This last season

Covered bridge in Henniker, N.H.

— Photo by Jokermage

”This change of light and how it wakes you with uneasiness

and the shift of wind from the north that rains down ice

might keep you covered for months. You swear this will

be your last season in a place you believe is disappearing.’’

— From “This Last Place,’’ by Maura MacNeil, a Deering, N.H., poet and writing teacher at New England College, in Henniker.

America's culture of cocophany

Paint on a piece of film wrap over a bass speaker playing very loud music.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

America is a noisy place, often painfully so. But many people seem to like that.

The other night, six of us went to a Mexican restaurant in Providence called Dolores. The food was pretty good, though the service was a bit slow because of what appeared to be the staffing shortage that bedevils many restaurants. Always a tough business, but much more so in the Age of COVID.

It was a painful meal for us. The bass-heavy background music made it very arduous to try to hear what people across the table were saying. The next day, our ears still hurt from two hours in the racket.

And yet the place was packed on that Monday evening. You could see customers shouting to each other, but most were smiling. My hunch is that for many people in our culture of cacophony, a noisy place signifies excitement and somehow evokes the happy idea that they’re where the action is – that they’re not missing out.

Since the last two generations have grown up amidst increasing noise – rock music, etc. – that’s more and more difficult to escape – perhaps quiet makes them nervous.

Meanwhile, the gasoline-powered leaf blowers shriek from dawn to dusk, polluting the air and driving away the birds and indeed many walkers who try to avoid the racket, the fumes and the grit by finding other routes. And drugstores have automated bad music.

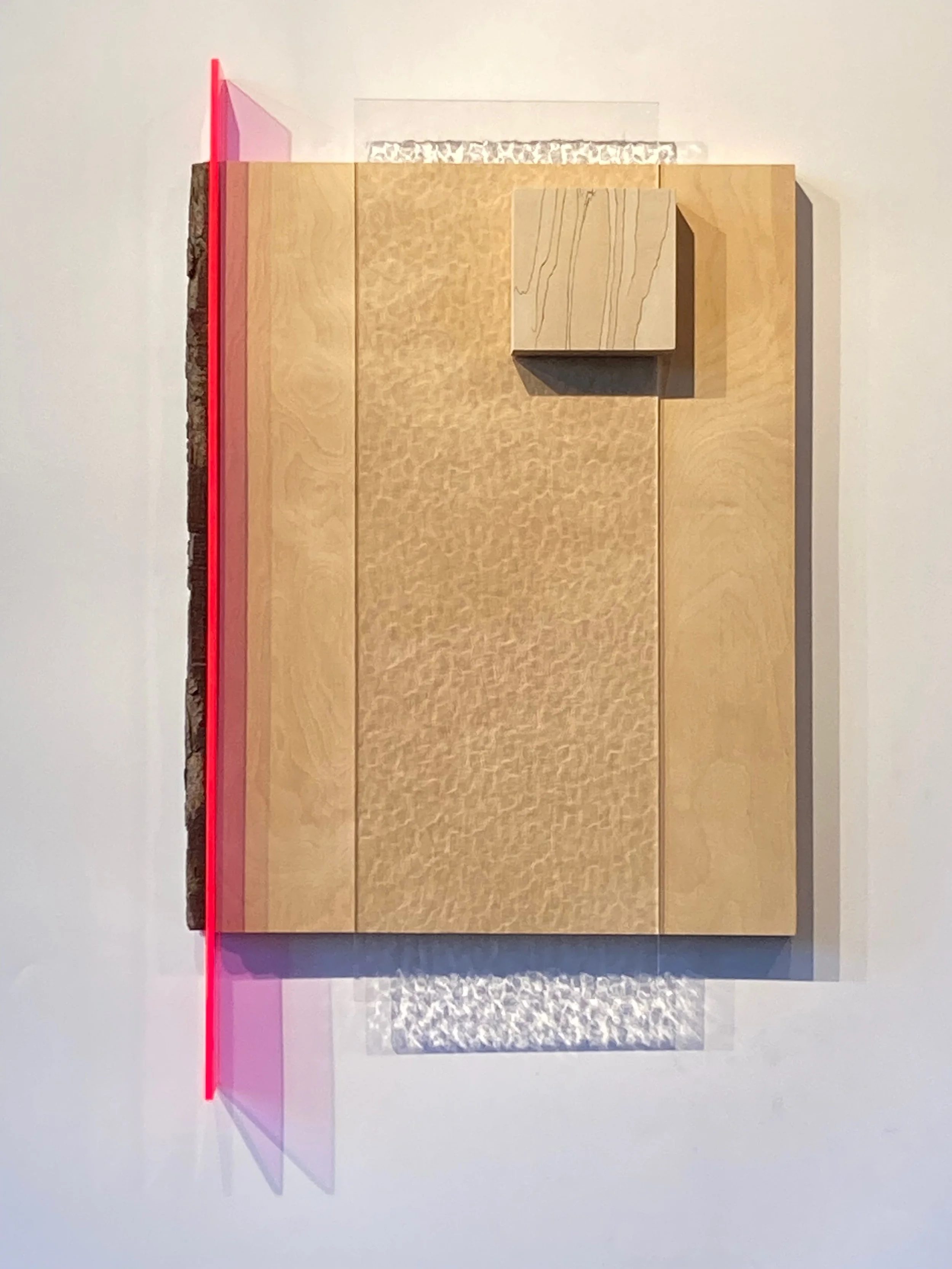

‘Fragile systems of beauty’

“Breakthrough” (sculptural collage, mixed media including wood panels, tree bark, acryli and plexiglass), by Boston area artist Luanne Witkowski, in her show “Clarity,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, March 1-April 2.

The gallery says:

Ms. Witkowski “uses both found natural materials and fabricated cast-offs and scraps, focusing on composition, recurrent pattern, minimalist form, and color to create an artistic response to the fragile systems of beauty and the raw power that exist in both the natural world and urban landscapes. For the artist, this response is accessible through the contemplative creative process of perception, when we allow ourselves to relax into our senses. Witkowski’s daily routines - walking through forests, parks and countryside of wildlife, flora and fauna followed by engagement with city streets, glass and artificial light - interweave the interaction and juxtaposition of her various materials. In doing so, she recalls the shared experiences grounded in each of us: creating a perceptual and spiritual relationship for recognition of and solace for the self. This approach to the identification of the individual with landscape and environment is enlarged by a desire to discover and connect with the particular indwelling essence or energy of clarity.’’

Llewellyn King: New hope arises for fusion energy after years of broken hearts, but….

The target chamber of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s National Ignition Facility in California where 192 laser beams delivered more than 2 million joules of ultraviolet energy to a tiny fuel pellet to create fusion ignition on Dec. 5, 2022.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

While the rafters are ringing with praise for the nuclear-fusion breakthrough at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), let me inject a sour note: This isn’t the beginning of cheap, safe, non-polluting electricity.

It is a scientific milestone, not an electricity one. Science tantalizes but it also deceives. Often the mission turns out not to be the one for which years of scientific research was aiming.

I would remind the world that science stirred great hope futilely with the idea of superconductivity at ambient temperatures, after some laboratory success.

The history of fusion itself is a clear illustration of expectations dashed, revived, resurrected, and dashed again. Now there is some hope with a stunning lab success: the first future experiment with “gain,” meaning more energy came out of the experiment than went into it.

Fusion has been the goal, the light at the end of the tunnel for nuclear researchers for over 60 years. In that time there have been false prophets, failed attempts, elaborate claims, and just hard slog.

