. earlier this year.

Back in 1982, I got invited to a reception at Hickory Hill, the Kennedy family spread in Virginia just outside Washington, D.C. The event had something to do with the opening of the Vietnam War Memorial, and I was there as a journalist.

I was thrilled at the opportunity to meet the grande dame of the estate, Robert F. Kennedy’s indomitable widow, Ethel (clever and charming), as well as a passel of current and future public officials (many of them Kennedys).

My most vivid memory of the event is getting cornered by Robert Kennedy Jr., who was fresh out of law school and eager to save the world — in particular, through legalizing psychedelic drugs for treating mental illness, a far-fetched idea in those war-on-drugs days.

I didn’t know about his own substance abuse back then {he was a long-time heroin addict}, or else I might have suspected an underlying influence. In any case, he hinted darkly that big drug companies were undermining his crusade. The more that he talked — and, boy, did he talk — the less sense he made.

I think of that conversation whenever I read about RFK Jr.’s rocky tenure as our 26th secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Why Donald Trump chose a longtime crusader against vaccines and other proven tools of public health, we’ll never know — though there is a strong anti-science strain among the MAGA crowd.

Kennedy has wasted little time dismantling the nation’s public-health system. He has cut medical-research budgets, fired qualified administrators and scientists; replaced them with inexperienced amateurs and fellow anti-vaccine activists; and made it harder to get the shots that protect children from such lethal threats as measles and polio — and all of us from COVID. Why, I wonder, is he trying to kill us?

I have a theory, based largely on RFK Jr.’s history and slightly on my encounter with him: He exhibits all the symptoms of a chronic conspiracy theorist.

For decades, Kennedy has been pushing far-fetched notions about election interference, unproven links between wireless technology and cancer, as well as between childhood vaccines and autism. He has touted the alleged benefits of raw (i.e., unpasteurized and thus highly risky) milk and the COVID-fighting properties of the horse deworming drug Ivermectin. He has warned darkly about the power of big pharmaceutical firms to block low-cost cures for illness.

The best conspiracy theories contain just enough truth to be intriguing. (RFK Jr.’s suspicions about “Big Pharma” seem at least modestly plausible).

But even the worst ones are emotionally satisfying, especially to people who are insecure, hungry for meaning in a confusing world or recovering from some unexplainable trauma.

RFK Jr.’s trauma was losing his father at 14 to an assassin’s bullet, five years after losing his uncle John the same way. Even for people who merely read about such puzzling tragedies, alternative theories are compelling. Indeed, RFK Jr. subscribes to the unproven notion that two gunmen, not one, took part in his father’s killing, which would suggest a larger conspiracy.

Moreover, some people get an ego boost by thinking that they possess inside knowledge others don’t. Finding fellow believers is especially pleasing, a phenomenon that explains the popularity of online conspiracy echo-chambers.

Psychologists say that humans are hard-wired for conspiracy thinking. We’re subject to what is known as confirmation bias: overvaluing facts that confirm our prior suspicions. Then there is “intentionality bias,” believing that things happen on purpose rather than by chance; and “proportionality bias,” the notion that big events must have big causes.

Besides, conspiracy theories are often more interesting than mundane reality. They have stronger storylines, more coherent plots and compelling villains. “The moon landing was faked” makes for a better movie than “the moon landing went fine.” And if your life, like mine, happens to be on the quiet side, it’s hard to resist a good story.

Hmmm. I’m beginning to wonder whether my attempt to paint RFK Jr. as a conspiracy nutcase doesn’t itself exhibit some of the above-mentioned symptoms. Maybe I’m a closet conspiracy theorist. After all, my narrative does make for a better story than “RFK is a just a normal, boring bureaucrat.”

Interestingly, his crusade to legalize psychedelic drugs for treatment of mental illness has been bolstered lately by some positive research results. Medical experts are starting to take the idea seriously.

Indeed, what if we mainstream critics have got it all wrong? What if RFK Jr. is not just correct in his beliefs but also the mastermind of a secret Trump-backed operation to discredit the naysayers by luring us into ludicrous excesses of denial — a plot the current HHS secretary might have hatched back at Hickory Hill decades ago after a chat with some obnoxious journalist?

