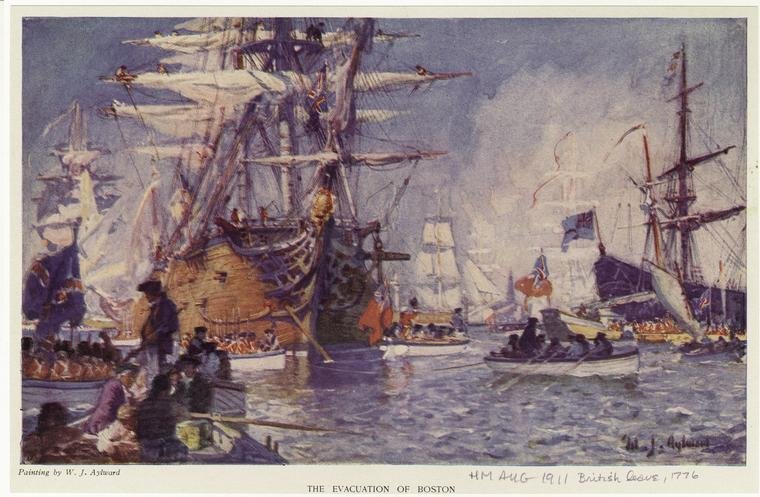

Mass. merchants’ revolution

The British prepare to evacuate Boston on March 17, 1776.

“The American Revolution was a remarkably successful revolution. It did not fall into chaos and violence, nor did it slide toward dictatorship. It produced no Napoleon…. It achieved its goals. It was also, as revolutions go, extremely unromantic. The radicals, the real revolutionaries, were middle-class Massachusetts merchants with commercial interests, and their revolution was about the right to make {lots of} money….

“The American Revolution was the first great anticolonialist movement. It was about political freedom. But in the minds of its most hard line revolutionaries, the New England radicals, the central expression of that freedom was the ability to make their own decisions about their economy.’’

Mark Kurlansky, in his book Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World

Architectural ennui

Work by Joan O'Beirne, in her show “Detachments,’’ on display at the Vermont Center for Photography, Brattleboro

— Image courtesy Vermont Center for Photography

The center says:

“Much of O'Beirne's work is ephemeral and dream-like, often using pinhole cameras and printing or projecting on unconventional surfaces. Collage and reusing found objects and old photos also play a role in her artistic practice.’’

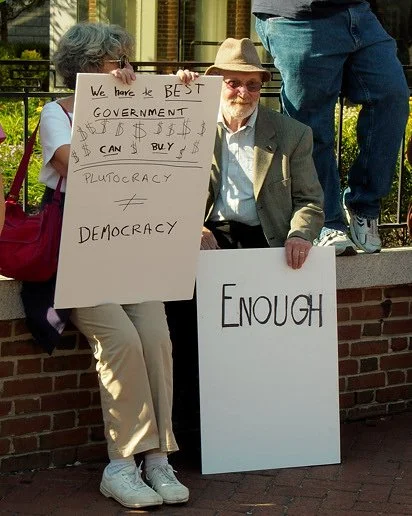

Lee Drutman: How ruthlessly cynical Republicans keep pulling off reverse Robin Hoods in spite of unpopular policies

Republicans just contorted their coalition to pass regressive tax and spending legislation that polling shows Americans oppose 2-to-1. It is bad, incoherent policy that most voters did not want. It is full of gimmicks. And yet. They still rushed to pass it.

Why?

Why did Republicans make this their signature achievement, despite the unpopularity and internal resistance? Will they actually pay any exceptional electoral penalty?

And most importantly: If Republicans don't pay any exceptional penalty for legislation that's both massively unpopular and internally divisive, what does that tell us about American politics.

I don't think Republicans will pay any exceptional penalty for this legislation (beyond the usual midterm penalty for the party in the White House).

I think there are three main reasons, all of which tell us important things about our politics. Let’s dive in.

Participation Gap: Who Votes vs. Who Gets Hurt

There will almost certainly be no lower-income voter backlash. Those most harmed by regressive policies participate least in electoral politics.

Roughly one in five Americans benefit from Medicaid. To qualify for Medicaid, your income needs to be pretty low—a little over the poverty level. And here in the United States, low-income voters participate at much lower rates than higher income voters. Much lower.

Hit this link to see my chart on this gap.

