Darker times back then

“White Angel Breadline 1932’’ (gelatin silver enlargement print), by Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), at the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H.

Tax challenges in a resort town

Colonial era buildings in a Newport historic district.

— Photo by Daniel Case

Newport Tax Change

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Newport has adopted a new two-tier residential tax system that may cut taxes for many homeowners. The people who would get the break include owners of single-family homes who prove that they’re residents of the City by the Sea for more than seven months a year as well as owners of residential rental properties of three or fewer units whose renters’ leases run for at least a year.

The tax rate will remain higher for non-owner-occupied housing.

Earlier this year, Rhode Island state Sen. Dawn Euer said of the state legislation authorizing the change:

“As we know, our whole state and Newport especially are deep in an affordable housing crisis, and residential property tax relief is one tool to help address affordability…. Vacation rentals and short-term rentals take away from year-round housing, and while they do provide revenue, they contribute to our city’s housing crisis. Making a distinction between them will give residents the tax relief they need, and encourage property owners to create and maintain the permanent housing we desperately need.”

This arrangement should help stabilize housing in the city, which has long been destabilized by the high number of financially alluring (for property owners) expensive short-term warm-weather or even weekend rentals. But it’s hard to know what the effect on total property-tax revenue for the city might be. It will probably take a year to find out.

In any event, some lessons for other communities will come out of the Newport program, especially those in coastal resort areas.

Chris Powell: What housing emergency?

In Danbury: Clockwise from top left: Main Street Historic District, The Summit at Danbury, Tarrywile Mansion, Praxair Headquarters, Danbury Municipal Airport, Danbury Fair Mall, David Wooster Monument, Western Connecticut State University, and the Danbury Railway Museum

— Wikipedia

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Maybe the recession that has begun will loosen up Connecticut's housing market, but it will take a while even as the poor get poorer. The housing shortage is already making life desperate for many of the poor. But state government doesn't yet consider it an emergency, not even in the face of what seems about to happen in Danbury.

For the two years of the virus epidemic a former hotel building in Danbury has been operated as a shelter for the homeless by a social-service organization based in Stamford, Pacific House. The organization got state financing to purchase the building for use as a shelter but Danbury's zoning board has refused to approve it. The shelter has stayed in operation only because of one of Gov. Ned Lamont's emergency orders arising from the epidemic, but those orders expire Dec. 28.

The former hotel is adjacent to Interstate 84 and few residences are nearby, so the shelter is no more of a nuisance than the hotel was. While it is far from medical and commercial facilities and thus not the most convenient location for the homeless, Pacific House can bring services to them or help them get where they need to go as they work to gain self-sufficiency.

If state government really cared about the poor and troubled, it would pass a law exempting shelters from zoning regulations just as it has exempted group homes for the mentally handicapped.

Danbury lacks any facility that can accommodate all the people now being housed at the former hotel. Most may be out on the street at the end of the month just as the dead of winter sets in. Surely state government can put aside less essential matters until it solves the emergency housing problem.

Crooked guards

Connecticut's Correction Department lately worsened the state's housing problem. It was inadvertent but predictable.

Since prison guards work in tightly confined spaces and were at more risk of contracting COVID 19, the department used federal epidemic emergency money to let them rent hotel rooms so they might avoid infecting their families.

But, the Connecticut Mirror reports, state auditors found that the program was badly abused. Correction Department employees, the Mirror says, "used the program to book hotel rooms during a wedding, to celebrate New Year's Eve, and to live full-time in the hotels with their families. ... Others booked rooms in multiple hotels on the same days, and at least one correction officer used the program while he was on military leave." Some employees used the program to live in hotels for five months or more.

There were rules again this kind of thing but since this was an emergency, no one was hired to enforce them. Some employees who abused the program suffered short suspensions but it seems that no one was fired or prosecuted.

Of course, much federal emergency money has been defrauded throughout the country, just as it was defrauded by the corrupt city government in West Haven, where more than a million dollars was stolen or misdirected by a City Council aide who was also a state representative.

The lesson seems to be that any emergency's first order of business should be to hire extra auditors.

Another murder despite protective order

Another Connecticut woman who had a protective order was murdered the other week, apparently by the former boyfriend she got the order against. Julie Minogue of Milford was battered to death with an ax after her ex had harassed her with hundreds of text messages. An arrest warrant application for the harasser had been pending, left incomplete, for weeks.

The Connecticut Coalition Against Domestic Violence says there have been 12 intimate partner murders in the state so far this year.

