‘If I can find it’

Ralph E. Flanders

“I’m a New Englander and most of us are pack rats. We save everything, old bedsprings, empty cartons, clothing that went out of style fifty years ago, and trunks full of papers. Every once in a while it’s worth it if I can find what I’ll looking for.’’

— Ralph E. Flanders (1880-1970), U.S. senator from Vermont (1946-1959), mechanical engineer, industrialist. and writer. A Republican, he helped put an end to the career of the demagogic liar Sen. Joseph McCarthy (R.-Wis.) His base was Springfield, Vt.

Black River Falls, in Springfield, Vt., about 1910

Sinewy

“Untitled 375” (marine vinyl and walnut wall sculpture), by Derrick Velasquez, in his show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through July 15

The gallery says:

“Derrick Velasquez is known for abstract sculptures that employ industrial materials to investigate people’s relationships with the built environment. His ‘Untitled’ series draws on the sinews of the human body, each wall-mounted piece carefully made with layered vinyl strips to evoke distorted rainbows or the growth rings of trees.’’

Who will fall over first?

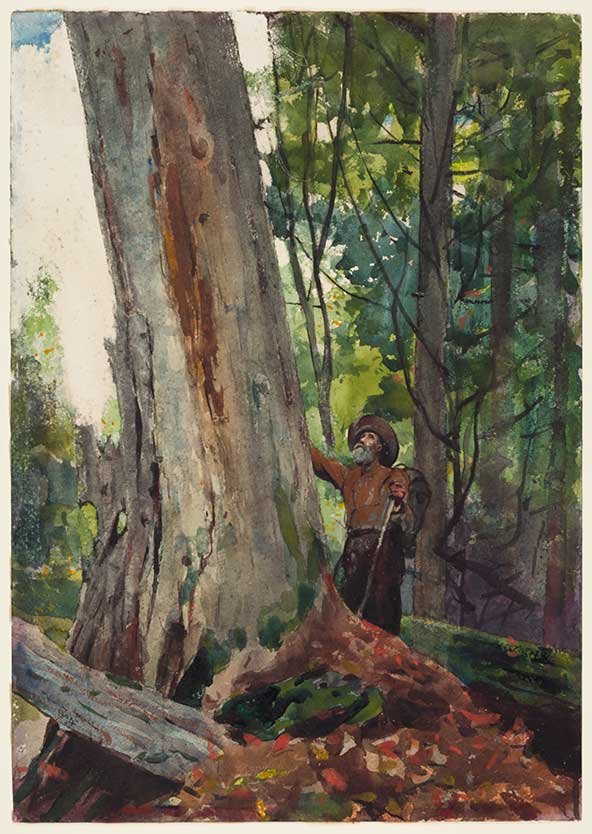

“Old Friends” (water color and opaque watercolor over old graphite), by Winslow Homer (1836-1910) in the “Watercolors Unboxed” show at the Worcester Art Museum, through Sept. 10. He was one of New England’s greatest painters.

Sam Pizzigati: CEO's of defense contractors get very, very rich off taxpayers

The Springfield (Mass.)Armory, more formally known as the United States Armory and Arsenal at Springfield, was the primary center for making U.S. military firearms from 1777 until its closing, in 1968.

At Westover Air Reserve Base, an Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC) installation in the Massachusetts communities of Chicopee and Ludlow. Established at the outset of World War II, Westover is now the largest Air Force Reserve base in the United States, home to about 5,500 military and civilian personnel, and covering 2500 acres.

U.S. Naval Station Newport, in Newport and Middletown, R.I., on Aquidneck Island

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Does anyone have a sweeter deal than military contractor CEOs?

The United States spent more last year on defense than the next 10 nations combined. A deal brokered the other week by the White House and House Republicans increases that amount even further — to $886 billion. Defense contractors will pocket about half of that.

Just eight years ago, the national defense community made do with over $300 billion less. But making do with “less” doesn’t come easy to corporate titans like Dave Calhoun, the CEO at Boeing, the nation’s second-largest defense contractor. Lockheed Martin is the biggest.

In March, Boeing’s annual filings revealed that Calhoun had missed his CEO performance targets and would not be receiving a $7 million bonus. As a result, Calhoun had to be content with a mere $22.5 million in 2022 — but to sweeten the deal, the Boeing board granted their CEO an extra stack of shares worth some $15 million at today’s value.

The Government Accountability Office may have had incidents just like that in mind when it urged the Pentagon to “comprehensively assess” its contract financing arrangements a few years ago.

This past April, the Department of Defense finally attempted to do it.

“In aggregate,” its report concludes, “the defense industry is financially healthy, and its financial health has improved over time.” But despite “increased profit and cash flow,” the DoD found, corporate contractors have chosen “to reduce the overall share of revenue” they spend on R&D.

Instead, they’re “significantly increasing the share of revenue paid to shareholders in cash dividends and share buybacks.” Those dividends and buybacks have jumped by an astounding 73 percent!

Contractor CEOs have been lining their pockets accordingly.

In 2021, the most recent year with complete stats, the nation’s top five weapons makers — Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, General Dynamics, and Northrop Grumman – grabbed over $116 billion in Pentagon contracts and paid their top executives $287 million, Pentagon-watcher William Hartung noted this past December.

Taxpayers subsidize these more-than-ample paychecks. Corporate giants like Boeing and Raytheon depend on government contracts for about half the dollars they rake in. For Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, and Northrop Grumman, it’s at least 70 percent.

“Huge CEO compensation,” Hartung observes, “does nothing to advance the defense of the United States and everything to enrich a small number of individuals.”

Even before Biden and Republicans agreed to increase spending, the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) calculated the “militarized portion” of the federal budget at 62 percent of all discretionary spending.

We have precious little to show for this enormous expenditure.