What explains the income-turnout gap?

Well, as a general rule, across countries, the more unequal the society, the higher the gap. Mostly, this is because the more unequal the society, the more low-income voters think: What’s the point? It doesn’t matter whether I vote or not, nothing changes.

This creates a vicious cycle Republicans exploit.

And the U.S. is a real outlier here in the income-turnout gap. American Exceptionalism, indeed. The figure below comes from an informative paper by Matthew Polacko, “Inequality, policy polarization and the income gap in turnout”

However, this doesn't fully explain Republican confidence. Some middle-class voters do participate regularly and care deeply about these programs. The challenge is that even engaged voters face genuine difficulties tracing policy effects to political decisions.

Policy Design Magic: Timing and Traceability.

Republicans have done something clever with this bill: Frontload the popular stuff, delay the unpopular stuff. Tax benefits go into effect first. Social-spending cuts go into effect later. In 2026, when voters file their taxes, they'll see the benefits. Trump and fellow Republicans will talk up these benefits. Most will go to the very rich, but if most taxpayers get something, they'll see the benefits in their own returns. People generally like paying lower taxes.

By contrast, the most unpopular parts—the cuts to Medicaid—won't go into effect until after the 2026 mid-terms. Until the cuts happen, it's harder to campaign against them.

Long timing also confuses “traceability." Apparently, Republicans have read R. Douglas Arnold's political science classic, The Logic of Congressional Action, which explains the importance of policy design: Make the benefits visible and obscure the costs. The less traceable the costs, the harder for the public to know who to blame. Who knows, by 2026, Republicans might be blaming Democrats for the cuts!

Even more: The connection between federal Medicaid cuts and recipients’ care isn't immediately obvious, especially since states often don't call their programs “Medicaid, instead using names such as SoonerCare in Oklahoma, Apple Health in Washington, or TennCare in Tennessee. Nearly all states use private insurance companies to run their Medicaid programs, meaning beneficiaries hold insurance cards from UnitedHealth or Blue Cross Blue Shield, further obscuring the federal program's role.

Confusing policy makes traceability hard.

Politics is more about status than materialism

Democrats are constantly talking about money and benefits and costs. But one of the funny things about us humans is that we don't actually care that much about how much money we have in the abstract. We care about how we're doing relative to others who we think are below us. We're deeply wired for status. What we care about is: Are we doing better than the people we should be doing better than? We're much more motivated to avoid falling below others than we are to rise above them.

So we don't vote in our economic self-interest—we vote in our status interest. (Tali Mendelberg has a great essay on the centrality of status in politics, “Status, Symbols and Politics”)

The more we feel like we're in a zero-sum contest for resources, the less we care about absolute numbers, and the more we care about relative status. This is the conflict Republicans are driving. It's compelling because it's a story. It grabs our attention. It's far more compelling than wonky policy details.

As Vice President J.D. Vance wrote on X: "Everything else—the CBO score, the proper baseline, the minutiae of the Medicaid policy—is immaterial compared to the ICE money and immigration enforcement provisions."

And he’s probably right. This is the Republican playbook under Trump. It's one of the oldest political stories: the barbarians are at the gates, and unless we fight back, they will undermine everything good about our civilization. It plays on deep-seated fears about identity and status and freedom.

It may not be “rational" in the way highly educated liberals like me are taught to think about rationality. But it is a story in which “ordinary Americans" get to feel like heroes, preserving American greatness for future generations. It promises something greater than materialism. It promises a boost in status.

Democrats often call out this chicanery and try to get people to focus on details. But people don’t care about details, unless they fit into a larger story. But Democrats lack a competing narrative or defining conflict. They talk in abstract numbers about this many people who will be knocked into poverty, or have their Medicaid cut off. It’s all very clinical.

I think this explains why Republicans can confidently pass unpopular legislation. They understand that voters respond to status signals and moral categories more than policy outcomes. When the immigration narrative promises to restore proper hierarchies and defend cultural boundaries, it overwhelms concerns about health-care cuts or tax inequity. The psychology of relative position trumps the math of absolute benefits.

One way Democrats could respond: make politics more explicitly about morality

But what if Democrats approached politics differently? What if they framed the conflict much more explicitly in moral terms. Moral appeals can be more powerful than economic appeals. Research shows moral appeals generate pride, hope and enthusiasm that inspire political mobilization.

