David Warsh: It may be too late but here’s a suggestion on saving print newspapers

Newspapers rolling off the press

— Photo by Knowtex

1896 ad for The Boston Globe

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It may have been pure coincidence that strains on American democracy increased dramatically in the three decades after the nation’s newspaper industry came face to face with digital revolution. Then again, the disorder of the former may have something to do with the latter.

Since 2001, the last good year, daily circulation of major metropolitan newspapers has been plummeting. An edifying survey last year found that The Wall Street Journal, at the top of the field, delivered more print copies daily (697,493) than its three next three competitors combined: The New York Times (329,781), USA Today (149,233) and The Washington Post (149,040).

All but one of the top 25 newspapers reported declining print circulation year-over-year. The Villages Daily Sun, founded in 1997 in central Florida, not far north of Orlando, was up 3 percent, at 49,183, ahead of the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Is there still a market for print newspapers? Maybe, maybe not. There is probably only one good way to answer the question. I’d like to suggest a simple experiment: compete on price.

The New York Times Company bought The Boston Globe 30 years ago this week for $1.13 billion, in the last days of the golden age of print journalism. The Times ousted the Globe’s fifth-generation family management in 1999, installed a new editor in 2001, and, for 10 years, rode with the rest of the industry over the digital waterfall.

The Globe, whose 2000 circulation had been roughly 530,000 daily and 810,000 Sunday, broke one great story on the way down. Its coverage of the systemic coverup of clerical sexual abuse of minors in the Roman Catholic Church beginning in 2002 has reverberated around the world. The story produced one more great newspaper movie as well – perhaps the last — Spotlight. Otherwise the New York Times Co. mismanaged the property at every opportunity, threatening at one point to simply close it down. It finally sold its New England media holdings in 2013 to commodities trader and Boston Red Sox owner John W. Henry for $70 million.

Since then, the paper has stabilized, editorially, at least, under the direction of Linda Pizzuti Henry, a Boston native with a background in real estate who married Henry in 2009. Veteran editor Brian McGrory served for a decade before returning to column writing this year. Nancy C. Barnes was hired from National Public Radio to replace him; editorial page editor James Dao arrived after 20 years at the Times. A sustained advertising campaign and new delivery trucks gave the impression the Globe was in Boston to stay.

Henry himself showed some publishing flair, starting and selling a digital Web site, Crux, with the idea of “taking the Catholic pulse,” then establishing Stat, a conspicuous digital site that covers the biotech and pharmaceutical industries. Henry’s sports properties – the Red Sox, Britain’s Liverpool Football Club, a controlling interest in the National Hockey League’s Pittsburgh Penguins, and a 40 percent interest in a NASCAR stock car racing team, are beyond my ken.

There is, however, one continuing problem. The privately owned Globe is thought to be borderline profitable, if at all. It seems to have followed the Times Co. strategy of premium pricing. Seven-day home delivery of The Times now costs $1305 a year. Doing without its Saturday and overblown Sunday editions brings the price down to $896 for five days a week. The year-round seven days a week home delivery price for The Globe is posted in the paper as $1,612, though few subscribers seem to pay more than $1200 a year, to judge from a casual survey.

In contrast, six-day home delivery of WSJ costs $720 a year. The American edition of the Financial Times, in some ways a superior paper, costs $560 six days a week, at least in Boston. It is hard to find information about home-delivery prices for The Washington Post, now owned by Amazon magnate Jeff Bezos. But $170 buys out-of-town readers a year’s worth of a highly readable daily edition.

So why doesn’t The Globe take a deep breath and cut home-delivery prices to an annual rate of $600 or so, to bring its seven-day value proposition in line with those of the six-day WSJ and the FT? The Globe trades heavily on legacy access to wire services of both The Times and The Post; it is not clear how this would fit into such a bargain with readers. Long-time advertising campaigns would be required to make the strategy work.

That would be taking a leaf from The Times’s long-ago playbook. In 1898, facing falling ad revenues amid malicious rumors that it was inflating its circulation figures, publisher Adolph Ochs, who had bought the daily less than three years before, cut without warning its price from two cents to a penny, to the astonishment of his principal New York competitors on quality, The Herald and The Tribune. He quickly gained in volume what he gave up for the moment in revenue, raised the price a year later, and never looked back. The move has been hailed ever since as “a stroke of genius.”

Would it work today? It might. If it did, it would constitute a proof of concept, an example for all those other formerly great metropolitan newspapers to consider in hopes of creating a standard for two-tier home-delivery pricing: one price for the national dailies; a second, slightly lower price for the less-ambitious home-town sheet.

It might force The Times to cut back on its Tiffany pricing strategy, to take advantage of once-again growing home-delivery networks, and get print circulation increasing again, after two decades of gloomy decline.

Even digital publisher of financial information Michael Bloomberg might be persuaded to put his first-rate news organization to work publishing a thin national newspaper, on the model of the FT. Print newspapers have a problem with pricing subscriptions to their print daily papers. It is time for industry standards committees to begin considering the prospects.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

“Newspaper readers, 1840,’’ by Josef Danhauser

Mining the ‘microworld’

From Korean-American artist Miyoung So’s show “Yet to Be Seen,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, June 14-July 16

The gallery says:

“Inspired by fungal formations,’’ the show “features delicately detailed sculptural works constructed from hand-made cold porcelain and recycled materials. The artist muses, ‘As I traversed old wooden bridges, walked down roads lined with trees, and passed by my neighbors' houses, {in her hometown of Newton, Mass.} I noticed something ubiquitous: lichens, fungi, slime mold, and moss.’ She began to observe these small yet fascinating organisms closely, adjusting the zoom on her phone camera to capture their minute details. The microworld proved to be a wellspring of inspiration for her work.’’

