William Morgan: Sensing the soul of winter

The search for New England postcards recently produced this scene of a snowed-in village from a bin in the Red Chair shop in Hudson, N.Y. The Red Chair specializes in French antiques, linens, glassware and silver. But this undramatic townscape curiously appeared amidst a box of slightly naughty belle époque cards.

In the Red Chair

— Photo by William Morgan

This could be any town in northern New England, back when we had more major snowfalls than we do now. The giveaway that it might be farther north is the church, clearly not your wooden white Congregational meeting house, and so my guess was northern, francophone Maine. There was no legend on the back side, just a cryptic identification in pencil: “Canada’’.

The picture that this postcard evoked for me was the opening image in a slide presentation by the brilliant Canadian architect Peter Rose. He was one of three noted designers invited to interview at the Speed Museum, a limited competition to see who might to chosen to craft a master plan for the Louisville art museum. The other two were Robert Venturi, the guru of Post Modernism, and his opposite, the neo-Corbusian “white” architect, Charles Gwathmey. Both the rumpled Philadelphian and the super-slick New Yorker spoke about their work, that is, mostly themselves. The Montreal native showed several pictures of his native city and the Quebec landscape blanketed in snow.

Rose, who gave up a spot on the Canadian Olympic ski team to go to Yale’s architecture school, described how a downhill racer has to read the snow, “experiencing and understanding space and materials – snow, ice and trees, effects of light and contour–while hurtling through space as fast as possible.” Buildings, too, Rose noted, are experienced through motion as well; successfully reading topography, he declared, played an important part in his role as a designer.

Peter Rose in a private house in Manhattan in 2008.

—Photo by William Morgan

As Rose spoke of suns low in the sky and ice-covered farms and streets, one of the members of the Speed selection committee whispered to me that he did not understand why the talk of winter. While Rose prevailed over his more famous competitors in Louisville, that misunderstanding of the quiet yet passionate soul of America’s northern neighbor was sadly typical.

Providence-based writer William Morgan has written a number of books that deal with architecture in northern climes, including Snowbound: Dwelling in Winter and Peter Rose: Houses.

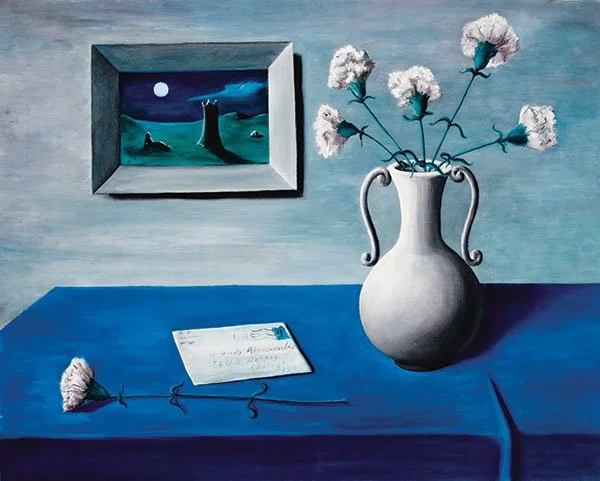

Too scared to open it?

“Letter from Karl”(1940) (oil on canvas), by Gertrude Abercrombie (1909-1977), in the show “Gertrude Abercrombie: The Whole World Is a Mystery,’’ at the Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, through Jan. 1, 2026.

The curator says:

The show is the first nationally touring presentation of Abercrombie’s art, celebrating “an artist who has been historically marginalized. Abercrombie (1909–1977) was a critical figure in the mid-20th Century Chicago art and jazz scenes. Though she had a singular vision, her reliance on her inner consciousness and use of a fantastical style connected her to broader developments in American Modernism.’’

Honoring a musical pioneer

Lowell Mason

Lowell Mason House, in Medfield, Mass.

This is an edited version of a press release

MEDFIELD, Mass.

Following years of historic-house restoration and national fundraising campaigns, the birthplace of one of America’s most influential musical figures will soon be transformed into a space for music education in Medfield. The plan is for it to open in 2027.

Lowell Mason (1792-1872) was responsible for introducing music as a subject to be taught in public schools at a time when this was unheard of. Mason famously said: “Children should be taught music as they are taught to read.” He paid from his own funds for the first-year trial program in Boston schools in 1836, and when this became a great success, other schools followed suit.

Mason also composed and arranged thousands of popular hymns, including “Joy to the World" and “Nearer My God to Thee,’’ as well as publishing many of America’s earliest hymn books and musical instruction manuals.

In 2011, Mason’s birthplace was saved from being razed by the concerned citizens of Medfield. The Lowell Mason House foundation was formed, and the house was moved nearby in Medfield and preserved to become a public place for music-making and musical education. This effort is now close to being accomplished, with multiple practice rooms, a library and the acquisition of the last Mason and Hamlin grand piano made under Mason family ownership all coming together.

“This has become a labor of love not only for local residents but also for those affiliated with music education advocacy at the state and national levels,” says Thomas Reynolds, executive director of the Lowell Mason House.

“We are now embarking upon the Lowell Mason House ‘Fund-to-the-Finish’ campaign with the goal of opening the center to the public in 2027. We encourage all those who love music and value music education for children and adults to visit the Lowell Mason House website to learn more and to consider supporting our final push to completion.”

The Lowell Mason House foundation is excited to be working this summer in an advisory capacity with a class that is a part of the Boston University Arts Administration Graduate Program. The class will be researching potential individual and corporate/foundation prospects as well as advising on the Lowell Mason House fundraising plan.

“In working together, we hope to help the leadership of the Lowell Mason House advance its fundraising efforts and demonstrate to students the opportunities and challenges experienced by nonprofit leaders in raising funds,” says Mary Doorley-Simboski, an ACFRE (Advanced Certified Fund Raising Executive) and faculty member conducting the class.

The board of the Lowell Mason House is eager to receive input from Ms. Doorley-Simboski and her class. “Small volunteer non-profits, such as ours, do not have the resources to hire a staff of professionals, so the opportunity to have a group of people passionate about arts and arts administration to assist us with this effort is fantastic,” says Reynolds.

