Poisoned Ivy?

The Harvard Lampoon Building, also known as the Lampoon Castle, in Cambridge. Prepare to see The Lampoon, Harvard College’s humor magazine, take on Harvard’s problems with Congress.

— Photo by Beyond My Ken

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

In Schenck v. United States (1919), U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. famously wrote of free speech that “no one has the right to {falsely} shout ‘fire’ in a crowded theater.’’

What about shouting “kill all the ----"?

There was something creepy about the congressional grandstanding (mostly by Republicans, of course) in grilling the presidents of Harvard, MIT and the University of Pennsylvania about anti-Semitism, alleged and real, on their elite campuses. Of course those leaders’ robotic and evasive, or at least equivocal, responses, crafted by a law firm, didn’t do them any good in facing those on Capitol Hill set on appealing to their always-angry-and-envious base and funders by sticking it to the trio, portrayed as Ivy-covered swells.

The authoritarian-minded inquisitors were basically telling the private universities’ leaders how to run their institutions. But even small colleges, let alone the big elite ones above, are complex enough to be compared to little countries, with sometimes warring constituencies – students, trustees, faculty, funders (including very rich and sometimes arrogant and bossy donors, more and more of whom are oft-amoral hedge fund and private-equity moguls), and residents of the schools’ host communities. These institutions can’t be run as dictatorships.

Further complicating things is that colleges and universities are, more than most other parts of American society, supposed to be dedicated to freedom of speech and inquiry. That’s bound to lead to angry encounters. Finally, universities are increasingly ethnically and otherwise diverse, thus leading to tensions between, say, people of Jewish and Palestinian backgrounds on campuses.

As for speech codes for students: They may make things more toxic by bottling up anger. But I’d leave decisions on codes to each university and its officials’ sense of the danger of violence on their own campuses. And if students don’t like the codes, they can transfer to a school more suitable for their feelings and opinions.

Of course, the threat to yank federal money always hangs over congressional hearings. But we should bear in mind that colleges and universities get federal money for good reasons -- to educate future leaders and other citizens, to underwrite scientific and other research and otherwise enrich society. In short, for the national self-interest.

Thus while I think the three presidents above generally did a bad job in explaining their universities’ evasive “official” positions on confronting anti-Semitism in the current fraught climate, I have some sympathy for them, even if they are trained, as are many leaders dealing with crises, to prevaricate.

Meanwhile, now that Harvard President Claudine Gay has been raked over the coals in Congress, her career in the distant past is being exhumed, raising allegations she’s a plagiarist, and certainly some of her scholarly work has that aroma. So I wouldn’t be surprised if she’s soon no longer leader of America’s richest university. Once you’re in hot water for one problem, you’re apt to find yourself in it for something else as your enemies continue digging.

An inventor’s etching

“Hairy Hare” (zinc etching, mixed media), by Dan Welden, in his show “Dan Welden: Solo 100,” at Mitchell • Giddings Fine Arts, Brattleboro, Vt., through Jan. 14.

The gallery says the show celebrates “paintings and prints by artist Dan Welden, inventor of the solarplate etching process, with his milestone 100th solo exhibit. Also featured, ‘masterworks,’ hand pulled impressions of current and past masters collaborating with Welden, including Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Kiki Smith, Eric Fischl, Roy Nicholson and others.

The Brattleboro Retreat treats mental-health disorders and drug addiction. It was established as the Vermont Asylum for the Insane in 1834. New England has many private facilities dealing with mental illness and drug addition.

Photo by Beyond My Ken

The glory of 'gravy'

“Gravy is what Italian-Americans call tomato sauce, the three-hour kind with enough meat to feed a small country. My mother makes a huge pot of it every Sunday. It isn't so much about cooking as it is about connecting with her heritage. She likes knowing that generations of her maternal ancestors spent their Sunday mornings stirring what they called 'ragu' in their own kitchens. Even when we ate Sunday dinners at Nonna's, my mother made her own gravy before we went. She'd give half the pot to me to bring to the city, and before the end of the week we had each used up our share for lasagne, sausage-and-pepper sandwiches, baked stuffed peppers, and veal parmigiana.”

― Nancy Verde Barr (born 1944) in Last Bite. The food expert is a native of Providence, famous for its large Italian-American community and eateries.

‘Winteractive’ whale in Boston

Boston behemoth

From The Boston Guardian:

“A massive whale sculpture has received final approval for installation in {Boston’s} Downtown Crossing, promising to interact with visitors through responsive light and sounds….

“Hailing from Quebec, the 60-foot sculpture is the first component of the ‘Winteractive’ public art series sponsored by the Downtown Business Improvement District (BID)….

“The completed art series will form a linear path through the Downtown with a focus on lights, interactive exhibitions and play features that can occupy younger audiences. In addition to Downtown Crossing, the BID also hopes to bring visitors to Chinatown, the financial district, Government Center and the theater district.’’

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

‘Layers of time’

“Facade” (hand-woven and Jacquard-woven fabric, knitting, paint), by Maris Van Vlack, in the show “The Blu of Distance,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, Jan. 3-Jan. 28

The gallery explains:

"‘The Blue of Distance’ features a series of textile objects that combine weaving, knitting, and paint to create layered and dimensional images referencing architecture, family history, and abandoned landscapes.

