Vox clamantis in deserto

‘Design of darkness’

I found a dimpled spider, fat and white,

On a white heal-all, holding up a moth

Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth--

Assorted characters of death and blight

Mixed ready to begin the morning right,

Like the ingredients of a witches' broth--

A snow-drop spider, a flower like a froth,

And dead wings carried like a paper kite.

What had that flower to do with being white,

The wayside blue and innocent heal-all?

What brought the kindred spider to that height,

Then steered the white moth thither in the night?

What but design of darkness to appall?--

If design govern in a thing so small.

‘‘Design,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Chris Powell: Municipalities should be posting their most interesting records

— Photo by Michal Klajban

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Greenwich First Selectman Fred Camillo is sore at people who, he says, make lots of requests for access to town records under Connecticut’s freedom-of-information law. “Some people are abusing the system,” Camillo says, and requesting town records "has been weaponized and we’re getting harassed."

So his administration has begun posting on Greenwich’s internet site the names of all FOI requesters and the subjects of their requests.

This is perfectly legal. No one who requests access to a public record can very well object if his own request is a public record too. But Camillo’s new practice seems meant to retaliate against and embarrass requesters. It’s mistaken and almost surely will fail.

For anyone who is making FOI requests mainly to annoy town officials isn’t likely to be embarrassed in the least by publicity. To the contrary, such people probably will welcome publicity and figure that their renown will help intimidate town officials and employees in the future.

Besides, Connecticut’s FOI law now authorizes government officials to petition the Freedom of Information Commission for relief from a “vexatious requester,” a person whose requests for records are so numerous and redundant as to constitute abuse. While they are few, there are such people and the commission has taken action against some, exempting the government agency being harassed from having to respond to the requester.

So if First Selectman Camillo really thinks that any FOI requester is "abusing the system," he should identify the abuser in a complaint to the FOI Commission, whereupon the commission may call a hearing that may be as much an inconvenience to the requester as the requester’s requests are to town officials.

There’s no harm in posting FOI requests on a town’s Internet site as Greenwich is doing, but there’s not much public service in it either. Indeed, if a municipality or state agency is going to put more effort into posting records on its Internet site, many records would be of far more public interest than FOI requests.

For example, municipalities could post their payrolls as state government does. Some municipal government salaries are extraordinary but overlooked. Excessive overtime for police officers and others is often a scandal.

Municipal employee job evaluations and disciplinary records should be posted too. Those records are where some big scandals are hidden.

While teacher evaluations, alone among all government employee evaluations, long have been exempted from disclosure under state FOI law -- a testament to the influence of teacher unions and the subservience of state legislators to the worst of special interests -- nothing prevents municipalities from disclosing teacher evaluations voluntarily just as municipalities are required to disclose the evaluations of other employees.

With local journalism weakening, these days most municipal governments have little serious news coverage and few if any reporters inspect disciplinary records regularly.

Posting more records about government’s own performance would show the public far more about who is really "abusing the system." Any annoyance to government officials from this greater transparency might be offset by accountability and better management.

SLICING AWAY AT DEMOCRACY: Many people who achieve public office quickly come to realize the truth of the old saying, "To govern is to choose." French President Charles de Gaulle clarified that governing is always "to choose among disadvantages." Of course choosing can be a drag.

So some non-profit social-service groups want Connecticut to impose a special tax on telecommunications services whose revenue would be dedicated to social-service groups.

But why should cell phone or Internet users particularly pay for social services? There’s no causal relationship between telecommunications and social-service needs. It’s just that the social-service groups don’t want to have to compete for state government money as everybody else has to. With a dedicated tax their money would be guaranteed.

If choosing is restricted this way, over time the practice would slice away at democracy and insulate many rcipients of government money. Connecticut has done enough of that already.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

UBEW's diverse workforce

“We Are Power,” by Meredith Stern, in the show “Listen!”, at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, through Jan. 5.

— Image courtesy of RISD Museum.

The show has 30 historical and contemporary works on paper from the museum that curators found "urgent and powerful, directly addressing the issues [they] face while offering hope for the future.’’ The show also features reflections and poems written by the curators.

Green is good, air travel is terrible

1928 poster

Terminal lobby at Rhode Island’s Green Airport

— Photo by Antony-22

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“Once I get you up there, where the air is rarefied

We'll just glide, starry-eyed

Once I get you up there, I'll be holding you so near

You may hear all angels cheer because we're together.’’

-- From the 1958 song “Come Fly With Me,’’ with music by Jimmy Van Heusen (1913-1990) and lyrics by Sammy Cahn (1913-1993). Song was pre-airline deregulation!

Kudos to the folks at Rhode Island T.F. Green International Airport, which keeps getting honored, for being ranked by Travel + Leisure magazine as second-best airport in America (after Minneapolis-Saint Paul International Airport (“Minnesota nice’’? Sometimes.).

Green gets high marks for being, for an airport, low-key and (relatively) low stress, in part because it’s so easy to navigate. God knows that many, probably most, medium and large airports have become stress centers, serving up a mix of anxiety, anger, boredom, confusion.

