Chris Powell: Only obnoxious students justify teacher raises now; justice system runs on sometimes dubious plea bargains

Young student wearing dunce hat as punishment in 1906 photo

Latch-key kid of parents who aren’t home

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Student performance continues to crash in schools in Connecticut and throughout the country. The results of the latest National Assessment of Educational Progress tests showed steep declines in the reading and math proficiency of 13-year-olds. Students are doing worse than a decade ago.

But as usual there is much clamor to increase compensation for teachers, to hire more teaching assistants, and to keep increasing spending on schools even as enrollment keeps falling.

The enduring gap between school spending and student performance should have destroyed by now Connecticut's longstanding presumption that spending equals education. But the presumption is sustained by the influence of the presumption's main beneficiaries -- members of teacher unions -- and by the public's not wanting to acknowledge education's decline. For doing so might lead to other troubling realizations.

One such troubling realization would be that teacher pay has to keep being raised not because teachers are successful but because students are making their jobs insufferable.

Teachers are leaving the profession and recruiting good candidates for teaching jobs is a struggle because many more students arrive in school ignorant of the basics they once learned at home and because many others seriously misbehave, even violently, or are chronically absent.

In these circumstances even the best teachers can't get good results, and even the worst teachers may be considered essential because there are no replacements.

For similar reasons police work in Connecticut also faces a staffing problem, especially in the cities. Who wants to "serve and protect" when the work is less appreciated and more dangerous?

xxx

Everywhere more people are behaving badly and seem full of rage -- not just on the road and in politics but in ordinary life as well. Hence, for example, Connecticut state government’s decision to allow municipalities to install "red light cameras" where motorist misconduct is worst.

Few people in authority acknowledge what is going on. Those who do sense that something is seriously wrong attribute it to the disruptions of the recent virus epidemic. While government's main responses to the epidemic were indeed mistaken and damaging -- school and commercial shutdowns and near-compulsory submission to inadequately tested vaccines -- the bad trends, including educational decline, were in place long before the epidemic. Signs of social disintegration are almost everywhere.

Everything starts with children. So where are all the messed-up kids coming from? Government isn't asking.

Throwing more money at teachers and police, as Connecticut is doing, may keep them on the job a while longer but it doesn’t answer the question and won’t make their jobs easier.

Southport, Conn.-based Sturm, Ruger & Co.’s MK II 22/45 target pistol. Despite the departures in recent decades from a state that used to be famous for firearms manufacturing, several major gun makers still retain a presence in Connecticut, including Sturm, Ruger; Colt, Charter Arms and Mossberg.

Maybe there is a hint about social disintegration in a recent study by the state Office of Legislative Research, analyzed last monthby Marc E. Fitch of the {conservative} Yankee Institute's Connecticut Inside Investigator.

The study tends to confirm complaints made in February by city mayors and police officials that since gun crime in Connecticut is committed disproportionately by repeat offenders, prosecutors and courts aren't taking gun crime seriously enough.

The OLR study found that from 2013 through 2022 two-thirds of gun-related criminal charges brought by police in Connecticut were dropped, usually as part of plea bargains gaining convictions on charges considered more serious.

The criminal-justice system runs on plea bargaining, so when most crimes get to court they are "discounted." While some arrests may involve "overcharging" by police -- adding charges that are more or less redundant -- a gun charge can be redundant only if the state thinks, for example, that it doesn't matter much if an assault or a robbery was committed with a gun as long as a conviction for assault or robbery can be achieved.

Of course, if state policy considered a gun offense to be just as serious as an assault or robbery, or even more so, and demanded that it be prosecuted just as seriously, and if conviction on a gun charge carried a mandatory long prison sentence, gun crime might diminish substantially.

Instead state legislators keep passing laws to impede gun ownership by the law-abiding and then boast about reducing the prison population even as repeat offenders, including gun criminals, remain free.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years. (CPowell@cox.net).

Podcast: 'Ideas actually matter’

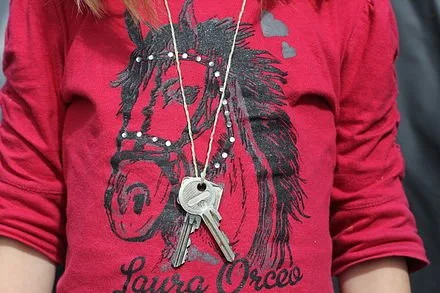

In this c. 1772 portrait by John Singleton Copley, Samuel Adams points at the Massachusetts Charter, which he viewed as a constitution that protected the people’s rights.

From Lapham’s Quarterly:

“‘I think that I started the book,’ historian Stacy Schiff says of The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams, ‘with this thirst for somebody who—I’ve just been writing about the Salem witch trials for many years. And I was looking for someone who had the courage of his convictions, to stand up and take an unpopular stand, which is something that takes a very long time for anyone to do in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1692, when it was very dangerous to take that stand. As it is dangerous again in the 1760s. And Adams very much fit that description. The more time I spent with him, the more time I was convinced and remain convinced that he teaches you that one person can actually make a difference and that ideas actually matter.”’

Lewis H. Lapham speaks with Stacy Schiff, author of The Revolutionary: Samuel Adams

At maximum fragrance

“Morning at the Creek” (oil on gesso board), by Massachusetts painter Sue Dragoo Lembo, at Alpers Fine Art, Rockport, Mass.

David Warsh: For the rest of us, a look at economists and what they do

Robert M. Solow in 2008

Somerville, Mass.

It defies credulity to say that Robert M. Solow’s most recent book is his best book to date, but, at least for certain practical purposes, this is the case. He will turn 99 next month. His four earlier books were written for other economists, beginning with Linear Programming and Economic Analysis, with Paul Samuelson and Robert Dorfman, in 1958; and Growth Theory: An Exposition (1970, expanded second edition, 2006).

Three very short books – The Labor Market as a Social Institution (Blackwell, 1990); Learning from “Learning By Doing” (Stanford, 1997) and Monopolistic Competition and Macroeconomic Theory (Cambridge, 1998) – approachable as they are, were also intended to influence professional audiences. There is no volume of collected papers, though many important papers exist to collect. Similarly, Solow has declined all offers to collect his popular reviews and essays, though many are classics of the sort.