“The post-9/11 ‘War on Terror,’ for example, has cost more than $8 trillion and contributed to a horrific death toll of 4.5 million people in affected regions,” the IPS report notes. “Meanwhile, a U.S. military budget that outpaces Russia’s by more than 10 to 1 has failed to prevent or end the Russian war in Ukraine.”

So what can we do? The IPS analysts advocate reducing the national military budget by at least $100 billion and reinvesting the savings in social programs.

Progressive members of Congress, meanwhile, have also been pushing for a major change in contracting standards. Rep. Jan Schakowsky’s (D.-Ill.) “Patriotic Corporations Act” would give companies with smaller pay gaps between their CEOs and workers a leg up in the bidding for federal defense contracts.

Or we could go the Franklin D. Roosevelt route. In the year after Pearl Harbor, FDR issued an order limiting top corporate executive pay to $25,000 after taxes — a move Roosevelt said was needed “to correct gross inequities and to provide for greater equality in contributing to the war effort.”

By the war’s end, America’s wealthy were paying federal taxes on income over $200,000 at a 94 percent rate. That top rate hovered around 90 percent for the next two decades and helped give birth to the first mass middle class the world had ever seen.

Miracles can happen.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

The past isn’t past

From the current “Freedom” issue of Lapham’s Quarterly (laphamsquarterly.org), published by the American Agora Foundation and the most fascinating journal in America.

John S. Long: June walks on Gaspee Point

View of Gaspee Point from the north. Taken from across Passeonkquis Cove.

—Photo by Magicpiano

June 3, 2023

I’m walking on Gaspee Point, in Warwick, R.I., again. The wind is out of the northeast at a steady 16 mph, and it feels 10 degrees cooler. I see an Osprey atop its nest, but to my distress the nest seems otherwise unoccupied following days of unrelenting rain. Tomorrow is a full moon (a Strawberry Moon), and the tide is quite low. Gray clouds and a slate-gray Narragansett Bay stretch out, southeast, toward Colt State Park, in Bristol. Wind is whooshing through the trees. Otherwise, there’s silence except for a weed whacker sounding off above me on Gaspee Point’s high banks.

Only a handful of walkers are on the beach and the breakwater today. Iterations of waves intrude on the silence. Rain recommences, and I recall (from several weeks ago) a great cacophonous raft of Brant Geese set to embark on their stunning 2,500-mile migration to Greenland’s north coast nesting areas.

There are many seaside thickets, and pink, red and white beach roses bloom far back from high tide. Wind-driven drizzle comes, but I’m sheltered by a grove of American Elderberry trees.

There’s new sand in perfect smoothness--a beach nearly without human tracks.

June 10, 2023

I can hear a pair of Ospreys (cheereek, cheereek) on their nesting platform. Briefly, I think I’m seeing the female Osprey’s head as it pops up from the nest. Immediately, I’m wondering if there are baby Ospreys in the nest, even though it has been an cold fledgling season.

Now it’s high tide, and the wind’s from the southeast. Earlier this afternoon we had a passing shower.

Six Cormorants are resting and drying their wings on a broken erratic boulder 200 feet offshore. In winter water freezes within the boulder’s numerous cracks and pries it open oh so slowly.

A swath of the eastern sky is a robin’s egg blue with puffy clouds drifting in from the southeast.

On a shoal, edging the shipping channel, three quarters of a mile from shore is what had been Bullock Point Lighthouse--but only its granite pier remains. In my mind’s eye images of a Victorian gabled structure (1872) continue to fascinate me.

Walking north up the beach I note that one of the Ospreys (probably the male), with its wings nearly six feet across, brings new nesting branches clutched in his talons in a wide loop toward the nesting platform. A successful new family of Ospreys?

John S. Long lives in Warwick.

Relishing ruins

At “The Bells,’’ in Newport

— Photo by GoLocalProv.com

The amphitheater, artificial ruins in Maria Enzersdorf, Austria, built in 1810/11

— Photo byu C.Stadler/Bwag

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The state-owned, graffiti-rich carriage house and stables of a once stately Newport mansion, which was built in 1876 and called “The Bells’’ and torn down in the ‘60s, will finally be demolished. That’s after four young people who were playing there were injured when part of the roof collapsed. The structures probably should have been demolished years ago.

Newport has its fair share of residential monuments from the first Gilded Age (semi-officially roughly 1870-1900, though some extend it through The Twenties), but I’d guess that few if any, others are in such a mess as “The Bells.’’ The current Gilded Age, still going strong, began in the 1980s, when, under the Reagan administration, taxes were slashed for the very rich.

Places like “The Bells’’ lure young “explorers,” especially boys, intent on mischief or innocent fun. I well remember as a kid entering (i.e., trespassing) such decayed mansions along the Massachusetts Bay shoreline near our house. Most were, or had been, summer places. Perhaps some were abandoned, or just started to be neglected, when the owners ran out of money in The Depression. Most were gray-shingle houses that started to be put up after the Civil War. But some of the newer ones had Spanish Mission-style stucco walls, fountains and statuary, which were popular in The Roaring Twenties. Newly (if only briefly) rich people liked what they saw of these houses on Florida’s Gold Coast and in Los Angeles.

Kids would smoke in them (raising the danger of fire) or engage in such idiotic behavior as BB gun fights.

In the 18th Century and early 19th centuries in Europe, especially in England, there was a mania for building fake ruins; some draw tourists to this day. Maybe some falling-down Newport mansions can someday serve a similar purpose. Crumbling old houses covered with vines can look romantic, and are spawning grounds for entertaining ghost stories. Just kidding. The building inspectors probably wouldn’t allow it.

Art or food?

“The Tree of Crows” (oil on canvas), by Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840)

“Five crows, frock-coated in dignity, have arrived and sit upright and still on a bough. One thinks, ‘Oh beloved symbols of New England’ or ‘Drat those birds,’ depending upon whether one is planning a poem or a cornfield.’’

