Pay ‘em to clear out?

Aerial view of Holland-low Barrington, R.I., in 2008

— Photo by Brian McGuirk

How Much to Pay Them?

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

As the sea level rises, and coastal storms seem to be becoming more severe, more and more states and localities are realizing that in many stretches of low-lying coast, the only long-term solution is to remove houses and other structures, in what has been called “managed retreat.’’ The tricky thing is how to pay for it, especially since shoreline houses tend to be expensive.

Should homeowners who, after all, presumably know (or should know) the risks of owning waterfront property be compensated with tax money for being forced to leave their houses to be demolished or to pay them to move their houses?

Get ready for buyouts, relocating roads and changing zoning ordinances and districts. This could be particularly exciting in towns, such as Warren and Barrington, R.I., where so much of the land is barely above sea level.

A lot of shoreline homeowners, who include a disproportionate number of politically powerful rich people, will be, er, inconvenienced. And towns and cities will worry about the loss of property-tax revenue.

Localities, led by new state policies, should start planning where, or if, buildings and public infrastructure can be relocated, and meanwhile promote marshland expansion, which will help mitigate flooding in stores.

This should be done with all deliberate speed. Global warming is speeding up.

‘What are we?’

“Afflicta,’’ by Rockland, Maine-based photographer Chelsea Ellis, at the Maine Museum of Photographic Arts, Portland, through Sept. 30.

Ms. Ellis says:

“In my photographic work, I use my body and paint to create composite portraits of humanoid forms that blur the boundaries between the familiar and unfamiliar, investigating structures of the human body and posing the questions: Who are we? What are we?’’

Rockland location.

— Graphic by Rcsprinter123

Mapping urban spaces for the public interest

Jonas Clark Hall, the main academic facility for undergraduate students

Edited from a New England Council report

“Clark University, in Worcester, has announced that it will become the first academic institution and founding member of PLACE, a nonprofit data trust committed to mapping urban spaces for the public interest.

“Founded in 2020, PLACE is a technology organization committed to solving the inefficiencies of current urban geo-information data by bridging the gap between and providing data to public and private members. Clark’s Graduate School of Geography (GSG) will support the initiative by using remote sensing to collect high-resolution imagery, which will be open for government and member use. Once surveyed, data from these regions can support research and legislation in a variety of subject areas ranging from housing information to food security.

“‘Clark’s partnership with PLACE will offer our researchers new opportunities to study the processes underlying global change, particularly urbanization, improving our ability to identify solutions to some of our most pressing challenges,’ said Lyndon Estes, associate professor in the GSG.’’

The menace of moving

1912 postcard

“In the kind of New England I’m from, you are expected to stay and marry someone from New England – well, Maine, actually – so I think it was seen as a betrayal when I left for New England, which has been my refuge.’’

--Elizabeth Strout (born 1956 in Portland, Maine) is a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist. She is married to former Maine Atty. Gen. James Tierney and divides her time between New York City and Brunswick, Maine.

David Warsh: 'Suzerainties in economics are personal'

The Great Dome at the Massachusetss Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Mass.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

When I was a young journalist, just starting out, the economist whose writings introduced me to the field was Gunnar Myrdal. He hadn’t yet been recognized with a Nobel Prize, as a socialist harnessed to an individualist, Friedrich Hayek. That happened in in 1974. But he had written An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944) , about the policy of segregation that had been restored de jure after the U.S. Civil War. A subsequent project, Asian Drama: An Inquiry into the Poverty of Nations (1968), longer in preparation, was in the news.

Myrdal’s pessimistic assessment of the prospects for economic growth in India, Vietnam, and China began to fade soon after it appeared. The between-the-wars era of economics in which he was prominent already had been superseded by a new era, dominated by Paul Samuelson, whose introductory college textbook Economics (1948), supplemented by the highly technical Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947), quickly replaced overnight Alfred Marshall’s Principles of Economics, whose first edition had appeared in 1890.

Basic textbooks dominate their fields by dint of the housekeeping that they establish. Samuelson has ruled economics ever since through the language he promulgated; mathematical reasoning was widely adopted within a few years by newcomers to the profession. Ruling textbooks are sovereign. Since the discovery and identification of the market system two hundred and fifty years ago, there have been only five such sovereign versions: Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, Alfred Marshall, and Samuelson (brought up to knowledge’s frontiers thirty years ago by Andreu Mas-Colell).

Sovereignty is binary; it either exists or doesn’t. A suzerainty, on the other hand, though part of the main, sets its own agenda. John Fairbank taught that Tibet was a suzerainty of China. (This Old French word signifies a medieval concept, adopted here to describe modern sciences, as in Dani Rodrik’s One Economics, Many Recipes (2007).

Suzerainties are personal. They rule through personal example. Replacing Myrdal as suzerain in my mind, in 1974, practically overnight, was Robert Solow. Eight years his junior, Solow was Samuelson’s research partner at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for the next thirty years. Samuelson retired in 1982, died in 2009. Solow soldiered on.

Solow turned 99 last week, hard of hearing but sharp as ever otherwise (listen to this revealing interview if you doubt it.) By now his suzerainty has passed to Professor Sir Angus Deaton, 78, of Princeton University.

What is required to become a suzerain? Presidency of the American Economic Association and a Nobel Prize are probably the basic requirements: recognition by two distinct communities, one for good citizenship within the profession, the other for scientific achievement beyond it, to the benefit to all humanity.