Thus, Economists (Yale, 2019) is Solow’s first book written for a broad audience of intelligent citizens, outsiders and insiders, who are genuinely interested in what economics as a professional discipline exists to say and to do. The only barrier to entry is the price, $43 new, though copies can be obtained on second-hand markets for less and borrowed from many good libraries.

Economists is a book of photographic portraits of contemporary economists, designed for coffee tables display. What makes it worth reading, as opposed to slowly leafing through the ingenious photographs, is the introductory essay by Solow, and the answers to the questions he put to each subject, their replies carefully composed and printed on the page facing each subject’s portrait. The result is “A unique and illuminating portrait of economists and their work,” in the words of its editor, Seth Ditchik.

To recap briefly, Solow is the senior statesman of all academic economics. He dropped out of college after Pearl Harbor, returning after the war to study economics at Harvard. He joined the faculty of The Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1951, where one way or another, he has been ever since. A Nobel laureate himself, in 1987, he taught four others along the way: George Akerlof, Joseph Stiglitz, Peter Diamond, and William Nordhaus. He remains intellectually nimble.

The book has its beginnings at a dinner party on Martha’s Vineyard some years ago. Seated next to him was Mariana Cook, a celebrated fine-art photographer, who with her husband also has a summer home on the island. She mentioned she had recently published a book of portraits of contemporary mathematicians. Solow rejoined, “Why not do one of economists?” He quickly found himself involved in more ways than one.

Solow explains in his introduction:

Naturally I had to ask myself: Was making a book of portraits of academic economists a useful or reasonable or even a sane thing to do? I came to the conclusion that it was, and I want to explain why. For a long time it has bothered me, as a teacher of economics, that most Americans – even those who, a long time ago, had wandered through an economics course – had no clear idea of what economics is and what economists do. That is not surprising. The only contact most of us have with economics and economists is through sound bites on television, radio, or in a newspaper These snippets are usually about what the stock market has done or might do, or perhaps about next quarter’s gross domestic product. But only a tiny fraction of academic economists spend their professional time thinking about the stock market or forecasting GDP. So I suspect that the general image of what economists do and what economics is about is way off-base.

Economists is designed to redress that. Ninety superb portraits of ninety economists, young and old, each having been recognized by one or more of the profession’s highest honors, and, taken as a group, representative of the increasingly broad spectrum of concerns to have come under economists’ lenses. I have appended their names at the bottom of this newsletter, since I think it is not possible to find them otherwise outside the book. If you are a kdnowledgeable economist, you will see what I mean about the extent of the spectrum; you will also notice there are few economists teaching in Europe on the roster, because it is a long way for photographer Cook to have traveled.

In my favorite exchange, Solow asks Hal Varian, chief economist at Google and professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley:

Thirty years ago, you wrote a very successful microeconomics textbook. If you were to start over today, after your experience with Google, would you do it very differently?

Varian replies:

[T]hat is now in its ninth edition. A colleague once explained to me that by the time the tenth edition comes around “having a successful textbook is like being married to a wealthy person you don’t like much anymore….”

Lucky for me I had two big breaks. The first was bumping into Eric Schmidt in 2001, shortly after he joined “this cute little company called Google.” He invited me to come spend some time there. I thought I would spend a year there and write a book about yet another Silicon Valley start-up. Well, here I am fifteen years later, and I still haven’t gotten around to writing that book.

But I sure learned a lot. Quite a bit…got folded into my textbook. I wrote a couple of new chapters devoted to network effects, auction design, matching mechanisms, and switching costs. The old chapters got updated to illustrate novel applications of work-horse concepts like marginal cost and marginal value….

Then I got lucky again: the Great Recession hit. My book is about microeconomics, not macroeconomics, but even so there were a lot of issues that suddenly showed up in the economy that somehow weren’t discussed in the text. How could I have missed talking about “counter-party risk” or “financial bubbles?”… So I added some discussion about these topics to the text….

Along with theory, businesses need measurement. Today, with all the sensors and system available, collecting data had become more inexpensive than ever before…. Google does about ten thousand experiments a year.; the knowledge gained from these experiments feeds back into design, allowing continual improvement in product offering.

Great stuff! Read the book if you can. See how many of those found there you know. It made me long for the old days, when Economic Principals was a newspaper column, approaching topics like these from slightly different angles, accompanied by caricatures supplied by Pulitzer Prize-winning Boston Globe cartoonist Paul Szep!

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

MIT’s then-new Cambridge campus, in 1916. Harvard Bridge, named after John Harvard, the founder of Harvard University, is in the foreground, connecting Boston to Cambridge.

Of blueberries and sunburns

“Summer Twilight, A Recollection of a Scene in New-England’’ (oil on wood, 1834), by British-born American painter Thomas Cole (1801—1848), of the Hudson River School of painters

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal 24.com

As we move deeper into high summer, the green of the trees and grass is less intense, as are the scents of flowers and the volume of birdsong. Soon the goldenrod will blaze by the roads. On some days we settle into an agreeable torpor, perhaps more socially acceptable in July than in any other month in our workaholic nation. And it’s a time in which to read long novels, biographies and histories, albeit nodding off from time to time while doing it.

Ah, cookouts! The smell of burning flesh. Yellow jackets! Ants! Snakes (usually just garter snakes)! The distinctive smell of lighter fluid to ignite the charcoal. Squirrels eyeing the proceedings, ready, like the birds, to swiftly move in for any food detritus we accidentally left behind.

One of the pleasures of summer in New England is stopping by blackberry, blueberry and raspberry bushes and feeding yourself with these tart or sweet “antioxidant-rich superfoods”. By the way, wild blueberries, which famously cover a lot of ‘’barrens’’ in Downeast Maine, taste better than the cultivated ones.

A walk on a beach this summer, or along many otherwise pretty roads, shows you how urgently Rhode Island needs a bottle bill.

Do you still follow those old summer myths – e.g., that swimming after eating will give you cramps that could end up drowning you? No it won’t. Or that getting a tan is healthy. “You look healthy!, ‘’ our parents used to say to our sunburned faces, in a mistake that you can trace back to the 1920’s, when having a tan started to be associated with the leisure time of the affluent rather than with farmers and day laborers. Getting your tan in such sexy places as Florida, California and the French Riviera gave you a particular status.

Now, after decades of skin-cancer removals, a couple rather gory, I head for the shade as much as I can.

