The thing is to focus on the shimmer

“One Thing’’ (water-based paints and acrylic matte media on stretched canvas), by Renee Khatami, in the big group show “Abstract Visions,’’ at the Silvermine Arts Center, New Canaan, Conn., through April 20.

The name "Silvermine" comes from old legends of a silver mine in the area, although no silver has ever been found. The Silvermine area was long an arts colony.

Silvermine Tavern and mill pond.

April angst

“The sun was warm but the wind was chill.

You know how it is with an April day

When the sun is out and the wind is still,

You’re one month on in the middle of May.

But if you so much as dare to speak,

A cloud comes over the sunlit arch,

A wind comes off a frozen peak,

And you’re two months back in the middle of March.’’

— From “Two Tramps in Mud Time,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Old books, old industries

“The Bookworm’’ by Carl Spitzweg (1850)

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

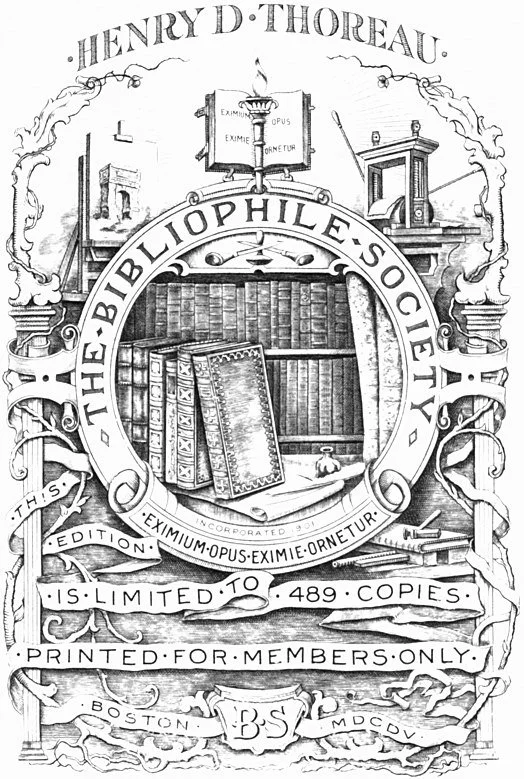

I was a guest the other week of a group of bibliophiles in Boston. Members’ passion for (mostly old) books, for their physical charms as well as their content, was endearing, as was the droll humor of some of the members I talked with.

At each of these dinner meetings, a member gives a talk. The speaker when I was there discussed a narrative about a Pacific island covered with guano, which for part of the 19th Century was used to make a highly profitable product in New England. Yankee businessmen would ship the stuff from the Pacific or the Caribbean, mix it with fish meal and market it as the best fertilizer, which it was until manmade ones came along (to eventually pose serious environmental problems). Some of my ancestors were investors in the Pacific Guano Co., in Woods Hole, on Cape Cod. (“Whitcomb, I always knew you were full of….”). The company occupied land where you now get the ferries to Martha’s Vineyard.

Pacific Guano Works, Woods Hole, Mass., circa 1860s; engraving by S.S. Kilburn. Woods Hole is a village in Falmouth.

Most industries eventually shrink or even disappear. In New England, the best examples are the shoe and textile sectors. (No comment on the slave trade or “The China Trade,’’ some of which involved selling opium.) So always diversify! Mix it up!

I thought of that while reading a Commonwealth Magazine article about Greater Boston losing manufacturing jobs and industrial land at an alarming pace. This needs to be reversed. We need more than white-collar jobs. And having local factories can help reduce supply-chain costs.

The article noted:

“A deteriorating regional industrial base has the potential to damage our region’s economic strength, pricing smaller companies out of the area and disproportionately impacting workers of color and those without college degrees. Economic studies tie healthy manufacturing employment and ecosystems to greater economic resilience and innovation, and the revitalization of American industry is key to building a middle class and addressing wage disparities. And yet, we are already facing a large-scale loss of space that could impact our state for many generations.’’

The region’s bio-tech biz has shown great growth in the past couple of decades, but it’s dangerous to depend on one sector. Just ask the folks in Silicon Valley.

Into a confusing new century

A great show, even for nonhistory buffs.

The tenth annual Decades Ball takes up the years 1900 to 1910. The evening features renowned actors and musicians performing signature works from the decade—and celebrates the 15th anniversary of Lapham’s Quarterly.

John S. Long: On a chilly beach, I see my first ospreys of 2023

An osprey, a great fish eater

I walked along Gaspee Point,* in Warwick, R.I., late this morning. The ospreys, in my first sighting this year, are back, and they are rebuilding their platform nest. It looked as if the male was bringing some small branches, clasped in his talons, toward the nest (perched high on a telephone pole). He hovered in the northwest wind and then dropped down onto the nesting platform.

I walked to Occupessatuxet Cove, toward the nearly submerged Greene Island, which was 14 acres before the 1938 Hurricane. Now, it’s almost gone. The chilly wind was about 15 mph, and the bay was shimmering gold as cat's paws swept across its surface. I could see Mt. Hope Bridge, connecting Bristol and Portsmouth, about 10 miles to the southeast. There seemed to be no marine traffic today as fluffy clouds drifted toward Bristol and Middletown. There's a 270-degree view from the High Banks at Gaspee Point. I gazed at the shades of ultramarine and indigo that uncoiled toward the shipping channel.

*A concave beach perhaps a mile long from north to south on the west side of Narragansett Bay; it’s famous for the burning of the burning of the HMS Gaspee, in 1772. For readers not familiar with Narragansett Bay, the point is bounded on the north by Passeonkquis Cove and on the south by Occupessatuxet Cove, and it’s reached via Namquid Drive in Warwick.