In Deaton’s case, as in Myrdal’s, it helps to have displayed a touch of Alexis de Tocqueville, whose two-volume classic of 1835 and 1840, Democracy in America, set the standard for critical criticism by a visitor from another culture, and, in the process, founded the systematic study today we call political science. Deaton grew up in Scotland, earned his degrees at Cambridge University, and was professor of economics at the University of Bristol for eight years, before moving to Princeton. in 1983. For the first twenty years he taught and worked in relative obscurity on intricate econometric issues. In 1997, he began writing regular letters for the Royal Economic Society Newsletter, reflecting on what he had learned recently about American life, “sometimes in awe, and sometimes in shock”.

In 2015, the year Deaton was recognized by the Nobel Foundation for “his analysis of consumption, poverty, and welfare,” he published The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality. Five years later, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism appeared, by Deaton and Anne Case, his fellow Princeton professor and economist wife, just as the Covid epidemic began. It became a national best-seller, focusing attention on the fact that life expectancy in the United States had recently fallen for three years in a row – “a reversal not seen since 1918 or in any other wealthy nation in modern times.”

Hundreds of thousands of Americans had already died in the opioid crisis, they wrote, tying those losses, and more to come, to “the weakening position of labor, the growing power of corporations, and, above all, to a rapacious health-care sector that redistributes working-class wages into the pockets of the wealthy.”

Now Deaton has written a coda to all that. Economics in America: An Immigrant Economist Explores the Land of Inequality (Princeton 2023) will appear in October, offering a backstage tour during the year that Deaton has been near or at the pinnacle of it. I spent most of Friday and Saturday morning reading it, more than I ordinarily allot to a book, and found myself absorbed in its stories about particular people and controversies, on the one hand, and, on the other, increasingly apprehensive about finding something pointed about it to say.

Then it occurred to me. I have long been a fan of Ernst Berndt’s introductory text, The Practice of Econometrics: Classic and Contemporary (Addison-Wesley, 1991), mainly because it scattered one- or two-page profiles of leading econometricians throughout pages of explication of their ideas and tools. Deaton’s new book is far better than that, because no equations are to be found in the book, and part of some of those letters to British economists have been carefully worked in.

The argument about David Card and the late Alan Krueger’s celebrated paper pater about a natural experiment with the minimum wage along two sides of the Delaware River, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, is carefully rehashed (both were Deaton’s students). The goings-on at Social Security Day at the Summer Institute of the National Bureau of Economic Research is described. The “big push” debate in development economics among William Easterly, Jeffrey Sachs, Treasury Secretary Paul H O’Neill, and Joseph Stiglitz get a good going-over. Econometrician Steve Pischke’s three disparaging reviews of Freakonomics are mentioned. Rober Barro and Edward Prescott are raked over with dry Scottish wit; Edmond Malinvaud, Esra Bennathan, Hans Binswanger-Mkhizer, and John DiNardo are celebrated. The starting salaried of the most sought-after among each year’s newly-minted economics PhDs are discussed:

My taste is for theory because developments in theory are where news is apt to be found. That’s why I liked Great Escape and Deaths of Despair so much. Economics in America is undoubtedly the best book about applied economics I’ve ever read, its breadth and depth. But it is a book about applied economics – the meat and potatoes topics that I have tended to avoid over the years. What I craved when I finished is a book about the one-time land of equality that is Britain today.

Other suzerainties exist in economics. The same and/or credentials apply: presidency of the AEA and realistic hopes of a possible Nobel Prize. They tend to be associated with particular universities: Robert Wilson, Guido Imbens, Susan Athey, Paul Milgrom and Alvin Roth at Stanford; George Akerlof (emeritus), David Card and Daniel McFadden at Berkeley; Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz at Harvard; William Nordhaus and Robert Shiller at Yale; James Heckman and Richard Thaler at Chicago; Daron Acemoglu and Peter Diamond at MIT; Sir Angus Deaton, Christopher Sims, and Avinash Dixit at Princeton.

Alas, the reigning head of the suzerainty in which I am most interested, macroeconomist Robert Lucas, died earlier this year, and won’t soon be replaced. He succeeded Sherwin Rosen, his best friend in the business, in the AEA presidency in 2001. Rosen died the same year, a decade or two short of what might have been his own trip to Stockholm.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Going, going, gone

“The Melting of the Lewis Glacier on Mt. Kenya,’’ photo by Simon Norfolk, in the group show "Ceding Ground,’’ at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Winchester, Mass.

The museum says:

“‘Ceding Ground’ is a view of our changing climate through the eyes of six photographers, all dealing with the question of loss of habitat, groundwater and climate change. Simon Norfolk’s two series, ‘When I am laid in Earth’ and ‘Shroud,’ focus on retreating ice in Africa and Europe. Jason Lindsey’s ‘Cracks in the Ice’ is a metaphorical and scientific look at glaciation. Camille Seaman’s ‘Melting Away’ exposes us to habitat loss for the penguins of Antartica. ‘Hidden Waters’ is Bremner Benedict’s look at the water crisis in the western United States. Ellen Konar and Steve Goldband expose us to climate change through the study of tree rings in ‘Cut Short’. Outside the museum we have Dawn Watson’s 'Alchemy, ‘ an abstract look at the elements that surround us and Ville Kansanen’s site-specific installations connecting the museum to the surroundings, engaging Judkin’s Pond as a partner in his vision to talk about the fragility of aquatic resources.”

