And cheap

“Available” (watercolor), byWilliam Talmadge Hall, in his series “Obstruction to a Landscape’’.

Where it’s wettest

Item Information

Title:

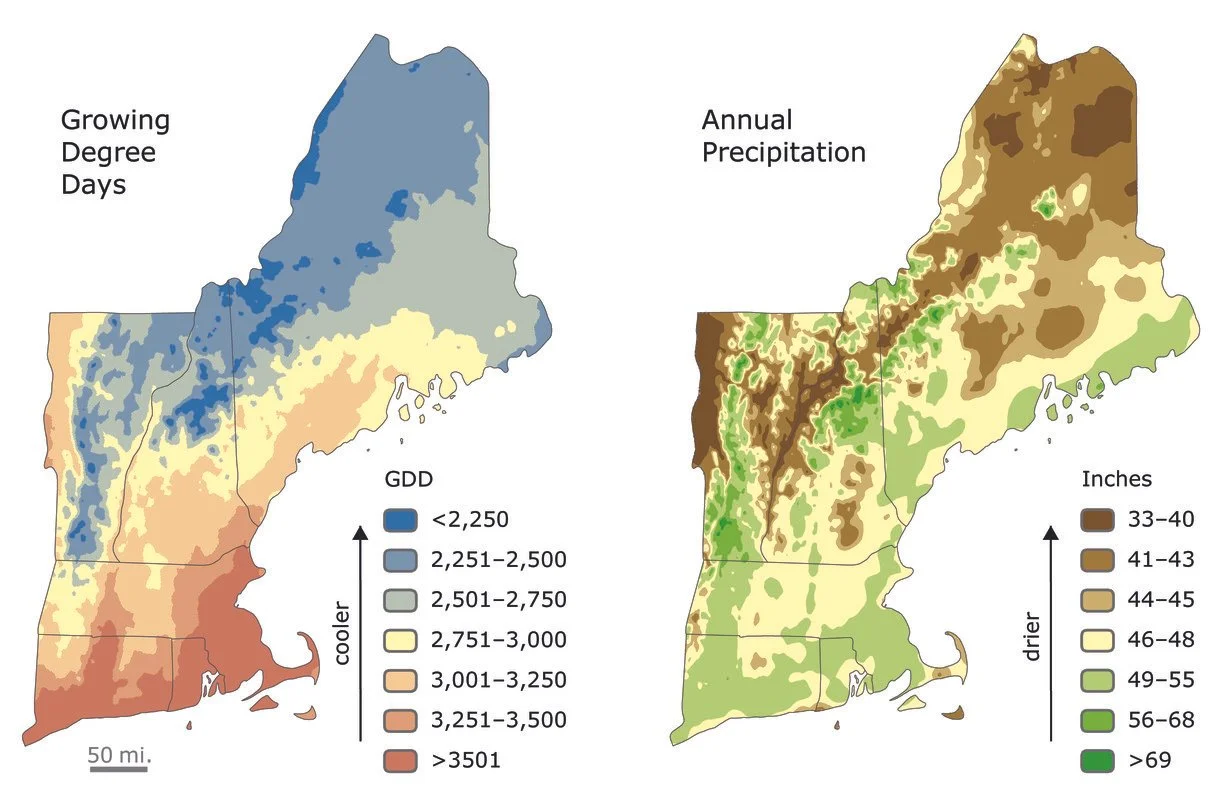

New England Climate Graph

Description:

2-10 Although precipitation and temperature (shown as growing degree days, a measure of total warmth over the year) broadly decline to the north in New England, those patterns are strongly modified by elevation.

Name on Item:

Brian R. Hall [Compiler]

Date:

February 26, 2016

Format:

Genre:

Location:

Harvard University

Harvard Forest Archives

Collection (local):

Harvard Forest Martha's Vineyard Collection

Subjects:

Coastal

Regional Studies

Climate

Places:

New England (area)

Permalink:

https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/vh53xs759

Terms of Use:

Copyright (c) Brian R. Hall

This work is licensed for use under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND).

Llewellyn King: You must manage rejection

“Pope Makes Love To Lady Mary Wortley Montagu,’’ by William Powell Frith,’’ depicts Lady Mary Wortley Montagu laughingly rejecting poet Alexander Pope's (1688-1744) pleas for courtship.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It is school commencement season. So I am taking the liberty of sharing my column of May 10, 2024, which was first published by InsideSources, and later published by newspapers across the country.

As so many commencement addresses haven’t been delivered yet this year, I thought I would share what I would have said to graduates if I had been invited by a college or university to be a speaker.

“The first thing to know is that you are graduating at a propitious time in human history — for example, think of how artificial intelligence is enabling medical breakthroughs.

“A vast world of possibilities awaits you because you are lucky enough to be living in a liberal democracy. It happens to be America, but the same could be true of any of the democratic countries.

“Look at the world, and you will see that the countries with democracy are also prosperous places where individuals can follow their passion. Doubly or triply so in America.

“Despite all the disputes, unfairness and politics, the United States is foremost among places to live and work — where the future is especially tempting. I say this having lived and worked on three continents and traveled to more than 180 countries. Just think of the tens of millions who would live here if they could.

“In a society that is politically and commercially free, as it is in the United States, the limits we encounter are the limits we place on ourselves.

“That is what I want to tell you: Don’t fence yourself in.

“But do work always to keep that freedom, your freedom, especially now.

“Seldom mentioned, but the greatest perverters of careers, stunters of ambition and all-around enfeeblers you will contend with aren’t the government, a foreign power, shortages or market conditions, but how you manage rejection.

“Fear of rejection is, I believe, the great inhibitor. It shapes lives, hinders careers and is ever-present, from young love to scientific creation.

“The creative is always vulnerable to the forces of no, to rejection.

“No matter what you do, at some point you will face rejection — in love, in business, in work or in your own family.

“But if you want to break out of the pack and leave a mark, you must face rejection over and over again.

“Those in the fine and performing arts and writers know rejection; it is an expected but nonetheless painful part of the tradition of their craft. If you plan to be an artist of some sort or a writer, prepare to face the dragon of rejection and fight it all the days of your career.

“All other creative people face rejection. Architects, engineers and scientists face it frequently. Many great entrepreneurial ideas have faced early rejection and near defeat.

“If you want to do something better, differently or disruptively, you will face rejection.

“To deal with this world where so many are ready to say no, you must know who you are. Remember that: Know who you are.

“But you can’t know who you are until you have found out who you are.