“The imagery is drawn from an archive of family photographs, using layering of material as a process through which to explore the way that landscapes evolve overtime through geological and historical events. Each of these pieces function as a window through which to see layers of time and memory, and depict spaces that exist between the past and the present.’’

Seal of the New England Historic Genealogical Society

Bella DeVaan: Billionaires on your Christmas list

“The Worship of Mammon” (1909), by Evelyn De Morgan

Via OtherWords.org

It’s high giving season in America. From Angel Trees and red buckets to year-end appeals, nonprofits and charities receive more donations during the five week holiday stretch than any other on the calendar.

Millions of people whose incomes are too low to take advantage of charitable tax deductions are still moved by the holiday spirit to give generously.

For Americans with enough income to itemize — less than 10 percent of the country’s population — the tax benefits of giving to charity can encourage generosity. For over a century, our country has used tax deductions to publicly subsidize charitable donations because of the promise that they can help fund a better world.

Yet there’s a pernicious trend in year-end giving: It’s more and more dominated by the extremely wealthy.

The share of regular people giving to charity has decreased, slipping below 50 percent of households for the first time in 2018. The share of how much regular people give to charity consistently hovers around 2 percent of annual disposable income.

Meanwhile, mega-philanthropy has been increasing — even as these mega-philanthropists keep getting richer. This gargantuan giving might sound like good news. But the rise of “top-heavy philanthropy” correlates with a decline in household buying power and a staggering increase in inequality.

The extremely wealthy don’t give the way regular people do. You might donate directly to a local food bank, the Red Cross, or another charity that directly serves people in need. But the very richest are more likely to give first to intermediaries whose charitable impact is a lot murkier.

At this point, 41 cents of every dollar donated to charity — over $130 billion in 2022 — flows into private foundations and donor-advised funds, known as charitable intermediaries. The donors can take a big tax break immediately, while those intermediaries promise to distribute the donations to working charities in the future.

Private foundations are required to disburse just 5 percent of their assets each year — and donor-advised funds face no payout or transparency requirements. This creates a massive lag in money reaching organizations with urgent needs.

That means we’re losing out on tax dollars that might support schools, jobs, public programs, or the environment for “charitable” contributions that could sit warehoused in private foundations or donor advised funds for years. My colleagues and I at the Institute for Policy Studies estimate that the costs in tax revenue likely add up to several hundreds of billions of dollars each year.

In other words: The average taxpayer’s holiday generosity extends, unwittingly, to subsidizing the ultra-wealthy.

Many American workers — including firefighters, teachers, and nurses — already pay a higher tax rate than American billionaires. They take home less income in a year, too, than average CEOs of large companies make in a few hours. The idea of these workers subsidizing billionaire philanthropy — which may or not support real charities, and certainly not at an acceptable pace — feels wrong.

This holiday season, we should demand a world in which we all get to define our common good — where the wealthiest cede power to the charities, causes, and people who they claim to support and who enabled their success in the first place.

That means restructuring philanthropy so those foundations and DAFs have to quickly distribute funds to urgent causes. It also means making our tax code fairer and funding public investments so fewer Americans need to rely on charity in the first place.

Let’s kick billionaires off the nice list.

Bella DeVaan is a researcher at the Institute for Policy Studies and co-author of the IPS report “The True Cost of Billionaire Philanthropy’’.

Colleen Cronin: Monitoring the health of a bay by seagrasses

Zostera marina – the most abundant seagrass species in the Northern Hemisphere.

Evolution of seagrass, showing the progression onto land from marine origins, the diversification of land plants and the subsequent return to the sea by the seagrasses.

Text by Colleen Cronin for ecoRI News

There are many ways to understand the health of Narragansett Bay. Scientists monitor its bacteria and nutrient levels, its temperature, and the populations of its sea creatures.

But there is another indicator, lying below the surface, recognized by the Environmental Protection Agency and tracked by the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program (NBEP), that can also help explain the complicated condition of Rhode Island’s marine waters.

Seagrasses that make up the “forest beneath the sea” shelter the sea’s young, provide food for its inhabitants, stabilize sediment, and even absorb carbon, according to NBEP staff scientist Courtney Schmidt. But their growth can also sound the alarm on the overall health of the water.

In Rhode Island, the two prominent types of seagrasses are called widgeon grass and eelgrass. The latter is the most common.

“We don’t have a big historical record of seagrass,” Schmidt said. “That isn’t to say it wasn’t there, it’s just that we weren’t writing it down.”

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Llewellyn King: Christmas sweeps up the world

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I am an oddball. I like to work on Christmas.

I don’t know how it is now, but when I was younger and worked for newspapers, variously in Africa, Britain and the United States, I always volunteered to work over the holiday and loved it. There was a special Christmas camaraderie, often more than a little nipping at the eggnog, and the joy to know that senior staff weren’t around — and, especially, to know that they weren’t needed. We, the juniors, could do it.

When you were unimportant otherwise, being in charge of a daily newspaper was the kind of Christmas gift one savored. It was a case of being news editor, city editor or chief correspondent for a day.

The senior editors were gone, and the junior staff had the run of the proceedings. Lovely fun, it was.

But not every worker is happy to labor on the great day. Consider the parish priest.

Once, I stayed with my wife, Linda Gasparello, at The Homestead, the grand hotel in Hot Springs, Va., where affluent Washingtonians have been spending Christmas since the 1800s.