— Richard F. Merrifield (1905-1977), American essayist and novelist, in Monadnock Journal (1975). He lived in Keeene, N.H.

Stable conditions?

The Boston Athenæum building, as designed by Edward Clarke Cabot with additions by Henry Forbes Bigelow. The first part of the structure was put up in 1847. The institution itself was founded in 1807. It has become more public-friendly in recent years.

”New England is a finished place. Its destiny is that of Florence or Venice, not Milan while the American empire careens onward toward its unpredicted end. . . . It is the first American section to be finished to achieve stability in the conditions of its life. It is the first old civilization, the first permanent civilization in America.’’

Bernard DeVoto (1897-1955), American historian and essayist

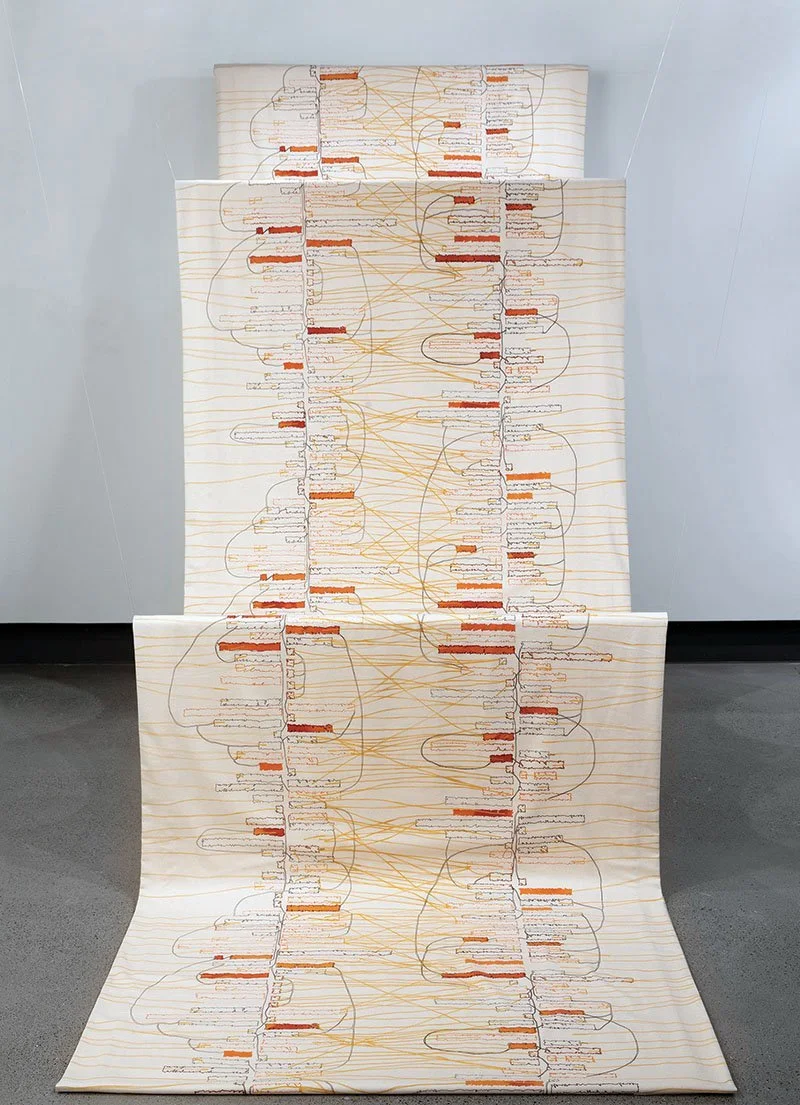

The architecture of language

From Massachusetts artist Sarah Hulsey’s show “Source Material,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through July 2

She says:

“My work is concerned with the architecture that underpins language, which we use effortlessly but with little awareness of its beauty and complexity. Even a simple sentence has layers and layers of organization, governed by a complex set of rules and interactions happening below the level of our conscious knowledge. Small pieces of information (atomic components, as it were) combine into ever larger units within the concurrent linguistic systems at play. These components are organized into elegant structures that exist only in the mind. In my artwork, I analyze these structures and create visual correlates, looking for poetry and resonance in the rich patterns that emerge. ‘‘

I compose abstract frameworks by building up nested and connected forms set within reticulated grids. Networks of these grids serve as armatures on which small elements abut, merge, and grow into higher order objects. In these pages, the underlying structures of sentences are segmented, excerpted, and then recombined into forms reflecting their core, essential relationships.

Chris Powell: Union secrecy; neither banned nor read; U.S. should pay its own way

