Time to grow a beard?

“A Moment of Reflection” (soft pastel on sanded board), by Jodie Kain, at The Guild of Boston Artists’ “Regional Juried Exhibition,’’ through Sept. 27

Chris Powell: Yale has gotten too big for its New Haven property-tax break

Yale’s Old Campus at dusk in April 2013.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

If any news report in Connecticut this year should prompt an urgent response from state government, it's the one published last week by the Hearst Connecticut newspapers about the burden of Yale University's property-tax exemption in New Haven.

It's actually an old story but one that has never gotten proper attention from Connecticut governors and state legislators.

The essence of it is that most real estate in New Haven, being owned by nominally nonprofit entities, is exempt from municipal property taxes; that most of this exempt property is owned by Yale; and that the university, while being New Haven's largest employer and the city's main reason for being, is less of a boon than generally thought.

According to the Hearst report, the university's taxable property in New Haven, property used mainly for commercial purposes, has total value of $173 million while its tax-exempt property, used mainly for educational purposes, is valued at around $4.4 billion.

Yale pays the city $5 million annually in taxes on its taxable properties and another $22 million or so in voluntary payments for its exempt properties, or about $27 million. But without its property-tax exemption Yale would owe New Haven as much as $146 million more than the university pays now.

Of course there's no denying Yale's enormous economic contribution to New Haven and its suburbs. Without Yale, New Haven would be Bridgeport, whose reason for being, as long assumed by state government, is mainly to confine Fairfield County's poverty.

But Yale's relationship with New Haven has gotten far beyond disproportionate. As a political force the university is bigger than the city and, it seems, since state government has not acted against that disproportion, bigger than the whole state.

It's not that Yale can't afford to pay more; it has an endowment of around $40 billion, which even President Trump and the Republican majority in Congress have found the courage to begin taxing.

Nine years ago the General Assembly considered legislation to limit the university's tax exemption but did not act.

Yale has claimed that the charter that it received from Connecticut's colonial legislature in the 1700s gives the university permanent exemption from property taxes.

But the charter and its revisions under state law during the next two centuries put limits on Yale's tax exemption, the first limit being a mere 500 pounds sterling. The tax exemption was thought justified in large part because, in its early years, Yale was heavily subsidized by cash from state government and was a de-facto government institution. A remnant of this connection to state government is the continuing “ex-officio" membership of Connecticut's governor and lieutenant governor on the university's Board of Trustees.

Yale no longer gets a direct annual cash stipend from state government but its $173 million tax break is worth a lot more. That money is paid not just by New Haven's residents through their property taxes and rents but by all state taxpayers as well, since New Haven city government is so heavily subsidized by state government.

Even if the courts concluded that the university's charter, as amended over the years, puts it beyond all property taxes on educational buildings, state government could coerce Yale by restricting the acreage it owns in the city, thereby forcing it to sell property and rent it back.

Would Yale leave Connecticut if, as was proposed nine years ago, state law limited university property-tax exemptions to $2 billion per year, thereby raising Yale's annual tax bill by $70 million or so? Yale's huge endowment implies otherwise.

At least the new federal tax on large university endowments has not prompted the richest schools to start planning to leave the country.

The additional property-tax revenue paid by Yale could be divided equally between New Haven and state government, state government recovering its share by reducing its financial aid to the city.

Of course those governments probably wouldn't spend the windfall very well, but it's the principle of the thing.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Maybe from a dream while napping

“In Translation 3” (woven cotton paper, ink, acrylic and colored pencil mounted on panel), by Hetty Baiz, in the group show “Paper Work,’’ at the Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine, Sept. 13-Oct. 11.

Her Web site says her images:

“Appear to be fading into the surface, or perhaps emerging from it, and the identity of the subject is absorbed into the materiality. Open ended questions about transience and the nature of being – of identity, mortality, and time, are intrinsic to her work.’’