“Your view of yourself may change over time, but I adjure you always to judge yourself by your bests, your zeniths. That is who you are. Make past success your default setting in assessing your worth when you go forth to slay the dragons of rejection.

“There are two classes of people you will encounter again and again in your lives. The yes people and the no people.

“Seek out and cherish those who say yes. Anyone can say no. The people who have changed the world, who have made it a better place, are the people who have said, ‘Yes.’ ‘Why not?’ ‘Let’s try.’

“Those are people you need in life, and that is what you should aim to be: a yes person. Think of it historically: Thomas Edison, Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt, and Steve Jobs were all yes people, undaunted by frequent rejection.

“Try to be open to ideas, to different voices and to contrarian voices. That way, you will not only prosper in what you seek to do, but you will also become someone who, in turn, will help others succeed.

“You enter a world of great opportunities in the arts, sciences and technology but with attendant challenges. The obvious ones are climate, injustice, war and peace.

“Think of yourselves as engineers, working around those who reject you, building for others, and having a lot of fun doing it.

“Avoid being a no person. No is neither a building block for you nor for those who may look to you. Good luck!”

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Subscribe to Llewellyn King's File on Substack

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

And rise and fall

“Push and Pull” (acrylic on canvas), by Sam Chappell, at Portland Art Gallery, during this month.

She says:

“To me, the act of being in nature is inseparable from feeling. Every landscape has its own personality, which in turn can spark a different series of emotions. I rely on a play of colors and expressive brushstrokes in an attempt to relate the whole experience of a landscape, in the hopes that viewers can build their own relationships and emotional attachment to it.’’

Breaking up a log jam on the Penobscot River around the turn of the last century, when Maine was a world lumber and wood-pulp center.

He’ll now take your order

“Mr. Funny/Mr. Slap” (glass sculpture), by Peter Muller, based on a drawing by Israel Hicks, age eleven, at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum & Art Center.

The Brattleboro Retreat treats mental illness and drug addiction.

Chris Powell: Conn. devalues education while throwing more money at it

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Except to the teacher unions, Connecticut's Linda McMahon is a big relief as secretary of the U.S. Education Department, mainly because her predecessor, Connecticut's Miguel Cardona, was such a disaster.

Cardona spent most of his time pandering to the unions. In contrast, the other day McMahon celebrated National Charter Schools Week, applauding competition among schools and the reduction of union influence, which has dumbed down education while inflating its costs.

As long as the teacher unions have so much power in the Democratic Party, and are the foremost special-interest in politics in most states, as in Connecticut, there's no chance of saving public education, and alternative schools may be the only way of preserving any education at all.

Still, it would be nice if somebody tried to restore public education. For public education often used to accomplish what private education seldom could and usually didn't even try to do: integrate society comprehensively -- racially, ethnically, religiously, economically, and by all levels of student intelligence.

Of course, children would and will always be bratty, snobby, cruel, and cliquish much of the time, but even then public schools still can introduce them to different kinds of people and force them to deal with differences and thereby get a hint of the need to unify the country.

Regional “magnet’’ schools in Connecticut and elsewhere were meant to increase racial integration by putting city and suburban students together across municipal boundaries. But there aren't enough “magnet’’ schools to achieve much integration, and, as Hartford's experience has shown, the integration achieved by “magnet’’ schools has led to greater segregation of the urban underclass. For the "magnet" schools have drawn the more parented and engaged students out of neighborhood schools in the city, leaving the students in those schools even more indifferent and demoralized.

The urban underclass is the essence of the education problem. Many people naturally want to escape it and place their children in schools that aren't dragged down by their demographics. That means “magnet’’ or charter schools or, most of all, fleeing the city for the suburbs, not that all suburban schools are so much better.

The only way to recover the integrative influence of public education may be to try to improve public education everywhere at once, first by recognizing that student learning correlates far more with parenting than with school spending. Parenting has declined not just because welfare policy is so pernicious, subsidizing fatherlessness and child neglect, but also because government and schools have let parenting decline by eliminating behavioral and academic standards for both parents and students.

There are no penalties for parents who fail to see that their children get to school reliably. There are no penalties for parents who avoid contact with their children's teachers when something is wrong. There are no penalties for parents or students when students fail to learn.

Indeed, Connecticut's only comprehensive policy of public education -- social promotion -- destroys behavioral and academic standards. It proclaims to parents and students alike that there is no need to learn and that school isn't important. Thus Connecticut devalues education even while increasing its cost.

Connecticut's underclass has figured this out. The underclass knows that no student needs to earn a high school diploma, and that people who have children they are unprepared to support will be subsidized extensively by the government in a fatherless home -- subsidized enough to avoid starvation but not enough to get a proper upbringing.

But if even ignorant students must be graduated from high school, at least their dismal academic records could be printed on their diplomas so a diploma might mean something again, if only a horror story.

Making failing students repeat grades, as was done before self-esteem trumped learning, would have even more impact. Limiting students to two repeated grades before graduating them early but ignorant would have still more.

Until society forcefully demonstrates its respect for education and realizes that just throwing more money at it doesn't work, the underclass won't respect it either.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

African, but with ‘universal themes’

Senambele (Senufo) artist, N Ivory Coast, SW Burkina Faso, SW Mali, NW Ghana. Composite animal helmet mask (kponiougo), late 19th-early 20th Century, wood, pigment, in the ongoing show “Festival: A Celebration of African Art,’’ at the Fitchburg (Mass.) Art Museum.

The museum explains:

“Drawing upon universal themes of life, death, power, love, and celebration, the show presents highlights of the museum’s African art collection organized around the concepts of Masquerades, Ceremonial Life, Ritual Life and Domestic Life.’’

Central Fitchburg, including Nashua River, rail tracks and commuter rail station.

— Photo by Nick Allen

Amy Waxman: Experts say Trump regime has struck new blow against biosecurity by axing flu-virus-vaccine project

An illustration of the mechanism of action of a messenger RNA vaccine

Text from From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

The Trump administration’s cancellation of $766 million in contracts to develop mRNA vaccines against potential pandemic flu viruses is the latest blow to national defense, former health-security officials said. They warned that the U.S. could be at the mercy of other countries in the next pandemic.

“The administration’s actions are gutting our deterrence from biological threats,” said Beth Cameron, a senior adviser to the Brown University Pandemic Center and a former director at the White House National Security Council. “Canceling this investment is a signal that we are changing our posture on pandemic preparedness,” she added, “and that is not good for the American people.”

Flu pandemics killed up to 103 million people worldwide last century, researchers estimate.