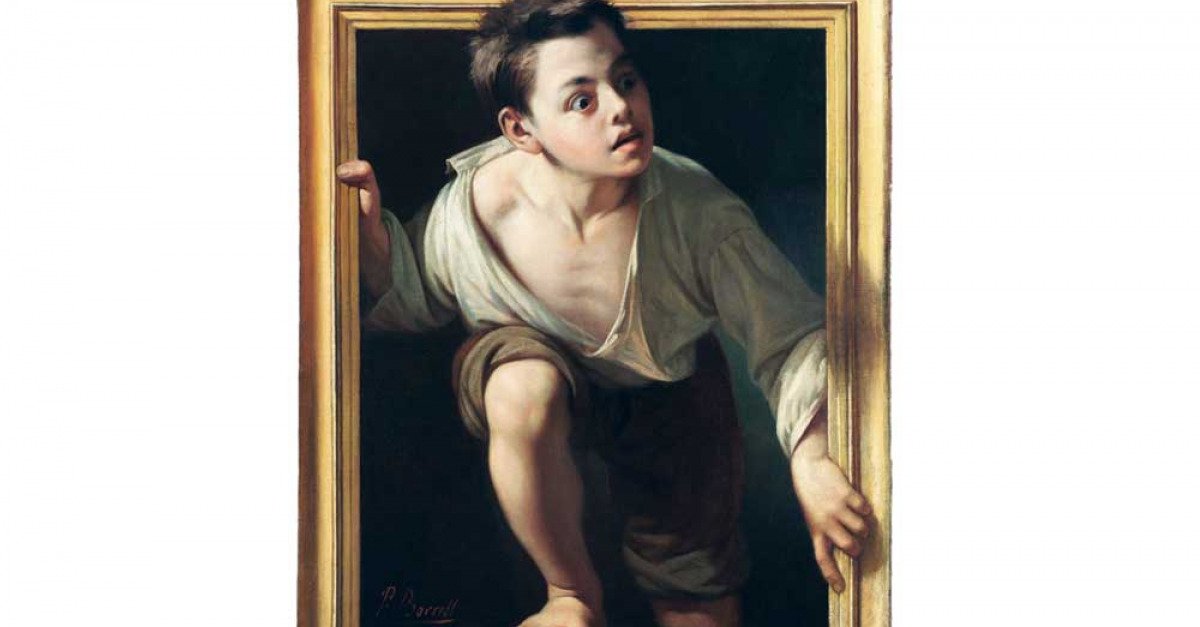

“The Secret,’’ by Moritz Stifter (1857-1905), German and Austrian painter

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Congratulations to Connecticut state Rep. Holly Cheeseman for exploding a spectacular hypocrisy of state government arising from its long subservience to the government employee unions.

Last week the state House of Representatives was debating legislation that would conceal from the public the home addresses of nearly every state and municipal government employee. This would have impaired accountability in government, but then that was the point. Cheeseman, a Republican from East Lyme, noted that two years ago the General Assembly and Gov. Ned Lamont enacted legislation to allow unions to obtain the same information in pursuit of enrolling and mobilizing government employees against the public interest.

Another Republican state representative, Craig Fishbein, of Wallingford, noted that the address-concealing bill as it was introduced originally would have concealed addresses for employees in only two state agencies, the state attorney general's office and the Department of Aging and Disability Services.

Other legislators complained that the expansion of the bill had never gotten a public hearing, though of course any such hearing would have been dominated by the unions. As they were about to be given another inch, the unions strove to grab another mile with the help of their tools in the legislature.

With debate making the legislation seem less sensible and starting to consume too much time in the General Assembly's always frantic hours just prior to mandatory adjournment, the House Democratic majority leader, Jason Rojas of East Hartford, took the bill off the agenda. But it will return sooner or later, maybe with a provision to make it illegal to know anything unflattering about a government employee.

xxx

Now that Newtown's Board of Education has decided against removing from the local high school library two books that some townspeople considered too sexually explicit, people are celebrating the defeat of what news organizations like to call book banning.

But the placement of books in a public school library is always fairly a matter of judgment about age-appropriateness, just as the placement of any book in a public library is always a matter of judgment on several levels. Anyone has a right to challenge these judgments, and democratic government is entitled to make them. There is no book banning here. The challenged books remain available outside the libraries to anyone who wants them. Indeed, challenges to books may increase their readership.

But that does not seem to have been the case with the two sexually explicit books at Newtown High School. As the school board voted to leave them in the library, the superintendent said one of the books had been checked out only once and the other not at all. The books may not exactly be great literature, and their sexual explicitness may not compare to the pornography to which high school students easily can gain access on the internet.

The lack of student interest in the challenged books invites another challenge to school officials. If there is so little interest in the books, why do they remain in the library? After all, every book that is stocked crowds out a book that isn't stocked. What isn't that considered book banning too?

xxx

While three of Connecticut's five U.S. representatives -- John Larson, Rosa DeLauro, and Jahana Hayes, all Democrats -- voted against the deal by President Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy to raise the federal debt ceiling, they almost certainly did so by arrangement with the Democratic House leadership and the White House.

That is, the legislation had enough votes so that the three from Connecticut could be spared, allowing the three House members to strike the usual poses in favor of the needy, whose assistance might be slightly reduced by the legislation.

A compelling question remains unanswered. If this assistance is so crucial, why is essentially infinite debt needed to finance it, transferring the cost to future taxpayers and countries that foolishly buy U.S. government bonds?

Why can't the United States pay its own way in the present and the usual way -- with taxes and economizing elsewhere in the government budget?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut politics and government for many years. (cpowell@cox.net)

David Warsh: It may be too late but here’s a suggestion on saving print newspapers

Newspapers rolling off the press

— Photo by Knowtex

1896 ad for The Boston Globe

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It may have been pure coincidence that strains on American democracy increased dramatically in the three decades after the nation’s newspaper industry came face to face with digital revolution. Then again, the disorder of the former may have something to do with the latter.

Since 2001, the last good year, daily circulation of major metropolitan newspapers has been plummeting. An edifying survey last year found that The Wall Street Journal, at the top of the field, delivered more print copies daily (697,493) than its three next three competitors combined: The New York Times (329,781), USA Today (149,233) and The Washington Post (149,040).

All but one of the top 25 newspapers reported declining print circulation year-over-year. The Villages Daily Sun, founded in 1997 in central Florida, not far north of Orlando, was up 3 percent, at 49,183, ahead of the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Is there still a market for print newspapers? Maybe, maybe not. There is probably only one good way to answer the question. I’d like to suggest a simple experiment: compete on price.

The New York Times Company bought The Boston Globe 30 years ago this week for $1.13 billion, in the last days of the golden age of print journalism. The Times ousted the Globe’s fifth-generation family management in 1999, installed a new editor in 2001, and, for 10 years, rode with the rest of the industry over the digital waterfall.

