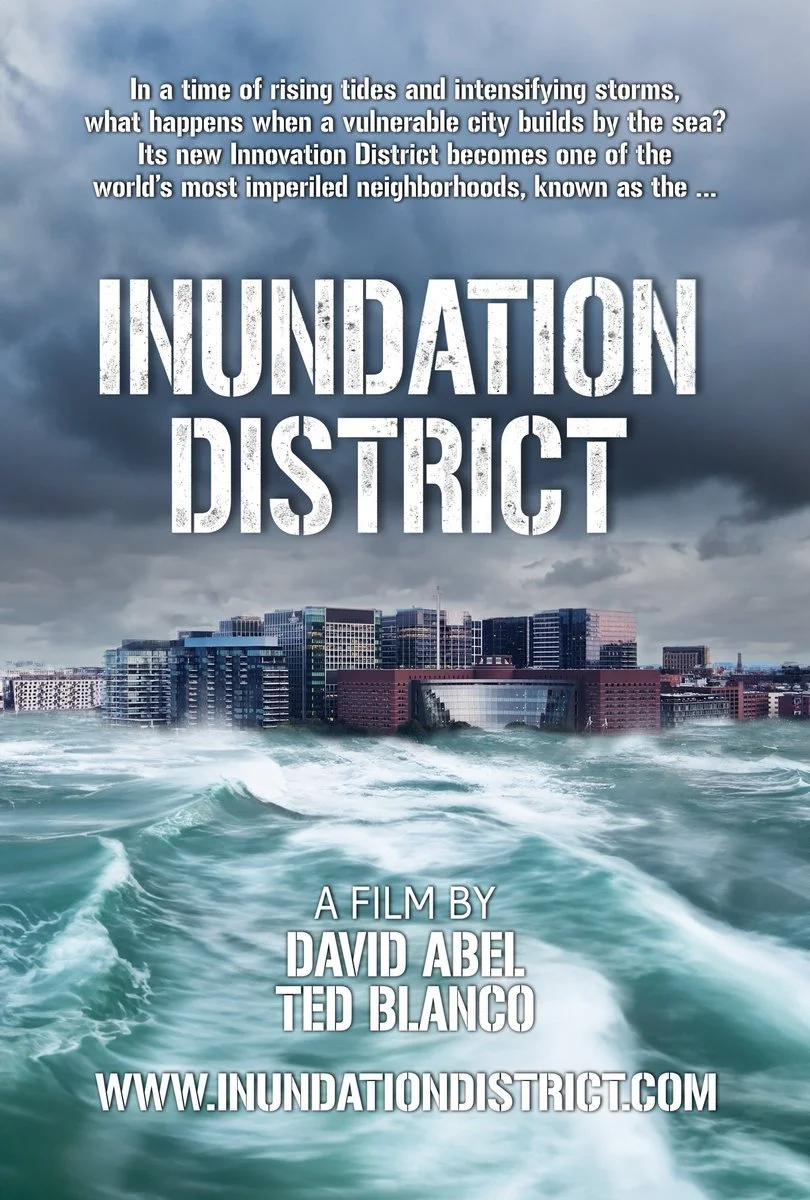

The perils facing Boston’s ‘Inundation District’

In the Seaport District, Boston Convention and Exhibition Center entry canopy at night.

— Photo by Generaltso (talk) (Uploads)

Text excerpted from The Boston Guardian

“As construction continues in such low-lying areas like the Seaport and East Boston, planners and private-sector insurance experts are warning developers and insurers to go beyond currently required building standards and consider what climate change will mean for potential flood hazards in future years.

"‘It's critical,’ said Martin Pillsbury, director of environmental planning for the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC). ‘I know there are costs involved and builders and developers always want to avoid costs, but if you ignore hazards, you're just potentially opening yourself up to loss down the road.’

"‘It drives me crazy when new developments say they're two feet above base flood elevation, but they're 10 feet below storm surge. Surge is a major risk in Boston,’ said Joe Rossi, president and CEO of Joe Flood Insurance and the founder of the Massachusetts Coastal Coalition ‘The Seaport probably should've been designed in a totally different way, that is only going to become more evident as we go down the road with more storms and environmental changes.”’

To read the full article, please hit this link.

Inundation District is a documentary film featuring interviews with residents and experts about the threats to Boston's shoreline and what the city can do now to contain the damage.

Improvised abstrations

Terry Ekasala, “Backyard,” by Terry Ekasala, in the show “Terry Ekasala: Layers of Time,’’ at Burlington (Vt.) City Arts through Jan. 27. She lives near Burke Mountain, in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom.

— Photo courtesy of Burlington City Arts

The gallery explains:

“Kasala's work is layered, dynamic and heavily improvised — experiences, personal journeys for artist and viewer alike.’’

Burke Mountain from Lyndonville, Vt.

— Photo From the nek

‘Transcendent shapes’

“Remains” (1970) ( sand and gel medium), by Merrimac, Mass.-based artist Rhoda Rosenberg, in her show “Shapes of Time: 1968-2022,’’ at Concord Art, Concord, Mass., through Dec. 17.

The gallery says:

“Rosenberg’s work focuses on deeply rooted ties with family members and the power of an object’s shape to convey feeling. Concerned with emotion and meaning behind her subject matter more than representational rendering, she has concentrated on transcendent shapes throughout her career, seeing beyond the form of an object and getting to the feeling it evokes instead.’’

Merrimac Town Hall near Merrimac Square

— Photo by Doug Kerr

Llewellyn King: America’s fossil-fuel dilemma

An LNG carrier, at right, passes just offshore of downtown Boston, under Coast Guard and police escort.

- Photo by Chris Wood

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

If when you see a sleek new Tesla in a parking lot or hear an announcement of a utility committing to solar, or that work is proceeding with converting steel-making from coal to electricity, you might think that oil and natural gas are on the ropes, that coal has left the utility scene and the new, green world is at hand.

