‘Humble observer of the world’

“The Air We Breathe” (oil on canvas), by Bernardson, Mass.-based artist Cameron Schmitz, in her show, “The Space Between,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, May 3-28.

The gallery says:

“Painting is a metaphor for Cameron Schmitz’s perception of life, where she explores the inspiration of tender relationships, and the wonder and despair of being a woman, mother, working artist, and humble observer of the world. Working primarily in the mode of intuitive abstraction, Schmitz has discovered how a painting can create space for both an understanding of life and the valuable admission of not knowing. Her approach to abstract painting is informed by a background in both landscape and figurative painting.”

This building, now housing the Bernardson Historical Society, was formerly the home of the historically important educational institution called The Powers Institute.

Trying to understand offshore wind turbines' ecological effects

Wind energy lease areas off the southern coasts of Massachusetts and Rhode Island as of October, 2022

From Mary Lhowe’s very valuable article in ecoRI News:

“{C}an wind turbines off the coast of Rhode Island live up to their renewable energy promise? And what effects will they have on life in the sea?

“Hundreds of experts from the U.S. Department of the Interior down to local fishermen and town planners are puzzling over these questions, especially now, during the permitting and approval process of the Revolution Wind project, in which developers Ørsted and Eversource hope to install up to 100 wind turbines on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) about 18 miles southeast of Point Judith. Cables to transmit power to the grid would make landfall in North Kingstown, and the project is expected to be online by 2025. The Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the project was published last fall.’’

Jim Hightower: Would they kill your granny to make a buck?

From OtherWords.org

There are industries that occasionally do something rotten. And there are industries, such as Big Oil, Big Pharma and Big Tobacco, that persistently do rotten things.

Then there is the nursing-home industry — where rottenness has become a core business principle.

The end-of-life experience can be rotten enough on its own, with an assortment of natural indignities bedeviling us. Good nursing homes help patients gently through this time. In the past couple of decades, though, an entirely unnatural force has come to dominate the delivery of aged care: profiteering corporate chains and Wall Street speculators.

The very fact that this essential and sensitive social function, which ought to be the domain of health professionals and charitable enterprises, is now called an “industry” reflects a total perversion of its purpose.

Some 70 percent of nursing homes are now corporate operations, often run by absentee executives who have no experience in nursing homes and who are guided by the market imperative of maximizing investor profits. They constantly demand “efficiencies” from their facilities — which invariably means reducing the number of nurses, which invariably reduces care, which means more injuries, illness and deaths.

As one nursing expert quoted by The New Yorker rightly says, “It’s criminal.”

But it’s not against the law, since the industry’s lobbying front — a major donor to congressional campaigns — effectively writes the laws, which lets corporate hustlers provide only one nurse on duty, no matter how many patients are in the facility.

When a humane nurse-staffing requirement was proposed last year, the lobby group furiously opposed it, and Congress dutifully bowed to industry profits over grandma’s decent end-time. After all, granny probably doesn’t make campaign donations.

So, as a health-policy analyst bluntly puts it, “The only kind of groups that seem to be interested in investing in nursing homes are bad actors.” To help push for better, contact TheConsumerVoice.org.

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker.

Artists from the top of the world

By Tibet native Tashi Norbu, in the group show “Across Shared Waters,’’ at the Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, Mass., through July 16.

— Photo courtesy artist.

The museum says:

“Across Shared Waters’’ is exhibition of work by contemporary artists of Himalayan heritage alongside traditional Tibetan Buddhist artwork from the Jack Shear Collection. The work explore "themes of identity, consumerism, place, and cultural expectations." Some use traditional Tibetan cultural markers while others work outside of that framework.