And what if, any day now, he and his boss in the White House pull the rug out from under us doubters with some documented, irrefutable, headline-grabbing disclosures: “Big Pharma caught suppressing cheap drugs!” “Horse dewormer really does prevent COVID!” “Raw milk cures cancer!”

This movie would no doubt end with me bound and gagged in a dank basement room at Hickory Hill. RFK Jr. approaches with a gleam in his eye and, in his hand, a large syringe full of Ivermectin. Now there’s a plot for you. Call my agent!

Don Morrison, partly based in western Massachusetts’s Berkshire Hills, is an author, editor and university lecturer. A longtime former editor at Time Magazine in New York, London and Hong Kong, he has written for such publications as The New York Times, the Financial Times, Smithsonian, Le Monde, Le Point and Caixin. He is currently a columnist and advisory board co-chair at The Berkshire Eagle, a podcast commentator for NPR’s Robin Hood Radio and Europe editor for Port Magazine.

As long as they stay up there

“Leaf Children” (oil on canvas), by Pavel Tchelitchew (1898-1957), in the show “Green Mountain Magic: Uncanny Realism in Vermont,’’ at the Bennington Museum, through Nov. 2.

Dan Howells/Todd Larsen: The hefty price of ‘free’ AI tools

A rendering of a proposed artificial intelligence data center in Westfield, Mass., according to Servistar Realties’ application from 2021. The $4 billion “hyperscale" data center campus is planned near the Westfield-Barnes Regional Airport, in western Massachusetts. A new state law provides sales- and use-tax exemptions to lure more data centers.

Via OtherWords.org

Artificial intelligence is everywhere. But its powerful computing comes with a big cost to our planet, our neighborhoods, and our wallets.

AI servers are so power-hungry that utilities are keeping coal-fired power plants that were slated for closure running to meet the needs of massive servers.

And in the South alone, there are plans for 20 gigawatts of new natural-gas power plants over the next 15 years — enough to power millions of homes — just to feed AI’s energy needs.

Such multibillion-dollar companies as Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta that previously committed to 100 percent renewable energy are going back to the Jurassic Age, using such fossil fuels as coal and natural gas to meet their insatiable energy needs. Even nuclear- power plants are being reactivated to meet the needs of power-hungry servers.

At a time when we need all corporations to reduce their climate footprint, carbon emissions from major tech companies in 2023 have skyrocketed to 150 percent of average 2020 values.

AI data centers also produce massive noise pollution and use huge amounts of water. Residents near data centers report that the sound keeps them awake at night and their taps are running dry.

Many of us live in communities that either have or will have a data center, and we’re already feeling the effects. Many of these plants further burden communities already struggling with a lack of economic investment, access to basic resources, and exposure to high levels of pollution.

To add insult to injury, amid stagnant wages and increasing costs for food, housing, utilities, and consumer goods, AI’s demand for power is also raising electric rates for customers nationwide. To meet the soaring demand for energy that AI data servers demand, utilities need to build new infrastructure, the cost of which is being passed onto all customers.

A recent Carnegie Mellon study found that AI data centers could increase electric rates by 25 percent in Northern Virginia by 2030. And NPR recently reported that AI data centers were a key driver in electric rates increasing twice as fast as the cost of living nationwide — at a time when one in six households are struggling to pay their energy bills.

All of these impacts are only projected to grow. AI already consumes enough electricity to power 7 million American homes. By 2028, that could jump to the amount of power needed for 22 percent of all US households.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

AI could be powered by renewable energy that is non-polluting and works to reduce energy costs for us all. The leading AI companies, who have made significant climate pledges, must lead the way.

Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Meta have all made promises to the communities they serve to tackle climate and pollution. They all have climate pledges. And they have made significant investments in renewable energy in the past.

Those investments make sense, since renewables are the most affordable form of electricity. These companies have the know-how and the wealth to power AI with wind, solar, and batteries, which makes it all the more puzzling that they’re relying on fossil fuels to power the future.

If these corporate giants are to be good neighbors, they first need to be open and honest about the scope and scale of the problem and the solutions needed.

