Chris Powell: The Pequots’ casino privilege and a history lesson

The gigantic Foxwoods casino and resort complex, in the hills of eastern Connecticut. It’s owned by people at least partly descended from members of the Pequot tribe living in the area when the English move into it in the 17th Century.

— Photo by Elfenbeinturm

Engraving depicting the attack on the Pequot fort at Mystic on May 26, 1637, from John Underhill’s Newes from America, London, 1638

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Student performance, and even attendance, in Connecticut's public schools are crashing, but not to worry. With Gov. Ned Lamont presiding, the state Education Department and the state's five officially recognized Indian tribes announced the other day that they will create a model curriculum in Native American studies. The curriculum will be offered to the schools, where, if it is used, may crowd out basic academic teaching, as "social-emotional learning" already is doing.

Indeed, the Native American studies curriculum may be especially useful for distracting from the crash of public education. Everyone in authority can keep looking busy while carefully avoiding relevance to the disaster.

Of course if students ever managed to read at grade level, it would be great to have a more accurate and comprehensive account of the country's history, overcoming what kids pick up from cowboys-and-Indians theater. But such an account is not likely to emerge from anything assembled by the Education Department and the Indian tribes. The curriculum probably will be constructed to rationalize perpetual grievance, victimhood and privilege. After all, legislation to create the curriculum was proposed by state Sen. Cathy Osten (D-Sprague, or maybe more accurately, D-Foxwoods).

A news report about the curriculum suggested that the history of the Indian tribes and the European settlers who founded Connecticut is such a sensitive subject that it will be uncomfortable to relate, apparently because some think that assigning guilt will be necessary.

Nonsense. For the Connecticut history to be taught here is only the history of mankind -- tribalism and the struggle to overcome it, with the peculiarly American denouement whereby, as society began to overcome it, tribalism was seen as an excellent mechanism for delivering political patronage and so was restored and embedded in law for perpetuity.

In early Connecticut there were more than two tribes, the Europeans and Indians. There were multiple Indian tribes with shifting alliances, and the peace was broken as much as by the Indians as the Europeans. The Pequots, whose remote descendants today claim entitlement to perpetual victimhood because of the tribe's near-extermination by English colonists in a battle in Mystic in 1637, oppressed other Indian tribes and so were hated by them. The name "Pequot" meant "destroyer."

So the Mohegans, Narragansetts and Niantics joined the Europeans to destroy the Pequots themselves -- men, women and children alike, an atrocity far greater than the atrocities that had been inflicted by the Pequots on their enemies, atrocities that had prompted the war.

The Pequot chief Sassacus, who was away with a raiding party at the time of the Mystic massacre, fled to the west and was killed not by the English but by the Mohawks, who sent his severed head and hands to the colonists in Hartford as an offering of friendship.

Of course, the extermination of most of the Pequots was not quickly followed by an age of equality, light and happy assimilation. Indian lands were bought or expropriated, more easily because the Indians did not share the Europeans' concept of private property. Hewing to its old ways, Indian culture faded under the burden of discrimination.

But over the decades intermarriage and vast new immigration to what became the United States hastened assimilation of Connecticut's ethnicities, and eventually, though only a half century ago, full equality under the law, if not quite in actual living conditions, was established. Now the descendants of the old tribes and the various ethnicities were trying to make a living more or less in the same culture.

Whereupon government, in its endless thirst for revenue, contrived to dress up casino gambling as a form of ethnic reparations for ancient wrongs that lacked surviving victims. In southeastern Connecticut certain people who lived in raised ranches and worked at Electric Boat like everybody else suddenly could claim to be oppressed on behalf of their distant ancestors. In the name of this ancestry state government gave them a casino duopoly and thus perpetual wealth to be inherited by their descendants at the expense of the rest of society.

Almost as quickly as it had arrived in Connecticut, equality under the law was undone. As a political matter this new ethnic privilege will require perpetuating the false impression of victimhood. Hence the Education Department's new curriculum.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

‘A world without boundaries’

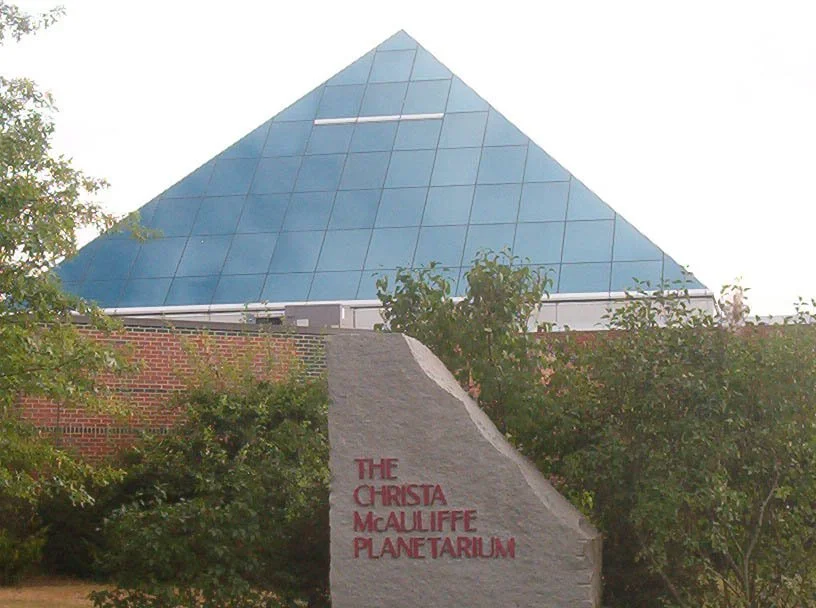

Christa McAuliffe

The McAuliffe-Shepard Discovery Center, in Concord, N.H. The Shepard refers to Alan Shepard (1923-1998), a Derry, N.H., native and early astronaut.