This summer has been particularly important for the Lowell Mason House as another unique opportunity has presented itself to the group. A direct descendent of Lowell Mason, Will Mason, currently an associate professor of music at Wheaton College, in Norton, Mass., will be taking a new position as associate professor of music at Skidmore College, in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. Professor Mason contacted us because he owns the Mason Family piano and is willing to part with it.

This grand piano was manufactured by Mason & Hamlin in 1929 while under family ownership and made for Henry Mason, Lowell Mason’s grandson. Mason family friends Sergei Rachmaninoff, a famous Russian composer, conductor and pianist, and French composer Maurice Ravel were both huge advocates of Mason & Hamlin pianos, specifically requesting them when planning solo performances.

“The opportunity to acquire the Mason Family piano at this time, adding it to our collection of Lowell Mason handwritten music and other personal items, is incredibly timely as we make our final fundraising push,” says Reynolds.

Information about the Lowell Mason House and its “Fund-to-the-Finish” campaign can be found at this link.

A tune from Mason's Handbook for the Boston Academy of Music.

Moonstruck

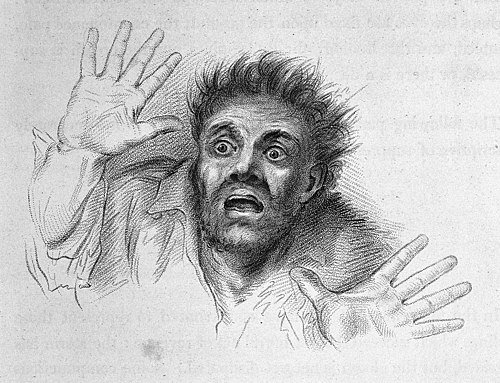

“Mito de luz de luna (Moonlight Myth)’’ (oil on canvas), by Carlos Almaraz (1941-1989), in the group show “The Body Imagined,’’ at the Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury, Conn., through Sept. 28.

The museum says the show “offers a unique lens on how the human figure has been depicted, reimagined, and transformed across generations and artistic movements.’’

Elisabeth Rosenthal: Despite ‘No Surprises Act,’ surprise medical bills show up to dismay patients

Except for picture above, from Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

Last year in Massachusetts, after finding lumps in her breast, Jessica Chen went to Lowell General Hospital-Saints Campus, part of Tufts Medicine, for a mammogram and sonogram. Before the screenings, she asked the hospital for the estimated patient responsibility for the bill using her insurance, Tufts Health Plan. Her portion, she was told, would be $359 — and she paid it. She was more than a little surprised weeks later to receive a bill asking her to pay an additional $1,677.51. “I was already trying to stomach $359, and this was many times higher,” Chen, a physician assistant, told me.

The No Surprises Act, which took effect in 2022, was rightly heralded as a landmark piece of legislation, which “protects people covered under group and individual health plans from receiving surprise medical bills,” according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. And yet bills that take patients like Chen by surprise just keep coming.

With the help of her software-wise boyfriend, she found the complicated “machine-readable” master price list that hospitals are required to post online and looked up the negotiated rate between Lowell General and her insurer. It was $302.56 — less than she had paid out-of-pocket.

CMS is charged with enforcing the law, so Chen sent a complaint about the surprising bill to the agency. She received a terse email in return: “We have reviewed your complaint and have determined that the rights and protections of the No Surprises Act do not apply.”

When I asked the health system to explain how such a surprising off-estimate bill could be generated, Tufts Medicine spokesperson Jeremy Lechan responded by email: “Healthcare billing is complex and includes various factors and data points, so actual charges for care provided may differ from initial estimates. We understand the frustration these discrepancies can cause.”

Here’s the problem: While the No Surprises Act has been a phenomenal success in taking on some unfair practices in the wild West of medical billing, it was hardly a panacea.

In fact, the measure protected patients primarily from only one particularly egregious type of surprise bill that had become increasingly common before the law’s enactment: When patients unknowingly got out-of-network care at an in-network facility, or when they had no choice but to get out-of-network care in an emergency. In either case, before President Donald Trump signed the law late in his first term, patients could be hit with tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars in out-of-network bills that their insurance wouldn’t pay.

The No Surprises Act also provided some protection from above-estimate bills, but at the moment, the protection is only for uninsured and self-pay patients, so it wouldn’t apply in Chen’s case since she was using health insurance.

But patients who do qualify generally are entitled to an up-front, good-faith estimate for treatment they schedule at least three business days in advance or if they request one. Patients can dispute a bill if it is more than $400 over the estimate. (The No Surprises Act also required what amounted to a good-faith estimate of out-of-pocket costs for patients with insurance, but that provision has not been implemented, since, nearly five years later, the government still has not issued rules about exactly what form it should take.)

So, surprising medical bills — bills that the patient could not have anticipated and never consented to — are still stunning countless Americans.

Jessica Robbins, who works in product development in Chicago, was certainly surprised when, out of the blue, she was recently billed $3,300 by Endeavor Health for a breast MRI she had received two years earlier, with prior authorization from her then-insurer, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois. In trying to resolve the problem, she found herself caught in a Kafkaesque circle involving dozens of calls and emails. The clinic where she had the procedure no longer existed, having been bought by Endeavor. And she no longer had Blue Cross.

“We are actively working with the patient and their insurer to resolve this matter,” Endeavor spokesperson Allie Burke said in an emailed response to my questions.

Mary Ann Bonita of Fresno, California, was starting school this year to become a nursing assistant when, on a Friday, she received a positive skin test for tuberculosis. Her school’s administration said she couldn’t return to class until she had a negative chest X-ray. When her doctor from Kaiser Permanente didn’t answer requests to order the test for several days, Bonita went to an emergency room and paid $595 up front for the X-ray, which showed no TB. So she and her husband were surprised to receive another bill, for $1,039, a month later, “with no explanation of what it was for,” said Joel Pickford, Bonita’s husband.

In the cases above, each patient questioned an expensive, unexpected medical charge that came as a shock — only to find that the No Surprises Act didn’t apply.