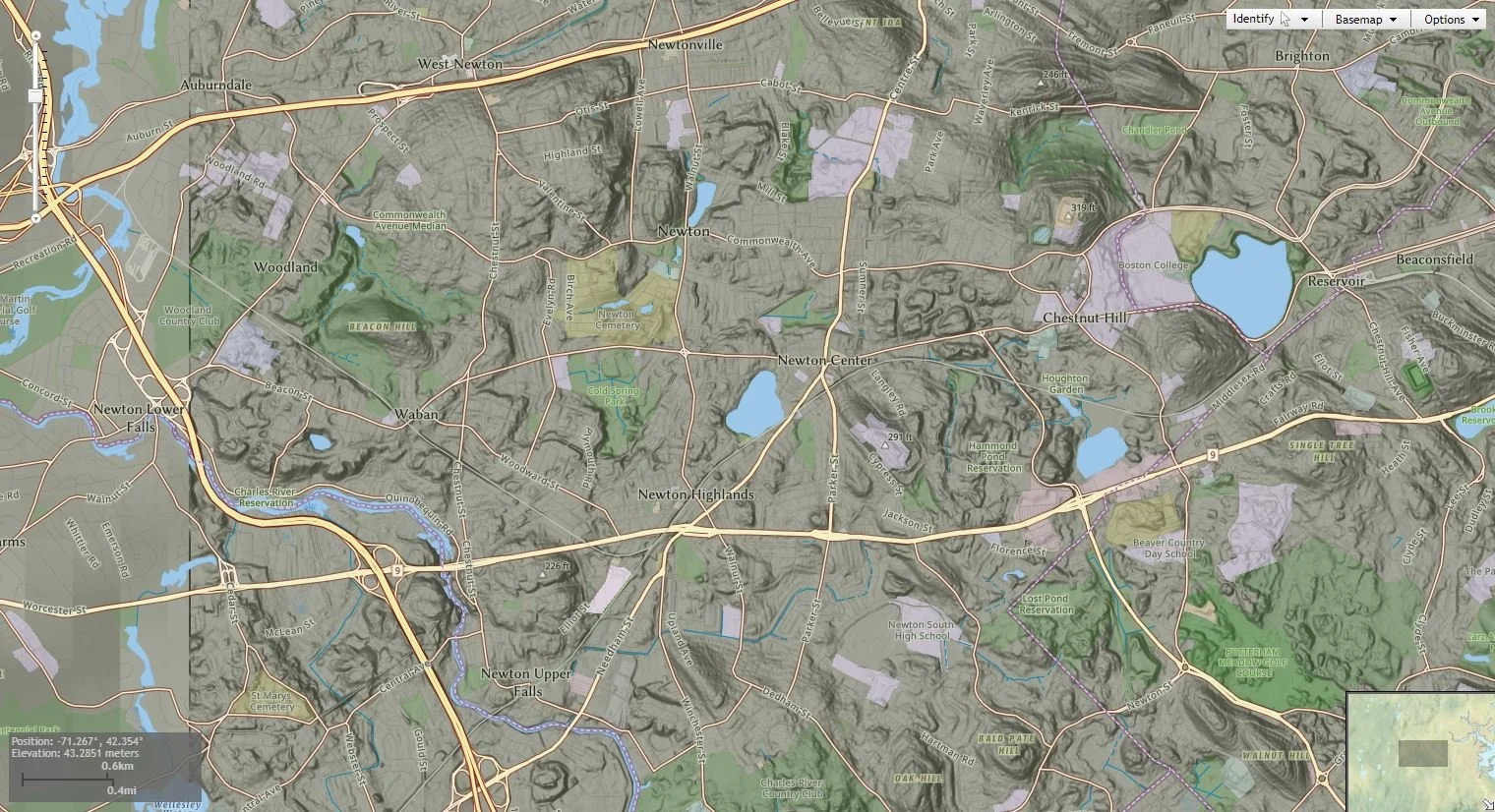

From a National Centers for Environmental Information elevation model of Newton terrain

#So Miyoung #Boston Sculptors Gallery

From a bay’s sea, sky, sand and rocks

“Rock 234: Yellow Flag” (painting), by Tom Gaines (1935-2023), in the show “Tom Gaines: The Last Paintings,’’ at Corey Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine. Mr. Gaines was based in New Jersey but also painted at his summer home, in Belfast, Maine.

He wrote:

“Since 2005, three major changes have taken place, which have brought me to where I am now… a series of more than 2,000 rock paintings.

“The first change came when I created, quite by accident, a different surface. I had attempted with mineral spirits to wipe out a color that I had allowed to dry for a few days. Some of the color remained, revealing layers of old and new color. This revelation of layers suggested erosion. I was so taken with the result that I purposely worked this way with subsequent paintings.

“The next change came while I was working on a series of interiors and decided to eliminate most of the subject matter. The result was a simpler, more geometric and more abstract composition. I worked this way for more than a year. Simplifying and layering.

“I made a third change while working in my studio in Belfast, Maine. I realized that I needed to prioritize my ideas regarding the relationship between subject matter and form. I found the simpler subject matter/composition from the sky, sea, sand, and rocks of Penobscot Bay.’’

#Corey Daniels Gallery #Tom Gaines

Penobscot Bay from Belfast

Blaisdell Residence, Belfast, from a circa 1920 postcard. It’s a Greek Revival mansion from the city's 19th Century shipbuilding boom. Known as The Williamson House (www.TheWilliamsonHouse.com) survives today as a Museum in The Streets landmark.

To promote ‘generous sentiments’

From the Constitution of Massachusetts, enacted in 1780:

“Wisdom and knowledge, as well as virtue, diffused generally among the body of the people, being necessary for the preservation of their rights and liberties; and as these depend on spreading the opportunities and advantages of education in the various parts of the country, and among the different orders of the people, it shall be the duty of legislatures and magistrates, in all future periods of this commonwealth, to cherish the interests of literature and the sciences, and all seminaries of them; especially the university at Cambridge {Harvard}, public schools and grammar schools in the towns; to encourage private societies and public institutions, rewards and immunities, for the promotion of agriculture, arts, sciences, commerce, trades, manufactures, and a natural history of the country; to countenance and inculcate the principles of humanity and general benevolence, public and private charity, industry and frugality, honesty and punctuality in their dealings; sincerity, good humor, and all social affections, and generous sentiments, among the people.’’

Green Mountain creepiness

From the “Haunted Vermont’’ show at the Bennington Museum, July 22-Dec. 31.

The Haunted Bridge, or Red Bridge, was a covered bridge that crossed the Walloomsack River just north of the Bennington Battle Monument. It was torn down around 1944. The caption for this postcard, c. 1920, reads: "The Haunted Bridge. On certain moonlight nights weird noises are said to have been heard in and around it. A phantom horseman is frequently heard clattering across and into a nearby farmyard."

The museum explains:

“Vermont has a long and storied history of otherworldly intrigue, ranging from accusations of witches in Pownal and vampires in Manchester, to Spiritualists communicating with the dead, haunted covered bridges, and our very own Bennington Triangle. Shirley Jackson, perhaps the greatest writer of the horror/gothic fiction genre in the 20th Century, lived and worked for most of her career in North Bennington. Drawing on this rich framework of historical tales of monsters, ghosts, missing persons and the occult, ‘Haunted Vermont’ will tell these stories and more.’’