In anticipation of the next big one, the U.S. government began bolstering the nation’s pandemic flu defenses during the George W. Bush administration. These strategies were designed by the security council and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority at the Department of Health and Human Services, among other agencies. The plans rely on rolling out vaccines rapidly in a pandemic. Moving fast hinges on producing vaccines domestically, ensuring their safety, and getting them into arms across the nation through the public health system.

The Trump administration is undermining each of these steps as it guts health agencies, cuts research and health budgets, and issues perplexing policy changes, health security experts said.

Since President Donald Trump took office, at least half of the security council’s staff have been laid off or left, and the future of BARDA is murky. The nation’s top vaccine adviser, Peter Marks, resigned under pressure in March, citing “the unprecedented assault on scientific truth.”

Most recently, Trump’s clawback of funds for mRNA vaccine development put Americans on shakier ground in the next pandemic. “When the need hits and we aren’t ready, no other country will come to our rescue and we will suffer greatly,” said Rick Bright, an immunologist and a former BARDA director.

Countries that produced their own vaccines in the covid-19 pandemic had first dibs on the shots. While the United States, home to Moderna and Pfizer, rolled out second doses of mRNA vaccines in 2021, hundreds of thousands of people in countries that didn’t manufacture vaccines died waiting for them.

The most pertinent pandemic threat today is the bird flu virus H5N1. Researchers around the world were alarmed when it began spreading among cattle in the U.S. last year. Cows are closer to humans biologically than birds, indicating that the virus had evolved to thrive in cells like our own.

As hundreds of herds and dozens of people were infected in the U.S., the Biden administration funded Moderna to develop bird flu vaccines using mRNA technology. As part of the agreement, the U.S. government stipulated it could purchase doses in advance of a pandemic. That no longer stands.

Researchers can make bird flu vaccines in other ways, but mRNA vaccines are developed much more quickly because they don’t rely on finicky biological processes, such as growing elements of vaccines in chicken eggs or cells kept alive in laboratory tanks.

Time matters because flu viruses mutate constantly, and vaccines work better when they match whatever variant is circulating.

Developing vaccines within eggs or cells can take 10 months after the genetic sequence of a variant is known, Bright said. And relying on eggs presents an additional risk when it comes to bird flu because a pandemic could wipe out billions of chickens, crashing egg supplies.

Decades-old methods that rely on inactivated flu viruses are riskier for researchers and time-consuming. Still the Trump administration invested $500 million into this approach, which was largely abandoned by the 1980s after it caused seizures in children.

“This politicized regression is baffling,” Bright said.

A bird flu pandemic may begin quietly in the U.S. if the virus evolves to spread between people but no one is tested at first. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s dashboard suggests that only 10 farmworkers have been tested for the bird flu since March. Because of their close contact with cattle and poultry, farmworkers are at highest risk of infection.

As with many diseases, only a fraction of people with the bird flu become severely sick. So the first sign that the virus is widespread might be a surge in hospital cases.

“We’d need to immediately make vaccines,” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan.

The U.S. government could scale up production of existing bird flu vaccines developed in eggs or cells. However, these vaccines target an older strain of H5N1 and their efficacy against the virus circulating now is unknown.

In addition to the months it takes to develop an updated version within eggs or cells, Rasmussen questioned the ability of the government to rapidly test and license updated shots, with a quarter of HHS staff gone. If the Senate approves Trump’s proposed budget, the agency faces about $32 billion in cuts.

Further, the Trump administration’s cuts to biomedical research and its push to slash grant money for overhead costs could undermine academic hospitals, rendering them unable to conduct large clinical trials. And its cuts to the CDC and to public health funds to states mean that fewer health officials will be available in an emergency.

“You can’t just turn this all back on,” Rasmussen said. “The longer it takes to respond, the more people die.”

Researchers suggest other countries would produce bird flu vaccines first. “The U.S. may be on the receiving end like India was, where everyone — rich people, too — got vaccines late,” said Achal Prabhala, a public health researcher in India at medicines access group AccessIBSA.

He sits on the board of a World Health Organization initiative to improve access to mRNA vaccines in the next pandemic. A member of the initiative, the company Sinergium Biotech in Argentina, is testing an mRNA vaccine against the bird flu. If it works, Sinergium will share the intellectual property behind the vaccine with about a dozen other groups in the program from middle-income countries so they can produce it.

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, an international partnership headquartered in Norway, is providing funds to research groups developing rapid-response vaccine technology, including mRNA, in South Korea, Singapore, and France. And CEPI committed up to $20 million to efforts to prepare for a bird flu pandemic. This year, the Indian government issued a call for grant applications to develop mRNA vaccines for the bird flu, warning it “poses a grave public health risk.”

Pharmaceutical companies are investing in mRNA vaccines for the bird flu as well. However, Prabhala says private capital isn’t sufficient to bring early-stage vaccines through clinical trials and large-scale manufacturing. That’s because there’s no market for bird flu vaccines until a pandemic hits.

Limited supplies means the United States would have to wait in line for mRNA vaccines made abroad. States and cities may compete against one another for deals with outside governments and companies, like they did for medical equipment at the peak of the covid pandemic.

“I fear we will once again see the kind of hunger games we saw in 2020,” Cameron said.

In an email response to queries, HHS communications director Andrew Nixon said, “We concluded that continued investment in Moderna’s H5N1 mRNA vaccine was not scientifically or ethically justifiable.” He added, “The decision reflects broader concerns about the use of mRNA platforms—particularly in light of mounting evidence of adverse events associated with COVID-19 mRNA vaccines.”

Nixon did not back up the claim by citing analyses published in scientific journals.

In dozens of published studies, researchers have found that mRNA vaccines against covid are safe. For example, a placebo-controlled trial of more than 30,000 people in the U.S. found that adverse effects of Moderna’s vaccine were rare and transient, whereas 30 participants in the placebo group suffered severe cases of covid and one died.

More recently, a study revealed that three of nearly 20,000 people who got Moderna’s vaccines and booster had significant adverse effects related to the vaccine, which resolved within a few months. Covid, on the other hand, killed four people during the course of the study.

As for concerns about the heart issue, myocarditis, a study of 2.5 million people who got at least one dose of Pfizer’s mRNA vaccine revealed about 2 cases per 100,000 people. Covid causes 10 to 105 myocarditis cases per 100,000.

Nonetheless, HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who founded an anti-vaccine organization, has falsely called covid shots “the deadliest vaccine ever made.” And without providing evidence, he said the 1918 flu pandemic “came from vaccine research.”

Politicized mistrust in vaccines has grown. Far more Republicans said they trust Kennedy to provide reliable information on vaccines than their local health department or the CDC in a recent KFF poll: 73% versus about half.