When people have given up on politics because “nothing changes," a story about fundamental dignity and respect might cut through fatalistic assumptions in ways that policy promises never could.

Outrage at cruelty and indignity doesn't require understanding complex policy mechanics or waiting for delayed implementation. It's immediately comprehensible and emotionally compelling, potentially disrupting the careful attention management that Republicans depend on. When voters feel their fundamental values are under attack, policy complexity becomes irrelevant.

Fighting for “dignity and decency" reframes political conflict as “dignity vs. cruelty" and “decency vs. indecency.” If Democrats engage in a real moral fight here, they could link regressive economic policy to harsh treatment of immigrants to Trump’s grotesque White House corruption.

The hard part is to make it authentic, to channel outrage into a compelling story that disengaged voters can get excited about.

This goes against the main current in the Democratic Party — an overly intellectualized framework that treats politics as fundamentally rational, backed up by a consultant-polling complex that optimizes individual messages while missing the larger narrative. Individual policy messages don’t land if they don’t fit a larger narrative conflict.

The problem is that moral conviction can't be A/B tested. Moral conviction requires the kind of political risk-taking that threatens both consultant fees and carefully managed coalitions.

But I do think Democrats should lean into “Dignity and Decency” – it feels right to me.

Something fundamental about electoral democracy is operating differently than we thought.

So yes, this monstrosity of a bill Republicans passed is widely unpopular. It's also bad policy. But if I had to guess, Republicans will not pay any exceptional electoral penalty for it. By October 2026, political attention will be elsewhere. Democrats may win back the House, but it won't be a wave. Republicans will probably hold the Senate.

So, to get back to my original question: if Republicans indeed do not pay any exceptional electoral penalty for a massively unpopular and regressive tax and spending bill, what does that tell us about American politics?

I think this tells us that individual policies and their popularity matter very little to how voters decide, and far less than we think they should. It may also tell us that tax and spending policy matter very little to how voters decide. It should also tell us that materialism matters much less than we think. And if so, it means we need to think about politics in different ways than we have been.

I think it means that we need to think about politics in terms of master narratives and dominant conflicts. And in terms of how our brains actually make sense of reality. And not the ways in which a generation of economists and economics-envying social scientists have tried to fit our brains into one-dimensional simplifications of ideology.

When a carnival barker salesman candidate can survive scandals, criminal indictments, policy unpopularity, and institutional opposition while mobilizing millions of voters, something fundamental about electoral democracy is operating differently than we thought. We should figure out what.

http://newamerica.org › our-people › lee-drutman

Lee Drutman is a senior fellow in the Political Reform program at New America. He’s the author of Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop.

College priorities

The former Ames mansion was the first building of the Stonehill College campus. The Ames family money came from its shovel factory.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Citizens in other “advanced” nations are astounded by how much money, energy and attention is expended at American colleges and universities on sports. Some of the bigger of these institutions are far more identified as sports-team businesses than as places for scholarship, with some “student athletes’’ paid for playing. More cultural corruption.

Consider tiny Stonehill College, in Easton, Mass. The largest gift in the nice little Catholic school’s history -- $15 million from alumni Thomas and Kathleen Bogan -- will go to helping to build new basketball and hockey arenas in a complex to be named for the Bogans, not to academics.

Stonehill seems to be in pretty good shape, financially and otherwise. But what’s going to happen to all those bucolic campuses around America as colleges close as the number of potential students continues to shrink with a declining birth rate and, sadly, as so many doubt the advantages of a liberal-arts education.

Christian Koulichkov is a managing director at Hilco Real Estate, where he helps closed colleges sell their campuses. He told Bloomberg News: “This is the next big land grab in the United States. There’s going to be thousands and thousands of acres with no plan. People never thought these things could disappear.”\

Far from the maddening crowd

“I Walked Far Down the Beach” (oil on canvas), by Shirley Cean Youngs, at Lily Pad East gallery, in very rich summer place Watch Hill, R.I.

‘Brief moments of clarity’

“Eco+Terrestre,’’ by Hillel O’Leary, at Boston Sculptors Gallery, through July 13.

