Soothing wave action

“Jerri” (oil on canvas), by Kathleen Jacobs, on the show “Making Their Mark: 7 Women in Abstraction,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, Greenwich, Conn., Sept. 21-Nov. 4

“Artist's Home in Autumn, Greenwich, Connecticut’’ (c. 1895), by John Henry Twachtman

Marjorie Kelly: Fearsome ‘financialization’ drags down America

— Photo by Ingfbruno

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

It’s been been 15 years since the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

The investment firm’s startling downfall marked the beginning of a historic Wall Street crash that swiftly wiped out over $7 trillion in home equity and $2.8 trillion in retirement portfolios.

Wall Street hasn’t fundamentally changed its behavior. Since then, Big Finance has engineered an even more entrenched system of creating wealth mostly for the ultra-rich while spinning out crisis after crisis for the rest of us.

That system has led to insecure, low-wage contract jobs replacing stable work, staggering debt mounting for college graduates, and monopolies crushing family businesses. It’s entrenched a political system captured by billionaires and huge corporations and left society struggling to meet the challenge of climate change.

This anniversary is an opportunity to take a step back and look at the overarching problem here: “financialization.” While we used to have an economy that manufactured stuff, now it manufactures debt.

Before 2008, big banks financialized mortgages. Now they’re financializing houses, buying up single family homes and charging high rents, scrimping on maintenance, and pursuing aggressive evictions.

The same is happening from health care to the local news, as private equity firms buy up vital businesses, cut staff and services to pad profits, and then sell their assets for scrap when the businesses predictably fail.

The latest Wall Street game is to turn the planet into a new asset class, creating “natural asset companies” to monetize “ecosystem services” from water, forests, coral reefs and farms.

What drives financialization is what I call “wealth supremacy” — a bias ingrained in our economic system that tells us wealthy people matter most. It suggests the core aim of our economy should be delivering ever-increasing gains to their investment portfolios.

This bias is embodied in a series of myths. There’s the myth that no amount of wealth is ever enough. Another is that only shareholders and executives should have a say in corporations, while workers are disenfranchised and dispossessed.

Then there’s the myth of the free market, which tells us corporations and capital must be able to move freely throughout the world, while the freedom of people — democracy — must be subordinated.

Recognizing wealth supremacy helps us see our task: to build an economic system designed not for maximum investment returns, but for life to flourish. My organization, the Democracy Collaborative, calls it a “democratic economy” — and it’s rising all around us.

For starters, corporations don’t have to be owned by shareholders or executives. They can be owned by workers themselves.

Already workers in the U.S. own some 6,000 companies. Employees at worker-owned companies like the New York City-based Cooperative Home Care Associates and the San Francisco-based waste disposal and recycling company Recology enjoy more stable jobs and double the retirement savings of employees at conventional firms.

Nor do big banks need to do all the banking.

Roughly 1,000 community development financial institutions provide fair loans to marginalized communities typically shunned by Wall Street banks. For example, River City Credit Union in San Antonio, Texas helps immigrants set up bank accounts so they don’t have to rely on predatory payday lenders and check-cashing storefronts.

And what if more of us owned our utilities?

Eighty-five percent of Americans already get their water from public utilities instead of for-profit companies. Now there’s a growing movement from Ann Arbor, Mich., to Maine and New York for publicly and cooperatively owned energy utilities. Such companies could be more willing than for-profit utilities to transition quickly from fossil fuels and make investments to prevent sparking wildfires.

The models and pathways we need exist around us. But making the rapid, systemic change we need requires letting go of the myth that wealth-maximizing capitalism is the only system possible.

It’s not. And if we want to keep our society standing, we need to topple wealth supremacy.

Marjorie Kelly is Distinguished Senior Fellow at The Democracy Collaborative and an advisory committee member of Massachusetts Public Banking. Her new book is Wealth Supremacy: How the Extractive Economy and the Biased Rules of Capitalism Drive Today’s Crises.

Will Morgan: A mystery photo and missing memory

Half a dozen years ago, our current president published a book about his son’s death from glioblastoma. Titled Promise Me, Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship, and Purpose, started with Beau Biden’s plea to his father not to let grief overcome him. (The loss of the Delaware senator’s wife and daughter in a car accident in 1972 almost derailed Biden’s life, including his political career.)

I found an autographed copy of the book, simply inscribed “Joe Biden,’’ in Savers in Boston’s West Roxbury for $4.49. The forgotten best seller did, nevertheless, offer a treasure, the mystery photo above.

There are almost no clues as to the identity of this young girl and, presumably, her younger brother. It’s printed on Kodak Xtralife II paper, but who uses prints in this age of computers and online libraries? The buildings look recent – faux Georgian – although the cobblestone street could be European.

Looking at the lass’s auburn hair and complexion, we could guess that these children are Irish.

There’s a story here, at least in our imaginations. But, promise me, Dad, that you will date your photos and tell us why images like this represent a memory worth keeping.

An architectural and photo historian, William Morgan is a frequent contributor to New England Diary. His latest book, Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, will be published in October.

John O. Harney: My new parcels of volunteer life

The author overseeng coneflowers at the Rose Kennedy Greenway

Inspired by the story of George Orwell caring for his roses while writing masterpiece essays, I looked forward to a retirement spent partly watching over the plants on Boston’s Rose Kennedy Greenway. Sure, I got a bit stressed over whether the fading white blooms I saw were Virginia Sweetspire Itea Virginica or Witch Alder Fothergilla. As I had earlier over whether the purple perennials were Salvia or Veronica. But for the most part, my most stressful dilemma would be choosing which dim sum joint to hit near the Greenway’s Chinatown “parcel.”