Should the bird flu become a pandemic in the next few years, Rasmussen said, “we will be screwed on multiple levels.”

Amy Waxman is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter

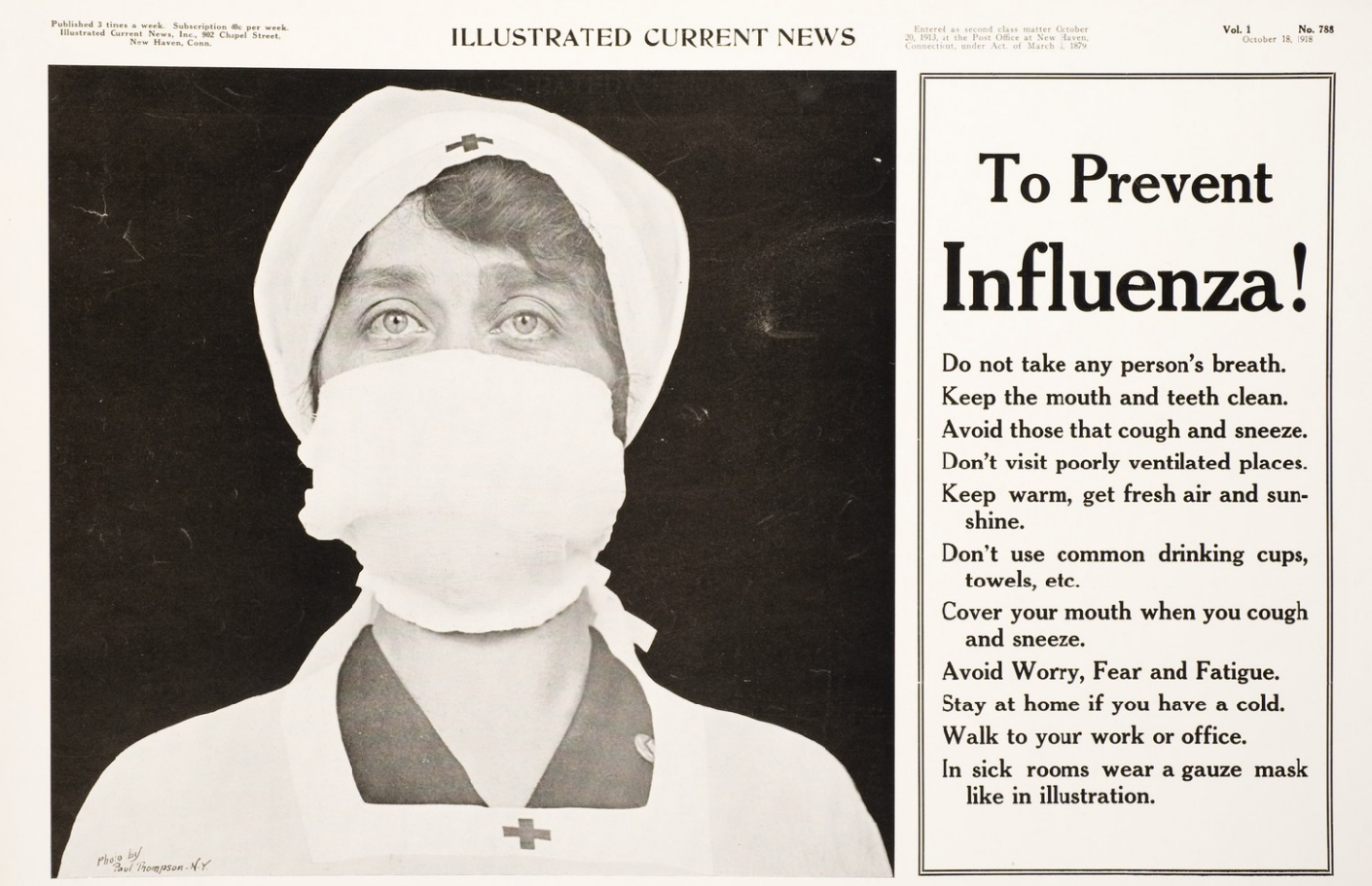

Advice during the 1918-1920 “Spanish” flu pademic, which may have killed up to 100 million people.

‘For the service of the weak’

First British attack in the Battle of Bunker Hill, June 17, 1775.

Array of American forces for the battle.

Herewith speech by then Massachusetts Lt. Gov. Calvin Coolidge on June 17, 1918, Bunker Hill Day, at the Roxbury Historical Society. He went on to become governor, U.S. vice president and president.

Reverence is the measure not of others but of ourselves. This assemblage on the one hundred and forty-third anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill tells not only of the spirit of that day but of the spirit of to-day. What men worship that will they become. The heroes and holidays of a people which fascinate their soul reveal what they hold are the realities of life and mark out a line beyond which they will not retreat, but at which they will stand to overcome or die. They who reverence Bunker Hill will fight there. Your true patriot sees home and hearthstone in the welfare of his country.

Rightly viewed, then, this day is set apart for an examination of ourselves by recounting the deeds of the men of long ago. What was there in the events of the seventeenth day of June, 1775, which holds the veneration of Americans and the increasing admiration of the world? There are the physical facts not too unimportant to be unworthy of reiteration even in the learned presence of an Historical Society. A detachment of men clad for the most part in the dress of their daily occupations, standing with bared heads and muskets grounded muzzle down in the twilight glow on Cambridge Common, heard Samuel Langdon, President of Harvard College, seek divine blessing on their cause and marched away in the darkness to a little eminence at Charlestown, where, ere the setting of another sun, much history was to be made and much glory lost and won. When a new dawn had lifted the mists of the Bay, the British, under General Howe, saw an intrenchment on Breed’s Hill, which must be taken or Boston abandoned. The works were exposed in the rear to attack from land and sea. This was disdained by the king’s soldiers in their contempt for the supposed fighting ability of the Americans. Leisurely, as on dress parade, they assembled for an assault that they thought was to be a demonstration of the uselessness of any armed resistance on the part of the Colonies. In splendid array they advanced late in the day. A few straggling shots and all was still behind the parapet. It was easier than they had expected. But when they reached a point where ‘t is said the men behind the intrenchments could see the whites of their eyes, they were met by a withering fire that tore their ranks asunder and sent them back in disorder, utterly routed by their despised foes. In time they form and advance again but the result is the same.

