Vox clamantis in deserto

Debby Waldman: Driving to Vermont to arrange to die

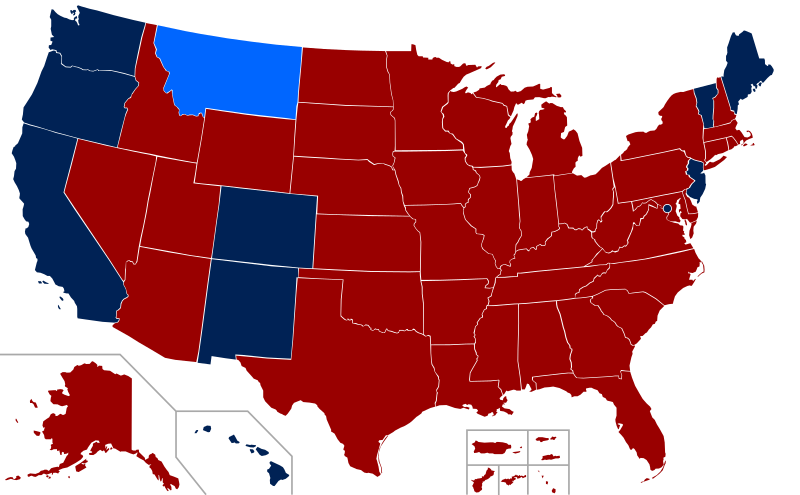

Legality of assisted suicide in the U.S. It’s clearly legal in dark blue states, legal in light blue Montana under a court order and illegal in red states.

Text From Kaiser Family Health News

In the 18 months after Francine Milano was diagnosed with a recurrence of the ovarian cancer she thought that she’d beaten 20 years ago, she traveled twice from her home in Pennsylvania to Vermont. She went not to ski, hike, or leaf-peep, but to arrange to die.

“I really wanted to take control over how I left this world,” said the 61-year-old who lives in Lancaster. “I decided that this was an option for me.”

Dying with medical assistance wasn’t an option when Milano learned in early 2023 that her disease was incurable. At that point, she would have had to travel to Switzerland — or live in the District of Columbia or one of the 10 states where medical aid in dying was legal.

But Vermont lifted its residency requirement in May 2023, followed by Oregon two months later. (Montana effectively allows aid in dying through a 2009 court decision, but that ruling doesn’t spell out rules around residency. And though New York and California recently considered legislation that would allow out-of-staters to secure aid in dying, neither provision passed.)

Despite the limited options and the challenges — such as finding doctors in a new state, figuring out where to die, and traveling when too sick to walk to the next room, let alone climb into a car — dozens have made the trek to the two states that have opened their doors to terminally ill nonresidents seeking aid in dying.

At least 26 people have traveled to Vermont to die, representing nearly 25% of the reported assisted deaths in the state from May 2023 through this June, according to the Vermont Department of Health. In Oregon, 23 out-of-state residents died using medical assistance in 2023, just over 6% of the state total, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

Oncologist Charles Blanke, whose clinic in Portland is devoted to end-of-life care, said he thinks that Oregon’s total is likely an undercount and he expects the numbers to grow. Over the past year, he said, he’s seen two to four out-of-state patients a week — about one-quarter of his practice — and fielded calls from across the U.S., including New York, the Carolinas, Florida and “tons from Texas.” But just because patients are willing to travel doesn’t mean it’s easy or that they get their desired outcome.

“The law is pretty strict about what has to be done,” Blanke said.

As in other states that allow what some call physician-assisted death or assisted suicide, Oregon and Vermont require patients to be assessed by two doctors. Patients must have less than six months to live, be mentally and cognitively sound, and be physically able to ingest the drugs to end their lives. Charts and records must be reviewed in the state; neglecting to do so constitutes practicing medicine out of state, which violates medical-licensing requirements. For the same reason, the patients must be in the state for the initial exam, when they request the drugs, and when they ingest them.

State legislatures impose those restrictions as safeguards — to balance the rights of patients seeking aid in dying with a legislative imperative not to pass laws that are harmful to anyone, said Peg Sandeen, CEO of the group Death With Dignity. Like many aid-in-dying advocates, however, she said such rules create undue burdens for people who are already suffering.

Diana Barnard, a Vermont palliative-care physician, said some patients cannot even come for their appointments. “They end up being sick or not feeling like traveling, so there’s rescheduling involved,” she said. “It’s asking people to use a significant part of their energy to come here when they really deserve to have the option closer to home.”

