Vox clamantis in deserto

Maybe you'll meet them later

“Study for The Hours,’’ in the Pennsylvania State Capitol (detail), ca. 1909–11 (oil on canvas), by Edwin Austin Abbey, in the show “The Dance of Life: Figure and Imagination in American Art, 1876-1917, ‘‘ at the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn.

Llewellyn King: The agony and heroism of wonderful and awful Florida, in the hurricane expressway

The Florida National Guard cleaning up damage in Keaton Beach, Fla., following Hurricane Helene.

Cry, beloved Florida.

Florida, where the old go to rest — their reward after life’s labors — and the young go to play at its great amusement parks; where the rich live in Palm Beach and shop on Worth Avenue, and the poor harbor west of I-95; where citrus grows; where the Everglades record natural history from a time past; and where, in Key West, writers and artists find their nirvana of social misfits, drunks, addicts and creators, funky and inspiring.

Florida, where Apollo 11 took us to the Moon and where many a person from troubled lands has found refuge.

Florida, where Miami is a jewel in the crown of creativity and for all Spanish-speaking Latin Americans, their El Dorado.

On the night of Oct. 9, a night of horror and fear, Hurricane Milton delivered a cruel and malevolent blow, made the more so by its accompanying and capricious tornadoes. They were be spared nothing, the people and the animals of the Sunshine State, savaged by this terrible storm named, ironically, Milton — a name that invokes the great English poet, who said on going blind, “They also serve who only stand and wait.”

We, in our way, far from the storm, stood and waited, glued to our televisions and computers as we watched reality unfold; the threat of death arrived, buildings collapsed, metal flew, trees tumbled and first responders, the ever-ready shock troops of society got to work. Our time to serve is now with our generosity as the broken mend, having lost all they possess.

Yet, where we saw tragedy, we saw heroism.

All those heroes will never be counted to the last person, but they helped get Florida through its night of horror, just as they helped Florida and North Carolina after Hurricane Helene.

They, the first responders, are many, from the military to the police, the firefighters, the ambulance staff, the nurses and doctors, down to the assistants and porters.

One should add the electric linemen and women who seek to restore power, de-energize felled lines and start the vital work of saving lives by getting the lights on so that society can begin the journey back to normalcy in everything from bathing to cooking to making contact with those who have worried in silence — those who wonder if loved ones have survived.

This time around, the electrical workers are particularly stressed. Many have been working night and day since Helene swept through. Now they must lift the load again.

It is little known -- so little celebrated -- how the electric utilities are part of an extraordinary network of mutual assistance in which linemen and women board their trucks and drive hundreds even thousands of miles to begin the vital work of making fallen lines safe and restoring power. Sometimes they sleep in their vehicles or share what accommodation can be found.

In Florida and North Carolina, electrical workers will be laboring in dangerous conditions for weeks until the lights come back on and shattered lives again feel the balm of electrical service.

Raise a toast to the men and women who climb the poles in unfamiliar locales, sometimes warding off wild creatures, from snakes to civet cats, which have sought safety from floodwaters up electric poles.

They will be hampered, as will builders and the army of repair people who will be working for a long time because of a supply chain crisis. This will be felt in every aspect of the restoration in the storm-ravaged areas, but maybe most acutely so in the electric sector.

Much heavy electrical equipment, like large transformers and generators, is bespoke, made-to-order, often in China. This has presented an ongoing crisis for some time, which will gain attention as the rebuilding takes place. Even small transformers for poles are in short supply.

Artisans can work around materials shortages with ingenuity, but in the electric power system that is a limited option; it can’t be fixed with a compromise.

While bending knee to first responders, let us not forget the reporters, broadcast and print, who brought us the long night of Milton with disregard for personal safety. We saw the rain-soaked TV reporters bending into the wind lashed by rain, standing knee-deep in rising water, and sharing with us the potential lethality of airborne roofs and tree limbs.

But they weren’t alone. Behind every reporter is a chain of people from producers to camera operators to sound engineers to those who install and operate emergency generators. And don’t forget the writers, unseen, but on the front lines of the destruction.

The main compensation is the camaraderie of those who respond, those who march into tragedy to save lives and restore normalcy, and those from the Fourth Estate who rush there to tell us all about it.

Get well, Florida, and immeasurable thanks to those who were on hand to bind your wounds in your night of need and afterwards.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.co and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Where rent for a parking space can cost as much as that of an apartment

Excerpted from The Boston Guardian

(New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

Investing hundreds of thousands of dollars into your very own asphalt rectangle seems excessive, but Boston realtors are kicking themselves for not grabbing up parking spaces 20 years ago for less than $15,000. Today, the monthly mortgage on purchasing a private parking space in Back Bay, Beacon Hill or Downtown ranging from $150,000 to over $500,000 can be as much as rent on a single-bedroom apartment.

The steep price of private parking is a reflection of a city that’s broadly becoming less car-reliant while rising housing costs replace renters with condo purchasers willing or able to consider the price supplementary to the cost of home ownership. As the median cost of homes in Downtown has ballooned to around $1.5 million, parking space costs have similarly accelerated.

Year-to-year the availability of parking Downtown is in part regulated by the Air Pollution Control Commission, due to rules set by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1976.