Mixed messaging of vaccine skeptics sows seeds of doubt

An early 19th-Century satire of antivaxxers by Isaac Cruikshank

Headquarters, in Cambridge, Mass., of Moderna, one of the major COVID-19 vaccine makers

From Kaiser Family Foundation Health News

“It seems to me to be implying the government knows the vaccine to be unsafe” and that it’s “covering it up.’’

— Matt Motta, a political scientist at Boston University specializing in public health and vaccine politics

It was a late-spring House of Representatives hearing, where members of Congress and attendees hoped to learn lessons from the pandemic. Witness Marty Makary made a plea.

“I want to thank you for your attempts at civility,” Makary, a Johns Hopkins Medicine researcher and surgeon, said softly. Then his tone changed. His voice started to rise, blasting the “intellectual dishonesty” and “very bizarre” decisions of public health officials. Much later, he criticized the “cult” of his critics, some of whom “clap like seals” when certain studies are published. Some critics are “public health oligarchs,” he said.

Makary was a marquee witness for this meeting of the Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic. His testimony had the rhythm of a two-step — alternating between an extended hand and a harsh rhetorical slap. It’s a characteristic move of this panel, a Republican-led effort to review the response to the pandemic. Both sides of the aisle join in the dance, as members claim to seek cooperation and productive discussions before attacking their preferred coronavirus villains.

One target of the subcommittee’s Republican members has drawn concern from public health experts: COVID-19 vaccines. Because the attacks range from subtle to overt, there’s a fear all vaccines could end up as collateral damage.

During that May 11 hearing, Republican members repeatedly raised questions about coronavirus vaccines. Right-wing star Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R.-Ga.) emphasized the vaccines were “experimental” and fellow Georgia Republican Rep. Rich McCormick, an emergency room physician, argued the government was “pushing” Federal Drug Administration-approved boosters “with no evidence and possible real harm.”

Some Republican members, who have been investigating for months various pandemic-related matters, are keen to say they’re supportive of vaccines — just not many of the policies surrounding COVID vaccines. Rep. Brad Wenstrup (R.-Ohio), who chairs the subcommittee, has said he supports vaccines and claimed he’s worried about declining vaccination rates.

During the May hearing, he also two-stepped, arguing the COVID shots were “safe as we know it, to a certain point.” He questioned the government’s safety apparatus, including VAERS, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, a database that receives reports potentially connected to vaccines. He said the committee would be “looking” at it “to make sure it’s honest and to be trusted.”

It’s this two-step — at once proclaiming oneself in favor of vaccines, while validating concerns of vaccine-skeptical audiences — that has sparked worries of deeper vaccine hesitancy taking root.

“It seems to me to be implying the government knows the vaccine to be unsafe” and that it’s “covering it up,” said Matt Motta, a political scientist at Boston University specializing in public health and vaccine politics. The implication validates some long-held fringe theories about vaccinations, without completely embracing “conspiracism,” he said.

Vaccine skeptics run the gamut from individuals with scientific credentials who nevertheless oppose public health policies from a libertarian perspective to individuals endorsing theories about widespread adverse events, or arguing against the need for multiple shots. VAERS is a favorite topic among the latter group. When one witness testifying during the May 11 hearing attempted to defend covid vaccination policies, Taylor Greene cited the number of reports to VAERS as evidence of the vaccines’ lack of safety.

That muddles the purpose of the database, Motta said, which gathers unverified and verified reports alike. It’s a signal, not a diagnosis. “It’s more like a smoke alarm,” he said. “It goes off when there’s a fire. But it also goes off when you’ve left an omelet on the stove too long.”

In a March hearing focusing on school reopening policies, Democratic members of the panel and a witness from a school nurses association frequently touted the important role covid vaccines played in enabling schools to reopen. Wenstrup offered generalized skepticism. “I heard we were able to get more vaccines for the children,” he said. “We didn’t know fully if they needed it. A lot of data would show they don’t need to vaccinate.”

Witnesses can eagerly play into vaccine-skeptical narratives. After a question from Taylor Greene premised on the idea that the covid vaccines “are not vaccines at all,” and alleging the government is spreading misinformation about their effectiveness, Makary suggested that while he was not anti-vaccine, it was understandable others were. “I understand why they are angry,” he said, in response. “They’ve been lied to,” he said, before criticizing evidence standards for the newest covid boosters, tailored to combat emerging variants.

The signals aren’t lost on audiences. The subcommittee has, like most congressional panels, posted important moments from its hearings to Twitter. Anti-vaccine activists and other public health skeptics reply frequently.

“It’s hard for me to think of a historical analogue for this — it’s not often that we have a Congressional committee producing content that has its fingers on the pulse of the anti-vaccine community,” Motta wrote in an e-mail, after reviewing many of the subcommittee’s tweets. “The committee isn’t expressly endorsing anti-vaccine positions, beyond opposition to vaccine mandates; but I think it’s quite possible that anti-vaccine activists take this information and run with it.”

Motta’s concern is echoed by the panel’s Democratic members. “I pray this hearing does not add to vaccine hesitancy,” said Rep. Kweisi Mfume (D.-Md.), who represents Baltimore.

One witness reiterated that point. Many members “have a lot of skepticism about vaccines and were not afraid to express that,” Tina Tan, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases at Northwestern University, told KFF Health News. She testified at the hearing on behalf of the minority.

Polling is showing a substantial — and politically driven — level of vaccine skepticism that reaches beyond covid. A slim minority of the country is up to date on vaccinations against the coronavirus, including the bivalent booster. And the share of kindergartners receiving the usual round of required vaccines — the measles, mumps, and rubella, or MMR, inoculation; tetanus; and chickenpox among them — dropped in the 2021-22 school year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Support for leaving vaccination choices to parents, not as school requirements, has risen by 12 percentage points since just before the pandemic, mostly due to a drop among Republicans, according to a recent poll by the Pew Research Center.

And vaccine skepticism is resonating beyond the halls of Congress. Some state governments are considering measures to roll back vaccine mandates for children. As part of a May 18 procedural opinion, Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch cited two vaccination mandates — one in the workplace, and one for service members — and wrote that Americans “may have experienced the greatest intrusions on civil liberties in the peacetime history of this country.” He made this assertion even though American military personnel have routinely been required to get shots for a host of diseases.