The only way to stop them is to require police, prosecutors, and courts to give priority to domestic threats and violence and to impose heavy penalties upon conviction, even for first offenses. Here too state government is always doing many less important things.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

And Hell that way

Lake Waramaug, in Litchfield, Conn., with Mt. Bushnell across the water.Z

“This was a little valley all to myself

In Connecticut’s northern hills: Cornwall was there;

Warren to westward: Waramaug Lake to the south;

And the great Gehenna {hell} sufficient six-score leagues—’’

“From “Death at The Purple Rim,’’ by Hyam Plutzik (1911-1962), a poet who grew up in Connecticut.

Your own tyrants

1814 map showing the location of the Federal Street Church, led by William Ellery Channing. The building was eventually abandoned because of the neighborhood’s density and the congregation moved to the Arlington Street Church (built 1861), below, often called “the Unitarian Vatican.’’

“The worst tyrants are those which establish themselves in our own breasts.”

— William Ellery Channing (1780-1842), Boston-based Unitarian minister and theologian

Reminder

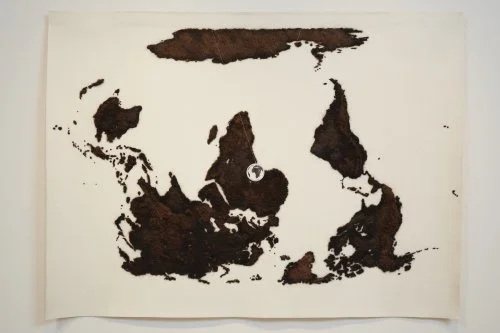

”Global Inversion” (wool felt, human hair and acrylic hair), by Diane Jacobs (America and Jewish), at the Portland (Maine) Museum of Art.

Museum of Science, gaming firm join the metaverse

Inside the Blue Wing of the Boston Museum of Science

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report

The Boston Museum of Science is teaming up with the gaming company Roblox to join the metaverse by launching an immersive online game titled ‘‘Mission: Mars”.

Using data provided by NASA, Mission: Mars will encourage players to navigate engineering challenges around the planet. Some missions will recall science fiction, such as rescuing virtual explorers, but most challenges are inspired by the experiences of real astronauts.

Staff at the museum say that the game will expand beyond just using virtual reality. Mission: Mars will be available for free at schools to encourage teachers to incorporate the game into their teaching. The museum would like to continue to develop programs using Roblox’s platform in an effort to expand access to academic resources.

The Museum of Science’s president, Tim Ritchie, said, “I think you can build and design and use your heart and your mind and your hands, so to speak, by building things and designing things in a digital world. And in fact, it’s a lot less expensive to do so. And you can reach people all over this country and all over the world.”

Tough customers

This is a statue at the Massachusetts State House of the formidable Anne Hutchinson (1591-1643), a Puritan spiritual adviser, religious reformer and a founder of Portsmouth, R.I.

“The clear lesson of New England's history is that when there are not enough suitable men around to run the world, women are perfectly capable of doing so. “

— Wallace Stegner (1909-1993), American novelist, short-story writer and environmentalist

This last season

Covered bridge in Henniker, N.H.

— Photo by Jokermage

”This change of light and how it wakes you with uneasiness

and the shift of wind from the north that rains down ice

might keep you covered for months. You swear this will

be your last season in a place you believe is disappearing.’’

— From “This Last Place,’’ by Maura MacNeil, a Deering, N.H., poet and writing teacher at New England College, in Henniker.

America's culture of cocophany

Paint on a piece of film wrap over a bass speaker playing very loud music.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

America is a noisy place, often painfully so. But many people seem to like that.

The other night, six of us went to a Mexican restaurant in Providence called Dolores. The food was pretty good, though the service was a bit slow because of what appeared to be the staffing shortage that bedevils many restaurants. Always a tough business, but much more so in the Age of COVID.

It was a painful meal for us. The bass-heavy background music made it very arduous to try to hear what people across the table were saying. The next day, our ears still hurt from two hours in the racket.

And yet the place was packed on that Monday evening. You could see customers shouting to each other, but most were smiling. My hunch is that for many people in our culture of cacophony, a noisy place signifies excitement and somehow evokes the happy idea that they’re where the action is – that they’re not missing out.

Since the last two generations have grown up amidst increasing noise – rock music, etc. – that’s more and more difficult to escape – perhaps quiet makes them nervous.

Meanwhile, the gasoline-powered leaf blowers shriek from dawn to dusk, polluting the air and driving away the birds and indeed many walkers who try to avoid the racket, the fumes and the grit by finding other routes. And drugstores have automated bad music.