The Aberjona River just below the mill pond in Winchester center

And they’re in charge

“Flags of Our Mothers,’’ by Raven Halfmoon, at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, in Ridgefield, Conn.

Raven Halfmoon (Caddo Nation) is from Norman, Okla.

Old Labor Day parades and a video

The Brotherhood of Boiler Makers Lodge 245 on Labor Day, 1915, in front of the Wonalancet Club, in Concord {N.H.}, just after marching in the Concord Labor Day Parade.

— Photo at the Concord Public Library

‘Into the dark decayed’

The same leaves over and over again!

They fall from giving shade above

To make one texture of faded brown

And fit the earth like a leather glove.

Before the leaves can mount again

To fill the trees with another shade,

They must go down past things coming up.

They must go down into the dark decayed.

They must be pierced by flowers and put

Beneath the feet of dancing flowers.

However it is in some other world

I know that this is way in ours.

“In Hardwood Groves,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Martha Bebinger: In Mass. and beyond, health-care workers confront the rising dangers from a warming climate

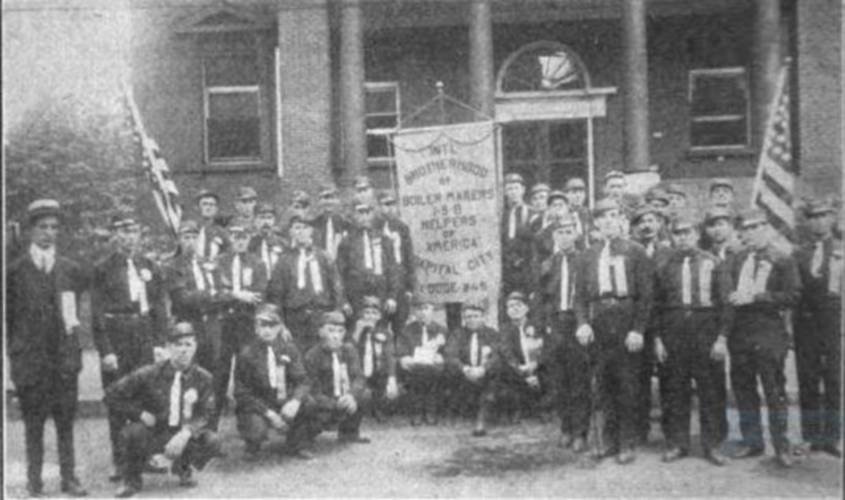

The National Weather Service risk categories for heat

Boston and some adjoining communities

Text via KFF Health News in partnership with WBUR and NPR

BOSTON

An important email appeared in the inboxes of a small group of health-care workers north of this city as this summer started. It warned that local temperatures were rising into the 80s.

An 80-plus-degree day is not sizzling by Phoenix standards. Even in Boston, it wasn’t high enough to trigger an official heat warning for the wider public.

But research has shown that those temperatures, coming so early in June, would likely drive up the number of heat-related hospital visits and deaths across Greater Boston.

The targeted email alert the doctors and nurses at Cambridge Health Alliance, in Somerville, Mass,, got that day is part of a pilot project run by the nonprofit Climate Central and Harvard University’s Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment, known as C-CHANGE.

Medical clinicians based at 12 community-based clinics in seven states — California, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wisconsin — are receiving these alerts.

At each location, the first email alert of the season was triggered when local temperatures reached the 90th percentile for that community. In a suburb of Portland, Ore., that happened on May 14 during a springtime heat wave. In Houston, that occurred in early June.

A second email alert went out when forecasts indicated the thermometer would reach the 95th percentile. For Cambridge Health Alliance primary- care physician Rebecca Rogers, that second alert arrived on July 6, when the high hit 87 degrees.

The emails remind Rogers and other clinicians to focus on patients who are particularly vulnerable to heat. That includes outdoor workers, older adults, or patients with heart disease, diabetes, or kidney disease.

Other at-risk groups include youth athletes and people who can’t afford air conditioning, and/or who don’t have stable housing. Heat has been linked to complications during a pregnancy as well.

“Heat can be dangerous to all of us,” said Caleb Dresser, director of health- care solutions at C-CHANGE. “But the impacts are incredibly uneven based on who you are, where you live, and what type of resources you have.”

The pilot program aims to remind clinicians to start talking to patients about how to protect themselves on dangerously hot days, which are happening more frequently because of climate change. Heat is already the leading cause of death in the U.S. from weather-related hazards, Dresser said. Letting clinicians know when temperatures pose a particular threat to their patients could save lives.

“What we’re trying to say is, ‘You really need to go into heat mode now,'” said Andrew Pershing, vice president for science at Climate Central, with a recognition that “it’s going to be more dangerous for folks in your community who are more stressed.”

“This is not your grandmother’s heat,” said Ashley Ward, who directs the Heat Policy Innovation Hub, at Duke University. “The heat regime that we are seeing now is not what we experienced 10 or 20 years ago. So we have to accept that our environment has changed. This might very well be the coolest summer for the rest of our lives.”

The alerts bumped heat to the forefront of Rogers’s conversations with patients. She made time to ask each person whether they can cool off at home and at work.

That’s how she learned that one of her patients, Luciano Gomes, works in construction.

“If you were getting too hot at work and maybe starting to feel sick, do you know some things to look out for?” Rogers asked Gomes.

“No,” said Gomes slowly, shaking his head.

Rogers told Gomes about early signs of heat exhaustion: dizziness, weakness, or profuse sweating. She handed Gomes tip sheets she’d printed out after receiving them along with the email alerts.