“We can’t get to a spot where we’re implicitly or explicitly sowing distrust of vaccines,” cautioned California Rep. Raul Ruiz, the Democratic ranking member of the coronavirus subcommittee.

Darius Tahir is a Kaiser Family Foundation Health News reporter.

DariusT@kff.org, @dariustahir

‘Insistent materiality’

Work by the Modernist artist Elie Nadelman (1882-1946, American, born in Poland) in the show “Material Matters,’’ at the Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Conn., through Sept. 24.

The museum says:

“Nadelman is best known for his sculptural explorations of pure form. Melding classical source material and folk art, Nadelman’s sculptures range from idealized heads and animals to genre subjects drawn from everyday life, such as acrobats, circus performers, and dancers.

“Featuring more than twenty sculptures, this show showcases the artist’s experimentation with materials. In the early 1910s, he created idealized, classical heads in conventional materials such as bronze, marble, and stone. He expanded his practice by the end of the decade to include wood and plaster figural sculptures inspired by his experience of living in New York City. From the 1920s until the end of his career, Nadelman increasingly gravitated toward inexpensive, nontraditional materials. … The painted, textured, and weathered surfaces of Nadelman’s sculptures—their insistent materiality—are part and parcel of Nadelman’s modernity.’’

Llewellyn King: Smoke spreads amidst global warming but beware overzealous regulation

Smoke from Canadian forest fires in the Delaware River Valley. See New England’s “Dark Day’’.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The smoke from wildfires in Canada that has been blown down to the United States, choking New York City and Philadelphia with their worst air quality in history and blanketing much of the East Coast and the Midwest, may be a harbinger for a long, hot, difficult summer across America.

It could easily be the summer when the environmental crisis, so easily dismissed as a preoccupation of “woke’’ Greens and the Biden administration, moves to center stage. It could be when America, in a sense, takes fright. When we realize that global warming is not a will-or-won’t-it-happen issue like Y2K at the turn of the century.

Instead, it is here and now, and it will almost immediately start dictating living and working patterns.

In an extraordinary move, Arizona has limited the growth in some subdivisions in Phoenix. The problem: not enough water. Not just now but going forward.

The floods and the refreshing of surface impoundments, such as Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the nation’s largest reservoirs, haven’t solved the crisis.

All along the flow of the Colorado River, aquifers remain seriously depleted. One good, rainy season, one good snowpack may recharge a dam, but it doesn’t replenish the aquifers that hydrologists say have been undergoing systematic depletion for years.

An aquifer isn’t just an underground river that runs normally after rainfall. It takes years to recharge these great groundwater systems. These have been paying the price of overuse for years; across Texas and all the way to the Imperial Valley, in California, unseen damage has been done.

It isn’t just water that looms as a crisis for much of the nation, there is also the sheer unpredictably of the weather.

I talk regularly with electric- and gas-utility company executives. When I ask them what keeps them awake at night, they used to respond, “Cybersecurity.” Recently, they have said, “The weather.”

This year, we are entering the tropical-storm season with unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Atlantic and the Pacific. The doleful conclusion is that these will signal severe and very damaging weather activity across the country.

The utilities have been hardening their systems, but electricity is uniquely affected by weather. The dangers for the electricity industry are multiple and all affect their customers. Too much heat and the air-conditioning load gets too high. Too much wind and power lines come down. Too much rain and substations flood, poles snap and there is crisis, from a neighborhood to a region.

In the electricity world, the words of John Donne, the 16th-Century English metaphysical poet, apply, “No man is an island entire of itself.”

There is another threat that the electricity-supply system will face this summer if the weather is chaotic: overzealous politics and regulation.

It is the electric utilities that are most identified in the public mind with climate change. The public discounts the myriad industrial processes as well as the cars, trucks, bulldozers, trains and ships that lead to the discharge of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Instead, it is utilities that have a target pinned to them.

A bad summer will lead to bad regulatory and bad political decisions regarding utilities.

Foremost are likely to be new attacks on natural gas and its supply chain, from the well, through the pipes, into the compressed storage, and ultimately to combustion turbines.

At this time, natural gas – about 60-percent cleaner than coal — is vital to keeping the lights on and the nation running when the wind isn’t blowing, or the sun has set or is obscured.

The energy crisis that broke out in the fall of 1973, and lasted pretty well to the mid-1980s, was characterized by silly over-reactions. First among these was probably the Fuel Use Act of 1978, which got rid of pitot lights on gas stoves and even threatened the eternal flame at Arlington Cemetery.

It also accelerated the flight to coal because, extraordinarily, that was the time of the greatest opposition to nuclear power — from the environmental communities.

This summer may be a wakeup for climate change and how we husband our resources. But wild overreaction won’t quiet the weather.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and a long-time editor, writer and consultant in the international energy sector. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

#global warming #Llewellyn King #electric utilities

Animal rights and abuses in New Bedford show

“Massachusetts State of the Union,’’ by Providence/West Palm Beach artist Jane O’Hara, in the show of the same name at the New Bedford Art Museum, through Aug. 20

— Photo courtesy New Bedford Art Museum.

The museum explains that the show looks at animal rights and the complex relationship between humans and other animals. “Covering the 50 states of the union, O'Hara's work examines animal rights abuses through the lens of classic ‘wish-you-were-here postcards.’’’