The artist says:

“My sculpture, installation and public works are snapshot accretions capturing brief moments of clarity in a continuing process of navigating an increasingly turbulent world. They are an attempt to make meaning between the familiar and otherworldly, while provoking gut-feelings of tension, connection, loss, and wonder, through obfuscation, abstraction and interpretation of material history and culture. This work centers precarity as the coming state of everything, and with it, I hope to bring a level of urgency to a sense of self-reflection that is needed if we are to look beyond the way things have always been.’’

Frank Carini: N.E. freshwater fishing in hot water

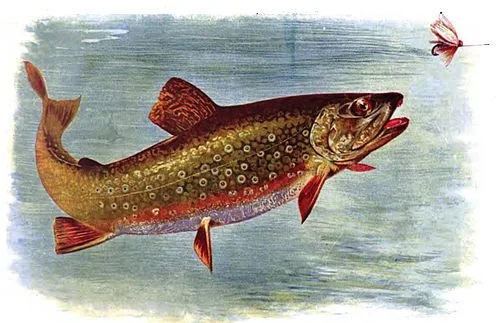

Eastern brook trout chasing an artificial fly, as illustrated in American Fishes (1903)

Excerpted (except for picture above) from an article in an ecoRI News series by Frank Carini. The series reports on how the region’s collection of native species is under threat on several fronts, most notably from humanity’s shortsightedness. Humans aren’t giving the natural world the space it needs and deserves. We’re crowding out nonhuman life, which, in turn, makes nature less productive and us less healthy. Wild New England examines the animals and insects most at risk.

Warming waters, which correlates to lower oxygen levels, changes in stream flow, and exacerbates aquatic stressors such as algal blooms and polluted stormwater runoff, are a significant threat to freshwater ecosystems and the fish they host. As waters warm, cold-water species will be replaced by fish suited for warm waters, causing nonnative species to take over ecosystems.

The climate crisis impacts where fish can live and how they reproduce and grow. These changes impact warm-water and cold-water fish differently. Eastern brook trout, for instance, are dependent on cold-water habitats. But climate change — fueled by the burning of fossil fuels — is causing streams to warm, shrinking the species’ range.

Eastern brook trout are also sensitive to water pollution caused by fertilizer runoff and acid rainfall caused by air pollution. These impacts have resulted in water pH levels being too low to sustain them, according to the U.S Fish & Wildlife Service. These impacts are also making their habitat unsuitable and affecting their spawning capabilities.

Here’s the full article.

After Jay Gatsby’s green light went dark

At a pen shop in Penn Station, in Manhattan

— Photo by William Richards

Dana-Farber to hire 700 nurses

The quadrangle of Harvard Medical School and adjacent Longwood Medical and Academic Area buildings.

Edited from a New England Council report

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, in Boston, has announced its hiring plan for its new Longwood Medical and Academic Area hospital. The institute says that it will require nearly 2,500 new employees, including 700 additional nurses.

Dana-Farber will soon merge with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The current partnership with Brigham and Women’s Hospital is set to expire in 2028. The expanding staff will be a part of the new $1.7 billion cancer hospital, opening in the Longwood Medical and Academic Area.

Dana-Farber’s current facilities only have 30 inpatient beds, which will be significantly expanded upon its transition to Longwood.

These proposed additions are being used to staff its proposed 300-bed hospital, said Jeanine Rundquist, executive director of the Center for Clinical and Professional Development at Dana-Farber. “If you want to be on the cutting-edge of cancer care, this is the place to be, certainly in our region, if not nationally,” Rundquist said.

Trying to survive in the Russian Empire

“Mama Will Protect You,’’ in Albert Chasan’s (1930-2024) ongoing show, “Painting His Parents Lives,’’ at the Yiddish Book Center, Amherst, Mass.

The venue says:

“With an uncanny eye for a past he never experienced, Albert Chasan’s works bring to life the stories his parents shared about their childhoods in the Russian Empire. Also on view: Yiddish: A Global Culture.’’

Stephanie Otts: How N.E. fishing industry has changed since ‘The Perfect Storm’ film

From The Conversation (except for image above)

Stephanie Otts is director of the National Sea Grant Law Center, at the University of Mississippi.

She receives funding from the NOAA National Sea Grant College Program through the U.S. Department of Commerce. Previous support for her fisheries management legal research was provided by The Nature Conservancy.

Twenty-five years ago, The Perfect Storm roared into movie theaters. The disaster flick, starring George Clooney and Mark Wahlberg, was a riveting, fictionalized account of commercial swordfishing in New England and a crew who went down in a storm.