On Gaspee Point

‘Vehicle for self-knowledge’

“I think you are the bravest person I know, in that I can't predict” (hand-cut paper), by Antonius Bui, in the show “New Explorations in Mediascapes and Memoryscapes, at the Bannister Gallery, Providence, through April 21.

— Photo courtesy Bannister Gallery

The gallery explains that the show presents the work of Karen Azoulay, Antonius Bui, Natalia Nakazawa, Sagarika Sundaram, Yelaine Rodriguez and Ayoung Yu as they "interpret their personal histories" through a wide array of mixed media. Through this diverse collection of works, these artists explore "human perception and connection as a vehicle for self-knowledge."

Chris Powell: If sex changes become routine, America will get even crazier

MANCHESTER, Conn.

According to an assistant secretary of the U.S. Health and Human Services Department, Rachel Levine, who spoke the other day at the Connecticut Children's Medical Center, in Hartford, "gender-affirming care" -- the euphemism for sex-change therapy -- will be common and considered normal before too long.

Levine may be right but no one should hope so.

For it would signify profound national unhappiness if many people were so uncomfortable in their own skin that they would want to undergo physique-altering drug treatments and even mutilation. The law should prohibit this kind of thing for minors, for the same reason that it prohibits minors from making contracts and should prohibit minors from marrying, as is increasingly being urged. Minors aren't prepared to make such decisions.

Children may grow out of gender dysphoria, as they grow out of many other things, and evidence that sex-change therapy increases the long-term happiness of those who undertake it is lacking, even as the therapy may have irreversible effects.

While it does not seem to have been noted, the rise in gender dysphoria among children corresponds with the explosion of mental illness generally among the young. This may not be a coincidence.

After all, about a third of children in the United States live in a home without two parents and thus with less parenting and support than most children used to get. Many of those children are living in poverty. In cities the percentage of children living in poverty without fathers approaches 90 percent.

Meanwhile, school performance is crashing throughout the country.

The explosion in youthful mental illness (and mental illness in the adult population as well) would seem to invite government to inquire urgently into its cause.

Indeed, the mental illness epidemic may be more damaging than the recent virus epidemic was. But no.

Instead Assistant Secretary Levine remarked in Hartford that sex-change therapy for minors has the "highest support" of the Biden administration.

If such an administration remains in power, the assistant secretary's prophecy that sex-change therapy for children will become normal could be self-fulfilling, whether such therapy is really needed or not and though the country won't be any saner for it.

xxx

MORE URGENT THAN BONUSES: While state government has begun paying $45 million in bonuses to 36,000 of its "essential" employees, a couple of sad news reports related to government finance were largely overlooked.

The housing authority in Bridgeport is evicting about a fifth of its households, 502 of 2,500, because they haven't been paying rent and are already about $1.5 million in arrears. In New Haven a longstanding camp of homeless people in a city park, considered a sanitation and fire hazard, was dismantled and bulldozed by city employees.

The city governments didn't mean to be cruel. They are striving to find other accommodations for the people being displaced, some of whom of course have drug and other mental problems. Even so, people living in a homeless camp are probably not in a condition to support themselves, just as people who can't cover the rent in government housing for the poor probably aren't either.

That doesn't mean that with some temporary support, rehabilitation, and training these people couldn't support themselves eventually, but their present is desperate. They need shelter immediately, and in Connecticut shelter is scarcer and more expensive than ever.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont is not indifferent to the problem. His administration has just given $2.45 million to Pacific House, a social-service organization that operates emergency shelters, to build 39 inexpensive apartments to become "supportive housing" in Stamford. But as the evictions in Bridgeport and New Haven show, that housing will not be nearly enough for immediate needs.

So Connecticut should consider opening a few emergency shelters such as the field hospitals the National Guard set up quickly during the COVID pandemic. Much vacant retail, school and church property might be adapted for this purpose. Of course, supervisory staff would have to be hired, and rules devised and enforced to keep the facilities clean and orderly, but such a project would not be complicated, except maybe for assuaging the neighbors.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)\

Plants as metaphor

“Journey “ (Japanese barberry) (detail work in process), by Boston-based artist Ann Wessmann, in her show “Cycle,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, May 31-July 2.

The gallery says (this has been edited):

“In her studio practice, Ann Wessmann explores themes relating to time, memory, beauty and the ephemeral, with a focus on the strength and fragility of human beings and the natural world. Her most recent work pays tribute to trees, and the natural world by extension, by focusing on a horse chestnut tree at her childhood home, in Scituate, Mass., and the 170-foot-long hedge on two sides of the yard. This tree and hedge have been a part of her life for almost 70 years, going through their cycle of life as Wessmann goes through hers. While Wessmann no longer lives full time at her childhood home, she takes care of the yard year after year in the continuing seasonal cycle.

“Wessmann’s process is close observation and discovery, gathering and sorting various plant materials — leaves, flowers, twigs, nuts and hulls — that fall to the ground from the horse chestnut tree. These materials are essential to the life of the tree, but they have served their natural purpose and are generally overlooked and discarded by humans. Wessmann finds them beautiful and compelling. The thorny hedge, which she has struggled to maintain for many years, caught her attention in the past year, and the installation “Journey,’’ made with hedge clippings, for Wessmann became a metaphor for the times in which we live.”

Leaves and trunk of a horse chestnut tree. There are far fewer such trees these days.

— Photo by Alvesgaspar

The fruit of the Horse chestnut tree. They are not true nuts, but rather capsules.