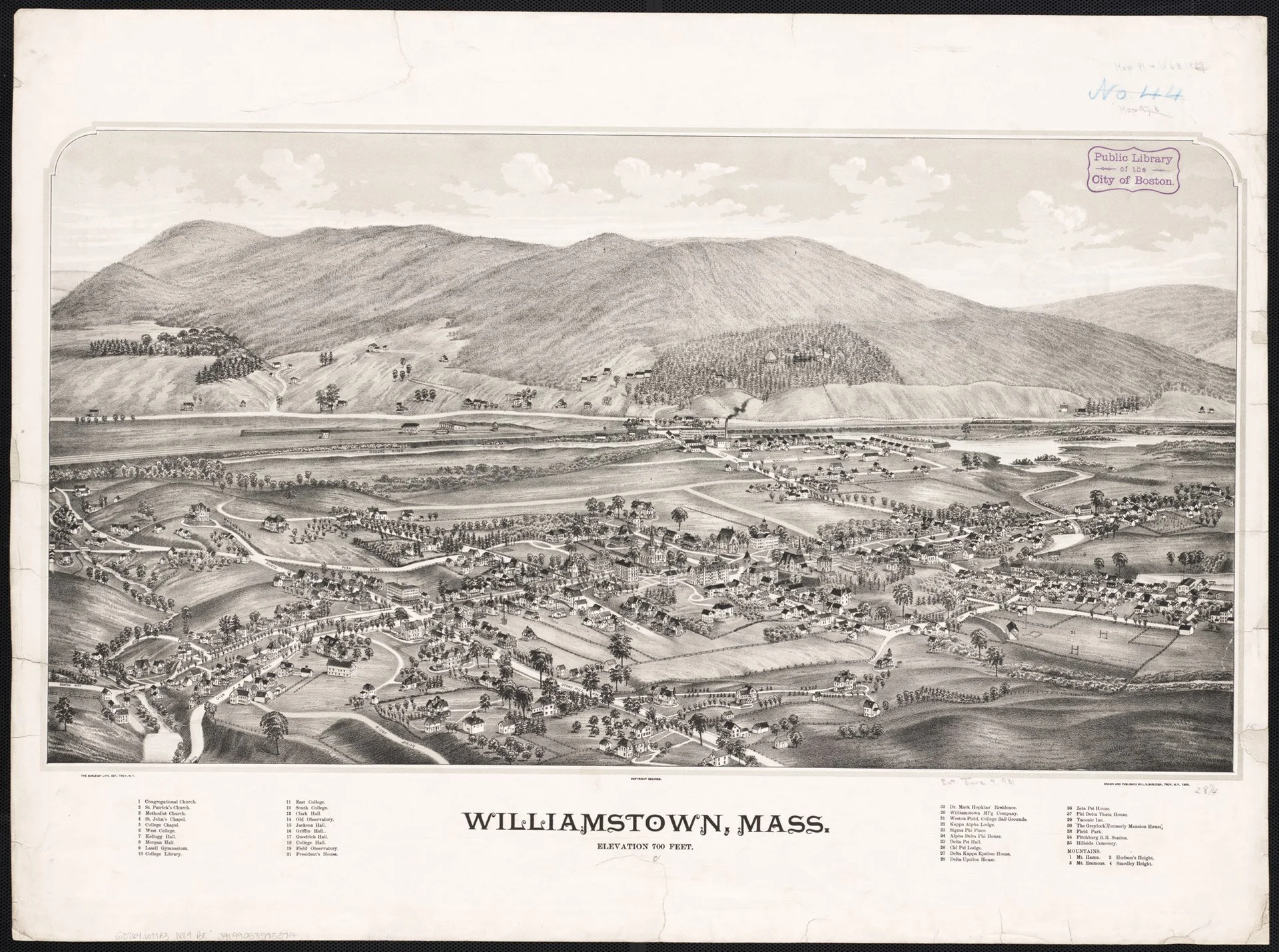

Main Street in Williamstown

1880’s map, with Mt. Greylock looming.

Just a quick kiss

“Petite Confidence” (steel), by Franco-American artist Pascal Pierme, in his show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through March 18.

He says:

“{The late French President| Francois Mitterrand said, ‘I love the person who is searching, yet I am afraid of the one who thinks he has found the answer.’ In my life I have much more pleasure with the questions than with finding the answers, except when the answer is a new question. And that is where the obsession to create begins.

‘‘...For decades, balance, movement, inquiry, architecture and nature have been reoccurring themes in my work. I am interested in assimilating what is not supposed to fit – the combining of contrasting elements. My main ingredient is chemistry. I feel the movement and then freeze that moment in the interaction and take a ‘snapshot’ – capturing a split second in the evolution. Thereby creating something that is abstract and at the same time, quite figurative. As such, my work can be experienced as organic. It moves. It is alive, it comes from somewhere, it is going somewhere, and you feel that by what you see.

‘‘I try to sculpt in a way where I can change my mind until the last minute. My creativity is at its best when I push the medium of my work to its limit.’’

Death village

Water Street in Stonington, Conn.

“Shortly before I died,

Or possibly after,

I moved to a small village by the sea….

The rocky sliver of land, the little houses where the fishermen once lived.…”

— From “In the Village,’’ by James Longenbach (1959-2022), America poet. The poem is inspired by his time in Stonington, Conn.

The origins of the U.S. Valentine’s Day card business

Esther Howland Valentine card, "Affection" ca. 1870s

Edited from a New England Historical Society report:

“Worcester once reigned as the Valentine Capital of the United States. Esther Howland, born in Worcester in 1828, went into the Valentine business in her home town after graduating from Mount Holyoke College. It grew into the world’s largest greeting-card enterprise, until World War II caused paper shortages that put an end to the business. Her company was called the New England Valentine Co.’’

New program to use blood tests to identify Alzheimer’s risk

On Butler Hospital’s verdant campus, on the mostly affluent East Side of Providence. Founded in 1844, it’s one of the oldest hospitals in America for the treatment of psychiatric and neurological illnesses. It has treated more than a few well-known people.

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report

Brown University, in Providence, is partnering with the Memory and Aging Program of Butler Hospital, in Providence, to start a new BioFinder aimed at developing new methods to access risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease.