Having feasted happily but unwisely on Christmas dinner in the hotel’s baronial dining room, we felt the need for a little drive and perhaps a walk. We fetched up at The Inn at Gristmill Square, in Warm Springs. The town abuts the hotel’s 2,300 acres and is a delightful contrast, small and cozy.

At the bar was the local Episcopal priest. He was enjoying a little bottled Christmas cheer. Together, we had some more of what had brought him to his relaxed state and, looking dolefully at me, he said, “I love my job. I love my parishioners. But Christmas is so hard on a parish priest, that is why I am here with my friend,” he indicated the bartender.

He explained that apart from the additional services, he was expected to call on many families, attend many parties, eat lunches and dinners, and visit the sick and attend the everyday pastoral work of his office. The poor father was exhausted and enjoying Christmas in his private way, far from the madding crowd.

Clearly, this was nothing like the lark of working on newspapers at Christmas. But we shared more cheer, and he told me of how the real Christmas for him was in his daily pastoral work. He also liked working on Christmas, just that his lasted all year and got a bit hectic toward the 25th of December.

I marvel at Christmas. How it grips the whole world. How transcendental it is. How it sweeps up denominations. How Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and animists get into the spirit of it.

Also, I marvel at how Christmas has been modified globally to fit the Northern European tradition, with snow and mistletoe and songs that often have no religious relationship — like “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” or “White Christmas.”

My mother — who, like me, grew up in Africa — was against what she saw as the cultural appropriation of Christmas by the snowy European influence. She insisted on covering the house in ferns and other greenery, which she cut and hung on the 24th of December. Not an hour earlier. The 12 days of Christmas began for her on Christmas Eve and extended to Twelfth Night. Decorating earlier was heresy.

In vain, I pleaded for cotton wool snow, even though there was no snow in Bethlehem, and told her there was no greenery in the desert.

“Good King Wenceslas” was, it is believed, the Duke of Bohemia, now the Czech Republic. But to us in Africa, in the summer in the Southern Hemisphere, the snow lay deep and crisp and even in our imaginations.

That is the miracle of Christmas. It is for everyone, celebrated in its own way across the continents, inside and outside of Christendom.

Christmas is the world’s happy place. Enjoy!

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy consultant. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