Airports have become so unpleasant because of the law of unintended consequences. The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 removed federal control over fares, routes and encouraged entry of new airlines (most of which have since disappeared). That brought “the masses” into a sector whose customers had previously been mostly businesspeople and the affluent. And the nation’s population has increased from about 225 million in 1979 to about 340 million now – a hell of a lot more potential airline passengers.

Deregulation led to the fearsome hub-and-spoke system, based on using a few major airports as central connecting points, which increased passenger loads, intensified airport and air traffic congestion and eliminated many convenient nonstop flights. And if one airline dominates a hub, the lack of competition has often led to higher fares. Not exactly what the deregulators had in mind.

Another bad thing that came out of airline deregulation was that it led to the closing of airports serving small cities.

On top of that, there’s the mystery, to me, of so many Americans’ masochistic and lemming-like tendency to want to travel at the same times, which leads many people to spend as much as half the time or more on a trip amidst the hordes at airports and highways rather than at their sought destinations.

Anyway, at least the planes (even Boeing’s!) are safer these days. Think of that as you wait in lines for hours as your flights keep getting cancelled because of, say, a thunderstorm in Chicago.

One nice thing about airports, however awful they can be: They still have newsstands, which used to be everywhere but have rapidly gone away in other public places, especially since COVID erupted.

Llewellyn King: Looking back, with a sigh, at when there was more respect everywhere

Sign at Arlington National Cemetery.

Sign in São João da Barra, Brazil, saying "respect if you want to be respected".

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I can’t explain all the social and political maelstrom I have seen down through the years. But I have known times when crime was far less than it is today and political disputation, in all its forms, wasn’t a cause of violence in the population.

Here are some fragments of the changes I have seen in different places. I parade these fragments from my life because of the sense of doom, the sense that violence could break out between the political extremes in the United States; that, in effect, we haven’t seen the end of the violence of Jan. 6, 2021.

When I was a teenager in the 1950s in the Central African Federation, a long-forgotten grouping of three British colonies in central Africa — (Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe; Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia; and Nyasaland, now Malawi), the prime minister, Sir Roy Welensky, lived two miles up the road from my parents and every school day, he would pull over his big black car, a Humber Super Snipe, and give me a lift to school.

He had no chauffeur, no security, and no sense that it was needed. Those were times when society was placid — not just placid, but very placid.

When I left school at 16 and became a reporter, the prime minister would drive me into Salisbury (now Harare), the capital, which was very useful. Often he would pick up other car-less people, without regard to color, and drive them as far as the unguarded government buildings which housed his office.

There was simply no violence.

I hitch-hiked all over the federation and down to Johannesburg in the neighboring Republic of South Africa. No thought of personal safety ever crossed my mind.

It would be very unsafe and unwise to attempt that nowadays. That peacefulness went forever with the Zimbabwe war of independence, which started within a decade.

In 1960, I was in London and covering the legendary East End, an immigrant and working-class area. Peace reigned. I walked through the roughest dockside at midnight and later with no sense of fear or concern for my bodily safety. The only memory I have of being interrupted was by prostitutes, inquiring whether I needed company.

At that time, one could walk up to the prime minister’s residence at No. 10 Downing Street without being stopped. A single, unarmed policeman was all there was for security.

Now, you can’t get near No. 10. Political violence and just malicious violence is everywhere. Street crime, muggings and knife attacks are common all over London.

I was in New York during the Northeast Blackout of 1965. I had to walk across the 59th Street Bridge into Queens to make sure that the gas was turned off in a printing plant, which belonged to a partner of mine in a publishing venture. There was no looting, no threat of violence. Indeed, there was a party atmosphere and statistics show that many children were conceived during it.

By contrast, there was extensive looting and crime during the city’s major blackouts in 1977 and 2003. An ugly social indifference to each other had come into play.

I was in Rio de Janeiro in 1967 and, after having partied late into the night, I walked the backstreets of the city without fear. The last time I was in Rio in the 1990s, security personnel would prevent you from leaving your hotel after dark and caution you not to walk alone during the day.

When riots broke out in Washington and elsewhere in 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., there was massive rioting, but the anger was against property. I walked around the city during the riot, particularly on 14th Street, its epicenter. Several rioters, loaded with looted goods, suggested where it might be best for me to walk or stand to avoid being knocked over by the surging crowds.

There was still a kind of social peace, a respect of one individual for another.

Fast forward to the invasion of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. There was no such respect, either for people or the building and what it stands for, just mob anger.

About the U.S. Capitol: Back in 1968, it was easily approached and entered. You could take a taxi all the way to the entrance under the archway, either on the Senate side or the House side, and you could just walk in.

I offer these fragments from my own experience and pose the question which I can’t answer: How did we get to the state of social and criminal rage that is a reality across the globe?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Lobbying with leaves

“Green Manifesto: transformation through leaves” (video still), by Daniel Otero Torres, in his show “Sonidos del Crepúsculo (Twilight Sounds)’’, at the Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, N.H., through Oct. 6.

— Image courtesy of Currier Museum of Art.