As for my own essays, never brilliant like Orwell’s, they’ve slowed to a crawl since the beginning of this year, when after 30-plus years, I left the editorship of The New England Journal of Higher Education and began volunteering in phenology at the Greenway. (Regrettably, I may have planted a kiss of death on the journal, where you’ll see few new postings since my departure.)

Fearing America’s increasing flirtations with nationalism and Us vs. Them politics, I also began volunteering in English language teaching at the Immigrant Learning Center, in Malden, Mass.

On the Greenway

Early on, a Greenway staff member gave me her cell number in case I needed help ID’ing plants or, she quipped, if I needed to report anything unusual on the Greenway, “like a body.” A staffer mentioned during an earlier volunteer pruning day, “the Greenway is enjoyed by all kinds of people so watch out for needles as you clean up around plants.”

Then Greenway retirement gig also reminded of my work days, attending economic conferences at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, directly across the street from Parcel 22. That Dewey Square stretch of gardens was then housing Boston’s version of the Occupy Wall Street movement. (Sometimes, feeling out of place in my ill-fitting suit, I wished that I was helping their cause rather than returning to my office.) By now, though, the whiff of rebellion had yielded to a riot of pink and white Coneflowers Echinacea and a Boxwoody imperial fragrance in the parcel near the Fed.

Sunflowers on the Greenway

Earlier in the summer, the Greenway folks worked with local nonprofit groups from Roxbury to plant massive stands of Sunflowers, the unofficial flower of my daughter-in-law’s war-torn Ukraine. In August, the Sunflowers bloomed gloriously around the vent and mural on Parcel 22. But more recently, it looked like some force had crashed into the middle of the main patch, pushing the Sunflower stocks outward like the Tunguska event in Siberia.

Nearby, I’m fascinated by the Pawpaw tree because of my childhood memory of a nursery rhyme that went: “Where, oh where oh where is Johnny [personalized for me], way down yonder in the Pawpaw patch.”

I’m also drawn to the paver my kids and I placed at the corner of Milk Street for my wife, saying “Joanne Harney We Love You.” I still check on the paver when I go to visit my “parcels.” And it looks sharp, as if a good angel has been coming along and buffing it. A half-joke in my house was that we could all meet there in case of disaster (though the urban location 500 feet or so from a rising sea may not be a safe haven forever).

I am also heartened by the Greenway’s small steps in food equity. In the edible garden, a sign reads:

ATTENTION GARDEN VISITORS: Please help us share the harvest!

The produce grown here is specifically cultivated and donated to our local homeless shelters.

Kindly refrain from picking the food to ensure it reaches those in need.

Your cooperation will help us make a difference in our community.

I’ve noted the ferny asparagus and carrots as well as strong corn and tomatillos. One day, a woman emerged from near a small houseless encampment and asked me if there was any mint in the garden. I said I thought there was some in Parcel 22, to which, she seemed relieved, saying that her husband, who camps out with her, eats it from time to time. A staffer suggested some of the Milkweeds in the gardens were planted secretly by visitors hoping to encourage Monarch Butterflies on the Greenway.

Ricinus

But I assume all know the stay clear of the purplish-leaved Ricinus growing in a galvanized bucket on Parcel 22 … host of the castor bean but also of famously deadly ricin.

My confines became Pearl, Congress and Purchase streets and Atlantic Avenue. The key reference points in my geographic descriptions were: the restaurant Trade, the Brazilian consulate with its national flag, the Native American Land Acknowledgment, the various Greenway maintenance sheds (and hangouts for the houseless), the Fed, the Red Line plaza, the Purchase Street tunnel (a reminder that the Greenway sits just a matter of a few feet over an interstate highway) and my favorite landmark, the Japanese Umbrella Pine in Parcel 21.

At the Immigrant Learning Center

Given America’s xenophobia, I also wanted to use my newly found time to help marginalized people in immigrant communities. I had tried to cover their predicament editorially in the journal. But retirement brought a new commitment. Reasoning that my decades of editing was something like teaching English, I applied for volunteer teaching of adults at the Immigrant Learning Center.

It has been a great pleasure to work with new immigrants from Haiti, Vietnam, China, Syria, Rwanda and elsewhere. When I helped one Syrian student read a children’s book about Winnie the Pooh, the description of the One Hundred Acre Wood reminded me of the Greenway work.

Many of the countries of origin of students at the center share a history of exploitation by the U.S., where these innocents fervently want to settle.

I have covered a few subjects probably too subtly for non-English speakers. Holidays, for example. I explained that Memorial Day was a day to remember people who had died. Sure, it was originally people who died in wars, but really anyone who’s died. Back to my old view that people who resisted the Vietnam War were as worthy of honor on Veterans Day as those who served.

Of Juneteenth, I tried to explain that while Americans say that they believe all are created equal, the concept of slavery clearly ran counter to that. And I reminded the many Haitians in the class that Haiti was among the many countries that abolished slavery before the U.S. I also mentioned to the Haitian students that I was rooting for the Haiti women’s national soccer team in the World Cup. To which, I was asked to explain the meaning of “rooting for.”

The immigrant lessons also teach much about the U.S. economy. One exercise focuses on occupations such as dishwasher, house cleaner, delivery driver and “manager.” One student noted getting a pay raise of 50 cents per hour—a modest honor. In one lesson, my lead teacher, himself a Haitian immigrant, drilled students on the difference between odd from even numbers … somewhat unimportant I thought until he noted smartly that Americans increasingly were getting shot knocking on the wrong doors.

