Solidarity with Israel in Boston

— Photo by Rick Friedman

The D. L. Saunders Company and The Boston Guardian unveiled a total of 10,000 American and Israeli flags — 5,000 for each country — in Statler Park, in downtown Boston, on Oct. 18. They will be on display through Oct. 22

The flags were planted by Andrew Lafuente in about six hours.

In attendance were Israeli Consul General Meron Reuben, City Council President Ed Flynn, State Representatives Aaron Michlewitz, Jay Livingstone and John Moran, Back Bay Association President Meg Mainer Cohen, Boston Guardian Publisher David Jacobs and Associate Editor Gen Tracy, and Red Sox Senior Vice President David Friedman.

Polls suggest that about 75 percent of Americans take Israel’s side in the war started by Hamas on Oct. 7.

Llewellyn King: When people come to love to hate

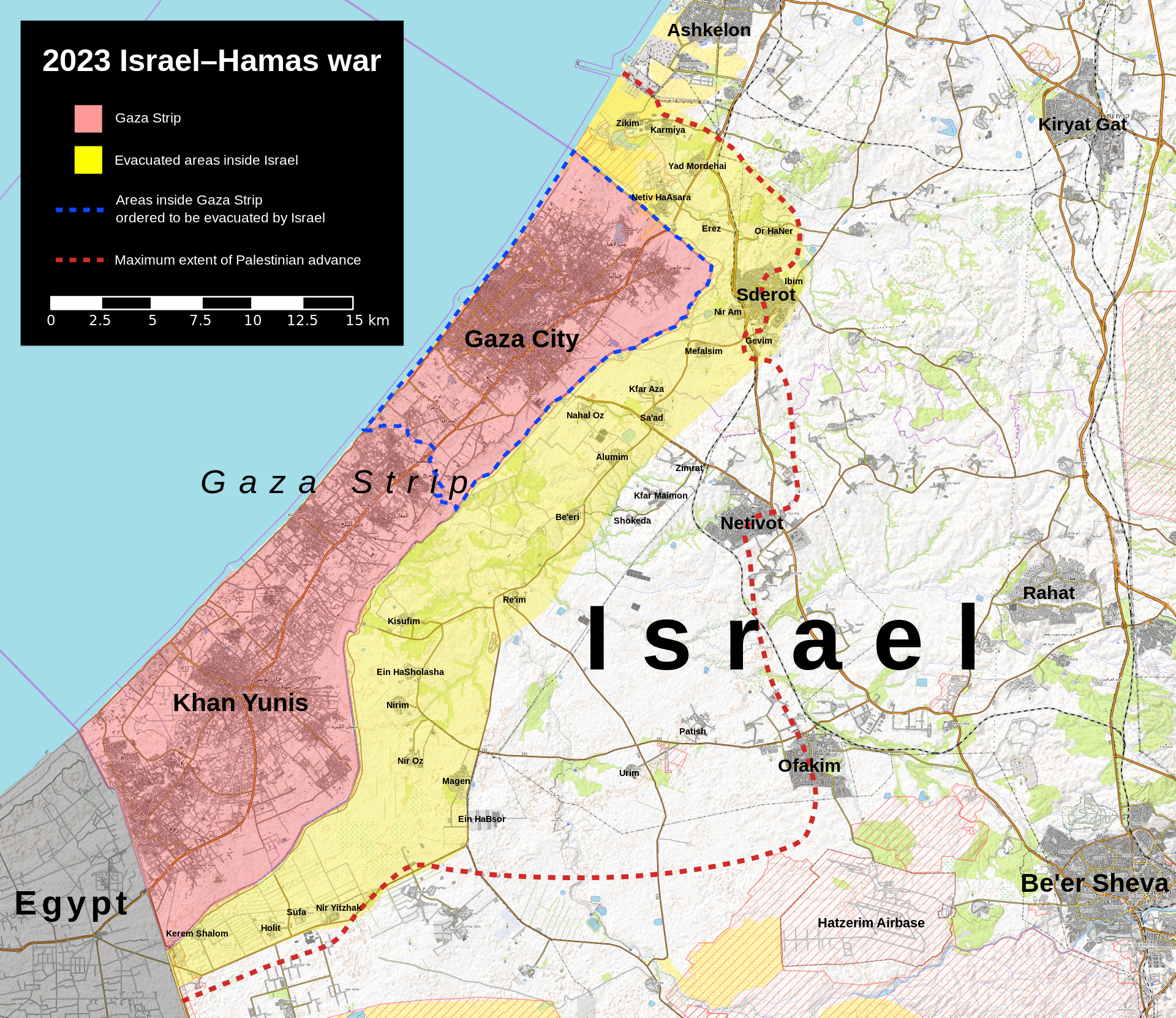

Hamas−Israel conflict at start of war, on Oct. 7-8.

— Photo by Ecrusized

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Many years ago, I was mugged in Washington.

I was looking for an informal club of the kind that sprang up after hours around big newspapers. These “clubs” were usually just an apartment with beer, liquor and card games for those of us who finished work after midnight.

The club I was looking for was on 14th Street, which was considered a bad part of town. I never got there: I was jumped and punched by a group of teenagers, who threw me to the ground and took my wallet.

My colleagues at The Washington Post brushed it off as being my fault, a self-inflicted wound — no excuses for my nocturnal wanderings.

I was bruised and felt ashamed of my stupidity. But Barry Sussman, an editor, said, “Llewellyn, you didn’t mug yourself.”

It is a sentiment that comforted my shaken self then and has stuck with me. Incidentally, Sussman was the unsung hero of the Watergate story: He edited the reporting as it came in.

My initial reaction to the carnage in Israel was, “What happened to Israeli intelligence? Where was the vaunted Mossad? By extension, where was the CIA, known to work closely with Mossad?”

Once on the Golan Heights, an Israel Defense Forces officer stood with me and boasted about how, with American-supplied gear, the military could listen to telephone calls in Jordan or watch a Syrian soldier on the plain below leave his tent to pee in the night.

So where was the surveillance, and what of human intelligence?

Thousands from Gaza went into Israel every day to work. Surely someone would have seen something; someone would have blown the whistle on Hamas’s intention to wreck mayhem on innocent Israelis — 1,400 were butchered.

Anthony Wells, a retired intelligence officer and author, who uniquely served in both the British and American intelligence services, told me in an interview on our television program, White House Chronicle, that the administration of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was partly to blame. He said the prime minister had leaned toward Hamas, ignoring the Palestinian Authority, and sometimes ignoring Mossad. This, plus political unrest in Israel over Netanyahu’s plan to curtail the power of the Supreme Court, added to the intelligence failure.

But Israel didn’t mug itself.

The planners of the industrial-scale murder of Israelis at a music “festival for peace,” of all things, had to know that Israel would take terrible revenge; that the hurt to the people living in the Gaza Strip would exceed the hurt brought to Israel; that the vengeance would be swift and terrible.

I have noticed that where there is long-enduring hatred, as between the Greeks and the Turks, the Protestants and the Catholics in Northern Ireland, and the Shona and Ndebele in Zimbabwe, hating has its own life. People come to love to hate, to revel in it, even to find a kind of comfort in it.

Hatred also is taught, handed down through the generations.

In the Arab-Israeli conflict, the Arabs have come to treasure their suffering and to love their hating. But, as Wells told me, wars of vengeance have a price: Witness the U.S. response to 9/11 with the invasion of Afghanistan.

The suffering on both sides in the Israel-Gaza conflict is hard to process. The screaming of wounded children, the hopelessness of those who won’t be whole again, the agony of those who pray for death as they lie under rubble, hoping only for quick release.

The Israeli-Palestinian peace process is now put asunder. It went on too long without peace.

David Haworth, the late English journalist, said, “I’m tired of the process, where is the peace.?” Exactly. Now it may be decades away as Israel digs in and the Palestinians ramp up their devotion to victimhood.