The anniversary of the film’s release, on June 30, 2000, provides an opportunity to reflect on the real-life changes to New England’s commercial fishing industry.

Fishing was once more open to all

In the true story behind the movie, six men lost their lives in late October 1991 when the commercial swordfishing vessel Andrea Gail disappeared in a fierce storm in the North Atlantic as it was headed home to Gloucester, Massachusetts.

At the time, and until very recently, almost all commercial fisheries were open access, meaning there were no restrictions on who could fish.

There were permit requirements and regulations about where, when and how you could fish, but anyone with the means to purchase a boat and associated permits, gear, bait and fuel could enter the fishery. Eight regional councils established under a 1976 federal law to manage fisheries around the U.S. determined how many fish could be harvested prior to the start of each fishing season.

Fishing has been an integral part of coastal New England culture since its towns were established. In this 1899 photo, a New England community weighs and packs mackerel. Charles Stevenson/Freshwater and Marine Image Bank

Fishing started when the season opened and continued until the catch limit was reached. In some fisheries, this resulted in a “race to the fish” or a “derby,” where vessels competed aggressively to harvest the available catch in short amounts of time. The limit could be reached in a single day, as happened in the Pacific halibut fishery in the late 1980s.

By the 1990s, however, open access systems were coming under increased criticism from economists as concerns about overfishing rose.

The fish catch peaked in New England in 1987 and would remain far above what the fish population could sustain for two more decades. Years of overfishing led to the collapse of fish stocks, including North Atlantic cod in 1992 and Pacific sardine in 2015.

As populations declined, managers responded by cutting catch limits to allow more fish to survive and reproduce. Fishing seasons were shortened, as it took less time for the fleets to harvest the allowed catch. It became increasingly hard for fishermen to catch enough fish to earn a living.

Saving fisheries changed the industry

In the early 2000s, as these economic and environmental challenges grew, fisheries managers started limiting access. Instead of allowing anyone to fish, only vessels or individuals meeting certain eligibility requirements would have the right to fish.

The most common method of limiting access in the U.S. is through limited entry permits, initially awarded to individuals or vessels based on previous participation or success in the fishery. Another approach is to assign individual harvest quotas or “catch shares” to permit holders, limiting how much each boat can bring in.

In 2007, Congress amended the 1976 Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act to promote the use of limited access programs in U.S. fisheries.

Ships in the fleet out of New Bedford, Mass. Henry Zbyszynski/Flickr, CC BY

Today, limited access is common, and there are positive signs that the management change is helping achieve the law’s environmental goal of preventing overfishing. Since 2000, the populations of 50 major fishing stocks have been rebuilt, meaning they have recovered to a level that can once again support fishing.

I’ve been following the changes as a lawyer focused on ocean and coastal issues, and I see much work still to be done.

Forty fish stocks are currently being managed under rebuilding plans that limit catch to allow the stock to grow, including Atlantic cod, which has struggled to recover due to a complex combination of factors, including climatic changes.

The lingering effect on communities today

While many fish stocks have recovered, the effort came at an economic cost to many individual fishermen. The limited-access Northeast groundfish fishery, which includes Atlantic cod, haddock and flounder, shed nearly 800 crew positions between 2007 and 2015.

The loss of jobs and revenue from fishing impacts individual family income and relationships, strains other businesses in fishing communities, and affects those communities’ overall identity and resilience, as illustrated by a recent economic snapshot of the Alaska seafood industry.

When original limited-access permit holders leave the business – for economic, personal or other reasons – their permits are either terminated or sold to other eligible permit holders, leading to fewer active vessels in the fleet. As a result, the number of vessels fishing for groundfish has declined from 719 in 2007 to 194 in 2023, meaning fewer jobs.

A fisherman unloads a portion of his catch for the day of 300 pounds of groundfish, including flounder, in January 2006 in Gloucester, Mass. AP Photo/Lisa Poole

Because of their scarcity, limited-access permits can cost upward of US$500,000, which is often beyond the financial means of a small businesses or a young person seeking to enter the industry. The high prices may also lead retiring fishermen to sell their permits, as opposed to passing them along with the vessels to the next generation.

These economic forces have significantly altered the fishing industry, leading to more corporate and investor ownership, rather than the family-owned operations that were more common in the Andrea Gail’s time.