Too much analytics

My aversion to analytics—clearly taking over the worlds of higher education and journalism that I recently fled—hobbles me even in volunteer life.

The Greenway folks prefer describing bloom progress with number rankings rather than comments. To make matters worse, the rankings are not the usual, 1 is best and 5 is worst, or vice versa. Instead, 3 is the best. It is peak flowering, then 4 is much less and 5 about done. 1 signifies just starting to bloom and 2 is progressing. Even an amateur like me can take a stab at peak flowering, but discriminating between 1 and 2 and between 4 and 5 is much tougher. And what to think of the Lamb’s Ear whose foliage graced two large banks in Parcel 21 but only shot out one flower on my watch.

The ranking snafu is familiar to anyone pestered by evaluation requests whenever you buy a product or service these days. As a former writer and editor, I’m happier with my rough notes than my arbitrary rankings.

I tell myself I may be a small part of a grand repository of plant info, or at least some effort to introduce identifying plant tags, which the Greenway lacks. Or an “interactive bloom tracker,” which sees to be always out of order when I try it. Of course, the data may be going into a black hole. But for me, the exercise is worth it.

The immigration educators understandably discourage use of synonyms, puns and anecdotes that may just confuse new English learners. All tough for a guy who considered himself “thoughtful,” but may have really been “wordy” and “unfocused.”

Bravery and bathos

“Intrepid” (oil on masonite), by Lyndeborough, N.H.-based artist Susan Q. Brown, at the Conant Gallery at Lawrence Academy, Groton, Mass.

Her Web site says:

Her Web site says her figurative and abstract work … evokes the natural landscape and human forms to explore separation and interconnectedness using color, grids, and unexpected imagery that viscerally stimulates the viewer to perceive/experience something new to them. While Susan works from her impressions of the natural world, she also draws upon pillars of art history, such as ancient works by Buddhist and Indian artists in the East and Western contemporary masters like Agnes Martin and Hilma af Klint.’’

Lyndeborough Town Hall, built in 1846

Our ‘precarious place’

“In the Wind ‘‘ (oil, acrylic and collage on stretched canvas), by Anne Sargent Walker, in her show “Out on a Limb,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Oct. 4-29

She says:

“My mixed media paintings explore the beauty, complexity and fragility of the natural world and our complicated relationship with it. The surface content of birds, flora and other creatures often degrades, peels back, dissolves or drips to reveal layers underneath, suggesting the planet’s warming, loss of habitat, species, the earth itself and of course us.

‘‘‘Out on a Limb’ refers to the precarious place we have arrived at. Mass extinction of species is at hand. Invasive species threaten our landscapes, A warming climate is making habitat for both humans and animals unlivable. There is good news too, but we must make changes now.’’

'Hope and trust'

Portsmouth Harbor Lighthouse is a historic lighthouse within Fort Constitution, in New Castle, N.H., now best known as a rich summer-resort town.

“Lighthouses, from ancient times, have fascinated and intrigued members of the human race. There is something about a lighted beacon that suggests hope and trust and appeals to the better instincts of mankind.’’

— Edward Rowe Snow (1902-1982), New England coastal historian, in his book Famous Lighthouses of New England (1945)

David Warsh: Secular time and political time

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

So Joe Biden is sticking with his bid for a second term. Labor Day was the president’s last chance to bow out. I expect Biden to win. Get ready for the hardest four years in the White House since Lyndon Johnson lived there, 1965-1969.

That is the implication of a view of American history as a recurring sequence of lengthy political change: breakthroughs, followed by breakups, followed by breakdowns. Over the years, there have been all kinds of cycle theories about U.S. political change. An unusually fully-elaborated version is associated with Yale theorist Stephen Skowronek.

Skowronek distinguishes between what he calls secular time and political time. The latter is time in the system, the medium through which presidents must reckon with commitments their predecessors have made. Secular means the president’s own time in office, for better or worse. Since presidential leadership is what organizers, journalists, and voters care about, secular time is the way our clocks tick.

Thus five major systems, described by their ideological commitments and coalition support, have unfolded in the years since the American Civil War: the presidencies of Abraham Lincoln to Grover Cleveland, 1861- 1897; William McKinley to Herbert Hoover, 1897-1933; Franklin Roosevelt to Lyndon Johnson, 1933-1968, Richard Nixon to George H.W. Bush, 1969-93; and Bill Clinton to Joe Biden, 1993-2025.

Underneath all this is the machinery of constitutional democracy, which is manipulated by actors to determine the outcomes: the federal system, with its regional governments; the three branches of national government, with their various checks and balances; the coalitions of interests, old and new, that constantly shift back and forth; and, finally, “presidential definition” in public opinion, a concept more elusive than the rest.

What enables a president to set an agenda that lasts thirty years?

Luck and timing, of course. There may be a sense that “it’s time for a change.” If a candidacy succeeds, gradually choices are made. These may meet with success among voters. If they do, a two-term president’s successors are constrained. Otherwise, a one-term president goes home.

In Clinton’s case, “presidential definition” turned on his decisions to balance the budget, ignore China and to expand NATO to the borders of Russia. Presidents since then have paid less attention to the budget constraint, continued to cooperate with China in varying degrees, but they have continued to attempt to expand NATO, which has led to the war in Ukraine.

Much of this happened on Barack Obama’s watch, when Hillary Clinton and John Kerry, two failed presidential candidates, served successively as secretary of state. Donald Trump’s presidency led to four years of vamping, thanks to his conflicts with both Russian and Ukrainian interests. Then Biden, who as vice president oversaw Ukrainian policy for eight years as vice president, as president promoted his team of advisers and pressed ahead. It is his war to win, or, more likely, to lose.