As these companies invest billions in technology for AI, they must re-up investments in renewables to power our future and protect our communities. They must ensure that communities have a real voice in how and where AI data centers are built — and that our communities aren’t sacrificed in the name of profits.

Dan Howells is the Climate Campaigns director at Green America. Todd Larsen is Green America’s executive co-director.

Boston car thieves’ favorite

2023 Honda Accord LX

Boston Guardian article by Mariah Alanskas

(Full disclosure: Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s publisher and editor, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

BOSTON

Honda Accords continue to be Boston car thieves’ favorite vehicle, while many of the rest of the nation’s auto criminals target the Hyundai Elantra.

In Massachusetts, the two vehicles tied for the most stolen vehicles across the state, with 241 each being stolen in 2024, according to the National Insurance Crime Bureau (NICB).

The remaining top five spots consisted of other Honda models and Toyotas, following national trends.

In previous years, full size pickup trucks topped the list of most stolen vehicles, but it seems that car thieves in Boston and across America now favor sedan models that have inadequate anti-theft and security features. In any event, Boston’s auto thefts have been decreasing compared to last year.

According to data from the Boston Police Department’s (BPD) daily journals, there have been roughly 420 reported auto thefts since the start of the year. In comparison, around 600 thefts were reported as of September 2024.

The data suggest a continued decline in auto thefts across the city since 2023. Over 2024, a reported 1,141 vehicles were stolen, 17% down from 1,381 in 2023.

It’s the first time that the city has seen a decline since 2019.

These trends are seen in national data.

The NICB shows that 850,708 vehicles were stolen nationwide last year, down from 1,020,729 in 2023, marking the largest decrease in auto thefts in 40 years. They suggest the reason for the sudden decline could be attributed to automakers implementing new anti-theft softwares and strategies such as “turn-to-key-to-start” ignitions.

While it remains unclear whether Boston car thieves are going to continue to shrug off national car thieving preferences by preferring Hondas to Hyundais and Kias, it is clear that Boston continues to hold its place as one of the big U.S. cities safest from auto theft. The most unsafe cities so far this year include Washington, D.C., where 3,056 vehicles have been stolen so far this year. In 2024, D.C. had the highest vehicle theft rate per capita.

Massachusetts also continues to hold its ranking as the fourth-safest state from auto thefts with Maine securing the top spot, and New Hampshire and Vermont following in second and third place.

In any event, BPD suggests preventive measures should still be taken to ensure belongings and vehicles are safe. Owners should keep their vehicles locked, remove valuables and install such anti-theft devices as steering-wheel locks and car alarms to deter thieves.

‘A quiet tension’

“FOGGY PEA” (combined media on linen), by Renée Khatami, in her show “Somewhat High Key,’’ at Prince Street Gallery, New York City, through Sept. 27.

The gallery says of this show:

“The artwork is composed of textured translucent layers that shift through space emanating a quiet tension. These pieces are created with paint, media, cut marks, and pencil on paper, wood, and canvas – evoking a subtly rendered atmosphere. The title refers to the muted palette – continuing the theme from her two previous solo shows at Prince Street Gallery, ‘Under Color’ and ‘Behind the Pale’.

xxx

Mary Sargent, in “Two Coats of Paint”, said of Ms. Khatami:

“Her work perhaps conjures cross sections of geological strata, in which fragments of different shapes and colors float together until the aggregate hardens and settles into a lively new pattern. Ultimately, focusing on Khatami’s glimmering multilayered surfaces, the viewer begins to rise above the challenges of everyday life.”

xxx

For many years Ms. Khatami worked as an art director/book designer, specializing in artist’s monographs, and has authored/designed two multisensory color books for children.

Time to grow a beard?

“A Moment of Reflection” (soft pastel on sanded board), by Jodie Kain, at The Guild of Boston Artists’ “Regional Juried Exhibition,’’ through Sept. 27

Chris Powell: Yale has gotten too big for its New Haven property-tax break

Yale’s Old Campus at dusk in April 2013.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

If any news report in Connecticut this year should prompt an urgent response from state government, it's the one published last week by the Hearst Connecticut newspapers about the burden of Yale University's property-tax exemption in New Haven.