Yes, yes, yes, Herculean efforts are underway in advanced countries to curb the use of fossil fuels, but those fuels are still dominant and will remain so for a long time. World oil consumption is now at 97 million barrels a day. It is set to rise before it falls back.

In the United States last year, according to the Energy Information Administration, natural gas accounted for 39.9 percent of electricity production; coal, 19.7 percent; nuclear, 18.2 percent; and renewables, the rest, although these are coming on fast.

A study released this October by the International Energy Agency in Paris predicts that world oil production will peak in 2030. Maybe. But one by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, also released recently, says this won’t occur until 2045 or later.

One way or another, oil remains the big enchilada of fossil fuels. Gradually it may yield to natural gas, which has become a vital part of the U.S. and global electricity scene. Eventually, it will become essential as a maritime fuel.

Oil has been phased out of U.S. electricity generation, except for emergencies. But natural gas has become the bridge, if you will, to the renewables, mainly wind and solar.

Though under threat, coal is still a vital part of U.S. electricity generation. In China and India, its share is 50 percent and rising.

Although oil may peak in 2030 0r 15 years later, it is going to be the critical transportation fuel for decades. Even if electric cars take over, and light trucks and some buses do likewise, it will be a long time before ships, trains, inter-city trucks and airplanes give it up.

New cruise ships will be powered with natural gas and some of the larger, older ones are slated to make the conversion. But for the rest of the global maritime fleet, this isn’t going to happen.

There are about 55,000 merchant ships traversing the world’s oceans. Hardly any of these will convert to compressed natural gas, which is much less polluting than the oil now burned at sea, mostly residual or diesel.

The reason they won’t convert is prohibitive cost; bunkering is a problem, too. Major new infrastructure is needed to support compressed natural gas as a maritime fuel.

Aircraft have an acute problem of their own. It arises from the way jets spew pollution at altitude, making them a potent source of greenhouse gas emissions.

While it isn’t certain how many aircraft there are in the world, estimates put large aircraft at around 23,000, and if absolutely everything that is flyable with an engine is added, it may be close to double that number.

The airlines, airframe makers and engine manufacturers are desperately seeking solutions, but so far nothing viable has emerged. Batteries are heavy and draw down quickly; hydrogen doesn’t have the energy density and is highly flammable.

No new technology is on the horizon but more people are flying, and that number appears to be exponential. Up, up and away is now an expectation for even people of modest income.

The surviving usefulness of fossil fuels globally presents U.S. policy-makers with a dilemma: It is the world’s largest oil and natural gas producer. It has a surplus of natural gas for export as liquified natural gas (LNG). The United States produces 12 million-plus barrels of oil a day, but well short of the 19 million barrels a day the nation consumes. Ergo, there is a security advantage in increasing domestic oil production, which alarms the Biden administration.

LNG exports are important not only because of their profitability, but also their stabilizing effect on world markets, as demonstrated by the Ukraine crisis.

It behooves the United States to up the production and export of natural gas while continuing downward pressure on domestic oil consumption. A simple enough proposition, except that environmentalists and the administration would like to reduce natural gas consumption and production.

New England, for example, tried to starve out gas by not installing delivery pipelines. Now LNG that should be flowing overseas to stabilize and reduce coal consumption is going to the Northeast, a costly and futile attempt at curbing greenhouse gases.

Damn those fossils! You can’t live with them, and you can’t live without them.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Tech imitating art

MIT Media Lab

View from Boston, circa 1917, of MIT’s then new campus in Cambridge. It had moved from Boston.

Patrick Stewart in 2019

Smart refugees at Newport aquarium

A Common Octopus, the kind that shows up in southern New England’s coastal waters. Octopuses are smart!

Maybe better to fly

“Offshore Voyage’’ (oil), by New Hampshire artist Liz Auffant, at Kennedy Gallery, Portsmouth, N.H.

Scanning the ‘undertow’

“Each, Every, All, None’’ (mixed media), by Brockton, Mass.-based artist Virginia Mahoney in her show with Natalie Miebach, “Undercurrents,’’ at Fountain Street Gallery, Boston, through Oct. 29.

The gallery says:

“Virginia Mahoney scans the undertow of human interactions, examining the disparity between surface appearances and underlying consequences. With complex, intricate forms and materials, her figures probe autobiographical stories and question accepted narratives. As she uncovers possibilities in the scraps, shards, and leftovers of a longstanding studio practice, her voice emerges in the rhythm of stiches, provocations of language, and discovery of new forms.’’

Headlines posted in street-corner window of newspaper office (Brockton Enterprise), 60 Main Street, Brockton, in December 1940. Upstairs were the first main offices of the W.B. Mason company.

Aneri Pattani: Using anti-opioid money for police cars

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

“You can’t just cut the police out of it. Nor would you want to.”

— Brandon del Pozo, Brown University

Some state and local governments have started tapping in to opioid settlement funds for law enforcement expenses. Many argue it should go toward treating addiction instead.

In these cases and many others, state and local governments are turning to a new means to pay those bills: opioid settlement cash.

This money — totaling more than $50 billion across 18 years — comes from national settlements with more than a dozen companies that made, sold, or distributed opioid painkillers, including Johnson & Johnson, AmerisourceBergen, and Walmart, which were accused of fueling the epidemic that addicted and killed millions.

Directing the funds to police has triggered difficult questions about what the money was meant for and whether such spending truly helps save lives.

Terms vary slightly across settlements, but, in most cases, state and local governments must spend at least 85% of the cash on “opioid remediation.”

Paving roads or building schools is out of the question. But if a new cruiser helps officers reach the scene of an overdose, does that count?

Answers are being fleshed out in real time.