The demonstration of superiority was not a success. For a third time they form, not now for dress parade, but for a hazardous assault. This time the result was different. The patriots had lost nothing of courage or determination but there was left scarcely one round of powder. They had no bayonets. Pouring in their last volley and still resisting with clubbed muskets, they retired slowly and in order from the field. So great was the British loss that there was no pursuit. The intensity of the battle is told by the loss of the Americans, out of about fifteen hundred engaged, of nearly twenty per cent, and of the British, out of some thirty-five hundred engaged, of nearly thirty-three per cent, all in one and one half hours.

It was the story of brave men bravely led but insufficiently equipped. Their leader, Colonel Prescott, had walked the breastworks to show his men that the cannonade was not particularly dangerous. John Stark, bringing his company, in which were his Irish compatriots, across Charlestown Neck under the guns of the battleships, refused to quicken his step. His Major, Andrew McCleary, fell at the rail fence which he had held during the day. Dr. Joseph Warren, your own son of Roxbury, fell in the retreat, but the Americans, though picking off his officers, spared General Howe. They had fought the French under his brother.

Such were some of the outstanding deeds of the day. But these were the deeds of men and the deeds of men always have an inward significance. In distant Philadelphia, on this very day, the Continental Congress had chosen as the Commander of their Army, General George Washington, a man whose clear vision looked into the realities of things and did not falter. On his way to the front four days later, dispatches reached him of the battle. He revealed the meaning of the day with one question, “Did the militia fight?” Learning how those heroic men fought, he said, “Then the liberties of the Country are safe.” No greater commentary has ever been made on the significance of Bunker Hill.

We read events by what goes before and after. We think of Bunker Hill as the first real battle for independence, the prelude to the Revolution. Yet these were both afterthoughts. Independence Day was still more than a year away and then eight years from accomplishment. The Revolution cannot be said to have become established until the adoption of the Federal Constitution. No, on this June day, these were not the conscious objects sought. They were contending for the liberties of the country, they were not yet bent on establishing a new nation nor on recognizing that relationship between men which the modern world calls democracy. They were maintaining well their traditions, these sons of Londonderry, lovers of freedom and anxious for the fray, and these sons of the Puritans, whom Macaulay tells us humbly abased themselves in the dust before the Lord, but hesitated not to set their foot upon the neck of their king.

It is the moral quality of the day that abides. It was the purpose of those plain garbed men behind the parapet that told whether they were savages bent on plunder, living under the law of the jungle, or sons of the morning bearing the light of civilization. The glorious revolution of 1688 was fading from memory. The English Government of that day rested upon privilege and corruption at the base, surmounted by a king bent on despotism, but fortunately too weak to accomplish any design either of good or ill. An empire still outwardly sound was rotting at the core. The privilege which had found Great Britain so complacent sought to establish itself over the Colonies. The purpose of the patriots was resistance to tyranny. Pitt and Burke and Lord Camden in England recognized this, and, loving liberty, approved the course of the Colonies. The Tories here, loving privilege, approved the course of the Royal Government. Bunker Hill meant that the Colonies would save themselves and saving themselves save the mother country for liberty. The war was not inevitable. Perhaps wars are never inevitable. But the conflict between freedom and privilege was inevitable. That it broke out in America rather than in England was accidental.

Liberty, the rights of man against tyranny, the rights of kings, was in the air. One side must give way. There might have been a peaceful settlement by timely concessions such as the Reform Bill of England some fifty years later, or the Japanese reforms of our own times, but wanting that a collision was inevitable. Lacking a Bunker Hill there had been another Dunbar.

The eighteenth century was the era of the development of political rights. It was the culmination of the ideas of the Renaissance. It was the putting into practice in government of the answer to the long pondered and much discussed question, “What is right?” Custom was giving way at last to reason. Class and caste and place, all the distinctions based on appearance and accident were giving way before reality. Men turned from distinctions which were temporal to those which were eternal. The sovereignty of kings and the nobility of peers was swallowed up in the sovereignty and nobility of all men. The inequal in quantity became equal in quality.

The successful solution of this problem was the crowning glory of a century and a half of America. It established for all time how men ought to act toward each other in the governmental relation. The rule of the people had begun.

Bunker Hill had a deeper significance. It was an example of the great law of human progress and civilization. There has been much talk in recent years of the survival of the fittest and of efficiency. We are beginning to hear of the development of the super-man and the claim that he has of right dominion over the rest of his inferiors on earth. This philosophy denies the doctrine of equality and holds that government is not based on consent but on compulsion. It holds that the weak must serve the strong, which is the law of slavery, it applies the law of the animal world to mankind and puts science above morals. This sounds the call to the jungle. It is not an advance to the morning but a retreat to night. It is not the light of human reason but the darkness of the wisdom of the serpent.

The law of progress and civilization is not the law of the jungle. It is not an earthly law, it is a divine law. It does not mean the survival of the fittest, it means the sacrifice of the fittest. Any mother will give her life for her child. Men put the women and children in the lifeboats before they themselves will leave the sinking ship. John Hampden and Nathan Hale did not survive, nor did Lincoln, but Benedict Arnold did. The example above all others takes us back to Jerusalem some nineteen hundred years ago. The men of Bunker Hill were true disciples of civilization, because they were willing to sacrifice themselves to resist the evils and redeem the liberties of the British Empire. The proud shaft which rises over their battlefield and the bronze form of Joseph Warren in your square are not monuments to expediency or success, they are monuments to righteousness.

This is the age-old story. Men are reading it again to-day — written in blood. The Prussian military despotism has abandoned the law of civilization for the law of barbarism. We could approve and join in the scramble to the jungle, or we could resist and sacrifice ourselves to save an erring nation. Not being beasts, but men, we choose the sacrifice.

This brings us to the part that America is taking at the end of its second hundred and fifty years of existence. Is it not a part of that increasing purpose which the poet, the seer, tells us runs through the ages? Has not our Nation been raised up and strengthened, trained and prepared, to meet the great sacrifice that must be made now to save the world from despotism? We have heard much of our lack of preparation. We have been altogether lacking in preparation in a strict military sense. We had no vast forces of artillery or infantry, no large stores of munitions, few trained men. But let us not forget to pay proper respect to the preparation we did have, which was the result of long training and careful teaching. We had a mental, a moral, a spiritual training that fitted us equally with any other people to engage in this great contest which after all is a contest of ideas as well as of arms. We must never neglect the military preparation again, but we may as well recognize that we have had a preparation without which arms in our hands would very much resemble in purpose those now arrayed against us.