The blame game for what happened is in full swing: anger at the intelligence failure; the national distractions in Israel, initiated by Netanyahu; the slow response by the Israel Defense Forces.

I must remind myself over and over again, as my heart goes out to the people of Gaza, and the generations which will pay the price, that Israel didn't mug itself: It was invaded by terrorists for the purpose of terror.

My parting thought: The mass killing of the kind in Israel and Ukraine diminishes all of us. It makes the individual, far from the slaughter, feel very insignificant — and lucky.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

We must fight back

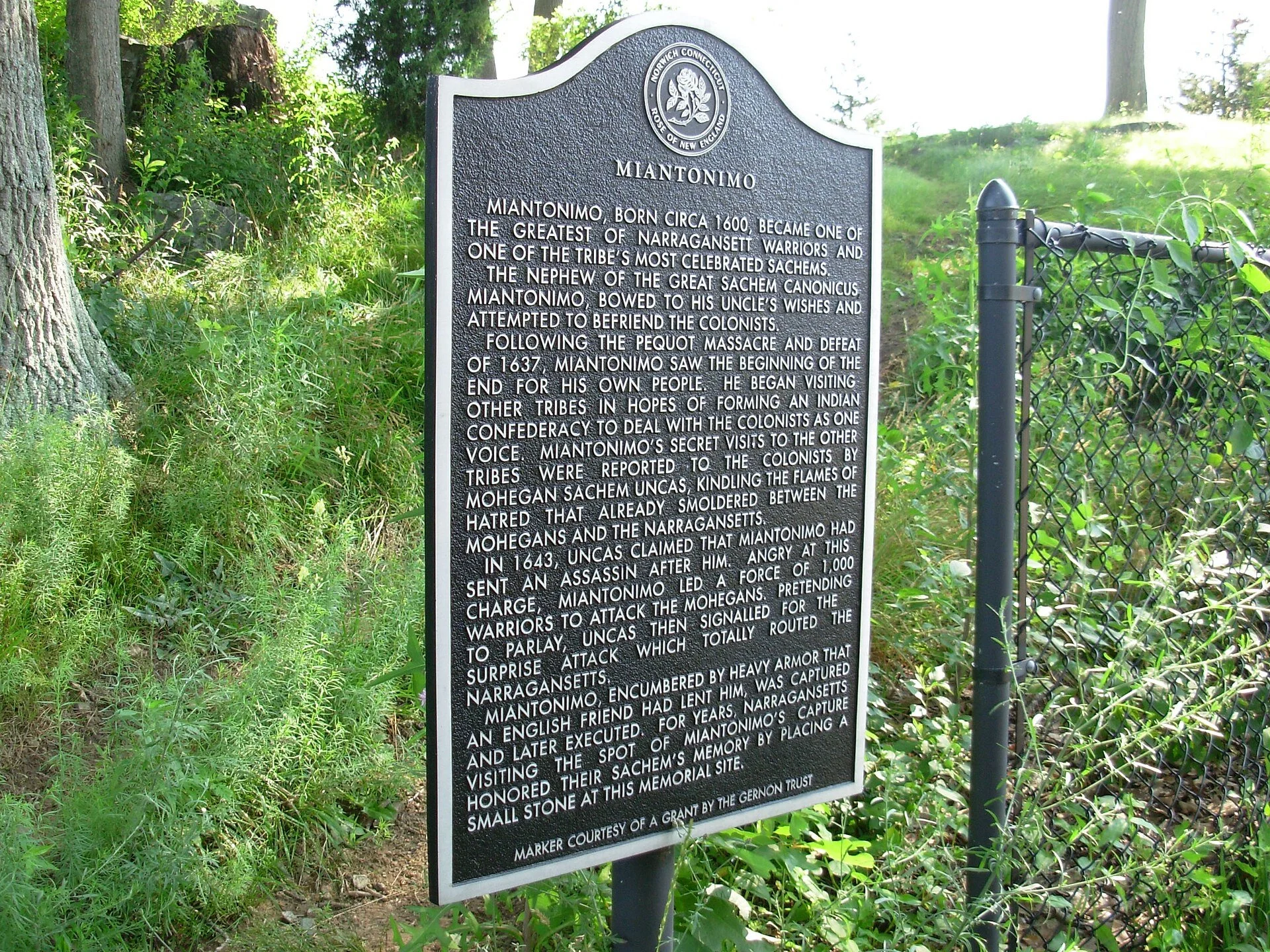

Miantonomi monument in Newport

Below is speech by the Narragansett Tribe sachem Miantonomi (1600 (circa)-1663) in 1640 in response to the relentless land grabs by English settlers. There are various spellings of the sachem’s name.

Brethren and friends, for so are we all Indians as the English are, and say brother to one another; so we must be one as they are, otherwise we shall be all gone shortly, for you know our fathers had plenty of deer and skins, our plains were full of deer, as also our woods, and of turkies, and our coves full of fish and fowl. But these English having gotten our land, they with scythes cut down the grass, and with axes fell the trees; their cows and horses eat the grass, and their hogs spoil our clam banks, and we shall all be starved; therefore it is best for you to do as we, for we are all the Sachems frome east to west, both Moquakues and Mohauks join with us, and we are all resolved to fall upon them all, at one appointed day.

An 1874 illustration of Uncas killing Miantonomi in 1643

‘A floating world’

“Territory” (oil on canvas), by Suzanne Onodera, at Argazzi Art, Lakeville, Conn.

She says:

"I use the physicality of paint, color and gesture to create multi-layered lush landscapes that are drawn from my observations and experiences in nature. Bridging the abstract and the realistic, these places are extracted solely from my imagination, illustrating a sublime floating world that is simultaneously chaotic and unsettled, exalted and sublime. Always constant in the work is a search for beauty, mystery and ambiguity."

In the Hockomock Swamp. The swamp and its associated wetlands and water bodies comprise the largest freshwater wetland system in Massachusetts. The includes about 16,950 acres in the southeastern part of the state.

Why we need Lapham’s Quarterly

See:

Laphamsquarterly.org

Celebrated critic Ron Rosenbaum, writing in Smithsonian Magazine, argues that Lapham’s Quarterly solves “the great paradox of the digital age”

“Suddenly thanks to Google Books, JSTOR, and the like, all the great thinkers of all the civilizations past and present are one or two clicks away. The great library of Alexandria, nexus of all the learning of the ancient world that burned to the ground, has risen from the ashes online. And yet—here is the paradox—the wisdom of the ages is in some ways more distant and difficult to find than ever, buried like lost treasure beneath a fathomless ocean of online ignorance and trivia that makes what is worthy and timeless more inaccessible than ever. There has been no great librarian of Alexandria, no accessible finder’s guide, until Lewis Lapham created his quarterly…with the quixotic mission of serving as a highly selective search engine for the wisdom of the past.”

“Lapham’s Quarterly is a godsend, a genuine treasure for any and all who care about history and ideas and the love of learning. It is superbly edited, beautifully designed and illustrated, and has a good tactile presence exactly in the spirit of its purpose. I don’t know when I’ve been so pleased by something that arrived in the mail unexpectedly. Bravo!”

—David McCullough

“No matter how many magazines and journals to which you may subscribe, Lapham’s Quarterly is a necessity. From its very first issue, it has become the Thinking Person’s Guide to where we’ve come from, where we are, and where we may be going. Lewis Lapham’s name on the cover is enough to tell you, you’re in for an intellectual treat.”

—Morley Safer

“Lavishly detailed, handsomely produced, and conceptually brilliant...It recontextualizes history and makes it come alive to the sound of battle.”

—James Wolcott, Vanity Fair

“Enthralling reading... A magazine that demands focus and engages intellect in order to elicit persuasive emotions.”

—Francesca Mari, The New Republic

“It is not the next big thing; it is the real thing, a must-read.”

—Ken Alexander, The Walrus (Canada)

“Expertly edited and easy to read.”