— Photo by Karmafist

"You have to dream. We all have to dream. Dreaming is okay. Imagine me teaching from space, all over the world, touching so many people's lives. That's a teacher's dream! I have a vision of the world as a global village, a world without boundaries. Imagine a history teacher making history!"

— Christa Auliffe (born 1948), the Concord (N.H.) High School history teacher who was one of the seven astronauts killed in the breakup of the Challenger space shuttle on Jan. 28, 1986.

Ginette Saimprevil: The long road to education equality in Boston

At 46 Joy St., Boston, the Abiel Smith School, was founded in 1835 and is the oldest public school in the U.S. built for the sole purpose of educating African-American children. It houses the Museum of African American History.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Boston has had an extraordinarily long and tumultuous history as a fulcrum of the fight for the equal education of Black people.

Black Bostonians began petitioning the Massachusetts legislature for greater access to the public school system in 1787. In 1835, the Abiel Smith School opened—the first building erected for the sole purpose of housing a Black public school. However, conditions in this underfunded, segregated school were below standard, and the Black community continued to campaign for equal-education opportunities. While public school segregation was officially outlawed in 1855, de facto segregation continued to be the reality in Boston.

In 1965, the legislature passed the Racial Imbalance Act, which outlawed segregation in public schools and, most significantly, defined segregated schools as those with a student body comprised of more than 50 percent of a particular racial group. Yet despite this ruling, Boston School Committee members refused to implement plans to integrate the city’s schools, and the relentless struggle for equal education continued.

In 1974, a federal court-ordered busing plan to end school segregation in Boston resulted in an eruption of protests and violence in the streets, as well as death threats against the judge in the case. Even innocent children being bussed were attacked. Despite the continuation of busing for more than a decade, white flight and a later decision to allow children in residentially segregated areas to attend neighborhood schools resulted in resegregation of many of Boston’s schools. By the 2017-18 school year, more than half of Boston Public Schools were profoundly segregated—even more than in 1965, according to a 2018 report by The Boston Globe. This situation persists to this day.

Boston’s segregated schools, with largely Black and Latinx students, tend to have a higher student-to-teacher ratio as well as older textbooks, lower quality facilities, fewer school counselors per student and other inequalities. This inevitably means that these students will face greater difficulties when it comes to gaining admission to college, completing their degrees and embarking on careers.

Secret sauce

At Bottom Line (BL), we seek to level the playing field by providing students with ongoing in-person advising from their senior year in high school through college graduation. Our trained, professional advisers deliver intensive, relationship-based, one-on-one advising, and they partner with students to select and gain admission to a college that is the best possible fit—academically, financially and culturally.

Our access advisers support high school seniors, based on their individual needs, in navigating the college application process using our LEAAD curriculum:

List: generating a list of colleges suited to students’ academic and financial situations.

Essay: brainstorm, writing and editing essays.

Applications: completing college applications.

Affordability: securing financial aid.

Decision: making a college choice.

Advisers and students review students’ options to select a college that best meets academic, financial and personal needs, with students receiving transition-to-college programming over the summer before their first college year.

The “secret sauce” in the Bottom Line approach is the holistic support—considering the whole student and building authentic relationships through our hybrid model. Our advisers conduct some in person meetings and provide remote support via video, phone and text communication.

In the college-access program, students meet with their advisers about 10 times a year. In the success program in college, students are paired with a success adviser who works with them one on one. Advisers offer regular support in the four areas most likely to cause a student to drop out of college: Degree, Employability, Affordability and Life, or DEAL.

This comprehensive support is provided for up to six years or until a student graduates. Our career-connections team and advisors provide coaching and support to help students/recent graduates build their social and career capital to launch mobilizing careers. Support includes mock interviewing, resume-writing workshops, help securing job shadows and internships, and networking events to prepare students for the workforce.

This work has a significant impact on our students and communities we serve. On average, our students earn nearly double their family income in their first job out of college. Our individualized college access, success and career connections support to students also results in a historic six-year graduation rate of 76 percent (more than double the national average).

Bottom Line’s model is recognized for its rigorous, externally validated proof-of-impact on college enrollment, persistence and graduation. An independent research report on “The Bottom Line on College Advising: Large Increases in Degree Attainment” confirms the impact of current BL programs and the notable potential for expansion. Researchers found that compared to the controlled group, Bottom Line students are 23 percent more likely to graduate from college. The researchers also added, “While the observed degree effects are quite consistent across different types of students, the fact that BL primarily serves students of color furthermore suggests that substantial expansion of the BL model could contribute to increased racial equity and mobility in the U.S.”

The estimated impact of advising on bachelor’s degree attainment is roughly as large as the (conditional on aptitude) gap in degree attainment between children from families in the first and fourth quartile of the income distribution.

I know from my personal as well as professional experience that the Bottom Line model works. My family emigrated from Haiti when I was 10. While my parents instilled in me a tradition of diligence and perseverance, they had no experience with higher education and were unable to help me navigate college-admissions and financial-aid processes. Fortunately, I was introduced to the BL program when I was a high school junior, and my adviser helped me find my way to a full tuition scholarship at Bowdoin College and a fulfilling career helping other students succeed.

Recently, our organization received a $15 million grant from philanthropist MacKenzie Scott. This grant will let us accelerate implementation of our strategic plan. This plan partly includes strategies to increase the number of students in Boston, New York City and Chicago, because we know there is a need for educational equity across the nation. The goal is to directly serve 20,000 students as well as reach 400,000 indirectly.

The Abiel Smith School, the oldest public school in the U.S. built for the sole purpose of educating African American children, now houses the exhibition galleries of the Museum of African American History. The very walls of this historic building are dedicated to telling the story of the Boston abolitionist movement and equal education. It is an inspiring place to reflect on the role of education at the core of equality and the continuum of persistence and progress in Boston’s Black community. It is a centuries old story that we hope to play a role in by ensuring that more students of color attain their college degrees.