Those opposed to aid in dying include religious groups that say taking a life is immoral, and medical practitioners who argue their job is to make people more comfortable at the end of life, not to end the life itself.

Anthropologist Anita Hannig, who interviewed dozens of terminally ill patients while researching her 2022 book, The Day I Die: The Untold Story of Assisted Dying in America, said she doesn’t expect federal legislation to settle the issue anytime soon. As the U.S. Supreme Court did with abortion in 2022, it ruled assisted dying to be a states’ rights issue in 1997.

During the 2023-24 legislative sessions, 19 states (including Milano’s home state of Pennsylvania) considered aid-in-dying legislation, according to the advocacy group Compassion & Choices. Delaware was the sole state to pass it, but the governor has yet to act on it.

Sandeen said that many states initially pass restrictive laws — requiring 21-day wait times and psychiatric evaluations, for instance — only to eventually repeal provisions that prove unduly onerous. That makes her optimistic that more states will eventually follow Vermont and Oregon, she said.

Milano would have preferred to travel to neighboring New Jersey, where aid in dying has been legal since 2019, but its residency requirement made that a nonstarter. And though Oregon has more providers than the largely rural state of Vermont, Milano opted for the nine-hour car ride to Burlington because it was less physically and financially draining than a cross-country trip.

The logistics were key because Milano knew she’d have to return. When she traveled to Vermont in May 2023 with her husband and her brother, she wasn’t near death. She figured that the next time she was in Vermont, it would be to request the medication. Then she’d have to wait 15 days to receive it.

The waiting period is standard to ensure that a person has what Barnard calls “thoughtful time to contemplate the decision,” although she said most have done that long before. Some states have shortened the period or, like Oregon, have a waiver option.

That waiting period can be hard on patients, on top of being away from their health-care team, home, and family. Blanke said he has seen as many as 25 relatives attend the death of an Oregon resident, but out-of-staters usually bring only one person. And while finding a place to die can be a problem for Oregonians who are in care homes or hospitals that prohibit aid in dying, it’s especially challenging for nonresidents.

When Oregon lifted its residency requirement, Blanke advertised on Craigslist and used the results to compile a list of short-term accommodations, including Airbnbs, willing to allow patients to die there. Nonprofits in states with aid-in-dying laws also maintain such lists, Sandeen said.

Milano hasn’t gotten to the point where she needs to find a place to take the meds and end her life. In fact, because she had a relatively healthy year after her first trip to Vermont, she let her six-month approval period lapse.

In June, though, she headed back to open another six-month window. This time, she went with a girlfriend who has a camper van. They drove six hours to cross the state border, stopping at a playground and gift shop before sitting in a parking lot where Milano had a Zoom appointment with her doctors rather than driving three more hours to Burlington to meet in person.

“I don’t know if they do GPS tracking or IP address kind of stuff, but I would have been afraid not to be honest,” she said.

That’s not all that scares her. She worries she’ll be too sick to return to Vermont when she is ready to die. And, even if she can get there, she wonders whether she’ll have the courage to take the medication. About one-third of people approved for assisted death don’t follow through, Blanke said. For them, it’s often enough to know they have the meds — the control — to end their lives when they want.

Milano said she is grateful she has that power now while she’s still healthy enough to travel and enjoy life. “I just wish more people had the option,” she said.

In June, Milano headed to Vermont to open a second six-month window to receive medical aid in dying. After a six-hour drive, she crossed the state’s border and opted to Zoom with a doctor rather than drive three more hours to meet in person, as she had done the first time.

Debby Waldman is a Kaiser Family Health Plans journalist.

Related Topics

'The Wall' and fireflies

"The Wall'' at Hampton Beach, N.H.

Resting on Hampton Beach on a quiet September day.

“When the summer days end, the beauty of New England does not. Summer nights are arguably the best time of day. At the end of the day, we enjoy the most beautiful sea breeze. I’ve spent so many nights wrapped in a sweatshirt on the porch, counting the fireflies lighting up the yard. This weather also makes for the perfect bonfire. If we’re not at “The Wall, ‘‘ {in Hampton Beach, N.H.) it’s very likely that someone will have a fire in his/her yard. If you haven’t huddled up to a fire with your best friends, then I recommend doing so this summer (just make sure someone brings the ingredients for s’mores!).’’

— Abigail Loffredo, from her “New England Summers are the BEST Summers’’

Primacy in plumbing

Edited from From The Boston Guardian

In 1829, the Tremont Hotel opened at the corner of Tremont and Beacon streets in downtown Boston. It had 170 rooms that each rented for $2 a day and included four meals. In 1869 the Tremont became the first hotel in the U.S. to install indoor plumbing. Notable guests included Davy Crockett and Charles Dickens. In 1895, the hotel was razed and replaced with an office building.