—The Age (Australia)

“Expertly presented, with a soft matte finish and subdued colors, the magazine has a look and feel that reflect the quality of the fine writing. Essential for academic libraries; highly recommended for public libraries.”

—Steve Black, Library Journal

Projecting our drinking-water needs in a warmer and wetter climate

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Discussions come up from time to time about whether to create another Rhode Island state reservoir, in the Big River Management Area, to supplement the Scituate Reservoir. To be useful they must consider scientifically and actuarily based projections of the effects of global warming as well as of population growth.

Given that New England is expected to become wetter over the next few decades, will the Ocean State really need another big reservoir? Maybe. A Big River Reservoir would apparently be mostly for the fast-developing southern part of Rhode Island, and development pressures around here will probably increase as Americans move north from the Sun Belt, where climate change will be more onerous than in the Northeast. Further, the heavy draw on ground water in South Country threatens to increase salt-water intrusion into coastal towns’ wells.

In any event, making projections of global-warming effects is becoming a big industry, with many consulting firms making a good living on it, and new public programs, such as the American Climate Corps, are being created to deal with it. By the way, I noticed in The Boston Guardian the other day that that city will be updating its evacuation routes for storms and other emergencies.

The challenge has been heightened by the development of the city’s Seaport District, which is virtually at sea level, as is downtown Providence. Will the Seaport District become the Venice of the Northeast?

Hit these links:

https://turnto10.com/news/videos/federal-government-put-the-kibosh-on-big-river-reservoir

http://www.wrb.ri.gov/policy_guidelines_brmalanduse.html

https://read.thebostonguardian.com/the-boston-guardian#2023/10/06/?article=4159446

This from Reuters:

“Energy companies, hedge funds and commodity traders are stepping up their use of financial products that let them bet on the weather, as they seek to protect themselves against - or profit from - the increasingly extreme global climate.’’

See:

Getting a lift in Brattleboro

“Land Lift” (sculpture of steel, earth, grass and stone), by Bob Boemig, at the Brattleboro (Vt.) Museum & Art Center.

The museum says:

“On Sunday, Oct. 22, at 3 p.m., we're celebrating the 30th anniversary of ‘Land Lift.’

‘‘Bob Boemig's beloved sculpture graces the front of the museum. Some say it resembles a giant magic carpet, and who are we to argue? To mark the occasion, Boemig will give a talk on how ‘Land Lift’ came into being and how it relates to other public artworks he has created over the years for institutions such as the deCordova Museum, Williams College, and the Hood Museum at Dartmouth College. Admission is free and open to all. Visitors are invited to arrive early or stay late to spend time with—and on—"Land Lift," and to enjoy refreshments provided by Cai’s Dim Sum Catering.’’

David Warsh: Claudia Goldin's Nobel Prize was for many reasons

Claudia Goldin

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The award of any Nobel Prize is an invitation to go prowling through the past. In the case of Claudia Goldin, of Harvard University, born in 1946, the history on offer is that of an entire generation – not just one crucial generation, in fact, but three. Hers is the first fifty-year career by a woman in major league economic research since that of Joan Robinson (1903-1983). Perhaps not since John Nash shared the prize, in 1994, has a single life in economics been so intricately connected to the context of its times as that of Goldin.

Calling Sylvia Nasar, author of the Nash biography, A Beautiful Mind!

For one thing, Goldin is a third-generation Nobel laureate. She wrote her dissertation under the direction of economic historian Robert Fogel, of the University of Chicago, who wrote his under Simon Kuznets, of Johns Hopkins University (in Goldin’s case, with significant influence by labor theorist Gary Becker as well.)

For another, she lived the full University of Chicago experience, before escaping to a place of her own. Some years ago, she told Douglas Clement, of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, that her Cornell undergraduate mentor, Fred Kahn (who later became Jimmy Carter’s economic adviser), discouraged her from going.

“When I went to Cornell, the room that I entered was filled with paintings and good food. But Chicago was a castle, a completely different universe. I walked in and realized, once again, that I knew nothing. Now I knew absolutely nothing.… [She had gone to study industrial organization with George Stigler.] And then Gary [Becker] arrived, and once again I realized that the world of economics was much larger than I had thought. Gary was doing brilliant work on many different issues that I would call the economics of social forces. And then, to make things even better, I met Bob Fogel … [who] mesmerized me with economic history, and that combined my liberal arts junkie taste with my more rigorous math sensibilities.”

There followed twenty years of professional turbulence. After top-tier Chicago, she spent two years at third-tier Wisconsin, followed by six years in a top-ranked Princeton department, before settling down to tenure at the second-tier University of Pennsylvania. These were years when the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession was organizing, decades in which women began going to law and medical schools in significant numbers, but advances came much more slowly in economics.

Goldin’s major phase began in 1990, when she was appointed Harvard’s first tenured female professor of economics. She published Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women the same year, and was named director of the program on the Development of the American Economy of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Since then, nobody has written more thoughtfully and imaginatively about the myriad economic complexities of female gender in and out of the labor force, culminating in Career & Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity (Princeton, 2021).

There is, as well, a love story. Goldin married her fellow Harvard economist Lawrence Katz, a labor economist. Over the course of several years, the pair produced an important and heavily documented study of the rise of the high-school movement in the United States in the late 19th Century, designed to prepare workers for an emerging industrial economy. The Race between Education and Technology Society (Harvard Belknap, 2009) is routinely cited among their most enduring contributions. In most respects, Katz is not a trailing spouse; earlier this month he was elected president of the American Economic Association.

Peter Fredriksson, of the University of Uppsala, a member of the committee that recommended the prize to Goldin, described last week several years of hard work as committee members untangling one contribution from the many others that warranted recognition. In the end, he said, they settled on the combination of economic history and labor economics that produced a U-shaped portrait of the changing trade-off between careers and family. Per Kussell, professor at Stockholm University and secretary to of the committee, emphasized “The prize is not the person, it’s for the work.”

Yet in this case, the person is equally interesting. I don’t know any of the details. But I am fairly certain Goldin’s is an unusually good story. Her prize was overdetermined, in that it was awarded for many overlapping reasons. For more than a decade it was understood that it eventually would be given. Better sooner than later. It makes a fitting climax to the story of one generation and the rising of the of the next.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

So maybe secession is in order?

Fanny Kemble

“Those New England states, I do believe, will be the noblest country in the world in a little while. They will be the salvation of that very great body with a very little soul, the rest of the United States; they are the pith and the marrow, heart and core, head and spirit of that country.’’

— From British actress Fanny Kemble’s A Year of Consolation (1847)

Boston, from “The Eagle and the Wild Goose See It,’’ an 1860 photograph by James Wallace Black, was the first recorded aerial photograph.

Team player

“Portrait of Daniel King: Scouting for Men and Boys” (linocut, wood cut, lithograph), by Mark Sisson, in the group show “50/50: Collecting the Boston Printmakers,’’ at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass., through Jan. 14.

Don Morrison: As Israeli-Hamas War rages, ‘X,’ as usual, marks a spot for brazen lies; then there's Facebook ….

Don Morrison is an author, lecturer, member of The Berkshire Eagle’s Advisory Board, a commentator for NPR’s Robin Hood Radio, European editor of the British magazine Port, an ex-Time Magazine editor, and a longtime part-time resident of the Berkshires.

As war rages between Israel and Hamas, I’ve been devouring reports of the conflict from newspapers, radio and TV. Also, social media, where – according to a recent Pew Research Center survey -- nearly a third of U.S. adults now get much of their news.

But I noticed something weird. Dubious reports and images kept popping up on X, formerly known as Twitter. Some of these posts appeared to depict fighting in Gaza, complete with an Israeli helicopter being shot down.

Turns out the clips were derived from a video game and footage of old fireworks celebrations. Equally fake were alleged photos of a Hamas fighter holding a kidnapped child and of soccer star Ronaldo waving a Palestinian flag.

Those images also popped up on other sites, including Facebook, but were quickly taken down. On X, not so fast.