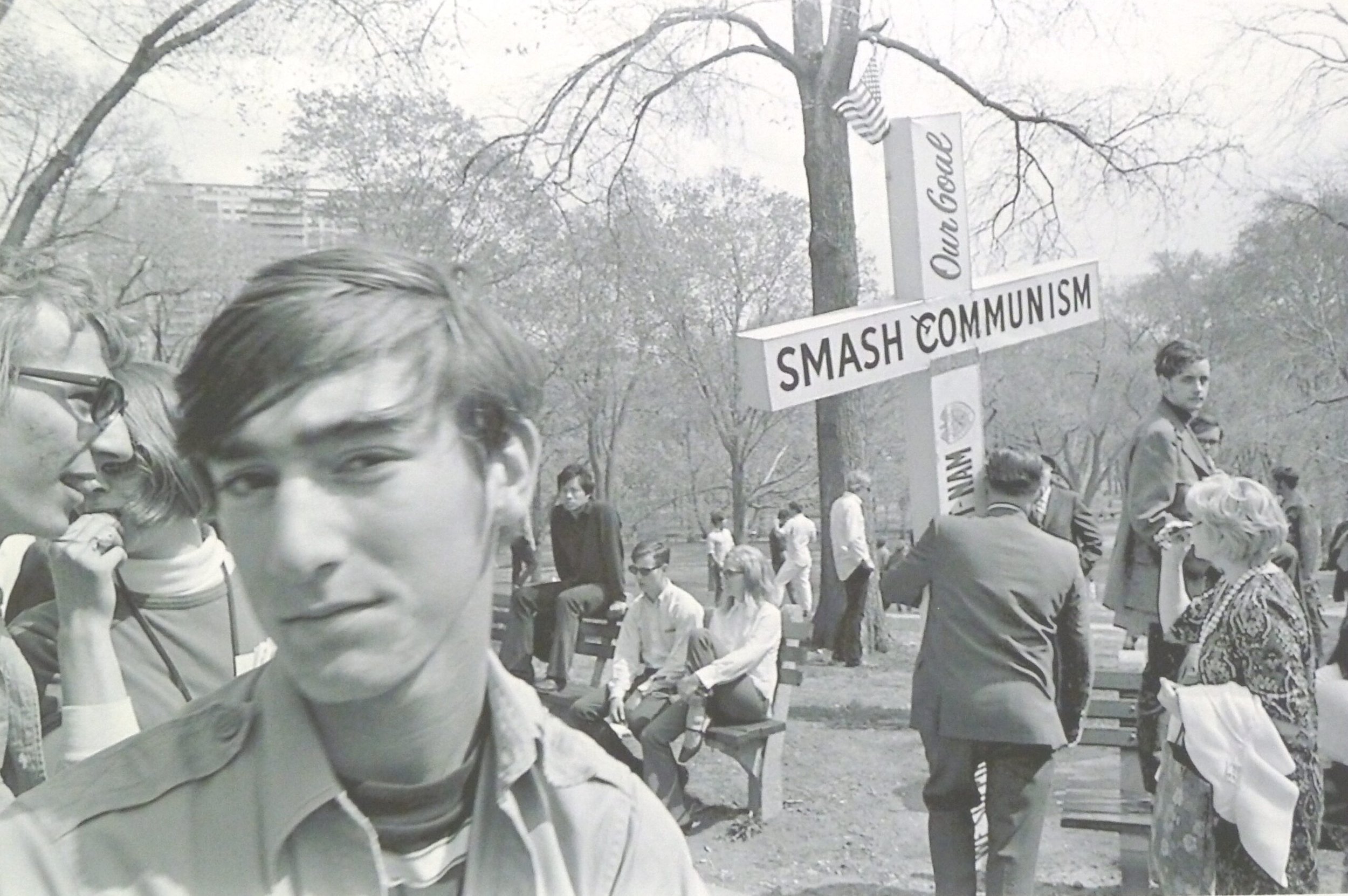

In the protest age

“Smash Communism: Boston Common 1969),’’ by Southborough, Mass.-based multi-disciplinary artist Joe Landry, in the show “Capital Vice: Politics of the Seven Deadly Sins,’’ at the Fitchburg (Mass.) Art Museum, through Jan. 14.

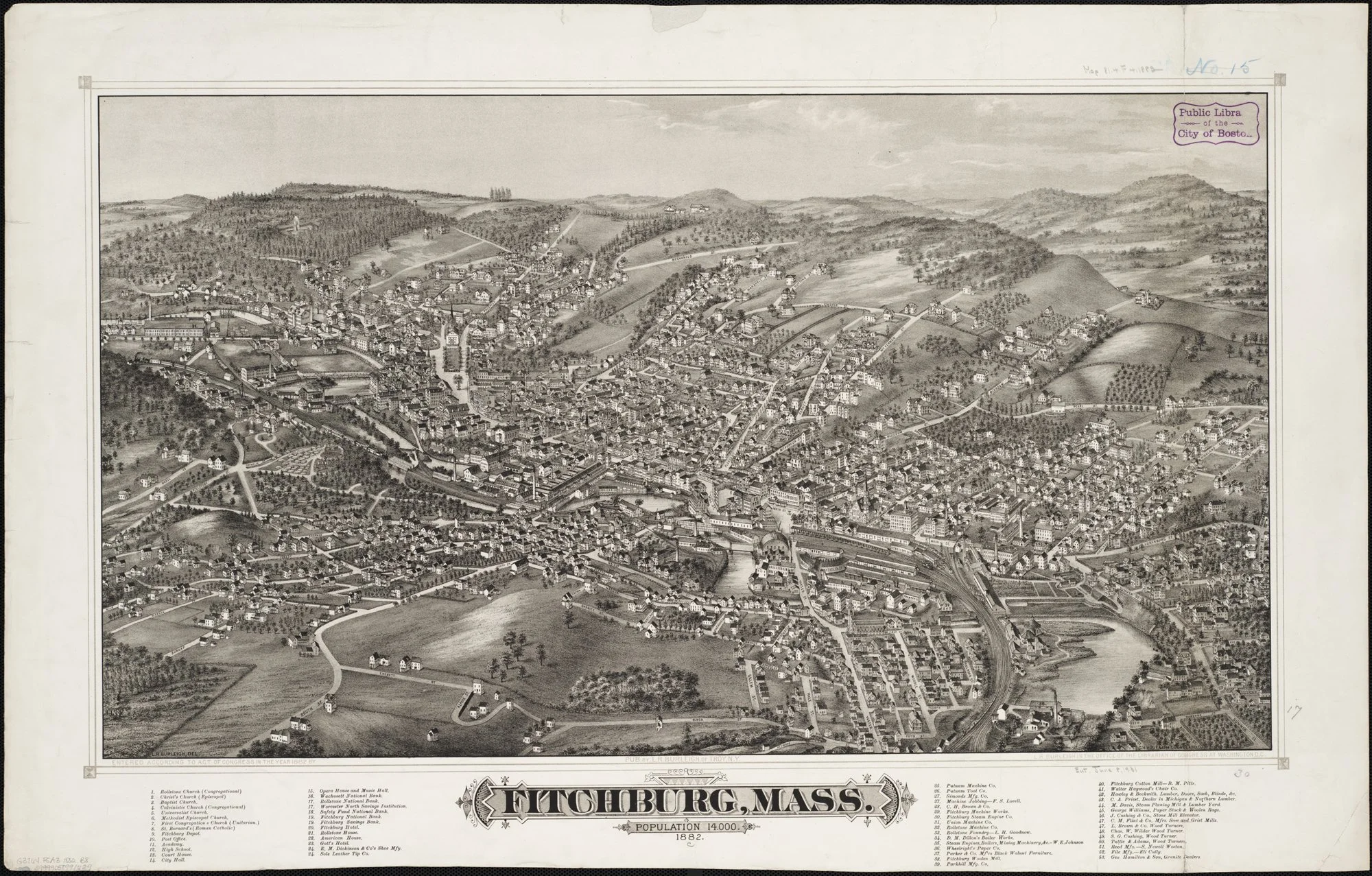

Fitchburg in 1882, when it was a thriving diversified manufacturing center.

In the center of Southborough.

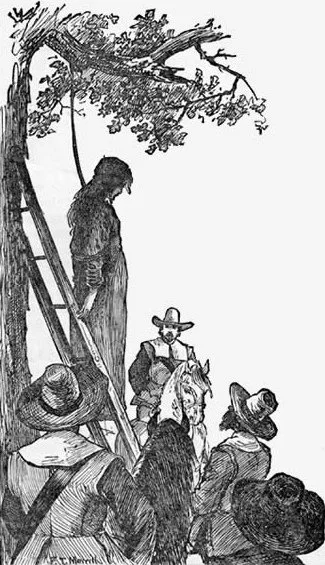

This illustration depicts the execution of Ann Hibbins on Boston Common for witchcraft in 1656.