Referred to as a “parking freeze,” the regulation set a cap on the number of commercially available parking spaces.

Forget the woodlot

“Solar Powered" (oil on cradled panel), by Sue Dragoo Lembo, at Alpers Fine Art, Rockport, Mass.

Keep this option alive

Boarding a Greyhound bus in downtown Salem, Ore., in 1964.

Entrance to the South Station Bus Terminal, in Boston, one of the nicest such facilities in America. That it is next to a big train station makes it even better. Sadly, many downtown bus terminals have been closed in the past few decades, with new ones, with minimal amenities, built next to windswept parking lots on the fringes of cities. Bus service is particularly important to low-and-middle-income people because bus tickets are obviously much cheaper than ones for plane and train travel.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Speaking of deserts, reading a CNN report the other day about the dearth of bus terminals in America reminded me of how important bus lines are for millions of Americans, though the mass of our automobile-bound population doesn’t think about them much. Many bus passengers can’t drive because they can’t afford a car or their health doesn’t permit it. Others just don’t want to drive a car, maybe because they fear there are just too many dangerously bad drivers on the road or because they can snooze and read on a bus.

Certainly getting more people out of cars and into public transportation would be very good for our air quality.

Where the private sector is unable or unwilling to step in, the Feds, states and cities should subsidize the construction and maintenance of bus terminals because of their important social, economic and environmental roles. They remain an important, if unfashionable and old-fashioned, part of our transportation network

I used to take buses a lot, first to get to school and then commuting in and out of Boston and other cities. It wasn’t as comfortable as taking the train but was usually less stressful than driving. But being stuck in buses before smoking was banned there was nauseating.

We’re lucky in southern New England in having much more access to trains than most other Americans. And after so many years in which train lines were killed, some have even been revived in the past couple of decades. One example is the train service connecting Boston’s South Shore that was closed in 1959, forcing commuters in and out of Boston to use the new Southeast Expressway, which swiftly became a miles-long parking for hours a day. I remember from when I was a boy how much more pleasant it was to ride in those rattling old rail cars to Boston’s South Station from Cohasset than in claustrophobic buses with decayed suspensions; buses are generally much more comfortable now. Of course the buses would get stuck in traffic, too, even after the creation of bus lanes.

In any event, a version of the train service was revived in 2007, to the relief of thousands.