‘You can’t eat granite’

Granite quarry in Barre, Vt.

“They can have their granite. I’ll take the good clean earth for me…. People can get along without tombstones, but they can’t get along without food, they can’t get along without potatoes, eggs, milk, butter, bread, vegetables. You can’t eat granite.”

— Vermont farmer quoted in Men Against Granite, a selection of 55 interviews by Mari Tomasi conducted in 1938-1940 by the Federal Writers Project in Vermont.

Llewellyn King: Amidst immigration crisis, from special relationship to odd couple

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Through two world wars, it has been the special relationship: the linkage between the United States and Britain. A linkage forged in a common language, a common culture, a common history, and a common aspiration to peace and prosperity.

The relationship, always strong, was especially burnished by the friendship of President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Now it looks as though the special relationship has morphed into the odd couple.

Britain, it can be argued, went off the rails in 2016 when, by a narrow majority, it voted to pull out of the European Union.

With a negative growth rate, and few prospects of an economic spurt, Britons can now ponder the high price of chauvinism and the vague comfort of untrammeled sovereignty. Americans could ponder that, too, in the decades ahead.

Will tariffs -- which have already driven China, Russia and India into a kind of who-needs-America bloc -- be the United States’ equivalent of Brexit? An economic idea which doesn’t work but has emotional appeal. An idea that is isolating, confining and antagonizing.

A common thread in the national dialogues is immigration.

Britain is swamped. It is dealing with an invasion of migrants that has changed and continues to change the country.

In 2023, according to the U.K.’s Office for National Statistics, 1.326 million migrants moved to Britain; last year, the number was 948,000. There has been a steady flow of migrants over the past 50 years, but it has increased dramatically due to wars around the globe.

Among European countries, Britain, to its cost, has had the best record for assimilating new arrivals. It is a migrant heaven, but that is changing with immigrants being blamed for a rash of domestic problems, from housing shortages to vastly increased crime.

In the 1960s, Britain had very little violent crime and street crime was slight. Now crime of all kinds -- especially using knives -- is rampant, and British cities rival those across America -- although crime seems to be declining in America, while it is rising in Britain.

Britain has a would-be Donald Trump: Nigel Farage, leader of the Reform UK party, which is immigrant-hostile and seeks to return Britain to the country it was before migrants started crossing the English Channel, often in small boats.

Farage has been feted by conservatives in Congress, where he has been railing against the draconian British hate-speech laws, which he sees as woke in overdrive.

Britain has been averaging 30 arrests a day for hate speech and related hate crimes, few of which result in convictions.

Two recent events highlight the severity of these laws. Lucy Connolly, the 42-year-old wife of a conservative local politician, took issue with the practice of housing immigrants in hotels; she said the hotels should be burned down. Connolly was sentenced to 31 months in jail. She has been released, after serving 40 percent of her sentence.

A very successful Irish comedy writer for British television, Graham Linehan, posted attacks on transgender women on X. On Sept. 1, after a flight from Arizona, he was met by five-armed policemen and arrested at London’s Heathrow Airport.

Britain’s hate laws, which are among the most severe in the world, run counter to a long tradition of free speech, dating back to the Magna Carta, in 1215. An attempt to get more social justice has resulted in less justice and abridged the right to speak out. A crisis in a country without a formal constitution.

On Sept. 17, President Trump is due to begin a state visit to Britain. Fireworks are expected. Trump’s British supporters, despite Farage and his hard-right party, are still few and public antipathy is strong.

Trump, for his part, will seek to make his visit a kind of triumphal event, gilded with overnight posts on Truth Social on how Britain should emulate him.

The British press will be ready with vituperative rebukes; hate speech be damned.

It is unlikely that the Labor government, whose membership is as diverse and divided as that of the Democratic Party, will find anything to call hate speech about attacks on Trump. A good dust-up will be enjoyed by all.