The money shouldn’t be spent on “things that have never really made a difference,” like arresting low-level drug dealers or throwing people in jail when they need treatment, said Brandon del Pozo, who served as a police officer for 23 years and is currently an assistant professor at Brown University researching policing and public health. At the same time, “you can’t just cut the police out of it. Nor would you want to.”

Many communities are finding it difficult to thread that needle. With fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, flooding the streets and more than 100,000 Americans dying of overdoses each year, some people argue that efforts to crack down on drug trafficking warrant law enforcement spending. Others say their war on drugs failed and it’s time to emphasize treatment and social services. Then there are local officials who recognize the limits of what police and jails can do to stop addiction but see them as the only services in town.

What’s clear is that each decision — whether to fund a treatment facility or buy a squad car — is a trade-off. The settlements will deliver billions of dollars, but that windfall is dwarfed by the toll of the epidemic. So increasing funding for one approach means shortchanging another.

“We need to have a balance when it comes to spending opioid settlement funds,” said Patrick Patterson, vice chair of Michigan’s Opioid Advisory Commission, who is in recovery from opioid addiction. If a county funds a recovery coach inside the jail, but no recovery services in the community, then “where is that recovery coach going to take people upon release?” he asked.

Jail Technology Upgrades?

In Michigan, the debate over where to spend the money centers on body scanners for jails.

Email records obtained by KFF Health News show at least half a dozen sheriff departments discussed buying them with opioid settlement funds.

Kalamazoo County finalized its purchase in July: an Intercept body scanner marketed as a “next-generation” screening tool to help jails detect contraband someone might smuggle under clothing or inside their bodies. It takes a full-body X-ray in 3.8 seconds, the company Web site says. The price tag is close to $200,000.

Jail administrator and police Capt. Logan Bishop said they bought it because in 2016 a 26-year-old man died inside the jail after drug-filled balloons he’d hidden inside his body ruptured. And last year, staffers saved a man who was overdosing on opioids he’d smuggled in. In both cases, officers hadn’t found the drugs, but the scanner might have identified them, Bishop said.

“The ultimate goal is to save lives,” he added.

St. Clair County also approved the purchase of a scanner with settlement dollars. Jail administrator Tracy DeCaussin said six people overdosed inside the jail within the past year. Though they survived, the scanner would enhance “the safety and security of our facility.”

But at least three other counties came to a different decision.

“Our county attorney read over parameters of the settlement’s allowable expenses, and his opinion was that it would not qualify,” said Sheriff Kyle Rosa of Benzie County. “So we had to hit the brakes” on the scanner.

Macomb and Manistee counties used alternative funds to buy the devices.

Scanners are a reasonable purchase from a county’s general funds, said Matthew Costello, who worked at a Detroit jail for 29 years and now helps jails develop addiction treatment programs as part of Wayne State University’s Center for Behavioral Health and Justice.

After all, technology upgrades are “part and parcel of running a jail,” he said. But they shouldn’t be bought with opioid dollars because body scanners do “absolutely nothing to address substance use issues in jail other than potentially finding substances,” he said.

Many experts across the criminal justice and addiction treatment fields agree that settlement funds would be better spent increasing access to medications for opioid use disorder, which have been shown to save lives and keep people engaged in treatment longer, but are frequently absent from jail care.

Who Is on the Front Lines?

In August, more than 200 researchers and clinicians delivered a call to action to government officials in charge of opioid settlement funds.

“More policing is not the answer to the overdose crisis,” they wrote.

In fact, years of research suggests law enforcement and criminal justice initiatives have exacerbated the problem, they said. When officers respond to an overdose, they often arrest people. Fear of arrest can keep people from calling 911 in overdose emergencies. And even if police are accompanied by mental health professionals, people can be scared to engage with them and connect to treatment.

A study published this year linked seizures of opioids to a doubling of overdose deaths in the areas surrounding those seizures, as people turned to new dealers and unfamiliar drug supplies.

“Police activity is actually causing the very harms that police activity is supposed to be stemming,” said Jennifer Carroll, an author of that study and an addiction policy researcher who signed the call to action.

Officers are meant to enforce laws, not deliver public health interventions, she said. “The best thing that police can do is recognize that this is not their lane,” she added.

But if not police, who will fill that lane?

Rodney Stabler, chair of the board of commissioners in Bibb County, Ala., said there are no specialized mental health treatment options nearby. When residents need care, they must drive 50 minutes to Birmingham. If they’re suicidal or in severe withdrawal, someone from the sheriff’s office will drive them.

So Stabler and other commissioners voted to spend about $91,000 of settlement funds on two Chevy pickups for the sheriff’s office.

“We’re going to have to have a dependable truck to do that,” he said.

Commissioners also approved $26,000 to outfit two new patrol vehicles with lights, sirens, and radios, and $5,500 to purchase roadside cameras that scan passing vehicles and flag wanted license plates.

Stabler said these investments support the county agencies that most directly deal with addiction-related issues: “I think we’re using it the right way. I really do.”

Shawn Bain, a retired captain of the Franklin County, Ohio, sheriff’s office, agrees.

“People need to look beyond, ‘Oh, it’s just a vest or it’s just a squad car,’ because those tools could impact and reduce drugs in their communities,” said Bain, who has more than 25 years of drug investigation experience. “That cruiser could very well stop the next guy with five kilos of cocaine,” and a vest “could save an officer’s life on the next drug raid.”

That’s not to say those tools are the solution, he added. They need to be paired with equally important education and prevention efforts, he said.

However, many advocates say the balance is off. Law enforcement has been well funded for years, while prevention and treatment efforts lag. As a result, law enforcement has become the de facto front line, even if they’re not well suited to it.

“If that’s the front lines, we’ve got to move the line,” said Elyse Stevens, a primary care doctor at University Medical Center New Orleans, who specializes in addiction. “By the time you’re putting someone in jail, you’ve missed 10,000 opportunities to help them.”