That hard slog has shown what is possible: More power has been achieved in a fusion experiment for a fraction of a second. That is a huge success but it isn’t limitless electricity, as some have heralded.

Fission — which makes possible our power reactors and warships — is the splitting of the atom to release heat that is converted, via steam, into electricity.

Fusion, beguiling fusion, seeks to do what happens in stars and the sun — the fusing of two atoms together to produce heat, which, in a reactor, would be used to create steam and turn turbines, making electricity.

Governments and researchers have salivated over the possibility of fusion for decades and it has been well-funded worldwide, compared with other energy sources.

Getting fusion temperatures at or above those on the sun must be achieved to fuse two deuterium atoms together. Deuterium, also called “heavy hydrogen,” is an isotope of hydrogen. If you can do that and sustain the reaction for months and years, you can then design a reactor that would create steam, or use some other fluid, to turn a turbine.

There are two approaches scientists have used to get fusion. One is inertial fusion, used in the breakthrough at the National Ignition Facility at LLNL, near San Francisco, which involves hitting a pellet with a concentrated beam of energy: The lab used 192 super-powerful lasers to get fusion.

In the early 1980s, I spent time at LLNL and watched an experiment to hit the target with big accelerators. There were, as I recall, eight of them the size of cars. The research scientist showing me the facility said that accelerators the size of locomotives were needed to continue the experiments.

The other approach to get fusion is the tokamak, a Russian word, which describes a doughnut-shaped machine where a plasma is superheated with electricity, and the whole thing is held together in powerful magnetic fields. This is the technology being pursued internationally by a 35-nation consortium at the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), in Cadarache, southern France.

This tokamak, or toroidal approach, is the one most favored in the community to succeed eventually as a source of heat to make electricity.

Also, a lot of solid work on fusion has been done at the General Atomics facility in La Jolla, Calif., and at research facilities across the United States and around the world. I visited the General Atomics site many times, crawled inside the machine, and wondered at the math and science that have gone into the pursuit of fusion.

Back in the 197os, physicist Keeve “Kip” Siegel believed that he could achieve fusion with simple, off-the-shelf optical lasers. He died of a stroke in March 1975, while testifying before the Joint Congressional Committee on Atomic Energy in defense of his laser fusion research.

Bob Guccione, founder and publisher of Penthouse, hooked up with a former member of Congress from Washington State, Mike McCormack, and together they sought to promote fusion.

Two eminent scientists, Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann, thought they had a breakthrough with so-called cold fusion. But this chemical process hasn’t panned out.

When I was looking at that fusion experiment at LLNL in the early 1980s, the researcher showed me on his computer a wonderful new way of communicating with other scientists around the world. I thought it was just a Telex on steroids and went back to questions about fusion, despite my guide's enthusiasm for the new communications system.

It was the Internet, and I missed the big story — as big as a story can get — to keep reporting on fusion. You can see why I may be soured.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C. He’s a long-time journalist, speaker and consultant in the energy sector.

Web site: whchronicle.com

‘I’m spoiled’

— Photo by Niranjan Arminius

Start of a game of water polo on Main Street, Saxtons River, after the July 4th parade in 2013. The game is played by volunteer firefighters with fire hoses, trying to spray the ball down the street to a goal. Looking west at the Saxtons River Historical Society (a former Congregational church).

“I’m spoiled by the lack of traffic, the beauty all around me, the night sky, the wildlife, and having more space and time to think and be creative.’’

— Julie Moir Messervy, Saxtons River, Vt.-based landscape architect, in Vermont Life magazine. Saxtons River is a village in the town of Rockingham.

Movements in lives

“Dance of the Titled Mothers” (acrylic and natural dyes and pigments on burlap and handwoven cotton cloth) by Boston-based artist Stephen Hamilton, in his show “Passages: Stephen Hamilton,’’ at LaiSun Keane Gallery, Boston, through Dec. 31.

— Photo courtesy of LaiSun Keane Gallery

Mr. Hamilton incorporates both Western and African techniques in his work. He says this show "examines the movement between adolescence and adulthood, adulthood and elderhood, as well as life, death, and rebirth in African and African-American folklore and philosophy." For more information, please visit here.

George McCully: We need to battle AI robotization

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Every reader of this journal is being affected by the highly exceptional historical phenomenon we are all experiencing: an age of total transformation, of paradigm-shifts in virtually every field of human endeavor. Our own field—postsecondary education and training—is just one among all the others. Younger colleagues, though they may not like it, are experiencing this as a given and generally constructive condition, building their future theaters of operations. Senior colleagues raised and entering the profession in the 20th Century paradigm of “higher education,” experience current transformations as disruptive—disintegrative and destructive of their originally sought-for and later accustomed professional world. Students seeking credentials for future jobs are confused and problematically challenged.

It helps to understand all this turmoil as an inexorable historical process. This article will describe that process, and then address how we individually, and organizations like NEBHE, might best deal with it.

We happen to be living in a very rare kind of period in Western history, in which everything is being radically transformed at once. Paradigm-shifts in particular fields happen frequently, but when all fields are in paradigm-shifts simultaneously, it is an Age of Paradigm Shifts. This has happened only three times in Western history, about a thousand years apart—first with the rise of Classical Civilization in ancient Greece; second with the fall of Rome and the rise of medieval Christianity; and third in the “early modern” period—when the Renaissance of Classicism, the Reformation of Christianity, the Scientific Revolution, the Age of Discovery, the rise of nation states, secularization and the Enlightenment, cumulatively replaced medieval civilization and gave birth to “modern” history in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Modernity, however, is now unraveling, in a transformation with significant unique features.

First and most noticeable is its speed, occurring in a matter of decades (since circa 1990) rather than centuries. The acceleration of change in history, driven by technology’s increasing pace and power, has been going on for centuries—perhaps first noticed by Machiavelli in the Renaissance. Today, the driving transformational force is the rapidly accelerating innovations in digital and internet technology, in particular, increasingly autonomous Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Second, for the first time our technology is increasingly acknowledged to be running ahead of human control; it is becoming autonomous and self-propelled, and we are already struggling to catch up with it.

Third, whereas the first three transformations were intended by human agents, for the first time now, driven by technological advances, we have no clue as to where the technology is headed—what will be the dénouement or if that is even possible.

And fourth, under these conditions of constant change both internally and all around us, strategic planning in any traditional sense is impossible because there are no solid handles we can grasp and hold onto as collaborators or guides into the future. We are adrift in an unprecedently tumultuous sea of change.

For people in post-secondary education and training, this critical situation is especially agonizing because we are in society at various thresholds of adulthood, where personal and professional futures are crucially chosen and determined. We have extraordinarily heavy responsibility for the futures of individuals, of society, of humanity and of our planet—precisely when we have inadequate competence, coordination and self-confidence. We are where humans will address the innovations and disruptions critical to the future, where strategic knowledge and intelligence will be most needed, and where historical understanding will therefore be crucial.

Let us first acknowledge that each, and all, of our jobs sooner or later, can and probably will be robotized by AI. Its technical capacity already exists, noted by many journalists and scholars, for thinking and writing (publicly available GPT-3, and next year GPT-4), visual and musical arts, interactive conversations, cerebral games (chess, Go, et al.) and other problem-solving activities, at quality levels equal to and frequently excelling human-generated work. Significant technological advances are happening almost weekly, and AI nowadays develops these autonomously, written in code it developed for its own machine-learning use. Its aims are not excellence, truth or other value-intensive products, but common-denominator performances adequate to compete commercially with works created by humans and indistinguishable (by humans—though software is being developed intended do this) from them, produced at blinding speed. Suddenly there could appear countless new “Bach” fugues, novels in Hemingway’s style, etchings by Rembrandt, news articles and editorials or academic work—all mass-produced by machines.