Isolated, the odd couple have each other.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

‘Memory and sensation’

“double spiral (blooms)’’ (oil on canvas), by Beverly Acha, in the group show “Making Space,’’ at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum & Art Center, through Nov. 2.

The museum says:

“Beverly Acha’s pastels and oil on canvas use an abstract visual language that she initially developed through observing her day-to-day surroundings, referencing architectural structures, scientific diagrams, the botanical world, and landscape. Acha’s works express memory and sensation as richly hued forms that vibrate with energy, creating a charged atmosphere with deceptively simple means. She asks us to examine our own awareness of the spaces around us and how we make sense of time, memory, and movement.’’

New England Youth Theatre, in Brattleboro.

Before Trump went after it

Harvard Square in 2015

“I just remember getting really drunk {in Harvard Square} and spending a lot of time trying to pick up a waitress. She went to Harvard. I was really impressed….Because, if you’re over at B.U., or if you’re at any school in this area that isn’t Harvard, you have an inferiority complex which I developed to a full-on resentment.’’

— Marc Maron (born 1963), stand-up comedian and podcaster

Map of Harvard Square in 1873

They’re up there to help

“Smoky Panorama” (archival pigment print hand-colored with pastels), by Helen Glazer, in the show “Clouds: A Collaboration with Fluid Dynamics,’’ an group exhibit of cloud photography at the William Benton Museum of Art, in Storrs, Conn., through Dec. 14.

The museum says that although clouds are “often physically far away from life on the Earth’s surface, clouds support life on the planet. We may take them for granted, but like art, we need clouds." This exhibition is presented in collaboration with the University of Connecticut College of Engineering and Professor Georgios Matheou, who recently received a National Science Foundation award for his work on clouds.

It can be very fluid

Installation image from Carlie Trosclair’s show “the shape of memory,’’ at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, Rockland, through Sept. 14.

— Photo by Dave Clough

The gallery says:

“Metaphor is essential to Carlie Trosclair’s work: architecture as body, architectural surface as skin, latex as skin, the domestic space as a vessel of memory and past lives. The resulting sculptures and installations explore the vulnerability and ephemerality of home, as both a physical space and a concept. The poetic takes on a visceral existence in Trosclair’s ghostly sculptures—created by painting liquid latex onto man-made and natural surfaces, allowing it to dry, and then peeling it away. The milky liquid (tapped from rubber trees), applied in multiple layers, dries to a translucent amber.

“At times, the latex picks up color from the original surface; in other works, the artist adds natural pigment to suggest the passage of time.

“Trosclair, the daughter of an electrician, recalls spending her childhood in historic New Orleans residential properties at varying stages of construction and renovation. These memories go hand in hand with the impacts of the Gulf Coast climate, where one is perpetually subjected to evacuation and uncertain return. The repeated act of leaving home and belongings behind led Trosclair to consider closely the haptics of memory and the psychology of place. In recent work, Trosclair expands the notion of regenerative cycles and home beyond the built environment, exploring a symbiotic relationship with the broader landscape.’’

Germán Reyes: Don’t panic about college students’ use of AI

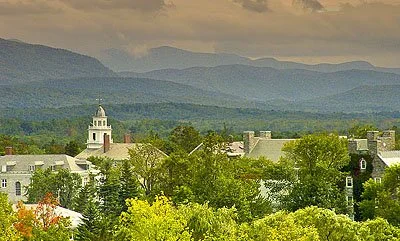

Tower of Old Chapel of Middlebury College, with the Green Mountains in the distance.

— Photo by Dogstarsail

From The Conversation Web site, except for photo above

Germán Reyes is an assistant professor of economics at Middlebury College

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

MIDDLEBURY, Vt.

More than 80% of students at Middlebury College, which is considered elite, use generative artificial intelligence for coursework, according to a recent survey I conducted with my colleague and fellow economist Zara Contractor. This is one of the fastest technology- adoption rates on record, far outpacing the 40% adoption rate among U.S. adults, and it happened in less than two years after ChatGPT’s public launch.