#Jane O’Hara #New Bedford Art Museum

Going Dutch

Downtown Boston

— Photo by Nick Allen

Adapted from From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

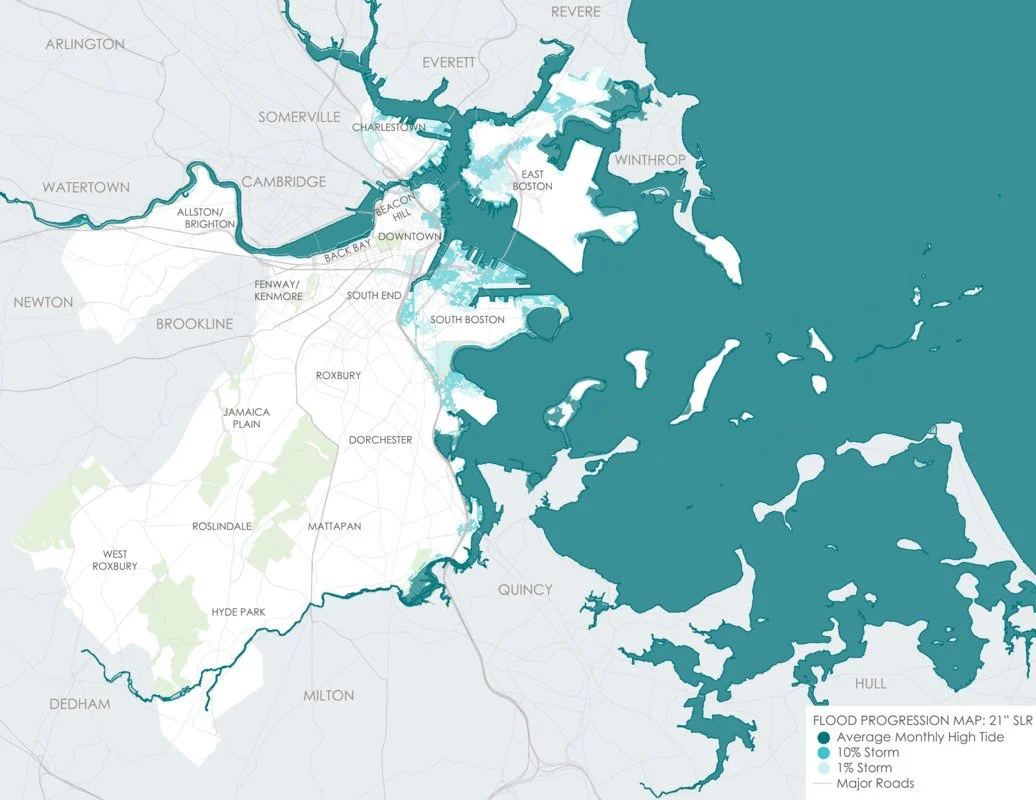

A consulting firm’s study recommends that a huge, $877 million flood barrier be built to protect downtown Boston from the increased coastal flooding associated with global warming. Of course, there would be big cost overruns in something as complicated as this project; it would probably cost several billion.

Meanwhile, Boston can stock up on lifeboats, wetsuits and swimming lessons. But sadly the threat is too episodic for gondolas.

John Sideli and ‘the strange liberty of creation’

John Sideli with some of his creations

VERNON, Conn.

The ancient Greeks have a saying: “To meet a friend again after a long absence is a god.”

My wife, Andrée, and I have known John Sideli for more than 60 years. After a long absence, we met again in Bristol, R.I., where, close by in Warren, Andrée and I enjoyed a brief vacation. As the word “vacation” suggests, times spent in this way together are best savored without all the modern inconveniences: no computers, no phones, and, in my case, no newspapers -- seven days, a full week, of serendipity, and a welcomed respite from the drudgery of column writing.

Andrée has always said that political writing is a bit like scrawling a message with your finger on a strand of tide-hardened beach before the tide rushes in to erase it.

On day three, she smiled mischievously and said, “I’ve arranged a surprise for you. I’m sure you will be pleased. I can’t tell you what the surprise is, because then it will be no surprise.” There were no flaws in this logical construction.

The surprise was John Sideli, changed somewhat from the Sideli I knew six decades earlier and now living in Bristol. But the point of the Greek saying is that memories, sleeping in the brain for years, are always youthful. They stir and come to life when, after a long absence, we meet an old friend again.

Sideli’s first love was antiques, and he had a jeweler’s eye for beauty, always an enticing mistress. He was a purveyor of cluttered antique shops, junk yards and astonishing roadside finds. The eye that pierces through facades and strikes at the bone and muscle of things, destructs and constructs anew. And if it is an artist’s eye, the new construction carries within it the essence of things. All art is a reconstruction of buried narratives brought to life again by the work of the artist.

There is in Sideli’s works a living drama, the result of separate pieces of time cunningly brought together in a frame. Quite like characters in a play, these essences, alive and jostling each other, produce in a viewer pity, sorrow, laughter, tears, all the ragged radiations of a drama. They tell, they speak to the viewer. And what the viewer carries away from the encounters depends, ultimately, on what he or she brings to them.

In 1968, Sideli found himself caretaking for two years at the Roxbury, Conn., estate of the very much in demand and famous sculptor Alexander Calder, noted for his stabiles and mobiles. The experience was transformative. In some of his pieces, Calder had been collecting and putting together – deliberatively and artfully, not randomly – certain found objects that had appealed to his aesthetic sensibilities. Calder at play, it turned out, had a very well developed sense of humor present in many of his pieces. During a visit to the estate, I remember in particular a playful tabletop carousel, art and humor shaking hands and greeting each other as old friends.,

At the same time, Sideli had been collecting various bits and pieces that had appealed to him. “I realized,” Sideli noted in a Hirschi & Adler showing in New York in 2013, “why I had been collecting these fragments, bits and oddities. I was amazed by the way they would take on a new meaning when juxtaposed in different contexts. They would acquire a kind of narrative aspect and even evoke a sacred mood in a very short time. I became a champion of the art of everyday objects.”

We were seated in Sideli’s modest living room, surrounded and captivated by his enticing “mixed media constructions.” That verbal construction belongs to Riviére, at Robert Young Antiques of Battersea Bridge Road, London, an antique dealer that featured Sideli some years ago.

He was showing me some photos, some of which he had sold at mouthwatering prices to all and sundry -- millionaires, workmen, professionals of every stripe, including butchers, bakers and, for all I know, candlestick makers.

Two people had come into his then-shop in Wiscasset, Maine, looked around a bit, and the female almost immediately pointed to a humorous rendition and said, “That’s it. That’s the one I want.”

Such decisions are easily made because it is impossible not to have a conversation with the Sideli piece you love, and many purchases are the result of love at first sight. Recently, Sideli asked his daughter – trying his best to be uncomplicated -- which of the pieces she would like after he had gone the way of all flesh.

Answer: “All of them.”

“The color in this one,’’ I said, “is farm tractor red.”

“That is because the metal plate [featured in the piece] came from a tractor, or part of a roof, painted tractor red, that housed the tractor in an out-of-the way place in Costa Rica.”

Naturally, a narrative attached to the art work.

The farmer from whom Sideli had procured the plate was irascible, with a short temper, not unusual in intensely practical farmers everywhere. Farmers want to be about their business. Intrusions not business related tend to be costly. The man was cocking a poisonous eye at Sideli, who had, very politely, asked the farmer whether he might be willing to carve out a piece of his farm equipment for an art project. The price was right, the thing was done, and I was now staring at the final product.

Most of Sideliworks are tinted with humor, as are most of the conversations I’ve had with Sideli. That is because humor is always the result of a joyful asymmetry, an incongruous mixing of tragedy and comedy, a disproportion that strikes the fancy immediately, the way a hammer strikes the gong.