The Globe, whose 2000 circulation had been roughly 530,000 daily and 810,000 Sunday, broke one great story on the way down. Its coverage of the systemic coverup of clerical sexual abuse of minors in the Roman Catholic Church beginning in 2002 has reverberated around the world. The story produced one more great newspaper movie as well – perhaps the last — Spotlight. Otherwise the New York Times Co. mismanaged the property at every opportunity, threatening at one point to simply close it down. It finally sold its New England media holdings in 2013 to commodities trader and Boston Red Sox owner John W. Henry for $70 million.

Since then, the paper has stabilized, editorially, at least, under the direction of Linda Pizzuti Henry, a Boston native with a background in real estate who married Henry in 2009. Veteran editor Brian McGrory served for a decade before returning to column writing this year. Nancy C. Barnes was hired from National Public Radio to replace him; editorial page editor James Dao arrived after 20 years at the Times. A sustained advertising campaign and new delivery trucks gave the impression the Globe was in Boston to stay.

Henry himself showed some publishing flair, starting and selling a digital Web site, Crux, with the idea of “taking the Catholic pulse,” then establishing Stat, a conspicuous digital site that covers the biotech and pharmaceutical industries. Henry’s sports properties – the Red Sox, Britain’s Liverpool Football Club, a controlling interest in the National Hockey League’s Pittsburgh Penguins, and a 40 percent interest in a NASCAR stock car racing team, are beyond my ken.

There is, however, one continuing problem. The privately owned Globe is thought to be borderline profitable, if at all. It seems to have followed the Times Co. strategy of premium pricing. Seven-day home delivery of The Times now costs $1305 a year. Doing without its Saturday and overblown Sunday editions brings the price down to $896 for five days a week. The year-round seven days a week home delivery price for The Globe is posted in the paper as $1,612, though few subscribers seem to pay more than $1200 a year, to judge from a casual survey.

In contrast, six-day home delivery of WSJ costs $720 a year. The American edition of the Financial Times, in some ways a superior paper, costs $560 six days a week, at least in Boston. It is hard to find information about home-delivery prices for The Washington Post, now owned by Amazon magnate Jeff Bezos. But $170 buys out-of-town readers a year’s worth of a highly readable daily edition.

So why doesn’t The Globe take a deep breath and cut home-delivery prices to an annual rate of $600 or so, to bring its seven-day value proposition in line with those of the six-day WSJ and the FT? The Globe trades heavily on legacy access to wire services of both The Times and The Post; it is not clear how this would fit into such a bargain with readers. Long-time advertising campaigns would be required to make the strategy work.

That would be taking a leaf from The Times’s long-ago playbook. In 1898, facing falling ad revenues amid malicious rumors that it was inflating its circulation figures, publisher Adolph Ochs, who had bought the daily less than three years before, cut without warning its price from two cents to a penny, to the astonishment of his principal New York competitors on quality, The Herald and The Tribune. He quickly gained in volume what he gave up for the moment in revenue, raised the price a year later, and never looked back. The move has been hailed ever since as “a stroke of genius.”

Would it work today? It might. If it did, it would constitute a proof of concept, an example for all those other formerly great metropolitan newspapers to consider in hopes of creating a standard for two-tier home-delivery pricing: one price for the national dailies; a second, slightly lower price for the less-ambitious home-town sheet.

It might force The Times to cut back on its Tiffany pricing strategy, to take advantage of once-again growing home-delivery networks, and get print circulation increasing again, after two decades of gloomy decline.

Even digital publisher of financial information Michael Bloomberg might be persuaded to put his first-rate news organization to work publishing a thin national newspaper, on the model of the FT. Print newspapers have a problem with pricing subscriptions to their print daily papers. It is time for industry standards committees to begin considering the prospects.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

“Newspaper readers, 1840,’’ by Josef Danhauser

Mining the ‘microworld’