Much has changed since Elon Musk acquired that platform last year. Besides changing the name, he fired half the staff that polices disinformation. He also started offering Twitter’s Blue Check reliability badge to just about anybody who could pay $8 a month.

The rebranded X now gives incentive payments to users who attract large audiences, thereby increasing the volume of what sells best on social media: conflict, controversy and conspiracy. As of last week, the site started stripping the original headlines from news stories shared by users. That makes it easier to put a fake spin on real events.

Long a free-speech absolutist, Musk seems determined to make X more open to controversial views. Including his.

Shortly after taking over, he began using his personal X account (160 million followers) to criticize government COVID policies, declare war on “big media companies” and call for Ukraine to give up territory to Russia. He compared liberal Jewish investor George Soros to Magneto, Marvel’s Jewish super-villain.

That last one prompted complaints of anti-Semitism. Musk denied them, even though allowing Hamas propaganda on X does not help his case. Nor does his recent claim that the Anti-Defamation League, founded in 1913 to combat anti-Semitism, is pressuring X’s advertisers to “kill this platform.”

Which is unlikely to happen. Though X’s revenues and market value have fallen since Musk took over, its monthly active users have nearly doubled to more than 500 million. That’s a lot of influence.

In a scathing report on major social media companies last month, the European Union noted that X had the worst misinformation quotient of them all. Last week, the E.U. warned Musk that X could face penalties in Europe over its Israel-Hamas lapses.

You’ve likely never met Elon Musk, but in Walter Isaacson’s masterful new biography, Elon Musk, the South African-born billionaire comes across as a mercurial man-boy whose visionary ambitions – Reinvent the car! Colonize space! Dig tunnels under cities! – are magnets for controversy.

Isaacson’s book broke the news that Musk derailed a Ukrainian drone attack on Russian naval forces early in their conflict by declining to extend coverage of his Starlink satellite broadband network to the area of conflict.

Musk, of course, is not the only techno-overlord to cause agita. Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook came in a close second on the E.U.’s misinformation list. Jeff Bezos’ s Amazon was accused last week of directing its Alexa cloud-based device to tell users that the 2000 U.S. presidential election was “stolen by a massive amount of election fraud.” Amazon insisted that the false statement was “quickly fixed.”

Well, not exactly. Several days later, I asked Alexa about the alleged election theft. She replied: “I’m not able to answer that question.”

The power of social-media platforms remains largely unchecked. Section 230 of the federal Communications Decency Act shields them from being sued for removing – or refusing to remove – third-party content. Congressional attempts to end that protection have met with heavy industry lobbying.

I personally experienced the majesty of the social-media industry the other day. I tried to report a blatantly bogus claim – something about Hamas being financed by the Biden Administration. I was informed that X’s permissible reasons for removing a post no longer include false or misleading information.

How can we protect ourselves from this malarky? The internet is full of tips, such as: See if the story has been picked up by reputable news sites, or whether a fact-checking outfit like Snopes or Factcheck.org has weighed in on it. If the post contains a questionable photo, run a check on Google Images or Tin Eye to find its original source.

Also, get a life. I’ve been reducing my own presence on X. That means missing some personal news from family and friends, as well as Musk’s ever-entertaining comments. But I sure do have a lot of free time now.

And, in these troubling days, there’s so much else to read. Stuff that’s actually true.

Water view of history

“The American Ocean” (acrylic, collage, mixed media on canvas), from Jordan Seaberry’s show “A Historical Correction Experienced With Sight,’’ at the University of New Hampshire Museum of Art, Durham, through Dec 2. He’s a Providence-based painter, lawyer and community organizer.

Llewellyn King: As the electricity sector is reinvented, there's an urgent need for engineers and technicians to support them

At the new (founded 1997) but already highly prestigious Olin College of Engineering, in Needham, Mass.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have a soft spot for engineers and engineering. It started with my father. He called himself an engineer, even though he left school at 13 in a remote corner of Zimbabwe (then called Southern Rhodesia) and went to work in an auto repair shop.

By the time I remember his work clearly, in the 1950s, he was amazingly competent at everything he did, which was about everything that he could get to do. He could work a lathe, arc weld and acetylene weld, cut, rig, and screw.

My father used his imagination to solve problems, from finding a lost pump down a well to building a stand for a water tank that could supply several homes. He worked in steel: African termites wouldn’t allow wood to be used for external structures.

Electricity was a critical part of his sphere; installing and repairing electrical-power equipment was in his self-written brief.

Maybe that is why, for more than 50 years, I have found myself covering the electric-power industry. I have watched it struggle through the energy crisis and swing away from nuclear to coal, driven by popular feeling. I have watched natural gas, dismissed by the Carter administration as a “depleted resource,’’ roar back in the 1990s with new turbines, diminished regulation, and the vastly improved fracking technology.

Now, electricity is again a place of excitement. I have been to four important electricity conferences lately, and the word I hear everywhere about the challenges of the electricity future is “exciting.”

James Amato, vice president of Burns & McDonnell, a Kansas City, Mo.-based engineering, construction, and architecture firm that is heavily involved in all phases of the electric infrastructure, told me during an interview for the television program White House Chronicle that this is the most exciting time in supplying electricity since Thomas Edison set the whole thing in motion.

The industry, Amato explained, was in a state of complete reinvention. It must move off coal into renewables and prepare for a doubling or more of electricity demand by mid-century.

However, he also told me, “There is a major supply problem with engineers.” The colleges and universities aren’t producing enough of them, and not enough quality engineers — and he emphasized quality — are looking toward the ongoing electric revolution, which, to those involved in it, is so exhilarating and the place to be.

This problem is compounded by a wave of age retirements that is hitting the industry.

I believe that the electricity-supply system became a taken-for-granted undertaking and that talented engineers sought the glamor of the computer and defense industries.

Now, the big engineering companies are out to tell engineering school graduates that the big excitement is working on the world’s biggest machine: the U.S. electric supply system.

My late friend Ben Wattenberg, demographer, essayist, presidential speechwriter, television personality, and strategic thinker, hosted an important PBS documentary film and co-wrote a companion book, The First Measured Century: The Other Way of Looking at American History. He showed how our ability to measure changed public policy as we learned exactly about the distribution of people and who they were. Also, how we could measure things down to parts per billion in, say, water.

In my view, this is set to be the first engineered century, in tandem with being the first fully electric century. We are moving toward a new level of dependence on electricity and the myriad systems that support it. From the moment we wake, we are using electricity, and even as we sleep, electricity controls the temperature and time for us.

The new need to reduce carbon entering the atmosphere is to electrify almost everything else, primary transportation — from cars to commercial vehicles and eventually trains — but also heavy industrial uses, such as making steel and cement.

Amato said there is not only a shortage of college-educated engineers needed on the frontlines of the electric revolution but also a shortage of competent technicians or those trained in the crafts that support engineering. These are people who wield the tools, artisans across the board. In the electric utilities, there is also a need for line workers, a job that offers security, retirement, and esprit.

In the 1960s, the big engineering adventure was the space race. Today, it is the stuff that powers your coffeemaker in the morning, your cup of joe, or, you might say, your jolt of electrons.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and is based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Editor’s note: Readers should read about this Massachusetts-based company.