Stevens treats about 20 patients with substance use disorder daily and has appointments booked out two months. She skips lunch and takes patient calls after hours to meet the demand.

“The answer is treatment,” she said. “If we could just focus on treating the patient, I promise you all of this would disappear.”

Sheriffs to Be Paid Millions

In Louisiana, where Stevens works, 80% of settlement dollars are flowing to parish governments and 20% to sheriffs’ departments.

Over the lifetime of the settlements, sheriffs’ offices in the state will receive more than $65 million — the largest direct allocation to law enforcement nationwide.

And they do not have to account for how they spend it.

While parish governments must submit detailed annual expense reports to a statewide opioid task force, the state’s settlement agreement exempts sheriffs.

Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry, who authored that agreement and has since been elected governor, did not respond to questions about the discrepancy.

Chester Cedars, president of St. Martin parish and a member of the Louisiana Opioid Abatement Task Force, said he’s confident sheriffs will spend the money appropriately.

“I don’t see a whole lot of sheriffs trying to buy bullets and bulletproof vests,” he said. Most are “eager to find programs that will keep people with substance abuse problems out of their jails.”

Sheriffs are still subject to standard state audits and public records requests, he said.

But there’s room for skepticism.

“Why would you just give them a check” with nothing “to make sure it’s being used properly?” said Tonja Myles, a community activist and former military police officer who is in recovery from addiction. “Those are the kinds of things that mess with people’s trust.”

Still, Myles knows she has to work with law enforcement to address the crisis. She’s starting a pilot program with Baton Rouge police, in which trained people with personal addiction experience will accompany officers on overdose calls to connect people to treatment. East Baton Rouge Parish is funding the pilot with $200,000 of settlement funds.

“We have to learn how to coexist together in this space,” Myles said. “But everybody has to know their role.”

Aneri Pattani is a KFF Health News reporter.

'Shining on the sad abodes of death'

William Cullen Bryant homestead in Cummington, Mass.

To him who in the love of Nature holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language; for his gayer hours

She has a voice of gladness, and a smile

And eloquence of beauty, and she glides

Into his darker musings, with a mild

And healing sympathy, that steals away

Their sharpness, ere he is aware. When thoughts

Of the last bitter hour come like a blight

Over thy spirit, and sad images

Of the stern agony, and shroud, and pall,

And breathless darkness, and the narrow house,

Make thee to shudder, and grow sick at heart;—

Go forth, under the open sky, and list

To Nature’s teachings, while from all around—

Earth and her waters, and the depths of air—

Comes a still voice—

Yet a few days, and thee

The all-beholding sun shall see no more

In all his course; nor yet in the cold ground,

Where thy pale form was laid, with many tears,

Nor in the embrace of ocean, shall exist

Thy image. Earth, that nourished thee, shall claim

Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again,

And, lost each human trace, surrendering up

Thine individual being, shalt thou go

To mix for ever with the elements,

To be a brother to the insensible rock

And to the sluggish clod, which the rude swain

Turns with his share, and treads upon. The oak

Shall send his roots abroad, and pierce thy mould.

Yet not to thine eternal resting-place

Shalt thou retire alone, nor couldst thou wish

Couch more magnificent. Thou shalt lie down

With patriarchs of the infant world—with kings,

The powerful of the earth—the wise, the good,

Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past,

All in one mighty sepulchre. The hills

Rock-ribbed and ancient as the sun,—the vales

Stretching in pensive quietness between;

The venerable woods—rivers that move

In majesty, and the complaining brooks

That make the meadows green; and, poured round all,

Old Ocean’s gray and melancholy waste,—

Are but the solemn decorations all

Of the great tomb of man. The golden sun,

The planets, all the infinite host of heaven,

Are shining on the sad abodes of death,

Through the still lapse of ages. All that tread

The globe are but a handful to the tribes

That slumber in its bosom.—Take the wings

Of morning, pierce the Barcan wilderness,

Or lose thyself in the continuous woods

Where rolls the Oregon, and hears no sound,

Save his own dashings—yet the dead are there:

And millions in those solitudes, since first

The flight of years began, have laid them down

In their last sleep—the dead reign there alone.

So shalt thou rest, and what if thou withdraw

In silence from the living, and no friend

Take note of thy departure? All that breathe

Will share thy destiny. The gay will laugh

When thou art gone, the solemn brood of care

Plod on, and each one as before will chase

His favorite phantom; yet all these shall leave

Their mirth and their employments, and shall come

And make their bed with thee. As the long train

Of ages glide away, the sons of men,

The youth in life’s green spring, and he who goes

In the full strength of years, matron and maid,

The speechless babe, and the gray-headed man—

Shall one by one be gathered to thy side,

By those, who in their turn shall follow them.

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave,

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

“Thanatopsis,’ (1817), by William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878), American poet and long-time editor of The New York post.. He was born in Cummington, Mass. His father, Peter Bryant, was a prominent doctor with a substantial personal library who provided him with much of his early education.

But don’t go in

“Tower” (acrylic on canvas), by Peggy Wilson, in her show “Peggy Watson: Vermont Outdoors,’’ at the Northeast Kingdom Artisans Guild, St. Johnsbury, through Nov. 11.

Edited from a Wikipedia summary : In the mid-19th Century, St. Johnsbury became a minor manufacturing center, with the main products scales—the platform scale was invented there by Thaddeus Fairbanks, in 1830—and maple syrup and related products. With the arrival of the railroad line from Boston to Montreal in the 1850s, St. Johnsbury grew quickly and was named the shire town (county seat) in 1856, replacing Danville.