‘Fragile systems of beauty’

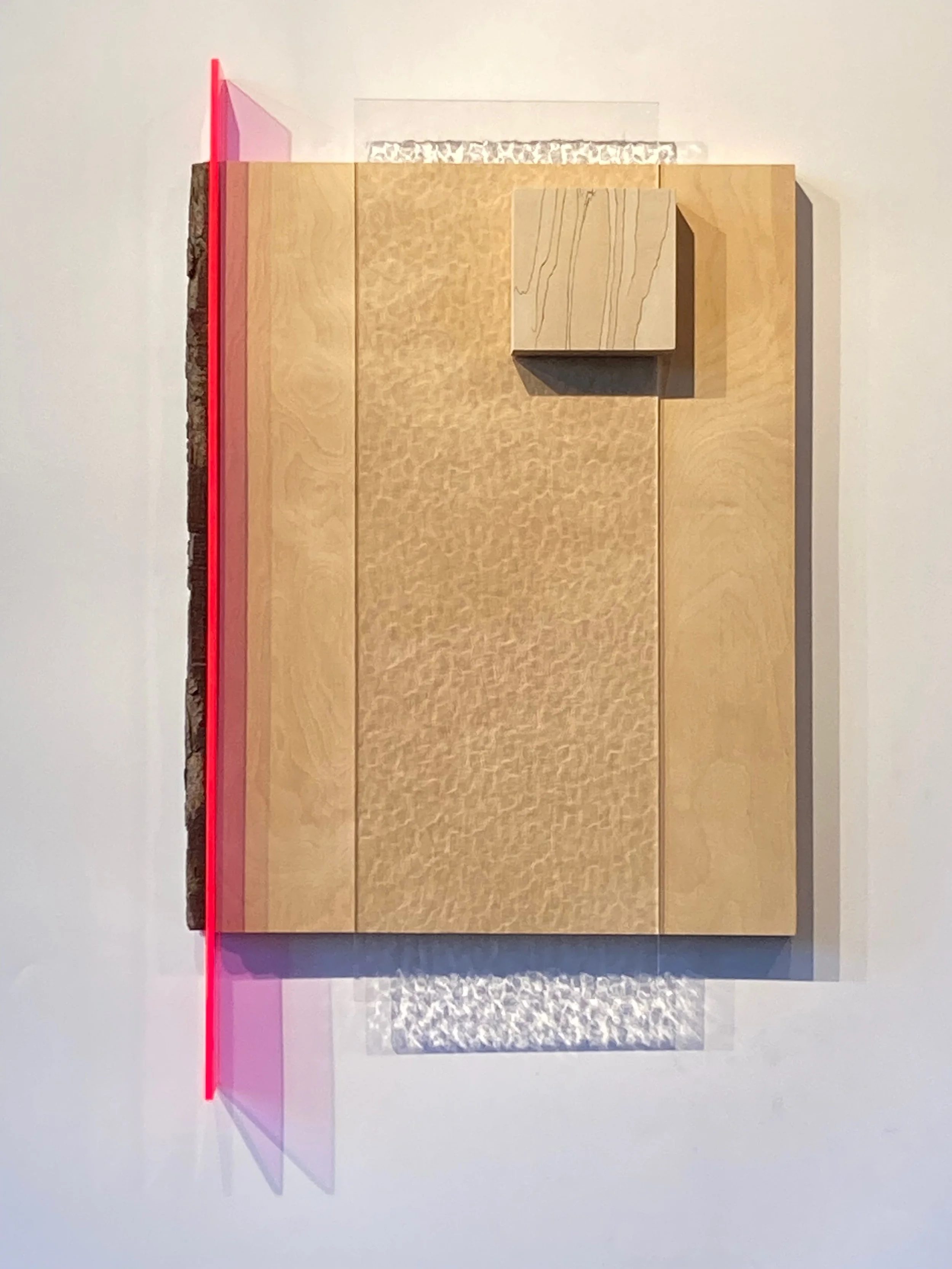

“Breakthrough” (sculptural collage, mixed media including wood panels, tree bark, acryli and plexiglass), by Boston area artist Luanne Witkowski, in her show “Clarity,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, March 1-April 2.

The gallery says:

Ms. Witkowski “uses both found natural materials and fabricated cast-offs and scraps, focusing on composition, recurrent pattern, minimalist form, and color to create an artistic response to the fragile systems of beauty and the raw power that exist in both the natural world and urban landscapes. For the artist, this response is accessible through the contemplative creative process of perception, when we allow ourselves to relax into our senses. Witkowski’s daily routines - walking through forests, parks and countryside of wildlife, flora and fauna followed by engagement with city streets, glass and artificial light - interweave the interaction and juxtaposition of her various materials. In doing so, she recalls the shared experiences grounded in each of us: creating a perceptual and spiritual relationship for recognition of and solace for the self. This approach to the identification of the individual with landscape and environment is enlarged by a desire to discover and connect with the particular indwelling essence or energy of clarity.’’

Llewellyn King: New hope arises for fusion energy after years of broken hearts, but….