Are we not realizing a noble destiny? The great Admiral who discovered America bore the significant name of Christopher. It has been pointed out that this name means Christ-bearer. Were not the men who stood at Bunker Hill bearing light to the world by their sacrifices? Are not the men of to-day, the entire Nation of to-day, living in accordance with the significance of that name, and by their service and sacrifice redeeming mankind from the forces that make for everlasting destruction? We seek no territory and no rewards. We give but do not take. We seek for a victory of our ideas. Our arms are but the means. America follows no such delusion as a place in the sun for the strong by the destruction of the weak. America seeks rather, by giving of her strength for the service of the weak, a place in eternity.

We’re all a bunch

“Quartet,’’ by Kathryn Geismar, in the group show “Selfhood,’’ at the Danforth Art Museum, Framingham, Mass., though June.

She says:

“My work explores the complex and often fragmentary nature of identity through portraits and abstract collage. My recent figurative series depicts adolescents ranging in age from 14-21. These young adults are claiming an identity in an age when binary definitions of self are under question….Figures move in and out of focus; layers of mylar promote looking through; grommets pierce through layers like jewelry and at other times like windows into layers below.’’

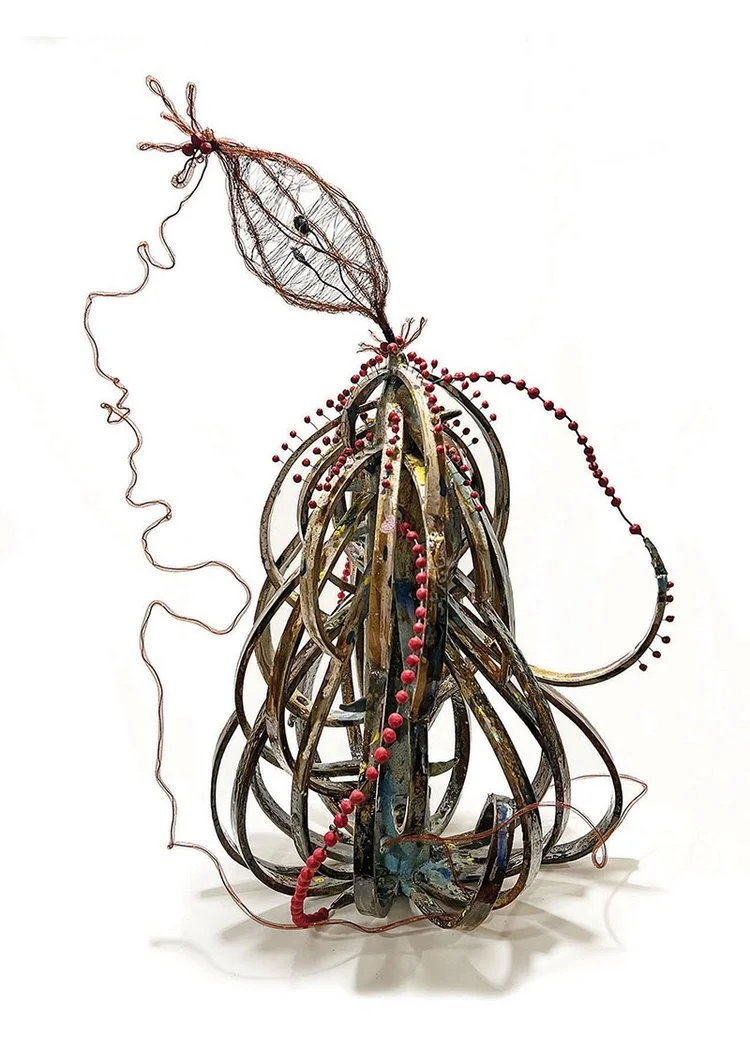

In life’s tangled web

Work by Jongeun Gina Lee in her show “Shift,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston through June 29.

From her artist’s statement:

“I imagine each piece I make is on its own journey, just like everything in Nature transforms in lineage of time and space. I decenter myself and find peace accepting I am a tiny part of a larger cycle. It allows me to cope with turbulences and disappointments in life. I observe resilience and balance in precarious journeys of all existence in nature, while all suffers from the vulnerability and randomness of existence…. The current body of works represents slow incubation of inner strength, cautious hope and resilience with optimism in life. The empty but charged space using linear elements articulates the hidden energy in nature which transforms and pushes everything through its journey. The assembly of linear units in my forms is a metaphor of paradoxical adaptability in time and space.’’

Elic Weitzel: The rise, fall and rise of white-tailed deer

A white-tailed deer

From The Conversation (except for image above):

Elic Weitzel is Peter Buck P0stdoctoral Research Fellow at the Smithsonian Institution.

Elic Weitzel received funding from the National Science Foundation (award #2128707) to support this research.

Given their abundance in American backyards, gardens and highway corridors these days, it may be surprising to learn that white-tailed deer were nearly extinct about a century ago. While they currently number somewhere in the range of 30 million to 35 million, at the turn of the 20th Century, there were as few as 300,000 whitetails across the entire continent: just 1% of the current population.

This near-disappearance of deer was much discussed at the time. In 1854, Henry David Thoreau had written that no deer had been hunted near Concord, Massachusetts, for a generation. In his famous “Walden,” he reported that:

“One man still preserves the horns of the last deer that was killed in this vicinity, and another has told me the particulars of the hunt in which his uncle was engaged. The hunters were formerly a numerous and merry crew here.”

But what happened to white-tailed deer? What drove them nearly to extinction, and then what brought them back from the brink?

As a historical ecologist and environmental archaeologist, I have made it my job to answer these questions. Over the past decade, I’ve studied white-tailed deer bones from archaeological sites across the eastern United States, as well as historical records and ecological data, to help piece together the story of this species.

Precolonial rise of deer populations

White-tailed deer have been hunted from the earliest migrations of people into North America, over 15,000 years ago. The species was far from the most important food resource at that time, though.

Archaeological evidence suggests that white-tailed deer abundance only began to increase after the extinction of megafauna species like mammoths and mastodons opened up ecological niches for deer to fill. Deer bones become very common in archaeological sites from about 6,000 years ago onward, reflecting the economic and cultural importance of the species for Indigenous peoples.

A 16th-Century engraving of Indigenous Floridians hunting deer while disguised in deerskins. Theodor de Bry/DEA Picture Library/De Agostini via Getty Images

Despite being so frequently hunted, deer populations do not seem to have appreciably declined due to Indigenous hunting prior to AD 1600. Unlike elk or sturgeon, whose numbers were reduced by Indigenous hunters and fishers, white-tailed deer seem to have been resilient to human predation. While archaeologists have found some evidence for human-caused declines in certain parts of North America, other cases are more ambiguous, and deer certainly remained abundant throughout the past several millennia.