Religious revival summer camps

Gingerbread Cottages at Wesleyan Grove, in Oak Bluffs, on Martha’s Vineyard. Oak Bluffs was a major Protestant revival summer community starting in the 19th Century.

Andy Miller/Markian Hawryluk: Do not-for-profit hospitals deserve their big tax breaks?

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

“With so many Americans struggling with medical debt and access to care, the need for hospitals to give back as much as they take grows stronger every day.”

—Vikas Saini, president of the Needham, Mass.-based Lown Institute

POTTSTOWN, Penn.

The public school system here had to scramble in 2018 when the local hospital, newly purchased, was converted to a tax-exempt nonprofit entity.

The takeover by Tower Health meant the 219-bed Pottstown Hospital no longer had to pay federal and state taxes. It also no longer had to pay local property taxes, taking away more than $900,000 a year from the already underfunded Pottstown School District, school officials said.

The district, about an hour’s drive from Philadelphia, had no choice but to trim expenses. It cut teacher aide positions and eliminated middle school foreign language classes.

“We have less curriculum, less coaches, less transportation,” said Superintendent Stephen Rodriguez.

The school system appealed Pottstown Hospital’s new nonprofit status, and earlier this year a state court struck down the facility’s property-tax break. It cited the “eye-popping” compensation for multiple Tower Health executives as contrary to how Pennsylvania law defines a charity.

The court decision, which Tower Health is appealing, stunned the nonprofit hospital industry, which includes roughly 3,000 nongovernment tax-exempt hospitals nationwide.

“The ruling sent a warning shot to all nonprofit hospitals, highlighting that their state and local tax exemptions, which are often greater than their federal income tax exemptions, can be challenged by state and local courts,” said Ge Bai, a health-policy expert at Johns Hopkins University.

The Pottstown case reflects the growing scrutiny of how much the nation’s nonprofit hospitals spend — and on what — to justify billions in state and federal tax breaks. In exchange for these savings, hospitals are supposed to provide community benefits, like care for those who can’t afford it and free health screenings.

More than a dozen states have considered or passed legislation to better define charity care, to increase transparency about the benefits hospitals provide, or, in some cases, to set minimum financial thresholds for charitable help to their communities.

The growing interest in how tax-exempt hospitals operate — from lawmakers, the public, and the media — has coincided with a stubborn increase in consumers’ medical debt. KFF Health News reported last year that more than 100 million Americans are saddled with medical bills they can’t pay, and has documented aggressive bill-collection practices by hospitals, many of them nonprofits.

In 2019, Oregon passed legislation to set floors on community benefit spending largely based on each hospital’s past expenditures as well as its operating profit margin. Illinois and Utah created spending requirements for hospitals based on the property taxes they would have been assessed as for-profit organizations.

And a congressional committee in April heard testimony on the issue.

“States have a general interest in understanding how much is being spent on community benefit and, increasingly, understanding what those expenditures are targeted at,” said Maureen Hensley-Quinn, a senior director at the National Academy for State Health Policy. “It’s not a blue or red state issue. It really is across the board that we’ve been seeing inquiries on this.”

Besides providing federal, state, and local tax breaks, nonprofit status also lets hospitals benefit from tax-exempt bond financing and receive charitable contributions that are tax-deductible for the donors. Policy analysts at KFF estimated the total value of nonprofit hospitals’ exemptions in 2020 at about $28 billion, much higher than the $16 billion in free or discounted services they provided through the charity care portion of their community benefits.

Federal law defines the sort of spending that can qualify as a community benefit but does not stipulate how much hospitals need to spend. The range of community benefit activities, reported by hospitals on IRS forms, varies considerably by organization. The spending typically includes charity care — broadly defined as free or discounted care to eligible patients. But it can also include underpayments from public health plans, as well as the costs of training medical professionals and doing research.

Hospitals also claim as community benefits the difference between what it costs to provide a service and what Medicaid pays them, known as the Medicaid shortfall. But some states and policy experts argue that shouldn’t count because higher payments from commercial insurance companies and uninsured patients paying cash cover those costs.

Bai, of Johns Hopkins, collaborated on a 2021 study that found for every $100 in total spending, nonprofit hospitals provided $2.30 in charity care, while for-profit hospitals provided $3.80.

Last month, another study in Health Affairs reported substantial growth in nonprofit hospitals’ operating profits and cash reserves from 2012 to 2019 “but no corresponding increase in charity care.”

And an April report by the Needham, Mass.-based Lown Institute, a health-care think tank, said more than 1,350 nonprofit hospitals have “fair share” deficits, meaning the value of their community investments fails to equal the value of their tax breaks.

“With so many Americans struggling with medical debt and access to care, the need for hospitals to give back as much as they take grows stronger every day,” said Vikas Saini, president of the institute.

The Lown Institute does not count compensating for the Medicaid shortfall, spending on research, or training medical professionals as part of hospitals’ “fair share.”

Hospitals have long argued they need to charge private insurance plans higher rates to make up for the Medicaid shortfall. But a recent state report from Colorado found that, even after accounting for low Medicaid and Medicare rates, hospitals get enough from private health insurance plans to provide more charity care and community benefits than they do currently and still turn a profit.

The American Hospital Association strongly disagrees with the Lown and Johns Hopkins analyses.

For many hospitals — after dozens of closures over the past 20 years — “just keeping your doors open is a clear community benefit,” said Melinda Reid Hatton, general counsel for the AHA. “You can’t focus entirely on charity care” as a measure of community benefit. Hospitals deliver nine times the community benefit for every dollar of federal tax avoided, Hatton said.

The 2010 Affordable Care Act, she noted, imposed additional community benefit mandates. Tax-exempt hospitals must conduct a community health needs assessment at least once every three years; establish a written financial assistance policy; and limit what they charge individuals eligible for that help. And they must make a reasonable attempt to determine if a patient is eligible for financial assistance before they take “extraordinary collection actions,” such as reporting people to the credit bureaus or placing a lien on their property.

Still, the Government Accountability Office, a congressional watchdog agency, argues that community benefit is poorly defined.

“They’re not requirements,” said Jessica Lucas-Judy, a GAO director. “It’s not clear what a hospital has to do to justify a tax exemption. What’s a sufficient benefit for one hospital may not be a sufficient benefit for another.” The GAO, in a 2020 report, said it found 30 nonprofit hospitals that got tax breaks in 2016 despite reporting no spending on community benefits.