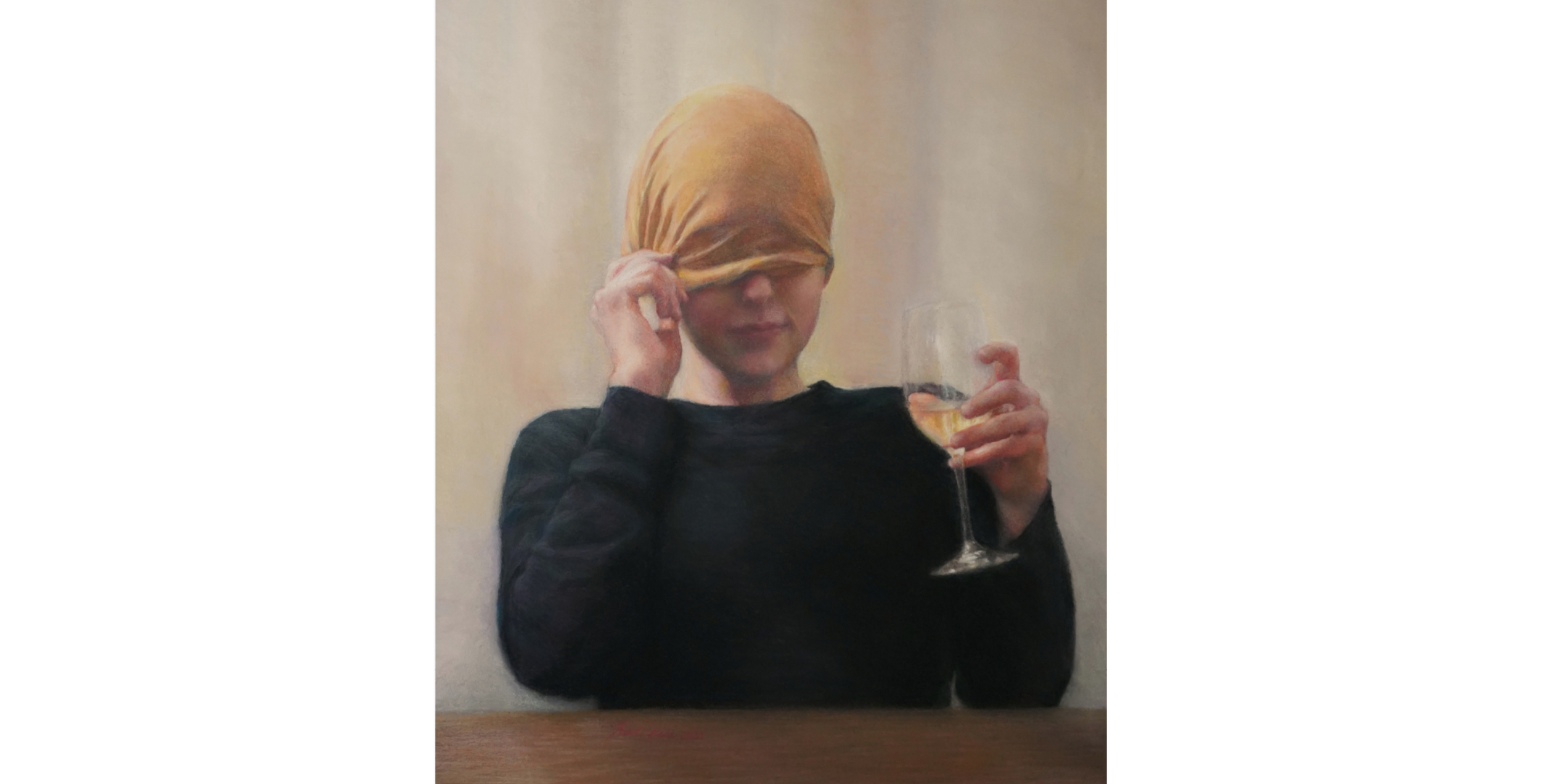

A household toy

“Mommy What Is This,’’ by Ileana Doble Hernandez, in her show “My Dear Americans,’’ at the Danforth Art Museum, Framingham, Mass., opening Oct. 12.

Busy despite the slump

In downtown Boston in 1933, the worst year of the Great Depression, when almost everyone wore a hat.

Narrative of grief ending in grace

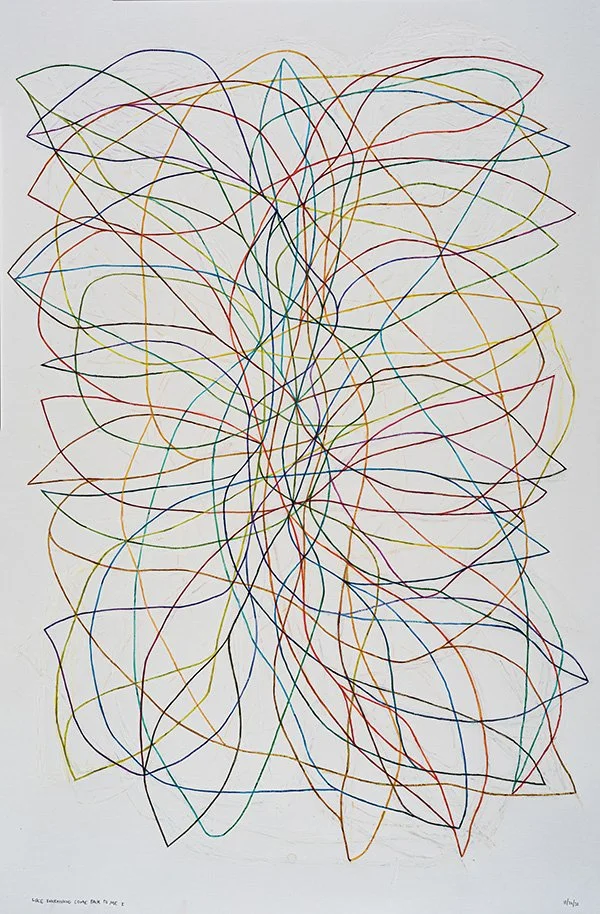

“Like Everything Come Back to Me” (watercolor and gouache on paper), by Peter Bruun in his show “Each Has Their Grief,’’ at 3S Artspace, Portsmouth, N.H., through Oct. 13.

The gallery explains:

“The exhibition follows a narrative arc through Bruun’s grief following the accidental overdose of his daughter ten years ago. Bruun’s figurative abstractions depict his story of loss and love, sorrow and serenity—landing at grace. Words, color, lines, and shape come together as if watching the mind pulse with thought and feeling, trying to process emotion.”

Bruun lives in Maine and Maryland.

Downtown Boston mostly comes back from the pandemic

Downtown Boston

State Theatre in Boston's old "Combat Zone'' in 1967.

-- Photo by Nick DeWolf

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Hope from history? Observers, including, me, remember how more moribund than now downtown Boston seemed half a century ago. Then big department stores were closing amidst suburban flight and the sleazy “Combat Zone’’ lurked nearby, scaring away people who wanted to be considered respectable.

The downtown is gradually coming back from the pandemic disaster, with new restaurants and other attractions opening. The COVID-accelerated move to remote work has affected some of the demographics of downtown consumers and changed the days and hours of peak business, but all in all “The Hub’s’’ center is looking pretty healthy. But it would look healthier if a lot more of the high-rise office space made empty by the remote-work revolution can be turned into housing, a very expensive and complicated architectural and engineering challenge.

xxx

It seems incredible that Newport would allow the demolition of a building as old as the beautiful if battered Borden House, built in 1704, when the city was one of the leading Colonial era ports, but a story in Newport This Week suggests that could well happen soon.

Longing for Indian summer

In the Berkshires

“Those grown old, who have had the youth bled from them by the jagged edged winds of winter, know sorrowfully that Indian summer is a sham to be met with hard-eyed cynicism. But the young wait anxiously, scanning the chill autumn skies for a sign of her coming.’’

— From Grace Metalious’s 1956 novel Peyton Place, set in a small New Hampshire town and considered by many at the time to be pornographic. It looks very tame now.