Ginette Saimprevil is executive director of Bottom Line Massachusetts.

Cold-weather creatures

“Snow Crows” ( monoprint), by Susan Amons, in the group show with Lisa Houck and Richard Remsen entitled “Managerie a Trois,’’ at Cove Street Arts, Portland, Maine, through Jan. 21.

— Photo courtesy Cove Street Arts.

The gallery says the show presents animal-themed artwork focusing on creatures often associated with winter. For more information, please visit here.

Main Street in downtown Biddeford

— Photo by Lookinforahome

Europeans first settled in what became Biddeford, which had been well-populated by Native Americans, in 1616. In the 19th Century, Biddeford became a prosperous industrial center, with granite quarries and brickyards and lumber, grain and textile mills. In recent years, some of the old mills have been converted into retail stores, art studios, cultural-event spaces and upscale housing.

Biddeford hosts the University of New England.

Some comforting yarns

“Stock,’’ (oil on linen), by Cindy Rizza, in her show “Cindy Rizza: Habitats,” at the Rochester (N.H.) Museum of Fine Arts through Jan. 6.

— Photo courtesy Rochester Museum of Fine Arts.

The museum says:

The museum says the show features comforting oil paintings of familiar domestic items. Her paintings "delicately [render] everyday domestic objects we use to create a sense of security; their utilitarian and decorative functions act to create a sanctuary. Her work simultaneously brings a sense of warm nostalgia and chilling loss.’’

The museum is open Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. — 6 p.m. The Rochester Museum of Fine Arts is located at 150 Wakefield Street, Rochester, NH. For more information, please visit here.

The Cocheco River provided power for Rochester’s early factories.

—Photo by AlexiusHoratius

Linda Gasparello: Postcards from Greece -- joyous and tragic

Distomo, Greece — site of great beauty and great barbarity

I know -- through my education and experience -- the Latin phrase, “In vino veritas.” But until recently, I didn’t know the Latins lifted it from Alceus of Mytilene, a 6th-Century BC lyric poet from the Greek island of Lesbos, who said, “Wine, window into a man.”

Alceus was a contemporary of Sappho, known as the “Tenth Muse” and “The Poetess.” Scholars believe they exchanged poems and ideas – and, as both were Lesbian aristocrats, quite possibly they shared many amphorae of wine.

According to scholars, Alceus was involved in politics and frequented the fine wine-tasting events of the time: orgies.

In late October, as my husband Llewellyn King and I traveled north by bus from Athens International Airport to Eretria, a port town on the island of Evia, I tried to decode the some of the technicolored tags on the wall of the suburban railway that runs alongside the highway. There was one repeated tag in all caps that I, or anyone, could decipher: ORGY.

We were enroute to the Association of European Journalists (AEJ) annual congress, and the tag reminded me of Nora Ephron’s quip, “Working as a journalist is exactly like being a wallflower at an orgy.”

Greek Wine: It Is Drinking Better

Retsina, retsina, everywhere, but I didn’t drink a drop of it in Evia, which is one of the three major production centers of the resin-infused wine.

Isaia Tsaousidou, AEJ international president, and president of the Greek section, who organized this year’s congress, wanted to acquaint us with some of the excellent single-varietal and blended wines from Evia. She arranged a tour and lunch (an al fresco, typical Greek lunch of salad, pasta, grilled meats, French fries and very drinkable red and white wines) at the family owned Lykos Winery.

Enologist Vicky Avramidou Vassiliki told journalists that Lykos wines are made with Greek and international varietals, grown on Evia and the mainland. “Our Kratistos, a red wine made from 100 percent Agiorgitko grapes, and Malagousia, a white wine made from 100 percent Malagousia grapes, are very popular,” she said, adding that the bottling of Malagousia vintage 2022 has started.

In the Lycos Winery

The winery is decorated with wine barrels brightly painted with the wisdom of ancient and other sages.

Lykos means “wolf” in Greek, and the winery’s logo depicts the silhouette of a wolf howling at the full moon. One decorative barrel has the image of Little Red Riding Hood cuddling a wolf.

The winery, which is medium-sized, exports 50 percent of its production to the European Union, China, Japan, some U.S. states (North Carolina and New York are two) and Canada. Its wines range in price from 7 euros to “premium.”

There is a Greek saying that “Wine pleases the heart.” It also pleases the face: The winery now has a cosmetic line made from grape seed oil, which contains polyphenols. These plant compounds have been known to not just slow the aging process, but reverse signs of aging, like sun spots, fine lines, and wrinkles. Pip pip hooray!

All You Need Is Love

On the grounds of the Miramare, the seaside hotel in Eretria where the AEJ was holding its congress, I noticed an elderly man who I thought was headed to a local bocce match. He sported a white fedora trimmed with a black-and-white ribbon, a white shirt, and white pants.

Turns out, Nicos Papapostolou is a philanthropist and honorary member of the association’s Greek section.

At the opening session of the congress, he spoke about the Kaith Papapostolou Foundation, a charity which he founded in memory of his late wife. The foundation’s work is based on “charitable love” and supporting others in need, whether emotionally or materially.

The group’s latest effort is a 2022 calendar card, which asks, “Did I offer love today?” Every seventh day of a month is highlighted in red. On those days, “Double the happy, the one who offers!”

As translated, Papapostolou told the congress, “Our organization is imagining a society that feels its need for the right to be happy. … We want to remind people of the need of the government that people should be happy.”

Interestingly, the ancient Greeks didn’t believe that the purpose of life was to be happy but to achieve. Eudaimonia, a word used by Aristotle and Plato, is best translated as “fulfillment.” And Aristotle believed that citizens must actively participate in politics if they are to be happy — i.e., fulfilled — and virtuous.

At the Distomo Museum

Those attending this year’s AEJ congress in Central Greece had the chance to visit both the glorious museum at Delphi, the site of The Oracle, and the grim one at nearby Distomo, where the whole village was slaughtered by the Nazis in a few hours on a June.