Chris Powell: Adios school integration, and college is way overpriced

Capitol Community College, in Hartford.

“The Problem We All Live With” (1964 oil) painting), by Norman Rockwell, dramatizes efforts to integrate Southern schools in the face of intense racism. U.S. marshals are escorting the little girl to a newly integrated school.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

For decades, even before the Connecticut Supreme Court decision in the school-integration case of Sheff v. O'Neill,. 27 years ago, educators have been telling the state that racial integration in education is crucial to better student performance, especially for children from minority groups. In response, Connecticut built and operated dozens of regional schools at a cost of billions of dollars to induce minority students from the cities and white students from the suburbs to mix voluntarily.

While the regional schools have moved thousands of students around, they have produced little integration, particularly in Hartford, which was the center of the Sheff case. Student performance throughout the state has continued to decline. But the political correctness of it all has produced high-paying jobs for many educators and has made them feel better about themselves.

Whereupon last week the state community college system repudiated racial integration in education without anyone noticing it.

The system announced a partnership with Morehouse College, in Atlanta, through which students of color who graduate from Capital Community College, in Hartford, in two years with an academic average of at least 2.7 will be guaranteed admission to Morehouse as juniors on their way to a four-year degree.

Morehouse is a prestigious "historically Black" institution, and according to Connecticut's Hearst newspapers, state community college officials said "studies have shown that Black students who enroll in historically Black colleges and universities are more likely to earn their degrees and have more income than those who attend non-HBCU institutions."

Surprise! Racial integration is not such a boon in education after all.

"HBCUs like Morehouse College inherently believe in the success of their students," community college system President John Maduko said, implying that other schools couldn't care less about how their students do.

So having long strived to integrate its students in primary education, Connecticut now will strive to resegregate them when they get to higher education.

The irony passed without comment from the state's education bureaucracy and the rest of state government. Have those billions spent on regional schools been wasted? Who cares? Now let's cost people billions more by making them all buy electric cars.

Meanwhile, the even more expensive failure of higher education is getting less notice than the failure of lower education.

Bloomberg News reported last month that changes to the federal college student loan program made since President Biden took office have facilitated forgiveness of more than $127 billion in debt, which has been transferred to taxpayers.

The problem of student loan debt is presented as a matter of the heavy burden that prevents borrowers from advancing to homeownership and family formation.

But this is only a subsidiary scandal. The bigger scandal is the grotesque overpricing of higher education. If higher education was worth what is charged for it, millions of young people wouldn't be stuck with heavy debt for so long. They would get jobs paying them enough so that they easily could discharge their debt soon after graduating.

The loan system itself is largely responsible for inflating the cost of higher education. The more money is available, the more colleges and universities will absorb it, as by establishing courses and degrees that bestow few job skills.

A 2014 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that many college graduates end up in jobs that don't require college education. A study a year earlier by the Center for College Affordability and Productivity reported that there were 46% more college graduates in the U.S. workforce than jobs requiring a college degree.

College grads often earn more than other people. But is this because of greater knowledge and skills or because of the credentialism that higher education has infected society with?

Nothing has been done about this problem, since college loans are less of a benefit to students than to educators and college administrators, the ultimate recipients of the money and a pernicious influence on politics.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

'Beauty of decay'

Video still from the show “Impermanence III,” by Connecticut-based artist Miller Opie, at Fountain Street Fine Art, Boston, through Jan. 14.

She explains:

“I started making art to explore a very personal physical experience that started over ten years ago. After several years of surgeries to rebuild my jawbone that was being destroyed by benign tumors, I create art to intimately explore beauty, mortality, and rejuvenation. As my practice has progressed, I have found that there is great beauty in aging, evolving and even in decay. These themes have led me to explore the idea of ‘Impermanence”’ while at an artist residency in France last year. This film shows the continuation of the ‘Impermanence’ concept in which I created a sculpture of seagrasses and jute at another recent artist residency. I wove the seagrasses with jute into small basket forms that float in the ocean water, seeming to rejuvenate and come back to life. The result is a meditation on nature, life, and its impermanence.”

Party poopers

Charlotte Perkins Gilman

“No one who sets out to make the world better should expect people to enjoy it. All history shows what happens to would-be improvers.’’

— Charlotte Perkins Graham (1860-1935), a Hartford, Conn., native, was an author and social activist.]\

xxx

“You've got that kiss, that kiss that warms

That makes reformers reform reforms

'Cause you've got that thing, that certain thing.’'

— From the song “You’ve Got That Thing,’’ by Cole Porter (1891-1964) , who was educated in New England.

Techno ‘ghosts’

“Free Standard #2, by Boston-based multimedia artist Andrew Neumann, in his show “Free Standards,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Dec. 30.

He explains:

“‘Free Standards’ is a series of sculptures that explore the cinematic apparatus, while excluding the actual camera itself. Coming from a technical filmmaking background, the technician is offered a bevy of components to help the cinematic apparatus function in a myriad of ways. For these works, I have stripped away the camera itself, and let these pieces act as ghosts, so to speak….”