Administrative functions—numerary, literary, interactive, decision-making, etc.—will be widely available to ordinary individuals and institutions. What will remain for which humans are needed to do, at prices that yield living wages, is a real question already being considered hypothetically.

Speed bumps helping to shield us from faster robotization are (temporarily at least) the availability of sufficient capitalization, and the time required for dissemination. Here, the fact that we work much more slowly than AI is a temporary but ultimately self-defeating blessing. The driving incentive for takeover is the robots’ greater cost-effectiveness. In the long run, robots work more cheaply and much faster than humans, outweighing losses of quality in performance.

For individuals, our best defense against robotic takeover is for each of us to identify and enhance whatever aspects of our jobs that humans can still do best, which means that we should all start redefining our work in humanistic and value-intensive directions, so that when robotization comes knocking, decision-makers will go for the low-hanging fruit, allowing the easiest transitions first, leaving some margins of continued freedom for humans to continue doing their jobs.

A clear possibility, and I believe necessity, for postsecondary education and training lies in that distinction, extending from individuals’ lives and work to institutions and organizations like NEBHE and their instruments such as this journal. The rise of machine learning (AI) is a wedge, compelling us to cease referring to all post-secondary teaching and learning as “higher education.” There is nothing “higher” about robotic training and commercial credentialing for short-term “gig economy” job markets. Let us therefore first define our terms more carefully and precisely.

“Education,” as in “liberal education,” traditionally means “self-development”; “training” customarily means “knowledge and skills development.” The two are clearly distinct, but not separate except in extreme cases; when mixed, the covering designation depends on which is primary and intentional in each particular case.

In other words, our education helps define who we are; our training helps define what we are—doctor, lawyer, software engineer, farmer, truckdriver, manufacturer, etc. Who we are is an essential and inescapable part of all of our lives that’s always with us; what we are is optional—what we chose to do and be at given times of our lives.

Education is intrinsically humanistic and value-intensive, therefore most appropriately (but not necessarily) taught and learned between humans; training can be well-taught by AI, imparting knowledge and skills from robots to humans. Ideally, to repeat for emphasis, both education and training usually involve each other in varying proportions—when education includes knowledge and skills development, and training is accompanied by values. But these days especially, we should be careful not to confuse them.

For individuals, certainly education and possibly training are continuing lifelong pursuits. AI will take over training most easily and first, especially as rapid changes and transformations overtake every field, already producing a so-called “gig” economy in which work in any given capacity increasingly becomes temporary, more specialized and variegated, affecting the lives and plans of young employees today. Rapid turnover requires rapid increases in training, certifying, credentialing programs and institutions. Increasing demand for it has evoked many new forms of institutionalization—e.g., online and for-profit in addition to traditional postsecondary colleges and universities—as well as an online smorgasbord of credentials for personal subscriptions. For all of these, AI offers optimal procedures and curricula, increasingly the only way to keep up with exploding demand; thus, the proliferation of kinds of institutions, programs, curricula, courses and credentials is sure to continue.

The need for education will also increase, so the means of delivery and content in such a disturbed environment will require extraordinarily innovative creativity, resilience and agile adaptability among educators. The highest priority will have to be keeping up with the transformations—figuring out how best to insert the cultivation of humane values, best accomplished between human teachers (scholars, professors, practitioners) and learners, and provided by educational institutions and individuals, into the many new forms of training. Ensuring that this happens will be a major responsibility of today’s educational infrastructure and personnel, because AI does not, and does not have to, care about values. Will individual learners care? Not necessarily—for consumers of credentials, personal and even professional values apart from their commercial value are not a top priority. Whether employers will care about them is a major issue for concern by educators.

Here, the paradigm-shift in post-secondary education and training arises for attention by umbrella organizations like, for example, NEBHE and this journal. When NEBHE was founded, in 1955, the dominant paradigm in post-secondary education was referred to simply as “higher” education” (the “HE” in those acronyms)—residing in liberal arts colleges (including community colleges) and universities. The New England governors, realizing that the future prosperity of our region would be heavily dependent on “higher” education, committed their states to the shared pursuit of academic excellence in which New England was arguably the national leader.

That simple paradigm, however, has been superseded in practice. Today, the much greater variety of institutional forms and procedures, much more heavily reliant on rapidly developing technology, and the recognized need for broader inclusion of previously neglected and disadvantaged populations, calls for reconceptualization and rewording, reflecting the broader new reality of post-secondary, lifelong, continuing education and training.

New England is no longer the generally acknowledged national leader in this proliferation; the paradigm-shifting is a nationwide phenomenon. Nonetheless, though the rationale for a New England regional umbrella organization for both educational and training infrastructure has been transformed, it persists. Now it is needed to help the two branches of post-secondary human and skills development work in mutually reinforcing ways, despite the challenges—which are accelerating and growing—for both branches. Lifelong continuing education and training will be enriched, strengthened and refined by their complementary collaboration for all demographic constituencies.

How this might happen among an increasing variety of institutions still needs to be worked out in this highly fluid and dynamic environment. That is the urgent challenging mission and responsibility of the umbrella organizations. At the ground-level, individual professionals need to be reassessing their jobs defensively in humanistic directions, for which they will be fortified with a strategic sense of mission as a crucial element in the comprehensive infrastructure. Beyond that, coordinated organization will help form multiple alliances among institutions in a united front against encroaching AI robotization. This may be the only pathway for retaining roles and responsibilities by humans into the future.

George McCully is a historian, former professor and faculty dean at higher education institutions in the Northeast, professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy.

Liz Szabo: Why the lack of pediatric beds? They don’t pay well

— Photo by Robert Lawton

Hasbro Children’s Hospital, in Providence

“We have doctors who are cleaning beds so we can get children into them faster.’’

—Megan Ranney, M.D,. deputy dean at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

The dire shortage of pediatric hospital beds plaguing the nation this fall is a byproduct of financial decisions made by hospitals over the past decade, as they shuttered children’s wards, which often operate in the red, and expanded the number of beds available for more profitable endeavors like joint replacements and cancer care.

To cope with the flood of young patients sickened by a sweeping convergence of nasty bugs — especially respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, and coronavirus — medical centers nationwide have deployed triage tents, delayed elective surgeries, and transferred critically ill children out of state.

A major factor in the bed shortage is a years-long trend among hospitals of eliminating pediatric units, which tend to be less profitable than adult units, said Mark Wietecha, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. Hospitals optimize revenue by striving to keep their beds 100 percent full — and filled with patients whose conditions command generous insurance reimbursements.

“It really has to do with dollars,” said Dr. Scott Krugman, vice chairman of pediatrics at the Herman and Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore. “Hospitals rely on high-volume, high-reimbursement procedures from good payers to make money. There’s no incentive for hospitals to provide money-losing services.”

The number of pediatric inpatient units in hospitals fell 19% from 2008 to 2018, according to a study published in 2021 in the journal Pediatrics. Just this year, hospitals have closed pediatric units in Boston and Springfield, Mass.; Richmond, Va., and Tulsa, Okla.

The current surge in dangerous respiratory illnesses among children is yet another example of how COVID-19 has upended the health-care system. The lockdowns and isolation that marked the first years of the pandemic left kids largely unexposed — and still vulnerable — to viruses other than covid for two winters, and doctors are now essentially treating multiple years’ worth of respiratory ailments.