— Photo by Solipsist

Free time for drinking

Franklin Pierce

“Frequently the more trifling the subject, the more animated and protracted the discussion.’’

xxx

“After the White House what is there to do but drink?’’

Franklin Pierce (1804-1869), the 14th president (1853-1857), who historians generally consider one of the worst. He was the only president to hail from New Hampshire. He grew up in Hillsboro and died in Concord, of alcoholism.

Pierce was a Northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity, and he alienated anti-slavery groups by signing the Kansas–Nebraska Act and enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act.

The Franklin Pierce Homestead, in Hillsboro, N.H., where Pierce grew up, is now a National Historic Landmark. He was born in a nearby log cabin as the homestead was being completed.

Odd that even a New Hampshire college would name itself after Pierce but you have such a place in Rindge.

‘To buffer the passage of time’

Center field bleachers at Fenway Park during a 2014 game.

— Photo by Vegasjon

“[Baseball] breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings, and then as soon as the chill rains come, it stops and leaves you to face the fall all alone. You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive, and then just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most, it stops.”

— A. Bartlett Giamatti (1938-1989), a lifelong Red Sox fan who served as president of Yale and baseball commissioner

1917 map of Fenway Park.

1919 rally at Fenway for Irish independence from Britain. Boston had a huge concentration of Irish-Americans.

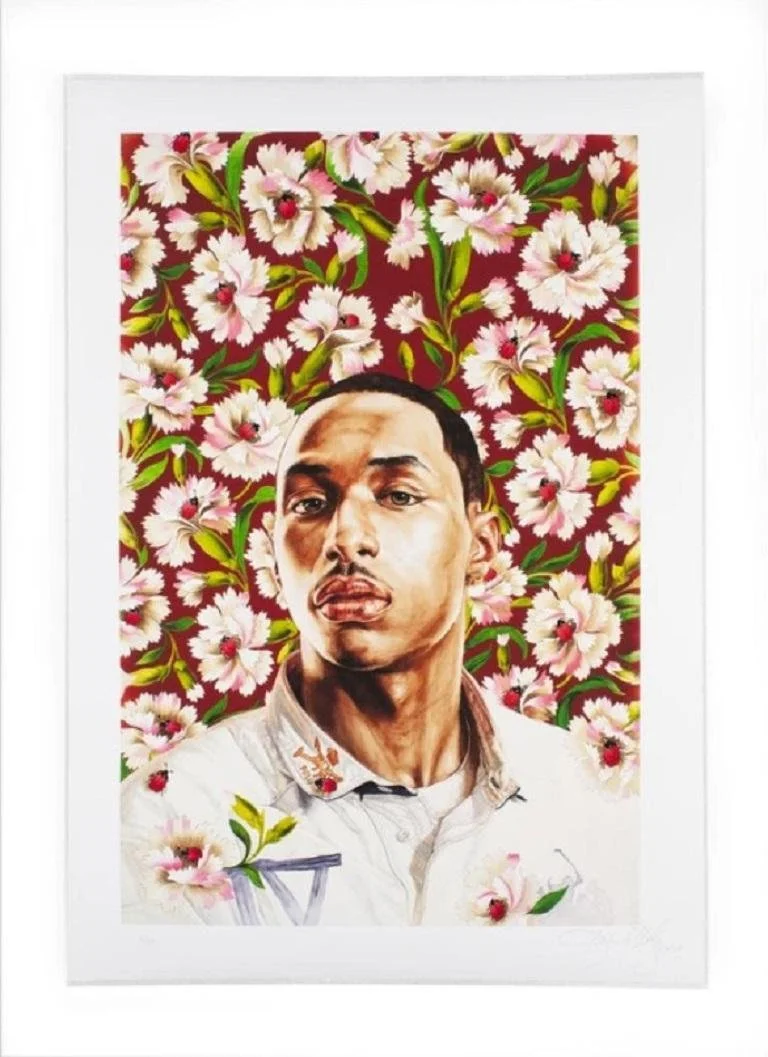

Masculine material

“Sharrod Hosten Study III” (archival ink on paper), by Kehinde Wiley, in the show “Masculine Identities: Filling in the Blank,’’ at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst Fine Arts Center through May 14.

The gallery says that the show explores masculinity and its place in art. “Featuring work by Carlos Villa, Andy Warhol, Kehinde Wiley and Nicole Eisenman, this exhibition aims to take the traditionally masculine traits of rigidity, roughness, strength and control and interpret them in new ways.’’

Llewellyn King: A shrug when it comes to mass murder with guns

AR-15-style assault rifle made by Southport, Conn.-based Sturm, Ruger & Co.

A Smith & Wesson AR-15-style assault rifle, designed to tear apart as many people as possible as fast as possible.

In Maryville, Tenn., where long -Springfield, Mass.-based gun maker Smith & Wesson’s is moving its headquarters. The company makes assault rifles beloved by mass murderers. That has bothered folks in Massachusetts but makes the company popular in gun-cult-dominated Tennessee and other violent Red States.

— Photo by Brian Stansberry

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

“Murder most foul,” cries the ghost of Hamlet’s father to explain his own killing in Shakespeare’s play.

We shudder in the United States when yet more children are slain by deranged shooters. Yet we are determined to keep a ready supply of AR-15-type assault rifles on hand to facilitate the crazy when the insanity seizes them.

The murder in Nashville of three nine-year-olds and three adults should have us at the barricades, yelling bloody murder. Enough! Never again!

But we have mustered a national shrug, concluding that nothing can be done.

Clearly, something can be done; something like reviving the assault rifle ban, which expired after 10 years of statistically proven success.