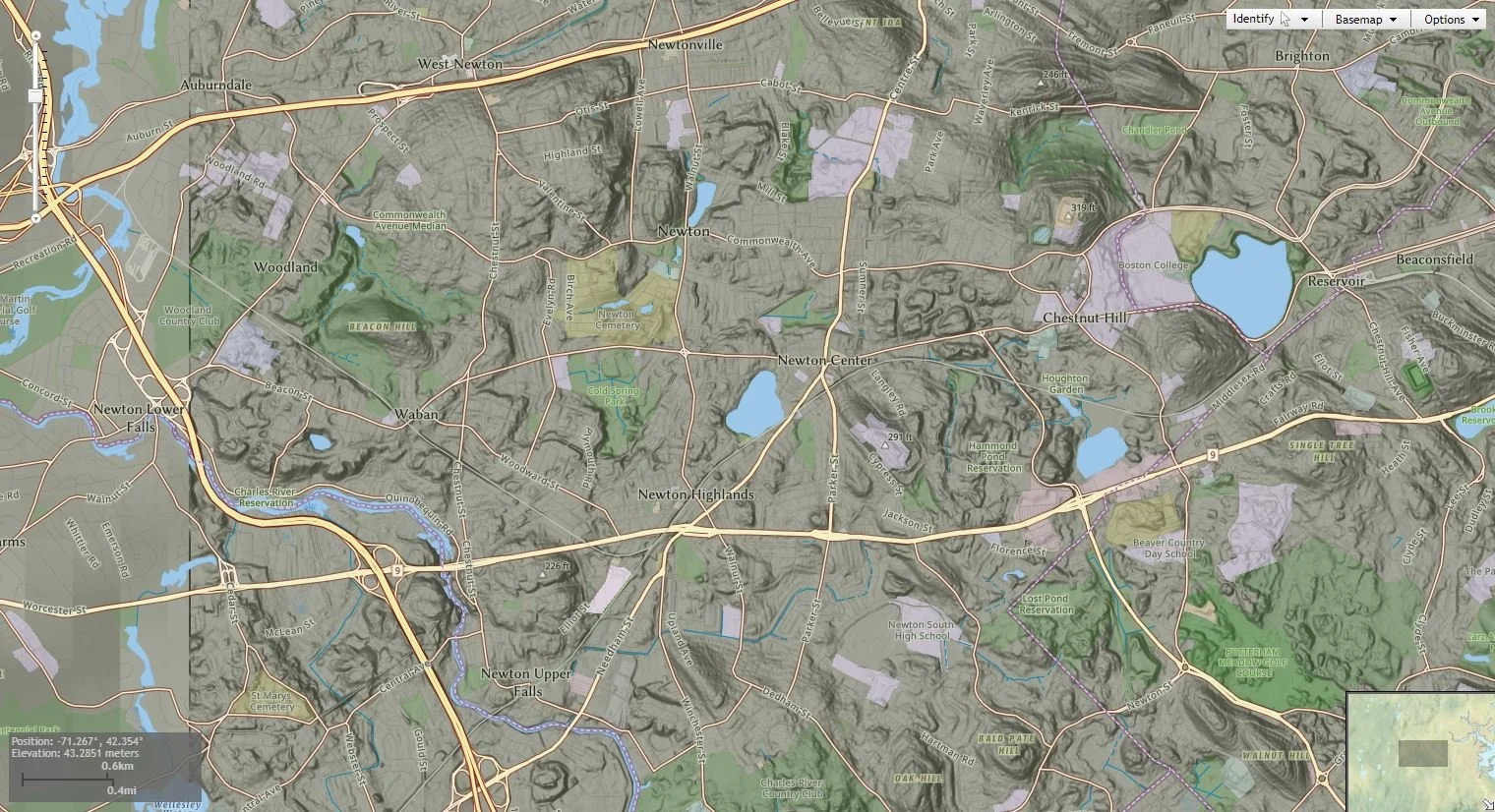

From Korean-American artist Miyoung So’s show “Yet to Be Seen,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, June 14-July 16

The gallery says:

“Inspired by fungal formations,’’ the show “features delicately detailed sculptural works constructed from hand-made cold porcelain and recycled materials. The artist muses, ‘As I traversed old wooden bridges, walked down roads lined with trees, and passed by my neighbors' houses, {in her hometown of Newton, Mass.} I noticed something ubiquitous: lichens, fungi, slime mold, and moss.’ She began to observe these small yet fascinating organisms closely, adjusting the zoom on her phone camera to capture their minute details. The microworld proved to be a wellspring of inspiration for her work.’’

From a National Centers for Environmental Information elevation model of Newton terrain

#So Miyoung #Boston Sculptors Gallery

From a bay’s sea, sky, sand and rocks

“Rock 234: Yellow Flag” (painting), by Tom Gaines (1935-2023), in the show “Tom Gaines: The Last Paintings,’’ at Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine. Mr. Gaines was based in New Jersey but also painted at his summer home, in Belfast, Maine.

He wrote:

“Since 2005, three major changes have taken place, which have brought me to where I am now… a series of more than 2,000 rock paintings.

“The first change came when I created, quite by accident, a different surface. I had attempted with mineral spirits to wipe out a color that I had allowed to dry for a few days. Some of the color remained, revealing layers of old and new color. This revelation of layers suggested erosion. I was so taken with the result that I purposely worked this way with subsequent paintings.

“The next change came while I was working on a series of interiors and decided to eliminate most of the subject matter. The result was a simpler, more geometric and more abstract composition. I worked this way for more than a year. Simplifying and layering.

“I made a third change while working in my studio in Belfast, Maine. I realized that I needed to prioritize my ideas regarding the relationship between subject matter and form. I found the simpler subject matter/composition from the sky, sea, sand, and rocks of Penobscot Bay.’’

#Corey Daniels Gallery #Tom Gaines

Penobscot Bay from Belfast

Blaisdell Residence, Belfast, from a circa 1920 postcard. It’s a Greek Revival mansion from the city's 19th Century shipbuilding boom. Known as The Williamson House (www.TheWilliamsonHouse.com) survives today as a Museum in The Streets landmark.

To promote ‘generous sentiments’

From the Constitution of Massachusetts, enacted in 1780:

“Wisdom and knowledge, as well as virtue, diffused generally among the body of the people, being necessary for the preservation of their rights and liberties; and as these depend on spreading the opportunities and advantages of education in the various parts of the country, and among the different orders of the people, it shall be the duty of legislatures and magistrates, in all future periods of this commonwealth, to cherish the interests of literature and the sciences, and all seminaries of them; especially the university at Cambridge {Harvard}, public schools and grammar schools in the towns; to encourage private societies and public institutions, rewards and immunities, for the promotion of agriculture, arts, sciences, commerce, trades, manufactures, and a natural history of the country; to countenance and inculcate the principles of humanity and general benevolence, public and private charity, industry and frugality, honesty and punctuality in their dealings; sincerity, good humor, and all social affections, and generous sentiments, among the people.’’

Green Mountain creepiness

From the “Haunted Vermont’’ show at the Bennington Museum, July 22-Dec. 31.

The Haunted Bridge, or Red Bridge, was a covered bridge that crossed the Walloomsack River just north of the Bennington Battle Monument. It was torn down around 1944. The caption for this postcard, c. 1920, reads: "The Haunted Bridge. On certain moonlight nights weird noises are said to have been heard in and around it. A phantom horseman is frequently heard clattering across and into a nearby farmyard."

The museum explains:

“Vermont has a long and storied history of otherworldly intrigue, ranging from accusations of witches in Pownal and vampires in Manchester, to Spiritualists communicating with the dead, haunted covered bridges, and our very own Bennington Triangle. Shirley Jackson, perhaps the greatest writer of the horror/gothic fiction genre in the 20th Century, lived and worked for most of her career in North Bennington. Drawing on this rich framework of historical tales of monsters, ghosts, missing persons and the occult, ‘Haunted Vermont’ will tell these stories and more.’’