The Distomo Museum of the Nazi Victims of June 10, 1944, contains a photos of the victims and paintings of the massacre — a large, Guernica-like one hangs in one of the rooms.

At the museum entrance, there is a blown-up photo of Maria Padiska, who has come to be known as the "Woman of Distomo,” and who died in March 2009 at the age of 84.

Her image became a world symbol of grief since the publication of an article in LIFE magazine, “What the Germans did to Greece,” on Nov. 27, 1944. The photo caption reads, "Maria Padiska still weeps, four months after the Germans killed her mother in a massacre at the Greek town of Distomo.”

Our visit to this museum was as gut-wrenching, as the documentary on Ukraine, filmed by Greek journalist Lena Kyropoulos, that we were to watch later at the congress.

The visit to the Distomo museum and the viewing of the documentary proved Winston Churchill’s point movingly, “The farther backward you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.”

Linda Gasparello is co-host and producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. She’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Jennifer Lacker: In virtual reality on a bike-and-pedestrian friendly Newport Bridge

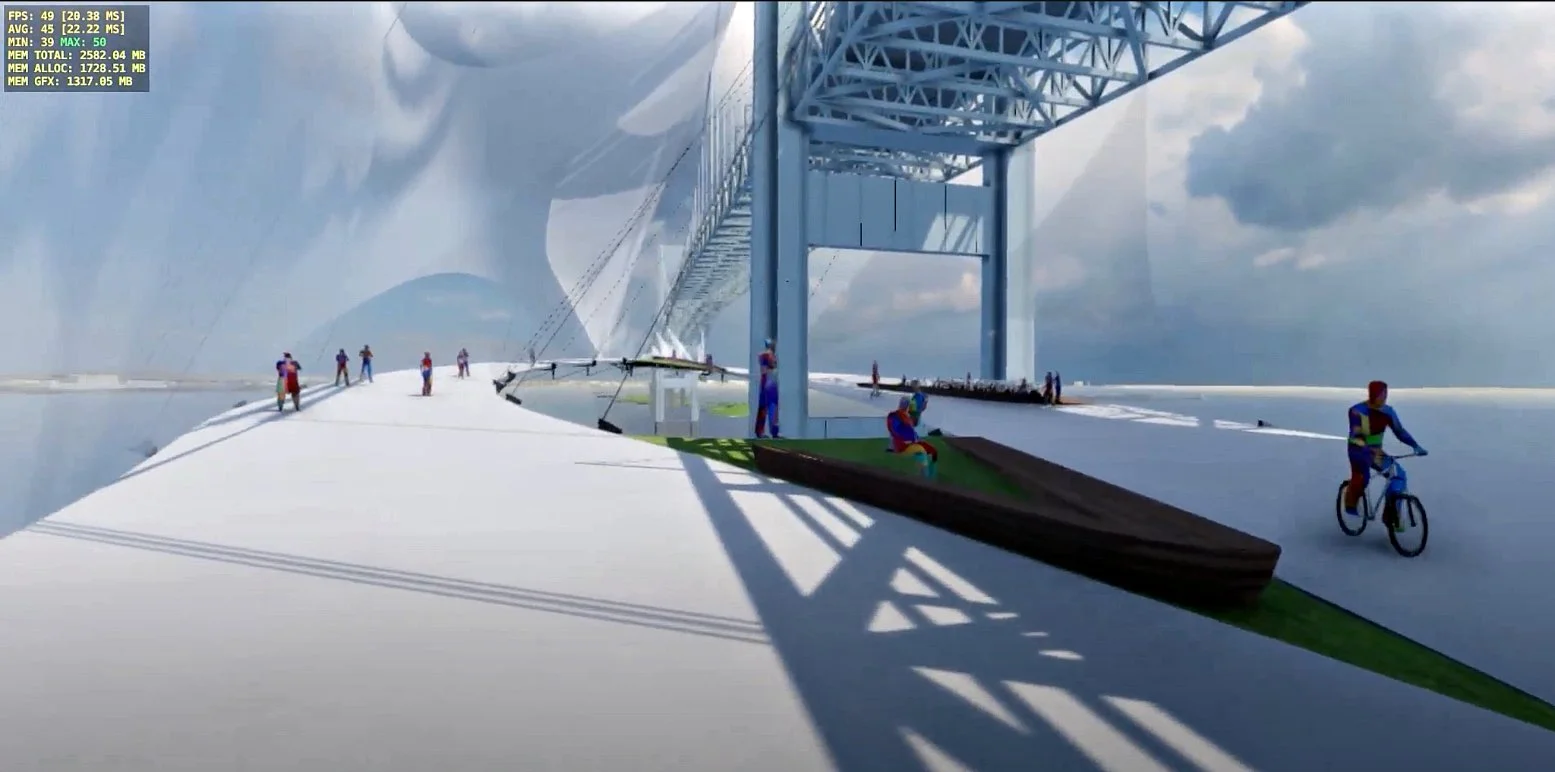

In the virtual reality of a reimagined Pell/Newport Bridge.

At the Colony House.

The brilliance of Sheldon Whitehouse, Rhode Island’s junior U.S. senator, in asking the architecture department at the Rhode Island School of Design to help envision possible scenarios of how the Pell/Newport Bridge, which connects Jamestown and Newport, could be made good for pedestrians and cyclists was on display recently at the Colony House, in Newport, presented by Bike Newport.

The event was groundbreaking, or to me mind-blowing, because it presented the possible infrastructure changes through virtual reality. I and other visitors were fitted with VR headsets and, either sitting on stationary bikes or standing on a small pad, they (including me) experienced travel through the four scenarios presented with astonishing detail.