Building blocks of scenery

“The Burren” (oil), by Jan Roy, at the Lakes Gallery at Chi-Lin, Laconia, N.H., through Sept. 8.

The Burren is a limestone area on Ireland’s North Clare coast. It’s famous for its wild flowers, caves and dolmens

View of Lake Winnipesaukee. Laconia is the largest town on the lake, a major summer vacation area.

Quilted news

“Lost Village” (commercial and hand-dyed cotton fabrics, commercial bias tape, machine pieced, appliqued and quilted), by Joe Cunningham, in his show “Quilts for These Times,’’ at the Cahoon Museum of American Art, Cotuit, Mass., through Sept. 15.

This series of 10 quilts marks a turning point for the artist as each quilt addresses current events.

Those jumping worms

Jumping worms

-- Photo by Njh5880

Excerpted from an ecoRI News article

CRANSTON, R.I.

“An infestation of jumping worms, also known as snake worms, has forced the Rhode Island Wild Plant Society to cancel its August native plant sale.

Pat Foley, president of RIWPS, wrote in an email, ‘We have decided to cancel our upcoming native plant sale. Based on conversations I had this week with the volunteers planning the sale, we learned that invasive ‘jumping worms’ were discovered in some of the plant trays we were readying for the sale.’

“Even though the invasive worms look similar to the region’s more common earthworm, their behavior easily identifies them. They slither through the grass like snakes and jump away if they are disturbed. In their native Korea and Japan, they are called Asian jumping worms.’’

The subtractor

Adapted From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘Bally’s, the Providence-based gambling company, has told its investors that revenue is down because of the Washington Bridge failure. While the bridge mess reduces revenue to state government under its deal with the company, it also reduces the money taken from the pockets of gamblers who might decide not to go to Bally’s casinos in Lincoln and Tiverton because of the traffic tangles on and around the bridge. That’s money that won’t go to out-of-region investors. This could have a benign macroeconomic effect around here.

The money that’s not sent to these investors could be spent in buying goods and services from locally owned businesses – some that actually make or grow things -- or even in investing in them.

After all, gambling at venues like Bally’s doesn’t exactly increase a region’s long-term wealth; it subtracts from it, including via driving some gambling addicts into personal bankruptcies and bad behavior.

Whatever….

How it looked in 1667

Caption material from Wikipedia:

This map was published in 1667. It was created by engraver John Foster, and published as a guide to go with clergyman William Hubbard's publication A Narrative of the Troubles with Indians in New England, From the Planting Therof, to the Present Time. Originally printed in Boston, it is reputed to be the first map to have been published in the Western Hemisphere.

Chris Powell: Conn. isn’t prepared for greater prosperity; sneaky ‘public-benefits’ charges

Millstone Nuclear-Power Plant, in Waterford, Conn.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

When federal census data showed Connecticut's population increasing by about 57,000 in 2021 and 2022, Gov. Ned Lamont construed it as great news, evidence of the state's prosperity under his administration, a remarkable contrast with the population losses of nearby states.

But the other day the U.S. Census Bureau acknowledged that the population increase report was a mistake and that Connecticut probably experienced a population loss of 13,500 during that period.

In a way this may be construed as great too.

For the state has a severe shortage of housing, home prices and rents have been soaring, and homelessness is rising. Experts say the state needs at least 100,000 more housing units just for its current population to be able to live decently. If the state really had gained 57,000 people, it would be under much greater strain.

Connecticut isn't prepared for greater prosperity, and more strain is promised by the increased military contracting coming into the state for which thousands of new workers are needed.

Even if the national economy were entering a recession, Connecticut still would have thousands of inadequately housed people.

Equating construction of inexpensive housing with poverty because of the mess the state has made of its cities, Connecticut has been slow to recognize that its housing policy -- unfriendly if not hostile to new housing -- has been a disaster too.

But the Lamont administration has taken the hint and is proceeding with state government incentives for housing construction. Hartford and New Haven are encouraging apartments and condominiums and are showing that city living can attractive, and a few suburbs are viewing housing proposals more favorably than usual.

It's far from enough but it's a start. If housing initiatives continue for a few more years and state government discourages exclusive zoning and controls spending and taxes, maybe even accurate census data will start showing that more people want to move to Connecticut than leave it for lower-taxed states with milder winters.

xxx

Connecticut has among the highest electric rates in the country, and the big increases imposed last month are painful reminders that the state would have to reduce rates if it would increase its prosperity and population -- or even just maintain its population.