The pandemic also accelerated changes in the health-care industry that have left many communities with fewer hospital beds available for children who are acutely ill, along with fewer doctors and nurses to care for them.

When intensive-care units were flooded with older COVID patients in 2020, some hospitals began using children’s beds to treat adults. Many of those pediatric beds haven’t been restored, said Dr. Daniel Rauch, chairman of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on hospital care.

In addition, the relentless pace of the pandemic has spurred more than 230,000 health-care providers — including doctors, nurses, and physician assistants — to quit. Before the pandemic, about 10% of nurses left their jobs every year; the rate has risen to about 20%, Wietecha said. He estimates that pediatric hospitals are unable to maintain as many as 10% of their beds because of staffing shortages.

“There is just not enough space for all the kids who need beds,” said Dr. Megan Ranney, who works in several emergency departments in Providence, including Hasbro Children’s Hospital. The number of children seeking emergency care in recent weeks was 25% higher than the hospital’s previous record.

“We have doctors who are cleaning beds so we can get children into them faster,” said Ranney, a deputy dean at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

There’s not great money in treating kids. About 40% of U.S. children are covered by Medicaid, a joint federal-state program for low-income patients and people with disabilities. Base Medicaid rates are typically more than 20% below those paid by Medicare, the government insurance program for older adults, and are even lower when compared with private insurance. While specialty care for a range of common adult procedures, from knee and hip replacements to heart surgeries and cancer treatments, generates major profits for medical centers, hospitals complain they typically lose money on inpatient pediatric care.

When Tufts Children’s Hospital closed 41 pediatric beds this summer, hospital officials assured residents that young patients could receive care at nearby Boston Children’s Hospital. Now, Boston Children’s is delaying some elective surgeries to make room for kids who are acutely ill.

Rauch noted that children’s hospitals, which specialize in treating rare and serious conditions such as pediatric cancer, cystic fibrosis, and heart defects, simply aren’t designed to handle this season’s crush of kids acutely ill with respiratory bugs.

Even before the autumn’s viral trifecta, pediatric units were straining to absorb rising numbers of young people in acute mental distress. Stories abound of children in mental crises being marooned for weeks in emergency departments while awaiting transfer to a pediatric psychiatric unit. On a good day, Ranney said, 20% of pediatric emergency room beds at Hasbro Children’s Hospital are occupied by children experiencing mental health issues.

In hopes of adding pediatric capacity, the American Academy of Pediatrics joined the Children’s Hospital Association last month in calling on the White House to declare a national emergency due to child respiratory infections and provide additional resources to help cover the costs of care. The Biden administration has said that the flexibility hospital systems and providers have been given during the pandemic to sidestep certain staffing requirements also applies to RSV and flu.

Doernbecher Children’s Hospital at Oregon Health & Science University has shifted to “crisis standards of care,” enabling intensive care nurses to treat more patients than they’re usually assigned. Hospitals in Atlanta, Pittsburgh, and Aurora, Colorado, meanwhile, have resorted to treating young patients in overflow tents in parking lots.

Dr. Alex Kon, a pediatric critical-care physician at Community Medical Center in Missoula, Montana, said providers there have made plans to care for older kids in the adult intensive care unit, and to divert ambulances to other facilities when necessary. With only three pediatric ICUs in the state, that means young patients may be flown as far as Seattle or Spokane, Washington, or Idaho.

Hollis Lillard took her 1-year-old son, Calder, to an Army hospital in Northern Virginia last month after he experienced several days of fever, coughing, and labored breathing. They spent seven anguished hours in the emergency room before the hospital found an open bed and transferred them by ambulance to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Maryland.

With proper therapy and instructions for home care, Calder’s virus was readily treatable: He recovered after he was given oxygen and treated with steroids, which fight inflammation, and albuterol, which counteracts bronchospasms. He was discharged the next day.

Although hospitalizations for RSV are falling, rates remain well above the norm for this time of year. And hospitals may not get much relief.

People can be infected with RSV more than once a year, and Krugman worries about a resurgence in the months to come. Because of the coronavirus, which competes with other viruses, “the usual seasonal pattern of viruses has gone out the window,” he said.

Like RSV, influenza arrived early this season. Both viruses usually peak around January. Three strains of flu are circulating and have caused an estimated 8.7 million illnesses, 78,000 hospitalizations, and 4,500 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Krugman doubts the health-care industry will learn any quick lessons from the current crisis. “Unless there is a radical change in how we pay for pediatric hospital care,” Krugman said, “the bed shortage is only going to get worse.”

Liz Szabo is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

The power lines around us

“Rugged Road and Power Lines” (welded steel, rugs, installations together), by Boston-based Andy Zimmermann, in his show “Rugged Road,’’ at Boston Sculptors Gallery, Dec. 14-Jan. 290.

The gallery says:

“Two ambitious installations, ‘Rugged Road’ and ‘Power Lines,’ combined to suggest a landscape, anchor the show, which also includes smaller-scale welded steel sculptures and digital collages.

The titular installation, ‘Rugged Road,’ features a collection of rugs suspended in a steel scaffolding constructed to form a composition evocative of a flower or an explosion. Collected from a range of sources, including yard sales, flea markets, thrift stores and ebay, some are new and made to look used while others are truly worn, and come from as far afield as Morocco, Turkey, and Afghanistan. The rugs suggest a wide range of human conditions, from a symbol of great opulence, to a wrapper carried by a refugee family, from a piece of trash, to a magic flying carpet.

“The ‘Rugged Road’ construction is situated within the surrounding installation entitled ‘Power Lines.’ These welded steel structures clearly refer to high-tension electric lines and their support towers. Placement and forced perspective describe a rugged landscape, with symbolic and political overtones.

“The re-purposing of materials is an underlying theme for Zimmermann. Most of the rugs are used, providing archeological evidence of decades of life in a household. Much of the steel scaffolding has been used by the artist in previous installations. The signs of use and wear evident in these materials become part of the content in their present iteration. This concept is further explored in the digital collages on display. They include images of some Zimmermann’s earlier artworks, elements of autobiography to be unearthed.’’

Another triumph for New England biotech?

The Philip A. Sharp Building, in Cambridge, which houses the headquarters of Biogen

— Photo by Astrophobe

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’ in GoLocal24.com

This is another “we’ll see’’ situation that gives hope.

Japan’s Eisai Co. and Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen Inc. have developed a drug, called lecanemab, that destroys the amyloid protein plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Patients in the drug trial have had a slowing of symptoms. Researchers have much to learn about the drug’s benefits, side-effects and cost, but the apparent breakthrough may the most hopeful sign yet that a highly effective treatment of this terrible dementia might be in the offing.

Hit this link for The New England Journal of Medicine article on this.

Further, since the buildup of abnormal proteins in the brain is also seen in such (usually) old-age-related ailments as Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease, lecanemab may have wider applications than just for Alzheimer’s as the population continues to age.

This could be another triumph for New England’s bio-tech industry, but it may take many months to find out for sure.

‘Like profanation’

— Photo by Christoph Geisler

I had for my winter evening walk—

No one at all with whom to talk,

But I had the cottages in a row

Up to their shining eyes in snow.

And I thought I had the folk within:

I had the sound of a violin;

I had a glimpse through curtain laces

Of youthful forms and youthful faces.

I had such company outward bound.

I went till there were no cottages found.