They included information about how to avoid heat exhaustion and dehydration, as well as specific guidance for patients with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dementia, diabetes, multiple sclerosis and mental-health concerns.

Rogers pointed out a color chart that ranges from pale yellow to dark gold. It’s a sort of hydration barometer, based on the color of one’s urine.

“So if your pee is dark like this during the day when you’re at work,” she told Gomes, “it probably means you need to drink more water.”

Gomes nodded. “This is more than you were expecting to talk about when you came to the doctor today, I think,” she said with a laugh.

During this visit, an interpreter translated the visit and information into Portuguese for Gomes, who is from Brazil and quite familiar with heat. But he now had questions for Rogers about the best ways to stay hydrated.

“Because here I’ve been addicted to soda,” Gomes told Rogers through the interpreter. “I’m trying to watch out for that and change to sparkling water. But I don’t have much knowledge on how much I can take of it.”

“As long as it doesn’t have sugar, it’s totally good,” Rogers said.

Now Rogers creates heat-mitigation plans with each of her high-risk patients. But she still has medical questions that the research doesn’t yet address. For example: If patients take medications that make them urinate more often, could that lead to dehydration when it’s hot? Should she reduce their doses during the warmest weeks or months? And, if so, by how much? Research has yielded no firm answers to those questions.

Deidre Alessio, a nurse practitioner at Cambridge Health Alliance, also has received the email alerts. She has patients who sleep on the streets or in tents and search for places to cool off during the day.

“Getting these alerts makes me realize that I need to do more homework on the cities and towns where my patients live,” she said, “and help them find transportation to a cooling center.”

Most clinics and hospitals don’t have heat alerts built into electronic medical records, don’t filter patients based on heat vulnerability, and don’t have systems in place to send heat warnings to some or all of their patients.

“I would love to see health care institutions get the resources to staff the appropriate outreach,” said Gaurab Basu, a Cambridge Health Alliance physician who co-directs the Center for Health Equity Advocacy and Education at Cambridge Health Alliance. “But hospital systems are still really strained by COVID and staffing issues.”

This pilot program is an excellent start and could benefit by including pharmacists, said Kristie Ebi, founding director of the Center for Health and the Global Environment, at the University of Washington.

Ebi has studied heat early-warning systems for 25 years. She says one problem is that too many people don’t take heat warnings seriously. In a survey of Americans who experienced heat waves in four cities, only about half of residents took precautions to avoid harm to their health.

“We need more behavioral-health research,” she said, “to really understand how to motivate people who don’t perceive themselves to be at risk, to take action.”

For Ebi and other researchers, the call to action is not just to protect individual health, but to address the root cause of rising temperatures: climate change.

“We’ll be dealing with increased exposure to heat for the rest of our lives,” said Dresser. “To address the factors that put people at risk during heat waves, we have to move away from fossil fuels so that climate change doesn’t get as bad as it could.”

Martha Bebinger is a reporter at WBUR, in Boston

marthab@wbur.org, @mbebinger

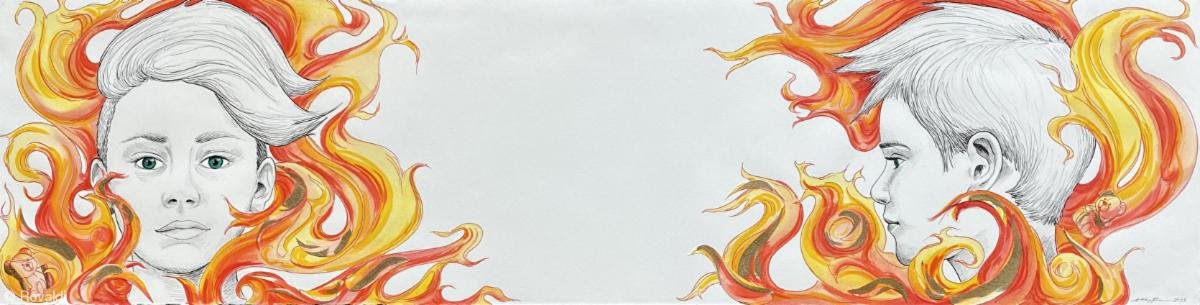

And they don't bite

“Hello, Bessie. Hello, Roland.” (mixed media), by Abby Rovaldi, in the group show “Creature Comforts,’’ at the Attleboro (Mass.) Arts Museum, through Sept. 23. Her studio is in Franklin, Mass.

— Photo courtesy of Ms. Rovaldi

The museum says that the show asks 17 artists to interpret themes from the novel Nothing to See Here, by Kevin Wilson, with 2D and 3D representations of stuffed animals. It provides artists the opportunity to "bring their favorite stuffed companions back to life," complete with "biographies" for each animal.

Sleepy downtown Franklin, Mass.

Llewellyn King: Wherein we go cruising for out-of-control tourism

Costa Mediterranea in Argostoli, Greece

— Photo by Kefalonia2015

Huge cruise ship at Bar Harbor, Maine. Cruise ships are increasingly irritating many locals in famous tourist spots in New England in the cruise lines’ May-October season.

Europe reeled this summer from heat, wildfires, migrants and worries about Russia’s war in Ukraine, but also from too much tourism. I know, I was part of the problem.

Tourism is the quick economic fix for poor nations, but it is also important to rich ones — until both get too much of it.

The places everyone wants to visit, often places on bucket lists, are choking on their success. Paris, Britain’s Stonehenge and the Lake District, Ireland’s Ring of Kerry and the jewels of Italy, Florence and Venice, all suffer summer overload.