“There are many billing problems out there that are surprising but are not technically surprise bills,” Zack Cooper, an associate professor of economics at Yale University, told me. The No Surprises Act fixed a specific kind of charge, he said, “and that’s great. But, of course, we need to address others.”

Cooper’s research has found that before the No Surprises Act was passed, more than 25% of emergency room visits yielded a surprise out-of-network bill.

CMS’s official No Surprises Help Desk has received tens of thousands of complaints, which it investigates, said Catherine Howden, a CMS spokesperson. “While some billing practices, such as delayed bills, are not currently regulated” by the No Surprises Act, Howden said, complaint trends nonetheless help “inform potential areas for future improvements.” And they are needed.

Michelle Rodio, a teacher in Lakewood, Ohio, had a lingering cough weeks after a bout of pneumonia that required treatment with a course of antibiotics. She went to Cleveland Clinic’s Lakewood Family Health Center for an examination. Her X-ray was fine. As was her nasal swab — except for the stunning $2,700 bill it generated.

“I said, ‘This is a surprise bill!’” Rodio recalled telling the provider’s finance office. The agent said it was not.

“So I said, ‘Next time I’ll be sure to ask the doctor for an estimate when I get a nose swab.’”

“The doctors wouldn’t know that,” the agent replied, as Rodio recalled — and indeed physicians generally have no idea how much the tests they order will cost. And in any case, Rodio was not legally entitled to a binding estimate, since the part of the No Surprises Act that grants patients with insurance that right has not been implemented yet.

So she was stuck with a bill of $471 (the patient responsibility portion of the $2,700 charge) that she couldn’t have consented to (or rejected) in advance. It was surprising — shocking to her, even — but not a “surprise bill,” according to the current law. But shouldn’t it be?

Elisabeth Rosenthal is a reporter at Kaiser Family Foundation Health News.

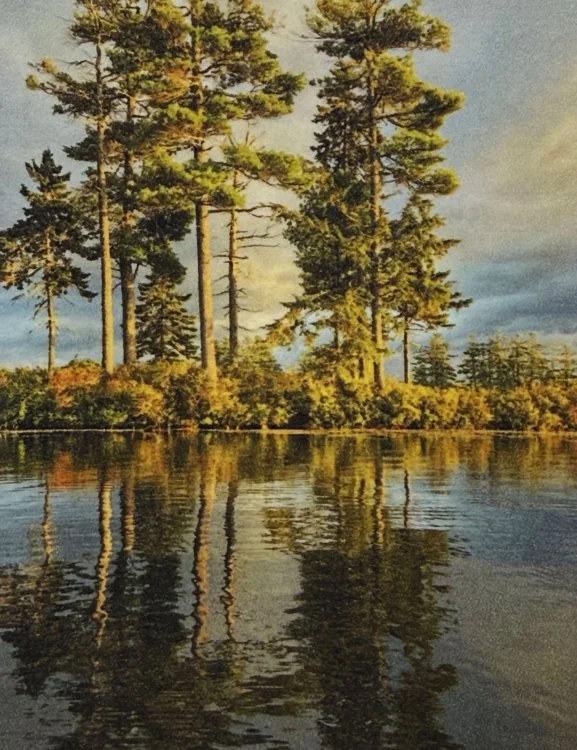

‘The mirror we are in’

“September Light,’’ by Susan Lirakis, in her show “Past and Future Memory,’’ at AVA Gallery and Art Center, Lebanon, N.H., through Aug 9.

The gallery says:

“Susan Lirakis elevates ordinary moments with a sense of reverence. She presents her photographic images using various techniques, including gelatin silver prints, cyanotypes, pigment prints, and some adorned with gold or silver leafing…. Several images incorporate a mirror in the camera, allowing us to look forward while simultaneously reflecting backward, capturing a sense of being in the present moment. Does this dual perspective change our view of the present or how we perceive time? Does it illustrate how the past influences our understanding of the present and our outlook on the future? The use of blurred and interpretive imagery prompts us to contemplate the kind of mirror we are in this context.’’

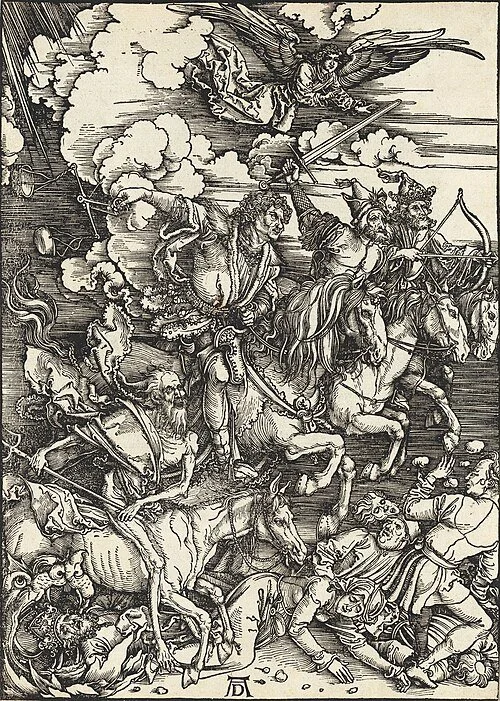

Chris Powell: Does Trump’s budget doom Conn.?

“Four Horsemen of The Apocalypse” (woodcut print), by Albrecht Dürer (1461-1529)

MANCHESTER, Conn.

According to Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont, the federal budget just enacted by the Republican majority in Congress and President Trump is nearly the end of the world.

The governor says the budget will have “devastating impact on millions of Americans for years to come and was passed for the sole purpose of giving tax cuts to millionaires and billionaires. It will amount to a massive income transfer from the poorest and most vulnerable Americans to the wealthiest."

But Dan Haar of the Hearst Connecticut newspapers reports that, by quadrupling to $40,000 the federal income tax deductibility of state and local taxes -- the “SALT" deduction, which Democratic leaders in Connecticut and other high-tax states long have supported -- the new budget will substantially reduce federal income taxes for hundreds of thousands of middle- and upper-middle class Connecticut households.