The study will look at blood tests of individuals between 50 and 80 who are currently healthy but face higher risk for developing Alzheimer’s than the general population. It will include 200 participants overseen by Brown and 400 by Lund University, in Lund, Sweden.

“Developing easy-to-use blood tests will lead to early diagnosis and treatment and be a game-changer in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Stephen Salloway, the principal investigator of the BioFinder-Brown site.

Can’t run the Nutmeg state at the same time

The governor’s mansion in Hartford.

“I’m having trouble managing the mansion {official governor’s residence in Hartford}. What I need is a wife.’’

—Ella T. Grasso (1919-1981), a moderate Democrat who was Connecticut’s governor from 1975 to 1980, when she resigned because of illness.

‘Bringing The Holy Land Home’

Photographic composite showing roundels surrounded by partial Latin text in the show “Bringing the Holy Land Home: The Crusades, Chertsey Abbey, and the Reconstruction of a Medieval Masterpiece” in the Iris and B. Cantor Art Gallery, at The College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, through April 6.

— Photo © Janis Desmarais and Amanda Luyster.

The gallery says that the exhibition is focused on “the famed Chertsy Combat Tiles, a series of tiles that was created around 1250 forChertsey Abbey, in England. This exhibit includes artwork on loan from the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the (Boston) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The tiles are put into context alongside Islamic and Byzantine artwork that lends a wider view to the historical works.’’

A business transaction

“The Knave of Hearts - The King Samples the Tarts” (oil on paper on board), by Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966), at the National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, R.I.

— Copyright the National Museum of American Illustration

Parrish was an important member of the famous art colony in Cornish, N.H., where he had an estate called The Oaks, which is still standing. See the Saint-Gaudens National Historical Park, also in Cornish. The famously reclusive writer J.D. Salinger lived in Cornish.

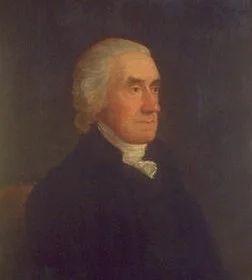

Video: Explaining the colorful career of a too little known Founding Father

Portrait of Robert Treat Paine, by Edward Savage and John Coles, Jr.

— Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston.

A descendent, Thomas M. Paine, tells us the riveting story of American Founding Father/signer of The Declaration of Independence, lawyer, prosecutor, judge, politician and science-and-technology enthusiast {hit this link for video} Robert Treat Paine (1731-1814). (He had a special interest in gunpowder and fireworks and in clocks. )

In legal and government settings, the courageous and eloquent Paine was known for the frequency of his objections.

Statue of Robert Treat Paine, by Richard E. Brooks (1904), in Taunton, Mass., where Paine was mostly based in 1761-1780.

Llewellyn King: What made me an AI enthusiast.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have gone over. All the way. I have fallen in love with artificial intelligence. We need it, and I’m on board.

My conversion was sudden. It happened on one memorable day, Feb. 8, 2023. It was a sudden strike in a well-worn heart by Cupid’s arrow.

My love life with technology has been either unrequited or messy. I was always the one who blew the relationship, I admit that.

It started with computer typesetting. I was a committed hot-lead-type man. I didn’t want to see that painted lady, computer technology, destroying my divine relationship with hot type. But she did and when I tried to make amends, she was, er, cold, froze me out.

Likewise, as an old-time newspaperman, I was very proficient and happy with Telex. Computer technology separated us.

The worst of all was my first encounter with the internet.

I was pursuing the story of nuclear fusion at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, in California. A lab technician tried to interest me in the new device he was using to send messages: the Internet. I blew it off. “That is just Telex on steroids,” I said.

Ms. Internet doesn’t care to be scorned and she nearly cost me my manhood — well, my publishing company — when she took her terrible revenge. She killed print papers as well as hot type. She was a vengeful siren that way.

My conversion to AI began innocently enough. I was listening to a reporter on National Public Radio explaining how Microsoft’s new AI search engine would not only change the world of online searching but would also give Google a serious run for its money — billions of dollars, I might say parenthetically.

The writing's on the wall for Google unless it can get its AI to market fast. I was intrigued.

The illustration used by NPR reporter Bobby Allyn was that of buying a couch and carrying it home in your car. The new search engine, Allyn explained, will tell you if the couch you want to buy will fit in your car. It will know the dimensions of the car and, maybe, of the couch too. Wow!

Then I went on to watch a wild, unruly hearing before the U.S. House Oversight Committee. A long-suffering panel of former Twitter executives faced some pointed abuse from the Republican members. Some of those members never got to pose a question: Their time was entirely taken up castigating the witnesses over alleged collusion with the Biden administration and over Hunter Biden’s laptop — the holy grail for conspiracy theorists. It was a performance worthy of a Soviet show trial.

The worst aspects of the new House were on display. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D.-N.Y.) was visibly flustered because she wasn’t in her seat when her time to question the witnesses arrived. She rushed back to it and was so excitable that she was nearly incoherent.