“That’s the one I want.”

Years after Sideli had returned to America from Costa Rica, where he had been living for a few joyous years, he returned to the farm, surprised to see the old farmer was still among the living.

“I doubt you remember me,” Sideli said to the farmer.

Some people, and some circumstances, are unforgettable.

“Oh, I remember you alright.”

Strolling the streets of Costa Rica, Sideli was struck by the various colors of metal street plates, all of them softened by years of sun and rough weather but, like distant stars, still shining brightly.

“I went in search of some cast off plates and found a shop that replaced them.”

He said to the owner of the shop, “I’d like to buy those used plates.”

Big smile! Here was an American with money.

“I have some new plates right over here.”

“No, no. I don’t want the new plates. I want these old plates, no others. How much?”

The two arrived at a price, and Sideli carried off the used plates as if they had been venerable religious objects.

French author and philosopher Albert Camus lived his life – much too brief, as it turned out -- with his eyes wide open. We tend to forget that all art is a transcendent product of time and space. “To create today,” Camus tells us, “is to create dangerously… The question, for all those who cannot live without art and what it signifies, is merely to find out how, among the police forces of so many ideologies… the strange liberty of creation is possible.”

“Protect the Innocent’’

The construction of “Protect the Innocent” began with a news account of a horrific rape in South America, Shortly after the account appeared, Sideli noticed two white, truncated mannequins lying in mud, discarded on the roadside. He washed them carefully and brought them home. The viewer will notice the saw-toothed metal rim of the frame. The mannequins, draped in tassels, are immaculate but vulnerable and white as a communion wafer.

In an artist’s note Sideli writes, “I assemble and arrange objects in the same way that a poet chooses words. I try to carefully combine them in a way that allows them to transcend their original form or purpose and evoke a feeling or tell a story. And as with poetry, there is a certain rightness to a particular combination or arrangement that will express with directness and simplicity what I want to say.

“I believe that there is spirit in matter, which, if tapped, can have a powerful resonance when objects are carefully tuned, coaxed, combined and juxtaposed.”

The sensuous penetration of all art depends ultimately upon the presence of the artist in the work and the attention viewers or auditors bring to it.

Those lucky enough to own a Sideli art work will find they need never be alone. Sideliworks, like the remembered poem, stay with you, a faithful companion, when everyone else has left the room.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

#John Sideli #Don Pesci

Studying New England birds’ perilous migrations

Male (left) and female (right) American goldfinches at a thistle feeder. The American goldfinch can be found in Rhode Island year-round, though some individuals migrate south during the non-breeding season.

From an article by Bonnie Phillips in ecoRI News:

“Scientists and biologists know much more about bird migration now, why they do it and, for the most part, how. Almost half of all birds migrate in some form or another. Many migrate at night, when the weather is calmer and there are fewer predators. Some birds travel as far as 7,000 miles nonstop, and others return to the same locations year after year.

“Migration takes a toll on birds — it’s a dangerous time, when the exhausted birds are especially vulnerable to predators, deteriorating habitat, and climate change. Researchers are realizing that it’s vital to understand migration patterns and habitat usage to prevent further loss of already declining bird populations.

“‘The more bird migration comes into focus, the more we realize that, to conserve our declining birds, we must focus our attention on these strenuous and perilous periods in their lives,’ said Charles Clarkson, director of avian research at the Audubon Society of Rhode Island.

“The society’s recently released State of Our Birds Part II report is a start toward examining the habits of birds that use Audubon’s 9,500 acres of refuges as stopovers on their migrations. Research suggests Rhode Island — the {rural/exurban} western part of the state in particular — is more important than any other New England location for migrating birds.’’

To read the full article, please hit this link.