The museum says the show honors the "unsung heroes of environmental protection" and highlights "rural and peripheral communities, power structures, and collective participation." This show includes Otero Torres's drawings on aluminum and steel structures that act as "totemic monuments" to environmental activists. This show also contains the artist's first video work.

And you thought that they had all moved to Nova Scotia

At a restaurant in Seekonk, Mass. Kitsch is one of Western Civilization’s greatest triumphs.

— Photo by Carolyn Morgan

‘Weather clerk's factory’

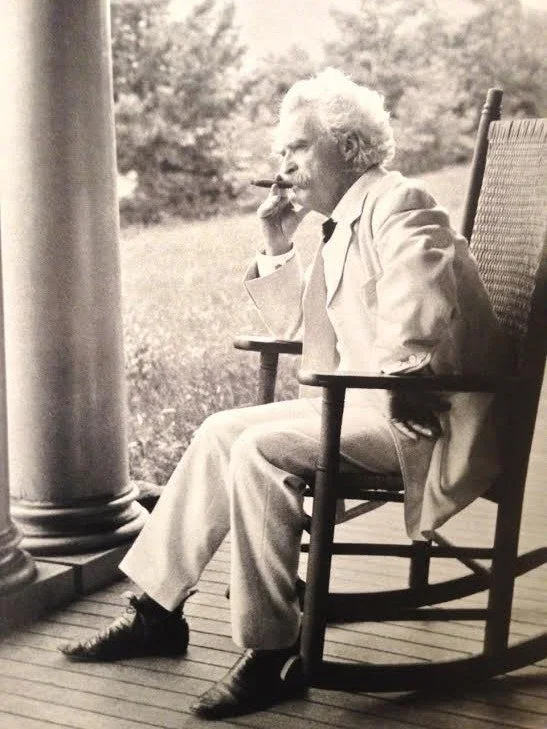

The Mark Twain House and Museum in Hartford.

“I reverently believe that the Maker who made us all makes everything in New England but the weather. I don't know who makes that, but I think it must be raw apprentices in the weather clerk's factory who experiment and learn how, in New England, for board and clothes, and then are promoted to make weather for countries that require a good article, and will take their custom elsewhere if they don't get it.’’

— Mark Twain (1835-1910), long-time resident of Hartford, Conn., who also loved his late-in-life sojourns in Dublin, N.H., where he rented a house in 1905-1906.

Mark Twain on the porch of his rented house in Dublin, N.H. He told people that Dublin had become his favorite place in the world.

Avoid us then

Daisies and other flowers in Vermont.

“Go ahead: say what you’re thinking. The garden

is not the real world. Machines

are the real world. Say frankly what any fool

could read in your face: it makes sense

to avoid us….’’

— From “Daisies,’’ by Nobel Prize-winning New England-based poet Louise Gluck (1943-2023). Here’s the whole poem.