Then there was Marjorie Taylor Greene (R.-Ga.), who was adamant that Twitter was advancing a political agenda by accepting the science that vaccines helped control the COVID-19 outbreak. She asserted that Twitter had a political objective when it denied her free-speech rights by suspending her account, after frequent warnings about her dangerous public health positions opposing vaccinations.

The lady's not for turning. Not by facts, anyway. That was clear. Any Southern charm she may possess was shelved in favor of invective. She told the former Twitter executives that she was glad they had been fired.

The clincher in my conversion to AI had nothing to do with the brutal thrashing of the experts, but with the explanation by Yoel Roth, former head of Trust and Safety at Twitter, who with forbearance explained that there were then and are now hundreds of Russian false accounts on Twitter aimed at influencing our elections and reaching deeply into our politics. Likewise, Iranian and Chinese accounts.

That is when it occurred to me: AI is the answer. Not the answer to the mannerless ways of the House hearing, but to the whole vulnerability of social media.

We have to fight cyber excess with cyber: Only AI can deal with the volumes of malicious domestic and foreign material on the net. Too bad it won’t resolve the free-speech issues, or the one that emerged at the House hearing: the right to lie without restraint.

This AI doubter is now an enthusiast. Bring it on.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington. D.C.

The flippers make Mass. housing crisis worse

“There Goes the Neighborhood (mixed-media installation), by Brookline-based Ronni Komarow, at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, March 2-April 2.

She explains:

"In 2021, business entities purchased nearly 6,600 single-family homes in Massachusetts, more than 9 percent of all single-family homes sold and nearly double the rate of such purchases a decade before. Investors and other businesses...spent more than $5.6 billion in Massachusetts purchasing these properties, the majority in cash, to rent or flip as the state’s housing market rises.

“Investors are spurred by high demand for housing, rising rents and soaring home values, making it a lucrative business. But housing advocates say the trend is making it harder for individual homeowners to buy and driving up rents, so renters get priced out….

“As an advocate for historic preservation in Boston, I'm mindful that many of these would-be buyers would demolish a purchased home quickly and replace it with the largest, cheapest structure possible, to be sold at the greatest profit. None of these would-be buyers live in the city or have any interest in neighborhoods, community preservation, or quality of life for local residents.’’

Those not entirely wasted hours at journo-favored bars

— Photo by Ragesoss

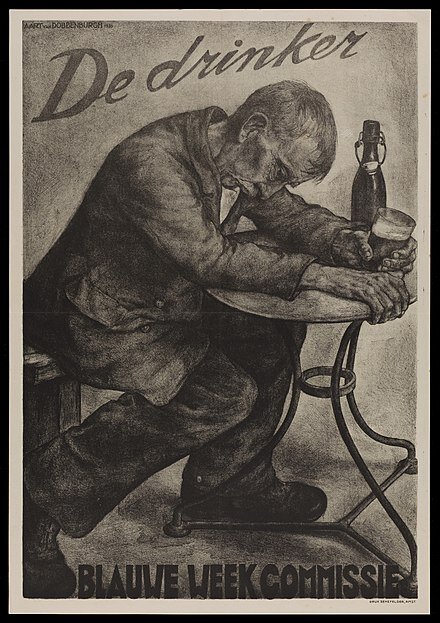

A 1936 anti-drinking poster by Aart van Dobbenburgh

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

For various reasons, going to New York City, as I did recently, reminds me of the bars that we newspaper and magazine reporters and editors used to patronize. This wasn’t a particularly healthy practice, but these places planted some evergreen memories.

Some of the joints I most remember:

Foley’s, in Boston, beloved of Boston Herald Traveler, Record American and Globe editors and reporters, especially scruffy police reporters, with their tales of gruesome or comic crimes and police and political corruption, and news and copy editors having their “lunch” at around 8:30 p.m. between edition deadlines.

Some actually consumed the bar’s pickled eggs as they knocked back their boilermakers --- a shot of whiskey followed by a beer, or pouring a shot of whiskey into their beers and then chugging that – or downing other, not very elegant beverages. I was often amazed that some of these journos could function at all under deadline pressure upon returning to the newsroom after “lunch” at Foley’s. Certainly many of them looked ill and aged fast. Some had noses that were tributes to the distillers’ art.

The older guys (and virtually all these colleagues were men) told vivid stories going back to the ’40s of life in what was then a gritty city. Others were taciturn, as if battered into silence by bad hours and what they had seen and heard on the job in a business in which grim news usually sells better than good.

Then there was the bar off Broad Street in Lower Manhattan where a couple of Wall Street Journal editing colleagues and I would occasionally retreat in mid-evening after work. (We’d stop working soon after listening to WQXR, then The New York Times’s radio station, to learn if we had missed a story that our biggest rival had so we could make necessary adjustments. The station helpfully broadcast a review of its next day’s Page One at 9 p.m.)