Similar to the experience of small family farms, fishing captains and crews are being pushed into corporate arrangements that reduce their autonomy and revenues.

Consolidation can threaten the future of entire fleets, as New Bedford, Massachusetts, saw when Blue Harvest Fisheries, backed by a private equity firm, bought up vessels and other assets and then declared bankruptcy a few years later, leaving a smaller fleet and some local business and fishermen unpaid for their work. A company with local connections bought eight vessels from Blue Harvest along with 48 state and federal permits the company held.

New challenges and unchanging risks

While there are signs of recovery for New England’s fisheries, challenges continue.

Warming water temperatures have shifted the distribution of some species, affecting where and when fish are harvested. For example, lobsters have moved north toward Canada. When vessels need to travel farther to find fish, that increases fuel and supply costs and time away from home.

Fisheries managers will need to continue to adapt to keep New England’s fisheries healthy and productive.

One thing that, unfortunately, hasn’t changed is the dangerous nature of the occupation. Between 2000 and 2019, 414 fishermen died in 245 disasters.

Llewellyn King: Low-lying wind turbines could be revolutionary

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Jimmy Dean, the country musician, actor and entrepreneur, famously said: “I can’t change the direction of the wind, but I can adjust my sails to always reach my destination.”

A new wind turbine from a California startup, Wind Harvest, takes Dean’s maxim to heart and applies it to windpower generation. It goes after untapped, abundant wind.

Wind Harvest is bringing to market a possibly revolutionary but well-tested vertical axis wind turbine (VAWT) that operates on ungathered wind resources near the ground, thriving in turbulence and shifting wind directions.

The founders and investors – many of them recruited through a crowd-funding mechanism — believe that wind near the ground is a great underused resource that can go a long way to helping utilities in the United States and around the world with rising electricity demand.

The Wind Harvest turbines would not be used to replace nor compete with the horizontal axis wind turbines (HAWT), which are the dominant propeller-type turbines seen everywhere. These operate at heights from 200 feet to 500 feet above ground.

Instead, these vertical turbines are at the most 90 feet above the ground and, ideally, can operate beneath large turbines, complementing the tall, horizontal turbines and potentially doubling the output from a wind farm.

The wind disturbance from conventional tall, horizontal turbines is additional wind fuel for vertical turbines sited below.

Studies and modeling from CalTech and other universities predict that the vortices of wind shed by the verticals will draw faster-moving wind from higher altitude into the rotors of the horizontals.

For optimum performance, their machines should be located in pairs just about 3 feet apart and that causes the airflow between the two turbines to accelerate, enhancing electricity production.

Kevin Wolf, CEO and co-founder of Wind Harvest, told me that they used code from the Department of Energy’s Sandia National Laboratory to engineer and evaluate their designs. They believe they have eliminated known weaknesses in vertical turbines and have a durable and easy-to-make design, which they call Wind Harvester 4.0.

This confidence is reflected in the first commercial installation of the Wind Harvest turbines on St. Croix, one of the U.S. Virgin Islands in the Caribbean. Some 100 turbines are being proposed for construction on a peninsula made from dredge spoils. This 5-megawatt project would produce 15,000 megawatt hours of power annually.

All the off-take from this pilot project will go to a local oil refinery for its operations, reducing its propane generation.

Wolf said the Wind Harvester will be modified to withstand Category 5 hurricanes; can be built entirely in the United States of steel and aluminum; and are engineered to last 70-plus years with some refurbishing along the way. Future turbines will avoid dependence on rare earths by using ferrite magnets in the generators.

Recently, there have been various breakthroughs in small wind turbines designed for urban use. But Wind Harvest is squarely aimed at the utility market, at scale. The company has been working solidly to complete the commercialization process and spread VAWTs around the world.

“You don’t have to install them on wind farms, but their highest use should be doubling or more the power yield from those farms with a great wind resource under their tall turbines,” Wolf said.

Horizontal wind turbines, so named because the drive shaft is aligned horizontally to the ground, compared to vertical turbines where the drive shaft and generator are vertically aligned and much closer to the ground, facilitating installation, maintenance and access.

Wolf believes that his engineering team has eliminated the normal concerns associated with VAWTs, like resonance and the problem of the forces of 15 million revolutions per year on the blade-arm connections. The company has been granted two hinge patents and four others. Three more are pending.