It's not all that bad

A flower, a skull, and an hourglass stand for life, death and time in this 17th-Century painting by Philippe de Champaigne.

To him who in the love of Nature holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language; for his gayer hours

She has a voice of gladness, and a smile

And eloquence of beauty, and she glides

Into his darker musings, with a mild

And healing sympathy, that steals away

Their sharpness, ere he is aware. When thoughts

Of the last bitter hour come like a blight

Over thy spirit, and sad images

Of the stern agony, and shroud, and pall,

And breathless darkness, and the narrow house,

Make thee to shudder, and grow sick at heart;—

Go forth, under the open sky, and list

To Nature’s teachings, while from all around

Earth and her waters, and the depths of air—

Comes a still voice—Yet a few days, and thee

The all-beholding sun shall see no more

In all his course; nor yet in the cold ground,

Where thy pale form was laid, with many tears,

Nor in the embrace of ocean, shall exist

Thy image. Earth, that nourished thee, shall claim

Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again,

And, lost each human trace, surrendering up

Thine individual being, shalt thou go

To mix for ever with the elements,

To be a brother to the insensible rock

And to the sluggish clod, which the rude swain

Turns with his share, and treads upon. The oak

Shall send his roots abroad, and pierce thy mould.

Yet not to thine eternal resting-place

Shalt thou retire alone, nor couldst thou wish

Couch more magnificent. Thou shalt lie down

With patriarchs of the infant world—with kings,

The powerful of the earth—the wise, the good,

Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past,

All in one mighty sepulchre. The hills

Rock-ribbed and ancient as the sun,—the vales

Stretching in pensive quietness between;

The venerable woods—rivers that move

In majesty, and the complaining brooks

That make the meadows green; and, poured round all,

Old Ocean’s gray and melancholy waste,—

Are but the solemn decorations all

Of the great tomb of man. The golden sun,

The planets, all the infinite host of heaven,

Are shining on the sad abodes of death,

Through the still lapse of ages. All that tread

The globe are but a handful to the tribes

That slumber in its bosom.—Take the wings

Of morning, pierce the Barcan wilderness,

Or lose thyself in the continuous woods

Where rolls the Oregon, and hears no sound,

Save his own dashings—yet the dead are there:

And millions in those solitudes, since first

The flight of years began, have laid them down

In their last sleep—the dead reign there alone.

So shalt thou rest, and what if thou withdraw

In silence from the living, and no friend

Take note of thy departure? All that breathe

Will share thy destiny. The gay will laugh

When thou art gone, the solemn brood of care

Plod on, and each one as before will chase

His favorite phantom; yet all these shall leave

Their mirth and their employments, and shall come

And make their bed with thee. As the long train

Of ages glide away, the sons of men,

The youth in life’s green spring, and he who goes

In the full strength of years, matron and maid,

The speechless babe, and the gray-headed man—

Shall one by one be gathered to thy side,

By those, who in their turn shall follow them.

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave,

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

— “Thanatopsis,’’ by William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878), American romantic poet and famed New York-based editor. He grew up in western Massachusetts.