The target chamber of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s National Ignition Facility in California where 192 laser beams delivered more than 2 million joules of ultraviolet energy to a tiny fuel pellet to create fusion ignition on Dec. 5, 2022.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

While the rafters are ringing with praise for the nuclear-fusion breakthrough at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), let me inject a sour note: This isn’t the beginning of cheap, safe, non-polluting electricity.

It is a scientific milestone, not an electricity one. Science tantalizes but it also deceives. Often the mission turns out not to be the one for which years of scientific research was aiming.

I would remind the world that science stirred great hope futilely with the idea of superconductivity at ambient temperatures, after some laboratory success.

The history of fusion itself is a clear illustration of expectations dashed, revived, resurrected, and dashed again. Now there is some hope with a stunning lab success: the first future experiment with “gain,” meaning more energy came out of the experiment than went into it.

Fusion has been the goal, the light at the end of the tunnel for nuclear researchers for over 60 years. In that time there have been false prophets, failed attempts, elaborate claims, and just hard slog.

That hard slog has shown what is possible: More power has been achieved in a fusion experiment for a fraction of a second. That is a huge success but it isn’t limitless electricity, as some have heralded.

Fission — which makes possible our power reactors and warships — is the splitting of the atom to release heat that is converted, via steam, into electricity.

Fusion, beguiling fusion, seeks to do what happens in stars and the sun — the fusing of two atoms together to produce heat, which, in a reactor, would be used to create steam and turn turbines, making electricity.

Governments and researchers have salivated over the possibility of fusion for decades and it has been well-funded worldwide, compared with other energy sources.

Getting fusion temperatures at or above those on the sun must be achieved to fuse two deuterium atoms together. Deuterium, also called “heavy hydrogen,” is an isotope of hydrogen. If you can do that and sustain the reaction for months and years, you can then design a reactor that would create steam, or use some other fluid, to turn a turbine.

There are two approaches scientists have used to get fusion. One is inertial fusion, used in the breakthrough at the National Ignition Facility at LLNL, near San Francisco, which involves hitting a pellet with a concentrated beam of energy: The lab used 192 super-powerful lasers to get fusion.

In the early 1980s, I spent time at LLNL and watched an experiment to hit the target with big accelerators. There were, as I recall, eight of them the size of cars. The research scientist showing me the facility said that accelerators the size of locomotives were needed to continue the experiments.

The other approach to get fusion is the tokamak, a Russian word, which describes a doughnut-shaped machine where a plasma is superheated with electricity, and the whole thing is held together in powerful magnetic fields. This is the technology being pursued internationally by a 35-nation consortium at the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), in Cadarache, southern France.

This tokamak, or toroidal approach, is the one most favored in the community to succeed eventually as a source of heat to make electricity.

Also, a lot of solid work on fusion has been done at the General Atomics facility in La Jolla, Calif., and at research facilities across the United States and around the world. I visited the General Atomics site many times, crawled inside the machine, and wondered at the math and science that have gone into the pursuit of fusion.

Back in the 197os, physicist Keeve “Kip” Siegel believed that he could achieve fusion with simple, off-the-shelf optical lasers. He died of a stroke in March 1975, while testifying before the Joint Congressional Committee on Atomic Energy in defense of his laser fusion research.

Bob Guccione, founder and publisher of Penthouse, hooked up with a former member of Congress from Washington State, Mike McCormack, and together they sought to promote fusion.

Two eminent scientists, Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann, thought they had a breakthrough with so-called cold fusion. But this chemical process hasn’t panned out.

When I was looking at that fusion experiment at LLNL in the early 1980s, the researcher showed me on his computer a wonderful new way of communicating with other scientists around the world. I thought it was just a Telex on steroids and went back to questions about fusion, despite my guide's enthusiasm for the new communications system.

It was the Internet, and I missed the big story — as big as a story can get — to keep reporting on fusion. You can see why I may be soured.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C. He’s a long-time journalist, speaker and consultant in the energy sector.

Web site: whchronicle.com

‘I’m spoiled’

— Photo by Niranjan Arminius

Start of a game of water polo on Main Street, Saxtons River, after the July 4th parade in 2013. The game is played by volunteer firefighters with fire hoses, trying to spray the ball down the street to a goal. Looking west at the Saxtons River Historical Society (a former Congregational church).

“I’m spoiled by the lack of traffic, the beauty all around me, the night sky, the wildlife, and having more space and time to think and be creative.’’

— Julie Moir Messervy, Saxtons River, Vt.-based landscape architect, in Vermont Life magazine. Saxtons River is a village in the town of Rockingham.

Movements in lives

“Dance of the Titled Mothers” (acrylic and natural dyes and pigments on burlap and handwoven cotton cloth) by Boston-based artist Stephen Hamilton, in his show “Passages: Stephen Hamilton,’’ at LaiSun Keane Gallery, Boston, through Dec. 31.