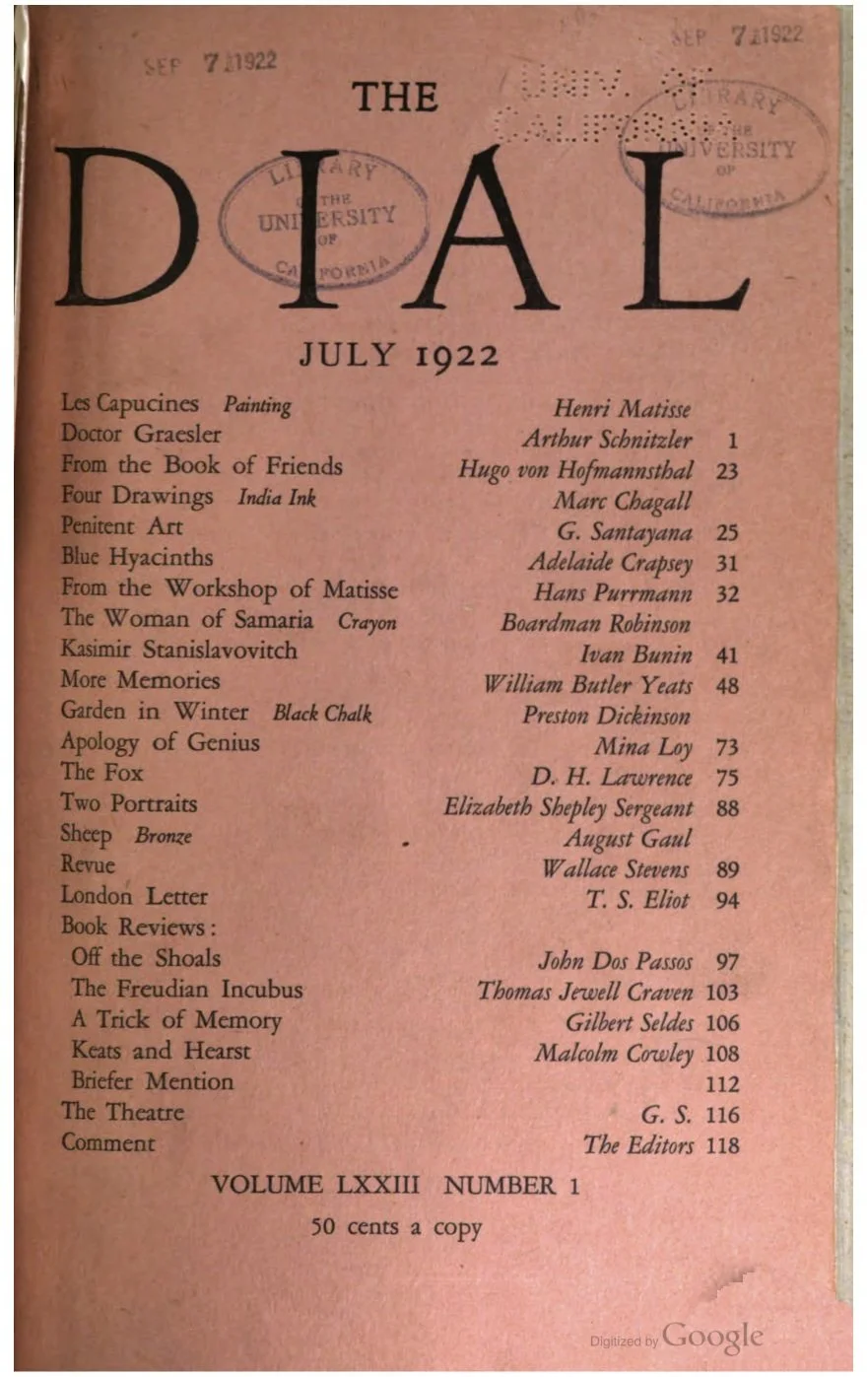

James Dempsey: In the heyday of Modernism, a memorably snippy writer-editor back-and-forth; photo correction

Alyse Gregory

Maxwell Budenheim (1891-1954)

CORRECTION: Due to an editor’s error, we misidentified a photo that had previously run with this piece as being that of Alyse Gregory. It was of Gamel Woolsey. We regret the error.

James Dempsey is the Worcester area-based author of The Court Poetry of Chaucer, Zakary’s Zombies, Murphy’s American Dream and The Tortured Life of Scofield Thayer. Research for the last is the basis of this essay. Mr. Dempsey has also served as a newspaper columnist, editor and teacher.

Maxwell Bodenheim and Alyse Gregory are two of the lesser-known names from the Modernist period. Bodenheim is undoubtedly the more notorious, thanks to a career that in the 1920s soared with exceptional promise but which, after Bodenheim’s life descended into addiction and crashing poverty, came to an end in the horrific 1954 double murder of himself and his wife, then homeless, at the hands of an unstable dishwasher they had befriended. Bodenheim was a writer of great facility who could turn his pen to poetry, fiction, and criticism, producing some two dozen books, as well as the mountain of bread-and-butter literary journalism required of the freelance writer.

Gregory was a singer, a suffragist, and a writer. The owners of the magazine The Dial, Scofield Thayer and J. Sibley Watson, urged on her the post of Managing Editor of the journal after Gilbert Seldes left the position to write what would be his most famous book, The Seven Lively Arts. She politely rebuffed them several times, not comfortable with being entrusted with so much power in the literary world of 1920’s New York City and less than confident that she could meet the magazine’s high standards.

Thayer and Watson had bought The Dial in 1919 and made of it an arts and literary magazine that attracted both avant-garde and established writers and artists. It was successful by every measure except profitability--one year it lost today’s equivalent of $1.5 million—but this was just a minor irritant to the owners, who owners, who were heirs to great wealth, Thayer to a New England textile fortune and Watson to the Western Union empire. Pay rates were generous and assured, the magazine was beautifully designed and brilliantly curated, and consequently writers and artists were eager for their work to appear in its pages. Thayer and Watson both greatly admired Gregory, and when they made made an unannounced joint appearance in her Greenwich Village apartment to importune her to edit the magazine, she finally succumbed to the pressure. She was named Managing Editor in Februry 1924 would remain at The Dial until moving with her husband, novelist Llewellyn Powys, to England the following year. During her tenure the magazine accepted work from E.E. Cummings, T.S. Eliot, D.H Lawrence, Thomas Mann, Marianne Moore, Llewelyn and T.S. Powys, Siegfried Sassoon, Bertrand Russell, Wallace Stevens, Edmund Wilson, Virginia Woolf, a nd W. B. Yeats. Artists whose work appeared included Mac Chagall, Georgia O’Keeffe, Henri Matisse, Edvard Munch, Pablo Picasso, Auguste Rodin, and John Singer Sargent

Bodenheim was well-represented in The Dial. Seven of his poems appeared in the February 1920 issue, the second under its new owners. The magazine went on to publish Bodenheim’s verse in the August 1921, March 1922, and April 1923 issues. He also published a short story in December 1921 and wrote a review of Ezra Pound’s Poems int the January 1922 issue.

Bodenheim’s own work was given two full-length reviews in the journal. In October 1922 Malcom Cowley reviewed his book of verse, Introducing Irony. Cowley sounded a touch baffled: “He writes English as if remembering some learned book of Confucian precepts.” At one point he said that Bodenheim’s “accumulation of images resembles Shakespeare,” although the reader is not sure from the context if this is intended wholly as a compliment (Bodenheim certainly took it as such). Bodenheim, Cowley wrote, is the “American prophet of the new preciosity (and with many disciples).” The critic sums up Bodenheim’s verse as “stilted, conventional to its own conventions, and formally bandaged in red tape.” He accused its author as having “all the insufferability of genius, and a very little of the genius which alone can justify it.”

In September 1924 Marianne Moore produced a long and nuanced survey of Bodenheim’s work to date with a focus on his poetry collection Against This Age and his novel Crazy Man. Moore grants Bodenheim a wide popularity but notes that “one is forced in certain instances to conclude that he is self-deceived or willingly a charlatan.” She distrusts his “concept of woman” and Bodenheim’s pronouncement “that there is zest in bagging a woman who is one’s equal in wits” is punctured by her remarking that “the possibility of bagging a superior in wits not being allowed to confuse the issue.”

Moore goes on, however, to find more than occasional felicities in Bodenheim, such as the line, “simplicity demands one gesture and men give it endless thousands.” In his stories she finds a “genuine narrator” and “an acid penetration which recalls James Joyce’s Dubliners.”

Bodenheim’s books also showed up in the magazine’s “Briefer Mention” thumbnail reviews in June and August 1923, January 1926, and August 1927.