As for the “massive income transfer from the poorest and most vulnerable Americans to the wealthiest," the poor don't pay federal income taxes, nor, in Connecticut, state income taxes. The “income" for the poor about which the governor is worried is actually what in a less politically correct era was called welfare.

The governor says the new budget will “bankrupt" the federal government by running a deficit in the trillions of dollars, requiring borrowing to cover the gap. But the federal government has long run huge deficits under Democratic administrations as well, which never bothered Democrats in Connecticut. Besides, since the government can create money out of nothing, it can never go bankrupt; it can only continue to devalue the dollar -- something else that has never bothered Connecticut Democrats.

The new budget, the governor says, “slashes critical safety-net programs, particularly Medicaid and SNAP" -- food subsidies -- "that so many hard-working American families need for their health and survival."

Yet in recent days there have been reports from all around the country about massive fraud in the Medicaid, Medicare, and SNAP programs -- some involving providers in Connecticut.

Indeed, a few months ago the governor's own public health and social services commissioner retired after it was disclosed that she had countenanced the termination of an audit of Medicaid fraud in which the governor's former deputy budget director and a former Democratic state representative have been indicted and a Bristol doctor has pleaded guilty.

Just the other week state prosecutors charged an acupuncturist from Milford with defrauding Medicaid of $123,000.

All this fraud doesn't mean that the Republican administration in Washington or the Democratic administration in Connecticut will be competent and determined enough to substantially reduce fraud in Medicaid, Medicare and food subsidies. But maybe a reduction in those appropriations is necessary to provide some incentive to look harder.

“With a federal administration insistent on eliminating critical safety nets," the governor said, “it is going to be nearly impossible for any state to backfill the billions in federal cuts we are going to face. … We will be meeting with our colleagues in the General Assembly to discuss next steps."

Those next steps may be interesting.

Will the federal cuts in Medicaid and food subsidies be so compelling as to cause the governor and legislators to cancel any of the grants they grandly announce practically every week for all sorts of inessential projects around the state?

Will the cuts be so compelling as to cause the governor to reconsider the blank check his administration has issued for illegal immigration?

Will the cuts be so compelling as to cause the governor to reconsider the pledge he made to the state employee unions in April? “Every year that I've been here you've gotten a raise," he told the unions, “and every year I'm here, you're going to get a raise."

Raises despite the cuts in the safety net? Despite natural disasters? Despite plague? Despite nuclear war?

Or will the cuts prompt the governor to call the legislature into special session, proclaim that state government simply can't economize, and propose to raise taxes going into an election year?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Llewellyn King: How crowdfunding brought a new wind technology to market

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

A California company, Wind Harvest, is in high gear to change the dynamics of wind energy and to vastly improve the economics of wind farms.

But the company wouldn’t be marketing to large energy users and wind farm operators today if it hadn’t used crowdfunding for its recent rounds of financing. Crowdfunding can get a startup over the hill.

Kevin Wolf, Wind Harvest co-founder and CEO, explained that developers of hardware face a double problem when it comes to financing: The banks won’t finance their customers’ projects until the technology has been certified and, in Wind Harvest’s case, dozens of their unique wind turbines have been operating for at least a year which requires money.

Wolf said, “It takes about two years to complete a ‘technology readiness level,’ unless a company is well-funded. Six months to have all the components arrive, six months to a year to install and fully test the prototype, and then another six months to complete the new design.” Meantime, a team of engineers and the bills have to be paid.

Venture capitalists have shown a decided disinclination to finance hardware, preferring computer-related software products, he said.

But with crowdfunding, often through a special-purpose company, thousands of individuals have become venture capitalists in companies like Wind Harvest. Many of those investors have hit it big.

Two standout companies which grew into multi-billion dollar ones: Oculus VR and Peloton.

Oculus, the virtual-reality technology company, used crowdfunding to raise $250,000 in 2012. Two years later, it was acquired by Facebook for $2 billion.

Peloton, the fitness company, started with crowdfunding of $307,000, achieved a valuation of $8.1 billion its initial public offering, and rose to astronomically high valuations during the Covid pandemic. It has now fallen back considerably, after many difficulties in the fitness industry.

Wind Harvest is essentially offering new infrastructure which, should it catch on, would give it a steady and fairly predictable path forward as both a wind turbine Original Equipment Manufacturer and as a renewable energy project developer.

The company’s product, trademarked as Wind Harvester, is a vertical-axis wind turbine (VAWT): The drive shaft and the electrical generator are aligned vertical to the ground. In traditional wind turbines, those components are horizontal to the ground.

The most famous vertical-axis wind turbine is the Darrieus, named after a French engineer who patented it in 1926. It has an elegant, eggbeater shape almost like a fine outdoor sculpture. But it ran into problems with vibration and other technical drawbacks and wasn’t a commercial success.

At the outset of the 1973-1974 energy crisis, in 1973, Sandia National Laboratory in New Mexico, one of the jewels in the crown of the national laboratory system, did considerable theoretical work on wind turbines, concentrating on vertical-axis designs. But when the research was moved to another laboratory, the horizontal-axis wind turbine (HAWT) became the focus.

The codes developed at Sandia are foundational to the Wind Harvest design. Wolf explained that the choice between VAWTs and HAWTs isn’t an either-or choice, except where wind shears are high and wind near the ground slows down. Then tall, horizontal-axis wind turbines have the advantage.

Wind Harvest turbines are designed to capture the wind on ridgelines, hills and mountain passes where wind funnels and accelerates turbines under the tall horizontal-axis turbines. VAWTs can take advantage of the powerful wind that swirls around near the ground. This turbulent wind at the surface is an unused resource now.

With the bottom of their blades between 25 feet and 50 feet off the ground and installed in pairs 3 feet apart from each, Wind Harvest turbines can double the output of electricity from a wind farm while still leaving enough clearance for agriculture, whether it is grazing animals or growing crops. So, add efficiency to the virtues of these turbines: better use of the wind resources, land and infrastructure.

Thanks to crowdfunding in four tranches, Wind Harvest is now ready to go to market with utility scale installations.