— Photo courtesy of LaiSun Keane Gallery

Mr. Hamilton incorporates both Western and African techniques in his work. He says this show "examines the movement between adolescence and adulthood, adulthood and elderhood, as well as life, death, and rebirth in African and African-American folklore and philosophy." For more information, please visit here.

George McCully: We need to battle AI robotization

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Every reader of this journal is being affected by the highly exceptional historical phenomenon we are all experiencing: an age of total transformation, of paradigm-shifts in virtually every field of human endeavor. Our own field—postsecondary education and training—is just one among all the others. Younger colleagues, though they may not like it, are experiencing this as a given and generally constructive condition, building their future theaters of operations. Senior colleagues raised and entering the profession in the 20th Century paradigm of “higher education,” experience current transformations as disruptive—disintegrative and destructive of their originally sought-for and later accustomed professional world. Students seeking credentials for future jobs are confused and problematically challenged.

It helps to understand all this turmoil as an inexorable historical process. This article will describe that process, and then address how we individually, and organizations like NEBHE, might best deal with it.

We happen to be living in a very rare kind of period in Western history, in which everything is being radically transformed at once. Paradigm-shifts in particular fields happen frequently, but when all fields are in paradigm-shifts simultaneously, it is an Age of Paradigm Shifts. This has happened only three times in Western history, about a thousand years apart—first with the rise of Classical Civilization in ancient Greece; second with the fall of Rome and the rise of medieval Christianity; and third in the “early modern” period—when the Renaissance of Classicism, the Reformation of Christianity, the Scientific Revolution, the Age of Discovery, the rise of nation states, secularization and the Enlightenment, cumulatively replaced medieval civilization and gave birth to “modern” history in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Modernity, however, is now unraveling, in a transformation with significant unique features.

First and most noticeable is its speed, occurring in a matter of decades (since circa 1990) rather than centuries. The acceleration of change in history, driven by technology’s increasing pace and power, has been going on for centuries—perhaps first noticed by Machiavelli in the Renaissance. Today, the driving transformational force is the rapidly accelerating innovations in digital and internet technology, in particular, increasingly autonomous Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Second, for the first time our technology is increasingly acknowledged to be running ahead of human control; it is becoming autonomous and self-propelled, and we are already struggling to catch up with it.

Third, whereas the first three transformations were intended by human agents, for the first time now, driven by technological advances, we have no clue as to where the technology is headed—what will be the dénouement or if that is even possible.

And fourth, under these conditions of constant change both internally and all around us, strategic planning in any traditional sense is impossible because there are no solid handles we can grasp and hold onto as collaborators or guides into the future. We are adrift in an unprecedently tumultuous sea of change.

For people in post-secondary education and training, this critical situation is especially agonizing because we are in society at various thresholds of adulthood, where personal and professional futures are crucially chosen and determined. We have extraordinarily heavy responsibility for the futures of individuals, of society, of humanity and of our planet—precisely when we have inadequate competence, coordination and self-confidence. We are where humans will address the innovations and disruptions critical to the future, where strategic knowledge and intelligence will be most needed, and where historical understanding will therefore be crucial.

Let us first acknowledge that each, and all, of our jobs sooner or later, can and probably will be robotized by AI. Its technical capacity already exists, noted by many journalists and scholars, for thinking and writing (publicly available GPT-3, and next year GPT-4), visual and musical arts, interactive conversations, cerebral games (chess, Go, et al.) and other problem-solving activities, at quality levels equal to and frequently excelling human-generated work. Significant technological advances are happening almost weekly, and AI nowadays develops these autonomously, written in code it developed for its own machine-learning use. Its aims are not excellence, truth or other value-intensive products, but common-denominator performances adequate to compete commercially with works created by humans and indistinguishable (by humans—though software is being developed intended do this) from them, produced at blinding speed. Suddenly there could appear countless new “Bach” fugues, novels in Hemingway’s style, etchings by Rembrandt, news articles and editorials or academic work—all mass-produced by machines.

Administrative functions—numerary, literary, interactive, decision-making, etc.—will be widely available to ordinary individuals and institutions. What will remain for which humans are needed to do, at prices that yield living wages, is a real question already being considered hypothetically.

Speed bumps helping to shield us from faster robotization are (temporarily at least) the availability of sufficient capitalization, and the time required for dissemination. Here, the fact that we work much more slowly than AI is a temporary but ultimately self-defeating blessing. The driving incentive for takeover is the robots’ greater cost-effectiveness. In the long run, robots work more cheaply and much faster than humans, outweighing losses of quality in performance.