All in all, this is a better-than-average showing in a magazine whose Contents page was populated by writers who would go on to comprise much of the 20th Century’s Western literary and artistic canon, the high priests and priestesses of Modernism.

One notes from the publication dates of Bodenheim’s work in The Dial that his writing is absent in 1924 and 1925, a period that happens to correlate with Gregory’s tenure at the magazine. This was not a coincidence. Try as he might, Bodenheim was unable to get Gregory to accept even one of his pieces. There appears to be nothing sinister about her rejection of his work; she simply did not care for it and wondered what others saw in it. She did realize, however, that Bodenheim had his admirers, and it was she who persuaded Scofield Thayer to run the review by Marianne Moore mentioned above. “I always knew you disapproved of my asking Marianne Moore to do a review of Maxwell Bodenheim’s books,” she wrote Thayer apologetically. “He is so very much a figure among certain people … that I thought he should be exposed if nothing else.”

If Bodenheim couldn’t win Gregory over, it wasn’t for want of trying. Their correspondence shows Bodenheim continually advancing on her like a big-hearted prize fighter being peppered by punches from a more technically gifted pugilist, and continuing to limply jab until he finally realizes the match is unwinnable, slumps into his corner stool, and mumbles, “No mas.”

He made his first submission, a single poem, soon after Gregory had taken up the post. She returned it, with the note below, and so set in motion an epistolary exchange that even though a century old will be familiar to both writers and editors of all ages, the one side so desperate to get the work out before the public, the other side overworked and inundated and trying not to be hardened by a job that mostly consists of rejecting.

And of course, the reality is that, unless the writer has reached a certain level in the pyramid of success, all the power is on the side of the editor. Even the word “submission’’ betrays the essential asymmetry of the relationship.

---

January 15, 1924

My dear Mr. Bodenheim,

It is very painful indeed to return a poem of yours, especially if one has been and is so very definite an admirer of your work. This one we do not wholly like, however, and so we endure the pain.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory,

Managing Editor

January 15

My dear Miss Gregory,

“It is very painful indeed to return a poem of yours, especially if one has been and is so very definite an admirer of your work. This one we do not wholly like, however, and so we endure the pain.”

Your note to me, quoted above, rouses me to a new and sad unfolding of thought. During the last two years The Dial has accepted only one poem out of sixty submitted for approval. In fact, every poem in my last two books of verse have experienced the honor or misfortune of being refused by The Dial .... If it was so very painful for the editors to return these poems, I must for the first time sympathize with their predicament, although it would seem their capacity for enduring pain has been unlimited in my case. Still, I do not like to know people have suffered with my unconscious assistance, and I am tempted to send letters of condolence to Mr. Thayer, Mr. Watson, and Mr. Burke [Kenneth Burke, an assistant editor]. However, since The Dial has published during the past two years numerous poems by E.E. Cummings. William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore, and Alfred Kreymborg, the editors of The Dial must have relieved their pain with contrasting moments of happiness. The Dial has also printed derogatory reviews of my last three books, in one of which I was accused of imitating William Shakespeare (!), and they have not seemed to indicate a very definite admiration on the part of the editors who allowed them to appear.

You must understand that this hopeless and justified sarcasm is not in any way directed at yourself. I do not know you and have no reason to doubt the sincerity of your statements. It may be indeed that you are actually a very definite admirer of my work, and I shall be happy to add you to my small band of critical friends. It is obvious, of course, that I am not a member of the clique of poets whose work The Dial has been interested in advancing, nor am I one of the smaller echoes of those poets which The Dial has published now and then. I should like to believe, however, that you are not in sympathy with this situation. I should like also to have a chat with you if your own desire is responsive.

I am enclosing two sonnets.

Quite sincerely yours,

Maxwell Bodenhiem

January 21, 1924

Dear Mr Bodenhiem:

When I said that it was painful to return a poem of yours I was speaking for myself and not for the other editors. I must confess, however, that I was not wholly aware of just how very painful such a refusal really was. Since receiving your last letter I have spent a most interesting hour going through your correspondence with The Dial for the past year or so. I am sorry indeed to appear to continue this tradition of what seems to you injustice, but nevertheless at the risk of incurring your displeasure for a second time, I am returning your two sonnets.

I should be most happy to meet you at any time.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

Managing Editor

January 24th

Dear Alyse Gregory:

Since you recently spent an interesting hour going through my correspondence with The Dial for the past two years, you may have noticed the droll ingenuity with which the editors of The Dial offered every known variety of excuse, sidestepping, polished retreat, unmeant praise, and slightly haughty restraint, to avoid any utterance of their actual preference and motives. I do not know whether their letters to me are included in your files, but my own carefully cherished collection of them will make an interesting addition to my memoirs, if I live long enough to write them. Yet, I have never charged the editors with injustice, but rather with a combination of comparative blindness, obeisance to one squad of poets only, and an invincible hypocrisy. If I am wrong, time will arrange my burial.

The poem in blank verse that I am enclosing is, to my hopelessly mesmerized eyes, beautiful and adroitly original, but, naturally, I do not expect The Dial to accept it. A second novel of mine, Crazy Man, will be issued by Harcourt Brace and Company during the coming week, and I hope that you will care to read it.

With great sincerity,

Maxwell Bodenhiem

January 25th 1924

Dear Alyse Gregory:

My publishers, Harcourt Brace and company, are mailing you a review copy of my latest novel, Crazy Man. I am hoping that you will care to review the novel yourself, simply because I have a presentiment that you would review it more fairly and seriously than the other people to whom The Dial has assigned my previous books. I need not say that I am not stooping to clumsy flattery in telling you this. I hope also, that The Dial will depart from its traditional policy toward my volumes and give the present one an early notice. Novels, alas, are materially made or discountenanced on the basis of the exact degree of immediate attention which they receive.

With great sincerity,

Maxwell Bodenheim

February 4 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

Since you seem so certain that this poem will be returned, then here it is. You allude to the “polished retreats” of The Dial. One is apt to retreat when a howling dervish with glittering eye and bared teeth advances hostilely toward one. That one can remain polished under such circumstances is proof enough of one's “sangfroid.” One only advances for combat when one really enjoys the game and one does not enjoy a game when it is one's bones which are in danger rather than one's logic.

I have considered reviewing your book myself, but I am too busy to do any writing at the present time, so I have sent it to someone who is sure to give it sensitive and sympathetic consideration.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

February 5th

My dear miss Gregory:

Alas, our correspondence seems to be proceeding along the same roads taken by that between myself and other editors of The Dial. First the expression of an admiration, disputed by the endless return of my work; then a gradual yielding to the irritation at my insistent requests or delicate, explicit, considerate frankness; then a reaction of general dismay at my “disagreeable hostility”; and finally an indifference, or an angry retirement (we have not reached this last stage yet and I hope that we never will).

You say: “one is apt to retreat when a howling dervish with glittering eye and bird teeth advances hostility toward one”. Am I really as loud and whirling as all that? Or do I merely ask (with little confidence) for a direct confession of reasons and opinions, and for the removal of those nice garments which humans hug so desperately? For instance, let us take your sentence: “since you seem so certain that this poem will be returned, then here it is”. In the case of a magazine that rejects everything that I send in might I not be excused for being almost certain of the return of any particular poem?

And should this unfortunate certainty on my part be the only reason mentioned by the editor in explanation of the failure to accept the poem? Yes, these questions are futile, but they have not been caused by a mere pugnacious attitude. I came into this somewhat over polished and secretive world of yours with hopeless desire for open and detailed expressions, and when they are freely and accurately given to me I am content, regardless of whether the person appreciates my heart and mind. I am enclosing a poem which I am almost certain that The Dial will not take. If it should be returned, I hope that you will care to [tell] me this time exactly why it was dismissed... Some day I shall drop in as your office, when I can summon enough courage to do this.