I turned and repented, but coming back

I saw no window but that was black.

Over the snow my creaking feet

Disturbed the slumbering village street

Like profanation, by your leave,

At ten o’clock of a winter eve.

— “Good Hours,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Chris Powell: The Pequots’ casino privilege and a history lesson

The gigantic Foxwoods casino and resort complex, in the hills of eastern Connecticut. It’s owned by people at least partly descended from members of the Pequot tribe living in the area when the English move into it in the 17th Century.

— Photo by Elfenbeinturm

Engraving depicting the attack on the Pequot fort at Mystic on May 26, 1637, from John Underhill’s Newes from America, London, 1638

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Student performance, and even attendance, in Connecticut's public schools are crashing, but not to worry. With Gov. Ned Lamont presiding, the state Education Department and the state's five officially recognized Indian tribes announced the other day that they will create a model curriculum in Native American studies. The curriculum will be offered to the schools, where, if it is used, may crowd out basic academic teaching, as "social-emotional learning" already is doing.

Indeed, the Native American studies curriculum may be especially useful for distracting from the crash of public education. Everyone in authority can keep looking busy while carefully avoiding relevance to the disaster.

Of course if students ever managed to read at grade level, it would be great to have a more accurate and comprehensive account of the country's history, overcoming what kids pick up from cowboys-and-Indians theater. But such an account is not likely to emerge from anything assembled by the Education Department and the Indian tribes. The curriculum probably will be constructed to rationalize perpetual grievance, victimhood and privilege. After all, legislation to create the curriculum was proposed by state Sen. Cathy Osten (D-Sprague, or maybe more accurately, D-Foxwoods).

A news report about the curriculum suggested that the history of the Indian tribes and the European settlers who founded Connecticut is such a sensitive subject that it will be uncomfortable to relate, apparently because some think that assigning guilt will be necessary.

Nonsense. For the Connecticut history to be taught here is only the history of mankind -- tribalism and the struggle to overcome it, with the peculiarly American denouement whereby, as society began to overcome it, tribalism was seen as an excellent mechanism for delivering political patronage and so was restored and embedded in law for perpetuity.

In early Connecticut there were more than two tribes, the Europeans and Indians. There were multiple Indian tribes with shifting alliances, and the peace was broken as much as by the Indians as the Europeans. The Pequots, whose remote descendants today claim entitlement to perpetual victimhood because of the tribe's near-extermination by English colonists in a battle in Mystic in 1637, oppressed other Indian tribes and so were hated by them. The name "Pequot" meant "destroyer."

So the Mohegans, Narragansetts and Niantics joined the Europeans to destroy the Pequots themselves -- men, women and children alike, an atrocity far greater than the atrocities that had been inflicted by the Pequots on their enemies, atrocities that had prompted the war.

The Pequot chief Sassacus, who was away with a raiding party at the time of the Mystic massacre, fled to the west and was killed not by the English but by the Mohawks, who sent his severed head and hands to the colonists in Hartford as an offering of friendship.

Of course, the extermination of most of the Pequots was not quickly followed by an age of equality, light and happy assimilation. Indian lands were bought or expropriated, more easily because the Indians did not share the Europeans' concept of private property. Hewing to its old ways, Indian culture faded under the burden of discrimination.

But over the decades intermarriage and vast new immigration to what became the United States hastened assimilation of Connecticut's ethnicities, and eventually, though only a half century ago, full equality under the law, if not quite in actual living conditions, was established. Now the descendants of the old tribes and the various ethnicities were trying to make a living more or less in the same culture.

Whereupon government, in its endless thirst for revenue, contrived to dress up casino gambling as a form of ethnic reparations for ancient wrongs that lacked surviving victims. In southeastern Connecticut certain people who lived in raised ranches and worked at Electric Boat like everybody else suddenly could claim to be oppressed on behalf of their distant ancestors. In the name of this ancestry state government gave them a casino duopoly and thus perpetual wealth to be inherited by their descendants at the expense of the rest of society.

Almost as quickly as it had arrived in Connecticut, equality under the law was undone. As a political matter this new ethnic privilege will require perpetuating the false impression of victimhood. Hence the Education Department's new curriculum.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

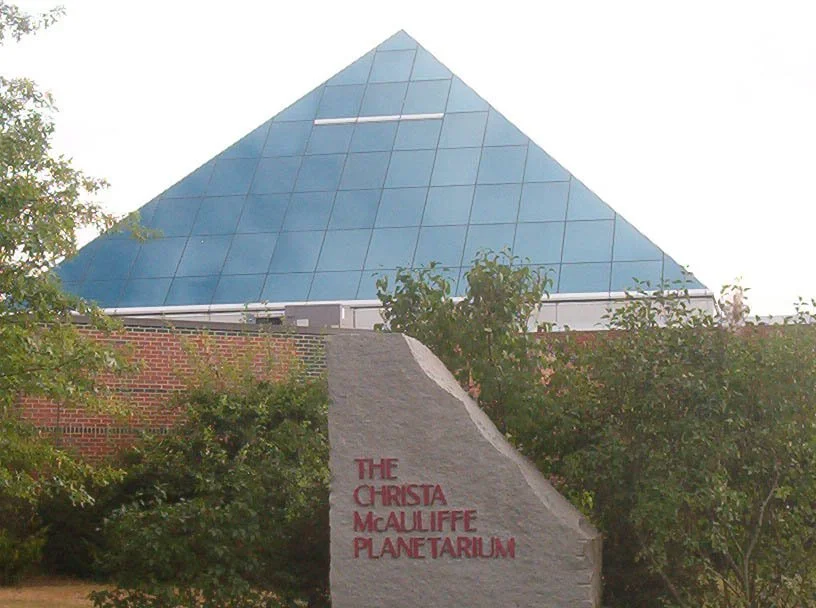

‘A world without boundaries’

Christa McAuliffe

The McAuliffe-Shepard Discovery Center, in Concord, N.H. The Shepard refers to Alan Shepard (1923-1998), a Derry, N.H., native and early astronaut.

— Photo by Karmafist

"You have to dream. We all have to dream. Dreaming is okay. Imagine me teaching from space, all over the world, touching so many people's lives. That's a teacher's dream! I have a vision of the world as a global village, a world without boundaries. Imagine a history teacher making history!"

— Christa Auliffe (born 1948), the Concord (N.H.) High School history teacher who was one of the seven astronauts killed in the breakup of the Challenger space shuttle on Jan. 28, 1986.

Ginette Saimprevil: The long road to education equality in Boston

At 46 Joy St., Boston, the Abiel Smith School, was founded in 1835 and is the oldest public school in the U.S. built for the sole purpose of educating African-American children. It houses the Museum of African American History.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Boston has had an extraordinarily long and tumultuous history as a fulcrum of the fight for the equal education of Black people.

Black Bostonians began petitioning the Massachusetts legislature for greater access to the public school system in 1787. In 1835, the Abiel Smith School opened—the first building erected for the sole purpose of housing a Black public school. However, conditions in this underfunded, segregated school were below standard, and the Black community continued to campaign for equal-education opportunities. While public school segregation was officially outlawed in 1855, de facto segregation continued to be the reality in Boston.

In 1965, the legislature passed the Racial Imbalance Act, which outlawed segregation in public schools and, most significantly, defined segregated schools as those with a student body comprised of more than 50 percent of a particular racial group. Yet despite this ruling, Boston School Committee members refused to implement plans to integrate the city’s schools, and the relentless struggle for equal education continued.