#birds #Rhode Island

Family history and beyond

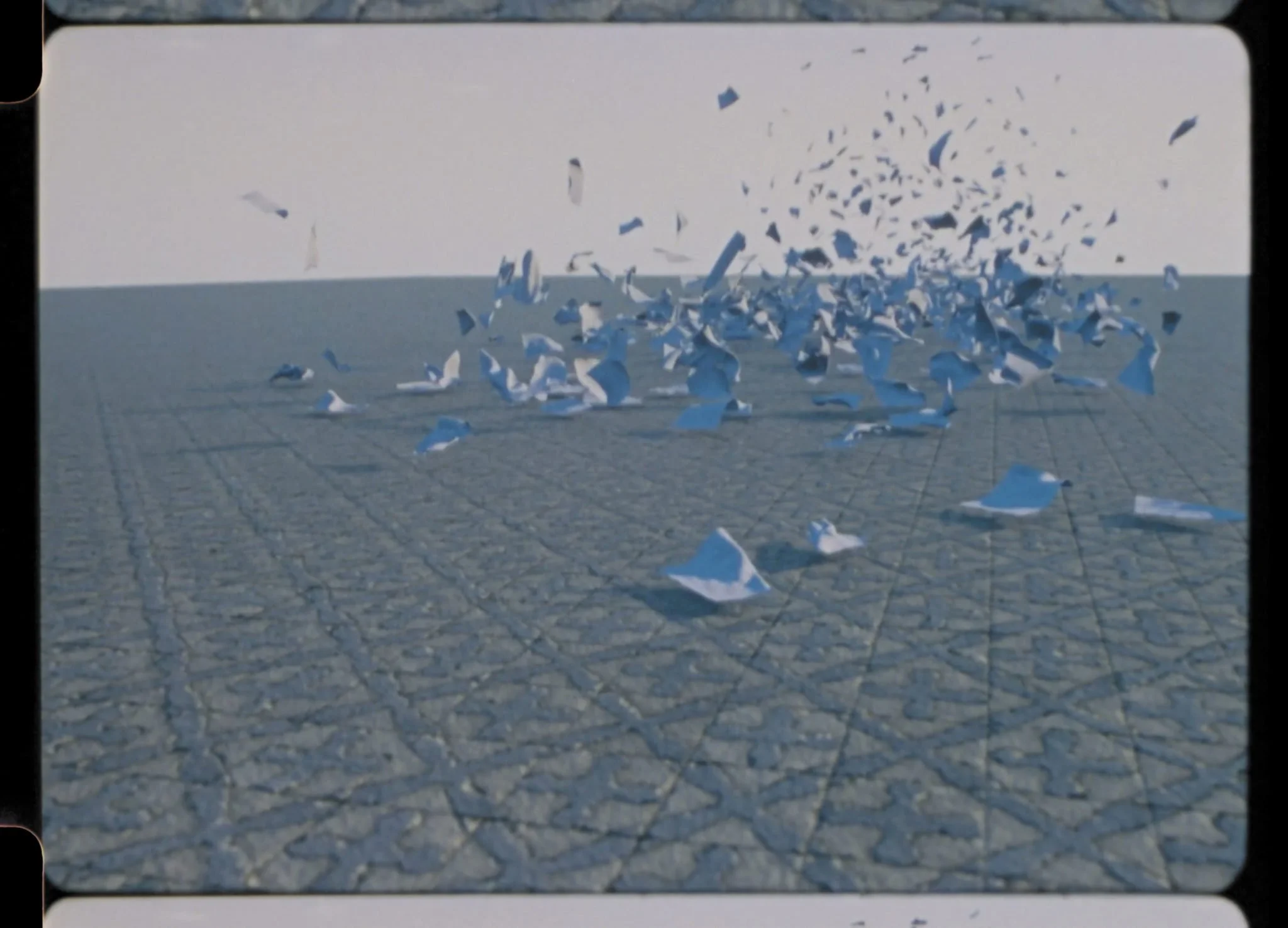

In Suneil Sanzgiri’s show “To See Oneself at a Distance,’’ at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, North Adams, Mass., through next April.

The museum explains:

“In a trilogy of short films shown in a new installation, Suneil Sanzgiri probes the intersection between his family’s history in Goa, India, and stories of global solidarity, freedom fighters and neocolonial extractive forces.’’

# Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art

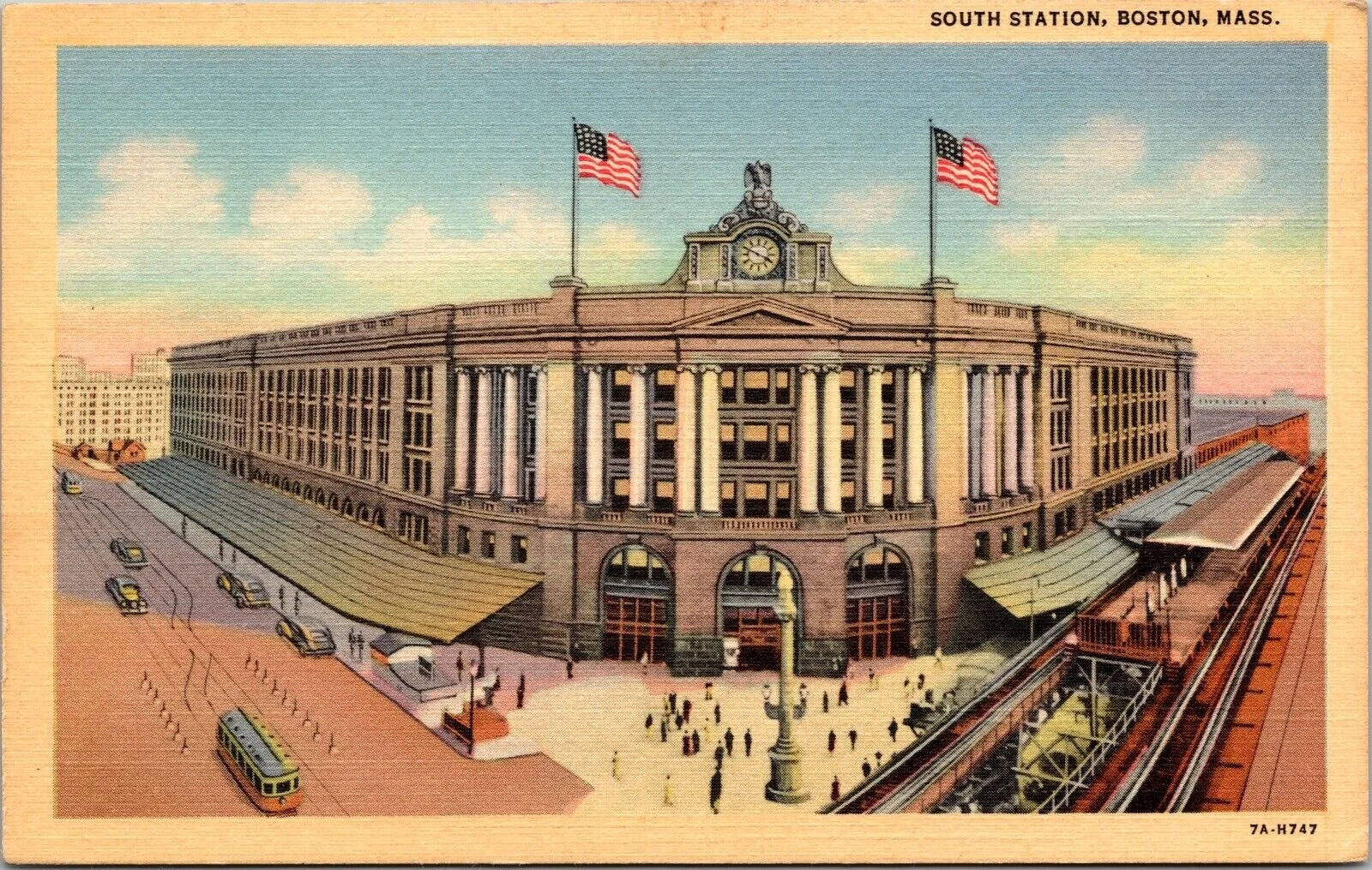

Boston bummer

Boston’s South Station in the Thirties

“I have just returned from Boston. It’s the only sane thing to do if you find yourself up there.’’

xxx

“There was a rumor that {Boston} Mayor {John F.} Fitzgerald {maternal grandfather of President John F. Kennedy} had sung ‘Sweet Adeline’ in office for so many years that the City Hall acoustics had diabetes.’’

— Fred Allen (whose birth name was John Florence Sullivan) (1894-1956), in a June 1953 letter to Groucho Marx (1890-1977). Allen was raised in Boston and became a star comedian of “The Golden Age of Radio’’.

#Fred Allen

#Boston

Two summers

“Flaming June’’ (1895), by Lord Leighton (1830-1896)

There is a June when Corn is cut

And Roses in the Seed—

A Summer briefer than the first

But tenderer indeed

As should a Face supposed the Grave's

Emerge a single Noon

In the Vermilion that it wore

Affect us, and return—

Two Seasons, it is said, exist—

The Summer of the Just,

And this of Ours, diversified

With Prospect, and with Frost—

May not our Second with its First

So infinite compare

That We but recollect the one

The other to prefer?

— Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), lifelong resident of Amherst, Mass.

Rise and fall

“Fallen Tree and Wetland’’ (oil on canvas), by Provincetown artist Donald Beal, in the show, “Sky Power,’’ with Paul Bowen, at Berta Walker Gallery, Provincetown, June 16-July 9

The gallery says:

"Donald Beal's work breaks new ground in a gentle but inviting manner; his use of color and light are only devices designed to accent his unique sense of observation. What sets Beal's expression apart from those of his predecessors, however, is the lens from which he gazes. His perspective of nature is, in a sobering yet enlightening style, reflective of himself."

#Berta Walker Gallery

#Donald Beal

Being adaptable

“If you've worn shorts and a parka at the same time, you live in New England.’’

“If you have switched from 'heat' to 'A/C' in the same day and back again, you live in New England .”

—Jeff Foxworthy (born 1958), American actor, author, comedian, producer and writer. He grew up in Georgia.

Heat pumps are particularly effective in places with wildly variable temperatures such as New England.

Very old-fashioned

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

We attended part of Yale University’s commencement on May 22, at the School of Music, where a young friend of ours was getting a doctorate. We were struck again by how these ceremonies are some of the few remaining events connecting us to Medieval and Renaissance times – the robes draped with various university’s colors, the floppy velvet caps, the smattering of Latin, not to mention Yale’s famous Gothic Collegiate architecture, constructed with early 20th Century industrial/robber baron money and made to look very old – recalling Oxford and Cambridge and befitting an institution aimed at nurturing America’s Anglophilic ruling class.

But some of the degree recipients’ sandals and tattoos were reminders of where we are now.

Commencement speakers, both officials from the university or college itself as well as speakers from outside, affect an old-fashioned earnestness, if seasoned with successful or failed stabs at mild humor. Irony is heavily rationed at these things. It conveys a kind of theatrical innocence.

All students admitted to the Yale Music School go tuition-free, with the exception of those who have earned equivalent funding from other sources, thanks to a gift from an alumnus mogul called Stephen Adams. The marriage of big money and art. The Medicis, the leading bankers and art patrons of Renaissance Florence, would have approved.

Don’t try this in Florida

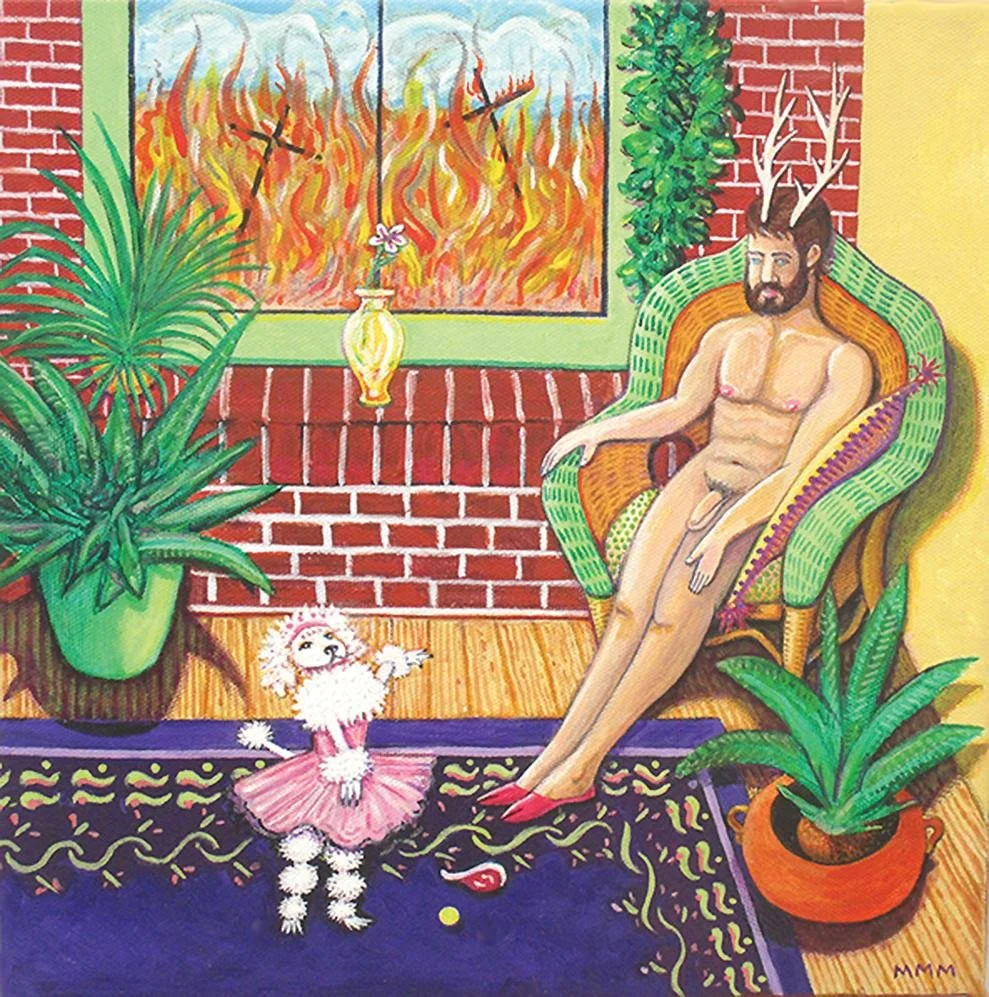

“At Home with the Devil (acrylic on canvas), by Marshall Moyer, in his show “Inappropriate,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through July 2

The gallery says:

“Moyer’s representational art explores situations, both real and imagined, evoking strong emotional responses that serve as social commentary.’’

The artist says:

"Ultimately, it is my job to give you something new to see. Even a negative response, if visceral and raw, is considered a victory. I behold the world around me with a dark and cynical wit, like a battered subway car careening through the 21st century with faulty brakes. All I ask is a view through a window not clouded, smudged or streaked with fingerprints, and I hope I can still be amazed through eyes wide open.’’

#Marshall Moyer

#Galatea Fine Art

Where he wanted to be

The Connecticut River depositing silt as it enters Long Island Sound at Old Lyme

“I have seen rather more of the world’s surface than most men ever do, and I have chosen the valley of this river for my home.’’

—Roger Tory Peterson (1908-1996), in The Connecticut River, by Evan Hill (1972).

Peterson was a famed ornithologist and naturalist and author of best-selling wildlife guides. He lived in Old Lyme, Conn.

#Connecticut River