The latest rate increases have two major causes: the decision by the governor and General Assembly to guarantee purchase of the electricity generated by the Millstone nuclear-power plant, in Waterford, as a matter of Connecticut's energy security; and second, the "public benefits" charges that long have been largely hidden in customer electric bills, essentially sales taxes to finance state government programs having little if anything to do with generation and delivery of electricity.

Among the "public benefits" charges is one by which people who pay their electric bills are required to pay as well for people who don't pay but who under state law can't be disconnected during much of the year. Since this charge is a welfare expense, it should be borne by taxpayers generally, not by electricity users particularly.

Indeed, there is no good reason to charge electricity users particularly for any of the "public benefits" hidden in their bills. Insofar as electricity is a necessity of life, taxing it is no more justified than taxing food and medicine would be.

The real justification for financing the "public benefits" from a de-facto sales tax on electricity is that state legislators and governors have liked obscuring the costs of those "benefits" and deceiving the public into thinking that the big, bad electric companies are overcharging. By some estimates 20 percent of the cost of electricity for a typical Connecticut resident results from non-electrical "public benefits" charges.

Members of the General Assembly's Republican minority have been making an issue of this and fortunately have begun pressing it harder. "Public benefits" charges on electricity bills should be eliminated, along with the "public benefits" themselves, or else their costs should be recovered through general taxation or spending cuts elsewhere.

Now who wants to specify the tax increases or spending cuts necessary to get rid of the "public benefits" charges?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years(CPowell@cox.net).

‘The chowder shall not die’

New England clam chowder

“Alas, what crimes have been committed in the name of chowder! Dainty chintz-draped tea rooms, charity bazaars, church suppers, summer hotels, canning factories — all have shamelessly travestied one of America’s noblest institutions; yet while clams and onions last, the chowder shall not die.’’

— Louis P. De Gouy (1876-1947), in The Gold Cook Book

Virginia Raguin: Great art from flawed artists

Marko Rupnik

WORCESTER

Marko Rupnik, a Catholic priest, was expelled from the Jesuit order because he’d allegedly abused women. He was later accepted into the diocese in his native Slovenia. Rupnik is also an artist, and his work is on display in churches in Lourdes, Rome and Washington, D.C., among others.

Some of these sites are planning to cover or remove Rupnik’s art; some congregants and clergy disagree with such actions. The Vatican’s communication chief, Paolo Ruffini, for example, has defended the Holy See’s decision to keep Rupnik’s art on his department’s website.

As an art historian, I ask whether the debate is missing the point.

Bridging Eastern and Western European traditions

Rupnik’s art has been honored in the past as part of an effort by the Catholic Church to bridge Eastern and Western European faith traditions. With his heritage as a Slovenian, Rupnik was able to create imagery that blended both traditions. He was chosen in 1996 to decorate three of the four walls of the Redemptoris Mater Chapel of the Apostolic Palace in Vatican City with art that symbolized unity between the churches.

In 2016, Rupnik designed the logo for the Year of Mercy, a special spiritual jubilee declared by Pope Francis. Rupnik modeled Christ after the Eastern tradition of the “anastasis,” or resurrection, in which Christ is believed to have liberated the souls of the dead.

Rupnik was inspired by this 14th-Century fresco of the Anastasis at Instanbul’s Chora Church. Virginia Raguin, CC BY

Rupnik modeled his painting after a similarly themed 14th-century fresco at Istanbul’s Chora Church. He depicted Christ wearing a white robe, surrounded by an almond-shaped aureole of light. He placed Adam across Christ’s shoulders, a motif derived from early Christian images of Christ as the Good Shepherd.

His work echoed other historical precedents as well. Christ and Adam’s faces were pressed together and they shared a single eye to symbolize that Adam and Christ both shared a human nature. The motif of shared eyes to symbolize the single divine nature of the Christian Trinity appears in the art of the Renaissance.

Marko Rupnik, Anastasis. Collegio St. Stanislaus, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2006, realized by 'Atelier d’Arte e Architettura del Centro Aletti', Author provided (no reuse)

He was also commissioned to produce the mosaics that adorn St. John Paul II National Shrine in Washington, D.C.

Personal morality and creative production

Many revered works of art come from spiritually flawed creators. Raphael, whose frescoes, such as “The School of Athens,” adorn the room of the Segnatura in the Vatican, reportedly had many mistresses. Italian painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio lived a short and violent life. He killed a man in a brawl, resulting in his receiving the death sentence for murder. Nonetheless, many of his paintings are seen as deep expressions of faith.