Wind turbines have a long history. The famous eggbeater-shaped VAWT was patented by a French engineer, Georges Jean Marie Darrieus, in 1926, but had significant limitations on efficiency and cost-effectiveness. It has always been more of a dream machine than an operational one.

Wind turbines became serious as a concept in the United States as a result of the energy crisis that broke in the fall of 1973. At that time, Sandia began studying windmills and leaned toward vertical designs. But when the National Renewable Energy Laboratory assumed responsibility for renewables, turbine design and engineering moved there; horizontal was the design of choice at the lab.

In pursuing the horizontal turbine, DOE fit in with a world trend that made offshore wind generation possible but not a technology that could use the turbulent wind near the ground.

Now, Wind Harvest believes, the time has come to take advantage of that untouched resource.

Wolf said this can be done without committing to new wind farms. These additions, he said, would have a long-projected life and some other advantages: Birds and bats seem to be more adept at avoiding the three-dimensional, vertical turbines closer to the surface. Agricultural uses can continue between rows of closely spaced VAWTs that can align fields, he added.

Some vertical turbines will use simple, highly durable lattice towers, especially in hurricane-prone areas. But Wolf believes the future will be in wooden, monopole towers that reduce the amount of embodied carbon in their projects.

One way or another, the battle for more electricity to accommodate rising demand is joined close to the ground.

This article was originally published on Forbes.com

On X: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King, based in Rhode Island, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant.

With horse as backup

“Main Street, c. 1940” (oil on canvas), by Nicholas Comito (1906-1995), at the Southern Vermont Arts Center, Manchester, Vt.

Fun, if slow

The Newport and Narragansett Bay Railroad yard in Melville, R.I., in April 2023.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It was very pleasant to see that the 13-mile long Newport & Narragansett Bay Railroad is providing passenger service on its scenic route on Aquidneck Island. That’s especially given that we’re approaching high tourist season. Of course, people will use this slow-moving service for fun, and not for any practical reason.

The train might slightly cut down on car traffic on the crowded island. What would cut it much more would be a railroad bridge connecting Tiverton, on the mainland, and Portsmouth, such as the one that was closed in 1988 and removed in 2006–07.

How great it would be if we could take the train to Newport from Providence and Boston!

Chris Powell: Murphy smears the Conn. ‘war industry’

Electric Boat’s submarine-construction facility in Groton, Conn.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

To hear Connecticut U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy tell it, President Trump dispatched Air Force bombers and Navy submarines to destroy Iran's nuclear bomb-making facilities because the “war industry" is so influential in Washington.

On the leftist-leaning MSNBC cable television network the other day, the senator agreed with his interviewer's suggestion that there was a big gap between the opinion of Democratic members of Congress and the opinion of ordinary Democrats about the attack on Iran, with Democrats in Congress far less opposed to it than ordinary party members.

“There is a war industry in this town," Murphy said of Washington. “There’s a lot of people who make money off war. The military -- I love them, they're capable -- but they are always overly optimistic about what they can do. ... The war industry spends a lot of money here in Washington telling us that the guns and the tanks and the planes can solve all our problems."

“All our problems"? That was hyperbole worthy of President Trump.

Of course there is a "military-industrial complex," as President Dwight D. Eisenhower warned as he left office in January 1961. But it just wants its products to be manufactured and purchased by the government and cares little about whether they are actually used.

Contrary to Murphy's suggestion, Trump didn't consult military contractors about attacking Iran. The president may have had mixed motives, including bad ones -- such as the desire to be seen as a tough guy and war leader decades after evading the military draft -- but pleasing the “war industry" wasn't one of them.

While Eisenhower's remark long has been construed as scorn for military contractors, he actually acknowledged their necessity. He had been a general of the Army when the United States found itself badly unprepared for the world war into which it was dragged in December 1941.

On reflection Eisenhower said: “Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action. ... We can no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense. We have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. … This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. ... Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. ... In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex."

The “war industry" that Senator Murphy accuses of complicity in Trump's attack on Iran includes jet-engine manufacturer Pratt & Whitney in East Hartford and Middletown, for which 1st District U.S. Rep. John B. Larson is always cheerleading. It includes nuclear-submarine maker Electric Boat in Groton, for which 2nd District U.S. Rep. Joe Courtney spends much time supplicating. And it includes Sikorsky Aircraft in Stratford, whose fortunes are guarded by 3rd District U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro.