We are culpable. We think that our invented entitlement to own these weapons, designed for war, is a divine right, outdistancing reason, compassion, and any possible form of control.

The blame rests primarily on something in American exceptionalism that loves guns. I mostly understand that; I like them myself, as I write from time to time. I also like fast cars, small airplanes, strong drink, and other hair-raising things.

But society has said these need controls — from speed limits to flying instruction — and has severe penalties for mixing the first two with the last. Those controls make sense. We abide by them.

When it comes to that other great national indulgence, guns, society has said safety doesn’t count. So far this year, more than 10,000 people have been killed in gun violence. If that were the number of fatalities from disease, we would again be in lockdown.

We have concocted this scared right to keep and use guns. To ensure this, the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution has been manhandled by lawyers into being a justification for putting something deadly out of the reach of social control or even rudimentary discipline.

The latest school shooting has raised our hackles, but not our capacity to act. This national shrug at something which can be fixed is a stain on the body politic.

Most of the conservative wing of the establishment, represented by the Republican Party, has dismissed it as one might a natural disaster.

But the routine murder of innocents in school shootings is a man-made disaster. Worse, it is sanctified by a particular interpretation of the Second Amendment.

It is an interpretation which has demanded, and continues to demand, legal contortionism. This is used to justify the citizenry owning and using weapons of war.

This latest school shooting, which happened in this young year, was shocking, but what was more shocking was the political reaction.

President Biden wrung his hands and said nothing could be done without the support of Congress — thus endorsing a national fatalism.

Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina suggested more policemen in schools, and Rep. Thomas Massie (R.-Tenn.) said teachers needed to be armed. His children are homeschooled.

In personal life and in national life perceived impossibility is hugely debilitating.

Imagine if the Founding Fathers had said the British Empire was too strong to challenge, if FDR had said America couldn’t rise against the forces of the economic chaos of the 1930s, or if Margaret Thatcher had said British trade unions were too strong to be opposed?

These are incidents where perceived reality was, with struggle, trounced for the general good.

Guns along with drugs are the largest killer of young people. They aren’t unrelated. Unregulated guns find their way to the drug gangs of Central America, facilitating the flow of drugs.

On the Senate floor, the chamber’s longtime chaplain, retired Rear Adm. Barry C. Black, took on the pusillanimous members of his flock after the Nashville murders, quoting the 18th-century Anglo-Irish statesman Edmund Burke’s admonition, “The only thing needed for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.” Indubitably.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

A whimsical world

“Flatland From Can You See What I See?: Hidden Wonders!” (pigmented inkjet photo), by Walter Wick, at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, through Sept. 3.

The museum explains:

“The whimsical world of Walter Wick has fascinated people of all ages since 1991, when his first children’s book series I SPY found its way onto the bookshelves of millions of American households. The success of Wick’s books has established him as one of the most celebrated photographic illustrators of all time. A Hartford native, Wick began his artistic career as a landscape photographer before becoming enamored with the technical aspects of studio photography. Wick aspired to master studio techniques, but also to represent such concepts as the perception of space and time in photographs, and experimented with mirrors, time exposures, photo composites, and other tricks to do so. This manipulation of processes and perception has led to a prolific career that has now, over 30 years after the release of I SPY: A Book of Picture Riddles, resulted in the publication of more than 26 children’s books.’’

Ripen, then leave

Victorian-era row houses in Springfield, built in the city’s industrial heyday.

“Springfield, Massachusetts, is a place to be from. Talented people ripen in Springfield, then move away to larger cities to make their fortune.’’ (Like Theodor Geisel, the Springfield native later known as Dr. Seuss.)

— James C. O’Connell, in Pioneer Valley Reader (1995)

David Warsh: Read and reread Kindleberger, with his grasshopper intellect

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Most people know economist Charles. P. Kindleberger, to the extent they know him at all, as the author of Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, (Basic Books, 1978), the best book on its topic since Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market, by Walter Bagehot, in 1873. Fewer understand that the reason that they know Hyman Minsky at all is because Kindleberger devoted the second chapter of his book to him.

Though Minsky was “a man with a reputation among monetary theorists for being particularly pessimistic, even lugubrious, in his emphasis on the fragility of the monetary system and its propensity to disaster… his model lends itself effectively to the interpretation of economic and financial history,” wrote Kindleberger. After that, Minsky became for some a shadow Keynes.

In fact Minsky didn’t really have a model, in the sense the term was used by macroeconomists. Like Kindleberger, he was mostly a literary economist in possession of a narrative, but he was ten years younger and a member of the post-WWII generation. After completing his Ph.D. at Harvard University in 1949, Minsky had taught ten years at Brown University, eight more at University of California at Berkeley and another twenty-five at Washington University in St. Louis before retiring, in 1990. He was, however, one of a relative handful of scholars who took financial intermediation seriously. He published “Central Banking and Money Market Changes,” in the Quarterly Journal of Economics in 1957 and Stabilizing an Unstable Economy (Yale), in 1986. But he never gained altitude in the profession and settled instead for the lesser role of “maverick.” He died in 1996.

CPK, as he was known, on the other hand, was a star, though of lesser magnitude in a Massachusetts Institute of Technology department led by Nobel laureates Paul Samuelson, Robert Solow and Franco Modigliani. Known initially mostly as a textbook writer, Kindleberger’s influence as an international economist grew until he became a Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association, in 1980, and president in 1985. He died in 2003, but Manias, Panics and Crashes has outlived him, though three posthumous editions edited by Robert Aliber, who somewhat broadened its scope. Robert McCauley has edited an eighth.