In 1974, a federal court-ordered busing plan to end school segregation in Boston resulted in an eruption of protests and violence in the streets, as well as death threats against the judge in the case. Even innocent children being bussed were attacked. Despite the continuation of busing for more than a decade, white flight and a later decision to allow children in residentially segregated areas to attend neighborhood schools resulted in resegregation of many of Boston’s schools. By the 2017-18 school year, more than half of Boston Public Schools were profoundly segregated—even more than in 1965, according to a 2018 report by The Boston Globe. This situation persists to this day.

Boston’s segregated schools, with largely Black and Latinx students, tend to have a higher student-to-teacher ratio as well as older textbooks, lower quality facilities, fewer school counselors per student and other inequalities. This inevitably means that these students will face greater difficulties when it comes to gaining admission to college, completing their degrees and embarking on careers.

Secret sauce

At Bottom Line (BL), we seek to level the playing field by providing students with ongoing in-person advising from their senior year in high school through college graduation. Our trained, professional advisers deliver intensive, relationship-based, one-on-one advising, and they partner with students to select and gain admission to a college that is the best possible fit—academically, financially and culturally.

Our access advisers support high school seniors, based on their individual needs, in navigating the college application process using our LEAAD curriculum:

List: generating a list of colleges suited to students’ academic and financial situations.

Essay: brainstorm, writing and editing essays.

Applications: completing college applications.

Affordability: securing financial aid.

Decision: making a college choice.

Advisers and students review students’ options to select a college that best meets academic, financial and personal needs, with students receiving transition-to-college programming over the summer before their first college year.

The “secret sauce” in the Bottom Line approach is the holistic support—considering the whole student and building authentic relationships through our hybrid model. Our advisers conduct some in person meetings and provide remote support via video, phone and text communication.

In the college-access program, students meet with their advisers about 10 times a year. In the success program in college, students are paired with a success adviser who works with them one on one. Advisers offer regular support in the four areas most likely to cause a student to drop out of college: Degree, Employability, Affordability and Life, or DEAL.

This comprehensive support is provided for up to six years or until a student graduates. Our career-connections team and advisors provide coaching and support to help students/recent graduates build their social and career capital to launch mobilizing careers. Support includes mock interviewing, resume-writing workshops, help securing job shadows and internships, and networking events to prepare students for the workforce.

This work has a significant impact on our students and communities we serve. On average, our students earn nearly double their family income in their first job out of college. Our individualized college access, success and career connections support to students also results in a historic six-year graduation rate of 76 percent (more than double the national average).

Bottom Line’s model is recognized for its rigorous, externally validated proof-of-impact on college enrollment, persistence and graduation. An independent research report on “The Bottom Line on College Advising: Large Increases in Degree Attainment” confirms the impact of current BL programs and the notable potential for expansion. Researchers found that compared to the controlled group, Bottom Line students are 23 percent more likely to graduate from college. The researchers also added, “While the observed degree effects are quite consistent across different types of students, the fact that BL primarily serves students of color furthermore suggests that substantial expansion of the BL model could contribute to increased racial equity and mobility in the U.S.”

The estimated impact of advising on bachelor’s degree attainment is roughly as large as the (conditional on aptitude) gap in degree attainment between children from families in the first and fourth quartile of the income distribution.

I know from my personal as well as professional experience that the Bottom Line model works. My family emigrated from Haiti when I was 10. While my parents instilled in me a tradition of diligence and perseverance, they had no experience with higher education and were unable to help me navigate college-admissions and financial-aid processes. Fortunately, I was introduced to the BL program when I was a high school junior, and my adviser helped me find my way to a full tuition scholarship at Bowdoin College and a fulfilling career helping other students succeed.

Recently, our organization received a $15 million grant from philanthropist MacKenzie Scott. This grant will let us accelerate implementation of our strategic plan. This plan partly includes strategies to increase the number of students in Boston, New York City and Chicago, because we know there is a need for educational equity across the nation. The goal is to directly serve 20,000 students as well as reach 400,000 indirectly.

The Abiel Smith School, the oldest public school in the U.S. built for the sole purpose of educating African American children, now houses the exhibition galleries of the Museum of African American History. The very walls of this historic building are dedicated to telling the story of the Boston abolitionist movement and equal education. It is an inspiring place to reflect on the role of education at the core of equality and the continuum of persistence and progress in Boston’s Black community. It is a centuries old story that we hope to play a role in by ensuring that more students of color attain their college degrees.

Ginette Saimprevil is executive director of Bottom Line Massachusetts.

Cold-weather creatures

“Snow Crows” ( monoprint), by Susan Amons, in the group show with Lisa Houck and Richard Remsen entitled “Managerie a Trois,’’ at Cove Street Arts, Portland, Maine, through Jan. 21.

— Photo courtesy Cove Street Arts.

The gallery says the show presents animal-themed artwork focusing on creatures often associated with winter. For more information, please visit here.

Main Street in downtown Biddeford

— Photo by Lookinforahome

Europeans first settled in what became Biddeford, which had been well-populated by Native Americans, in 1616. In the 19th Century, Biddeford became a prosperous industrial center, with granite quarries and brickyards and lumber, grain and textile mills. In recent years, some of the old mills have been converted into retail stores, art studios, cultural-event spaces and upscale housing.

Biddeford hosts the University of New England.

Some comforting yarns

“Stock,’’ (oil on linen), by Cindy Rizza, in her show “Cindy Rizza: Habitats,” at the Rochester (N.H.) Museum of Fine Arts through Jan. 6.

— Photo courtesy Rochester Museum of Fine Arts.

The museum says:

The museum says the show features comforting oil paintings of familiar domestic items. Her paintings "delicately [render] everyday domestic objects we use to create a sense of security; their utilitarian and decorative functions act to create a sanctuary. Her work simultaneously brings a sense of warm nostalgia and chilling loss.’’

The museum is open Monday to Friday, 8:30 a.m. — 6 p.m. The Rochester Museum of Fine Arts is located at 150 Wakefield Street, Rochester, NH. For more information, please visit here.

The Cocheco River provided power for Rochester’s early factories.

—Photo by AlexiusHoratius

Linda Gasparello: Postcards from Greece -- joyous and tragic

Distomo, Greece — site of great beauty and great barbarity

I know -- through my education and experience -- the Latin phrase, “In vino veritas.” But until recently, I didn’t know the Latins lifted it from Alceus of Mytilene, a 6th-Century BC lyric poet from the Greek island of Lesbos, who said, “Wine, window into a man.”

Alceus was a contemporary of Sappho, known as the “Tenth Muse” and “The Poetess.” Scholars believe they exchanged poems and ideas – and, as both were Lesbian aristocrats, quite possibly they shared many amphorae of wine.

According to scholars, Alceus was involved in politics and frequented the fine wine-tasting events of the time: orgies.

In late October, as my husband Llewellyn King and I traveled north by bus from Athens International Airport to Eretria, a port town on the island of Evia, I tried to decode the some of the technicolored tags on the wall of the suburban railway that runs alongside the highway. There was one repeated tag in all caps that I, or anyone, could decipher: ORGY.

We were enroute to the Association of European Journalists (AEJ) annual congress, and the tag reminded me of Nora Ephron’s quip, “Working as a journalist is exactly like being a wallflower at an orgy.”

Greek Wine: It Is Drinking Better

Retsina, retsina, everywhere, but I didn’t drink a drop of it in Evia, which is one of the three major production centers of the resin-infused wine.