In turn, Pratt is a subsidiary of Raytheon, EB a subsidiary of General Dynamics, and Sikorsky a subsidiary of Lockheed-Martin, all giants of military contracting.

Yet Larson, Courtney and DeLauro, all Democrats like Murphy, quickly expressed opposition to Trump's attack on Iran. While they also voted against impeaching the president for the attack, their voting to impeach Trump for disregarding the War Powers Act when they had condoned similar violations by Democratic presidents might have seemed hypocritical.

Serious journalists might ask Murphy if his Democratic colleagues in Connecticut, so supportive of the military contractors in their districts, are tools of the ‘war industry" he thinks induced the president to attack Iran.

Eisenhower was right. As totalitarian nations pursue ever-more devastating weapons, the United States needs to keep ahead of them, even if this country doesn't need as many nuclear warheads as it has. Whether and how to use those weapons will always be a matter of judgment for elected officials.

By scapegoating military contractors to gain more approval on the far left, Murphy showed his lack of judgment and exceeded Trump's own posturing and demagoguery.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Crowd-sourcing Boston history

Boston’s State Street and the old State House in 1801.

Slightly edited text from The Boston Guardian

(Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s editor, is chairman of The Boston Guardian. He didn’t write this article.)

Local historian Jim Vrabel has a vision for a crowd sourced history of Boston that tells the whole story of the city.

His new website, WhenAndWhereInBoston.org, is a sweeping, searchable and explorable database of Boston history that Vrabel calls “an all Boston Wiki,” designed to gather, preserve and present the events, places and people who have shaped the city.

And no detail is too insignificant to be left out.

“Too often we just think that the history of Boston started and stopped with the Revolutionary War. Well, it didn’t,” Vrabel said in an interview. “So I decided to put all the material I had gathered into this website and invite other people to do so as well.”

The result is an open access platform that allows users to search, explore and contribute historical facts, each one vetted by a panel of local historians before being presented on the website as a straightforward paragraph accompanying a pin on a map and attributed to a source.

Vrabel previously worked as an historical author, a newspaper journalist and for 25 years in the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Services under the administrations of Mayors Raymond Flynn and Thomas Menino.

He said that the idea for the website grew from a realization that books alone no longer meet the needs of modern history seekers.

In modernity, much of the public’s casual consumption of history is now filtered through artificial intelligence assisted search engines, creating a version of history that is only as complete as our virtual documentation of it.

Contributions to WhenAndWhereInBoston already include overlooked histories like that of a United Service Organizations (USO) post, facilities that provided support and extracurriculars to U.S. servicemen, built on Boston Common in the 1940s that excluded Black service-members.

“Just before we launched, one of the people on the editorial committee, [Lynn Johnson], wrote an op-ed on a USO post that was built on Boston Common in the ‘40s that wasn’t very kind toward Black people,” Vrabel said. “I’d never heard of it and I’m sure most Bostonians never heard of it, and it was [history] in danger of being lost.”

Though the website currently reflects much of Vrabel’s professional historical encyclopedia, drawn from his previous works, including books When in Boston: A Timeline & Almanac and A People’s History of the New Boston, he hopes the project is only just beginning.

The site, which is run as a nonprofit, was built thanks to an anonymous donor. While Vrabel and his team are exploring long-term funding options, including potentially partnering with a nonprofit institution or local university, he is committed to keeping the platform free of advertising and focused solely on the facts.

The West End Museum hosted a kickoff event for the site and Vrabel hopes to build deeper partnerships with local institutions as the site grows. “They want to add West End history to it, just like very neighborhood wants to see themselves represented,” he said.

Recent federal funding cuts tied to the Trump administration's efforts to “restoring truth and sanity to American history,” have cut short the West End Museum’s efforts to research a lesser-known history of LGBTQ activism in the West End.

Vrabel’s vision for his website is simple, to create a place where Boston’s full story can be told. “History should be written by everybody, winners or losers,” he said. “If it happened, it’s history. So, this is the place to go to find it out, and to put it in.”

Alone together — table transitions

The way we live now— recent scene in a Providence eatery.

—Photo by William Morgan

“The Calling of St. Matthew,’’ by Caravaggio (1571-1610)