For individuals, our best defense against robotic takeover is for each of us to identify and enhance whatever aspects of our jobs that humans can still do best, which means that we should all start redefining our work in humanistic and value-intensive directions, so that when robotization comes knocking, decision-makers will go for the low-hanging fruit, allowing the easiest transitions first, leaving some margins of continued freedom for humans to continue doing their jobs.

A clear possibility, and I believe necessity, for postsecondary education and training lies in that distinction, extending from individuals’ lives and work to institutions and organizations like NEBHE and their instruments such as this journal. The rise of machine learning (AI) is a wedge, compelling us to cease referring to all post-secondary teaching and learning as “higher education.” There is nothing “higher” about robotic training and commercial credentialing for short-term “gig economy” job markets. Let us therefore first define our terms more carefully and precisely.

“Education,” as in “liberal education,” traditionally means “self-development”; “training” customarily means “knowledge and skills development.” The two are clearly distinct, but not separate except in extreme cases; when mixed, the covering designation depends on which is primary and intentional in each particular case.

In other words, our education helps define who we are; our training helps define what we are—doctor, lawyer, software engineer, farmer, truckdriver, manufacturer, etc. Who we are is an essential and inescapable part of all of our lives that’s always with us; what we are is optional—what we chose to do and be at given times of our lives.

Education is intrinsically humanistic and value-intensive, therefore most appropriately (but not necessarily) taught and learned between humans; training can be well-taught by AI, imparting knowledge and skills from robots to humans. Ideally, to repeat for emphasis, both education and training usually involve each other in varying proportions—when education includes knowledge and skills development, and training is accompanied by values. But these days especially, we should be careful not to confuse them.

For individuals, certainly education and possibly training are continuing lifelong pursuits. AI will take over training most easily and first, especially as rapid changes and transformations overtake every field, already producing a so-called “gig” economy in which work in any given capacity increasingly becomes temporary, more specialized and variegated, affecting the lives and plans of young employees today. Rapid turnover requires rapid increases in training, certifying, credentialing programs and institutions. Increasing demand for it has evoked many new forms of institutionalization—e.g., online and for-profit in addition to traditional postsecondary colleges and universities—as well as an online smorgasbord of credentials for personal subscriptions. For all of these, AI offers optimal procedures and curricula, increasingly the only way to keep up with exploding demand; thus, the proliferation of kinds of institutions, programs, curricula, courses and credentials is sure to continue.

The need for education will also increase, so the means of delivery and content in such a disturbed environment will require extraordinarily innovative creativity, resilience and agile adaptability among educators. The highest priority will have to be keeping up with the transformations—figuring out how best to insert the cultivation of humane values, best accomplished between human teachers (scholars, professors, practitioners) and learners, and provided by educational institutions and individuals, into the many new forms of training. Ensuring that this happens will be a major responsibility of today’s educational infrastructure and personnel, because AI does not, and does not have to, care about values. Will individual learners care? Not necessarily—for consumers of credentials, personal and even professional values apart from their commercial value are not a top priority. Whether employers will care about them is a major issue for concern by educators.

Here, the paradigm-shift in post-secondary education and training arises for attention by umbrella organizations like, for example, NEBHE and this journal. When NEBHE was founded, in 1955, the dominant paradigm in post-secondary education was referred to simply as “higher” education” (the “HE” in those acronyms)—residing in liberal arts colleges (including community colleges) and universities. The New England governors, realizing that the future prosperity of our region would be heavily dependent on “higher” education, committed their states to the shared pursuit of academic excellence in which New England was arguably the national leader.

That simple paradigm, however, has been superseded in practice. Today, the much greater variety of institutional forms and procedures, much more heavily reliant on rapidly developing technology, and the recognized need for broader inclusion of previously neglected and disadvantaged populations, calls for reconceptualization and rewording, reflecting the broader new reality of post-secondary, lifelong, continuing education and training.

New England is no longer the generally acknowledged national leader in this proliferation; the paradigm-shifting is a nationwide phenomenon. Nonetheless, though the rationale for a New England regional umbrella organization for both educational and training infrastructure has been transformed, it persists. Now it is needed to help the two branches of post-secondary human and skills development work in mutually reinforcing ways, despite the challenges—which are accelerating and growing—for both branches. Lifelong continuing education and training will be enriched, strengthened and refined by their complementary collaboration for all demographic constituencies.

How this might happen among an increasing variety of institutions still needs to be worked out in this highly fluid and dynamic environment. That is the urgent challenging mission and responsibility of the umbrella organizations. At the ground-level, individual professionals need to be reassessing their jobs defensively in humanistic directions, for which they will be fortified with a strategic sense of mission as a crucial element in the comprehensive infrastructure. Beyond that, coordinated organization will help form multiple alliances among institutions in a united front against encroaching AI robotization. This may be the only pathway for retaining roles and responsibilities by humans into the future.