So, after the thirty years that began with the election of Bill Clinton, Biden is probably a breakdown president,. His age is a problem. There is his relationship with his son Hunter. “Bidenomics” offers little hope of coming to grips with America’s looming fiscal crisis.

What next? Forget about Trump. I expect a traditional Republican candidate to emerge from the embers of Biden’s presidency, as Lincoln emerged from the ashes of James Buchanan’s single term in office, to end the Andrew Jackson-Buchanan system, 1832-1861 and found the modern GOP. Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin, an up-to-date version of former GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney, is the most obvious possibility today, but things will shift around a good deal in the next five years.

By 2028, climate change and fiscal crisis probably will be the central issues, replacing the war in Ukraine, threats to Taiwan and the composition of Trump’s Supreme court. Mitch McConnell, Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas will matter less. The rising generations will matter more.

How to follow developments? Continue to read the four great English-language newspapers – The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. The long swings will continue. America will be all right.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com.

The sense of ‘nowness’

“Between Gatsby and Clue’’ (oil painting detail), by Lakeville, Mass.-based painter Joseph Fontinha, in his joint show, “Everywhen,’’ with Tatiana Flis, at Fountain Street Gallery, Boston, through Oct. 1.

The gallery says he:

“{W}orks to have each mark in a painting carry its thematic content. This quality draws the viewer into the moment being portrayed with all of its energy and physicality. This sense of ‘nowness’ points to the many possibilities inherent in every moment. Fontinha is intentional about conveying truths that he feels can only be communicated through oil paint. Unlike the highly negotiated spaces captured in his videos and interactive installations, his paintings focus on the standardization of perception. This opportunity to detangle images through durational viewing allows for a deep and resonant experience.’’

Assawompset Pond, in Lakeville.

— Photo by ToddC4176

Elisabeth Rosenthal: Primary- care crisis intensifies

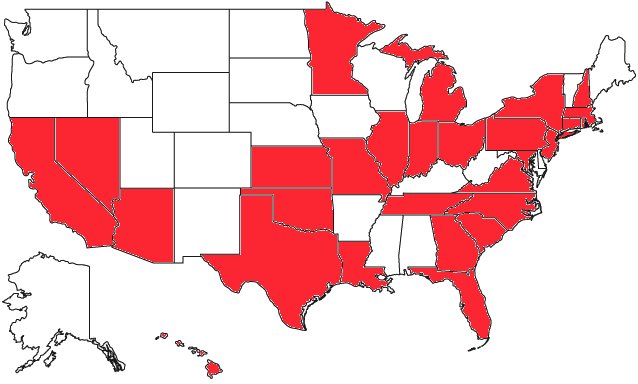

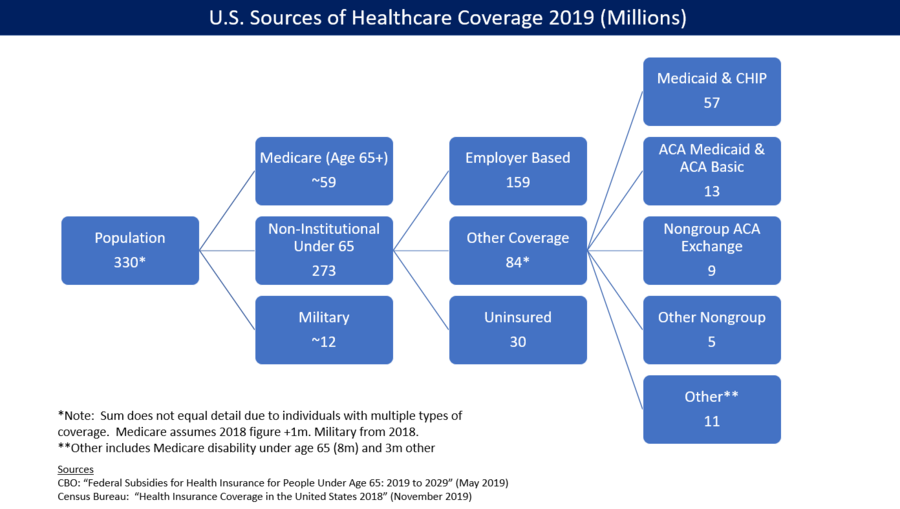

These measurements of health-care service levels for specific areas of the U.S. came out in June 2020 through the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

States in red have Rhode Island-based CVS’s Minute Clinics, which are cutting into traditional primary-care practices.

“We have a specialty-driven system. Primary care is seen as a thankless, undesirable backwater.”

— Michael L. Barnett, M.D., health-systems researcher and primary-care physician in the Harvard Medical School system

I’ve been receiving an escalating stream of panicked emails from people telling me their longtime physician was retiring, was no longer taking their insurance, or had gone concierge and would no longer see them unless they ponied up a hefty annual fee. They have said that they couldn’t find another primary-care doctor who could take them on or who offered a new-patient appointment sooner than months away.

Their individual stories reflect a larger reality: American physicians have been abandoning traditional primary- care practice — internal and family medicine — in large numbers. Those who remain are working fewer hours. And fewer medical students are choosing a field that once attracted some of the best and brightest because of its diagnostic challenges and the emotional gratification of deep relationships with patients.

The percentage of U.S. doctors in adult primary care has been declining for years and is now about 25 percent — a tipping point beyond which many Americans won’t be able to find a family doctor at all.