Caravaggio’s “Entombment of Christ,” one of the greatest treasures of the Vatican, depicts the sorrow of Christ’s followers. The artist’s “Madonna of Loreto,” located in the church of Sant'Agostino in Rome, has long been admired for its ability to bring the divine into everyday life. Thin, circular halos hover behind the heads of the Virgin and Child, who otherwise appear as ordinary people and resemble the two barefoot peasants kneeling before them. At the painting’s unveiling in 1606, some were distressed by the lack of dignity in depicting the Virgin and her divine child as commoners.

Madonna and Child. Caravaggio, Basilica of Saint Augustine in Campo Marzio courtesy Virginia Raguin, CC BY

During my visit to Sant'Agostino in 2009, I witnessed scores of people viewing the painting. Spectators invariably stood next to the peasant’s feet, demonstrating that they could somehow empathize with the pair’s devotion. For over an hour, I was reminded of the power of art regardless of where it came from.

Artists – and all humans – are inevitably flawed; once finished, I believe, an artist’s work is independent of its creator.

From my perspective, condemning art, rather than debating how the Catholic Church may have allowed someone accused of abuse to avoid censure for so long, is a diversion at best.

Virginia Raguin is a professor of humanities emerita, at the College of the Holy Cross, in Worcester.

Virginia Raguin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond her academic appointment.

‘Between real and imaginary’