One night we came across what appeared to be a corpse on the sidewalk outside the bar that appeared to have been there for a while. A cop came along to deal with the body. (The neighborhood was virtually deserted at night in those days because few people lived there then and there were few food stores, etc., to serve them. Now there are many apartment buildings, put up during the off-and-on boom years from the mid-‘90s to COVID, and so it has much more of a 24/7 feel, though less than before the pandemic.)

In the bar we almost got into a fist fight with a drunk who insulted our colleague Ruth; in the event, he was evicted from the establishment.

I well recall the bar/restaurant in Wilmington, Del., called The Bar Door. That’s where some of us working for the News Journal, The First State’s statewide rag, then owned by the remarkably kindly DuPont family, would lunch at least once or twice a week. My colleagues there were the most abstemious of the newspaper types I hung out with in my career, usually just confining themselves to a Rolling Rock beer. And the food, especially softshell crab from nearby Chesapeake Bay, was good, so there was less drinking on empty stomachs.

The local pols, such as, I think, Joe Biden, then a recently elected U.S. senator, would show up to gossip. My favorite was Melvin Slawik, the charming New Castle County (which includes Wilmington) executive, who was a font of stories, including very funny, self-deprecating ones about himself. He later served time for perjury, obstruction of justice and bribery. He was one of the most likeable people I’ve ever met.

There was Le Village, a bar and restaurant dangerously close to the offices of the International Herald Tribune, in the affluent Paris inner suburb of Neuilly. Because French labor law mandates frequent work breaks, too many of the staff spent too much time there drinking, and, as at all journalist hangouts in those days, smoking. Several were what you might call merely recreational alcoholics. (Growing up, I learned enough about alcoholics, recreational and full time, to last me several lifetimes.)

As the finance editor, in charge of overseeing a third of the paper, I was sometimes put in the awkward position of trying to stop the working-hours drinking of people reporting to me. In one case, I had to remove an engaging and smart, but too often drunk, colleague from consideration for a promotion. In any case, labor law sharply restricted disciplining staffers. It was tough to hire people and even tougher to fire them.

There were other journo bars too, where I heard wild stories that could be the bases of a few novels and/or film-noirish movies, some of which stories were actually true. But my time in such places mostly ended about 30 years ago. One reason I’m still alive.

Oh, yes! There was a bar called Hope’s that was heavily patronized by Providence Journal people, and owned by two of them, but I only made a few clinical research visits.

Malcolm Muggeridge (1903-1990), the great English journalist, satirist, spy, womanizer and late-in-life religious fanatic, once said something to the effect that he regretted the smoking he did, but not the drinking, because of the stories and camaraderie he got out of the latter. But drinking and smoking are two devils embracing.

Great circle route

“Circle Party” (encaustic on panel), by Willa Vennema, a Portland-based painter.

Her Web site notes:

“As teachers, both Vennema and her husband are able to spend the summer with their two children, Oriana, and Casey. They quickly settle in to ‘Island Time,’ on Swan’s Island, a small island off Mt. Desert Island, where Vennema's family has summered for over 53 years. Here, Vennema paints the waters, woods, rocks and trees of Swan's and surrounding islands ‘en plain air’ using acrylic paints. During the winter months, back in her home studio in Portland, Vennema pushes herself to experiment. Her studio works are executed using the hot wax medium known as encaustic, and these works have ranged from semi-abstract landscapes, to fully abstract mixed media works.’’

Burnt Coat Harbor Light, on Swan’s Island.

Arthur Allen: Not profitable enough for CVS

Parenteral formula

NEW YORK — The fear started when a few patients saw their nurses and dietitians posting job searches on LinkedIn.

Word spread to Facebook groups, and patients started calling Coram CVS, a major U.S. supplier of the compounded IV nutrients on which they rely for survival. To their dismay, CVS Health, based in Woonsocket, R.I., confirmed the rumors on June 1: It was closing 36 of the 71 branches of its Coram home-infusion business and laying off about 2,000 nurses, dietitians, pharmacists and other employees.

Many of the patients left in the lurch have life-threatening digestive disorders that render them unable to eat or drink. They depend on parenteral nutrition, or PN — in which amino acids, sugars, fats, vitamins, and electrolytes are pumped, in most cases, through a specialized catheter directly into a large vein near the heart.

The day after CVS’s move, another big supplier, Optum Rx, announced its own consolidation. Suddenly, thousands would be without their highly complex, shortage-plagued, essential drugs and nutrients.

“With this kind of disruption, patients can’t get through on the phones. They panic,” said Cynthia Reddick, a senior nutritionist who was let go in the CVS restructuring.

“It was very difficult. Many emails, many phone calls, acting as a liaison between my doctor and the company,” said Elizabeth Fisher Smith, a 32-year-old public-health instructor in New York City, whose Coram branch was closed. A rare medical disorder has forced her to rely on PN for survival since 2017. “In the end, I got my supplies, but it added to my mental burden. And I’m someone who has worked in health care nearly my entire adult life.”