A heavyweight character

Rocky Marciano (1923-1969) in about 1953. He was heavyweight boxing champion of the world in 1952-1956 and retired undefeated. He grew up in the old shoemaking city of Brockton, Mass.

Main Street in Brockton in the early 20th Century.

”I was on a plane with him one time when he was the champion. And of course coming from Massachusetts, Rocky Marciano was my favorite. You play your character and it isn't right to step out of it. You have to stay in that character….Rocky Marciano had such guts and heart. He was something special.’’

— Robert Goulet (1933-2007), Canadian-American singer and actor. He was a native of Lawrence, Mass.

Traffic traumas

Carving showing the warrior Abhimanyu enteringa a labyrinth in the Hoysaleswara temple, Halebidu, India

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’ in GoLocal24.com

On the west-bound closing on Route 195’s Washington Bridge: Once more fear and chaos triumph.

Meanwhile, I know that highway engineering can be difficult, especially in densely populated areas, but surely the Rhode Island Department of Transportation can make it easier to navigate the new rotary on the east side of the always-being-rebuilt Henderson Bridge project between Providence’s East Side and that speed-trap capital called East Providence. The current signage sends many people in circles or facing the peril of a head-on collision, especially at night and during rush hours.

Rotaries (aka “roundabouts”), by smoothing and calming traffic, can reduce accidents, and they cut pollution from the idling of gasoline-fueled vehicles and can eliminate the need for expensive traffic lights. But the signage must be very clear – especially at night.

Better study the bridge project carefully before entering it — if you can get to it through the mess/anarchy caused by the Washington Bridge’s partial closing.

And now there’s the inevitable flap over a proposed rotary in Portsmouth, R.I. Drivers, like most people, fear change.

National Register of Historic Places plaque on the first traffic circle in the United States, at the intersection of River and Pleasant streets in Yarmouth, Mass.

Meanwhile, my friend Lisette Prince, who lives in Newport, reminded me that planting ground cover instead of grass on median strips and otherwise along the roads reduces pollution caused by gasoline-powered lawn mowers, virtually eliminates erosion and can stay green without watering for much longer than grass.