Although we surveyed only one college, our results align with similar studies, providing an emerging picture of the technology’s use in higher education.

Between December 2024 and February 2025, we surveyed over 20% of Middlebury College’s student body, or 634 students, to better understand how students are using artificial intelligence, and published our results in a working paper that has not yet gone through peer review.

What we found challenges the panic-driven narrative around AI in higher education and instead suggests that institutional policy should focus on how AI is used, not whether it should be banned.

Contrary to alarming headlines suggesting that “ChatGPT has unraveled the entire academic project” and “AI Cheating Is Getting Worse,” we discovered that students primarily use AI to enhance their learning rather than to avoid work.

When we asked students about 10 different academic uses of AI – from explaining concepts and summarizing readings to proofreading, creating programming code and, yes, even writing essays – explaining concepts topped the list. Students frequently described AI as an “on-demand tutor,” a resource that was particularly valuable when office hours weren’t available or when they needed immediate help late at night.

We grouped AI uses into two types: “augmentation” to describe uses that enhance learning, and “automation” for uses that produce work with minimal effort. We found that 61% of the students who use AI employ these tools for augmentation purposes, while 42% use them for automation tasks like writing essays or generating code.

Even when students used AI to automate tasks, they showed judgment. In open-ended responses, students told us that when they did automate work, it was often during crunch periods like exam week, or for low-stakes tasks like formatting bibliographies and drafting routine emails, not as their default approach to completing meaningful coursework.

Of course, Middlebury is a small liberal-arts college with a relatively large portion of wealthy students. What about everywhere else? To find out, we analyzed data from other researchers covering over 130 universities across more than 50 countries. The results mirror our Middlebury findings: Globally, students who use AI tend to be more likely to use it to augment their coursework, rather than automate it.

But should we trust what students tell us about how they use AI? An obvious concern with survey data is that students might underreport uses they see as inappropriate, like essay writing, while overreporting legitimate uses like getting explanations. To verify our findings, we compared them with data from AI company Anthropic, which analyzed actual usage patterns from university email addresses of their chatbot, Claude AI.

Anthropic’s data shows that “technical explanations” represent a major use, matching our finding that students most often use AI to explain concepts.

Similarly, Anthropic found that designing practice questions, editing essays and summarizing materials account for a substantial share of student usage, which aligns with our results.

In other words, our self-reported survey data matches actual AI conversation logs.

Why it matters

As writer and academic Hua Hsu recently noted, “There are no reliable figures for how many American students use A.I., just stories about how everyone is doing it.” These stories tend to emphasize extreme examples, like a Columbia student who used AI “to cheat on nearly every assignment.”

But these anecdotes can conflate widespread adoption with universal cheating. Our data confirms that AI use is indeed widespread, but students primarily use it to enhance learning, not replace it. This distinction matters: By painting all AI use as cheating, alarmist coverage may normalize academic dishonesty, making responsible students feel naive for following rules when they believe “everyone else is doing it.”

Moreover, this distorted picture provides biased information to university administrators, who need accurate data about actual student AI usage patterns to craft effective, evidence-based policies.

What’s next

Our findings suggest that such extreme policies a blanket bans or unrestricted use carry risks.

Prohibitions may disproportionately harm students who benefit most from AI’s tutoring functions while creating unfair advantages for rule breakers. But unrestricted use could enable harmful automation practices that may undermine learning.

Instead of one-size-fits-all policies, our findings lead me to believe that institutions should focus on helping students distinguish beneficial AI uses from potentially harmful ones. Unfortunately, research on AI’s actual learning impacts remains in its infancy – no studies I’m aware of have systematically tested how different types of AI use affect student learning outcomes, or whether AI impacts might be positive for some students but negative for others.