CVS had abandoned most of its less lucrative market in home parenteral nutrition, or HPN, and “acute care” drugs like IV antibiotics. Instead, it would focus on high-dollar, specialty intravenous medications like Remicade, which is used for arthritis and other autoimmune conditions.

Home and outpatient infusions are a growing business in the United States, as new drugs for chronic illness enable patients, health care providers, and insurers to bypass in-person treatment. Even the wellness industry is cashing in, with spa storefronts and home hydration services.

But while reimbursement for expensive new drugs has drawn the interest of big corporations and private equity, the industry is strained by a lack of nurses and pharmacists. And the less profitable parts of the business — as well as the vulnerable patients they serve — are at serious risk.

This includes the 30,000-plus Americans who rely for survival on parenteral nutrition, which has 72 ingredients. Among those patients are premature infants and post-surgery patients with digestive problems, and people with short or damaged bowels, often the result of genetic defects.

While some specialty infusion drugs are billed through pharmacy benefit managers that typically pay suppliers in a few weeks, medical plans that cover HPN, IV antibiotics, and some other infusion drugs can take 90 days to pay, said Dan Manchise, president of Mann Medical Consultants, a home-care consulting company.

In the 2010s, CVS bought Coram, and Optum bought up smaller home infusion companies, both with the hope that consolidation and scale would offer more negotiating power with insurers and manufacturers, leading to a more stable market. But the level of patient care required was too high for them to make money, industry officials said.

“With the margins seen in the industry,” Manchise said, “if you’ve taken on expensive patients and you don’t get paid, you’re dead.”

In September, CVS announced its purchase of Signify Health, a high-tech company that sends out home-health workers to evaluate billing rates for “high-priority” Medicare Advantage patients, according to an analyst’s report. In other words, as CVS shed one group of patients whose care yields low margins, it was spending $8 billion to seek more profitable ones.

CVS “pivots when necessary,” spokesperson Mike DeAngelis told KHN. “We decided to focus more resources on patients who receive infusion services for specialty medications” that “continue to see sustained growth.” Optum declined to discuss its move, but a spokesperson said the company was “steadfastly committed to serving the needs” of more than 2,000 HPN patients.

DeAngelis said CVS worked with its HPN patients to “seamlessly transition their care” to new companies.

However, several Coram patients interviewed about the transition indicated that it was hardly smooth. Other HPN businesses were strained by the new demand for services, and frightening disruptions occurred.

Smith had to convince her new supplier that she still needed two IV pumps — one for HPN, the other for hydration. Without two, she’d rely partly on “gravity” infusion, in which the IV bag hangs from a pole that must move with the patient, making it impossible for her to keep her job.

“They just blatantly told her they weren’t giving her a pump because it was more expensive, she didn’t need it, and that’s why Coram went out of business,” Smith said.

Many patients who were hospitalized at the time of the switch — several inpatient stays a year are not unusual for HPN patients — had to remain in the hospital until they could find new suppliers. Such hospitalizations typically cost at least $3,000 a day.

“The biggest problem was getting people out of the hospital until other companies had ramped up,” said Dr. David Seres, a professor of medicine at the Institute of Human Nutrition at Columbia University Medical Center. Even over a few days, he said, “there was a lot of emotional hardship and fear over losing long-term relationships.”

To address HPN patients’ nutritional needs, a team of physicians, nurses, and dietitians must work with their supplier, Seres said. The companies conduct weekly bloodwork and adjust the contents of the HPN bags, all under sterile conditions because these patients are at risk of blood infections, which can be grave.

As for Coram, “it’s pretty obvious they had to trim down business that was not making money,” Reddick said, adding that it was noteworthy both Coram and Optum Rx “pivoted the same way to focus on higher-dollar, higher-reimbursement, high-margin populations.”

“I get it, from the business perspective,” Smith said. “At the same time, they left a lot of patients in a not great situation.”)

Smith shares a postage-stamp Queens apartment with her husband, Matt; his enormous flight simulator (he’s an amateur pilot); cabinets and fridges full of medical supplies; and two large, friendly dogs, Caspian and Gretl. On a recent morning, she went about her routine: detaching the bag of milky IV fluid that had pumped all night through a central line implanted in her chest, flushing the line with saline, injecting medications into another saline bag, and then hooking it through a paperback-sized pump into her central line.

Smith has a connective tissue disorder called Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which can cause many health problems. As a child, Smith had frequent issues, such as a torn Achilles tendon and shoulder dislocations. In her 20s, while working as an EMT, she developed severe gut blockages and became progressively less able to digest food. In 2017, she went on HPN and takes nothing by mouth except for an occasional sip of liquid or bite of soft food, in hopes of preventing the total atrophy of her intestines. HPN enabled her to commute to George Washington University, in Washington, D.C., where in 2020 she completed a master’s in public health.