Things were so bad in Venice this summer that cruise ships had to be waived off. The Greek islands of Santorini, Corfu and Mykonos were, likewise, inundated with cruisers and other tourists.

Yet tourism is vital to many economies. The emerging tourist destinations along Croatia’s Dalmatian Coast are the latest to feel the benefits and problems of tourism. The sites, the roads and the facilities are stretched, but tourism has meant economic well-being for the region, especially as cruise ships have started calling.

Cruise ships, those big – and becoming gigantic — floating palaces overwhelm ports when they anchor, burden infrastructure and deposit lots of lovely money.

Greece and many countries along the Adriatic Sea derive about 25 percent of their GDP from tourism, not the least of it from cruise ships. Cruise ships are very important to any shore community that has ancient ruins, historical and scenic cities, natural wonders — and the Balkan countries have all in abundance.

In early August, my wife and I cruised the Dalmatian Coast and Greek islands. When we booked the cruise, at the last minute, we were fully aware of the tourist pressure on Europe every summer, but learned that it is getting worse.

Most of the Dalmatian Coast is still visitable in summer and hugely rewarding, except for Dubrovnik, which we skipped. It is, I learned, showing stress from over-tourism. The full impact of the cruise ships hasn’t yet begun to wear on the small coastal towns, as it has on the most famous Greek islands.

You can’t pick a Greek islands itinerary in the summer that will avoid seeing too many cruise ships, carrying 2,500 and up passengers, arriving at the same destination at the same time.

Fira, on Santorini, is a fabulous cliff town, except when there are too many visitors going ashore from a flotilla of cruise ships anchored in the harbor.

Five cruise ships arrived at Fira simultaneously, ours among them, and untold thousands of tourists went ashore. To reach the charming town, you must ride a donkey or a cable car. My wife and I love donkeys, so we opted for the cable car. It was chaotic, verging on dangerous. Extraordinarily, the crowds waiting for hours to board the cable cars were well-behaved: no pushing, no audible outrage, just resigned queuing.

Lest you think cruise ships are filled only with Americans, cruising has become a global passion.

Cruisers see the world from the comfort and security of a very large, well-organized hotel that moves with them. They see so much more and take their selfies in so many more places than they could otherwise.

Cruising is big business, and the size of the ship seems not to deter anyone.

Royal Caribbean is about to add its Icon class: They will carry up to 7,000 passengers and 3,000 crew. To merchants and tax collectors they are golden galleons as the visitors spend their doubloons on tours, trinkets, meals and tips.

But over-tourism degrades the picturesque ports, cherished villages, and great structures of the past.

When I see a cruise ship, towering over a town from where history was born, I think: The barbarians arrive in shorts, clutching cameras and cell phones. I may be one of them, but I shall endeavor to avoid high summer in the future.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