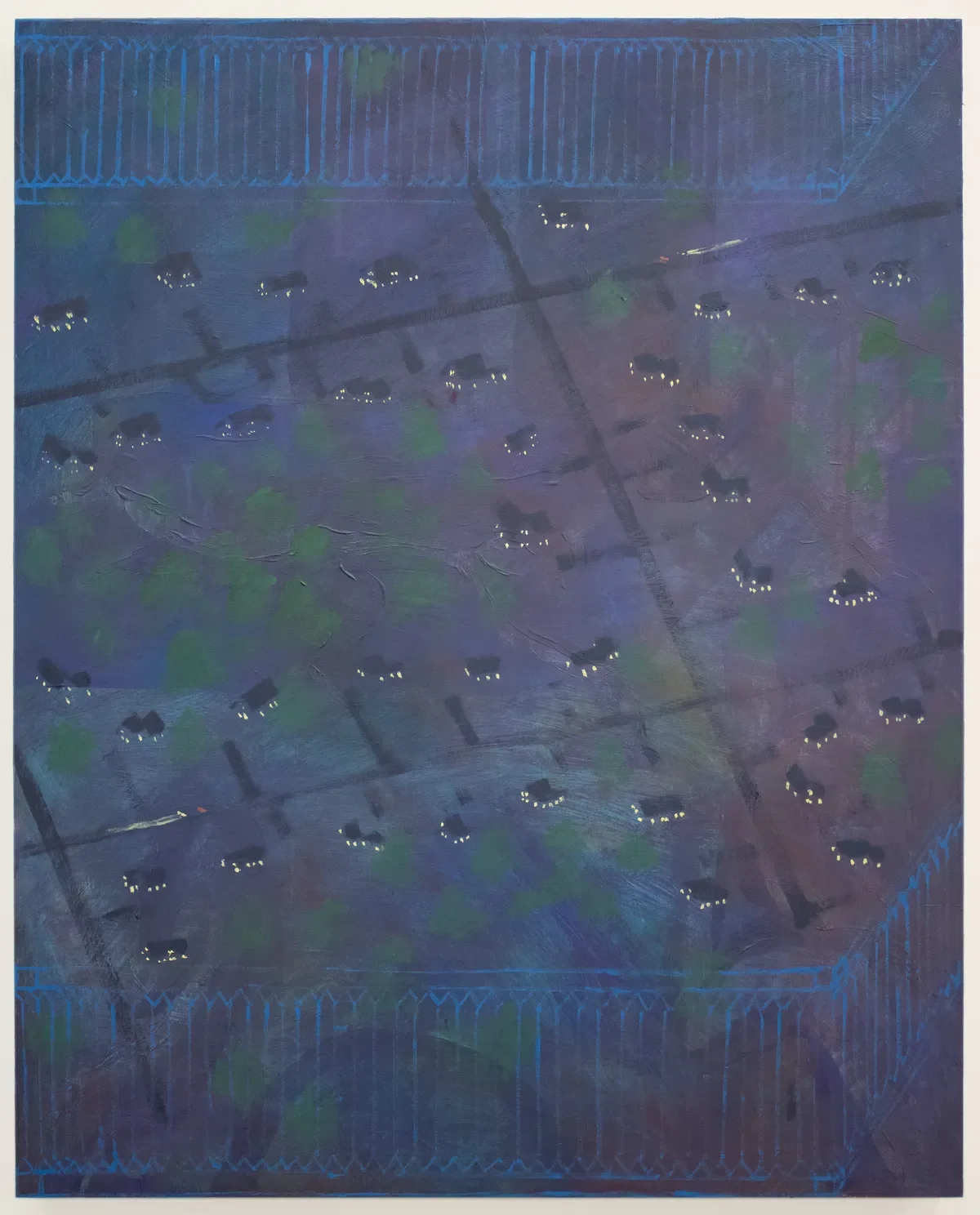

“Manana twilight”(acrylic on linen), by Dozier Bell, in her show “Genius loci,’’ at Sarah Bouchard Gallery, Woolwich, Maine, through Sept. 15.

The gallery says that Bell's work "embodies a reckoning with the unseen forces that shape and transform our lives," and her paintings "straddle the line between real and imaginary places while still evoking the powerful imagery of low-light scenes.''

In Woolwich around the turn of the last century.

Llewellyn King: What might happen if Google is broken up?

Google headquarters, in Mountain View, Calif.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Alphabet Inc.’s Google has few peers in the world of success. Founded on Sept. 4, 1998, it has a market capitalization of $1.98 trillion today.

It is global, envied, admired, and relied upon as the premier search engine. It is also hated. According to Google (yes, I googled it), it has 92 percent of the search business. Its name has entered English as a noun (google) and a verb (to google).

It has also swallowed so much of world’s advertising that it has been one of the chief instruments in the humbling and partial destruction of advertising-supported media, from local papers to the great names of publishing and television; all of which are suffering and many of which have failed, especially local radio and newspapers.

Google was the brainchild of two Stanford graduate students, Larry Page and Sergey Brin. In the course of its short history, it has changed the world.

When it arrived, it began to sweep away existing search engines quite simply because it was better, more flexible, amazingly easy to use, and it could produce an answer from a few words of inquiry.

There were seven major search engines fighting for market share back then: Yahoo, Alta Vista, Excite, Lycos, WebCrawler, Ask Jeeves and Netscape. A dozen others were in the market.

Since its initial success, Google, like Amazon, its giant tech compatriot, has grown beyond all imagination.

Google has continued its expansion by relentlessly buying other tech companies. According to its own search engine, Google has bought 256 smaller high-tech companies.

The question is: Is this a good thing? Is Google’s strategy to find talent and great, new businesses or to squelch potential rivals?

My guess is some of each. It has acquired a lot of talent through acquisition, but a lot of promising companies and their nascent products and services may never reach their potential under Google. They will be lost in the corporate weeds.

In the course of its acquisition binge, Google has changed the nature of tech startups. When Google itself launched, it was a time when startup companies made people rich when they went public, once they proved their mettle in the market.

Now, there is a new financing dynamic for tech startups: Venture capitalists ask if Google will buy the startup. The public doesn’t get a chance for a killing. Innovators have become farm teams for the biggies.

Europe has been seething about Google for a long time, and there are ongoing moves to break up Google there. Here, things were quiescent until the Department of Justice and a bipartisan group of attorneys general brought suit against the company for monopolizing the advertising market. If the U.S. efforts to bring Microsoft to heal is any guide, the case will drag on for years and finally die.

History doesn’t offer much guidance as to what would happen if Google were to be broken up; the best example and biggest since the Standard Oil breakup in 1911 is AT&T in 1992.

In both cases, the constituent parts grew faster than the parent. The AT&T breakup fostered the Baby Bells — some, like Verizon, have grown enormously. Standard Oil was the same: The parts were bigger than the sum had been.

When companies have merged with the government’s approval, the results have seldom been the corporate nirvana prophesied by those urging the merger, usually bankers and lawyers.

Case in point: the 1997 merger of McDonnell Douglas and Boeing. Overnight the nation went from having two large airframe manufacturers to having just one, Boeing. The price of that is now in the headlines as Boeing, without domestic competition, has fallen into the slothful ways of a monopoly.

Antitrust action against Google has few lessons to be learned from the past. Computer-related technology is just too dynamic; it moves too fast for the past to illustrate the future. That would have been true at any time in the past 20 years (the years of Google’s ascent), but it is more so now with the arrival of artificial intelligence.