On days when she teaches at LaGuardia Community College — she had 35 students this semester — Smith is up at 6 a.m. to tend to her medical care, leaves the house at 9:15 for class, comes home in the afternoon for a bag of IV hydration, then returns for a late afternoon or evening class. In the evening she gets more hydration, then hooks up the HPN bag for the night. On rare occasions she skips the HPN, “but then I regret it,” she said. The next day she’ll have headaches and feel dizzy, sometimes losing her train of thought in class.

Smith describes a “love-hate relationship” with HPN. She hates being dependent on it, the sour smell of the stuff when it spills, and the mountains of unrecyclable garbage from the 120 pounds of supplies couriered to her apartment weekly. She worries about blood clots and infections. She finds the smell of food disconcerting; Matt tries not to cook when she’s home. Other HPN patients speak of sudden cravings for pasta or Frosted Mini-Wheats.

Yet HPN “has given me my life back,” Smith said.

She is a zealous self-caretaker, but some dangers are beyond her control. IV feeding over time is associated with liver damage. The assemblage of HPN bags by compounding pharmacists is risky. If the ingredients aren’t mixed in the right order, they can crystallize and kill a patient, said Seres, Smith’s doctor.

He and other doctors would like to transition patients to food, but this isn’t always possible. Some eventually seek drastic treatments such as bowel lengthening or even transplants of the entire digestive tract.

“When they run out of options, they could die,” said Dr. Ryan Hurt, a Mayo Clinic physician and president of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.

xxx

And then there are the shortages.

In 2017, Hurricane Maria crippled dozens of labs and factories making IV components in Puerto Rico; next came the covid-19 emergency, which shifted vital supplies to gravely ill hospital patients.

Prices for vital HPN ingredients can fluctuate unpredictably as companies making them come and go. For example, in recent years the cost of the sodium acetate used as an electrolyte in a bag of HPN ballooned from $2 to $25, then briefly to $300, said Michael Rigas, a co-founder of the home infusion pharmacy KabaFusion.

“There may be 50 different companies involved in producing everything in an HPN bag,” Rigas said. “They’re all doing their own thing — expanding, contracting, looking for ways to make money.” This leaves patients struggling to deal with various shortages from saline and IV bags to special tubing and vitamins.

“In the last five years I’ve seen more things out of stock or on shortage than the previous 35 years combined,” said Rigas.

The sudden retrenchment of CVS and Optum Rx made things worse. Another, infuriating source of worry: the steady rise of IV spas and concierge services, staffed by moonlighting or burned-out hospital nurses, offering IV vitamins and hydration to well-off people who enjoy the rush of infusions to relieve symptoms of a cold, morning sickness, a hangover, or just a case of the blahs.

In January, infusion professionals urged FDA Commissioner Robert Califf to examine spa and concierge services’ use of IV products as an “emerging contributing factor” to shortages.

The FDA, however, has little authority over IV spas. The Federal Trade Commission has cracked down on some spa operations — for unsubstantiated health claims rather than resource misuse.

Bracha Banayan’s concierge service, called IVDRIPS, started in 2017 in New York City and now employs 90 people, including 60 registered nurses, in four states, she said. They visit about 5,000 patrons each year, providing IV hydration and vitamins in sessions of an hour or two for up to $600 a visit. The goal is “to hydrate and be healthy” with a “boost that makes us feel better,” Banayan said.

Although experts don’t recommend IV hydration outside of medical settings, the market has exploded, Banayan said: “Every med spa is like, ‘We want to bring in IV services.’ Every single paramedic I know is opening an IV center.”

Matt Smith, Elizabeth’s husband, isn’t surprised. Trained as a lawyer, he is a paramedic who trains others at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “You give someone a choice of go up to some rich person’s apartment and start an IV on them, or carry a 500-pound person living in squalor down from their apartment,” he said. “There’s one that’s going to be very hard on your body and one very easy on your body.”

The very existence of IV spa companies can feel like an insult.

“These people are using resources that are literally a matter of life or death to us,” Elizabeth Smith said.

Shortages in HPN supplies have caused serious health problems including organ failure, severe blisters, rashes, and brain damage.

For five months last year, Rylee Cornwell, 18 and living in Spokane, Washington, could rarely procure lipids for her HPN treatment. She grew dizzy or fainted when she tried to stand, so she mostly slept. Eventually she moved to Phoenix, where the Mayo Clinic has many Ehlers-Danlos patients and supplies are easier to access.

Mike Sherels was a University of Minnesota football coach when an allergic reaction caused him to lose most of his intestines. At times he’s had to rely on an ethanol solution that damages the ports on his central line, a potentially deadly problem “since you can only have so many central access sites put into your body during your life,” he said.

When Faith Johnson, a 22-year-old Las Vegas student, was unable to get IV multivitamins, she tried crushing vitamin pills and swallowing the powder, but couldn’t keep the substance down and became malnourished. She has been hospitalized five times this past year.