‘Biological narratives’

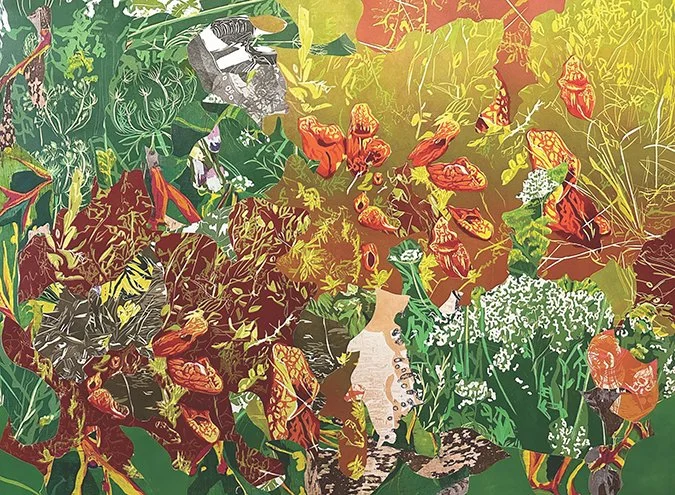

Untitled work (woodcut and lithograph collage) by Maine-based artist Amanda Lilleston in her show “Deep Field,’’ at The Zillman Art Museum, Bangor, Maine, through Dec. 30.

The museum says:

“Amanda Lilleston explores biological narratives through woodcut printing and collage in her exhibition deep field. The prints highlight the concept of transformation, depicted in burgeoning colors of flora. Lilleston began this body of work about ten years ago – the idea stemming from, ‘a broader, general interconnectedness of systems: biological, physiological, and ecological.’

“The themes that permeate her artwork reflect Lilleston’s educational and life experience – as well as motherhood. The artist explains that she has become ‘acutely aware of my body being part of a larger environment.’ Lilleston thoughtfully examines these natural subjects to allow for adaptation and change within the imagery.”

Turn of the 20th Century postcard. Bangor was for years one of the world’s lumber capitals because of its proximity to the Great North Woods and that Bangor was the last deep water port on the Penobscot River. It also had good freight and passenger rail service.

1918 logo

Chris Powell: Could Conn. suburbs get city life without its nastiness?

A shell in which to put housing?

—Photo by Justin Cozart

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Maybe a couple of the state's problems can solve each other.

Many suburban shopping malls are fading and failing as many people increasingly shop from home via the Internet and have their purchases delivered. With its COVID hysteria, government keeps scaring them against going out, and with the economy’s problems, many people can't afford to buy as much.

Meanwhile, Connecticut has a desperate shortage of housing, and soaring housing prices are a major cause of the worsening poverty in the state.

So property developers here and around the country are interested in converting fading and failed malls to housing or attaching multi-family housing to them.

Since mall property is already in commercial use and fully equipped with utilities, zoning obstacles and neighborhood objections should be much reduced, and new residents on site might substantially increase the customer base for retailers and professional services remaining in a mall. If enough housing at malls was built, housing costs would diminish for everyone.

A project successfully combining a shopping mall with a lot of new housing might create a walkable environment with much less need for cars -- making something resembling city life available in the suburbs without the poverty-induced nastiness that has overtaken most cities.

Sustaining rather than eradicating poverty would remain big business for government, but any substantial increase in housing might do more to reduce poverty than any other government social program.

xxx

New Haven sometimes seems to be striving to embody the metaphor about rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

The city's Peace Commission may think that it has achieved the big objective cited on its Internet site -- averting nuclear war -- but it seems to have been surprised by Gaza's recent attack on Israel. And though crime continues to plague New Haven while more than three-quarters of the city's schoolchildren are not performing at grade level, many being chronically absent, the other day a committee of the city council found time for a different issue: whether the city should become the first municipality in Connecticut to prohibit the sale of menthol cigarettes.

The Federal Food and Drug Administration is also moving to ban menthol cigarettes. The rationale offered is that menthol flavoring in cigarettes appeals especially to children and members of racial minorities. The unstated rationale is that children and racial minorities can't be persuaded to avoid smoking.

A municipal ban would be only pious posturing. It would not stop city residents from crossing the city line to buy menthol cigarettes in adjacent towns. Indeed, a ban well might create another contraband market in the city. Even federal law and state law haven't prevented deadly drugs like heroin and fentanyl from ravaging New Haven and other cities.

Besides, a municipal ban on menthol cigarettes would be laughably hypocritical, insofar as New Haven has approved five marijuana dispensaries in the city, though marijuana presents health risks as serious as those of menthol cigarettes. But somehow marijuana has become politically correct.

Why are New Haven's elected officials bothering with this silliness? Probably for the same reason that state legislators also spend so much time on the trivial. It distracts from their irrelevance to the big dangers of everyday life and Connecticut's longstanding problems that are never solved as the state continues to decline.

xxx

Electricity rates aren't the only place where state government imposes hidden taxes.

A recent report in the Connecticut Mirror reminded about another tax-hiding mechanism, the state's tax on bulk sales of gasoline, which lately has been about 22 cents per gallon. Gas stations pay the tax to wholesalers and recover it from their customers at the pump, where the retail sales tax is added, another 25 cents per gallon.

Drivers have some idea of the retail sales tax, especially since state government reduced it temporarily after the gas price spike resulting from Russia's invasion of Ukraine and the international sanctions on Russian oil. But few people know about the wholesale tax.

The wholesale tax on gas is another way state government encourages people to blame industry for high prices when government itself is largely responsible.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Reality of spaces’

“A Conversation with Sparrows” (oil paint, india ink and charcoal on unstretched canvas), by Imo Nse Imeh, in the group show “The Miracle Machine: A Black Artists Think Tank ,’’ through Dec. 8, at the Augusta Savage Gallery, at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Photo courtesy of UMass Amherst Fine Arts Center

The gallery says the artists in the show:

“C}onsider themes of identity, belonging, brotherhood, and Blackness, while acknowledging the reality of spaces that allow us, or that deny us, and that ultimately change us."

Make sure the ax is well-cooked

—Photo by Rhododendrites

“Everybody remembers the recipe for cooking a coot: put an ax in the pan with the coot, and when you can stick a fork in the ax, the coot is done.’’