If the Justice Department succeeds, and Google is broken up after many years of litigation and possible legislation, it may be unrecognizable as the Google of today.

It is reasonable to speculate that Google at the time of a breakup may be many times its current size. Artificial intelligence is expected to bring a new surge of growth to the big tech companies, which may change search engines altogether.

Am I assuming that the mighty ship Google is too big to sink? It hasn’t been a leader to date in AI and is reportedly playing catch up.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

UMaine setting up new aquaculture research and training center

Planned University of Maine aquaculture training and research center.

— Image courtesy of its architects, Andover, Mass.-based SMRT Architects and Engineers

Images from the book Maine Oysters: Stories of Resilience and Innovation

Edited from a New England Council report:

The University of Maine is working on a 14,200-square-foot addition to its Sustainable Workforce Innovation Center to serve the Pine Tree State’s growing aquaculture center.

Scheduled to open in 2025, at the university’s flagship campus, in Orono, the $10.3 million research and training center will prepare workers for aquaculture careers, and help the state address the challenges of its finfish, oyster and mussel farms.

“[The center] links research with teaching, so there’s classroom and research space together, and it brings in professionals from the aquaculture industry, academic researchers and experts and students to work together on identifying and addressing the kinds of issues that the aquaculture industry confronts,” said Trish Riley, chair of the University of Maine System Board of Trustees.

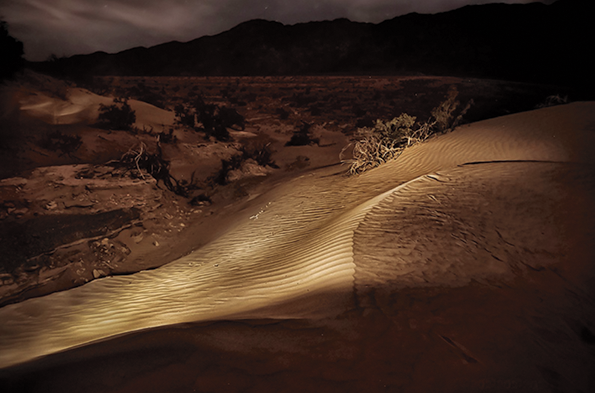

Bare-bones beauty

“Band of Light” (photo), by Massachusetts photographer Lisa Ryan, in the group show “Industrial Beauty-Luminous Desert,’’ at the Art Complex Museum, in Duxbury, Mass., opening Aug. 18.

David Warsh: We should pay more attention to this outfit

1050 Massachusetts Ave. in Cambridge, where the National Bureau of Economic Research is based.

— Photo by Astrophobe

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

An interesting fact: The leaders of Harvard University, Stanford University, Brown University and the University of California at Berkeley have something in common. Alan Garber, Jonathan Levin, Christina Paxson and Richard Lyons are all research associates of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Four out of 17,000+ NBER researchers, the preponderance of them economists, is not a large portion of the whole. But it may offer a hint of what top universities are looking for in their presidents.

The NBER is an unusual organization. Founded in 1920 by two individuals of very different outlooks, an executive of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company and a socialist labor organizer with a PhD from Columbia. Their idea was to fund independent studies of issues about which widespread differences of opinion existed: changes in the gap between rich and poor during the Gilded Age and the Progressive era, as well as the effects of large-scale immigration on wages. National income and its distribution have been the core of NBER studies ever since, along withe the structure of business cycles, too.

Since the 1970s, though, when its headquarters moved from New York City to Cambridge, Mass., and decentralized its research, a host of new topics have come under the NBER microscopes. Everything from the economics of health insurance and childhood education to inflation and national defense practices are investigated with imaginative theory, data, and statistical technique.

A look at the governance of the organization discloses the key to its success over a hundred years. Three classes of directors keep their eyes on the organization’s pursuits: a diverse collection of outsiders; a class of representatives of universities; and another of professional associations of one sort and another.

As in the days of its founding, the NBER seeks to bridge gaps between antagonistic factions. Its culture is suffused with respect for differences of opinion. Its goal is building consensus.

Would those characteristics be attractive to universities eager to get themselves off the front pages of newspapers?

Of course they would. A little more attention in those newspapers to NBER findings might help as well.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based Economic Principals.

The sound of nothing flapping

“Pintail Pair and Cattails’’ (wood), by Robert and Virginia Warfield, in the Jaffrey (N.H.) Historical Society’s show “The Warfield Collection,’’ at the Jaffrey Civic Center through Sept. 17. This exhibition consists of 50 exquisitely carved and painted birds produced between 1970 and 1990.