George McCully is a historian, former professor and faculty dean at higher education institutions in the Northeast, professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy.

Liz Szabo: Why the lack of pediatric beds? They don’t pay well

— Photo by Robert Lawton

Hasbro Children’s Hospital, in Providence

“We have doctors who are cleaning beds so we can get children into them faster.’’

—Megan Ranney, M.D,. deputy dean at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

The dire shortage of pediatric hospital beds plaguing the nation this fall is a byproduct of financial decisions made by hospitals over the past decade, as they shuttered children’s wards, which often operate in the red, and expanded the number of beds available for more profitable endeavors like joint replacements and cancer care.

To cope with the flood of young patients sickened by a sweeping convergence of nasty bugs — especially respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, and coronavirus — medical centers nationwide have deployed triage tents, delayed elective surgeries, and transferred critically ill children out of state.

A major factor in the bed shortage is a years-long trend among hospitals of eliminating pediatric units, which tend to be less profitable than adult units, said Mark Wietecha, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. Hospitals optimize revenue by striving to keep their beds 100 percent full — and filled with patients whose conditions command generous insurance reimbursements.

“It really has to do with dollars,” said Dr. Scott Krugman, vice chairman of pediatrics at the Herman and Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore. “Hospitals rely on high-volume, high-reimbursement procedures from good payers to make money. There’s no incentive for hospitals to provide money-losing services.”

The number of pediatric inpatient units in hospitals fell 19% from 2008 to 2018, according to a study published in 2021 in the journal Pediatrics. Just this year, hospitals have closed pediatric units in Boston and Springfield, Mass.; Richmond, Va., and Tulsa, Okla.

The current surge in dangerous respiratory illnesses among children is yet another example of how COVID-19 has upended the health-care system. The lockdowns and isolation that marked the first years of the pandemic left kids largely unexposed — and still vulnerable — to viruses other than covid for two winters, and doctors are now essentially treating multiple years’ worth of respiratory ailments.

The pandemic also accelerated changes in the health-care industry that have left many communities with fewer hospital beds available for children who are acutely ill, along with fewer doctors and nurses to care for them.

When intensive-care units were flooded with older COVID patients in 2020, some hospitals began using children’s beds to treat adults. Many of those pediatric beds haven’t been restored, said Dr. Daniel Rauch, chairman of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on hospital care.

In addition, the relentless pace of the pandemic has spurred more than 230,000 health-care providers — including doctors, nurses, and physician assistants — to quit. Before the pandemic, about 10% of nurses left their jobs every year; the rate has risen to about 20%, Wietecha said. He estimates that pediatric hospitals are unable to maintain as many as 10% of their beds because of staffing shortages.

“There is just not enough space for all the kids who need beds,” said Dr. Megan Ranney, who works in several emergency departments in Providence, including Hasbro Children’s Hospital. The number of children seeking emergency care in recent weeks was 25% higher than the hospital’s previous record.

“We have doctors who are cleaning beds so we can get children into them faster,” said Ranney, a deputy dean at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

There’s not great money in treating kids. About 40% of U.S. children are covered by Medicaid, a joint federal-state program for low-income patients and people with disabilities. Base Medicaid rates are typically more than 20% below those paid by Medicare, the government insurance program for older adults, and are even lower when compared with private insurance. While specialty care for a range of common adult procedures, from knee and hip replacements to heart surgeries and cancer treatments, generates major profits for medical centers, hospitals complain they typically lose money on inpatient pediatric care.

When Tufts Children’s Hospital closed 41 pediatric beds this summer, hospital officials assured residents that young patients could receive care at nearby Boston Children’s Hospital. Now, Boston Children’s is delaying some elective surgeries to make room for kids who are acutely ill.

Rauch noted that children’s hospitals, which specialize in treating rare and serious conditions such as pediatric cancer, cystic fibrosis, and heart defects, simply aren’t designed to handle this season’s crush of kids acutely ill with respiratory bugs.

Even before the autumn’s viral trifecta, pediatric units were straining to absorb rising numbers of young people in acute mental distress. Stories abound of children in mental crises being marooned for weeks in emergency departments while awaiting transfer to a pediatric psychiatric unit. On a good day, Ranney said, 20% of pediatric emergency room beds at Hasbro Children’s Hospital are occupied by children experiencing mental health issues.

In hopes of adding pediatric capacity, the American Academy of Pediatrics joined the Children’s Hospital Association last month in calling on the White House to declare a national emergency due to child respiratory infections and provide additional resources to help cover the costs of care. The Biden administration has said that the flexibility hospital systems and providers have been given during the pandemic to sidestep certain staffing requirements also applies to RSV and flu.