The GAO then recommended Congress consider specifying the services and activities that demonstrate sufficient community benefit.

The tax and benefit question has become a bipartisan issue: Democrats criticize what they see as scant charity care, while Republicans wonder why nonprofit hospitals get a tax break.

In Georgia, Democratic lawmakers and the NAACP spearheaded the filing of a complaint to the IRS about Wellstar Health System’s nonprofit status after it closed two Atlanta-area hospitals in 2022. The complaint noted the system’s proposed merger with Augusta University Health, under which Wellstar would open a new hospital in an affluent suburban county.

“I understand you pledged over $800 million” in the deal with AU Health, state Sen. Nan Orrock, an Atlanta Democrat, told Wellstar executives at a recent legislative hearing, citing the system’s disinvestment in Atlanta. “Doesn’t sound like a nonprofit. It sounds like a for-profit approach.”

Wellstar said it provides more uncompensated health care services than any other system in Georgia, and that its 2022 community benefit totaled $1.2 billion. Wellstar attributed the closures to chronic financial losses and an inability to find a partner or buyer for the inner-city hospitals, which served a disproportionately large African American population.

In North Carolina, a Republican candidate for governor, state Treasurer Dale Folwell, said many hospitals “have disguised themselves as nonprofits.”

“They’re not doing the job. It should be patients over profits. It’s always now profits over patients,” he said.

Ideas for reforms, though, have run up against powerful hospital opposition.

Montana’s state health department proposed developing standards for community benefit spending after a 2020 legislative audit found nonprofit hospitals’ reporting vague and inconsistent. But the Montana Hospital Association opposed the plan, and the idea was dropped from the bill that passed.

Pennsylvania, though, has a unique but strong law, Bai said, requiring hospitals to prove they are a “purely public charity” and pass a five-pronged test. That may make the state an easier place to challenge tax exemptions, Bai said.

This year, the Pittsburgh mayor challenged the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center over the tax-exempt status of some of its properties.

Nationally, Bai said, “I don’t think hospitals will lose tax exemptions in the short run.”

But, she added, “there will likely be more pressure from the public and policymakers for hospitals to provide more community benefit.”

Andy Miller and Markian Hawryluk are KFF Health News reporters. KFF States editor Matt Volz contributed to this report.

Borders, seen and unseen

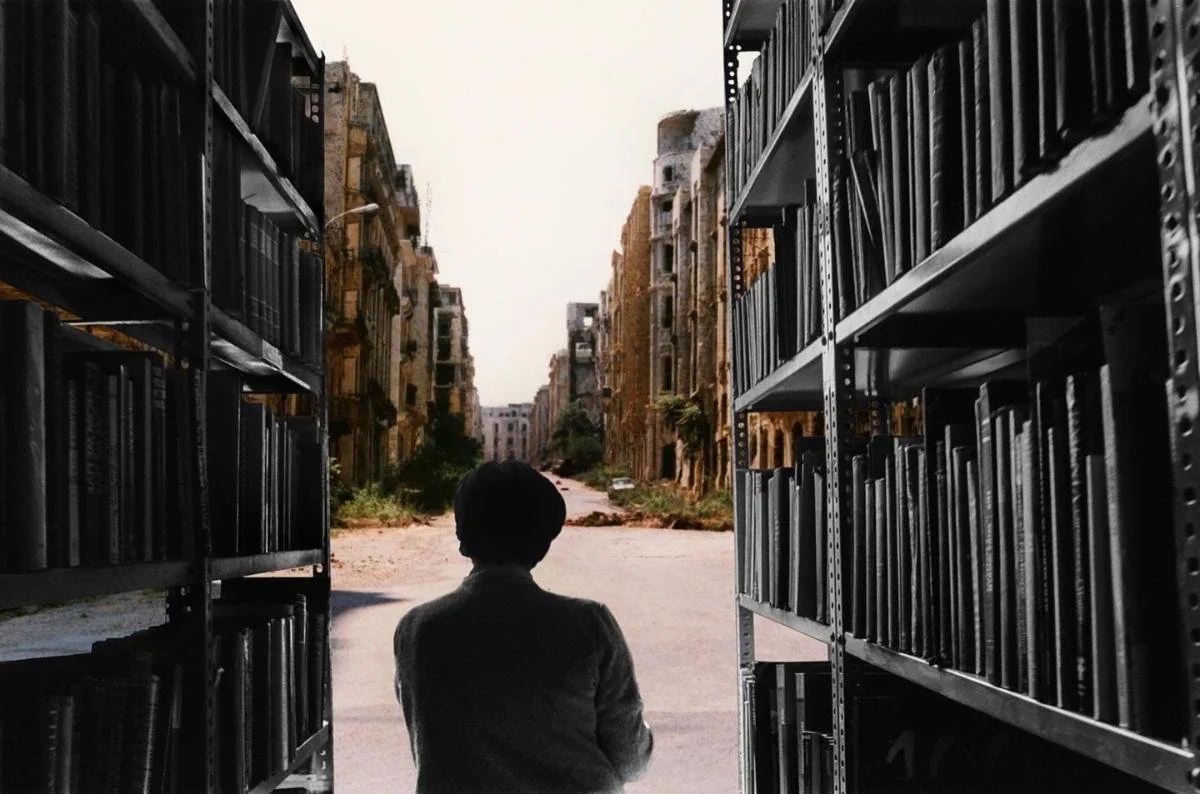

“The Beirut Memory Project #56, 2018-2021,’’ in the show “Disrupted, Borders,’’ by Ara Oshagan (digital collage, archival pigment print on velvet fine art paper), at the Armenian Museum of America, Watertown, Mass.

— Photo courtesy of the Armenian Museum of America

The museum says:

Oshagan is a "diasporic multi-disciplinary artist, curator, and cultural worker whose practice explores collective and personal histories of dispossession, legacies of violence, identity, and (un)imagined futures." The show "weaves together different geographies and spaces that considers the impact of borders (both visible and invisible) on our personal and collective history, past-present-future, and the disruption of dislocation."

Chris Powell: Wretched excess in the deep; Ellsberg’s lesson

— Photo by Jjm596

MANCHESTER, Conn.