Wolf listed these additional virtues for VAWTs:

They can be entirely made in America. Right now their blades are extruded by Step-G in Germany.

They are designed to withstand the 180 mph wind gusts from a Category 5 hurricane.

Because they are short, they can use larger permanent magnet generators (PMGs) not made of rare earth magnets. For example, their PMGs can use ferrite magnets which are iron-based.

Wind Harvest installations have a fatigue life of 75 years with maintenance and periodic refurbishment. Most turbines now in use must be replaced after about 25 years.

The first Wind Harvesters to be put into service are planned for a dredge-spoil-created peninsula on St. Croix, the largest of the U.S. Virgin Islands, in the Caribbean Sea. The entire output of the first phase of the project will be bought by the oil refinery adjacent to the project site and replace the burning of costly propane for generation.

Big ideas now have funding sources besides “Shark Tank,” venture capital and the banks.

On X: @llewellynking2

Bluesky: @llewellynking.bsky.social

Subscribe to Llewellyn King's File on Substack

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island.

Plant Kingdom

“A Prickly Situation” (archival chromagenic pigment print), by Bob Stegmaier, in the group show “Flora,’’ at the Arts League of Lowell, through Sept. 7.

—Image courtesy of the Arts League of Lowell.

The curator explains:

The exhibition features the works of 45 artists, “shining a light on all types of flora. There is no end to how artists can interpret and depict the natural world. Some, like Bob Stegmaier, use photography and specific printing techniques to create interesting compositions, while others like Mary Hart and her sculptural piece “Flourish" (mixed recycled board and materials) take a more abstract and interpretive approach.’’

Looking back can be dangerous

‘‘the shape of memory’’ (installation image), by Carlie Trosclair, at the Maine Center for Contemporary Art, Rockland. through Sept. 7.

—Photo by Dave Clough

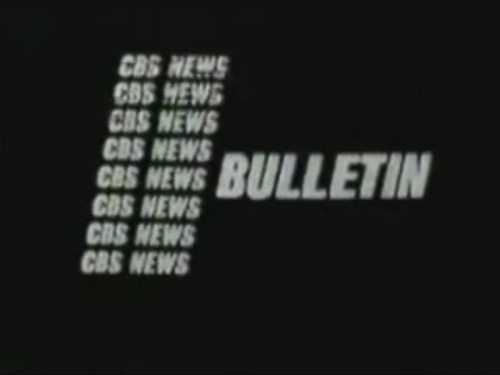

Michael J. Socolow: Will networks let autocratic Trump become their editor?

Michael J. Socolow is a professor of communication and journalism at the University of Maine.

His father, Sanford Socolow, worked for CBS News from 1956 to 1988.

ORONO, Maine

It was a surrender widely foreseen. For months, rumors abounded that Paramount would eventually settle the seemingly frivolous lawsuit brought by President Trump concerning editorial decisions in the production of a CBS interview with Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris in 2024.

On July 2, 2025, those rumors proved true: The settlement between Paramount and Trump’s legal team resulted in CBS’s parent company agreeing to pay $16 million to the future Donald Trump Library – the $16 million included Trump’s legal fees – in exchange for ending the lawsuit. Despite the opinion of many media law scholars and practicing attorneys who considered the lawsuit meritless, Shari Redstone, the largest shareholder of Paramount, yielded to Trump.

Redstone had been trying to sell Paramount to Skydance Media since July 2024, but the transaction was delayed by issues involving government approval.

Specifically, when the second Trump administration assumed power, on Jan. 20 2025, the new Federal Communications Commission had no legal obligation to facilitate, without scrutiny, the transfer of the CBS network’s broadcast licenses for its owned-and-operated TV stations to new ownership.

The FCC, under newly installed Republican Chairman Brendan Carr, was fully aware of the issues in the legal conflict between Trump and CBS at the time Paramount needed FCC approval for the license transfers. Without a settlement, the Paramount-Skydance deal remained in jeopardy.

Until it wasn’t.

At that point, Paramount joined Disney in implicitly apologizing for journalism produced by their TV news divisions.

Earlier in 2025, Disney had settled a different Trump lawsuit with ABC News in exchange for a $15 million donation to the future Trump Library. That lawsuit involved a dispute over the wording of the actions for which Trump was found liable in a civil lawsuit brought by E. Jean Carroll.

GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump said the CBS interview with Democratic nominee Kamala Harris was ‘‘fraudulent interference with an election.’’

It’s not certain what the ABC and CBS settlements portend, but many are predicting they will produce a “chilling effect” within the network news divisions. Such an outcome would arise from fear of new litigation, and it would install a form of internal self-censorship that would influence network journalists when deciding whether the pursuit of investigative stories involving the Trump administration would be worth the risk.

Trump has apparently succeeded where earlier presidents failed.

Presidential pressure

From Jimmy Carter trying to get CBS anchor Walter Cronkite to stop ending his evening newscasts with the number of days American hostages were being held in Iran to Richard Nixon’s administration threatening the broadcast licenses of The Washington Post’s TV stations to weaken Watergate reporting, previous presidents sought to apply editorial pressure on broadcast journalists.

But in the cases of Carter and Nixon, it didn’t work. The broadcast networks’ focus on both Watergate and the Iran hostage crisis remained unrelenting.

Nor were Nixon and Carter the first presidents seeking to influence, and possibly control, network news.

President Lyndon Johnson, who owned local TV and radio stations in Austin, Texas, regularly complained to his old friend, CBS President Frank Stanton, about what he perceived as biased TV coverage. Johnson was so furious with the CBS and NBC reporting from Vietnam, he once argued that their newscasts seemed “controlled by the Vietcong.”

Yet none of these earlier presidents won millions from the corporations that aired ethical news reporting in the public interest.

Before Trump, these conflicts mostly occurred backstage and informally, allowing the broadcasters to sidestep the damage to their credibility should any surrender to White House administrations be made public. In a “Reporter’s Notebook” on the CBS Evening News the night of the Trump settlement, anchor John Dickerson summarized the new dilemma succinctly: “Can you hold power to account when you’ve paid it millions? Can an audience trust you when it thinks you’ve traded away that trust?”