Human use of fire could partly explain why white-tailed deer may have been resilient to hunting. Indigenous peoples across North America have long used controlled burning to promote ecosystem health, disturbing old vegetation to promote new growth. Deer love this sort of successional vegetation for food and cover, and thus thrive in previously burned habitats. Indigenous people may have therefore facilitated deer population growth, counteracting any harmful hunting pressure.

More research is needed, but even though some hunting pressure is evident, the general picture from the precolonial era is that deer seem to have been doing just fine for thousands of years. Ecologists estimate that there were roughly 30 million white-tailed deer in North America on the eve of European colonization – about the same number as today.

Elic Weitzel and volunteers excavate for deer bones at a 17th-century colonial site in Connecticut. Scott Brady

Colonial-era fall of deer numbers

To better understand how deer populations changed in the colonial era, I recently analyzed deer bones from two archaeological sites in what is now Connecticut. My analysis suggests that hunting pressure on white-tailed deer increased almost as soon as European colonists arrived.

At one site dated to the 11th to 14th centuries – before European colonization – I found that only about 7% to 10% of the deer killed were juveniles.

Hunters generally don’t take juvenile deer if they’re frequently encountering adults, since adult deer tend to be larger, offering more meat and bigger hides.

Additionally, hunting increases mortality on a deer herd but doesn’t directly affect fertility, so deer populations experiencing hunting pressure end up with juvenile-skewed age structures. For these reasons, this low percentage of juvenile deer prior to European colonization indicates minimal hunting pressure on local herds.

However, at a nearby site occupied during the 17th century – just after European colonization – between 22% and 31% of the deer hunted were juveniles, suggesting a substantial increase in hunting pressure.

Researchers can tell from the size and development of a deer’s bones its stage of life.

This elevated hunting pressure likely resulted from the transformation of deer into a commodity for the first time. Venison, antlers and deerskins may have long been exchanged within Indigenous trade networks, but things changed drastically in the 17th century. European colonists integrated North America into a trans-Atlantic mercantile capitalist economic system with no precedent in Indigenous society. This applied new pressures to the continent’s natural resources.

Deer – particularly their skins – were commodified and sold in markets in the colonies initially and, by the 18th century, in Europe as well. Deer were now being exploited by traders, merchants and manufacturers desiring profit, not simply hunters desiring meat or leather. It was the resulting hunting pressure that drove the species toward its extinction.

20th-century rebound of white-tailed deer

Thanks to the rise of the conservation movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, white-tailed deer survived their brush with extinction.

Concerned citizens and outdoorsmen feared for the fate of deer and other wildlife, and pushed for new legislative protections.

The Lacey Act of 1900, for example, banned interstate transport of poached game and – in combination with state-level protections – helped end commercial deer hunting by effectively de-commodifying the species. Aided by conservation-oriented hunting practices and reintroductions of deer from surviving populations to areas where they had been extirpated, white-tailed deer rebounded.

The story of white-tailed deer underscores an important fact: Humans are not inherently damaging to the environment. Hunting from the 17th through 19th centuries threatened the existence of white-tailed deer, but precolonial Indigenous hunting and environmental management appear to have been relatively sustainable, and modern regulatory governance in the 20th Century forestalled and reversed their looming extinction.

Sticky stuff

Pine cones releasing pollen.

“Now I know that summer is here, no matter how cold it is at night, for when I went out to the car this morning, the windshield was dusted with orange and the whole shiny dark blue of the body was powdered. The pine pollen has come! This is a thick, almost oily deposit that penetrates everything. If you close a room and lock the windows, the sills will be drifted with the pollen the next morning. The floors turn orange.’’

Gladys Taber, in My Own Cape Cod (1971)

Our ‘bitch-goddess’

“The moral flabbiness born of the exclusive worship of the bitch-goddess SUCCESS. That - with the squalid cash interpretation put on the word “success” -- is our national disease.’’

―William James (1842-1910), philosopher, psychologist and Harvard professor, in a 1906 letter to English writer H.G. Wells (1866-1946).

How does brain create its reality?

“Preponderance of Beech” (oil on linen), by Don Collins, in his show “Understory,’’ at AVA Gallery and Art Center, Lebanon, N.H., through June 28.

He says in his Web site:

“I am fascinated by the experience of encountering art, both for myself and for others. Contemporary brain science, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), gives tantalizing hints about how a brain creates its reality. I am interested in what that process means to an artist, the viewer and the creative experience that hangs between them.’’

Planting an urban mini-forest

Text below excerpted from ecoRI News

“PROVIDENCE — There was a method to the madness of planting 185 trees and 80 shrubs 2 to 3 feet apart in a 1,000-square-foot corner of the Pearl Street Garden.

“The method is named after Akira Miyawaki, a Japanese botanist and ecologist who specialized in natural vegetation restoration of degraded land. His method has been implemented worldwide. He died in 2021 at the age of 93.

“The Miyawaki Method focuses on swiftly creating dense, biodiverse forests — or, in the case of the Pearl Street Garden, a microforest — using native vegetation. The practice involves planting seedlings at high density, to mimic natural forest ecosystems and to rely on natural processes such as competition and mutualism to accelerate growth….”

But they keep all their clothes on

“Summer, New England” (1912 oil on canvas), by Maurice Prendergast (1858-1924), American painter