As they descended toward their target 2½ miles under the North Atlantic, the five people aboard in the OceanGate Expeditions submersible vessel Titan were, at least superficially, aware of the risks they were taking for a close look at the wreck of RMS Titanic. They apparently had been compelled to provide a waiver of the company's liability, a waiver that repeatedly noted that the journey could be fatal.

But no one had been killed yet on such expeditions, and the five could consider themselves heroic explorers.

Since the wreck of the Titanic already had been discovered and extensively photographed, there was no necessity for the trip. To the vessel's pilot, the CEO of OceanGate Expeditions, it was a way of making a lot of money -- $250,000 per passenger. For his passengers the trip was more than a bit of arrogance and wretched excess.

Because the vessel imploded at great depth, there is little chance that its occupants suffered or even knew they were being killed. As many in the submarine service and industry in Connecticut know, death by implosion in the deep is instantaneous, a matter of milliseconds, too fast for the human brain to perceive.

In exchange for this mercy there will be no bodies to recover.

Many prayers sought the rescue of the occupants of the Titan, and their loss has been felt throughout the world. Instead of the granting of those prayers, the world has gotten two valuable reminders: first, of the limits imposed on mankind by the natural world, and second, of the incredibly precious smallness of the environment in which humans can survive. Despite many science-fiction movies to the contrary, the environmentalists are right in one respect: There is no Planet B.

While the ocean bottom holds many secrets, as the infinity of the universe does, mankind hardly needs to learn them as much as how to get along with itself and improve life where it can be lived: on the surface of the planet. Lives can be expended far better than in pursuit of another look at a shipwreck, and while the deep will always have to be challenged now and then, the poet George Gordon Byron (1788-1824) saw long ago that it would remain master.

Roll on, thou deep and dark blue Ocean -- roll!

Ten thousand fleets sweep over thee in vain.

Man marks the earth with ruin. His control

Stops with the shore. Upon the watery plain

The wrecks are all thy deed, nor doth remain

A shadow of man's ravage, save his own,

When, for a moment, like a drop of rain,

He sinks into thy depths with bubbling groan,

Without a grave, unknelled, uncoffined, and unknown.

xxx

How should the country remember Daniel Ellsberg, who died the other week?

As national security adviser in 1971, Henry Kissinger called him “the most dangerous man in America” for copying classified documents about the Vietnam war -- the Pentagon Papers -- and distributing them to news organizations.

Ellsberg was charged with espionage. But the Pentagon Papers revealed nothing of battlefield use to the enemy. Instead they showed that the administrations of Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard M. Nixon had been lying to the country about the war. Ellsberg was dangerous only to dishonest and criminal government officials.

Ellsberg might have been convicted except for the crimes the Nixon administration committed in pursuit of him, illegally wiretapping him and burglarizing his psychiatrist's office. So the charges against him were dismissed.

The Ellsberg affair may have been understood best by Nixon aide H.R. Haldeman, a criminal himself. He was taped telling Nixon: "To the ordinary guy, all this is gobbledygook. But out of the gobbledygook comes a very clear thing. .... You can't trust the government. You can't believe what they say. And you can't rely on their judgment. The implicit infallibility of presidents, which has been an accepted thing in America, is badly hurt by this, because it shows that people do things the president wants to do even though it's wrong, and the president can be wrong."

Has anything changed in 50 years?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics and other topics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

WPA art

"Skyscrapers” (circa 1937) (oil on canvas), by Joseph Stella (1877-1946), in the WPA Collection, at the T.W. Wood Gallery, Montpelier, Vt.

The Federal Art Project (1935-1943) was a New Deal program to fund America’s arts projects under the Works Progress Administration (WPA). It sustained some 10,000 artists during the Great Depression.

In 1940, Magnus Fossum, a WPA artist, copying the 1770 coverlet "Boston Town Pattern" for the WPA’s Index of American Design.