To an older non-gamer like myself, it was an unnerving to virtually cycle around other cyclists as well as pedestrians, often feeling as if I were headed over the edge and into the water. level. The options displayed were all stunning, with corridors and public spaces connecting Newport to Jamestown within the bridge’s infrastructure.

This is a ray of hope for bike/pedestrian advocates who spend countless hours banging their head against the walls of state departments of transportation as we beg for the sort of basic safe spaces for people and their transportation that’s a given in many European countries.

While U.S. Transportation Secretary Commissioner Pete Buttigieg is doing all he can to promote changes, our plus-100-year car-centric culture is a stubborn foe, and there’s a chorus of naysayers. In Anand Giridharadas’s new book, The Persuaders, he gives a catalog of pointers from the front lines of change makers. “Sell the brownie, not recipe” is my favorite. The best persuaders, he claims, paint a picture of the future. With the tool of virtual reality that was demonstrated at the Colony House that picture can be more effectively shown and felt on a cellular level.

Jennifer Lacker is president of Bike Stonington (Conn.)

Rachana Pradhan: And now private equity is getting into the clinical-trial business

Gaston Melingue’s painting shows physician and scientist Edward Jenner vaccinating James Phipps, a boy of eight, against smallpox on May 14 1796. Jenner failed to use a control group in this early clinical trial. The vaccination apparently prevented the boy from getting the dread disease.

“We need to make sure that patients” know enough to provide “adequate, informed consent and ensure “protections about the privacy of the data.”

“We don’t want those kinds of things to be lost in the shuffle in the goals of making money.

— Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School

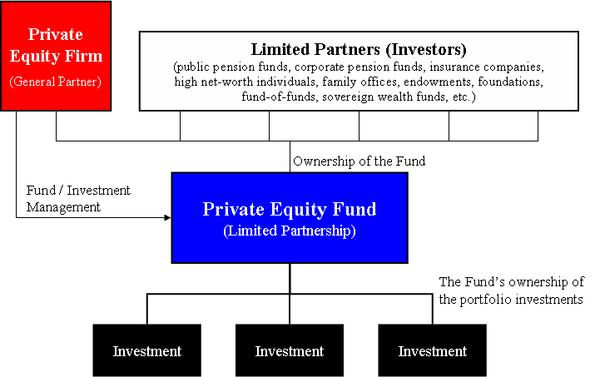

After finding success investing in the more obviously lucrative corners of American medicine — like surgery centers and dermatology practices — private-equity firms have moved aggressively into the industry’s more hidden niches: They are pouring billions into the business of clinical drug trials.

To bring a new drug to market, the FDA requires pharmaceutical firms to perform extensive studies to demonstrate safety and efficacy, which are often expensive and time-consuming to conduct to the agency’s specifications. Getting a drug to market a few months sooner and for less expense than usual can translate into millions in profit for the manufacturer.

That is why a private-equity-backed startup like Headlands Research saw an opportunity in creating a network of clinical sites and wringing greater efficiency out of businesses, to perform this critical scientific work faster. And why Moderna, Pfizer, Biogen and other drug industry bigwigs have been willing to hire it — even though it’s a relatively new player in the field, formed in 2018 by investment giant KKR.

In July 2020, Headlands announced it won coveted contracts to run clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines, which would include shots for AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, and Pfizer.

In marketing its services, Headlands described its mission to “profoundly impact” clinical trials — including boosting participation among racial and ethnic minorities who have long been underrepresented in such research.

“We are excited,” CEO Mark Blumling to bring “COVID-19 studies to the ethnically diverse populations represented at our sites.” Blumling, a drug- industry veteran with venture capital and private equity experience, told KHN that KKR backed him to start the company, which has grown by buying established trial sites and opening new ones.

Finding and enrolling patients is often the limiting and most costly part of trials, said Dr. Marcella Alsan, a public-policy professor at Harvard Kennedy School and an expert on diverse representation in clinical trials, which have a median cost of $19 million for new drugs, according to Johns Hopkins University researchers.

Before COVID hit, Headlands acquired research centers in McAllen, Texas; Houston; metro Atlanta; and Lake Charles, La., saying those locations would help it boost recruitment of diverse patients — an urgent priority during the pandemic in studying vaccines to ward off a disease disproportionately killing Black, Hispanic and Native Americans.

Headlands’s sites also ran, among other things, clinical studies on treatments to combat Type 2 diabetes, postpartum depression, asthma, liver disease, migraines, and endometriosis, according to a review of website archives and the federal Web site ClinicalTrials.gov. But within two years, some of Headlands’ alluring promises would fall flat.

In September, Headlands shuttered locations in Houston — one of the nation’s largest metro areas and home to major medical centers and research universities — and Lake Charles, a move Blumling attributed to problems finding “experienced, highly qualified staff” to carry out the complex and highly specialized work of clinical research. The McAllen site is not taking on new research as Headlands shifts operations to another South Texas location it launched with Pfizer.

What impact did those sites have? Blumling declined to provide specifics on whether enrollment targets for covid vaccine trials, including by race and ethnicity, were met for those locations, citing confidentiality. He noted that for any given trial, data is aggregated across all sites and the drug company sponsoring it is the only entity that has seen the data for each site once the trial is completed.

A fragmented clinical-trials industry has made it a prime target for private equity, which often consolidates markets by merging companies. But Headlands’ trajectory shows the potential risks of trying to combine independent sites and squeeze efficiency out of studies that will affect the health of millions.

Yashaswini Singh, a health economist at Johns Hopkins who has studied private equity acquisitions of physician practices, said consolidation has potential downsides. Singh and her colleagues published research in September analyzing acquisitions in dermatology, gastroenterology, and ophthalmology that found physician practices — a business with parallels to clinical trial companies — charged higher prices after acquisition.

“We’ve seen reduced market competition in a variety of settings to be associated with increases in prices, reduction in access and choice for patients, and so on,” Singh said. “So it’s a delicate balance.”