Soothing Big Periwinkle ground cover

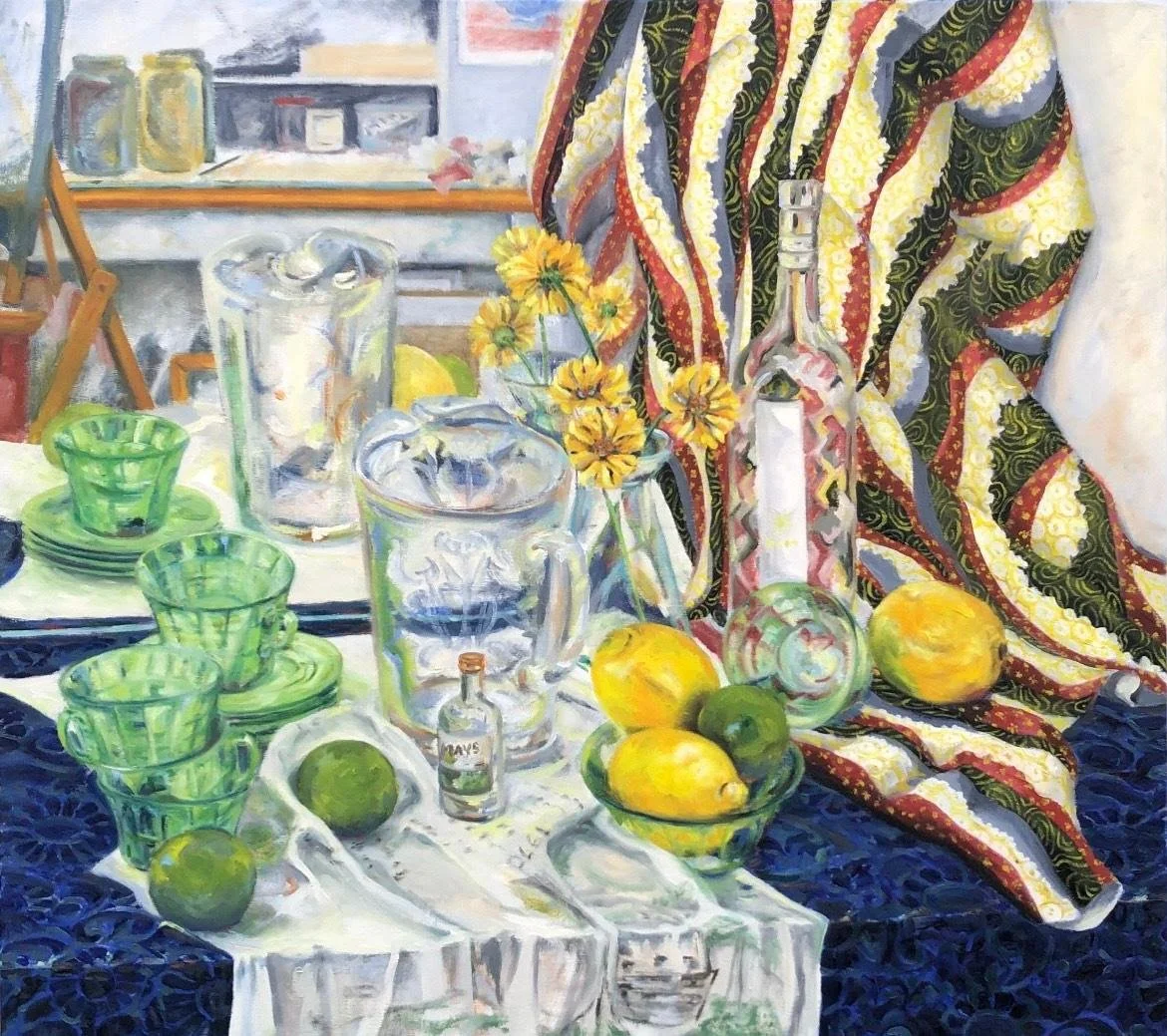

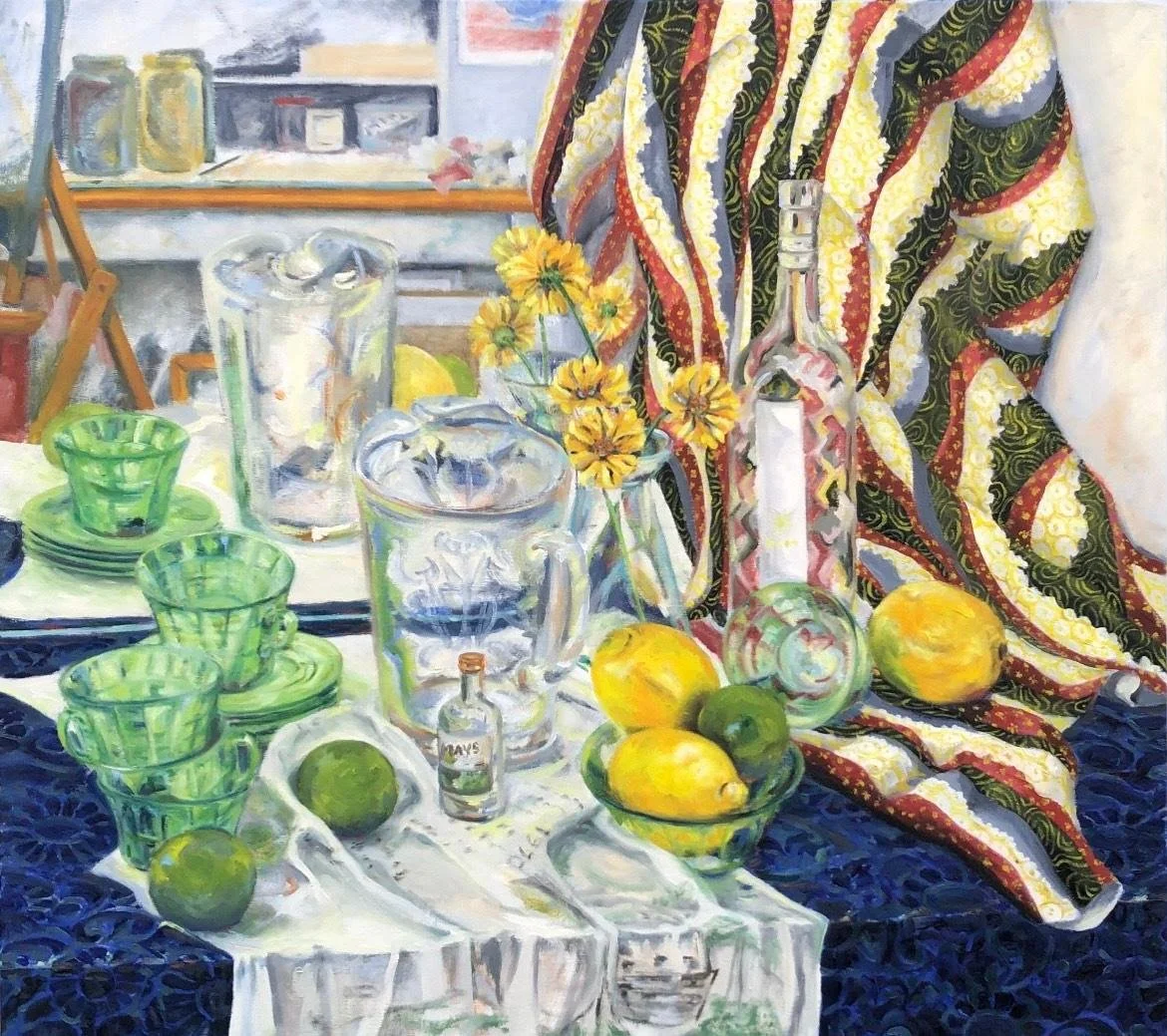

Interacting environments

From “Stems — Paintings by Melinda Lane’’, at Colo Colo Gallery, New Bedford, Mass., through Dec 31.

‘

She says on her Web site:

“Influenced by New England's architecture, and decorative arts I create paintings of interior spaces filled with objects that interest me. I focus on the interaction of decorative materials and nature. The interplay of the natural world and the decorative environment reveals itself as I study the selected objects and the surfaces they occupy. Patterns and rhythms develop as I work to create the structure and space of an interior landscape.

”The process begins with the consideration of objects, surfaces, and vantage points. Common items mix with found objects and plant material as I use color, design, and materials to create an entry point for each painting. These spaces evolve through I study of the objects in situ and develop a geometric scaffold which creates a compositional framework. How do objects interact with each other? How do they sit in space and on the surface? Do color and pattern create movement and rhythm? What shapes and ideas do I discover as I spend time looking? How many layers do I see, and do these layers create an engaging image?