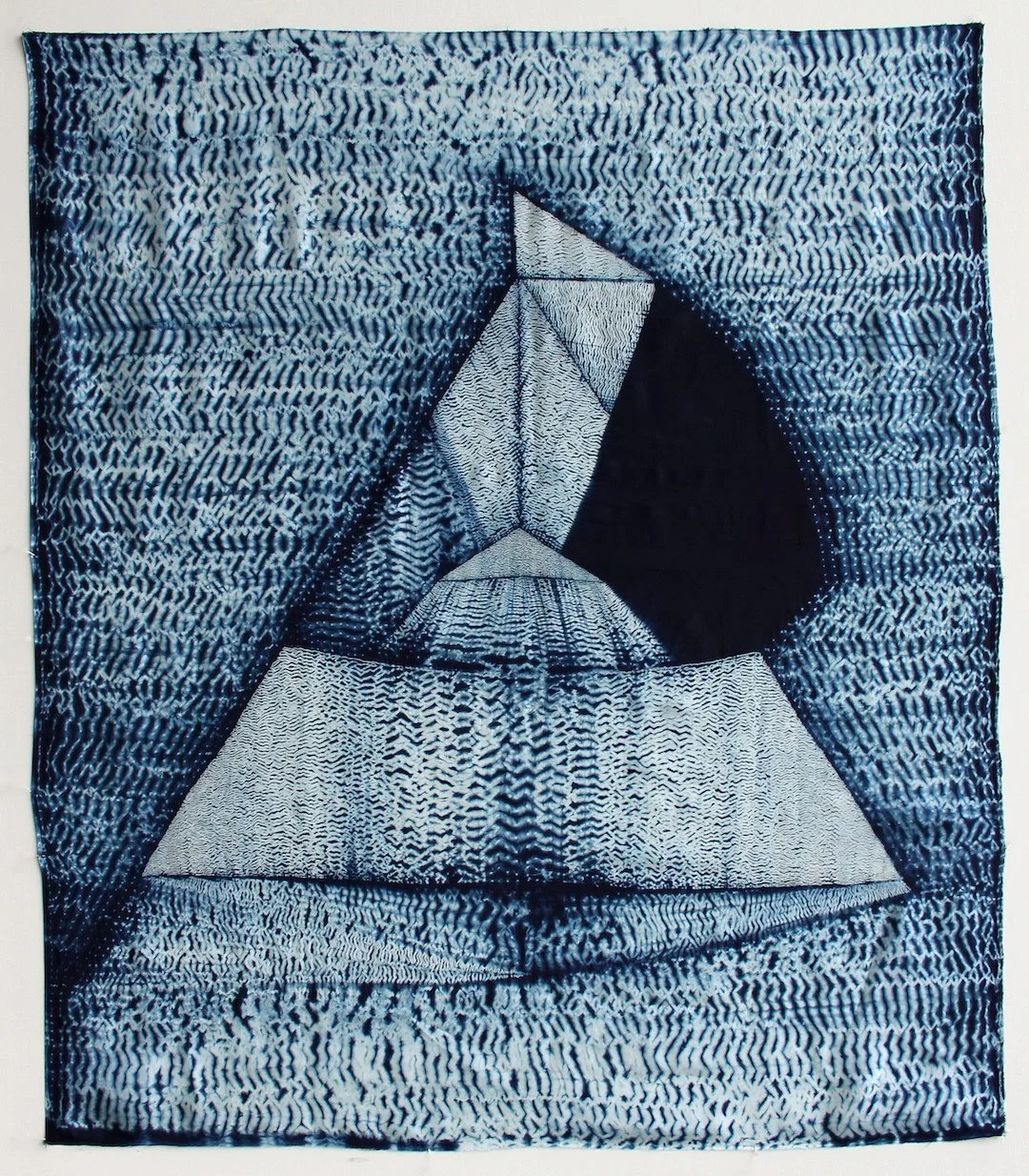

Intriguing indigo

Work by Davana Robedee in her show “As Above, So Below,’’ at 3S Artspace, Portsmouth, N.H., Sept. 8-Nov. 12

She says:

“Indigo dye is an intriguing substance. It strikes a balance between precise science and magical experience. Long before its scientific understanding, indigo was used all over the world for its color, but it was also revered for its magical transformation from green to blue in the dye process. Before knowing that on the molecular level, indigo was bonding with oxygen, it was described as ‘breathing’ as if it were a living entity. Through growing and dyeing with it, I find a place to hold both the spiritual and the scientific. Its place in my practice is symbolic and functional. The same is true for hand-stitched resist shibori as a method of making marks on fabric. It slows down my experience of time and the imagery references my parasomnia hallucinations. It gives rise to two narratives- that I slow down time and a create a magical transformation, or that I bind fabric and use a chemical reaction to create a pattern. Through this I question- are these arcane symbols from a world beyond consciousness, or simply a misfiring of the brain?’’

Portsmouth waterfront in 1917

Always headwinds

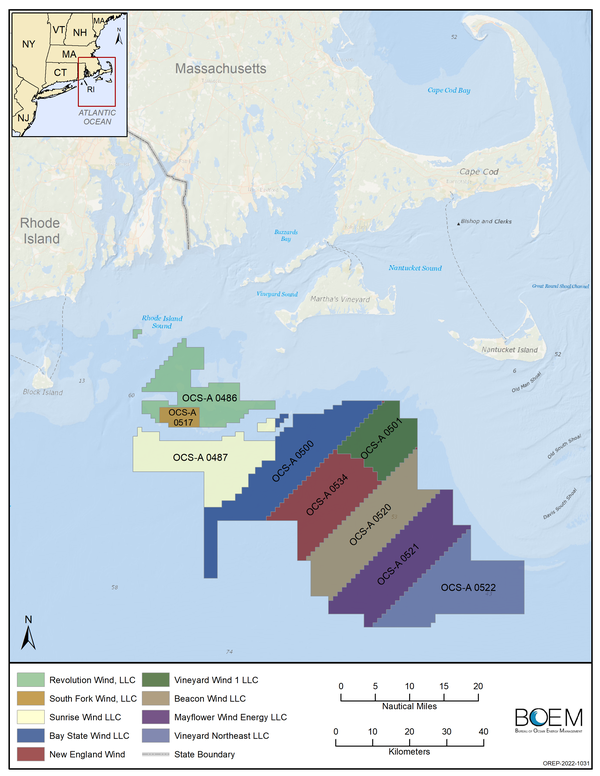

Wind-energy lease areas off Massachusetts and Rhode Island as of October, 2022

The Massachusetts Wind Technology Testing Center, in Boston’s Charlestown section.

— Photo by vArnoldReinhold

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It was good to hear that the U.S. Interior Department has approved Revolution Wind’s big (700 megawatts) project, southwest of Martha’s Vineyard. The project could provide electricity for 350,000 homes and create about 1,200 construction jobs.

The department has also approved the Vineyard Wind 1 project, off Massachusetts, the South Fork Wind project, off Rhode Island and New York, and the Ocean Wind 1 project, off New Jersey.

But the regulatory approval process moves at glacial speed, and litigation always threatens to stop such projects in their tracks. Big factors are nimbyism by coastal residents (often led by affluent summer people) who say that they don’t want to look at wind turbines, as well as opposition by some in the fishing sector because of the mostly temporary disruptions in the areas where they’d be installed. Of course, the damage caused by man-made global warming happens everywhere, in varying degrees of severity.

And the supports for offshore turbines act as artificial reefs that draw fish. Wouldn’t fishermen like that?

Installing any energy source creates problems, but let’s make rational comparisons….

The complaints by offshore-wind foes are outstandingly hypocritical. Consider that the fossil-fuel burning that wind power is meant to partly replace poses an existential risk to fishing interests by dangerously warming and acidifying the water and disrupting major ocean currents such as the Gulf Stream. Fossil-fuel burning destroys food sources of marine animals, including whales.

Then there are those pesky oil spills and the disruptions to marine animals by speeding oil tankers.