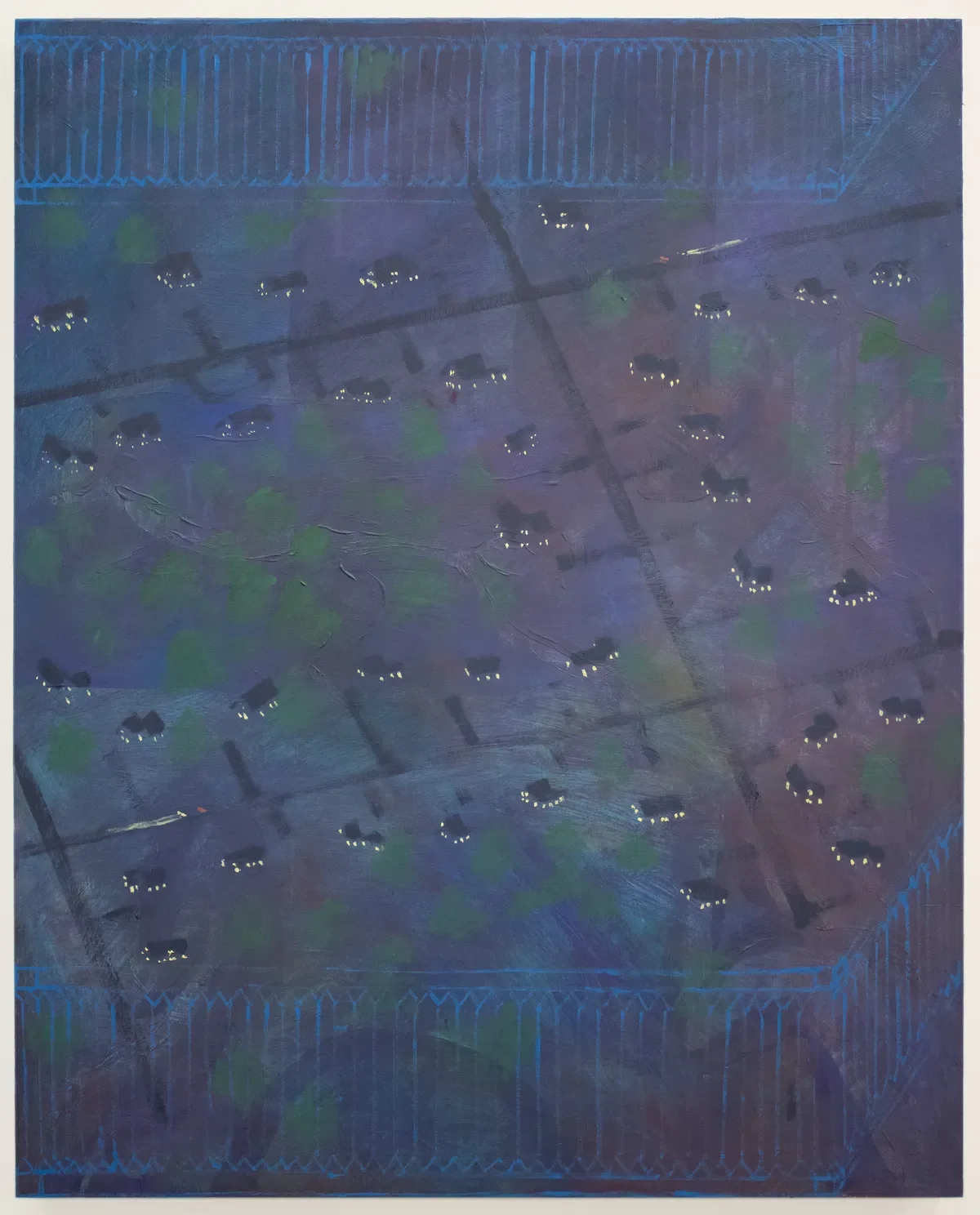

Transit textures

“Carscape #3,’’ by Maine painter Winslow Myers, in his show “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, opening Oct. 30.

The gallery says:

“In his first Boston show, modes of transport provide opportunities for the artist to play abstractly with form, space, color and light.’’

Above Logan International Airport, on Boston Harbor.

Chris Powell: Promote Connecticut’s gentle beauty and fix its government

Connecticut River as seen from Gillette Castle, in East Haddam, Conn.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

One of these days Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont may show Florida a thing or two. But probably not soon.

Without explanation, Florida's tourism Internet site recently removed a section touting destinations in the state said to be particularly attractive to members of sexual minorities. This renewed complaints that the state is hostile to those minorities because of its "Don't Say Gay" law, its refusal to let people change the sex listed on their driver's licenses, its prohibition of sex-change therapy for minors, and its requiring people to use restrooms corresponding to their biological sex.

As oppression goes, this isn't much. The "Don't Say Gay" law only forbids school class discussions of homosexuality in third grade and below, in the reasonable belief that any sex-related discussions aren't appropriate for younger children.

The prohibition on changing sex designations on driver's licenses guards against deception.

The prohibition on sex-change therapy for minors protects them against irreversible, life-changing treatment until they are fully able to make their own decisions. (All states prohibit certain things for minors, including Connecticut.)

Members of sexual minorities who live in Florida may disagree with these policies but apparently not enough to leave the state. Florida long has been and remains attractive to them, and their share of the population in Florida seems to equal or exceed their share of the country's population. An independent internet site on Florida tourism lists dozens of localities considered "gay-friendly," many with "gayborhoods," along with dozens of attractions that might appeal particularly to them.

And supposedly backward Florida has been gaining population while supposedly progressive Connecticut has been losing it.

So having already appealed to Florida businesses to relocate to Connecticut because of Florida's restrictive abortion law -- a law that probably will be liberalized by voters in a referendum in November -- Governor Lamont this month had Connecticut's tourism office undertake an internet advertising campaign aimed at sexual minorities, emphasizing the state as "a welcoming alternative."

Of course this campaign won't be any more effective than was the governor's appeal to Florida businesses to relocate to Connecticut because of abortion law. Both undertakings are just politically correct posturing by the governor, a Democrat who has been finding it harder to maintain the support of his party's extreme left. His posturing won't do much to keep the lefties in line either.

If only the governor could plausibly issue an appeal to Floridians, including the many who used to live in Connecticut (among them former Gov. Jodi Rell), that they should return here because of, say, the stunning new efficiency of state and municipal government, much-improved public education, reduction in taxes, and a rising standard of living.

After all, Florida's weather isn't that state's only attraction; it's not even all that good. Florida's winter can be lovely while Connecticut shivers, shovels, slips, and crashes. But Florida's summer can be oppressively hot, rain there can go on for days and is often torrential, hurricanes are frequent and can be catastrophic, and the state is full of mosquitoes, alligators, Burmese pythons, and cranky old people driving haphazardly to and from their doctor's office.

Florida's lack of a state income tax may be a bigger draw than its weather. While tax revenue from the state's tourism industry takes much financial pressure off state government, so does Florida's refusal to be taken over by the government class, a big difference from Connecticut. Florida's strengthening Republican Party may help in that respect, even as Connecticut's Republican Party and political competition in the state have nearly disappeared.

Connecticut's natural advantages remain what they always have been. Beautiful hills, valleys, meadows, forests, rivers, streams, lakes, a long seashore, changeable but generally moderate weather, and nearness to but comfortable distance from two metropolitan areas. It is a great but gentle beauty, crowned with convenience.