Until that evidence is available, everyone interested in how this technology is changing education must use their best judgment to determine how AI can foster learning.

John O. Harney: My late-summer reflections on the Rose Kennedy Greenway

In the Rose Kennedy Greenway.

— Photo by John O. Harney

Greenway from above.

BOSTON

Worry of the day: What if ICE raids the peaceful Rose Kennedy Greenway, in downtown Boston, on a hot summer day and mistakes me in my bucket hat for an immigrant landscaper theoretically ripe for abduction?

In case I join the disappeared, here are some late-summer 2025 reflections on the Greenway.

Before a recent visit to observe blooms there, I enjoyed lunch in a fellow volunteer’s backyard garden on Beacon Hill’s Joy Street. The lunch is to honor semi-retiring horticulture staffer Darrah Cole, who first introduced me to Greenway phenology.

The back garden, complete with a small ornamental pool — more suited for foot-soaking than swimming —reminded me of a similar preserve I saw last year at the South End Garden Tour — another beautiful private space in a place that you might think would/should be public.

I wonder why, among all the prize specimens I see on the Greenway, I am especially taken by the humble fleabane, which is common on New England roadsides?

This time, the tiny daisy-like flower’s usually white petals are slightly bluish. A friend suggests that I like it because it’s a “working-class flower.” A high compliment, I think.

In my own yard, I ponder why bouncing bets are less precious than pink lady slippers. And why are milkweeds and spiderworts dissed for the conditions they prefer? A sort of phenological version of haves and have-nots.

Gourdy pod season

Late summer is a challenging season for tracking blooms on the Greenway. The flowers of the bigleaf magnolia give way to gourdy cones. The yellow-twig dogwood (or is it red- or blood-twig?) shows white berries. Milkweed shows pods, filled with fluffy floss to be carried in the wind. The pawpaw of nursery rhyme now bears “custard apples.”

The peak score on the Greenway ranking scale is 3, with 2 suggesting headed toward peak and 4 indicating on the downswing. If it were a flower being judged, a 4 might signify browning. But a fruit or a cone, who knows?

I tend to cover my bases, noting on my scoresheet, “the fruit/berry/pod dilemma, 2 or 4?”

These colors run

I can’t resist touching the leaves of the wintergreen plant in a stone container near the Red Line Plaza. The small plant’s scent brings back childhood memories of Canada Mints, sometimes carried in my father’s pockets.

Coneflowers put on a show of light and dark pinks. Away from the Greenway, I keep seeing these plants plugged as easy color for your garden. But in my own yard, the flowers are eaten by rabbits within a day of planting.

Anemones now show very few yellow-centered white flowers along Pearl Street. And many of the ones nearer Congress Street have now turned to pompoms that look almost like cotton balls.

I see that irises are no longer flowering in the bed near Atlantic and Pearl. The liliums that in the preflowering stage I mistook for tigerlilies impressed me for a fleeting period with their vibrant white and pink flowers. They’re now bloodshot.

Alliums still show globe flowers but have lost their pink, purple and white showiness and now look brownish. The flowers of their cousin, the common chive, have retained a little of their pink-purple color.

Dicentra formosa shows pink bleeding hearts after weeks of yellowing. Also bucking the troublesome ranking system, dicentra’s hearts disappear one week, then burst back on the scene the next.

Nearby, a large rathole (hardly the only one on the Greenway) appears on Parcel 21 near my beloved umbrella pine. One source suggests that the hole could be the work of toads or cicadas. I’d like that.

Daylilies flowering deep red are a shock compared with the more common oranges and yellows. Most of the latter are now passed but show interesting green seed packets.

Various hydrangeas show ever-less vibrant white or pale blue flowers, including one that has shown white, pink and bluish flowers all at once.

Evolutionary roads

I am still surprised to see crepe myrtle blooming on The Greenway in a parcel near the wharves. I always thought that it was a Southern thing. Inspired by the Greenway’s confidence, I recently bought two small crepe myrtles for my own garden. We’ll see how fast climate change makes them thrive or die in our shifting heartiness zone.