Isaia Tsaousidou, AEJ international president, and president of the Greek section, who organized this year’s congress, wanted to acquaint us with some of the excellent single-varietal and blended wines from Evia. She arranged a tour and lunch (an al fresco, typical Greek lunch of salad, pasta, grilled meats, French fries and very drinkable red and white wines) at the family owned Lykos Winery.

Enologist Vicky Avramidou Vassiliki told journalists that Lykos wines are made with Greek and international varietals, grown on Evia and the mainland. “Our Kratistos, a red wine made from 100 percent Agiorgitko grapes, and Malagousia, a white wine made from 100 percent Malagousia grapes, are very popular,” she said, adding that the bottling of Malagousia vintage 2022 has started.

In the Lycos Winery

The winery is decorated with wine barrels brightly painted with the wisdom of ancient and other sages.

Lykos means “wolf” in Greek, and the winery’s logo depicts the silhouette of a wolf howling at the full moon. One decorative barrel has the image of Little Red Riding Hood cuddling a wolf.

The winery, which is medium-sized, exports 50 percent of its production to the European Union, China, Japan, some U.S. states (North Carolina and New York are two) and Canada. Its wines range in price from 7 euros to “premium.”

There is a Greek saying that “Wine pleases the heart.” It also pleases the face: The winery now has a cosmetic line made from grape seed oil, which contains polyphenols. These plant compounds have been known to not just slow the aging process, but reverse signs of aging, like sun spots, fine lines, and wrinkles. Pip pip hooray!

All You Need Is Love

On the grounds of the Miramare, the seaside hotel in Eretria where the AEJ was holding its congress, I noticed an elderly man who I thought was headed to a local bocce match. He sported a white fedora trimmed with a black-and-white ribbon, a white shirt, and white pants.

Turns out, Nicos Papapostolou is a philanthropist and honorary member of the association’s Greek section.

At the opening session of the congress, he spoke about the Kaith Papapostolou Foundation, a charity which he founded in memory of his late wife. The foundation’s work is based on “charitable love” and supporting others in need, whether emotionally or materially.

The group’s latest effort is a 2022 calendar card, which asks, “Did I offer love today?” Every seventh day of a month is highlighted in red. On those days, “Double the happy, the one who offers!”

As translated, Papapostolou told the congress, “Our organization is imagining a society that feels its need for the right to be happy. … We want to remind people of the need of the government that people should be happy.”

Interestingly, the ancient Greeks didn’t believe that the purpose of life was to be happy but to achieve. Eudaimonia, a word used by Aristotle and Plato, is best translated as “fulfillment.” And Aristotle believed that citizens must actively participate in politics if they are to be happy — i.e., fulfilled — and virtuous.

At the Distomo Museum

Those attending this year’s AEJ congress in Central Greece had the chance to visit both the glorious museum at Delphi, the site of The Oracle, and the grim one at nearby Distomo, where the whole village was slaughtered by the Nazis in a few hours on a June.

The Distomo Museum of the Nazi Victims of June 10, 1944, contains a photos of the victims and paintings of the massacre — a large, Guernica-like one hangs in one of the rooms.

At the museum entrance, there is a blown-up photo of Maria Padiska, who has come to be known as the "Woman of Distomo,” and who died in March 2009 at the age of 84.

Her image became a world symbol of grief since the publication of an article in LIFE magazine, “What the Germans did to Greece,” on Nov. 27, 1944. The photo caption reads, "Maria Padiska still weeps, four months after the Germans killed her mother in a massacre at the Greek town of Distomo.”

Our visit to this museum was as gut-wrenching, as the documentary on Ukraine, filmed by Greek journalist Lena Kyropoulos, that we were to watch later at the congress.

The visit to the Distomo museum and the viewing of the documentary proved Winston Churchill’s point movingly, “The farther backward you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.”

Linda Gasparello is co-host and producer of White House Chronicle, on PBS. She’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

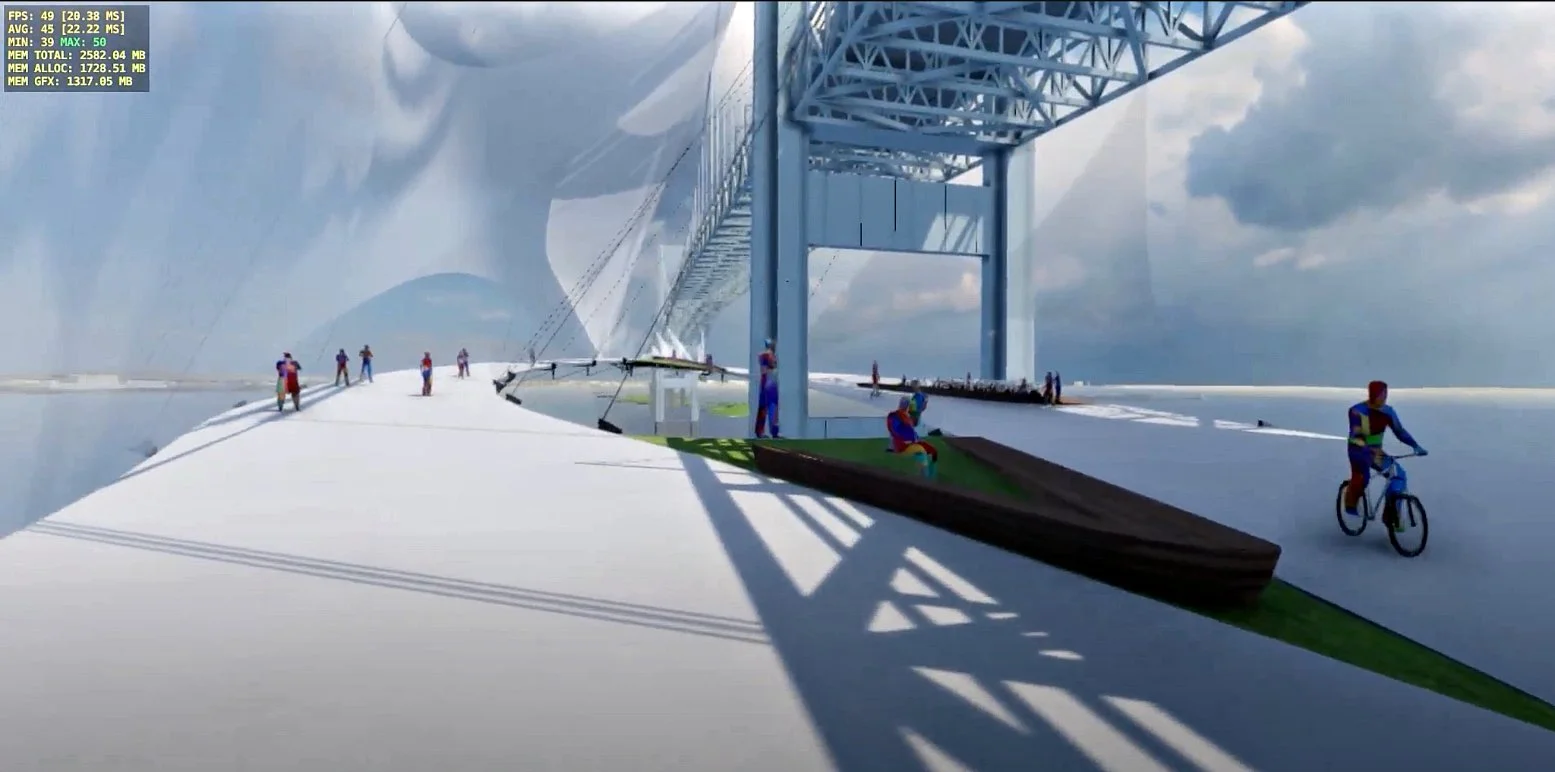

Jennifer Lacker: In virtual reality on a bike-and-pedestrian friendly Newport Bridge

In the virtual reality of a reimagined Pell/Newport Bridge.