WPA Pump Station, in Scituate, Mass., built in 1938

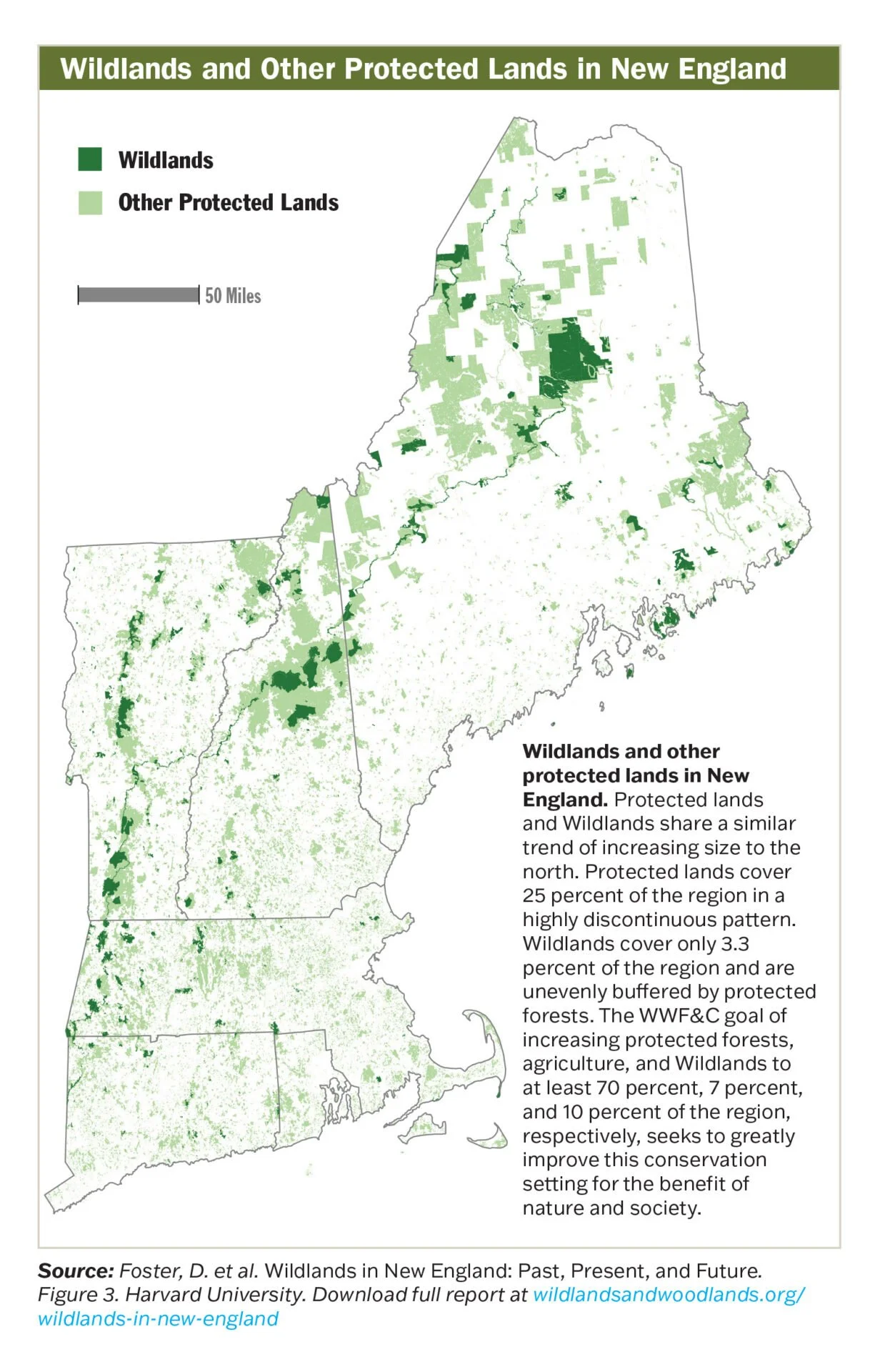

Study says New England needs to protect much more wildlands

Excerpted from ecoRI News by Rob Smith

PETERSHAM, Mass. (home of Harvard University’s research forest)

“New England isn’t conserving enough wildlands to mitigate climate change or meet conservation goals.

“That’s according to a new study released late last month by Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands and Communities (WWF&C), a coalition group of conservation organizations, educational institutions, local governments and private nonprofits.

“The first-of-its-kind analysis, performed jointly by (the} Harvard Forest of Harvard University, the Northeast Wilderness Trust and Highstead Foundation, examined how much wildlands — tracts of land where the management policy is to leave nature ‘alone’ and allow natural processes to prevail without human interference — are preserved across the region, and the answer is: not much.

“‘The wild condition of the land derives not from the land’s history, but from its freedom to operate untrammeled, today and in the future,’ wrote the study’s authors.

“The study lays out three criteria for land to meet its wildlands definition: the land must have a deliberate wildland purpose; it must be allowed to mature freely under prevailing environmental conditions with minimal human intervention; and it must be protected in perpetuity.

“The key factor in wildlands is time. In New England, where much of the land has been developed and used, wildlands are more likely to develop via natural rewilding, an ecological restoration practice that aims at reducing the influence of humans on ecosystems. Wildlands are more likely to look like recently clear-cut areas or former pastures than old growth forest.

“Only 1.3 million acres, around 3.3% of New England’s total land area, protects wildlands across 426 individual properties, with much of it limited to the remote and rural areas of the region, a band of land that stretches from northwestern Connecticut to Baxter State Park in Maine. Meanwhile WWF&C has set a goal of preserving 10% of the region as wildlands.’’

Diorama at the The Fisher Museum at the Harvard Forest, which offers exhibits on current research as well as 23 dioramas portraying the history, conservation and management of New England woodlands.

Llewellyn King: What happened to the kingmakers of journalism?

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

What happened to the kingmakers of journalism?

They seem to have died in 2011 with David Broder, of The Washington Post. In an age when columnists could still influence the flow of events, Broder stood out as much for what he wasn’t as for what he was.

He wasn’t, for example, a flashy writer. He didn’t have George Will’s turn of phrase. He didn’t add to the language like another kingmaker a generation before him, Walter Lippmann. Lippmann gave us “Great Society,” “Cold War” and “stereotype.”

What set Broder apart was the depth of his political reporting.

I worked with Broder at The Post, and he was relentless. If you were into politics, you were grist to his mill. From precinct captains to senators, they were all of interest to Broder, all worthy of his probing; all had a tale to tell, and Broder wanted to hear it.

Journalists at The Post used to drink in a genuinely downmarket bar called The New York Lounge, next to the better-known Post Pub, which, ironically, was eschewed by most of the editorial staff. Incongruously, Broder would be found there occasionally with some political apparatchik, notebook out and drinking a Diet Coke.

A reporter who traveled with Broder described how when they arrived in Midwestern city at 10 p.m., Broder got on the phone to see who of the local political establishment was up. It could have been a candidate or the local state party chairman; all were worth talking to in Broder’s world.

Whereas some newspaper grandees talked to presidents and the power elite (Lippmann helped Woodrow Wilson write his Fourteen Points, Joe Alsop shared sessions with Lyndon Johnson on the Vietnam War, and George Will rehearsed Ronald Reagan for his debates with Jimmy Carter), Broder reported relentlessly at all levels.

For all but the very end of his career, Broder worked as a reporter who wrote two columns a week. This industrious reporting underpinned the columns. They were magisterial and analytical.

You didn’t pick them up to be entertained but to get insight. That is where Broder’s strength lay, and that is what made him a kingmaker. Other political journalists and writers read Broder and were informed by him.

He told them which way the wind was blowing, and that filled their sails and influenced their work. Broder informed the political universe.

That is how he affected the careers of many a political grandee. He said in his studious and understated way, “Look at so-and-so.” And they looked, and then they wrote, and the landscape was changed.

I recall vividly a lunch at the Financial Times headquarters in London in 1975. Apart from FT people who included, as I recall, David Fishlock, the science editor, there was Virginia Hamill from The Washington Post News Service and Bernard Ingham, who was to become Margaret Thatcher’s press secretary.

The talk was about who would win the Democratic nomination. I had flown in from Washington the day before and had read Broder in The Post, so I blurted out, “Jimmy Carter.” The group looked askance and wanted to know why I had such a crazy idea. I replied, “Because Broder has discovered him.”

Broder’s influence was subtle but pervasive. He was the reporter’s reporter, the columnist’s columnist.

In the time since Broder’s death, everything has changed. There is so much commentary based on little reporting and politics is dominated by click-bait politicians — for example, Donald Trump, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert.