Dracunculus shows an open pod of pea-like fruits (clearly, a reseeding strategy, I think). Eryngium planum shows thistle-like balls almost as respectable as echinops. Black elderberry shows flower clusters, but the white color of the flower and black of the berry is fading. When do they make the wine?, I wonder.

I’ve paid scant attention to the grasses on my parcels, but I’m coming around to their forms from wispy to shrub-like. Between the mural vent and Congress Street, I identify (perhaps incorrectly?) fountain grass shooting out white fronds, which I’ve seen described aptly as a “swollen finger?”

Joe Pye weed is tall and showing pinkish flowers near the rain garden. Cutleaf coneflowers rise tall, flowering yellow inside the small park near the Night Shift (I once thought that they were Jerusalem artichokes). Menthe shows small white flowers and gives a minty smell upon the brush of a hand.

Tall Culver’s root shoots out white veronica-like spikes. Filipendula rubra blooms pink, but increasingly rusty-looking, flowers in the center of tall light-green foliage. In a raised bed, marigolds flower orange and yellow and lavenders purplish. Near the highway underpass wall, false and real sunflowers shine bright yellow. Sweet pea and honeysuckle vines flower vibrant pink and a bit of orange, and eggplant shows small dangling fruits along the wall to the tunnel.

In addition, the flowering raspberry blooms nice pink flowers near a cast-iron bucket. Pineapple sage shows a few strong red flowers. Cardoon shows spiky flowers vaguely familiar from bottles of Cynar, the Italian liqueur made from cardoon’s cousin, the artichoke. Zinnias flower strong dark and light pink in bed with great blue lobelia. Queen Anne’s lace displays white umbrels with a slight pinkish hue — another New England roadside favorite. I should check next time to see if they have the single black flower (some say purple) in the center of their heads that my daughter-in-law Nastya taught me about. If not, I could be seeing the similar-looking poison hemlock!

John O. Harney is a Boston-area writer. For more than 30 years, he was the executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education. In 2023, he left the editorship and began volunteering in phenology at the Rose Kennedy Greenway and in English-language teaching at the Immigrant Learning Center in Malden, Mass. Also see A Volunteer Life and Back to Green and Witnessing Beauty but Wilting in Empathy and What To a Volunteer is Labor Day? and Spring Has Sprung.

Philip K. Howard: A program for American revival

This is a lightly edited version of a press release touting my old friend Philip K. Howard’s latest book. The New York-based lawyer, civic leader and photographer is chairman of the nonprofit reform organization Common Good.

(Editor’s note: For an an example of how much we need regulatory streamlining, see the long delays in fixing the Washington Bridge over Rhode Island’s Seekonk River.)

In Saving Can-Do: How to Revive the Spirit of America civic philosopher Howard proposes a governing framework to revive America’s can-do culture — not by DOGE’s Indiscriminate Cuts, and nor by “Abundance”.

Saving Can-Do shows why the waste and paralysis of the red-tape state can be cured only by a new governing framework that empowers human responsibility on the spot. Letting Americans use common sense also holds the key to relieving populist resentment.

This brief book, to be published by Rodin Books on Sept. 23, responds to Americans’ desire for government that delivers results, not overbearing red tape.

“Washington needs to be rebooted, but neither party presents a vision to do this,” Howard notes.

“Republicans focus on cutting programs, not making them work. Democrats want to throw more money at a failing system. Aspiring to abundance is important, but escaping bureaucratic quicksand requires a radical shift in governing philosophy — replacing the red-tape compliance system with a framework activated by human responsibility.”

All societies periodically undergo a major shift in the social order. America is at one of those moments of change, and needs a coherent new overhaul vision to avoid the risks of extremism.