With all sincerity,

Maxwell Bodenheim

February 20 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

One must either send you a long analytical article as to one's reasons for returning your poems, or be termed evasive and hypocritical. It is hardly necessary for me to say that unique among poets and authors you ask such a thing of an editor.

Of course one returns your poems without explanation because no explanation could satisfy you.

It may interest you to know that we are expecting to have an article about your work published sometime in the near future.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

February 25th 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

It is different in the case of a poet who has his own audience and his own particular niche in modern literature, for any editor to assign specific reasons for a particular rejection. Such reasons must of necessity be negative rather than positive. One of these might be, for instance, the absence from this poem of that direct emotional or magical thrill which Milton alluded to when he said that poetry should be simple, sensuous, and passionate. This poem has intellectual weight and moral indignation. My quarrel is that it becomes written rather from the rational surface of a vigorous mind than from those deeper levels of the imagination which evoke an immediate and unequivocal response. The energetic march of your reserved and calculated metre carries the mind along with it as far as it goes, but the final impression made by the poem seems to evaporate without creating any new or original vistas of human feeling. I hope this is a definite enough explanation to make you feel that my attitude is neither evasive nor hypocritical.

You may be interested to know that we are expecting to publish before very long an article about your work. But I believe I have mentioned this in a former letter.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

March 8th

My dear miss Gregory:

Thank you. In your last letter, for the first time in three and a half years, an editor of The Dial deserted the routine of courteous, factory-made fibs and high-perched irritation, and gave me a detailed direct and human statement of motives and opinions. I had prayed with a childlike and grotesque insistence for such a miracle, and the fact that it has come almost restores my faith in God and the benevolence of statesman.

The absence of “that direct emotional or magical thrill” and that “simple, sensuous, and passionate” quality, which you mention, does not always in my opinion, mutilate the animated body of a poem. Intellect is, after all just an earthly as emotional spontaneity, and a mound of frozen earth may be just as impressive as a warmer, plant-covered hill, and you will prefer either one according to the intensity with which you value your defeated second of life. To me, life is a foul, muddled, self-lacerating, squirming, mawkishly masked, coarse, vapidly tinkling saturnalia of illusions. There is a cold fire as well as a sensuous blaze, and I am wedded to the former... I am enclosing such a fire, and will you please let me hear from you very soon?

With much sincerity,

Maxwell Bodenheim

March 18 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

This one we nearly did accept. Thank you for your most appreciative letter and I hope you will pardon me if I do not analyze our exact reasons for not publishing this present poem.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

April 3rd

My dear miss Gregory:

In your last letter of March the 18th you wrote, in regard to the rejection of a poem: “this one we nearly did accept”. I am filled with innocent wonder as to the exact boundary line between “accepting” and “nearly accepting”. Is the poem weighed upon hairs-breadth scales and found to lack an atom of weight, or is the process a broader one. In my own case, the phrase “nearly accepted”, from a magazine that practically never takes my verse, was mournfully intriguing and not quite expected. How on earth did my poetry manage to get as near as nearly in the active liking of The Dial? The poem in question, “Lynched Negro”, is better than half of the verse in all the issues of The Dial, and, in fact, its merits will probably cause other magazines to return it. I am enclosing another poem, and please let me hear from you soon. Quite sincerely yours,

Maxwell Bodenheim

April 15 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

We are sorry to return this last poem of yours.

Very sincerely yours,

Alyse Gregory

July 14th

Dear miss Gregory:

Every now and then I am possessed by an impulse to send something to The Dial. I suppose it is like dispatching an emissary to the enemy, with a platter that bears fresh fruits and shows that you are still vigorously alive. Of course, there will be no need for your answering this letter unless The Dial accepts the enclosed poem, or unless you are seized by a whim to tell me the definite actual reason for the poem’s rejection. Our correspondence at the beginning of the year petered out so gradually and naturally, down to your final, twoiline note of conventional regret, that you may be reluctant to resume it.... You told me, months ago, that The Dial has received reviews of my last two books, Crazy Man and Against This Age, and intended to print them, but I have waited in vain for their appearance. When The Dial has finished dealing with its favorites, and with easier targets, it may then decide to publish the aforeentioned reviews.

Most sincerely

Maxwell Bodenheim

July 17 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

Your urbane letter might almost tempt me to suppress entirely our review of your work. Unfortunately it is by one of our “favorites” therefore we hesitate and only slip it back in its envelope for a few more months. The real reason for not having published it sooner is that it is so much longer than our usual review that we have not been able to fit it in.

Very sincerely yours,

Alex Gregory

July 20th

My dear miss Gregory:

In your last communication you refer to the “urbane letter” which I wrote to you. If my letter was half as urbane as some of those in my prized collection of messages from The Dial editors, it must have been very smooth indeed. You tell me that the real problem for your not having published a review of my work is that the review was so much longer than your customary ones that you were unable to fit it in. In this connection, I remember a review of Ezra Pound's last book of verse which I wrote for The Dial some two or three years ago. My review is very long - 5 or 6 magazine pages in fact - but somehow The Dial managed to fit it into the very next issue, so that it would coincide with the publication of the book and be of maximum assistance to Mr Pound. Of course, there can be no valid objection to a magazine playing favorites, if it wants to, but it would be refreshing if the magazine openly admitted it and told each unlucky author: “you are not among those whose work is valued most highly, therefore you need not expect us to give you a work the same attentive and considerate if treatment which we accord to other writers”. Honestly, wouldn't that be a much better attitude to take?.

I am enclosing another excellent poem, just out of habit.

Most sincerely yours,

Maxwell Bodenheim

Writer, Novelist, and Critic

July 23rd 1924

My dear Mr Bodenheim:

You shouldn't make rejections so agreeable for one to write if you don't want to receive your things back again.

Too long a reiteration of grievances becomes at last a familiar drone that one finally disregards.

Very sincerely yours

Alyse Gregory

Managing editor

July 28th

My dear miss Gregory:

In regard to my last letter to you, you write: “too long a reiteration of grievances becomes at last a familiar drone that one finally disregards”.

The long reiteration of hedgings, apologies, sorrows, sidesteppings, and at times downright falsehoods, which I have received from The Dial editors during the past three and a half years, has been an equally familiar drone to my own sense of hearing. You also write: “you shouldn't make rejections so agreeable for me to write if you don't want to receive your things back again”. In your very first letter to me you expressed the deepest of sorrows at being forced to return my work, and if I have at least turned that sorrow into pleasure, you should be grateful to me. In persistently rejecting the best of my work for the past three years, The Dial has deprived itself of some excellent verse and prose and has played its part in depriving me of the material comfort and peace so invaluable to a creator. Perhaps The Dial’s loss has been greater than mine, and, at any rate, The Dial’s motives and tactics will be alertly judged by future eyes and ears.

In conclusion I must compliment you on being the first Dial editor who has ever given me a direct, ill-tempered affront. Since you were determined not to be quietly, good naturedly, and specifically frank -- which was all that I asked for — your sarcasm was at least more invigorating than your previous masks. Possibly, if The Dial changes managing editors at some future date, I may have an impulse to try the old experiment on your successor, but you need not fear that you will ever hear from me again.

Very truly yours

Maxwell Bodenheim

'Singing to us'

The Casco Bay Bridge, a drawbridge linking Portland and South Portland, Maine

— Photo by Rigby27

The end of Maine Route 77, which goes over the Casco Bay Bridge.

“It's all language, I am thinking

on my way over the drawbridge to South Portland,

driving into a wishbone blue, autumn sky, maple

red, aspen yellow — oaks, evergreens

stretching out in sunlight. Isn't this all

message and sign, singing to us?’’

— From “Today, the Traffic Signals All Changed for Me,’’ by Martin Steingesser (born 1937), Maine-based poet

To hear the whole poem, hit this link.