Already, more than 100 million Americans don’t have usual access to primary care, a number that has nearly doubled since 2014. One reason our coronavirus vaccination rates were low compared with those in countries such as China, France, and Japan could be because so many of us no longer regularly see a familiar doctor we trust.

Another telling statistic: In 1980, 62 percent of doctor’s visits for adults 65 and older were for primary care and 38 percent were for specialists, according to Michael L. Barnett, a health-systems researcher and primary- care doctor in the Harvard Medical School system. By 2013, that ratio had exactly flipped and has likely “only gotten worse,” he said, noting sadly: “We have a specialty-driven system. Primary care is seen as a thankless, undesirable backwater.” That’s “tragic,” in his words — studies show that a strong foundation of primary care yields better health outcomes overall, greater equity in health-care access, and lower per-capita health costs.

One explanation for the disappearing primary-care doctor is financial. The payment structure in the U.S. health system has long rewarded surgeries and procedures while shortchanging the diagnostic, prescriptive and preventive work that is the province of primary care. Furthermore, the traditionally independent doctors in this field have little power to negotiate sustainable payments with the mammoth insurers in the U.S. market.

Faced with this situation, many independent primary-care doctors have sold their practices to health systems or commercial management chains (some private-equity-owned) so that, today, three-quarters of doctors are now employees of those outfits.

One of them was Bob Morrow, who practiced for decades in the Bronx. For a typical visit, he was most recently paid about $80 if the patient had Medicare, with its fixed-fee schedule. Commercial insurers paid significantly less. He just wasn’t making enough to pay the bills, which included salaries of three employees, including a nurse practitioner. “I tried not to pay too much attention to money for four or five years — to keep my eye on my patients and not the bottom line,” he said by phone from his former office, as workers carted away old charts for shredding.

He finally gave up and sold his practice last year to a company that took over scheduling, billing and negotiations with insurers. It agreed to pay him a salary and to provide support staff as well as supplies and equipment.

The outcome: Calls to his office were routed to a call center overseas, and patients with questions or complaining of symptoms were often directed to a nearby urgent care center owned by the company — which is typically more expensive than an office visit. His office staff was replaced by a skeleton crew that didn’t include a nurse or skilled worker to take blood pressure or handle requests for prescription refills. He was booked with patients every eight to 10 minutes.

He discovered that the company was calling some patients and recommending expensive tests — such as vascular studies or an abdominal ultrasound — that he did not believe they needed.

He retired in January. “I couldn’t stand it,” he said. “It wasn’t how I was taught to practice.”

Of course, not every practice sale ends with such unhappy results, and some work out well.

But the dispirited feeling that drives doctors away from primary care has to do with far more than money. It’s a lack of respect for nonspecialists. It’s the rising pressure to see and bill more patients: Employed doctors often coordinate the care of as many as 2,000 people, many of whom have multiple problems.

And it’s the lack of assistance. Profitable centers such as orthopedic and gastroenterology clinics usually have a phalanx of support staff. Primary-care clinics run close to the bone.

“You are squeezed from all sides,” said Barnett.

Many ventures are rushing in to fill the primary-care gap. There had been hope that nurse practitioners and physician assistants might help fill some holes, but data shows that they, too, increasingly favor specialty practice. Meanwhile, urgent-care clinics are popping up like mushrooms. So are primary-care chains such as One Medical, now owned by Amazon. Dollar General, Walmart, Target, CVS Health and Walgreens have opened “retail clinics” in their stores.

Rapid-fire visits with a rotating cast of doctors, nurses, or physician assistants might be fine for a sprained ankle or strep throat. But they will not replace a physician who tells you to get preventive tests and keeps tabs on your blood pressure and cholesterol — the doctor who knows your health history and has the time to figure out whether the pain in your shoulder is from your basketball game, an aneurysm, or a clogged artery in your heart.

Some relatively simple solutions are available, if we care enough about supporting this foundational part of a good medical system. Hospitals and commercial groups could invest some of the money they earn by replacing hips and knees to support primary care staffing; giving these doctors more face time with their patients would be good for their customers’ health and loyalty if not (always) the bottom line.

Reimbursement for primary-care visits could be increased to reflect their value — perhaps by enacting a national primary care fee schedule, so these doctors won’t have to butt heads with insurers. And policymakers could consider forgiving the medical school debt of doctors who choose primary care as a profession.

They deserve support that allows them to do what they were trained to do: diagnosing, treating, and getting to know their patients.

The United States already ranks last among wealthy countries in certain health outcomes. The average life span in America is decreasing, even as it increases in many other countries. If we fail to address the primary care shortage, our country’s health will be even worse for it.

Elisabeth Rosenthal is a KFF Health News reporter.

Elisabeth Rosenthal: erosenthal@kff.org, @RosenthalHealth

‘She lights her fire’

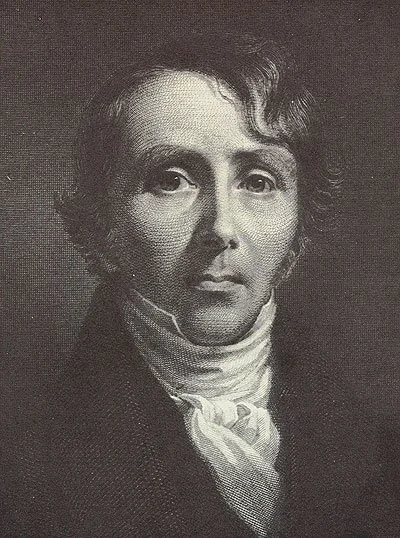

William Ellery Channing

“I sing New England, as she lights her fire

In every Prairie’s midst; and where the bright

Enchanting stars shine pure through Southern night,

She still is there, the guardian on the tower,

To open for the world a purer hour.”