Mixed messaging of vaccine skeptics sows seeds of doubt

An early 19th-Century satire of antivaxxers by Isaac Cruikshank

Headquarters, in Cambridge, Mass., of Moderna, one of the major COVID-19 vaccine makers

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

“It seems to me to be implying the government knows the vaccine to be unsafe” and that it’s “covering it up.’’

— Matt Motta, a political scientist at Boston University specializing in public health and vaccine politics

It was a late-spring House of Representatives hearing, where members of Congress and attendees hoped to learn lessons from the pandemic. Witness Marty Makary made a plea.

“I want to thank you for your attempts at civility,” Makary, a Johns Hopkins Medicine researcher and surgeon, said softly. Then his tone changed. His voice started to rise, blasting the “intellectual dishonesty” and “very bizarre” decisions of public health officials. Much later, he criticized the “cult” of his critics, some of whom “clap like seals” when certain studies are published. Some critics are “public health oligarchs,” he said.

Makary was a marquee witness for this meeting of the Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic. His testimony had the rhythm of a two-step — alternating between an extended hand and a harsh rhetorical slap. It’s a characteristic move of this panel, a Republican-led effort to review the response to the pandemic. Both sides of the aisle join in the dance, as members claim to seek cooperation and productive discussions before attacking their preferred coronavirus villains.

One target of the subcommittee’s Republican members has drawn concern from public health experts: COVID-19 vaccines. Because the attacks range from subtle to overt, there’s a fear all vaccines could end up as collateral damage.

During that May 11 hearing, Republican members repeatedly raised questions about coronavirus vaccines. Right-wing star Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R.-Ga.) emphasized the vaccines were “experimental” and fellow Georgia Republican Rep. Rich McCormick, an emergency room physician, argued the government was “pushing” Federal Drug Administration-approved boosters “with no evidence and possible real harm.”

Some Republican members, who have been investigating for months various pandemic-related matters, are keen to say they’re supportive of vaccines — just not many of the policies surrounding COVID vaccines. Rep. Brad Wenstrup (R.-Ohio), who chairs the subcommittee, has said he supports vaccines and claimed he’s worried about declining vaccination rates.

During the May hearing, he also two-stepped, arguing the COVID shots were “safe as we know it, to a certain point.” He questioned the government’s safety apparatus, including VAERS, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, a database that receives reports potentially connected to vaccines. He said the committee would be “looking” at it “to make sure it’s honest and to be trusted.”

It’s this two-step — at once proclaiming oneself in favor of vaccines, while validating concerns of vaccine-skeptical audiences — that has sparked worries of deeper vaccine hesitancy taking root.

“It seems to me to be implying the government knows the vaccine to be unsafe” and that it’s “covering it up,” said Matt Motta, a political scientist at Boston University specializing in public health and vaccine politics. The implication validates some long-held fringe theories about vaccinations, without completely embracing “conspiracism,” he said.

Vaccine skeptics run the gamut from individuals with scientific credentials who nevertheless oppose public health policies from a libertarian perspective to individuals endorsing theories about widespread adverse events, or arguing against the need for multiple shots. VAERS is a favorite topic among the latter group. When one witness testifying during the May 11 hearing attempted to defend covid vaccination policies, Taylor Greene cited the number of reports to VAERS as evidence of the vaccines’ lack of safety.

That muddles the purpose of the database, Motta said, which gathers unverified and verified reports alike. It’s a signal, not a diagnosis. “It’s more like a smoke alarm,” he said. “It goes off when there’s a fire. But it also goes off when you’ve left an omelet on the stove too long.”

In a March hearing focusing on school reopening policies, Democratic members of the panel and a witness from a school nurses association frequently touted the important role covid vaccines played in enabling schools to reopen. Wenstrup offered generalized skepticism. “I heard we were able to get more vaccines for the children,” he said. “We didn’t know fully if they needed it. A lot of data would show they don’t need to vaccinate.”

Witnesses can eagerly play into vaccine-skeptical narratives. After a question from Taylor Greene premised on the idea that the covid vaccines “are not vaccines at all,” and alleging the government is spreading misinformation about their effectiveness, Makary suggested that while he was not anti-vaccine, it was understandable others were. “I understand why they are angry,” he said, in response. “They’ve been lied to,” he said, before criticizing evidence standards for the newest covid boosters, tailored to combat emerging variants.

The signals aren’t lost on audiences. The subcommittee has, like most congressional panels, posted important moments from its hearings to Twitter. Anti-vaccine activists and other public health skeptics reply frequently.

“It’s hard for me to think of a historical analogue for this — it’s not often that we have a Congressional committee producing content that has its fingers on the pulse of the anti-vaccine community,” Motta wrote in an e-mail, after reviewing many of the subcommittee’s tweets. “The committee isn’t expressly endorsing anti-vaccine positions, beyond opposition to vaccine mandates; but I think it’s quite possible that anti-vaccine activists take this information and run with it.”

Motta’s concern is echoed by the panel’s Democratic members. “I pray this hearing does not add to vaccine hesitancy,” said Rep. Kweisi Mfume (D.-Md.), who represents Baltimore.

One witness reiterated that point. Many members “have a lot of skepticism about vaccines and were not afraid to express that,” Tina Tan, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases at Northwestern University, told KFF Health News. She testified at the hearing on behalf of the minority.

Polling is showing a substantial — and politically driven — level of vaccine skepticism that reaches beyond covid. A slim minority of the country is up to date on vaccinations against the coronavirus, including the bivalent booster. And the share of kindergartners receiving the usual round of required vaccines — the measles, mumps, and rubella, or MMR, inoculation; tetanus; and chickenpox among them — dropped in the 2021-22 school year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Support for leaving vaccination choices to parents, not as school requirements, has risen by 12 percentage points since just before the pandemic, mostly due to a drop among Republicans, according to a recent poll by the Pew Research Center.