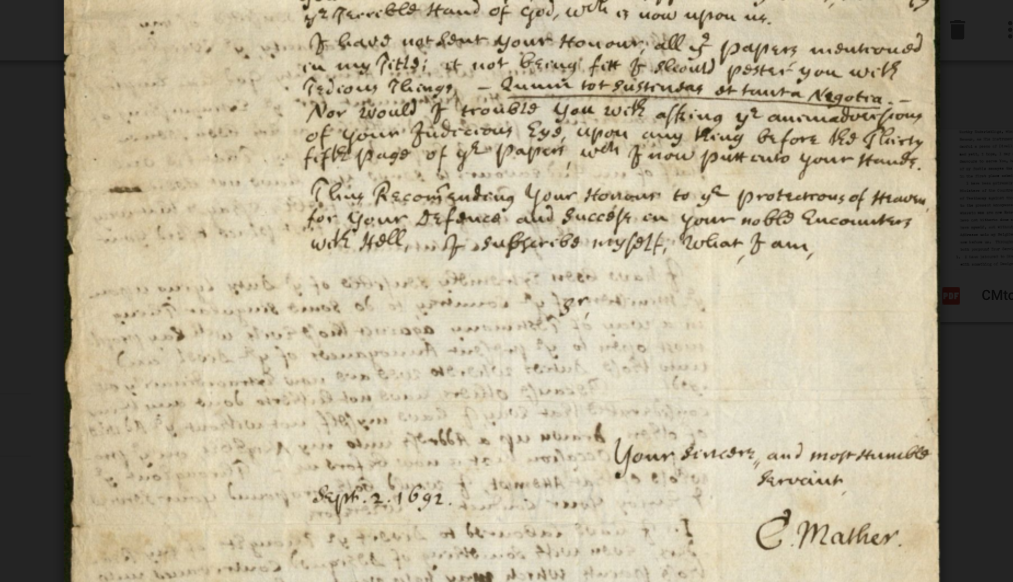

Dukes of documentation

Letter from The Rev. Cotton Mather (1663-1728) to Massachusetts Judge William Stoughton (1631-1701), dated Sept. 2, 1692

— Photo by Lewismr

Massachusetts Historical Society headquarters, Boston. It houses a treasure trove of historical New England documents

— Photo by Biruitorul

“The men who founded and governed Massachusetts and Connecticut took themselves so seriously that they kept track of everything they did for the benefit of posterity and hoarded their papers so carefully that the whole history of the United States, recounted mainly by their descendants, has often appeared to be the history of New England writ large.”

— Edmund Morgan (1916-2013), Yale history professor

Chris Powell: State police scandal seems to broaden; ‘banned books’ scam

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Announcing the retirement of his state police commissioner, James C. Rovella, and deputy commissioner, Col. Stavros Mellekas, Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont prompted speculation that the festering scandal over fake traffic tickets may turn out to be far more extensive than has been indicated.

The governor explained the departures as a matter of his wanting a "fresh start" with the state police for his second term. But his second term began nine months ago and the audit reporting many racial discrepancies with traffic tickets issued by state troopers wasn't released until five months later.

Four investigations are underway -- by the U.S. Justice Department, the U.S. Transportation Department, one commissioned by the governor and assigned to a former U.S. attorney, and one by the state police department itself. The tickets under review are suspected of misreporting the race of the motorists, thereby concealing racial discrimination by troopers. If innocent mistakes in data entry caused the discrepancies, one of those investigations might have concluded as much by now. But even the state police themselves have not provided any firm explanation.

If the misreporting was not innocent but dishonest or malicious, firings will be necessary to maintain public confidence, even as the state troopers union already has voted no confidence in the department's management while failing to provide any explanation of its own about what happened.

The audit found misreporting was probable with the tickets written by as many as 130 current or retired state troopers, so dozens of troopers might have to be dismissed or otherwise disciplined. The problem wouldn't end there, since the implication of any trooper in official dishonesty may prompt challenges to his testimony in criminal cases already decided and risk undoing them.

Additionally, as crime and traffic violations are becoming more brazen amid general social disintegration and increasing mental illness, the state police are understaffed, and dismissals or suspensions will worsen that understaffing.

Connecticut needs its police more than ever, but they are no good if they lack integrity. Integrity is their foremost qualification. If state troopers have been lacking integrity lately -- and lax discipline in some recent cases suggests as much -- solving the problem will have to go far beyond replacing the commissioner and his deputy.

xxx

Connecticut's librarians and some elected officials and advocates of using schools to indoctrinate students without their parents knowing about it recently celebrated a misnomer self-righteously: what they called Banned Books Week.

No books are banned in the United States. The recent controversies are about challenges to books in school and public libraries and school curriculums -- whether certain books, especially those of a sexual nature, are appropriate for certain ages or appropriate for stocking in a school or public library at all.

Appropriateness is always a matter of judgment and thus always a fair issue. While some challenges may be crazy or bigoted, the real issue is always whether in a democracy the public has the right to express its judgment on the management of public institutions and to seek to have that judgment implemented through elected officials, or whether librarians and school administrators are always right and must not be questioned.

But addressing the real issue candidly would diminish the power of the people in charge by legitimizing questions about their judgment. So instead the people in charge frame the issue as that of "banning" books, since banning books is plainly fascism and commands little support.

Of course dismissing the public's concerns about the operation of public institutions is fascism too, but now that Connecticut is run by the political left, fascism is thought to be impossible here.]

The irony is that if keeping a book out of a library or curriculum is "banning" it, librarians and school administrators themselves are the biggest book banners. For libraries and curriculums are usually very small while the supply of books is virtually infinite, so librarians and school administrators are always having to choose against millions of books, including some pretty good ones.

What vindicates their choices? That's what Banned Books Week is for.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Drinking water under threat

EPA drinking water security poster from 2003.

From article by Frank Carini in ecoRI News

The oceans aren’t the only waters taking a beating at the hands of the most common and widespread species of primate on the planet. The elixir that sustains life is constantly abused and foolishly taken for granted by Homo sapiens.

When it comes to drinking water, climate pressures (most of which are caused by humans) and human idiocy apply an immense amount of pressure. The faucet is leaking. The dam is close to bursting.

More frequent and heavy rains are threatening drinking-water sources. Stormwater runoff and floodwaters are washing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, sewer overflows, and nutrients, mainly nitrogen and phosphorous from overfertilized lands, into reservoirs. The taxpayer/ratepayer cost to treat these perverted sources continues to rise.

The creep of seawater — thanks to sea-level rise and storm surge that is reaching further inland — into private wells and freshwater aquifers is a growing problem for coastal states, including the Ocean State. Prolonged drought and relentless development are forcing the pumping of more groundwater, which further impacts already stressed aquifers and private wells. It’s a vicious cycle that begins and ends with the burning of fossil fuels.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

‘Antique fragments’

“Heading North” (wood, cooper, acrylics, antique fragments), by Mary Ellen Flinn, in the show “Folks and Fables,’’ at the Dartmouth Cultural Cener, in the village of Padanaram, through Nov 4.

— Photo Courtesy: Artist.

The center explains that the show showcases new work from a collaboration of Don Cadoret and Mary Ellen Flinn. It includes Cadoret's colorful and detailed “Story Paintings” and Flinn's carved and assembled sculptures. Both artists "are self-taught and inspired by the antique fragments and frames of our past."

The Padanaram Bridge, leading to the village of Padanaram, in Dartmouth..

— Photo by ToddC4176

But no giant pumpkins (Copy)

“Southwark Fair” (1737), (etching and engraving), by William Hogarth (1697-1764, British), in the show “Prints and People Before Photography, 1490-1825 ,’’ at the William Benton Museum of Art at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, through Dec. 17.

The museum says:

“The arrival of printmaking in early modern Europe led to new possibilities for mass communication and art collecting. Transportable, reproducible, and relatively inexpensive, prints contributed to the exchange of knowledge and ideas across international borders and among social classes. Prior to the invention of photography, it was prints that provided a window on the world, circulating images of other works of art, distinguished people, and noteworthy places and events. ‘‘