It's actually an old story but one that has never gotten proper attention from Connecticut governors and state legislators.

The essence of it is that most real estate in New Haven, being owned by nominally nonprofit entities, is exempt from municipal property taxes; that most of this exempt property is owned by Yale; and that the university, while being New Haven's largest employer and the city's main reason for being, is less of a boon than generally thought.

According to the Hearst report, the university's taxable property in New Haven, property used mainly for commercial purposes, has total value of $173 million while its tax-exempt property, used mainly for educational purposes, is valued at around $4.4 billion.

Yale pays the city $5 million annually in taxes on its taxable properties and another $22 million or so in voluntary payments for its exempt properties, or about $27 million. But without its property-tax exemption Yale would owe New Haven as much as $146 million more than the university pays now.

Of course there's no denying Yale's enormous economic contribution to New Haven and its suburbs. Without Yale, New Haven would be Bridgeport, whose reason for being, as long assumed by state government, is mainly to confine Fairfield County's poverty.

But Yale's relationship with New Haven has gotten far beyond disproportionate. As a political force the university is bigger than the city and, it seems, since state government has not acted against that disproportion, bigger than the whole state.

It's not that Yale can't afford to pay more; it has an endowment of around $40 billion, which even President Trump and the Republican majority in Congress have found the courage to begin taxing.

Nine years ago the General Assembly considered legislation to limit the university's tax exemption but did not act.

Yale has claimed that the charter that it received from Connecticut's colonial legislature in the 1700s gives the university permanent exemption from property taxes.

But the charter and its revisions under state law during the next two centuries put limits on Yale's tax exemption, the first limit being a mere 500 pounds sterling. The tax exemption was thought justified in large part because, in its early years, Yale was heavily subsidized by cash from state government and was a de-facto government institution. A remnant of this connection to state government is the continuing “ex-officio" membership of Connecticut's governor and lieutenant governor on the university's Board of Trustees.

Yale no longer gets a direct annual cash stipend from state government but its $173 million tax break is worth a lot more. That money is paid not just by New Haven's residents through their property taxes and rents but by all state taxpayers as well, since New Haven city government is so heavily subsidized by state government.

Even if the courts concluded that the university's charter, as amended over the years, puts it beyond all property taxes on educational buildings, state government could coerce Yale by restricting the acreage it owns in the city, thereby forcing it to sell property and rent it back.

Would Yale leave Connecticut if, as was proposed nine years ago, state law limited university property-tax exemptions to $2 billion per year, thereby raising Yale's annual tax bill by $70 million or so? Yale's huge endowment implies otherwise.

At least the new federal tax on large university endowments has not prompted the richest schools to start planning to leave the country.

The additional property-tax revenue paid by Yale could be divided equally between New Haven and state government, state government recovering its share by reducing its financial aid to the city.

Of course those governments probably wouldn't spend the windfall very well, but it's the principle of the thing.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Maybe from a dream while napping

“In Translation 3” (woven cotton paper, ink, acrylic and colored pencil mounted on panel), by Hetty Baiz, in the group show “Paper Work,’’ at the Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine, Sept. 13-Oct. 11.

Her Web site says her images:

“Appear to be fading into the surface, or perhaps emerging from it, and the identity of the subject is absorbed into the materiality. Open ended questions about transience and the nature of being – of identity, mortality, and time, are intrinsic to her work.’’

‘You can’t eat granite’

Granite quarry in Barre, Vt.

“They can have their granite. I’ll take the good clean earth for me…. People can get along without tombstones, but they can’t get along without food, they can’t get along without potatoes, eggs, milk, butter, bread, vegetables. You can’t eat granite.”

— Vermont farmer quoted in Men Against Granite, a selection of 55 interviews by Mari Tomasi conducted in 1938-1940 by the Federal Writers Project in Vermont.

Llewellyn King: Amidst immigration crisis, from special relationship to odd couple

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Through two world wars, it has been the special relationship: the linkage between the United States and Britain. A linkage forged in a common language, a common culture, a common history, and a common aspiration to peace and prosperity.

The relationship, always strong, was especially burnished by the friendship of President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Now it looks as though the special relationship has morphed into the odd couple.