And vaccine skepticism is resonating beyond the halls of Congress. Some state governments are considering measures to roll back vaccine mandates for children. As part of a May 18 procedural opinion, Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch cited two vaccination mandates — one in the workplace, and one for service members — and wrote that Americans “may have experienced the greatest intrusions on civil liberties in the peacetime history of this country.” He made this assertion even though American military personnel have routinely been required to get shots for a host of diseases.

“We can’t get to a spot where we’re implicitly or explicitly sowing distrust of vaccines,” cautioned California Rep. Raul Ruiz, the Democratic ranking member of the coronavirus subcommittee.

Darius Tahir is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter.

DariusT@kff.org, @dariustahir

‘Insistent materiality’

Work by the Modernist artist Elie Nadelman (1882-1946, American, born in Poland) in the show “Material Matters,’’ at the Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Conn., through Sept. 24.

The museum says:

“Nadelman is best known for his sculptural explorations of pure form. Melding classical source material and folk art, Nadelman’s sculptures range from idealized heads and animals to genre subjects drawn from everyday life, such as acrobats, circus performers, and dancers.

“Featuring more than twenty sculptures, this show showcases the artist’s experimentation with materials. In the early 1910s, he created idealized, classical heads in conventional materials such as bronze, marble, and stone. He expanded his practice by the end of the decade to include wood and plaster figural sculptures inspired by his experience of living in New York City. From the 1920s until the end of his career, Nadelman increasingly gravitated toward inexpensive, nontraditional materials. … The painted, textured, and weathered surfaces of Nadelman’s sculptures—their insistent materiality—are part and parcel of Nadelman’s modernity.’’

Llewellyn King: Smoke spreads amidst global warming but beware overzealous regulation

Smoke from Canadian forest fires in the Delaware River Valley. See New England’s “Dark Day’’.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The smoke from wildfires in Canada that has been blown down to the United States, choking New York City and Philadelphia with their worst air quality in history and blanketing much of the East Coast and the Midwest, may be a harbinger for a long, hot, difficult summer across America.

It could easily be the summer when the environmental crisis, so easily dismissed as a preoccupation of “woke’’ Greens and the Biden administration, moves to center stage. It could be when America, in a sense, takes fright. When we realize that global warming is not a will-or-won’t-it-happen issue like Y2K at the turn of the century.

Instead, it is here and now, and it will almost immediately start dictating living and working patterns.

In an extraordinary move, Arizona has limited the growth in some subdivisions in Phoenix. The problem: not enough water. Not just now but going forward.

The floods and the refreshing of surface impoundments, such as Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the nation’s largest reservoirs, haven’t solved the crisis.

All along the flow of the Colorado River, aquifers remain seriously depleted. One good, rainy season, one good snowpack may recharge a dam, but it doesn’t replenish the aquifers that hydrologists say have been undergoing systematic depletion for years.

An aquifer isn’t just an underground river that runs normally after rainfall. It takes years to recharge these great groundwater systems. These have been paying the price of overuse for years; across Texas and all the way to the Imperial Valley, in California, unseen damage has been done.

It isn’t just water that looms as a crisis for much of the nation, there is also the sheer unpredictably of the weather.

I talk regularly with electric- and gas-utility company executives. When I ask them what keeps them awake at night, they used to respond, “Cybersecurity.” Recently, they have said, “The weather.”

This year, we are entering the tropical-storm season with unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Atlantic and the Pacific. The doleful conclusion is that these will signal severe and very damaging weather activity across the country.

The utilities have been hardening their systems, but electricity is uniquely affected by weather. The dangers for the electricity industry are multiple and all affect their customers. Too much heat and the air-conditioning load gets too high. Too much wind and power lines come down. Too much rain and substations flood, poles snap and there is crisis, from a neighborhood to a region.

In the electricity world, the words of John Donne, the 16th-Century English metaphysical poet, apply, “No man is an island entire of itself.”

There is another threat that the electricity-supply system will face this summer if the weather is chaotic: overzealous politics and regulation.

It is the electric utilities that are most identified in the public mind with climate change. The public discounts the myriad industrial processes as well as the cars, trucks, bulldozers, trains and ships that lead to the discharge of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Instead, it is utilities that have a target pinned to them.

A bad summer will lead to bad regulatory and bad political decisions regarding utilities.

Foremost are likely to be new attacks on natural gas and its supply chain, from the well, through the pipes, into the compressed storage, and ultimately to combustion turbines.

At this time, natural gas – about 60-percent cleaner than coal — is vital to keeping the lights on and the nation running when the wind isn’t blowing, or the sun has set or is obscured.

The energy crisis that broke out in the fall of 1973, and lasted pretty well to the mid-1980s, was characterized by silly over-reactions. First among these was probably the Fuel Use Act of 1978, which got rid of pitot lights on gas stoves and even threatened the eternal flame at Arlington Cemetery.

It also accelerated the flight to coal because, extraordinarily, that was the time of the greatest opposition to nuclear power — from the environmental communities.

This summer may be a wakeup for climate change and how we husband our resources. But wild overreaction won’t quiet the weather.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and a long-time editor, writer and consultant in the international energy sector. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

#global warming #Llewellyn King #electric utilities

Animal rights and abuses in New Bedford show

“Massachusetts State of the Union,’’ by Providence/West Palm Beach artist Jane O’Hara, in the show of the same name at the New Bedford Art Museum, through Aug. 20

— Photo courtesy New Bedford Art Museum.

The museum explains that the show looks at animal rights and the complex relationship between humans and other animals. “Covering the 50 states of the union, O'Hara's work examines animal rights abuses through the lens of classic ‘wish-you-were-here postcards.’’’

#Jane O’Hara #New Bedford Art Museum