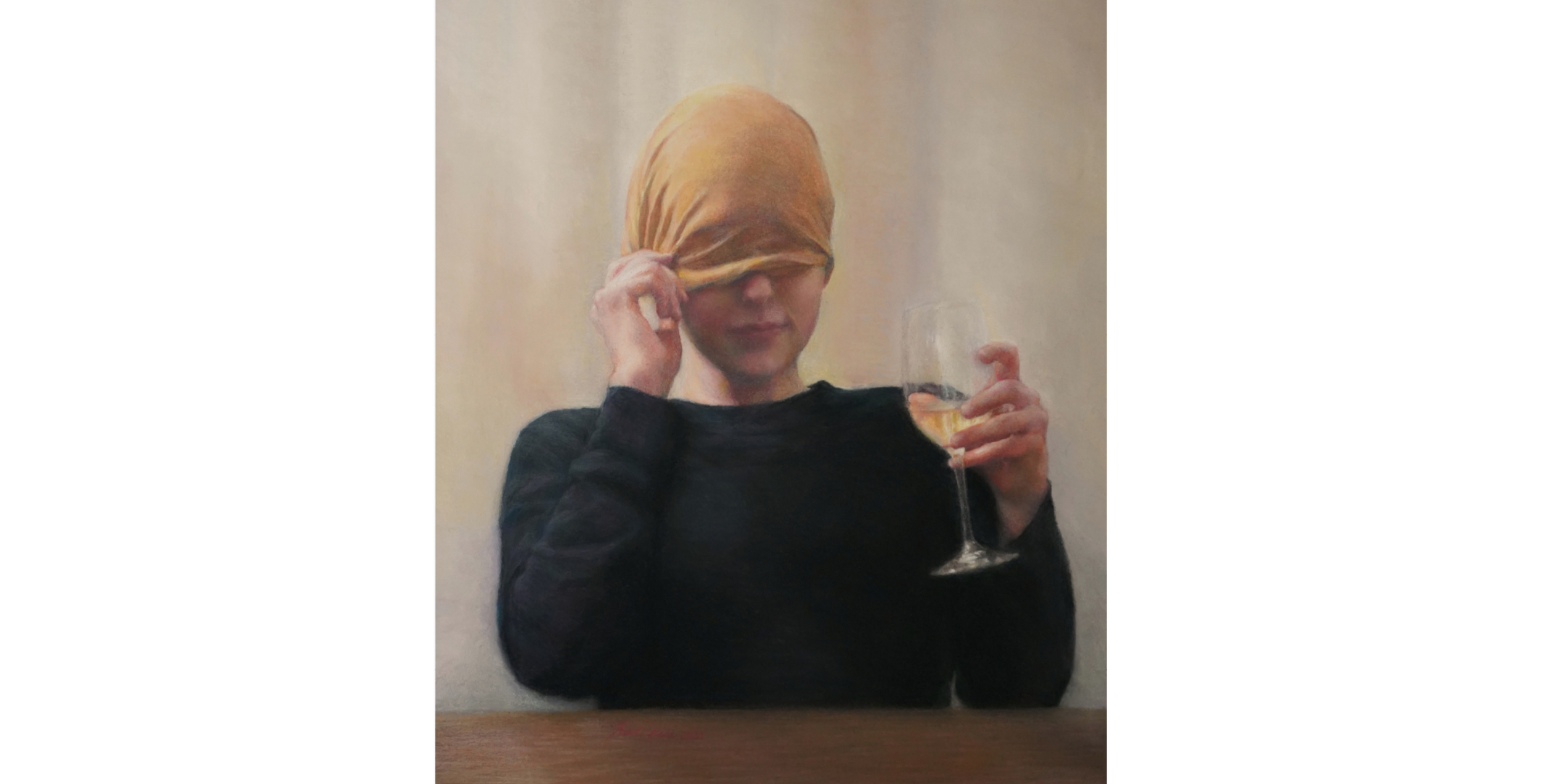

Working on her personality

“Portrait of a Young Girl” (oil on canvas), by Judith Rothschild (1921-1993), at Moss Gallery, Portland, Maine.

— Courtesy of the Estate of Judith Rothschild

Jackson Lab's big expansion

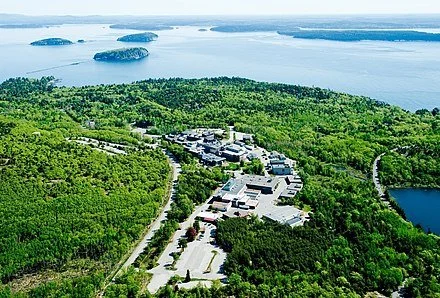

Jackson Laboratory’s campus in Bar Harbor.

Edited from a New England Council report

The Jackson Laboratory, a nonprofit biomedical-research institution in Bar Harbor, Maine, has applied to build a 20,000-square-foot expansion.

The addition will expand the lab’s Rare Disease Translational Center, including providing more space for laboratories and offices. Earlier this year, Congress allocated $8 million to construct the new facility. The project’s total cost is expected to be $32.75 million, and the addition will consist of two stories with a mechanical penthouse. Each floor will have a footprint of about 9,200 square feet, with an additional 1,688-square-foot mechanical penthouse.

The goal is to complete the project by August 2026.

The Jackson Lab says:

“Our team serves those with rare disease by accelerating the pre-clinical phase. Our vision is to provide patients with an efficient path from diagnosis to therapy, allowing them to live longer, healthier lives.’’

Rick Gorvett: As climate worsens, should homeowners self-insure?

No matter where you live, there’s a good chance the weather’s getting wilder. In just the past few weeks, tornadoes have wreaked havoc on Midwest and Southern states, and large swaths of southern Florida were flooded. Globally, 2023 was the hottest year on record.

In addition to harming life and property, weather-related catastrophes have caused the cost of homeowners insurance to spike. Premiums have risen at rates well above general inflation.

In places such as Florida that are particularly exposed to natural disasters, homeowners insurance isn’t just expensive – it’s increasingly becoming difficult to find. That has caused some homeowners to go without it entirely.

More than 6 million American homeowners don’t have homeowners insurance, according to a recent analysis from the Consumer Federation of America. That’s about one out of every 14 homeowners in the country. Collectively, they have at least US$1.6 trillion in unprotected market value. That’s a lot of risk.

As a math professor and an expert in actuarial science, which deals in assessing risks, I’ve watched the mounting homeowners insurance crisis closely.

If catastrophic weather events continue to escalate, so-called “self-insurance” – buying no insurance and paying for any losses yourself – might be the only viable option for homeowners living in disaster-prone areas.

Why risk is getting more expensive

In general, the price of risk, as reflected by an insurance premium, is a function of the risk’s potential frequency and its severity. Potential frequency means the likelihood of a loss occurring, and severity means the financial cost associated with the loss.

So, increases in the frequency or severity of risks result in higher homeowners insurance premiums. The biggest catastrophic risks affecting homeowners insurance include hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, wildfires and winter storms.

Given climate change, it’s likely that many of these catastrophes will become stronger and more common, leading to higher insurance costs. In fact, this is already happening – although how much insurance companies are pricing in the cost of climate change, and whether it’s enough, is uncertain.