Doernbecher Children’s Hospital at Oregon Health & Science University has shifted to “crisis standards of care,” enabling intensive care nurses to treat more patients than they’re usually assigned. Hospitals in Atlanta, Pittsburgh, and Aurora, Colorado, meanwhile, have resorted to treating young patients in overflow tents in parking lots.

Dr. Alex Kon, a pediatric critical-care physician at Community Medical Center in Missoula, Montana, said providers there have made plans to care for older kids in the adult intensive care unit, and to divert ambulances to other facilities when necessary. With only three pediatric ICUs in the state, that means young patients may be flown as far as Seattle or Spokane, Washington, or Idaho.

Hollis Lillard took her 1-year-old son, Calder, to an Army hospital in Northern Virginia last month after he experienced several days of fever, coughing, and labored breathing. They spent seven anguished hours in the emergency room before the hospital found an open bed and transferred them by ambulance to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Maryland.

With proper therapy and instructions for home care, Calder’s virus was readily treatable: He recovered after he was given oxygen and treated with steroids, which fight inflammation, and albuterol, which counteracts bronchospasms. He was discharged the next day.

Although hospitalizations for RSV are falling, rates remain well above the norm for this time of year. And hospitals may not get much relief.

People can be infected with RSV more than once a year, and Krugman worries about a resurgence in the months to come. Because of the coronavirus, which competes with other viruses, “the usual seasonal pattern of viruses has gone out the window,” he said.

Like RSV, influenza arrived early this season. Both viruses usually peak around January. Three strains of flu are circulating and have caused an estimated 8.7 million illnesses, 78,000 hospitalizations, and 4,500 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Krugman doubts the health-care industry will learn any quick lessons from the current crisis. “Unless there is a radical change in how we pay for pediatric hospital care,” Krugman said, “the bed shortage is only going to get worse.”

Liz Szabo is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

The power lines around us

“Rugged Road and Power Lines” (welded steel, rugs, installations together), by Boston-based Andy Zimmermann, in his show “Rugged Road,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, Dec. 14-Jan. 290.

The gallery says:

“Two ambitious installations, ‘Rugged Road’ and ‘Power Lines,’ combined to suggest a landscape, anchor the show, which also includes smaller-scale welded steel sculptures and digital collages.

The titular installation, ‘Rugged Road,’ features a collection of rugs suspended in a steel scaffolding constructed to form a composition evocative of a flower or an explosion. Collected from a range of sources, including yard sales, flea markets, thrift stores and ebay, some are new and made to look used while others are truly worn, and come from as far afield as Morocco, Turkey, and Afghanistan. The rugs suggest a wide range of human conditions, from a symbol of great opulence, to a wrapper carried by a refugee family, from a piece of trash, to a magic flying carpet.

“The ‘Rugged Road’ construction is situated within the surrounding installation entitled ‘Power Lines.’ These welded steel structures clearly refer to high-tension electric lines and their support towers. Placement and forced perspective describe a rugged landscape, with symbolic and political overtones.

“The re-purposing of materials is an underlying theme for Zimmermann. Most of the rugs are used, providing archeological evidence of decades of life in a household. Much of the steel scaffolding has been used by the artist in previous installations. The signs of use and wear evident in these materials become part of the content in their present iteration. This concept is further explored in the digital collages on display. They include images of some Zimmermann’s earlier artworks, elements of autobiography to be unearthed.’’

Another triumph for New England biotech?

The Philip A. Sharp Building, in Cambridge, which houses the headquarters of Biogen

— Photo by Astrophobe

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’ in GoLocal24.com

This is another “we’ll see’’ situation that gives hope.

Japan’s Eisai Co. and Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen Inc. have developed a drug, called lecanemab, that destroys the amyloid protein plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Patients in the drug trial have had a slowing of symptoms. Researchers have much to learn about the drug’s benefits, side-effects and cost, but the apparent breakthrough may the most hopeful sign yet that a highly effective treatment of this terrible dementia might be in the offing.

Hit this link for The New England Journal of Medicine article on this.

Further, since the buildup of abnormal proteins in the brain is also seen in such (usually) old-age-related ailments as Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease, lecanemab may have wider applications than just for Alzheimer’s as the population continues to age.

This could be another triumph for New England’s bio-tech industry, but it may take many months to find out for sure.

‘Like profanation’

— Photo by Christoph Geisler

I had for my winter evening walk—

No one at all with whom to talk,

But I had the cottages in a row

Up to their shining eyes in snow.

And I thought I had the folk within:

I had the sound of a violin;

I had a glimpse through curtain laces

Of youthful forms and youthful faces.

I had such company outward bound.

I went till there were no cottages found.

I turned and repented, but coming back

I saw no window but that was black.

Over the snow my creaking feet

Disturbed the slumbering village street

Like profanation, by your leave,

At ten o’clock of a winter eve.

— “Good Hours,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)