— John Gould (1908-2003), Maine-based (mostly humorous) writer, in “They Come High,’’ in New England: The Four Seasons (1980)

Coot are coastal birds that hunters in New England shoot at in the fall, despite their tough, oily flesh.

MassArt’s Common Good Awards

Poster for MassArt’s 2024 Auction Call for Art

Edited from a New England Council report

BOSTON

“The Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt), in Boston, has announced the launch of the inaugural Common Good Awards, in celebration of its 150th anniversary as a higher-education institution.

“The awards will honor five to six exceptional individuals whose work has furthered the arts within the public sector, especially within the New England region. These efforts could come in all shapes and sizes, from an architect creating beautiful public spaces, to a civil servant whose advocacy leads to the creation of important arts programs and experiences.

“In addition to the handful of open nomination awards, there are also two specialized honors that MassArt will hand out. The first will go to a MassArt Alumnus, whose education propelled them to effectively deliver arts to the public. Additionally, the Frances Euphemia Thompson Award for Excellence in Teaching will go to a current or retired Massachusetts public school art teacher from grades K-12, whose commitment in the classroom has instilled the value of the arts into the community. The final awards ceremony is scheduled for Dec. 16.

“As the only independent, publicly funded arts and design college in the US, MassArt understands its importance as an intersection space for art and public function. ‘Arts, culture, and design are everywhere, embedded in all facets of our lives. As a public institution, we exist at the nexus of service, civic life, arts, and culture,’ said President Mary Grant.’’

Read more from MassArt.

Brief flush through the window

Autumn in New Hampshire woods

“We’re in New England, after all.

Though rippling foliage fills

the pane, the flush that tints the wall

will last a week or two, no more.’’

— From ”North-Looking Room,’’ by Brad Leithauser (born 1953), American novelist, poet and teacher.

To read the whole poem, please hit this link.

Solidarity with Israel in Boston

— Photo by Rick Friedman

The D. L. Saunders Company and The Boston Guardian unveiled a total of 10,000 American and Israeli flags — 5,000 for each country — in Statler Park, in downtown Boston, on Oct. 18. They will be on display through Oct. 22

The flags were planted by Andrew Lafuente in about six hours.

In attendance were Israeli Consul General Meron Reuben, City Council President Ed Flynn, State Representatives Aaron Michlewitz, Jay Livingstone and John Moran, Back Bay Association President Meg Mainer Cohen, Boston Guardian Publisher David Jacobs and Associate Editor Gen Tracy, and Red Sox Senior Vice President David Friedman.

Polls suggest that about 75 percent of Americans take Israel’s side in the war started by Hamas on Oct. 7.

Llewellyn King: When people come to love to hate

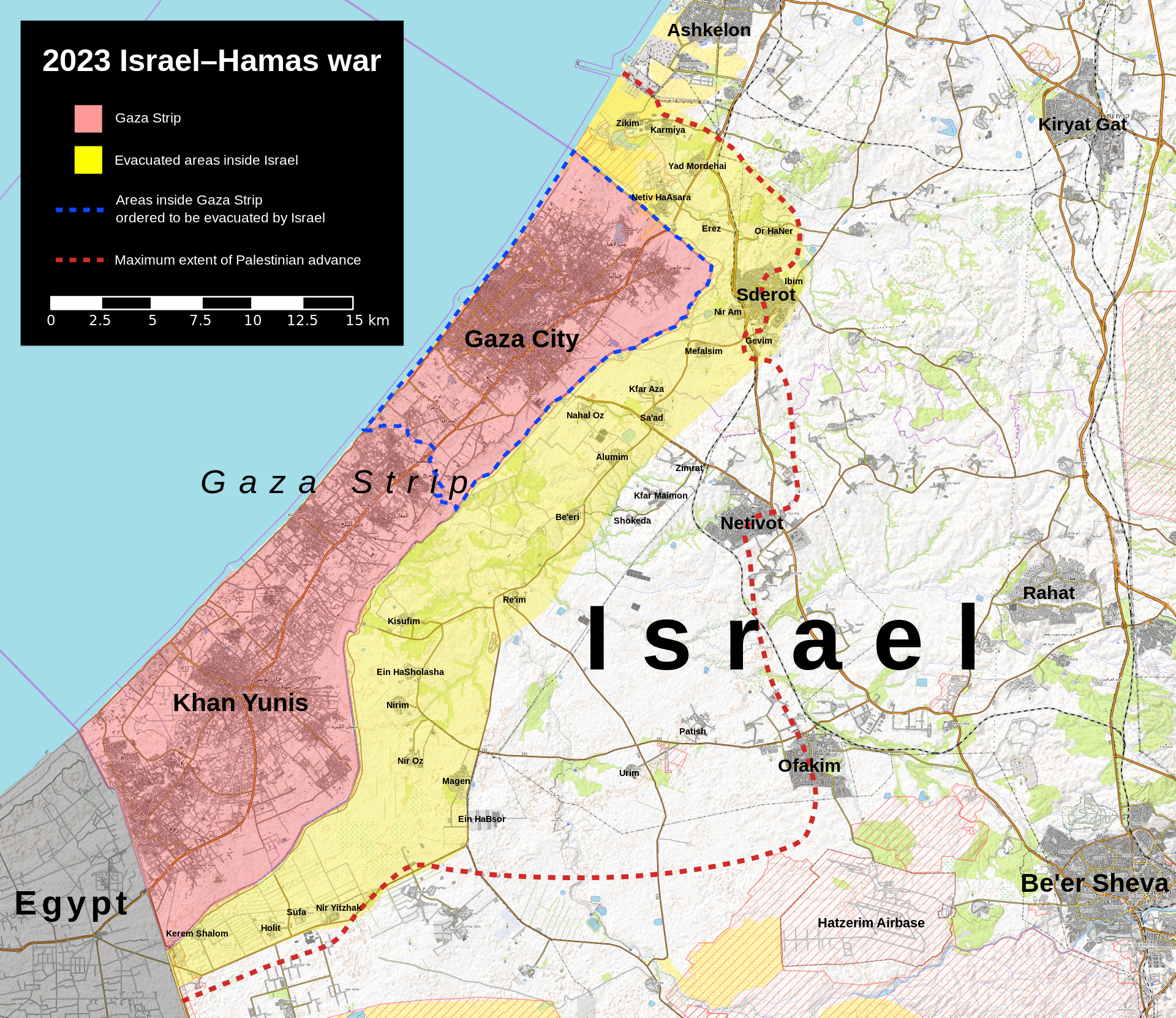

Hamas−Israel conflict at start of war, on Oct. 7-8.