That is, Connecticut is a state to be lived in, not visited. Indeed, contrary to the governor's latest pose, the fewer tourists here, the better. Connecticut would be more wonderful still if government didn't keep making it more expensive, thus making Florida seem better.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Aid to navigation

From the series “Another America,’’ by Philip Toledano. He’s in the group show “Artificial Intelligence: DisInformation in a Post Truth World,’’ at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Winchester, Mass. through Oct. 27.

Train at the Winchester MBTA station in October 2008, between the Town Hall and the First Congregational Church. Winchester is an affluent inner suburb of Boston.

The museum says the show focuses on how images inform, persuade and drive the conversation about critical thinking.

Northeastern University breaks ground on Portland campus

-- Northeastern University's rendition of what its Roux Institute campus on the Portland waterfront will look like.

Edited from a New England Council report

“On Friday, Sept. 13, New England Council member Northeastern University held a groundbreaking ceremony to mark construction on its new campus in Portland, Maine, that will let the university to double the student body at the location.

“The Roux Institute at Northeastern University’s new campus will mark a significant step forward for Northeastern. The institute opened in 2020, thanks to a $100 million donation from technology entrepreneur David Roux, a Maine native, as well as another $100 million gift months later. The school has 800 students today, but it expects to have room for 2,000 when the new campus is completed, in 2028. The Roux is focused on technology research and development and graduate education.

“‘Our mission is to be a driver of the future Maine economy…. A larger permanent home for the university’s efforts in Maine is essential,’ the Roux Institute’s chief administrative officer, Chris Mallett, said in an interview.’’

Maniacal in Maine

Installation view of “Alive & Kicking: Fantastic Installations by Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, Catalina Schliebener Muñoz, and Gladys Nilsson,’’ at the Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine, through Nov. 11.

—Photography by Andrew Witte

City Hall and Opera House in 1905 in Waterville, where appreciation for the arts goes way back.