― William Ellery Channing (1780-1842), Boston-based Unitarian minister and theologian. Late in life he became an avid abolitionist. For many years, he was the minister at the now-long-gone Federal Street Church.

Federal Street Church, built in 1809

Art inflation

From Claire Ashley’s show “Radiant Beasts,’’ at the Lamont Gallery, at Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, N.H., through Nov. 18

The gallery explains:

‘Claire Ashley’s large-scale inflatables explode the possibilities of painting. Her practice devours the traditional mediums of sculpture, installation, painting, and costume, spitting back hybrid ‘bodies’ that are moveable, wearable, and deliciously preposterous. Made from PVC-coated canvas tarps, spray paint, and small blower fans, Ashley’s work is a complex, humorous mash-up of fine art meets bouncy house.

“The artist resists and pushes against the traditional norms of painting, disrupting the straight edges and flat, fixed nature of the discipline by creating bulbous, malleable inflatables that alter themselves to fit new environments. Displayed as site-conscious interventions that shape shift as they playfully wedge into and squish between architectural spaces, this exhibition expands beyond the walls of Lamont Gallery. Ashley’s monumentally scaled works emerge inside academic buildings and spill out onto campus, surprising the viewer and prompting questions such as, what the object is, how it appeared, and where it came from.’’

Chris Powell: Government and other villains in Conn'.s medical-insurance price surge

Logo for Connecticut’s health-insurance marketplace

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Who and what are to blame for the soaring cost of medical insurance in Connecticut? A couple of weeks ago, a hearing held by the state Insurance Department heard opinions in response to more requests from medical insurers for premium increases, this time averaging 20 percent for individual policies and 15 percent for small group plans.

Of course, the country's general inflation rate is a big part of the problem. But the costs of medical insurance are especially complicated, since for many years government's intervention, necessary as it may be, has turned medicine into a carnival of cost-shifting, so much so that people can hardly know the real cost of what they're getting and who is really paying.

Elected officials blame insurers, who blame hospitals and doctors, who blame insurers and government. They're all correct, though exactly how much each is to blame isn't clear.

But start with government because of its direct accountability to the public and because government is the biggest purchaser of medical insurance -- for its employees, for the poor via Medicaid and for the elderly via Medicare.

Government's payments for Medicaid and Medicare patients are sharply discounted from rates paid by other patients. The point of this discounting was to shift costs to those other patients and hide them. Exactly how much costs are shifted is debated. But if government paid more for the poor and elderly, hospitals and doctors could charge other patients less and insurers could reduce their rates -- at least theoretically.

But saving money in medicine and medical insurance may require competitive markets even as those sectors have greatly consolidated.

Most Connecticut hospitals are now owned by two chains -- Hartford HealthCare and Yale New Haven Health -- and hospitals have been acquiring or partnering with physician practices, further diminishing competition. This consolidation has been attributed to the growing burden of government regulation and the desire of doctors to do less paperwork and more patient care.

Meanwhile, insurance companies have merged and gotten bigger or left the medical insurance business. Only three insurers are selling individual medical policies on Connecticut’s Affordable Care Act exchange in Connecticut, and one insurer has reported big losses in the last two years. That company may not be looting its customers as much as the haters of insurance companies like to believe. But if medical insurers really have excess profits, government could always tax them away.

How hard are medical insurers negotiating with hospitals and doctors? At the recent hearing, state Atty. Gen. William Tong complained that insurers are not negotiating costs but rather building their rates on mere estimates of annual cost increases. Presumably state law could require insurers to seek specific rates from hospitals and physicians for a year or two in advance, if hospitals and physicians were willing and able to provide them and stick to them. They're probably not.

Also driving up medical-insurance costs are state government mandates for coverage that insurers must provide. Not all are necessities. Many are mainly matters of legislators seeking to gratify one constituency or another. Could state government reduce its medical insurance mandates? Not without a lot of shrieking.

(Meanwhile, state government's medical insurance for its employees and retirees spends $1 million a year for erectile -dysfunction drugs.)

Maybe the best suggestion at thd hearing was made by state government's departing health-care advocate, Ted Doolittle, who said that insurance companies are serving as a "stalking horse for the hospitals," the biggest parties in interest. Doolittle said hospitals should be interrogated just as closely as insurers and the hospitals raising costs most should be identified.

There's a lot of money in medicine and insurance, with many executives paid spectacular salaries, and the search for medical and medical-insurance coverage efficiencies is a largely political matter. So it should be the General Assembly's job more than the Insurance Department's.

Indeed, for just presiding over soaring medical-insurance costs, government is most to blame for them. But then, which legislators have the courage to risk offending not just two huge industries but also their many constituents who are patients?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net.)

Frank Carini: In search of dragons and damsels

Dragonflies during migration

— Photo by Shyamal

From ecoRI.org

SOUTH KINGSTOWN, R.I. — Virginia Brown and Nina Briggs have been hunting dragons for three decades. They have spotted thousands. Capturing one is a bit more difficult. They can be up in a tree out of reach or hidden in leaf litter below. Catching one by hand is toilsome.

These dragons, glistening in shades of black, blue, brown, green, red, and yellow, are some of the most colorful creatures on the planet, with intricate patterns of stripes and spots. To Brown and Briggs, they are also some of the most elegant insects on Earth.