— Photo by Ecrusized

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Many years ago, I was mugged in Washington.

I was looking for an informal club of the kind that sprang up after hours around big newspapers. These “clubs” were usually just an apartment with beer, liquor and card games for those of us who finished work after midnight.

The club I was looking for was on 14th Street, which was considered a bad part of town. I never got there: I was jumped and punched by a group of teenagers, who threw me to the ground and took my wallet.

My colleagues at The Washington Post brushed it off as being my fault, a self-inflicted wound — no excuses for my nocturnal wanderings.

I was bruised and felt ashamed of my stupidity. But Barry Sussman, an editor, said, “Llewellyn, you didn’t mug yourself.”

It is a sentiment that comforted my shaken self then and has stuck with me. Incidentally, Sussman was the unsung hero of the Watergate story: He edited the reporting as it came in.

My initial reaction to the carnage in Israel was, “What happened to Israeli intelligence? Where was the vaunted Mossad? By extension, where was the CIA, known to work closely with Mossad?”

Once on the Golan Heights, an Israel Defense Forces officer stood with me and boasted about how, with American-supplied gear, the military could listen to telephone calls in Jordan or watch a Syrian soldier on the plain below leave his tent to pee in the night.

So where was the surveillance, and what of human intelligence?

Thousands from Gaza went into Israel every day to work. Surely someone would have seen something; someone would have blown the whistle on Hamas’s intention to wreck mayhem on innocent Israelis — 1,400 were butchered.

Anthony Wells, a retired intelligence officer and author, who uniquely served in both the British and American intelligence services, told me in an interview on our television program, White House Chronicle, that the administration of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was partly to blame. He said the prime minister had leaned toward Hamas, ignoring the Palestinian Authority, and sometimes ignoring Mossad. This, plus political unrest in Israel over Netanyahu’s plan to curtail the power of the Supreme Court, added to the intelligence failure.

But Israel didn’t mug itself.

The planners of the industrial-scale murder of Israelis at a music “festival for peace,” of all things, had to know that Israel would take terrible revenge; that the hurt to the people living in the Gaza Strip would exceed the hurt brought to Israel; that the vengeance would be swift and terrible.

I have noticed that where there is long-enduring hatred, as between the Greeks and the Turks, the Protestants and the Catholics in Northern Ireland, and the Shona and Ndebele in Zimbabwe, hating has its own life. People come to love to hate, to revel in it, even to find a kind of comfort in it.

Hatred also is taught, handed down through the generations.

In the Arab-Israeli conflict, the Arabs have come to treasure their suffering and to love their hating. But, as Wells told me, wars of vengeance have a price: Witness the U.S. response to 9/11 with the invasion of Afghanistan.

The suffering on both sides in the Israel-Gaza conflict is hard to process. The screaming of wounded children, the hopelessness of those who won’t be whole again, the agony of those who pray for death as they lie under rubble, hoping only for quick release.

The Israeli-Palestinian peace process is now put asunder. It went on too long without peace.

David Haworth, the late English journalist, said, “I’m tired of the process, where is the peace.?” Exactly. Now it may be decades away as Israel digs in and the Palestinians ramp up their devotion to victimhood.

The blame game for what happened is in full swing: anger at the intelligence failure; the national distractions in Israel, initiated by Netanyahu; the slow response by the Israel Defense Forces.

I must remind myself over and over again, as my heart goes out to the people of Gaza, and the generations which will pay the price, that Israel didn't mug itself: It was invaded by terrorists for the purpose of terror.

My parting thought: The mass killing of the kind in Israel and Ukraine diminishes all of us. It makes the individual, far from the slaughter, feel very insignificant — and lucky.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