Now an important new biography has appeared. Money and Empire: Charles P. Kindleberger and the Dollar System (Cambridge, 2022), by Perry Mehrling, of Boston University, brings CPK vividly back to life, in the form of a coming-of-age story about an unusually perspicacious young man’s adventures in the last days of literary economics. The author, Mehrling, is something of a border-crosser himself, an economic biographer who first book, The Money Interest and The Public Interest: American Monetary Thought 1920-1970 (Harvard 1997) profiled economists Allyn Young, Alvin Hansen and Edward Stone Shaw. His Fischer Black and the Revolutionary Idea of Finance (Wiley, 2005) traced the intellectual development and personal life of the co-inventor of the Black-Scholes options pricing formula – “a charming and brilliant book about a charming and brilliant man,” according to Robert Lucas.

Money and Empire is Mehrling’s fourth book. Kindleberger’s serial lives and ideas turn out to have been no less interesting than those of Black. Born to WASPy parents in New York City in 1910, “Charlie” – that’s what nearly everyone called him – attended the Kent School, a boarding school in rural Connecticut, and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania. His father, a prosperous lawyer, had hoped that his only son would become a lawyer, but Charlie spent his summers at sea, sailing around Europe as a merchant seaman.

By then the Great Depression was on. So it was at Columbia University that Kindleberger became an economist, studying under H. Parker Willis, one of the architects of the Federal Reserve System. He then worked as a central banker, from 1936 until 1942; first at the New York Fed; then the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland; finally with the Fed’s Board of Governors in Washington. After America entered World War II, he joined the Office of Strategic Services in London, and became chief of its Enemy Objectives Unit in 1943. After the war, he spent three years at the State Department, working for William Clayton, on developing the Marshall Plan.

Disaster struck in 1948: in the early stage of the McCarthy era, Kindleberger’s security clearance was questioned by the FBI, apparently for remaining in touch with those with whom he had disagreed during negotiations surrounding the Bretton Woods treaty, in 1944. In 1951 it was vacated altogether. The path he had envisaged – civil service, central banking, government work – was foreclosed. The alternative was academia. He accepted an offer from the department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and left the State Department, in 1948.

The rest of Mehrling book is no less dramatic for tracing Kindlebeger’s intellectual engagement in the pressing issues of the day. How would New York and the dollar replace London and the pound sterling as the currency in which global trading would be conducted? There may be no better way for the lay person to follow this complicated story as it unfolded than through the life story of one of its foremost analytic protagonists. Mehring’s grace is extraordinary as he sifts through the reams of Kindleberger’s published books and articles; his private papers, now deposited in archives; and still more revealing family records. Mehrling’s insight is even more striking.

It turns out Kindlebeger’s most important book may have been nearly his last – A Financial History of Western Europe, nearly half of which is devoted to the interwar period and the years after World War II. Ostensibly notes for two courses that Kindleberger taught at the end of the Seventies – the first at the University of Texas at Austin, at the behest of his OSS friend Walt Rostow, the second at MIT – the book is, in Kindleberger’s own phrase, his chef d’oeuvre, an exposition of how the dollar system arose, what it is, and and how it is supposed to work, plus the background necessary to understand it.

There is just one problem. CPK described himself as a grasshopper intellect, hopping from topic to topic. His style is epigrammatic, even telegraphic. Mehrling tries to fill in the outlines of Kindleberger’s fundamentally institutionalist views; as author, though, he is too faithful to the story of his subject’s life to interpose his own opinions more than lightly.

Hence the dual purpose. With one jobs done, another looms. Mehrling’s third book, The New Lombard Street: How the Fed Became the Dealer of Last Resort (Princeton, 2011), was written quickly, in the aftermath of the crisis of 2007-08. Although it was better than almost all of the other analyses tumbling from the presses in those days, it still didn’t quite work. Mehrling’s others books each took most of a decade to write.

It is time now, to settle down to write one more. What are Mehrling’s own views on the prospects for the dollar system in the future of a world increasingly taking sides between the regnant American system and its rival now being gradually assembled in China? If this sort of thing interests, if you want to learn something about international economics up close and personal, then you can’t do better to pass the time than to read Money and Empire: Charles P. Kindleberger and the Dollar System.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Just before or after the greening?

Work by Rebecca Anne Nagle, a Gloucester, Mass.-based artist.

Chris Powell: Teacher raises always fail to reduce poverty in Connecticut

The Truant's Log,” by Ralph Hedley (1899)

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Hardly a week passes without revealing more evidence that poverty is worsening in Connecticut.

As an emergency measure, all public school students in Connecticut are now eligible for free or discounted school lunches for the current school year. But this month it was reported that the number of students who would qualify under the old rules increased by 4% in the year ending last October. The number of students not able to speak English increased by 10%. These data points are the key measures of poverty used by state government for allocating state money to school systems.

Predictably enough, most of both increases involved children in Connecticut's ever-struggling cities.

While the number of state students qualifying for free school lunches had fallen in the prior two years, this seems to have been only because of the federal government's temporary tax credit for people with children. It's not that students suddenly were able to pay for their own lunches but that government was paying for them in a different way. The self-sufficiency of poor families did not increase.

People who consider themselves advocates for children assert that the new data calls for state government to "invest" another $300 million in education in the cities. Actually the new data suggest that state government's long practice of "investing" more in urban education has failed to achieve any substantial increase in learning or any substantial reduction in poverty.

But failure in education and poverty policy long has been the rationale for doing still more of what has failed.

All the extra money "invested" in urban education probably has failed because it has been spent mainly on increasing the compensation of teachers and administrators. The extra money has not made disadvantaged children any more prepared to learn when they get to school, nor has it made their households much less poor and their upbringings much better.