Analysis has been replaced with tribal bellowing, and social media has taken the debate off the editorial pages and handed it to influencers, who wouldn’t have gotten a letter to the editor published before the internet.

While dwelling on the kingmakers of old, it is worth mentioning the king-humblers, particularly Robert Novak. Novak got the goods.

Again, Novak wasn’t a great writer but was the source of hard gossip. If you wanted to point to wrongdoing in high places, a call to Novak would set the wheels of justice, or at least the downfall would be in motion.

Novak, a friend, thought that you should tell readers what they didn’t already know — and he did, often changing career trajectories for politicos.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Just ignore the Canadian smoke

Looking west toward the Adirondack Mountains and Lake Champlain from Charlotte's, Vt.

— Photo by Niranjan Arminius

Riverbank restoration project along the Connecticut River in Fairlee, Vt.

”Look. And smell. Breathe deeply. Feel the air; touch it now and sense its purity, its vigor, its super-constant rejuvenation (that supposedly has given Vermonters their long life — if you discount their stubbornness).’’

— Evan Hill, in The Connecticut River (1970

‘Dig out King George’s coffin'

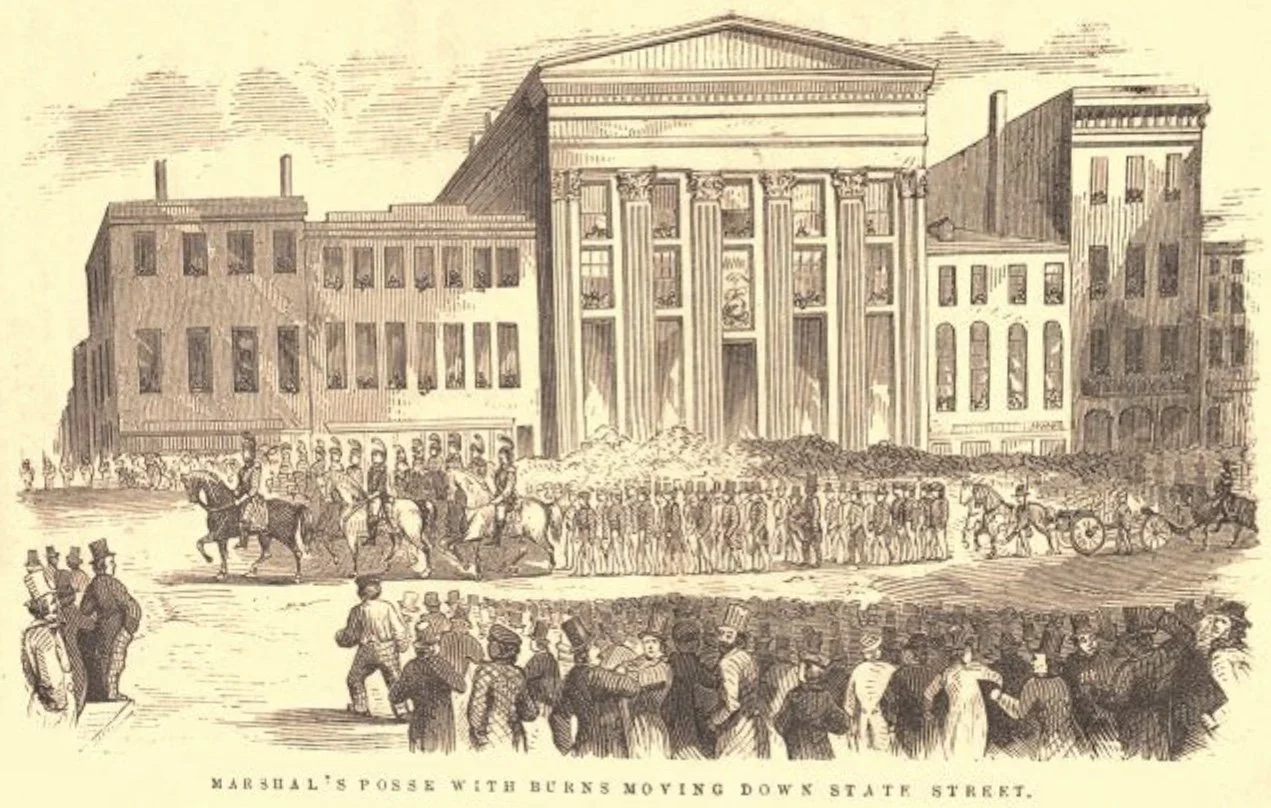

Federal marshals escort slave Anthony Burns to a ship amidst protests by Boston’s many abolitionists.

To get betimes in Boston town, I rose this morning early;

Here’s a good place at the corner—I must stand and see the show.

Clear the way there, Jonathan!

Way for the President’s marshal! Way for the government cannon!

Way for the Federal foot and dragoons—and the apparitions copiously

tumbling.

I love to look on the stars and stripes—I hope the fifes will play

Yankee Doodle.

How bright shine the cutlasses of the foremost troops!

Every man holds his revolver, marching stiff through Boston town.

A fog follows—antiques of the same come limping,

Some appear wooden—legged, and some appear bandaged and bloodless. 10

Why this is indeed a show! It has called the dead out of the earth!

The old grave—yards of the hills have hurried to see!

Phantoms! phantoms countless by flank and rear!

Cock’d hats of mothy mould! crutches made of mist!

Arms in slings! old men leaning on young men’s shoulders!

What troubles you, Yankee phantoms? What is all this chattering of

bare gums?

Does the ague convulse your limbs? Do you mistake your crutches for

fire—locks, and level them?

If you blind your eyes with tears, you will not see the President’s

marshal;

If you groan such groans, you might balk the government cannon.

For shame, old maniacs! Bring down those toss’d arms, and let your

white hair be; 20

Here gape your great grand—sons—their wives gaze at them from the

windows,

See how well dress’d—see how orderly they conduct themselves.

Worse and worse! Can’t you stand it? Are you retreating?

Is this hour with the living too dead for you?

Retreat then! Pell—mell!

To your graves! Back! back to the hills, old limpers!

I do not think you belong here, anyhow.

But there is one thing that belongs here—shall I tell you what it

is, gentlemen of Boston?