“The audience will decide that,” Dickerson continued, concluding: “Our job is to show up to honor what we witness on behalf of the people we witness it for.”

During the Iran hostage crisis, CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite ended every broadcast with the number of days the hostages had been held captive.

Holding power to account

There’s an adage in TV news: “You’re only as good as your last show.”

Soon, Skydance Media will assume control over the Paramount properties, and the new CBS will be on the airwaves.

When the licenses for KCBS in Los Angeles, WCBS in New York and the other CBS-owned-and-operated stations are transferred, we’ll learn the long-term legacy of corporate capitulation. But for now, it remains too early to judge tomorrow’s newscasts.

As a scholar of broadcast journalism and a former broadcast journalist, I recommend evaluating programs like 60 Minutes and the CBS Evening News on the record they will compile over the next three years – and the record they compiled over the past 50. The same goes for ABC World News Tonight and other ABC News programs.

A major complicating factor for the Paramount-Skydance deal was the fact that 60 Minutes has, over the past six months, broken major scoops embarrassing to the Trump administration, which led to additional scrutiny by its corporate ownership. Judged by its reporting in the first half of 2025, 60 Minutes has upheld its record of critical and independent reporting in the public interest.

If audience members want to see ethical, independent and professional broadcast journalism that holds power to account, then it’s the audience’s responsibility to tune it in. The only way to learn the consequences of these settlements is by watching future programming rather than dismissing it beforehand.

The journalists working at ABC News and CBS News understand the legacy of their organizations, and they are also aware of how their owners have cast suspicion on the news divisions’ professionalism and credibility. As Dickerson asserted, they plan to “show up” regardless of the stain, and I’d bet they’re more motivated to redeem their reputations than we expect.

I don’t think that reporters, editors and producers plan to let Donald Trump become their editor-in-chief over the next three years. But we’ll only know by watching.

New England’s only lizard

Juvenile Five-Lined Skink

Excerpted from an article by Frank Carini in ecoRI News in his series on threatened New England wildlife

“The five-lined skink is the only lizard found in New England, even though there are about 5,000 different species of lizards worldwide, according to the Connecticut Department of Energy & Environmental Protection….’’

“The small size and fragmented nature of skink populations leaves them vulnerable to ecological catastrophes, according to state officials. It’s listed as a threatened animal in Connecticut.

“The range of this species corresponds closely with the eastern deciduous forest. The Five-Lined Skink is found in southwestern New England — currently, parts of Vermont and Connecticut and historically in Massachusetts — south to northern Florida, west to Wisconsin, and in eastern Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. The species is at its northeastern range limit in southwestern New England.’’

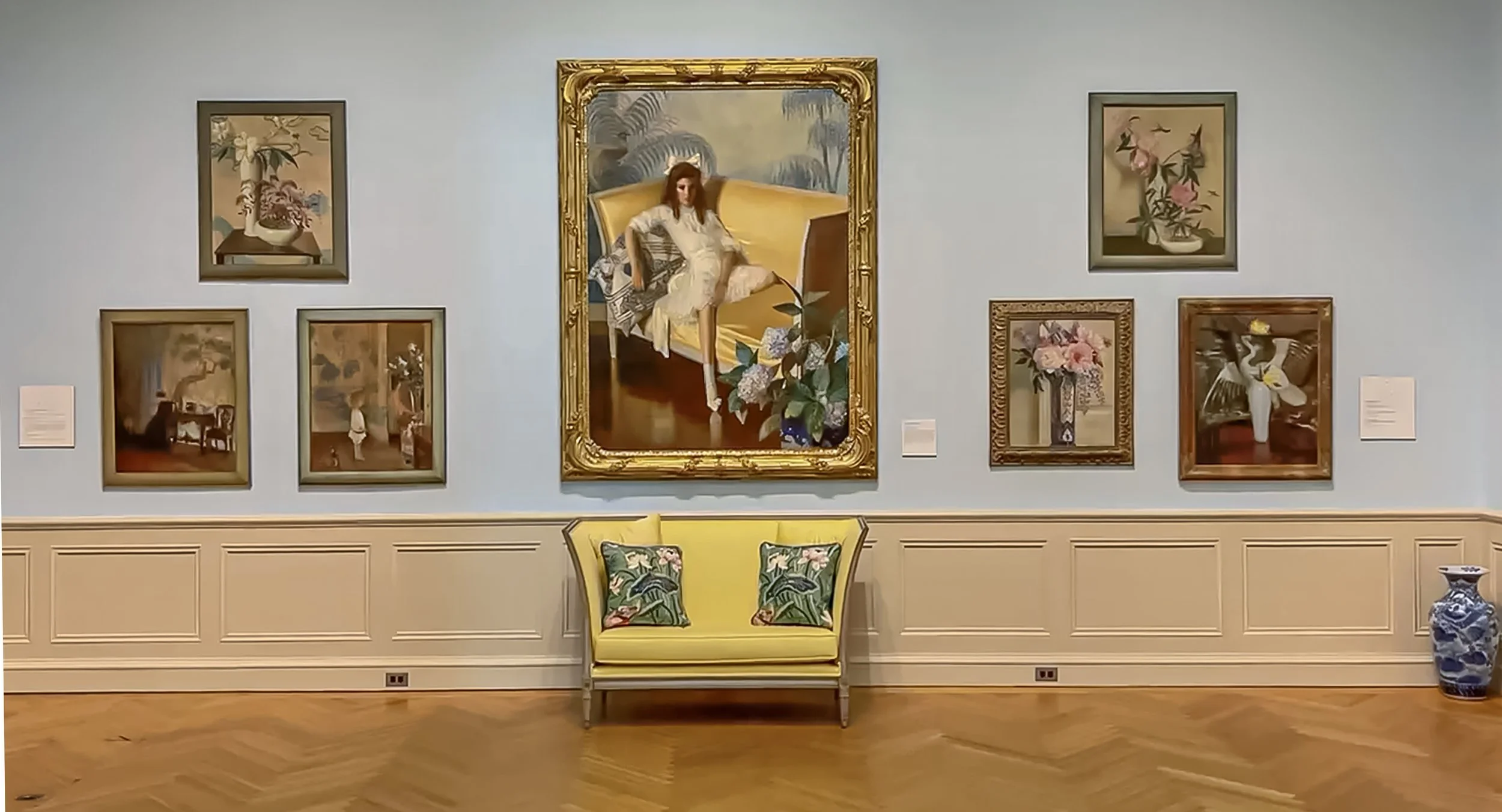

A visionary Gilded Age artist

Above, “Fantasy Landscape (Study for the Whitney Studio Mural,” circa 1911 (0il on canvas), by Howard Gardiner Cushing (1869-1916), in the show “Howard Gardiner Cushing: A Harmony of Line and Color,’’ at the Newport Art Museum, through Dec. 31