Indeed, though the virus epidemic is long over, chronic absenteeism in Connecticut's schools has risen to an average of 25% and is closer to 50% in the cities. Standardized test results show that student proficiency in Connecticut has been collapsing for more than 10 years. The education and poverty problems have endured no matter how much money has been thrown at them.

But for political reasons this failure of policy has never been audited.

This doesn't mean that teachers are to blame. They play the hand they are dealt -- indifferent, unparented and sometimes incorrigible students. School administrators who stick to such pernicious policies as social promotion and the suspension of discipline are partly to blame. But the problem is still bigger than that -- social disintegration and proletarianization, which begin long before children get to school, and quite without government's objection.

The legislation proposed by a few far-left Democrats in the General Assembly to require people to vote seems to presume this proletarianization -- to presume that the many people who don't vote and the many who don't even register to vote would vote Democratic if they were required to vote, since the Democrats are the party of enlarging government to dispense ever more free stuff and patronage and to increase dependence on government.

The mandatory-voting legislation raises questions that its advocates have yet to answer.

Could the mandatory voting requirement be met by filing a form affirming that a person is aware of an election but doesn't want to vote for anyone?

What would be the penalty for refusing to vote or to file the opt-out form?

Would mandatory voting apply to everyone or only to those people registered to vote?

Would a mandatory voting requirement discourage people from registering to vote in the first place?

Perhaps most important, why would requiring everyone to vote necessarily improve politics, government, and public life?

After all, for years now, half of Connecticut's high school graduates have failed to master high school math and English, most have lacked a basic knowledge of civics, and many carry this ignorance through life. They are being prepared mainly to become lifelong dependents of government.

Of course even the ignorant and uninformed have the right to vote. But why push it so hard?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

'Pulse of color, play of light'

“Rondo” (acrylic, graphite, cold wax and oil paint), by Lexington, Mass.-based artist Marina Thompson.

She writes:

“The pulse of color and the play of light and texture are constant sources of stimulation. Color creates light, light creates form. To generate depth, energy and movement with illusions of volume, space, light and time –

this is why I paint.’’

Town seal of Lexington, where the American Revolutionary War began in earnest.

Martha Bebinger: In Mass. and elsewhere, what next now that some roadblocks to addiction treatment are gone?

A 2007 assessment of harm from recreational drug use (mean physical harm and mean dependence liability): Buprenorphine was ranked 9th in dependence, 8th in physical harm, and 11th in social harm.