Britain, it can be argued, went off the rails in 2016 when, by a narrow majority, it voted to pull out of the European Union.

With a negative growth rate, and few prospects of an economic spurt, Britons can now ponder the high price of chauvinism and the vague comfort of untrammeled sovereignty. Americans could ponder that, too, in the decades ahead.

Will tariffs -- which have already driven China, Russia and India into a kind of who-needs-America bloc -- be the United States’ equivalent of Brexit? An economic idea which doesn’t work but has emotional appeal. An idea that is isolating, confining and antagonizing.

A common thread in the national dialogues is immigration.

Britain is swamped. It is dealing with an invasion of migrants that has changed and continues to change the country.

In 2023, according to the U.K.’s Office for National Statistics, 1.326 million migrants moved to Britain; last year, the number was 948,000. There has been a steady flow of migrants over the past 50 years, but it has increased dramatically due to wars around the globe.

Among European countries, Britain, to its cost, has had the best record for assimilating new arrivals. It is a migrant heaven, but that is changing with immigrants being blamed for a rash of domestic problems, from housing shortages to vastly increased crime.

In the 1960s, Britain had very little violent crime and street crime was slight. Now crime of all kinds -- especially using knives -- is rampant, and British cities rival those across America -- although crime seems to be declining in America, while it is rising in Britain.

Britain has a would-be Donald Trump: Nigel Farage, leader of the Reform UK party, which is immigrant-hostile and seeks to return Britain to the country it was before migrants started crossing the English Channel, often in small boats.

Farage has been feted by conservatives in Congress, where he has been railing against the draconian British hate-speech laws, which he sees as woke in overdrive.

Britain has been averaging 30 arrests a day for hate speech and related hate crimes, few of which result in convictions.

Two recent events highlight the severity of these laws. Lucy Connolly, the 42-year-old wife of a conservative local politician, took issue with the practice of housing immigrants in hotels; she said the hotels should be burned down. Connolly was sentenced to 31 months in jail. She has been released, after serving 40 percent of her sentence.

A very successful Irish comedy writer for British television, Graham Linehan, posted attacks on transgender women on X. On Sept. 1, after a flight from Arizona, he was met by five-armed policemen and arrested at London’s Heathrow Airport.

Britain’s hate laws, which are among the most severe in the world, run counter to a long tradition of free speech, dating back to the Magna Carta, in 1215. An attempt to get more social justice has resulted in less justice and abridged the right to speak out. A crisis in a country without a formal constitution.

On Sept. 17, President Trump is due to begin a state visit to Britain. Fireworks are expected. Trump’s British supporters, despite Farage and his hard-right party, are still few and public antipathy is strong.

Trump, for his part, will seek to make his visit a kind of triumphal event, gilded with overnight posts on Truth Social on how Britain should emulate him.

The British press will be ready with vituperative rebukes; hate speech be damned.

It is unlikely that the Labor government, whose membership is as diverse and divided as that of the Democratic Party, will find anything to call hate speech about attacks on Trump. A good dust-up will be enjoyed by all.

Isolated, the odd couple have each other.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

‘Memory and sensation’

“double spiral (blooms)’’ (oil on canvas), by Beverly Acha, in the group show “Making Space,’’ at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum & Art Center, through Nov. 2.

The museum says:

“Beverly Acha’s pastels and oil on canvas use an abstract visual language that she initially developed through observing her day-to-day surroundings, referencing architectural structures, scientific diagrams, the botanical world, and landscape. Acha’s works express memory and sensation as richly hued forms that vibrate with energy, creating a charged atmosphere with deceptively simple means. She asks us to examine our own awareness of the spaces around us and how we make sense of time, memory, and movement.’’

New England Youth Theatre, in Brattleboro.

Before Trump went after it

Harvard Square in 2015

“I just remember getting really drunk {in Harvard Square} and spending a lot of time trying to pick up a waitress. She went to Harvard. I was really impressed….Because, if you’re over at B.U., or if you’re at any school in this area that isn’t Harvard, you have an inferiority complex which I developed to a full-on resentment.’’

— Marc Maron (born 1963), stand-up comedian and podcaster

Map of Harvard Square in 1873