These aerial assassins have been around for about 300 million years. They survived the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. They have, so far, survived humankind’s destructive nature.

They can be found buzzing around in the swampy wilds of Rhode Island. In the summer, these winged acrobats perform stunts above and around ponds, lakes, streams, bogs, marshes, and rivers.

On a recent Saturday morning at the Great Swamp Management Area off Great Neck Road here,where the two conservationists guide public “hunts,” the longtime Rhode Island residents took this ecoRI News reporter on a 2-hour adventure in search of dragonflies and damselflies. See Brown’s book about these creatures.

My guides noted their favorite insects demonstrate charismatic behavior, possess an ancient evolutionary history, and play an important role in the ecology of aquatic habitats.

Virginia Brown, whose hat aptly captures her fondness for dragonflies and damselflies, has a keen eye for finding her favorite insects. To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Frank Carini is senior reporter and co-founder of ecoRI News

Damselfly

Pre-nap snack

“Even, Bird’s Milk’’ (oil), by John Asimacopoulos, at the Guild of Boston Artists

John Asimacopoulos’s bio at the Academy of Realist Art, Boston, reads:

That he “started as a student at the Academy of Realist art in September 2015, after making the decision to switch from a medical career to pursue an artistic one. His studies did not go to waste though, as they gave him knowledge, and appreciation of the human body, especially through his study of clinical anatomy, which included dissection. John applied what he learned, and started teaching artistic anatomy, and figure drawing in 2018. He has won numerous awards, including two Art Renewal Center scholarships in 2017, and 2018, the John F. and Anna Lee Stacey Scholarship Fund, as well as the Head Start Student Competition in 2017. He is currently working on the still life, and figure painting part of the program.’’

Despite the golden weather

Asters, those late summer beauties in New England

It seems so strange that I who made no vows

Should sit here desolate this golden weather

And wistfully remember—

A sigh of deepest yearning,

A glowing look and words that knew no bounds,

A swift response, an instant glad surrender

To kisses wild and burning!

Ay me!

Again it is September!

It seems so strange that I who kept those vows

Should sit here lone, and spent, and mutely praying

That I may not remember!

— “Again It Is September!,” by Jessie Redmond Fauset (1882-1961)

Llewellyn King: Is Biden perilously trying to hide his age?

“Old Age’’, by Robert Smirke (1752-1845), British painter

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Is Joe Biden hiding in plain sight?

Is his most extensive public effort these days fending off signs of age, hiding his infirmities, and clinging to the hope that he can still win in the election just over a year from now?

Sotto voce, the savants of the Democratic Party worry and complain in private that Biden is too old and infirm and should move over before it is too late. In public, they point to the health of the economy, receding inflation and the high employment rate, and foreign-policy wins.

But indeed, the Joe Biden of today isn’t the Joe Biden of yesterday.

The Biden we in the corps knew over the years in Washington was accessible, friendly, keen to please — and he talked. How he talked. Biden would give a speech, but he didn’t stop. He seemed to tack a second speech onto the first.

Biden didn’t change the course of history with his eloquence, nor set the audience to thinking in ways they hadn’t previously, but he was easy to take.

Now, he seems to approach the podium with caution, reading the speech with a just-get-me-through-this stoicism. The man who used to love the microphone appears to fear it.

Likewise, the man who used to enjoy the cut and thrust of interacting with the press eschews press conferences. He doesn’t hold them.

This absence of press conferences isn’t unimportant. They are messy and unruly, but they are where the acuity of the leader is tested and on display. They are where we might get a look at how he might be in negotiation with foreign leaders.

Press conferences are part of the democratic process, where the president reports to the public through the press. Like question time in the British House of Commons, they are where we see the president in action.

Boastful press releases — which every administration puts out — are no substitute. The nation deserves to see the president in action. Everything else is curated image-building by the White House staff.

A few questions tacked on ritually to the end of joint appearances with foreign heads of state aren’t a substitute. They are Potemkin affairs.

Republicans would love to bear down more on Biden’s age, but dare not. Their frontrunner, Donald Trump, is 77 — only three years younger than Biden; and, at 81, the Republican leader in the Senate, Mitch McConnell, is showing signs of health challenges linked to age.

Trump’s age is less discussed because his epic legal problems distract from whether he also might be too old.

The sad end of Winston Churchill’s political career should be a warning for all who cling to office too long.

The Conservative Party under Churchill lost the election immediately after World War II but was returned to office in 1951, and Churchill became prime minister for the second time. He was about to turn 77. Health warnings were ignored by his party and by his family.

The infirmities of age got in the way. Churchill was often confused, and new issues baffled him, said his friend the publisher Lord Beaverbrook.

According to historian Roger Scruton, during Churchill’s second administration, the seeds of what would haunt Britain later were sown: He failed to arrest the open border flow of immigrants from the former empire or to check the growth of trade-union power.

When Churchill, retired in 1955, his longtime deputy, Anthony Eden, took over and led the disastrous attempt to seize the Suez Canal in 1956.

Biden’s uncertain future is exacerbated by the seeming shortcomings of Vice President Kamala Harris. Despite attempts to bolster her, such as referring in press releases to the Biden-Harris administration, she is reportedly inept.

She is known to have had difficulty with her staff. In public, she appears frivolous, laughing inappropriately and showing little grasp of issues. She has left no mark on significant assignments handed to her by Biden, including immigration, voting rights and the influence of artificial intelligence.

No wonder a late-August poll from The Wall Street Journal showed 60 percent of eligible voters think that Biden isn’t “mentally up for the job of president.” In a CNN poll, 73 percent of Americans say they are seriously concerned that Biden’s age might negatively affect his current physical- and mental-competence level.