We must fight back

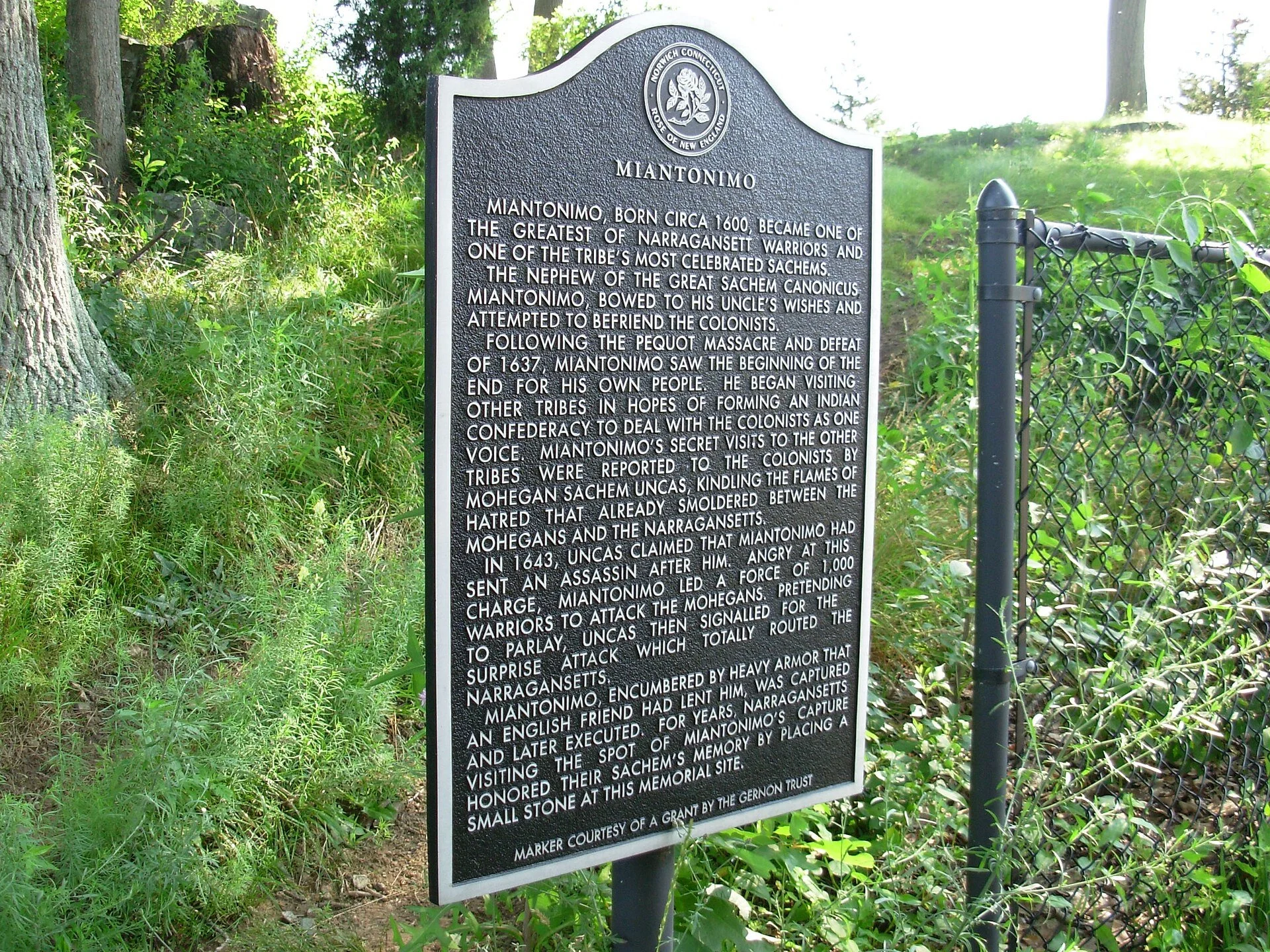

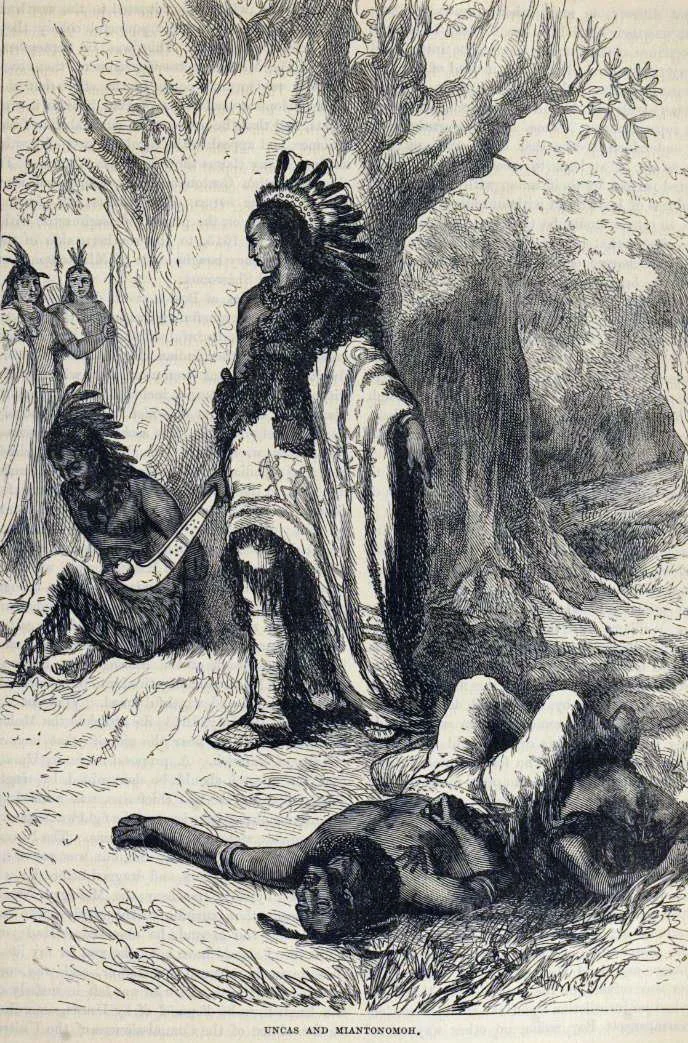

Miantonomi monument in Newport

Below is speech by the Narragansett Tribe sachem Miantonomi (1600 (circa)-1663) in 1640 in response to the relentless land grabs by English settlers. There are various spellings of the sachem’s name.

Brethren and friends, for so are we all Indians as the English are, and say brother to one another; so we must be one as they are, otherwise we shall be all gone shortly, for you know our fathers had plenty of deer and skins, our plains were full of deer, as also our woods, and of turkies, and our coves full of fish and fowl. But these English having gotten our land, they with scythes cut down the grass, and with axes fell the trees; their cows and horses eat the grass, and their hogs spoil our clam banks, and we shall all be starved; therefore it is best for you to do as we, for we are all the Sachems frome east to west, both Moquakues and Mohauks join with us, and we are all resolved to fall upon them all, at one appointed day.

An 1874 illustration of Uncas killing Miantonomi in 1643