”Over time, sustained observation moves me beyond literal representation, and I create a singular space from a myriad of instances, both observed in the moment and remembered experiences. Rather than present an image, I work to create a space in which the viewer can dwell, explore, and discover their own thoughts and pleasures.’’

Seasonal anonymity

Torrance York, “Untitled 5365” ( archival pigment print), by Connecticut-based photographer Torrance York, at the Danforth Art Museum, Framingham, Mass.

In Garden in the Woods, operated by the New England Wild Flower Society. It features the largest landscaped collection of native wildflowers in New England.

David Warsh: Getting personal about the Israeli-Hamas warTheY

Hamas logo

The Israeli flag

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Is it possible to criticize Israeli policy in Gaza and the West Bank without being anti-Semitic? The question seems worth asking, even if it almost certainly means being called anti-Semitic by some. Surely it is possible to deplore Hamas without being called anti-Palestinian.

I don’t know what to do with this except to be personal about it.

I grew up in a suburb of Chicago in which racism was pervasive, though mostly polite, because no people of color lived there. Unspoken replacement theology held sway – that is, the premise that Jews, followers of the Old Testament – the Hebrew Bible – eventually would be converted to the principles of the New Testament, the Christian Bible.

Folkways of the village in the Fifties exhibited some pretty strange ideas about gender, too. The use of atomic bombs and carpet bombing against civilian populations during World War II raised few objections. And as for the indigenous populations we had displaced? The hockey team was named for them.

A large part of my education since has involved escaping those prejudices, by degrees, via participation in “movements” of various sorts: college, civil rights, anti-war, pro-women, and now, opposition to Israel’s “Second War of Independence;” that is, its special military operation in Gaza.

Revolted as I was by the Hamas raid, my first reaction to the news of the massacre of some 1,200 innocents was to ask myself what Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu should have done? I had grown up to become a member of a Congregational church; I could use my confirmation instead of a birth certificate to obtain a passport, or so I was told. For a time, I had been a Zionist: I knew a good deal about the Holocaust; I had thrilled to the film Exodus in high school.

Netanyahu should have turned the other cheek, I thought, called out Hamas to worldwide disgust and scorn, and resigned. It took only a day to realize that recommending the Sermon on the Mount to the Israeli Defense Force was no solution. That set in motion this skein of thought.

I had never seen, until I came across the other day, , in an article in The Atlantic, President Dwight Eisenhower’s advice in a letter to one of his brothers, in 1954, in the early stages of the Cold War:

You speak of the “Judaic-Christian heritage.” I would suggest that you use a term on the order of “religious heritage” – this is for the reason that we should find some way of including the vast numbers of people who hold to the Islamic and Buddhist religions when we compare the religious world against the Communist world. I think you could still point out the debt we all owe to the ancients of Judea and Greece for the introduction of new ideas.

Advice as sage today as it was then. Even much-loathed former Commies might be included in the heritage of humanity today. I’ll leave it to historians, Biblical scholars, ethnologists, anthropologists, and sociologists to pick apart the differences. But theologian Paul Tillich’s phrase “Judaic-Christian heritage,” which offered such comfort during the years after World War II, is no longer part of my vocabulary.

Having said this much, I must come to the point. I am aghast at the Israeli government’s invasion and occupation of Gaza; appalled by its plan to occupy the territory after the slaughter stops; embarrassed by the United States’ veto of the 13-1 United Nations Security Council resolution calling for an immediate cease-fire.

I object to the congressional and donor bullying of university presidents. The American newspapers I follow seem to have been somewhat intimidated as well. (Here is a long view of the situation in The Guardian that makes sense to me.) The stain on the reputations of the leaders and policymakers involved, including those in the United States and Iran, can never be erased.

I have had this privilege of writing this column, called Economic Principals, for 40 years. I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t say this much about current events in the Middle East. It is, however, as much as I have to say. I’m against the war in Ukraine, too, but after twenty years of following its genesis, it is a problem I know something about.

The relevance to these matters of economics should be clear, at least intuitively. I pledge to work harder to spell it out.

xxx

Swedish Television does an excellent job on its short profiles of each year’s well Nobel laureates. The link offered here last week to their visit with Harvard economist Claudia Goldin didn’t work. Here is one that does. At fourteen minutes, it is well worth watching.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Our single-cell world

Entrance to Haddam Meadows State Park, in Haddam, Conn.

“I have been trying to think of the earth as a kind of organism, but it is no go. I cannot think of it this way. It is too big, too complex, with too many working parts lacking visible connections. The other night, driving through a hilly, wooded part of southern New England, I wondered about this. If not like an organism, what is it like, what is it most like? Then, satisfactorily for that moment, it came to me: it is most like a single cell.’’

–— Lewis Thomas (1913-1993), American physician, researcher, writer and health-care executive.

Not for rent

“Burano Venezia’’ (glicee pigment print), by Rob Skinnon, at Mix Design, Guilford, Conn.

Mr. Skinnon’s photographs display his journeys through villages of Italy, hidden backroads of New England, seascapes at Martha’s Vineyard, and beyond.

Henry Whitfield House, built in 1639, is the oldest house in Connecticut and the oldest stone house in New England. It’s very English looking.

Circa 1900 colorized postcard