Dread stalks Matt Smith, who daily fears that Elizabeth will call to say she has a headache, which could mean a minor allergic or viral issue — or a bloodstream infection that will land her in the hospital.

Even more worrying, he said: “What happens if all these companies stop doing it? What is the alternative? I don’t know what the economics of HPN are. All I know is the stuff either comes or it doesn’t.”

Arthur Allen is Kaiser Health News reporter.

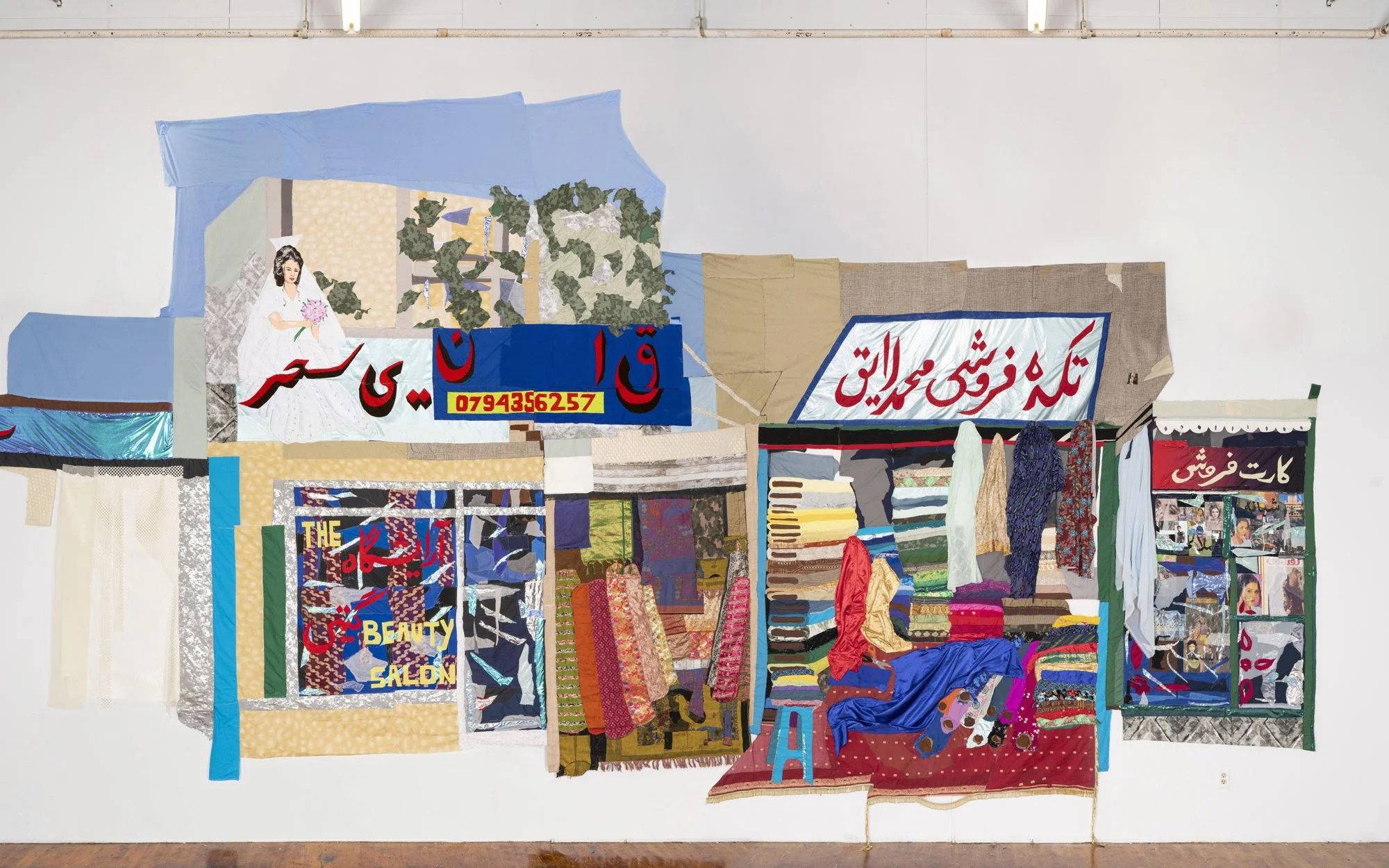

Homage to a lost home

In Hangama Amiri’s show “A Homage to Home,’’ at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Conn., through June 11.

The museum says:

“Afghan Canadian artist Hangama Amiri combines painting and printmaking techniques with textiles, weaving together stories based on memories of her homeland and her diasporic experience. She fled Kabul with her family in 1996 when she was 7.’’

No owners in off season

On The Great Beach (aka Nauset Beach) of the Cape Cod National Seashore.

— Photo by Donna Benevides

“In the ‘off’ and empty season, after the tides have erased all signs of a hundred thousand human feet, it was hard to believe that the beach could be owned or claimed by anyone.’’

— John Hay (1915-2011), nature writer, in The Great Beach