If you do opt to buy homeowners insurance, as more than 92% of American homeowners do, you should comparison shop for the best price and coverage. You can do this independently or through an agent or broker.

They may not differ much in their premium prices, however, given the emerging risks. And some insurers may be unwilling to write new policies, depending on where you live. For example, State Farm and Allstate have paused their writing of new homeowners insurance policies in some disaster-prone markets in California.

Choosing to self-insure

Instead of buying homeowners insurance, you may choose to self-insure. Finance experts consider self-insurance to be a legitimate risk management strategy. But that’s only if you choose it with full knowledge of the risk exposure and financial consequences.

Self-insurance is a common component of large organizations’ overall risk strategy. For example, as many as 33% of privately employed workers nationwide are insured by employer-sponsored, self-insured group health plans. For many organizations, self-insurance is also common for workers’ compensation insurance.

For those homeowners wealthy enough to absorb a major uninsured loss, it makes sense to consider self-insurance.

Of course, there are some caveats.

First, homeowners need to be realistic about their ability to respond to a significant uninsured loss. Having a thorough knowledge of your personal financial situation – or access to a qualified financial planner – is critical.

Second, self-insurance is likely to be viable only for homeowners who own their homes outright. If there is a mortgage on the property, purchase of an insurance policy is typically required to protect the lender.

And finally, it’s important to remember that homeowners insurance is a “multi-peril” policy, which includes liability coverage for accidents. While the size of a property loss might be limited to the value of that property, liability risk is potentially unlimited.

Without homeowners insurance, potential liability exposure should be addressed in some other way – for example, through risk-control efforts such as warning signs or limiting guests on the property, or through some type of stand-alone personal liability insurance policy.

How long will the insurance crunch last?

Most insurers try to maintain stable rates and premiums. But historically, most property-liability insurance has followed a multiyear underwriting cycle. This cycle, from the standpoint of the insurer, goes from a high-premium/low-loss ratio to a low-premium/high-loss ratio, and back again.

This stems from several factors, including price competition within the insurance industry and uncertainty associated with future losses. The result is that when it comes to homeowners insurance, affordability and availability problems are often just temporary. Ultimately, supply and demand adjust, with a new market equilibrium arising as a natural part of the cycle.

Whether this will be the case for current issues in homeowners insurance depends on a number of challenges facing homeowners. There’s some reason for pessimism: Mortgage rates have recently hit their highest levels in over 20 years, and in the meantime, prices in many areas have skyrocketed.

Meanwhile, in 2023, the National Association of Realtors Housing Affordability Index reached its lowest level in almost 40 years. And the future impact of climate change on homeowners insurance losses remains uncertain at best.

Amid all this uncertainty, one thing is clear: Being, or aspiring to be, a homeowner is a real challenge these days.

Rick Gorvett is a professor of mathematics and economics at Bryant University, in Smithfield, R.I.

Rick Gorvett does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

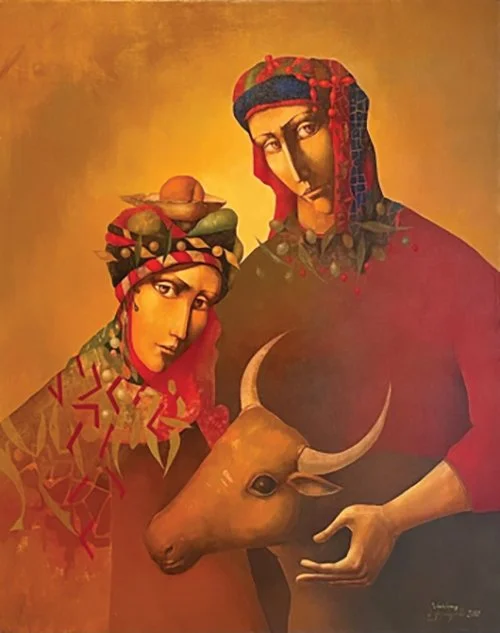

Very traditional marriage

“David and His Bride” (oil on canvas), by Vakhtang Sirunyan, in the show “Gandzaran! Notable Selections from Our Collection,’’ at the Armenian Museum of America, Watertown, Mass., through Aug. 4.

The museum explains:

“Drawing from the museum’s vaults—its ‘gandzaran’ —this exhibit showcases the development of Armenian art in the 20th and 21st centuries, from its origins in religious motifs to the Soviet period and its continuous reinterpretation among contemporary artists around the world.’’

William Morgan: It's time to retire stop signs

— Photo above by La Cara Salma

— Photos by William Morgan

Let’s face it, the days of the stop sign are over. The stop sign is an anachronism, as are simple courtesy and turn signals. Nobody pays attention to them anymore, so why do we keep them around? A stop sign can be confusing to, say, older people who might actually come to a complete stop, thereby creating a hazard and slowing the progress of all the other drivers who either ignore or do not recognize the purpose of the red metal octagon.

Stand at a busy street corner for a few minutes and count the number of cars that do not heed the stop sign. My experience of such an exercise invariably shows that a majority of motorists sail right through intersections without stopping; they might slow down for a moment, perhaps hesitating, vaguely remembering a forgotten but once ingrained habit. During a recent brunch at a restaurant on a busy Providence corner, I watched as nine out of ten cars failed to stop. The particular location is a block from an elementary school, yet the presence of crossing guard hardly seems make a dent in transgressions.