Churchill’s sad political decline shows even great men grow old. Biden can be seen on television going here and there: a blur of travel. But is this a man in hiding from a truth — his age?

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Downeast joys

Above, Treasures and Trash Barn in Sedgwick, Maine

Below, now closed lobster shack on Isle au Haut, an eatery once famous for its prize-winning lobster rolls.

— (The new!) photos by William Morgan

1908-1909 photos

Like this summer!

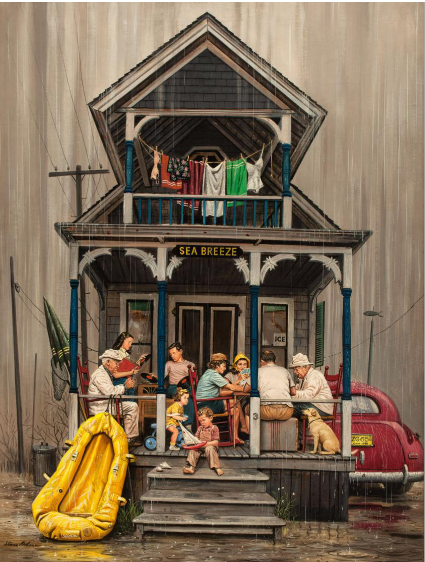

“Rained in Vacationers, Saturday Evening Post, 1948’’ (oil on canvas), by Stevan Dohanos, in the show “From the Masterworks of the Sanford B.D. Low Illustration Collection,’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art through Dec. 31. Mr. Dohanos lived much of his adult life in Westport, Conn.

The museum says the exhibition “showcases some of the collection’s finest examples and features iconic and groundbreaking artists, such as Maxfield Parrish (1870–1966), Norman Rockwell (1894–1978), Stevan Dohanos (1907–1994), and many others. These artists captured distinctly American values through story and advertisement illustrations, as well as through cover illustrations for publications such as Scribner’s Magazine and The Saturday Evening Post. Among the themes addressed in these captivating works are American pastimes, family and friends, love and romance, war time, as well as fantasy and science fiction.’’

Tom Conway: OT rules put lives at risk and strain families

The paper mill town of Madawaska, Maine

—Photo by P199

Via OtherWords.org

She only wanted a few hours at her dying mother’s bedside. But her bosses at Twin Rivers Paper, in Madawaska, Maine, forced her to work overtime on her day off. About an hour and a half into the mandatory shift, the woman’s mother died.

Workers are battling harder than ever to end this appalling mistreatment. They’re fighting back against mandatory overtime requirements that strain families to the breaking point and put lives at risk.

“It’s definitely caused a lot of heartache,” said David Hebert, financial officer and former president of United Steelworkers (USW) Local 291, one of three USW locals collectively representing about 360 workers at Twin Rivers.

USW members have long warned paper companies about the need to increase hiring and training to keep facilities operating safely. Yet some employers prefer to work people to the bone. Workers at Twin Rivers work a base shift of 12 hours — and each can be drafted for an additional 12-hour shift every month.

Even worse, a 12-hour shift can be extended with six hours of mandatory overtime without warning. Workers are often forced to pull multiple 18-hour days a week, especially when winter cold and flu season exacerbates the company’s intentional understaffing.

“People really hold their breath at the end of their shift,” explained Hebert. The coworker who lost her mother, for example, learned at the end of an 18-hour shift that she’d have to report the following day for overtime.

Other workers experience their own heartaches when unpredictable schedules leave them unable to make plans with their families or force them to miss graduations, anniversaries, birthday parties, or holiday gatherings.

“Family is the only reason we go into these places. I want to spend time with them, too,” said Justin Shaw, president of USW Local 9, which represents workers at Sappi’s Somerset Mill, in Skowhegan, Maine.

“You’ve got many people who work seven days a week,” with some required to log 24 hours at a stretch, Shaw said. “If we had better staffing levels, we wouldn’t have people working outrageous hours.”

Besides the toll it takes on family life, excessive overtime compounds risk in an industry that exposes workers to hazardous chemicals, fast-moving machinery, super-hot liquids and huge rolls of paper.

“It only takes a split second to lose a finger, an arm, or a life,” Shaw said, warning that extreme fatigue also puts workers at risk while commuting. “I’ve had many drives home that I can’t recall over half the ride. We have had many individuals in the ditch or wreck vehicles trying to keep up with the demands.”

A bill in Maine would limit mandatory overtime to no more than two hours a day and require employers to provide a week’s notice before mandating extra hours or changing a worker’s schedule.

The legislation places no caps on voluntary overtime, nor would it apply to true emergencies when a mill needs extra hands to avert “immediate danger to life or property.” But it would end the capricious usurping of workers’ lives that now occurs because the industry refuses to hire enough people.

Union members also continue to drive change at the bargaining table. Some workers are pushing to create “share pools” of workers whose role is to fill in where needed on a given shift.

“Share pools” virtually eliminated mandatory overtime at the Huhtamaki facility in Waterville, Maine, where workers once had to put in so many hours that some slept in their cars rather than commute home, said Lee Drouin, president of USW Local 449.

Drouin said other paper companies also need to realize that change is essential for workers but benefits them as well. “The mills have to understand, this is not going to go away,” he said. “To me, it makes a lot more sense to have happy workers and safe workers.”

Tom Conway is the international president of the United Steelworkers Union (USW). This article was produced by the Independent Media Institute and adapted for syndication by OtherWords.org.