I will whisper it to the Mayor—he shall send a committee to England;

They shall get a grant from the Parliament, go with a cart to the

royal vault—haste! 30

Dig out King George’s coffin, unwrap him quick from the grave—

clothes, box up his bones for a journey;

Find a swift Yankee clipper—here is freight for you, black—bellied

clipper,

Up with your anchor! shake out your sails! steer straight toward

Boston bay.

Now call for the President’s marshal again, bring out the government

cannon,

Fetch home the roarers from Congress, make another procession, guard

it with foot and dragoons.

This centre—piece for them:

Look! all orderly citizens—look from the windows, women!

The committee open the box, set up the regal ribs, glue those that

will not stay,

Clap the skull on top of the ribs, and clap a crown on top of the

skull.

You have got your revenge, old buster! The crown is come to its own,

and more than its own.

Stick your hands in your pockets, Jonathan—you are a made man from

this day; 40

You are mighty cute—and here is one of your bargains.

— “A Boston Ballad” (1854), by Walt Whitman (1819-1992). This poem protests the case of escaped slave Anthony Burns in 1854, wherein a federal judge decreed Burns should be returned to his owner. Because Boston was strongly abolitionist, masses came out to jeer at the marshals who were charged with escorting Burns to the ship that would take him back to the South.

Before we go extinct, too

“Where Did the Dinosaurs Go?’’, by Connecticut artist and art teacher Lily Morgan, at The Norwalk (Conn.) Art Space.

The gallery says:

“Her work explores the relationship between abstraction, geometry and realism. Her paintings are built, layer by layer, and increase in complexity as they move towards the surface.’’

Coastal atmosphere

“William Shattuck: Paintings, Drawings and a Book!” (opening July 8) at Dedee Shattuck Gallery, Westport, Mass.

This quote from Mr. Shattuck is via the New Bedford Whaling Museum:

“Drawn in by color, composition and light, I find I’m also inspired just as easily by the temperature, the character of the air and atmosphere in the moment. I am not a Plein Air painter by any means, but I do spend a good deal of time walking through the fields, woods and marshes along this shoreline, noting the beauty and interplay between land, water and sky. I’ll sometimes make a line drawing with color notes, then eventually execute a finished piece in my studio.”

xxx

The Whaling Museum’s note:

“William Shattuck lives in Southeastern Massachusetts. His paintings reflect a fascination with the tidal marshes, estuaries and woodlands along that coastline. Having moved there in 1980 from New York, he has appreciated the changing patterns of light and weather throughout different seasons and times of day.’’

#Dedee Shattuck Gallery

#Westport, Mass.

#William Shattuck

Jim Hightower: Roger Payne was the man who discovered the music of whales

Humpback whale breaching

Via OtherWords.org

When you think of Americans whose music has made a lasting difference, you might think of Scott Joplin, Woody Guthrie, Maybelle Carter, Harry Belafonte … or Roger Payne.

Who? I came across Payne in an obituary reporting that he’d died at age 88 on June 10 at his home, in South Woodstock, Vt.

Yes, I occasionally scan the obits, not out of morbid curiosity, but because these little death notices encompass our people’s history, reconnecting us to common lives that had some small or surprisingly large impact.

Payne’s impact is still reverberating around the globe, even though few know his name. A biologist who studied moths, in the 1960s he chanced upon a technical military recording of undersea sounds that incidentally included a cacophony of baying, shrieking, mooing, squealing, and caterwauling.

They were the voices of humpback whales.

What others had considered noise “blew my mind,” Payne said, describing them as a musical chorus of “exuberant, uninterrupted rivers of sound.” His life’s work shifted from moths to whales and finally to the interdependence of all species..

At the time, whales were treated by industry and governments as dull, lumbering nuisances. But Payne’s musical instincts came into play, sensing that the “singing” of these magnificent mammals might reach the primordial soul of humans. Perhaps that Payne’s mother was a music teacher had a role.

So he collected their rhythmic, haunting melodies into a momentous 1970 recording titled Songs of the Humpback Whale. It became a huge best-seller, altered public perception, and spawned a global “Save the Whales” campaign — one of the most successful conservation movements ever.

Without writing or performing a single musical note, this scientist produced a truly powerful serenade from nature that continues to make a difference.

To connect with Roger Payne’s work and help extend his deep understanding that all of us beings are related, contact the global advocacy group he founded, Ocean Alliance, at whale.org.

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer, and public speaker.

Classic New England church in South Woodstock, Vt.

— Photo by Doug Kerr

#Roger Payne

#humpback whales

Information, please

We seek suggestions about interesting, dynamic people aged 70 or over, and in New England, to interview who are still working because they want to.

Please send suggested names to:

rwhitcomb4@cox.net

But beware the jungle

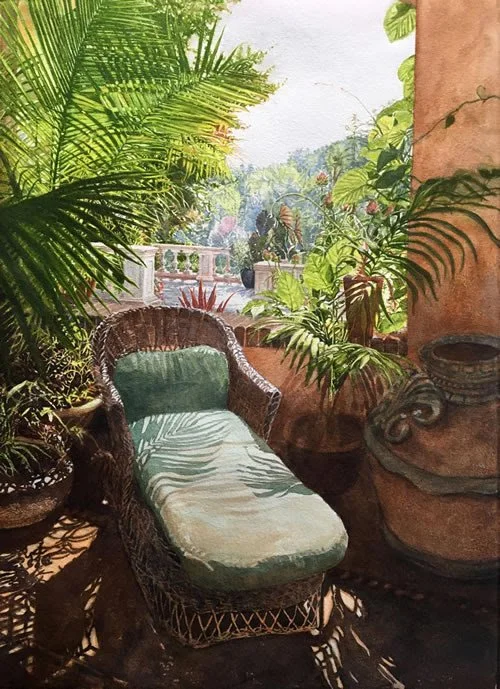

”Terrace Oasis” (watercolor), by West Barnstable, Mass.-based Brenda Bechtel, at the New England Watercolor Society Gallery’s 2023 “Celebrating New England’’ show, at the gallery, in Plymouth, Mass., through Sept. 7.

The gallery says:

“{The} exhibition … brings together 49 works from New England Watercolor Society members. The show is juried by Vladislav Yeliseyev, a Signature Member of the National Watercolor Society and the American Impressionist Society.’’

#Brenda Bechtel

#New England Watercolor Society