Rhode Islanders are certifiably among the nation’s worst drivers–the drivers least likely to abide by traffic rules. But I expect disobeying stop signs is a common American phenomenon–no one expects us to drive like the Swiss or the Swedes. Perhaps there are some national characteristics–anti-authoritarianism, visual impairment, stupidity–that make us want to transform a reasonable few extra seconds of pausing into a game of automotive chicken.

Maybe there’s a plot by insurance companies to raise premiums, and there’s is an army of lawyers who flood the airwaves and crowd the sides of highways with billboards asserting that they can monetize your car crash.

Eventually, I will get rear-ended by a distracted mother in her Ford Subdivision or a hedge-funder in his Mercedes Afrika Korps, or mauled by a super aggressive-looking pickup truck, the drivers all texting. Until then, I will try to retain my belief that obeying traffic rules is part of a greater social contract. Yet the failure to heed stop signs suggests a larger breakdown of society as a whole.

Like the use of cell phones while driving (illegal in my state), such actions point to a lack of connection with the world around you and your species. If you don’t make eye contact with a pedestrian, a bicyclist or another driver, you are closing down an opportunity to interact with another human, a fellow citizen. When I slow down or pull out of the way on a narrow street so that an oncoming car can pass through, I rarely get an acknowledgment, a wave of the hand, a mouthed thank you. I am just some unimportant loser in an 18-year-old Volvo who ought to give way to the driver of a hurrying urban assault vehicle on a self-important mission. My wife, however, says I am just invisible.

In neighboring Massachusetts, stop signs at dangerous intersections are getting blinking lights around their perimeters. This seems to me like the third stop light that was mandated on cars a few decades ago–and we know how effective they have been on cutting down on tailgaiting. Such well-intentioned gestures are only short-term bandages putting off the eventual removal of all these useless stop signs.

Let the all-out free-for-all begin.

William Morgan is an architectural writer based in Providence. His latest book is Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States.

From Hitler to Trump, the thirst for a dictator to quash perceived foes

A projected image of Trump, from behind a bulletproof shield, delivering his speech on Jan. 6, 2021, urging his followers, many of them violent, to march on the Capitol to overturn the election he lost.

And a hearty sieg heil!

Nazi rally in Nuremberg in 1934.

“History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.’’

— Quote attributed to Mark Twain (1835-1910)

You’ll hear some rhyming this week at the Republican National Convention, in Milwaukee.

Neo-fascist political commentator Nick Fuentes, in this logo, made contemporary use of the phrase “America First,’’ the isolationist movement before Pearl Harbor that included pro-Nazis, such as Charles Lindberg. He cited Trump and his presidency as an inspiration for his show.

Thoughts about beaches

Nauset Beach on Cape Cod, with eroding bluffs.

Popham Beach, Maine, on an evening in July.

Photo by Dirk Ingo Franke

View of Nantasket Beach, in Hull, Mass., in 1879, when it was a very popular resort for Bostonians.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s Digital Diary, in GoLocal24.com

“Objects on the beach, whether men or inanimate things, look not only exceedingly grotesque, but much larger and more wonderful than they really are.’’

-- Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) in Cape Cod, published in 1865.

Sandy beaches, with dunes or bluffs behind, stony beaches and these days even disappearing beaches, draw us. I’ve lived near most major varieties.

Beaches invite long walks, and offer a wide-open view to the horizon, which we need in our all-too-indoors world. And they’re the best places for kite flying because they’re usually breezy; too bad that you don’t see as much kite flying these days. I mention in passing beaches as venues for sex. Bad manners.

They also offer surprises: The waves constantly bring in different things to look at – some beautiful, some hideous – maybe, if you’re unlucky, even a human body. Every day walking on a beach brings different revelations, especially when it’s stormy. You’ll find such treasures as colorful sea glass -- physically and chemically weathered glass found on salt-water beaches. There used to be a lot more before plastic (made from petrochemicals) took over much of the container business. Plastic bottles, etc., turn into microplastics that present a range of environmental woes.

Then there are skate-egg cases. But there are fewer interesting shells these days and, it seems, less driftwood. And far fewer horseshoe crab shells, in part because they’re being fished out for their blood for use in medical applications. You probably know that they aren’t real crabs, by the way, but, rather, related to spiders and scorpions. Creepy?

Then there are various kinds of seaweed, some of which are edible, and useful for other purposes, too, though they draw insects, some biting, to the beach, and can have a rank smell.

High summer on beaches thronged with people can be problematic. Best to go before Memorial Day and/or after Labor Day. Then you can hear the birds and the wind more than the yelps of vacationers; you’re more likely to avoid the screech of transitorily popular music, or cutting your feet on a beer can, and, if you’re casting for fish, less likely to catch someone in the eye.