James L. Fitzsimmons: Of hurricanes and Huracan

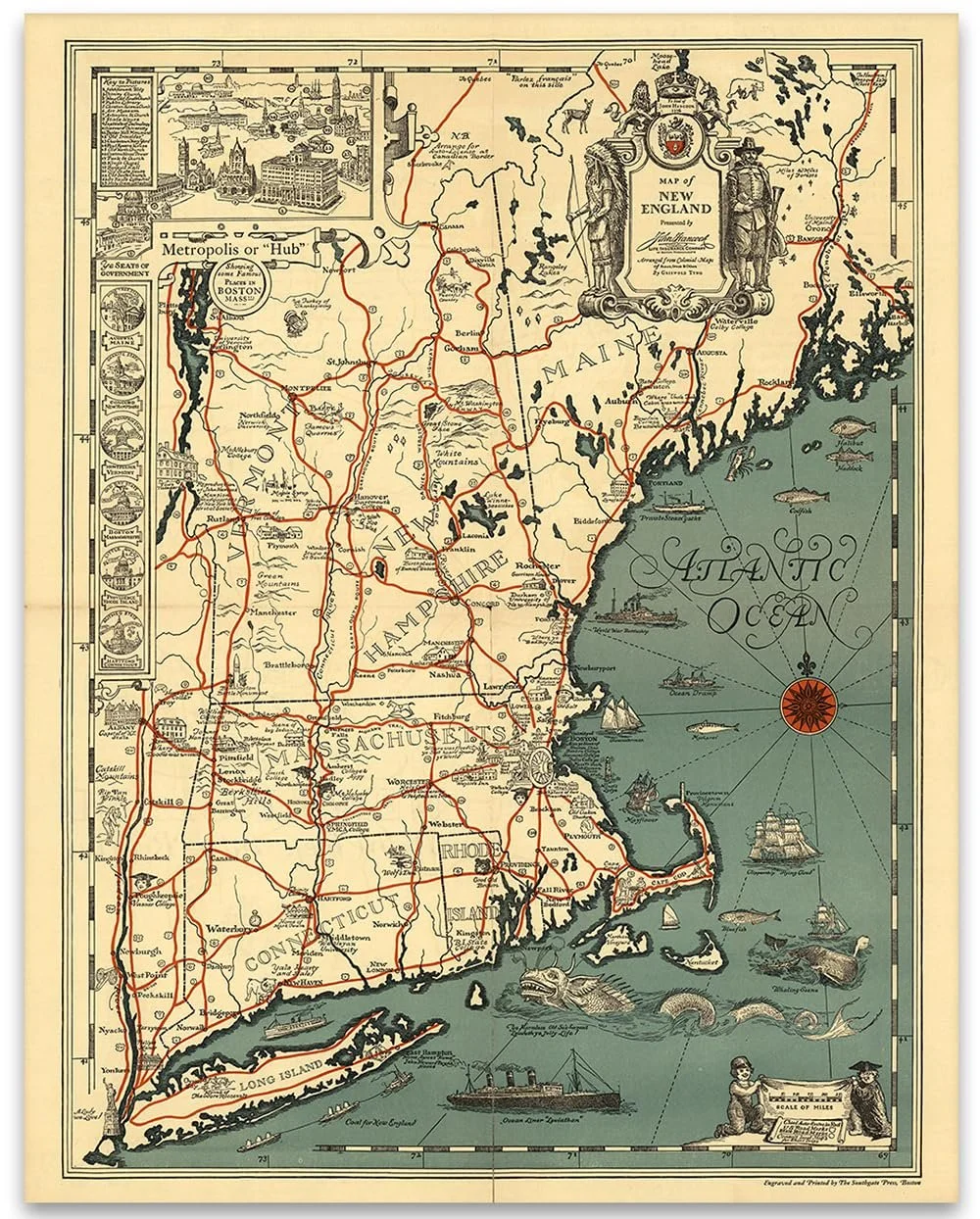

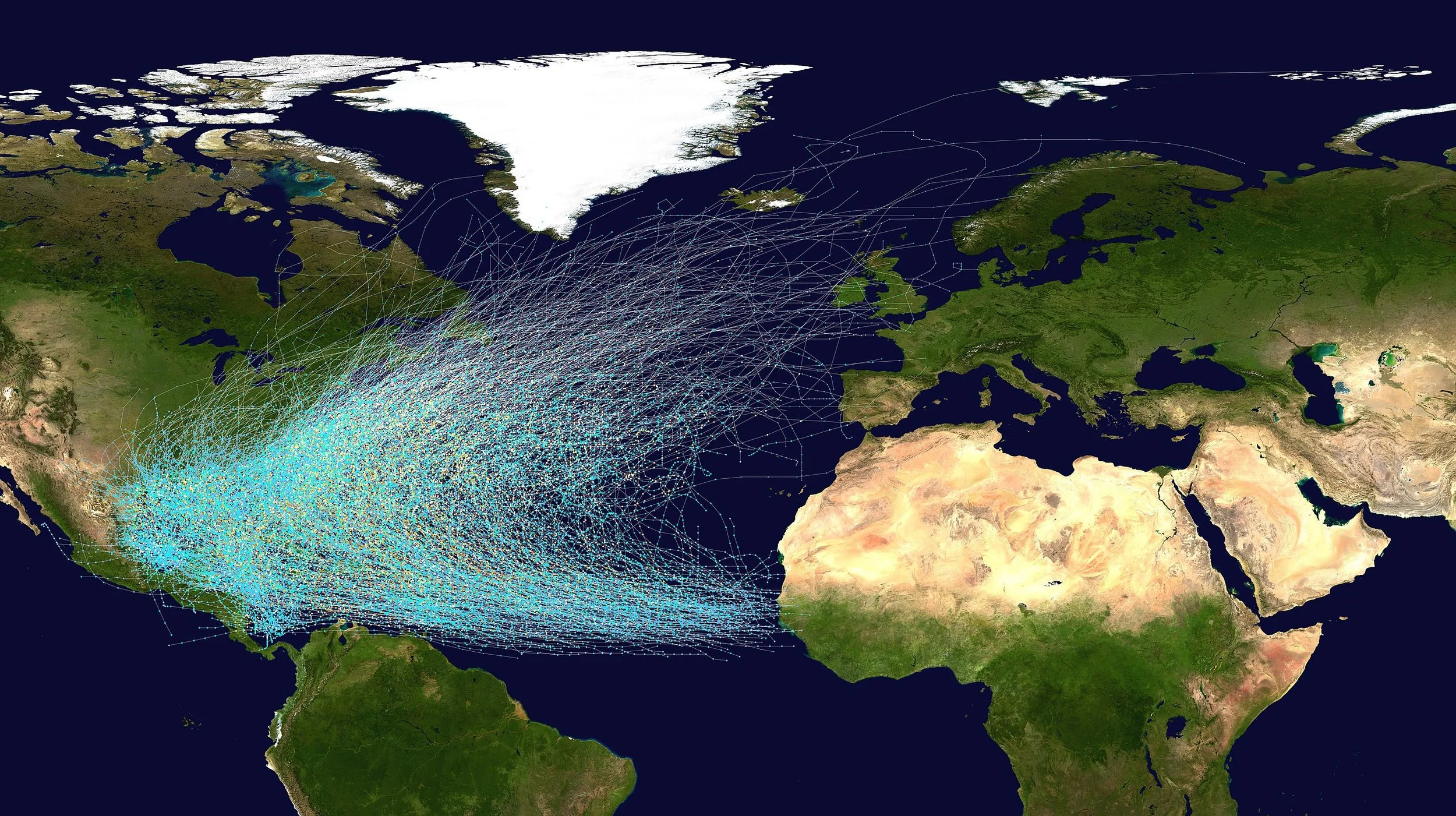

Tracks of North Atlantic tropical cyclones 1851-2019

MIDDLEBURY, Vt.

The ancient Maya believed that everything in the universe, from the natural world to everyday experiences, was part of a single, powerful spiritual force. They were not polytheists who worshipped distinct gods but pantheists who believed that various gods were just manifestations of that force.

Some of the best evidence for this comes from the behavior of two of the most powerful beings of the Maya world: The first is a creator god whose name is still spoken by millions of people every fall – Huracán, or “Hurricane.” The second is a god of lightning, K'awiil, from the early first millennium C.E.