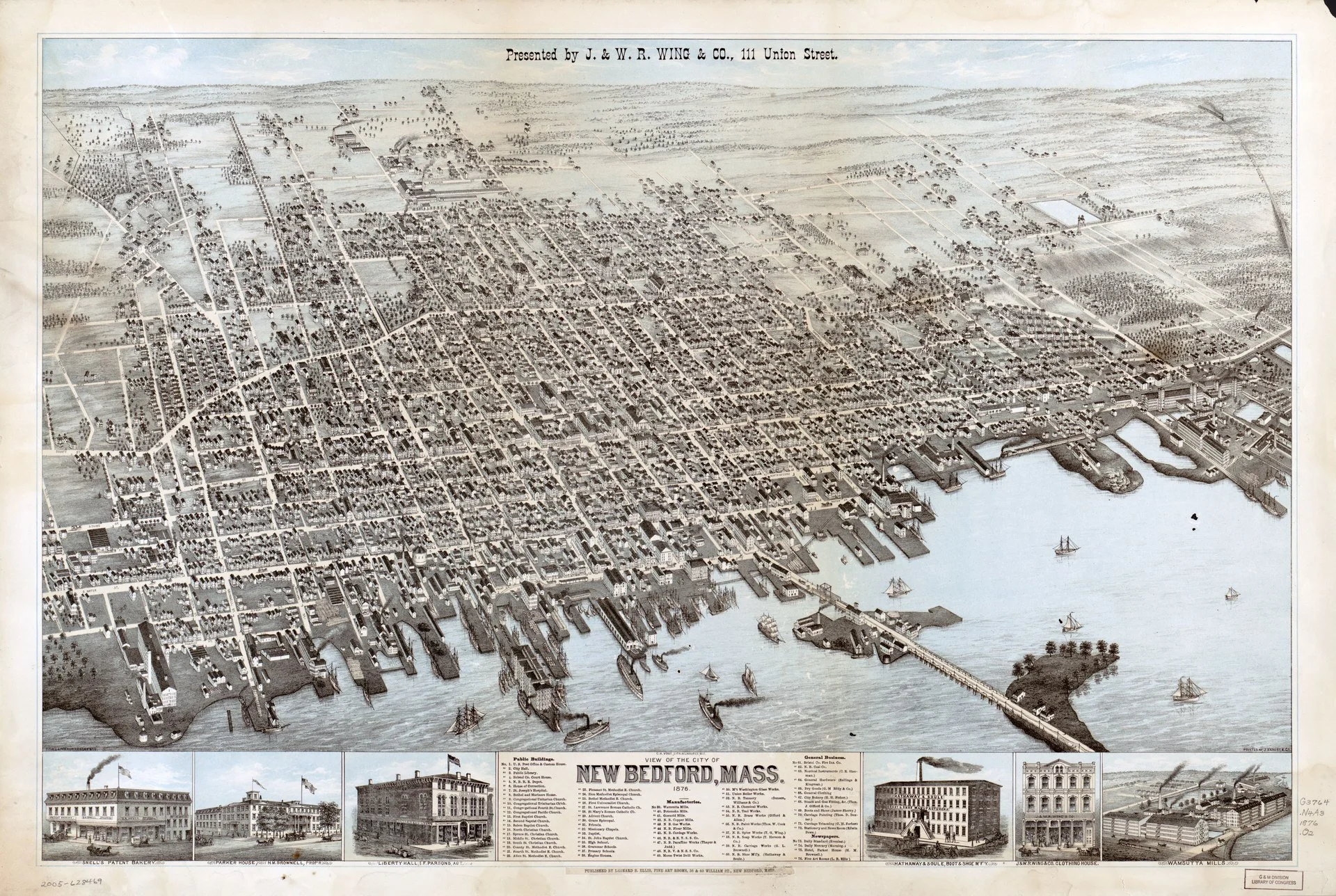

New Bedford in 1876, after the swift decline of the whaling industry as New Bedford became mostly a textile-manufacturing city, like its neighbor Fall River.

BOSTON

For two decades — as opioid overdose deaths rose steadily — the federal government limited access to buprenorphine, a medication that addiction experts consider the gold standard for treating patients with opioid use disorder. Study after study shows it helps people continue addiction treatment while reducing the risk of overdose and death.

Clinicians who wanted to prescribe the medicine had to complete an eight-hour training. They could treat only a limited number of patients and had to keep special records. They were given a Drug Enforcement Administration registration number starting with X, a designation many doctors say made them a target for drug-enforcement audits.

“Just the process associated with taking care of our patients with a substance use disorder made us feel like, ‘Boy, this is dangerous stuff,'” said Dr. Bobby Mukkamala, who chairs an American Medical Association task force addressing substance-use disorder.

“The science doesn’t support that but the rigamarole suggested that.”

That rigamarole is mostly gone. Congress eliminated what became known as the “X-waiver” in legislation President Joe Biden signed late last year. Now begins what some addiction experts are calling a “truth serum moment.”

Were the X-waiver and the burdens that came with it the real reason only about 7% of clinicians in the U.S. were cleared to prescribe buprenorphine? Or were they an excuse that masked hesitation about treating addiction, if not outright disdain for these patients?

There’s great optimism among some leaders in the field that getting rid of the X-waiver will expand access to buprenorphine and reduce overdoses. One study from 2021 shows taking buprenorphine or methadone, another opioid agonist treatment, reduces the mortality risk for people with opioid dependence by 50%. The medication is an opioid that produces much weaker effects than heroin or fentanyl and reduces cravings for those deadlier drugs.

The nation’s drug czar, Dr. Rahul Gupta, said getting rid of the X-waiver would ultimately prevent millions of deaths.

“The impact of this will be felt for years to come,” Gupta said. “It is a true historic change that, frankly, I could only dream of being possible.”

Gupta and others envision obstetricians prescribing buprenorphine to their pregnant patients, infectious disease doctors adding it to their medical toolbox, and lots more patients starting buprenorphine when they come to emergency rooms, primary-care clinics, and rehabilitation facilities.

We are “transforming the way we think to make every moment an opportunity to start this treatment and save someone’s life,” said Dr. Sarah Wakeman, the medical director for substance use disorder at Mass General Brigham, in Boston.

Wakeman said clinicians she has been contacting for the past decade are finally willing to consider treating patients with buprenorphine. Still, she knows stigma and discrimination could undermine efforts to help those who aren’t being served. In 2021, a national survey showed just 22% of people with opioid use disorder received medications such as buprenorphine and methadone.

The test of whether clinicians will step up and if prescribing will become more widespread is underway in hospitals and clinics across the country as patients struggling with addiction queue up for treatment. A woman named Kim, 65, is among them.

Kim’s recent visit to the Greater New Bedford Community Health Center, in southeastern Massachusetts, began in an exam room with Jamie Simmons, a registered nurse who runs the center’s addiction treatment program but doesn’t have prescribing powers. Kaiser Health News agreed to use only Kim’s first name to limit potential discrimination linked to her drug use.

Kim told Simmons that buprenorphine had helped her stay off heroin and avoid an overdose for nearly 20 years. Kim takes a medication called Suboxone, a combination of buprenorphine and naloxone, which comes in the form of thin, filmlike strips she dissolves under her tongue.

“It’s the best thing they could have ever come out with,” Kim said. “I don’t think I ever even had a desire to use heroin since I’ve been taking them.”

Buprenorphine can produce mild euphoria and slow breathing but there’s a ceiling on the effects. Patients like Kim may develop a tolerance and not experience any effects.

“I don’t get high on Suboxones,” Kim said. “They just keep me normal.”

Still, many clinicians have been hesitant to use buprenorphine — known as a partial opioid agonist — to treat an addiction to more deadly forms of the drug.

Kim’s primary-care doctor at the health center never applied for an X-waiver. So for years Kim bounced from one treatment program to another, seeking a prescription. During lapses in her access to buprenorphine, the cravings returned — an especially scary prospect after the powerful opioid fentanyl largely replaced heroin on the streets of Massachusetts, where Kim lives.

“I’ve seen so many people fall out in the last month,” Kim said, using a slang term for overdosing. “That stuff is so strong that within a couple minutes, boom.”

Because fentanyl can kill so quickly, the benefits of taking buprenorphine and other medications to treat opioid-use disorder have increased as deaths linked to even stronger types of fentanyl rise.

Buprenorphine is present in a small percentage of overdose deaths nationwide, 2.6%. Of those, 93% involved a mix of one or more other drugs, often benzodiazepines. Fentanyl is in 94% of overdose deaths in Massachusetts.