I’ve been thinking a bit more about beaches these days because the last close relatives I’ve had on Cape Cod are selling their house in a village where we’ve had ancestors (many of them Quakers) since the 17th Century. There’s a beautiful sandy beach close by (though it’s eroding at an accelerating rate because of seas elevated by global-warming) that brought us many fine memories. The clean water is warm from late June to late September – in the 70s (F) – and there were/are graceful sand dunes we used to roll down as kids.

My paternal and laconic grandfather, who lived in West Falmouth after retirement, used to call the entire Cape “The Beach.’’

Hydrangeas bloom for several weeks.

— Photo by EoinMahon

Summer bloom bursts

How nice now to enjoy such spectacular blossoming of hydrangeas as distraction from so much grim news. Of course, most news in the media is grim: “If it bleeds it leads’’. Gotta turn it off now and then.

The mild and wet winter is being given much of the credit for the particularly vivid colors of these acid-and-coastal-loving bushes this summer, which can make walking around so cheery and make you forget that the most colorful time of the year is late spring and October, not mid-summer. There’s a great Robert Frost poem called “The Oven Bird,’’ that deals with this.

Now a lot of the blooms, which come in a range of colors, are fading.

‘Cancel space’

The Bearcamp River in South Tamworth, N.H., on the southern edge of the White Mountains

“No matter how tightly the body may be chained to the wheel of daily duties, the spirit is free, if it so pleases, to cancel space and to bear itself away from noise and vexation into the secret places of the mountains.’’

— Frank Bolles (1856-1894), writer and lawyer, in his book At the North of Beaucamp Water: Chronicles of a Stroller in New England

Inspired by Mid-Century Modern design

“Gioco Palla” (diptych) (oil on canvas), by Boston-based painter Susan Morrison-Dyke, in her show “A Roll of the Dice,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through July 28.

She says:

“Finding my inspiration in the sleek abstraction of Mid-Century Modern design, the inventiveness of cubism and the authenticity of primitive and ancient art, I often rely on intuition and spontaneity to guide my artistic process.’’

The gallery says:

“Morrison-Dyke’s vibrant abstract paintings juxtapose formal blocks of color with playfully drawn interpretations of natural and stylized forms.

“The improvisational quality of the work results from a decisive design structure, which underlies the artist’s use of inventive and painterly abstractions.’’

The Chapel at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, designed by Eero Saarinen, is a classic example of Mid-Century Modern design. It was opened in 1956.

— Photo by Daderot

Chris Powell: Extending medical insurance to illegal immigrants draws in more of them

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut's nullification of federal immigration law proceeded this month as state government extended its welfare system's medical insurance to illegal immigrant children by three years, from 12 and under to 15 and under. The children being added will be able to keep their state coverage until they turn 19 -- and maybe, as seems likely, by the time they turn 19 Connecticut will have extended eligibility to a higher age.

Such gradualism is how Gov. Ned Lamont and the Democratic majority in the General Assembly have been handling the issue for years now. They have been maintaining both that decency requires covering all illegal immigrant children and -- in contradiction -- that the state can afford to cover only a few thousand more every year. This gradualism obscures the budgetary and nullification issues enough that most people don't notice and make a fuss about them.

While the policy being pursued by state government may make political sense, it is still mistaken. Its logic is that Connecticut somehow can afford to lift all of Central America and much of the rest of the world out of poverty in the next decade, and it encourages more people to violate federal immigration law.

Advocates of extending the medical insurance to more illegal immigrant children note that even without such insurance Connecticut's hospitals will always have to treat illegal immigrant children when they come to emergency rooms with urgent conditions, and that when such patients or their guardians don't pay, hospitals essentially will transfer the expense to state government and patients who do pay for themselves.

But this rationale does not acknowledge that providing medical insurance to illegal immigrant children rewards and incentivizes illegal immigration to Connecticut and that if the state did not extend the insurance, the parents or guardians of the children being covered might relocate to other states providing coverage. It's not as if illegal immigrants in the United States have no choice but to live in Connecticut. Like everyone else they may look for the place where they are treated best.

While Governor Lamont supported the latest extension of insurance, when it took effect the other day he implied that he had some reservations about it, saying it should be accompanied by "comprehensive immigration reform." But of course it has not been accompanied by "comprehensive immigration reform," and the governor didn't specify what "comprehensive immigration reform" is.

Is it mass amnesty, making all illegal immigrants legal, as many other Democrats want?

Is it deporting all 12 million or so illegal immigrants estimated to be in the country, the objective that has been proclaimed by presidential candidate Donald Trump without an explanation of how the logistical difficulties would be met?

Is it to continue having open borders most of the time, as advocated by Connecticut U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy via the dishonest "compromise" legislation he proposed in February with Sens. James Lankford (R.-Okla.), and Kyrsten Sinema, the former Democrat and now nominal independent from Arizona?

In any case the millions of illegal and unvetted immigrants who have entered the country since President Biden took office are not an accident but policy, a policy of devaluing citizenship and hastening change in the country's demographics and its democratic and secular culture. Extending medical insurance to illegal immigrants -- on top of driver's licenses and other government identification documents, housing, and food subsidies -- is part of that policy. So is forbidding state and municipal police from assisting federal immigration agents, as Connecticut forbids them, thereby making itself a "sanctuary state."