— From Private Collection

Below, installation view

— Photos by Sandy Nesbitt

The museum says:

“Curated by Ricardo Mercado and organized in Collaboration with Newport Curates, the show is a landmark exhibition celebrating the life and work of Howard Gardiner Cushing, a dynamic force in American art at the turn of the 20th Century. The exhibition is the first major retrospective in decades of one of the Gilded Age’s most visionary — and overlooked artists.’’

Whither the status of the historic Boston Fish Pier?

(New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian’s board but doesn’t write for the paper.)

A revived petition to grant landmark status to the Boston Fish Pier, at 212-234 Northern Avenue, is sparking debate among city officials, preservationists and business stakeholders.

As part of an effort by the Mayor Michelle Wu’s Office of Historic Preservation to move through a backlog of community- filed petitions that span several decades, a 1995 petition to grant city landmark status to the Massachusetts Port Authority-owned Fish Pier has resurfaced.

“The Fish is Pier is also an architectural treasure,” reads the 1995 petition, “a colorful marriage of Georgian simplicity and proportions and solid Romanesque archways and materials. Above the arches are scrolls and likenesses of Neptune, God of the sea. The smaller of the three buildings has decorated concrete pediments with bas relief sculpture of sea motifs.”

The age of the petition and the pier’s existing status as a state-owned property that is already on the National Register of Historic Places has raised some questions about whether another designation is necessary, and how it could affect the area’s growing businesses.

The Seaport’s city councilor, Ed Flynn, is voicing his opposition both to the potential designation and to how the process has unfolded so far.

“I don't think it’s necessary, Flynn said in an interview. “This is a Massport-owned property. It’s a state asset. It’s under regulations and guidelines established over many years by Massport and the process is working well. We don’t need to add another level of bureaucracy from the city government.”

A listing in the National Register of Historic Places puts no restrictions on what a non-federal owner may do with their property, unless the property is involved in a project that receives public funds.

Because the Fish Pier is owned by the Massport, structural changes made by the state already must go through a process dictated by the Massachusetts State Historic Preservation Office. If added to the city landmarks registry, an additional approval process, as determined by a hearing of the Boston Landmarks Commission (BLC), may need to be met.

“The project is expected to appear on the (BLC) agenda this month without any community process or notifications to neighbors or businesses,” Flynn said. “That’s a problem.”

Under the city’s landmarking procedure, once a petition is accepted, a study report is prepared to assess the historical and architectural significance of the property. The report is posted for a 21-day public comment period before a hearing is held. The BLC said in a statement given over email that the study report has been drafted but is not yet publicly available.

If the BLC votes to approve the designation, the decision then moves to the mayor, who has 15 days to respond. If the mayor signs off, or takes no action, the petition proceeds to the City Council for a final vote within 30 days. In January, Boston City Hall was granted landmark status by default, when the City Council failed to hold a vote within that 30-day period following Mayor Wu’s approval.

Flynn contends that city oversight could interfere with the daily operations of businesses that rely on flexibility to maintain facilities and infrastructure. He added that both governors and mayors have long recognized the pier’s economic value and left it largely untouched by broader redevelopment efforts.

“If one of the seafood companies needs to do some work on their building, what impact would a landmark designation have?” Flynn asked. “Those issues are unclear right now, and that’s exactly why a hearing is needed before we move forward.”

Summer was sensual

Hummock on the coast of Quincy, Mass., the town where Henry Adams grew up. Back then, much of it was semi-rural.

“Winter and summer, then, were two hostile lives, and bred two separate natures. Winter was always the effort to live; summer was tropical license. Whether the children rolled in the grass, or waded in the brook, or swam in the salt ocean, or sailed in the bay, or fished for smelts in the creeks, or netted minnows in the salt-marshes, or took to the pine-woods and the granite quarries, or chased musk-rats and hunted snapping turtles in the swamps, or mushrooms or nuts on the autumn hills, summer and country were always sensual living, while winter was always compulsory learning. Summer was the multiplicity of nature; winter was school.”

— From The Education of Henry Adams, by Henry Adams (1838-1918), famed writer, most notably as an historian. His paternal grandfather was President John Quincy Adams,who was a son of Founding Father and second President John Adams.

Time to move your car again

“Spring on Beacon,” by Meghan Weeks, at Copley Society of Art, Boston.

Chris Powell: More government and so, of course, more lobbyists

1891 cartoon of a legislator besieged by lobbyists.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Lobbyists in Connecticut have a bad reputation, and it may get worse with the recent report from the Office of State Ethics that spending on lobbyists exceeded $28 million in the first quarter of this year and may reach a record high by the end of the year.

Why is there so much lobbying?

Mainly because there is so much government.

A telling clue is that that the organization spending the most on lobbyists in the first quarter was the Connecticut Hospital Association, at $1.45 million. Other big spending on lobbyists in the first quarter also involved medicine: the Partnership for America's Health Care Future, representing hospitals, medical insurers and drug manufacturers, at $349,000; Hartford HealthCare, at $248,266; the Connecticut Association of Health Plans, at $230,370; Elevance Health and Affiliates, with $214,940; and Yale New Haven Health System, at $214,447.

Again, this spending was just for the first quarter.