President Trump is swinging a wrecking ball at the status quo, but has no plan for how Washington will work better the day after DOGE. Democrats are in denial, waiting their turn to run a bloated government that Americans increasingly loathe.

Saving Can-Do offers a dramatically simpler governing vision: Replace red tape with responsibility. Let Americans use their judgment. Let other Americans hold them accountable for their results and their values.

“The geniuses in the 1960s tried to create a government better than people,” Howard says. “Just follow the rules. Or prove that your judgment about someone is fair. But how do you prove who has poor judgment, or doesn’t try hard? Bureaucracy makes people go brain dead—so focused on mindless compliance that they can’t solve the problem before them. Americans hate it.”

“We must scrap the red tape state,” argues Howard. “New leadership is not sufficient, because the new leaders will be shackled by rigid legal mandates. Trying to prune the red tape still leaves a jungle of other mandates.’’

“What’s required is a multi-year effort to replace command-and-control bureaucracies with simpler codes that delineate the authority to make tradeoff judgments. The idea is not radical, but traditional— it’s the operating philosophy of the U.S. Constitution. As America approaches the 250th anniversary of the revolution, it’s time to reclaim the magic of America’s unique can-do culture.”

For more information, please contact Henry Miller at hmiller@highimpactpartnering.com.

We could use more fantasy

“Fantasy Landscape’’ (oil on canvas), circa 1911, by Howard Gardiner Cushing, in the show “Howard Gardiner Cushing: A Harmony of Line and Color,’’ through Dec. 31, at the Newport Art Museum.

This is the first major retrospective in decades of Cushing (1869-1916), one of the Gilded Age’s most visionary— and overlooked—American artists.

The exhibition brings together over 55 paintings, many of which have not been publicly exhibited in more than 60 years.

Probably friendlier than Walmart

“Coburns General Store” (oil on canvas), in South Strafford, Vt., by Jennifer Brown, at Matt Brown Fine Art, Lyme, N.H.

‘Fuddled age’

Photo taken from the French King Bridge, which connects Erving and Gill, Mass., over the Connecticut River, on the Mohawk Trail.

— Photo by -jkb-

“Time slips indenture, backing age

on fuddled age, confusing fall

with summer-snow with hawthorn flurries,

apple flakes along black boughs.

North of Boston, fire falls

from tree to tree, and leaf by leaf

perverse New England springs to bloom.’’

— From “The Fall,’’ by Joseph Bottum

Asters are associated with early September.

Local inflection

{Emily Dickinson, 1830-1886} wrote about nature, love, life, death, humanity’s relation with God — matters that from time to time occupy the thoughts of all thinking people. But her approach was always that of a New England villager…She wrote that she saw “New Englandly,’’ and she might just as accurately have expressed herself with another coinage, “Amherstly.’’

— From The New England Town in Fact and Fiction, by Perry D. Westbrook (1989)

‘Trapped memories’

From the Safarani sisters' new series of works, called “Submerged in Time,’’ at ShowUp Gallery, Boston, through Sept. 28. The works reflect efforts to deal with memories. The gallery notes: “Balloons and string lights seen through a translucent surface convey mystery and speak to the memories that exist in everyone’s life—those from our childhood or our unconscious. These memories may feel trapped or unclear, sometimes hidden behind a buffer we create to avoid remembering them clearly.’’

Intersecting systems

From “Intersecting Ecologies,’’ a two-person, collaborative exhibition by Paula Gerstenblatt and Jan Piribeck focused on the intersection of personal, social and environmental systems. The show runs on Sept. 5-Nov. 30, at The Parsonage gallery, Searsport, Maine. The work is situated in Maine and Greenland, where Gerstenblatt and Piribeck have worked as artists and researchers.

The Park-Griffin-Treat House, in Searsport, Maine, built for sea Captain Benjamin Bentley Park in 1840, during The Pine Tree State’s maritime heyday.

— Photo by Bruce C. Cooper