At the Colony House.

The brilliance of Sheldon Whitehouse, Rhode Island’s junior U.S. senator, in asking the architecture department at the Rhode Island School of Design to help envision possible scenarios of how the Pell/Newport Bridge, which connects Jamestown and Newport, could be made good for pedestrians and cyclists was on display recently at the Colony House, in Newport, presented by Bike Newport.

The event was groundbreaking, or to me mind-blowing, because it presented the possible infrastructure changes through virtual reality. I and other visitors were fitted with VR headsets and, either sitting on stationary bikes or standing on a small pad, they (including me) experienced travel through the four scenarios presented with astonishing detail.

To an older non-gamer like myself, it was an unnerving to virtually cycle around other cyclists as well as pedestrians, often feeling as if I were headed over the edge and into the water. level. The options displayed were all stunning, with corridors and public spaces connecting Newport to Jamestown within the bridge’s infrastructure.

This is a ray of hope for bike/pedestrian advocates who spend countless hours banging their head against the walls of state departments of transportation as we beg for the sort of basic safe spaces for people and their transportation that’s a given in many European countries.

While U.S. Transportation Secretary Commissioner Pete Buttigieg is doing all he can to promote changes, our plus-100-year car-centric culture is a stubborn foe, and there’s a chorus of naysayers. In Anand Giridharadas’s new book, The Persuaders, he gives a catalog of pointers from the front lines of change makers. “Sell the brownie, not recipe” is my favorite. The best persuaders, he claims, paint a picture of the future. With the tool of virtual reality that was demonstrated at the Colony House that picture can be more effectively shown and felt on a cellular level.

Jennifer Lacker is president of Bike Stonington (Conn.)

Rachana Pradhan: And now private equity is getting into the clinical-trial business

Gaston Melingue’s painting shows physician and scientist Edward Jenner vaccinating James Phipps, a boy of eight, against smallpox on May 14 1796. Jenner failed to use a control group in this early clinical trial. The vaccination apparently prevented the boy from getting the dread disease.

“We need to make sure that patients” know enough to provide “adequate, informed consent and ensure “protections about the privacy of the data.”

“We don’t want those kinds of things to be lost in the shuffle in the goals of making money.

— Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School

After finding success investing in the more obviously lucrative corners of American medicine — like surgery centers and dermatology practices — private-equity firms have moved aggressively into the industry’s more hidden niches: They are pouring billions into the business of clinical drug trials.

To bring a new drug to market, the FDA requires pharmaceutical firms to perform extensive studies to demonstrate safety and efficacy, which are often expensive and time-consuming to conduct to the agency’s specifications. Getting a drug to market a few months sooner and for less expense than usual can translate into millions in profit for the manufacturer.

That is why a private-equity-backed startup like Headlands Research saw an opportunity in creating a network of clinical sites and wringing greater efficiency out of businesses, to perform this critical scientific work faster. And why Moderna, Pfizer, Biogen and other drug industry bigwigs have been willing to hire it — even though it’s a relatively new player in the field, formed in 2018 by investment giant KKR.

In July 2020, Headlands announced it won coveted contracts to run clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines, which would include shots for AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson, Moderna, and Pfizer.

In marketing its services, Headlands described its mission to “profoundly impact” clinical trials — including boosting participation among racial and ethnic minorities who have long been underrepresented in such research.

“We are excited,” CEO Mark Blumling to bring “COVID-19 studies to the ethnically diverse populations represented at our sites.” Blumling, a drug- industry veteran with venture capital and private equity experience, told KHN that KKR backed him to start the company, which has grown by buying established trial sites and opening new ones.

Finding and enrolling patients is often the limiting and most costly part of trials, said Dr. Marcella Alsan, a public-policy professor at Harvard Kennedy School and an expert on diverse representation in clinical trials, which have a median cost of $19 million for new drugs, according to Johns Hopkins University researchers.

Before COVID hit, Headlands acquired research centers in McAllen, Texas; Houston; metro Atlanta; and Lake Charles, La., saying those locations would help it boost recruitment of diverse patients — an urgent priority during the pandemic in studying vaccines to ward off a disease disproportionately killing Black, Hispanic and Native Americans.

Headlands’s sites also ran, among other things, clinical studies on treatments to combat Type 2 diabetes, postpartum depression, asthma, liver disease, migraines, and endometriosis, according to a review of website archives and the federal Web site ClinicalTrials.gov. But within two years, some of Headlands’ alluring promises would fall flat.

In September, Headlands shuttered locations in Houston — one of the nation’s largest metro areas and home to major medical centers and research universities — and Lake Charles, a move Blumling attributed to problems finding “experienced, highly qualified staff” to carry out the complex and highly specialized work of clinical research. The McAllen site is not taking on new research as Headlands shifts operations to another South Texas location it launched with Pfizer.

What impact did those sites have? Blumling declined to provide specifics on whether enrollment targets for covid vaccine trials, including by race and ethnicity, were met for those locations, citing confidentiality. He noted that for any given trial, data is aggregated across all sites and the drug company sponsoring it is the only entity that has seen the data for each site once the trial is completed.

A fragmented clinical-trials industry has made it a prime target for private equity, which often consolidates markets by merging companies. But Headlands’ trajectory shows the potential risks of trying to combine independent sites and squeeze efficiency out of studies that will affect the health of millions.

Yashaswini Singh, a health economist at Johns Hopkins who has studied private equity acquisitions of physician practices, said consolidation has potential downsides. Singh and her colleagues published research in September analyzing acquisitions in dermatology, gastroenterology, and ophthalmology that found physician practices — a business with parallels to clinical trial companies — charged higher prices after acquisition.

“We’ve seen reduced market competition in a variety of settings to be associated with increases in prices, reduction in access and choice for patients, and so on,” Singh said. “So it’s a delicate balance.”

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, called private equity involvement in trials “concerning.”

“We need to make sure that patients” know enough to provide “adequate, informed consent,” he said, and ensure “protections about the privacy of the data.”

“We don’t want those kinds of things to be lost in the shuffle in the goals of making money,” he said.

Blumling said trial sites Headlands acquired are not charging higher prices than before. He said privacy “is one of our highest concerns. Headlands holds itself to the highest standard.”

Good or bad, clinical trials have become a big, profitable business in the private equity sphere, data shows.

Sohier said “there are few” companies in its long COVID program. That hasn’t stopped Parexel from pitching itself as the ideal partner to shepherd new products, including by doing regulatory work and using remote technology to retain patients in trials. Parexel has worked on nearly 300 covid-related studies in more than 50 countries, spokesperson Danaka Williams said.

Michael Fenne, research and campaign coordinator with the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, which studies private equity investments, said Parexel and other contract research organizations are beefing up their data capacity. The aim? To have better information on patients.

“It kind of ties into access and control of patients,” Fenne said. “Technology makes accessing patients, and then also having more reliable information on them, easier.”

Rachana Pradhan is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

KHN senior correspondent Fred Schulte and Megan Kalata contributed to this report.

But how to get there?

“Healing Pond” (mixed media and pastel on paper), by Ponnapa Prakkamakul, at Kingston Gallery, Boston