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, called private equity involvement in trials “concerning.”

“We need to make sure that patients” know enough to provide “adequate, informed consent,” he said, and ensure “protections about the privacy of the data.”

“We don’t want those kinds of things to be lost in the shuffle in the goals of making money,” he said.

Blumling said trial sites Headlands acquired are not charging higher prices than before. He said privacy “is one of our highest concerns. Headlands holds itself to the highest standard.”

Good or bad, clinical trials have become a big, profitable business in the private equity sphere, data shows.

Sohier said “there are few” companies in its long COVID program. That hasn’t stopped Parexel from pitching itself as the ideal partner to shepherd new products, including by doing regulatory work and using remote technology to retain patients in trials. Parexel has worked on nearly 300 covid-related studies in more than 50 countries, spokesperson Danaka Williams said.

Michael Fenne, research and campaign coordinator with the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, which studies private equity investments, said Parexel and other contract research organizations are beefing up their data capacity. The aim? To have better information on patients.

“It kind of ties into access and control of patients,” Fenne said. “Technology makes accessing patients, and then also having more reliable information on them, easier.”

Rachana Pradhan is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

KHN senior correspondent Fred Schulte and Megan Kalata contributed to this report.

But how to get there?

“Healing Pond” (mixed media and pastel on paper), by Ponnapa Prakkamakul, at Kingston Gallery, Boston

Be creative

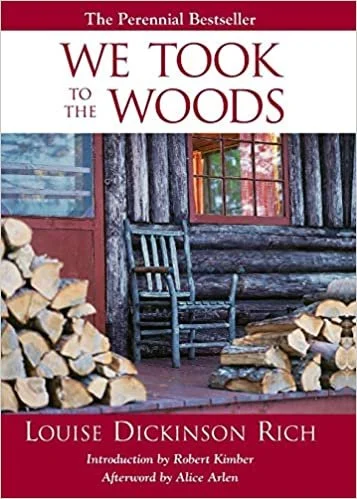

Forest Lodge, one of Louise Dickinson Rich’s houses in the Maine area she wrote about. She wasn’t exactly roughing it.

— Photo by Beverkd

"You can think of a lot of things to make out of nothing if you have to.’’

— Louise Dickinson Rich (1903-1991) in her book We Took to the Woods (1942), This, the writer’s most famous book, was autobiographical and set in the 1930s when she and husband Ralph lived near Umbagog Lake, in Maine

Royal visit from the King of Out West

Movie and early-television character Hopalog Cassidy (played by William Boyd) visits Boston in 1952.

David Warsh: Those missed Nobel Prizes

Front side of a Nobel Prize.

Photo by Jonathunder

SOMERVILLE, Mass.,

When Dale Jorgenson died last summer, of long Covid, at 89, sighs were heard throughout the worldwide community of measurement economists. Had the Swedish authorities at long last been preparing to recognize the founder of modern growth accounting? Did the Reaper rob the Harvard University econometrician of his Nobel Prize?

Probably not. It seemed that, barring exigency, the Nobel panel had decided long ago to pass him by. It was left to Martin Baily, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, to tell The Wall Street Journal’s James Hagerty that Jorgenson “should have been awarded a Nobel Prize….” The same has been said of many other often-nominated candidates, including, for example, American novelists Philip Roth, of Connecticut, and John Updike, of Massachusetts.

On a memorial service yesterday, in Harvard’s Memorial Church, it almost didn’t matter. The talk was of families, friendships, skits (including one in which Jorgenson was portrayed as Star Trek’s Mr. Spock): the old days, when the Harvard Economics Department’s youngers members and their students were housed in a converted hotel across the street from IBM’s mainframe computers. Colleagues Barbara Fraumeni, Mun Sing Ho and Benjamin Friedman spoke; so did Jorgenson’s former student Lawrence Summers. Another former student, Ben Bernanke, whose undergraduate thesis Jorgenson supervised, missed the service, on his way to Stockholm to share a Nobel Prize; the two had remained in life-long touch.

Still, the question remained, why not Jorgenson?

Certainly it was not for lack of dominating achievements in his chosen field, of growth and productivity measurement. Born in 1933, Jorgenson grew up in Montana, attended Reed College, in Portland, Ore., and, in 1959, received his PhD from Harvard, where future Nobel laureate Wassily Leontief had supervised his thesis. He took a job at the University of California at Berkeley, where he taught the graduate theory course.

In 1963 Jorgenson published “Capital Theory and Investment Behavior.” When a committee selected the 20 most important papers that the American Economic Review had published in its centenary celebration, Jorgenson’s article was among them – the only contribution to have appeared in print immediately, without the customary wait for referee reports. The 13-page paper was revolutionary in two ways, according to Robert Hall, of Stanford University:

It combined finance with the theory of the firm to generate a coherent theory of the firm’s purchase of capital inputs, an area of considerable confusion prior to Jorgenson’s work. And it also laid out a paradigm for empirical research that called for serious economic theory to provide the backbone of the measurement approach. Jorgenson showed how to integrate data and theory.

As Berkeley boiled over with student protests in the 1960s, its best economists began to leave for Harvard: first Richard Caves and Henry Rosovsky, then David Landes, and, in 1969, Jorgenson. They were part of Harvard’s response to having been eclipsed in economics beginning 25 years earlier, by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Kenneth Arrow, Zvi Griliches, Martin Feldstein, and John Meyer were recruited as well, from Stanford, Chicago, Oxford and Yale respectively.

In 1971, Jorgenson won the bi-annual John Bates Clark Medal, awarded for contributions to economics before the recipients turned 40, as had Griliches, in 1965, and Arrow, in 1957. Feldstein would be similarly recognized in 1977.

Jorgenson’s contributions continued at a steady pace for more than 50 years at Harvard. The most significant of these was a successful campaign to produce industry-by-industry input-output tables with which to elucidate national income accounts prepared in the 1930s. Aggregate growth accounting depended fundamentally on the concept of value-added, according to John Fernald, author of a comprehensive account of Jorgenson’s career.