“Bottom line is, fentanyl kills people, buprenorphine doesn’t,” Simmons said.

That reality added urgency to Kim’s health center visit because Kim took her last Suboxone before arriving; her latest prescription had run out.

Cravings for heroin could have returned in about a day if she didn’t get more Suboxone. Simmons confirmed the dose and told Kim that her primary care doctor might be willing to renew the prescription now that the X-waiver is not required. But Dr. Than Win had some concerns after reviewing Kim’s most recent urine test. It showed traces of cocaine, fentanyl, marijuana, and Xanax, and Win said she was worried about how the street drugs might interact with buprenorphine.

“I don’t want my patients to die from an overdose,” Win said. “But I’m not comfortable with the fentanyl and a lot of narcotics in the system.”

Kim was adamant that she did not intentionally ingest fentanyl, saying it might have been in the cocaine she said her roommate shares occasionally. Kim said she takes the Xanax to sleep. Her drug use presents complications that many primary care doctors don’t have experience managing. Some clinicians are apprehensive about using an opioid to treat an addiction to opioids, despite compelling evidence that doing so can save patients’ lives.

Win was worried about writing her first prescription for Suboxone. But she agreed to help Kim stay on the medication.

“I wanted to start with someone a little bit easier,” Win said. “It’s hard for me; that’s the reality and truth.”

About half of the providers at the Greater New Bedford health center had an X-waiver when it was still required. Attributing some of the resistance to having the waiver to stigma or misunderstanding about addiction, Simmons urged doctors to treat addiction as they would any other disease.

“You wouldn’t not treat a diabetic; you wouldn’t not treat a patient who is hypertensive,” Simmons said. “People can’t control that they formed an addiction to an opiate, alcohol, or a benzo.”

Searching for Solutions to Soften Stigma

Although the restrictions on buprenorphine prescribing are no longer in place, Mukkamala said the perception created by the X-waiver lingers.

“That legacy of elevating this to a level of scrutiny and caution —that needs to be sort of walked back,” Mukkamala said. “That’s going to come from education.”

Mukkamala sees promise in the next generation of doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants coming out of schools that have added addiction training. The American Medical Association and the American Society of Addiction Medicine have online resources for clinicians who want to learn on their own.

Some of these resources may help fulfill a new training requirement for clinicians who prescribe buprenorphine and other controlled narcotics. It will take effect in June. The DEA has not issued details about the training.

But training alone may not shift behavior, as Rhode Island’s experience shows.

The number of Rhode Island practitioners approved to prescribe buprenorphine increased roughly threefold from 2016 to 2022 after the state said physicians in training should obtain an X-waiver. Still, having the option to prescribe buprenorphine “didn’t open the floodgates” for patients in need of treatment, said Dr. Jody Rich, an addiction specialist who teaches at Brown University. From 2016 to 2022, when the number of qualified prescribers increased, the number of patients taking buprenorphine also increased, but by a much smaller percentage.

“It all comes back to stigma,” Rich said.

He said long-standing resistance among some providers to treating addiction is shifting as younger people enter medicine. But tackling the opioid crisis can’t wait for a generational change, he said. To expand buprenorphine access now, states could use pharmacists, partnered with doctors, to help manage the care of more patients with opioid use disorder, Rich’s research shows.

Wakeman, at Mass General Brigham, said it might be time to hold clinicians who don’t provide addiction care accountable through quality measures tied to payments.

“We’re expected to care for patients with diabetes or to care for patients with heart attack in a certain way and the same should be true for patients with an opioid use disorder,” Wakeman said.

One quality measure to track could be how often prescribers start and continue buprenorphine treatment. Wakeman said it would help also if insurers reimbursed clinics for the cost of staff who aren’t traditional clinicians but are critical in addiction care, like recovery coaches and case managers.

Will Ending the X-Waiver Close Racial Gaps?

Wakeman and others are paying especially close attention to whether eliminating the X-waiver helps narrow racial gaps in buprenorphine treatment. The medication is much more commonly prescribed to white patients with private insurance or who can pay cash. But there are also stark differences by race at some health centers where most patients are on Medicaid and would seem to have equal access to the addiction treatment.

At the New Bedford health center, Black patients represent 15% of all patients but only 6% of those taking buprenorphine. For Hispanics, it is 30% to 23%. Most of the health center patients prescribed buprenorphine, 61%, are white, though white patients make up just 36% of patients overall.

Dr. Helena Hansen, who co-authored a book on race in the opioid epidemic, said access to buprenorphine doesn’t guarantee that patients will benefit from it.

“People are not able to stay on a lifesaving medication unless the immense instability in housing, employment, social supports — the very fabric of their communities — is addressed,” Hansen said. “That’s where we fall incredibly short in the United States.”

Hansen said expanding access to buprenorphine has helped reduce overdose deaths dramatically among all drug users in France, including those with low incomes and immigrants. There, patients with opioid use disorder are seen in their communities and offered a wide range of social services.

“Removing the X-waiver,” Hansen said, “is not in itself going to revolutionize the opioid overdose crisis in our country. We would need to do much more.”

This article is part of a partnership that includes WBUR, NPR and Kaiser Health News.

Martha Bebinger is a journalist with WBUR, in Boston

Those pesky barnacles

“A Mermaid” (1900), by John William Waterhouse

“It was a Maine lobster town —-

each morning boatloads of hands

pushed off for granite

quarries on the islands….

”One night you dreamed

you were a mermaid clinging to a wharf-pile,

and trying to pull

off the barnacles with your hands.’’

— From “Water,’’ by Robert Lowell (1917-1977)