If illegal immigration is never to be simply stopped and immigration law simply enforced, the country won't be a country anymore.

The United States long has welcomed immigration and should continue to do so. But immigration must be limited to what the country can assimilate in normal circumstances. A desperate national housing shortage, strain on hospitals, and schools overwhelmed with students who don't speak English signify the obliviousness to illegal immigration by both the federal government and state government.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

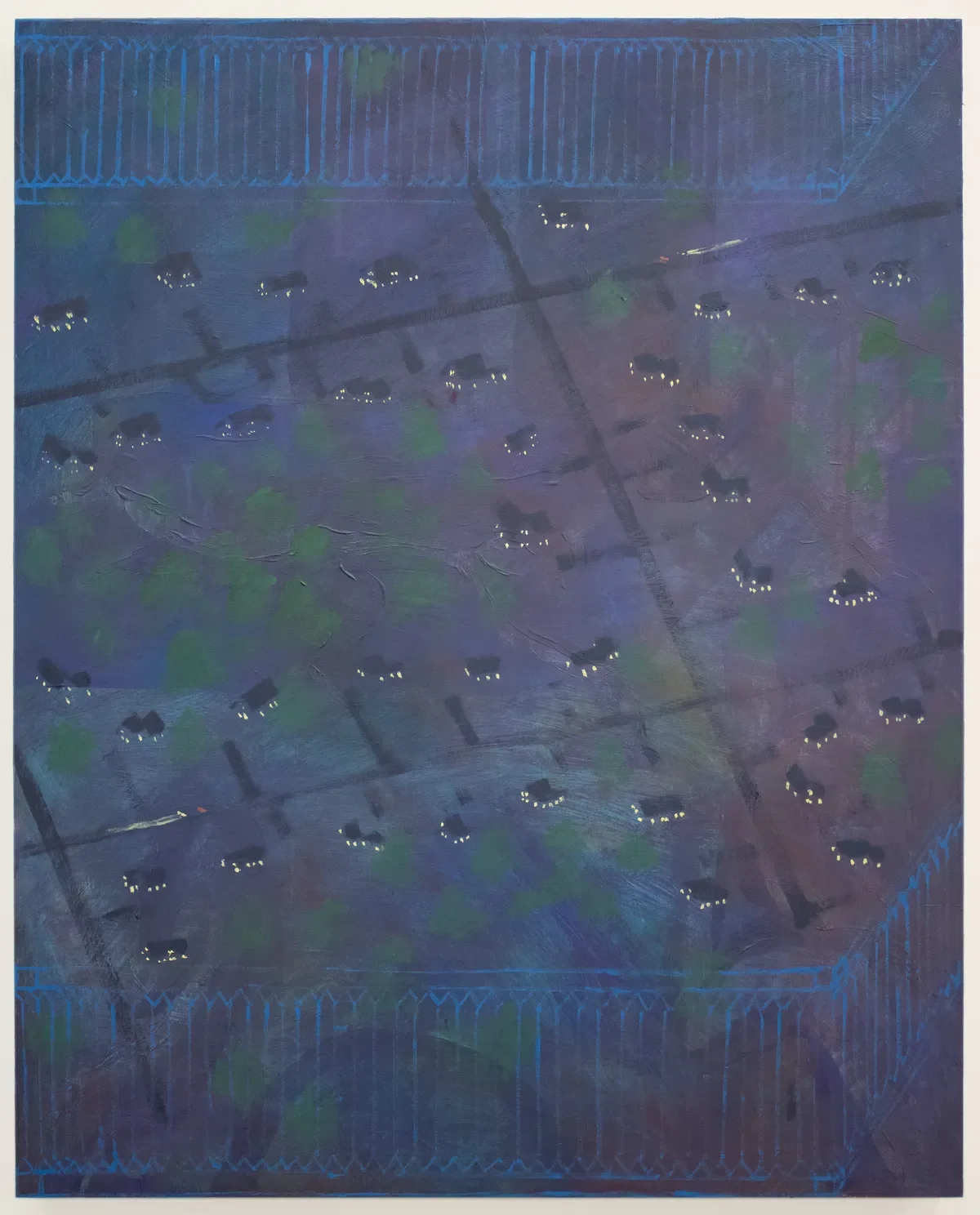

‘Between the literal and abstract’

“Tokyo Moose” (acrylic and oil on canvas), by Patrick McCay, in his show “And She Feeds You Tea and Oranges That Come All the Way From China,’’ at Whistler House Museum of Art, Lowell, Mass.

The museum says:

“Patrick McCay’s work occupies the space between the literal and abstract. Skillfully orchestrated colors pepper the expressive surfaces of chosen icons. Grounded in a scaffold of remarkable drawings and an immediacy of gestural brushstrokes, he tempts and teases with a visual theatricality, adding the dignity of the ‘unknown’ to that which is all too well ‘known.’ McCay focuses his visual explorations within the imposed contours and attentive challenge of thematic expression.’’