But Evsey Domar had written as early as 1961 that value-added accounting was only “shoes lacking leather and made without power.” To identify the changes occurring in productivity a complete set of input-output tables would be required, disaggregated by industry, linking Leonief/Jorgenson accounting with the old national income accounts designed by Nobel laureate Simon Kuznets. .

Working with Ernst Berndt, Frank Gollop and Barbara Fraumeni, among others, Jorgenson gradually created a granular new account of the sources of growth, differentiating between inputs of capital (K), labor (L), energy (E), and materials (M). The purchase of services (S) were subsequently broken-out. Hence the KLEMS system of productivity and growth accounting, now used by governments around the world. Jorgenson served as president of the American Economic Association in 2000.

I knew Jorgenson as news people know their subjects, and I have known many of his students, too. I never followed growth accounting closely, though I read Diane Coyle’s beguiling little book GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History (Princeton, 2014), and I was sufficiently absorbed by Fernald’s Intellectual Biography of Jorgenson to suspect that a second golden age of nation income and productivity accounting, or perhaps one of platinum, already has begun. (For an especially artful introduction to the KLEMS system, see Emma Rothschild’s essay, “Where is Capital?” in Capitalism: A Journal of History and Economics).

Nor do I know much about early 19th Century naval history. There was, however, something in Jorgenson’s leadership style (and a leader he unmistakably was) that reminded me of the lore surrounding Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson – his precise and formal manner, clipped speech, wry humor, zest in explaining to friends the innovations he prepared, and the admiration and loyalty he elicited from his students and colleagues.

Hearing their stories over the years, I was reminded one day of the signal that Nelson sent his squadrons as the battle of Trafalgar was about to begin – “England expects that every man will so his duty.” Never mind that “the little touch of Dale in the night” sometimes meant wakefulness on nights before examinations. More often his most successful students spoke of encouragement and surprising warmth. Further evidence of the inner man: a 50-year marriage to a professionally successful wife, two children (he worked at home three days a week) and three grandchildren.

If Jorgenson’s sense was that the Swedes, too, would do their duty, apparently they did not conceive their duty quite the same way. Perhaps the pride he took in his work was too obvious to them. He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1989, sometimes seen as a consolation prize. Perhaps too much umbrage had been given MIT; there were those 13 volumes of Jorgenson’s collected papers, published with the author’s subvention, five more than those of Paul Samuelson; Griliches had been embarrassed to publish one. (The one-time collaborators (“The Explanation of Productivity Change,” in 1967) were often nominated together for their complementary work.)

Griliches died in 1999; Jorgenson soldiered on, adding to his portfolio the economics of energy, the environment, emerging nations’ development, and even pandemics, via the KLEMS system. He became embedded in the major tax debates of the day. But the attention that theoretical economists paid to increasing returns to scale beginning in the ‘80’s was of little interest to an apostle of neo-classically based empirical analysis.

Jorgenson was sometimes called a “Reedie,” after the selective college he attended, celebrated for a distinctive sort of intellectuality, rivaled by Cal Tech, Swarthmore College and St. Johns College. Some 1,500 undergraduates today, 175 faculty members, providing constant feedback but no grades in real time, a measure thought to encourage hard work and long horizons. Only after they had graduated and applied to graduate schools were their transcripts revealed. Legend had it that Jorgenson was among the handful who over the years had received straight A grades in all his courses, and perhaps a few beyond. Certainly he received encouragement from Carl M. Stevens, a 1951 Harvard PhD in economics then teaching at Reed.

Touring a plaza of his hometown library that had been named for him, the author Phillip Roth was asked if the cold-shoulder from the Swedish Academy bothered him. “Newark is my Stockholm,” Roth replied. Reed College was Jorgenson’s Newark; bi-annual KLEMS project meetings are his Stockholm.

David Warsh, veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

‘Dripping jawful’

North Haven and the Fox Islands Thoroughfare viewed from Rockland, Maine.

“The bight is littered with old correspondences.

Click. Click. Goes the dredge,

and brings up a dripping jawful of marl.

All the untidy activity continues,

awful but cheerful.’’

—From “The Bight,’’ by Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, who was born in Worcester and died in Boston but lived in many places in between, including North Haven, Maine, where she had a summer place.

Preserving a luminous beauty

“Stillness” (oil on canvas), by Massachusetts artist Penny Billings, at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

Copyright 2022 / Penny Billings Fine Art

She says:

“My work is influenced by the incredibly diverse landscape of the Northeast, with its changing seasons and the striking intersection of light and shadow at certain times of day. I strive to capture and preserve that same luminous beauty in my oil paintings.’’

Building our competition

“Shipyard #11, Qili Port, Zhejiang Province, China” (chromogenic color print), by Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, in his show “Earth Observed,’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, through April 16.

The museum says:

“Burtynsky’s largest retrospective in the Northeast examines the artist’s career-long documentation of human impact on nature—an endeavor that has led him across North America and around the world, and that has resulted in some of the most iconic, beautiful, and unsettling images of our times.

A public path to the shore

Looking at Weekapaug, showing the breachway, jetty, channel, Fenway Beach and oceanfront homes.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

This will drive some affluent summer people bonkers but Rhode Island Atty. Gen. Peter Neronha rightfully expressed his “strong support” for making the “Spring Avenue Extension” and a sand path in Westerly’s exclusive Weekapaug section a state-recognized public right-of-way to the beach.

Well-heeled locals understandably have tried to block the public from this passage but there’s plenty of historical evidence that supports the public’s right to use this route. Legal decisions and disputes involving access to the ocean in New England go back to colonial days.

“It is time to ensure Spring Avenue is permanently and forever public and free of the private encroachments that have unlawfully hindered access to the shore in recent decades,” Mr. Neronha told the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council.