When you look closely at opposition to coastal and offshore wind projects you see money from – you guessed it! – the oil and gas industry.

Take a look at the stuff in these links:

https://electrek.co/2022/04/18/the-first-us-offshore-wind-farm-has-had-no-negative-effect-on-fish-finds-groundbreaking-study/

https://grist.org/politics/republicans-fossil-fuels-the-gop-donors-behind-a-growing-misinformation-campaign-to-stop-offshore-wind/

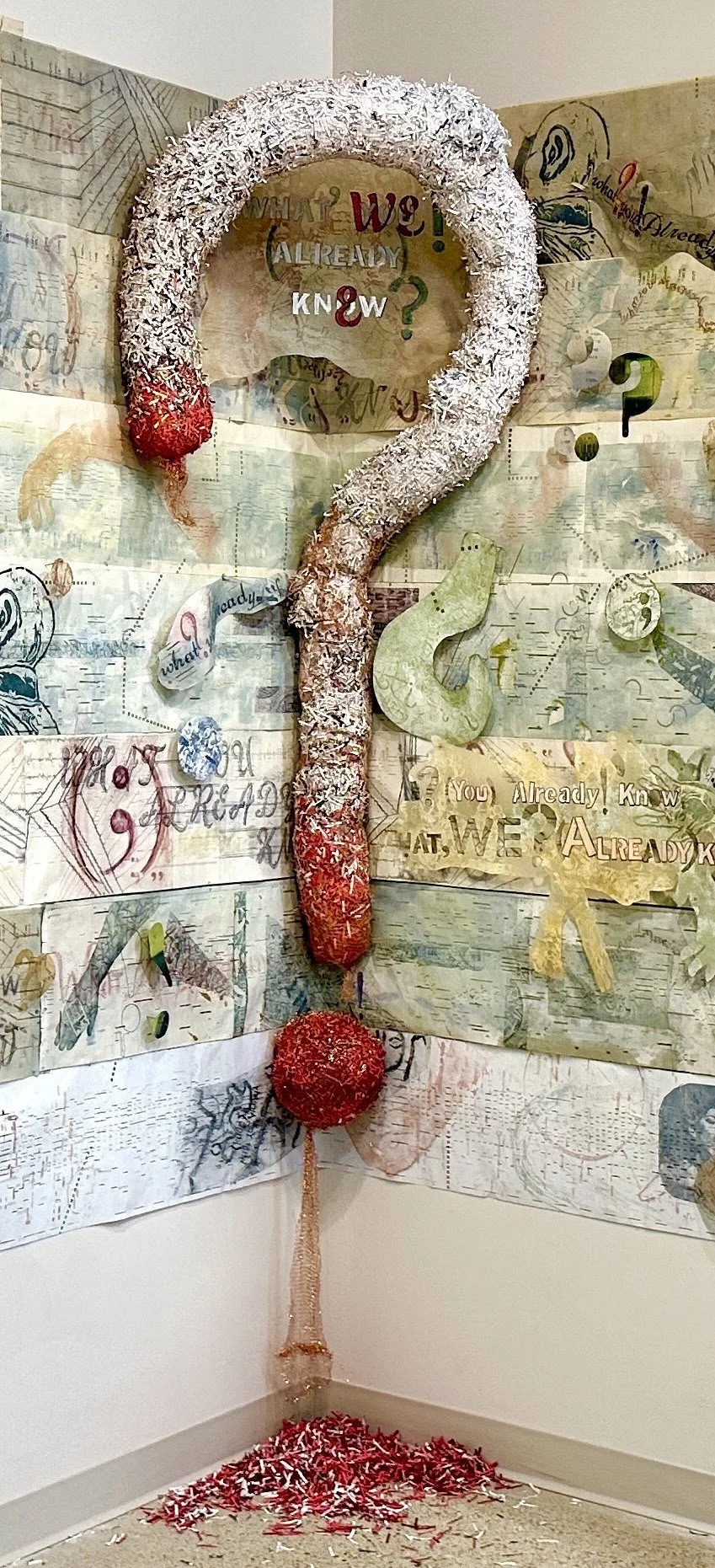

‘Visual equivalents’

“Scrip(t) Scraps, Version 1’’ (intaglio, relief prints on player piano scrolls with 5.5’ etched copper parentheses, copper mesh stuffed with shredded paper), by Somerville, Mass.-based artist Randy Garber, in her show “Scrip(t) Scraps,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Nov. 1-20.

She says:

‘“My work investigates perception and how meaning is deciphered. I have consistently—and persistently—focused on finding ways to visually express both the beauty and vagaries of communication. Profoundly hard of hearing since infancy and acutely aware of the potential for misinterpretation, I explore the spaces between silence and sound: confusion and clarity, chaos and precision.

“Interested in gaps between our five (known) senses and how they inform, influence and intercept one another, I aim to find visual equivalents that suggest the complicated processes in how we receive and make sense of information. I create structures and images that evoke, for instance, cochlea, ear drums, instruments, neural networks and language systems.’’

Chris Powell: Conn. cities can’t save themselves

Vanderbilt Hall at Yale

— Photo by GK tramrunner229

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Yale University's police union seems to have thought last week that it could scare up a better contract by distributing to incoming freshmen a handbill suggesting that New Haven is so dangerous that just leaving their rooms in the university cocoon could get them killed. Crime and violence in New Haven are "shockingly high," the handbill said.

Mayor Justin Elicker and other city officials denounced the union's fear mongering, accused the flyer of inaccuracies, and insisted that crime in the city has been coming down. (It depends on the duration measured.)