As a scholar of the Indigenous religions of the Americas, I recognize that these beings, though separated by over 1,000 years, are related and can teach us something about our relationship to the natural world.

Huracán, the ‘Heart of Sky’

Huracán was once a god of the K’iche’, one of the Maya peoples who today live in the southern highlands of Guatemala. He was one of the main characters of the Popol Vuh, a religious text from the 16th century. His name probably originated in the Caribbean, where other cultures used it to describe the destructive power of storms.

The K’iche’ associated Huracán, which means “one leg” in the K’iche’ language, with weather. He was also their primary god of creation and was responsible for all life on earth, including humans.

Because of this, he was sometimes known as U K'ux K'aj, or “Heart of Sky.” In the K'iche’ language, k'ux was not only the heart but also the spark of life, the source of all thought and imagination.

Yet, Huracán was not perfect. He made mistakes and occasionally destroyed his creations. He was also a jealous god who damaged humans so they would not be his equal. In one such episode, he is believed to have clouded their vision, thus preventing them from being able to see the universe as he saw it.

Huracán was one being who existed as three distinct persons: Thunderbolt Huracán, Youngest Thunderbolt and Sudden Thunderbolt. Each of them embodied different types of lightning, ranging from enormous bolts to small or sudden flashes of light.

Despite the fact that he was a god of lightning, there were no strict boundaries between his powers and the powers of other gods. Any of them might wield lightning, or create humanity, or destroy the Earth.

Another storm god

The Popol Vuh implies that gods could mix and match their powers at will, but other religious texts are more explicit. One thousand years before the Popol Vuh was written, there was a different version of Huracán called K'awiil. During the first millennium, people from southern Mexico to western Honduras venerated him as a god of agriculture, lightning and royalty.

The ancient Maya god K'awiil, left, had an ax or torch in his forehead as well as a snake in place of his right leg. K5164 from the Justin Kerr Maya archive, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C., CC BY-SA

Illustrations of K'awiil can be found everywhere on Maya pottery and sculpture. He is almost human in many depictions: He has two arms, two legs and a head. But his forehead is the spark of life – and so it usually has something that produces sparks sticking out of it, such as a flint ax or a flaming torch. And one of his legs does not end in a foot. In its place is a snake with an open mouth, from which another being often emerges.

Indeed, rulers, and even gods, once performed ceremonies to K'awiil in order to try and summon other supernatural beings. As personified lightning, he was believed to create portals to other worlds, through which ancestors and gods might travel.

Representation of power

For the ancient Maya, lightning was raw power. It was basic to all creation and destruction. Because of this, the ancient Maya carved and painted many images of K'awiil. Scribes wrote about him as a kind of energy – as a god with “many faces,” or even as part of a triad similar to Huracán.

He was everywhere in ancient Maya art. But he was also never the focus. As raw power, he was used by others to achieve their ends.

Rain gods, for example, wielded him like an ax, creating sparks in seeds for agriculture. Conjurers summoned him, but mostly because they believed he could help them communicate with other creatures from other worlds. Rulers even carried scepters fashioned in his image during dances and processions.

Moreover, Maya artists always had K'awiil doing something or being used to make something happen. They believed that power was something you did, not something you had. Like a bolt of lightning, power was always shifting, always in motion.

An interdependent world

Because of this, the ancient Maya thought that reality was not static but ever-changing. There were no strict boundaries between space and time, the forces of nature or the animate and inanimate worlds.

Residents wade through a street flooded by Hurricane Helene, in Batabano, Mayabeque province, Cuba, on Sept. 26, 2024. AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa

Everything was malleable and interdependent. Theoretically, anything could become anything else – and everything was potentially a living being. Rulers could ritually turn themselves into gods. Sculptures could be hacked to death. Even natural features such as mountains were believed to be alive.

These ideas – common in pantheist societies – persist today in some communities in the Americas.

They were once mainstream, however, and were a part of K'iche’ religion 1,000 years later, in the time of Huracán. One of the lessons of the Popol Vuh, told during the episode where Huracán clouds human vision, is that the human perception of reality is an illusion.

The illusion is not that different things exist. Rather it is that they exist independent from one another. Huracán, in this sense, damaged himself by damaging his creations.

Hurricane season every year should remind us that human beings are not independent from nature but part of it. And like Hurácan, when we damage nature we damage ourselves.

James L. Fitzsimmons is a professor of anthropology at Middlebury College.

He does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

‘For the grapes’ sake’

Fall foliage in New Hampshire. (Photo by --bluepoint - Flickr)

O hushed October morning mild,

Thy leaves have ripened to the fall;

Tomorrow’s wind, if it be wild,

Should waste them all.

The crows above the forest call;

Tomorrow they may form and go.

O hushed October morning mild,

Begin the hours of this day slow.

Make the day seem to us less brief.

Hearts not averse to being beguiled,

Beguile us in the way you know.

Release one leaf at break of day;

At noon release another leaf;

One from our trees, one far away.

Retard the sun with gentle mist;

Enchant the land with amethyst.

Slow, slow!

For the grapes’ sake, if they were all,

Whose leaves already are burnt with frost,

Whose clustered fruit must else be lost—

For the grapes’ sake along the wall.

— “October,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Wild grapes in the fall. (Photo by Sten Porse)