Will this be a precedent for ending other Rhode Island shoreline-access disputes?

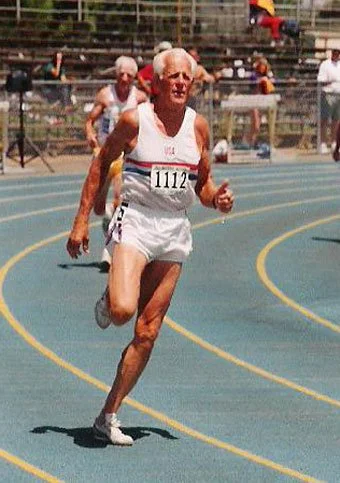

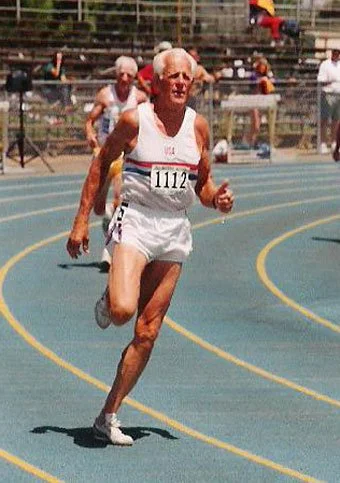

Chris Powell: If gender means nothing maybe age doesn’t either

— Photo by TrackCE

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Now that loony ideology is trumping biology and the country is entering an age where merely wishing or thinking is supposed to make it so, why stop with transgenderism? If boys and men can be girls and women, and vice versa, even for competitive sports and bathroom use, thereby nullifying Title IX and sexual privacy, how can age restrictions be fair anymore?

If you're really only as old as you feel, mandatory retirement ages must go. So must age group rules in sports.

If wishing or thinking makes it so, who has the right to tell any 40-year-old that he can't play on a Little League team and enjoy hitting a 12-year-old's pitches out of the park or knocking over the 13-year-old trying to tag him as he slides into third base?

For a few years Connecticut has been nervously humoring this nonsense with the rationale offered by Gov. Ned Lamont -- that it hasn't happened much, just famously in high school girls cross-country meets. This is only to say that it doesn't matter because it has happened to someone else's daughters. To object risks being called a "transphobe" or worse, though no one is denying the right of people to impersonate the other sex outside of competitive sports and bathrooms.

Similarly, people in Connecticut are being mocked or worse just for arguing that schools should not press topics like transgenderism on the youngest children.

Lacking good argument, the transgender cultists rely heavily on intimidation, because it works better. So the nonsense may not end in Connecticut until the women's basketball teams at Stanford or Tennessee recruit some 6-foot-9, 275-pound transgender forwards who leave UConn players writhing on the court with ACL tears or worse.

xxx

MORE UNPUBLIC EDUCATION: New London High School's football coach says he has been forced to resign because of an insignificant incident during a game with Ledyard High School. According to The Day of New London, the school's athletic director refuses to explain because, he says, it's a personnel matter.

That's public education in Connecticut, again resorting to the oldest non-sequitur of government -- that there never can be any accountability with personnel, so go away. Unfortunately most people do go away.

But the law does not say that personnel matters in government cannot be reviewed and discussed in public. To the contrary, while teachers enjoy a special-interest exemption for their annual performance evaluations, the law makes public other records of school employment and particularly records involving misconduct.

A request to New London's school superintendent for access to all records involving the coach might show the public what happened with him and let the public make an informed judgment about it. If the superintendent refused that much accountability, the city's Board of Education could be appealed to, and then the state Freedom of Information Commission.

School administrators might be able to delay accountability for a year or two -- probably not forever. But stalling accountability for a year or two is usually enough for public education to avoid being public.

Public education won't really be public at all until the "personnel matter" non-sequitur is challenged whenever it is cynically trotted out.

xxx

LET WINE JOIN BEER: Supermarkets in Connecticut have renewed their campaign to persuade the General Assembly and governor to change state law to let them to sell wine. That certainly would be a convenience. While supermarkets already are allowed to sell beer, anyone who would buy wine or liquor has to make a separate trip to a liquor store.

There is no good reason for this trouble, only a bad reason -- Connecticut's long subservience to the retailers and distributors of alcoholic beverages, accomplished through laws sharply limiting alcoholic-beverage retailing permits and prohibiting price competition, essentially turning the alcoholic beverage business into political patronage and what is called rent seeking. As a result Connecticut has unnecessarily high alcoholic-beverage prices.

Supermarkets should be allowed to sell beer, wine, and liquor just as liquor stores should be allowed to sell groceries -- that is, if government ever means to serve the public interest rather than the special interest

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com).

Take a left for scandal

In New Hampshire’s Lakes Region: G.I.W. refers to the village of Gilmanton Iron Works, in Gilmanton, the model for Peyton Place, the town in the once scandalous 1956 novel of the same name by Grace Metalious. Gilmanton Irons Works is named for a long-gone unprofitable mining operation.

— Photo by William Morgan

In Gilmanton: Iron Works Bridge in 1910.

Art, not anguish

“Teardrop (After Robert Irwin)” (polished stainless steel with mirror finished, halogen lighting), by Pakistani-American artist Anila Quayyum Agha, in the group show “Tradition Interrupted,” at the Lamont Gallery, at Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, N.H., through Dec. 10.

— Courtesy of Talley Dunn Gallery, in Dallas

The gallery says that each artist in this exhibition was tasked to "weave contemporary ideas with traditional art and craft," with the aim of bringing experiences of their cultures and marrying them to different mediums that complement each other.

And beware factoids

ESPN headquarters, in Bristol, Conn.

— Photo by Jkinsocal

“Part-time information and full-time opinions can be very dangerous.’’

— Chris Berman (born 1955), long-time ESPN anchor

Hit this link on why ESPN is based in Bristol.