A cattail. They grow in New England marshes and kids love to whip them around.

Main Street in Jaffrey, in the Monadnock region, in 1907. The region has long had many artists and weekend and vacation homes.

The Mass. origins of the National Guard

With all the back-and-forth about Democratic vice presidential candidate Tim Walz’s National Guard Service, you might like to know that the origins of the U.S. National Guard can be traced back to December 1636, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony ordered the creation of three militia regiments to protect the new colony. Seen here is the first muster, in the spring of 1637, of the new force’s East Regiment, in Salem.

Thus the Bay Colony led the way in the creation of the militias eventually established by all American colonies. Some of the units ended up fighting in the Revolutionary War.

Note the Massachusetts Minute Man symbol.

‘Meditations on the lost and found.’’

“Walden Pond” (wood, plastic, foam, chiffon and bolts), by Mark Jarzombek (born 1954), in his show “Recollection,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Sept. 2. He’s an MIT-based architectural historian and artist.

He says:

“I inject playfulness and energy into construction materials I collect from from building sites. The pieces, meditations on the lost and the found, are inspired by Impressionist paintings, baroque perspectival effects and color pallets derived from Indian temples.”

Site of Henry David Thoreau's (1817-1862) cabin on Walden Pond, in Concord, Mass.

— Photo by Percival Kestreltail

Walden Pond.

— Photo by Erik Granlund

Chris Powell: When learning is optional

Scrapped mobile phones

— Photo by MikroLogika

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Schools increasingly are prohibiting students from operating or even carrying "smart phones" -- Internet-equipped telephones -- in class. Some schools are investing in special pouches in which students must lock their phones in school, being able to unlock them only with a special device made available when they are leaving.

At $25 or so each, the pouches are a significant expense, but educators find them effective at restoring students' concentration. The pouches even induce students to start talking to each other face to face.

Gov. Ned Lamont was an early advocate of banning "smart phones" in school, and while he was unable to get the General Assembly to legislate on the point, he has asked the state Education Department to draft and recommend such a policy to school superintendents and boards. It's a good idea and most school systems probably will go along with it if pressed by the Education Department.

But there is a bigger underlying problem here that no one in authority seems inclined to address.

For if students spend too much time on their "smart phones" in school, it's because they know they can afford to miss the teaching being attempted. They know they are going to be promoted from grade to grade and even graduated from high school no matter what. Learning is completely optional.

That is, even if school policy bans "smart phones," a bigger school policy will remain: social promotion. While it would be much more expensive, repealing social promotion would do much more to restore education than locking up "smart phones."

Repealing social promotion would require teachers and school administrators to enforce academic standards not just against students but also against their neglectful parents, who outnumber responsible parents in many school districts.

Like most states, Connecticut has resorted to social promotion to boost graduation rates and thereby make education look more successful even as it is failing, with the academic proficiency of students in basic subjects continuing to decline. Schools know that when uneducated students graduate they become someone else's problem -- the problem of employers and the welfare, medical, mental health, and criminal-justice systems.

The refusal to restore standards in public education may be behind the governor's recent conversion to "diversity, equity, and inclusion," the new euphemism for "affirmative action" -- racial and ethnic preferences in hiring, college admissions, and other endeavors.

Connecticut schools long have suffered an appalling gap between the educational achievement of white students and those from racial and ethnic minorities. The gap results mainly from something over which schools have no control -- the great disparity in the parenting and wealth of the homes students come from. Students who do poorly in school almost always need more attention at home, but state government declines to examine why they don't get it. More broadly, state government declines to inquire into why poverty endures and is worsening.

The state's primary policy for improving education is just to increase the compensation of educators. This has done little for education and nothing for closing the racial achievement gap, but it has kept Connecticut's biggest and most influential special interest, the teacher unions, working for the state's majority political party.

The governor's new plan to create an Office of Equity and Inclusion to diversify state government's workforce racially and in a few lesser respects indicates state government's acceptance of the racial achievement gap.

After all, if schools eliminated the gap and most high school graduates were of largely equal education across the races and ethnic groups, state government would not have to look so hard for qualified applicants from minority groups and would not have to incorporate racial and ethnic preferences into the hiring process in pursuit of diversity. Diversity and integration would occur naturally and income inequality would fall.

But the racial and ethnic gap in education generates an impoverished underclass dependent on government for sustenance, which in turn maintains government's power, size, and expense. In that respect the many who have made comfortable careers ministering to Connecticut's worsening poverty may consider the gap a great political success.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).