Through the mountains

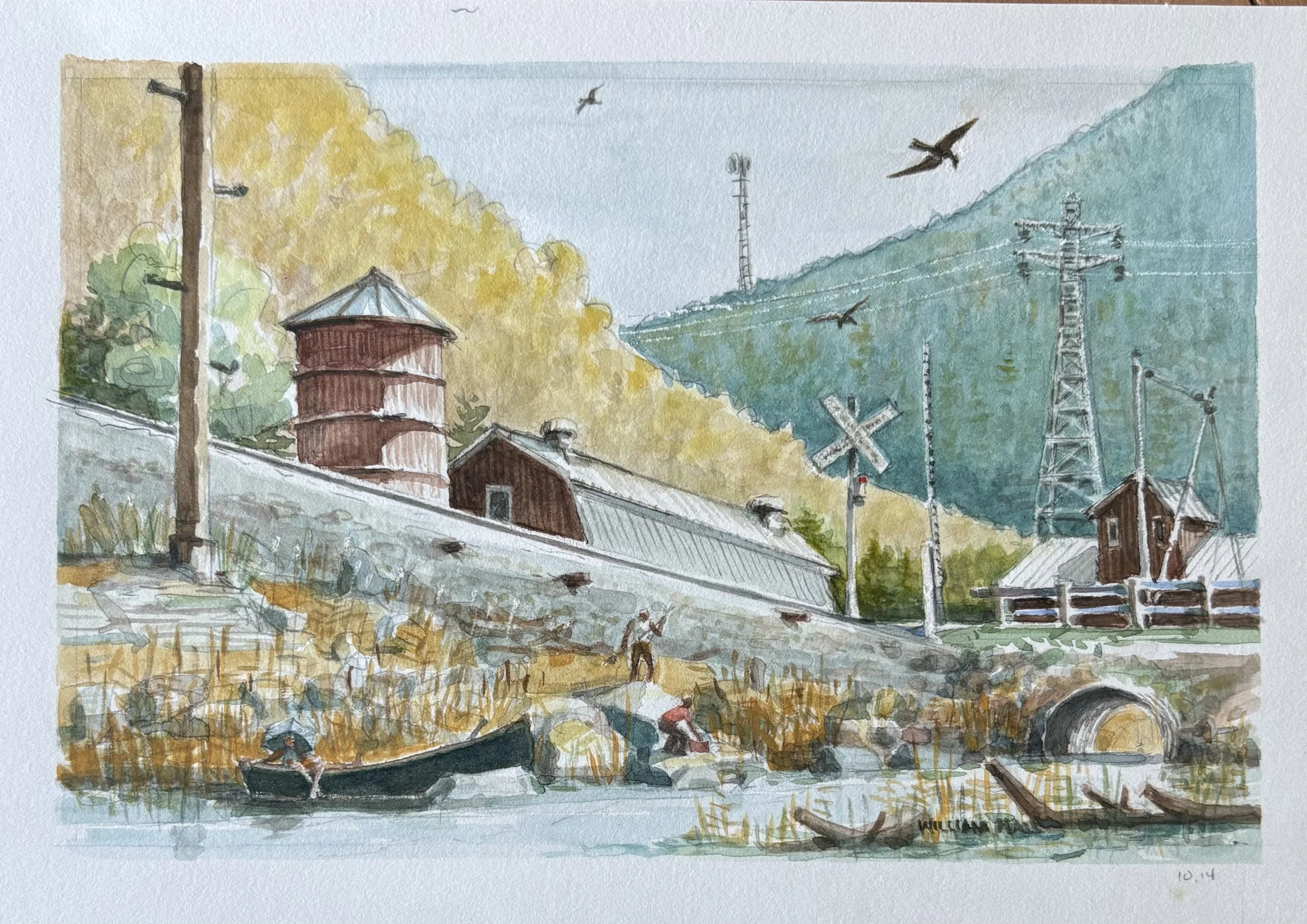

“RR Crossing in a Valley” (watercolor), by William Talmadge Hall, in his “Obstruction to a Landscape’’ series. He’s based in Rhode Island and Florida but spent his early years in Vermont.

Llewellyn King: Harnessing power in new ways

The falls at such dams on New England rivers were used to power the region’s textile and other mills.

Northfield Mountain, in Northfield, Mass., FirstLight’s flagship facility, is New England’s largest energy-storage operation This giant water battery is capable of powering more than 1 million homes for up to 7.5 hours each day.

This article first appeared on Forbes.com

Virginia is the first state to formally press for the creation of a virtual power plant. Glenn Youngkin, the state’s Republican governor, signed the Community Energy Act on May 2, which mandates Dominion Energy to launch a 450-megawatt virtual power plant (VPP) pilot program.

Virginia isn’t alone in this endeavor, but it is certainly the most out front. There are many incipient VPPs clustered around utilities across the country.

A virtual power plant is the ultimate realization of something that has been going on for a long time as utilities have been hooking up various power sources, managed conservation and underused generation, known as distributed energy resources (DER). These, according to even small utilities, can contribute up to and possibly over 10 percent electricity to a utility system.

Organized and formalized and with enough coverage, DER becomes a VPP. Sometimes the terms are used interchangeably.

A virtual power plant not only depends on managed conservation and underused generation but also on some imaginative use of resources, like hooking up transportation fleets to discharge their batteries onto the grid when they aren’t in use. Electric school buses are frequently cited as playing a role in future VPPs. Conservation and solar roofs with related batteries are the backbone of DER and VPPs. Eventually, they are expected to be common to most utilities or consortia of utilities.

In Owings Mills, Md., an engineer and inventor with a slew of patents to his name, Key Han, dreams of a different kind of VPP, one which could, if widely deployed, provide a new source of baseload power.

Han, CEO and chief scientist at DDMotion, has pioneered speed-converter technology which, if widely deployed, would produce inexpensive, reliable energy in sufficient quantity to be described as baseload. Indeed, he said in an interview, “It would be a huge new source of baseload.”

Han’s technology converts variable energy inputs into constant speed outputs. For example, the flow of water in a stream is variable but with his speed-converter technology, the energy in the flow can be captured and converted to a constant speed output.

With his technology, grid-quality frequency can flow from many sources without extensive civil engineering or major construction, he told me. In particular, Han cited power dams, like the ones in New England which were built in the 19th Century to drive the textile mills.

“A simple harnessing module with a generator behind the spillway coupled with my technology can produce frequency that is constant and ready to go on the grid. If you have enough of these simple, low-cost generators installed, you have created a new baseload source, a virtual power plant of a different and exceptionally reliable kind,” Han said.

Another use of the same DDMotion technology would remedy what is becoming a growing problem for wind and solar generators: the lack of rotating inertia. Inertia is essential for utility operators to fix sudden changes in frequency caused by changes in generation or consumption (50 cycles in Europe and 60 cycles in the United States).

Lack of inertia has been blamed for the widespread blackout on the Iberian Peninsula and is becoming an issue for utilities with a lot of solar and wind generation, so called inverter power. This refers to the grooming with an inverter to power to grid-quality alternating current from its original direct current.

Here, again, his technology can inexpensively resolve the inertia problem for wind and solar generation, Han said. Either using a mechanical system or an electronic one, wind and solar systems could provide rotating inertia.

Increasingly, utilities are looking for untapped sources of power which can be bundled together into VPPs.

Renew Home, a Google-financed company, claims 3 gigawatts of electricity savings, which it says makes it the leader in VPPs. It relies on managing end-use load primarily in homes with load shedding of high energy-consuming devices during peaks. This is accomplished by using special thermostats and smart meters.

Industry experts believe artificial intelligence will be a key to extracting the most energy out of unconventional sources as well as fine tuning usage.

VPPs are here and many more are coming.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Subscribe to Llewellyn King's File on Substack

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.