It waa hard to see how the flyer made a case for a better contract. But most places are far safer than New Haven.

After all, New Haven has a large impoverished population, has shootings almost every day -- some fatal -- and every month the state's prisons send back to the city dozens of troubled former offenders who soon will return to crime.

If New Haven was as safe as those offended by the flyer want people to believe, the city wouldn't have a "shot spotter" system to hasten police response to the constant mayhem, and Yale would not offer security escorts to students around the clock on campus.

But Yalies recognize the university's urban environment and probably have noticed the deteriorating conditions in many cities. Yale's reputation has induced them to take a risk.

So the controversy over the flyer is worthwhile mainly for the rest of Connecticut, whose social contract long has been to accept disintegration in the cities as long as it can be confined. Since increasingly it cannot be confined, maybe it will be addressed seriously only if it keeps spreading.

For try as they might, the cities aren't equipped to save themselves, being so poor and torn between crime victims and perpetrators, most of each group being city residents. Like every victim, every perpetrator is a disaster for his family.

At a recent meeting, Hartford's City Council noted that serious crime in the city is committed disproportionately by repeat offenders the courts have failed to put away for good or even to bring to any resolution at all, leaving many free on bond for long periods and committing more crimes.

Hartford's police say 73 percent of violent criminals in the city have been arrested before and 79 percent of perpetrators in shootings have already been arrested for other gun crimes. As of a few days ago Hartford had suffered 28 murders this year, a rate higher than last year's, and -- hardly noticed -- 67 people had survived shootings in the city.

This should be an outrage beyond Hartford, but it's not, and the city council has no jurisdiction over repeat offenders or crime generally. It can only appropriate for more police.

The Hartford-area chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People also has noted rising crime in the city. But its idea is only to alert city residents to the many "resources" available to them, like food pantries. That won't tame wild young men.

Running for mayor, Hartford state Sen. John Fonfara comes closest to the underlying problem.

In an interview this month Fonfara implicitly referred to what is usually unmentionable in Connecticut: child neglect at home engendered by the welfare system and social promotion in school. He cited children who "start school unready, or they couldn't read by third grade and get discouraged. They end up in ninth grade but they're at a sixth-grade or fifth-grade level, and they're too old and they quit. … Maybe they don't have support at home in their neighborhood. Maybe some of their friends are involved in a gang, and then it goes from there."

The remedy Fonfara offered was weak: more pre-school. But at least it was relevant, and it's probably too much to expect a candidate for mayor to ask directly where all this child neglect is coming from in a city that is full of it.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

‘Contemplation and curiosity’

Work by Japanese-American and Boston-based artist Yuko Oda, in her show “Entering, Arriving, Departing, at Boston Sculptors Gallery, Aug. 30-Oct. 1.

The gallery says:

“Yuko Oda’s personal history involves lifelong pilgrimages to her homeland of Japan. On a recent trip she visited several shrines and temples, walking through numerous gates and performing rituals such as ringing bells to pay respect and purifying oneself with water. Oda also recently experienced a loss in her family. These events coalesced into the creation of ‘Arriving, Entering, Departing,’ an immersive installation where visitors are invited to remove their shoes, enter, and experience a place of contemplation, curiosity, and wonder.’’

Black Mainer anti-racism hero

“I felt that fighting discrimination was the most important thing I could do as an elected official. I said then and I believe now that any doctrine of superiority is scientifically false, morally condemnable, socially unjust and dangerous.’

— Gerald E. Talbot (born 1931 and one of the few Mainers with an African-American background), civil-rights leader and former state representative from Portland.

An eighth-generation Mainer, Talbot traced his ancestry to black Revolutionary War veteran Abraham Talbett.

Talbot was the first Black state legislator in Maine, the founding president of the Portland chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and president of the Maine State Board of Education under Gov. Joseph Brennan. In 2020, the Riverton Elementary School, in Portland, was renamed the Gerald E. Talbot Community School.

Step into versions of the past

Photo by Eileen McCarney Muldoon, in her show “Memory or Imagination: The Work of Eileen McCarney Muldoon,’’ at the Jametown (R.I.) Arts Center, Nov. 9-Dec. 16

Ms. Muldoon, who lives in Jamestown, says of her work:

“I have always been fascinated with how our backstories influence our life. Our past world touches us directly and carves our future. Yet, our memories are blurred and tangled by our own perception and imagination. Even the most precise memory is translated through our own rendering. If I were to transcribe my memories through words, you would have foreclosure. You would be given a narrative, most likely fiction, but nonetheless you would be given my story. Instead, I have used my photographs of dreams, imagination and metaphor to suggest a past world that you too can step into and interpret. My hope is that you connect with these images without insistence and relate to these musings to shine a light into your past world before entering into the unknown journey ahead.’’

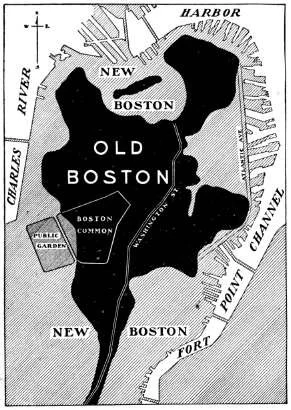

Swelling city

This shows the original dimension of the Shawmut Peninsula, on which Boston was first built, staring in 1630. The gray areas marked with the words "New Boston" are the product of the period of filling in mudflats that began in 1803.