No businesses are more subject to government spending and regulation than hospitals, medical insurers, and drug manufacturers. Modern medicine is now largely a matter of price-fixing and cost-shifting by government, what with Medicare, Medicaid and legislative and regulatory mandates.

Even a small change in law, regulation, or government policy can have huge financial impact on the components of medical case, and, of course, huge impact on patients and policyholders.

Whether these laws, regulations and policies are good or bad, they are pervasive, and so all the entities affected need to watch the government around the clock and intervene urgently on behalf of their interests.

Legislators and governors are supposed to represent the public interest, but the lobbyists work at the state Capitol nearly every day while their constituents are just trying to make a living and to get home in time for dinner and some television. The programs they watch are not about public policy.

Many lobbyists are often well paid for subverting the public interest in favor of a special interest. So special interests sometimes provide disguises for their lobbyists.

That's why the Partnership for America's Health Care Future doesn't call itself what it really is -- the Partnership for the Prosperity of Hospitals, Medical Insurers and Drug Manufacturers -- and why the Connecticut Education Association doesn't call itself the Connecticut Teachers Union.

Even so, lobbyists are crucial for democracy and the legislative process, especially on the state level. For while the governor and legislative committees can draw on expertise from the Office of Legislative Research and state government agencies, lobbyists often have much relevant information that government doesn't have -- and not just information but insight about policies and how they are likely to be received not just by special interests but the public as well.

Thirty-seven years ago, in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal, the General Assembly and Gov. Ella T. Grasso seemed to think that lobbyists were the nexus of political corruption. So a law was enacted requiring lobbyists to register with the Office of State Ethics and wear special badges on the job. The implication was that lobbyists had the plague and legislators shouldn't want to be around them.

Caution was in order but it wasn't because lobbyists had the plague and weren't identifying themselves. It was because legislators had a sort of plague -- the desperate craving for campaign contributions -- and were easily tempted to seek them first from the special interests represented by the lobbyists. Tagged with badges, lobbyists became easier to shake down.

Indeed, years ago neophyte candidates for the legislature who sought advice about raising campaign money were urged to visit the Office of State Ethics, ask for a list of all the lobbyists, and start there.

Things are a bit better now. Campaign contributions from lobbyists are restricted, and the state has a program of public financing of campaigns that diminishes need for special-interest money.

But special-interest money still abounds in politics, and, as always, the best defenses against bad law and corruption are vigorous news organizations and an attentive public. They are much weaker these days.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Gilded Age luminary

From Richard Morris Hunt’s sketchbook of a European trip, July to December 1874, (graphite and watercolor on paper), in the show “Richard Morris Hunt in a New Light,’’ at Newport Mansions.

The curator says:

“Hunt, the premier architect of the Gilded Age, is known for such imposing works as Marble House and The Breakers, in Newport, R.I. This exhibition will take a more intimate look at his life, creativity and ideas. For the first time, the exhibition will bring together Hunt’s personal sketchbooks, scrapbooks, architectural and interior drawings and family objects, drawn from the Library of Congress, Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Vermont Historical Society, Bennington (Vt.) Museum, the Preservation Society of Newport County’s collections and more.

Philip K. Howard: Code Red for red-tape America and what to do about it

Politics now has a dizzying quality. The roller-coaster of Trump policies―now we do this, now we do the opposite―is being matched by wild swings in the Democratic positions, led by socialist Zohran Mamdani's victory in the New York City mayoral primary. Just imagine, as liberal columnist Joe Klein mused, the staggering inefficiency of a municipal grocery store operating under union work rules: “Sorry, I only restock on Thursdays."

Centrist Democrats are trying to mobilize an “Abundance’’ agenda to cut through red tape to build housing and infrastructure. That's a step in the right direction, but pruning the red-tape jungle doesn't work by itself. Officials must have authority to make trade-off judgments.

The unimaginable tragedy of the flood in Texas on July 4 probably could have been averted in numerous ways. But several serious mistakes can be traced to the compliance philosophy of the red- tape state. Consider:A firefighter on duty asked dispatch about issuing a CodeRED alert but was told that that couldn’t be done could without a supervisor's approval. Some federal rescue workers weren’t mobilized immediately because of a new edict requiring the approval of the Homeland Security secretary for all expenditures over $100,000.

Nothing works without human judgment. What's missing in the political cacophony is the simple realization that things don't work because Americans are no longer allowed to roll up their sleeves and make things work. This is not a flaw that can be fixed by DOGE's indiscriminate cuts, nor by simply aspiring to Abundance. The red-tape state fails because it is a version of central planning―smothering teachers, principals, doctors, nurses, officials and all of us in red tape everywhere.

New leaders, new policies and new reforms are not sufficient. American government requires an intervention. Like it or not, the only cure is to transition away from the red-tape megalith to a governing framework activated by human responsibility. This is not radical. It is the founding philosophy of the Constitution, a document of 7,500 words―in contrast to the 150 million words of current federal law and regulation.Honoring human responsibility will also go a long way to overcoming the populist resentment that is fueling political craziness.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer and civic leader, is chairman of Common Good, a nonprofit legal-and-regulatory-reform organization.

He describes the principles and framework of what's needed in his forthcoming book: Saving Can-Do: How to Revive the Spirit of America (Rodin Books, Sept. 23).

Writing in The Washington Post, Dominic Pino cited Mr. Howard’s book Not Accountable on why public-employee unions should be considered unconstitutional.

Common Good’s work on why DOGE's cuts are misguided was highlighted in The New Yorker, and in interviews with WORLD and the America Trends Podcast.

Mr. Howard also discussed government reform with Daniel Wiig of the NYCLA Amicus Curiae podcast and on the The Aaron Renn Show.

Marvel at salt marshes

“Messages from the Marsh’’ (Part 5, video still 10, archival exhibition pigment print (Platine)), by Amy Kaczur in her joint show “The Great Muse —Three Artists Working With the Great Muse,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through July 27.

The gallery says that the show, with Kaczur, Resa Blatman and Max Schenk, is either “inspired by or touches on the beauty and ecological significance of salt marshes.’’