Be creative

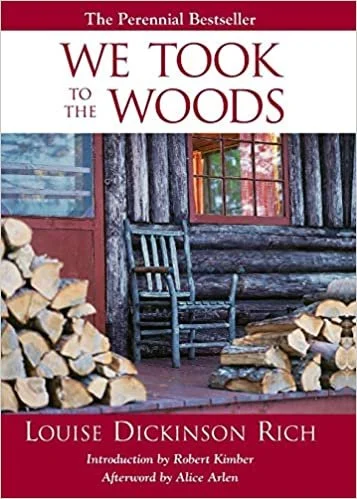

Forest Lodge, one of Louise Dickinson Rich’s houses in the Maine area she wrote about. She wasn’t exactly roughing it.

— Photo by Beverkd

"You can think of a lot of things to make out of nothing if you have to.’’

— Louise Dickinson Rich (1903-1991) in her book We Took to the Woods (1942), This, the writer’s most famous book, was autobiographical and set in the 1930s when she and husband Ralph lived near Umbagog Lake, in Maine

Royal visit from the King of Out West

Movie and early-television character Hopalog Cassidy (played by William Boyd) visits Boston in 1952.

David Warsh: Those missed Nobel Prizes

Front side of a Nobel Prize.

Photo by Jonathunder

SOMERVILLE, Mass.,

When Dale Jorgenson died last summer, of long Covid, at 89, sighs were heard throughout the worldwide community of measurement economists. Had the Swedish authorities at long last been preparing to recognize the founder of modern growth accounting? Did the Reaper rob the Harvard University econometrician of his Nobel Prize?

Probably not. It seemed that, barring exigency, the Nobel panel had decided long ago to pass him by. It was left to Martin Baily, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, to tell The Wall Street Journal’s James Hagerty that Jorgenson “should have been awarded a Nobel Prize….” The same has been said of many other often-nominated candidates, including, for example, American novelists Philip Roth, of Connecticut, and John Updike, of Massachusetts.

On a memorial service yesterday, in Harvard’s Memorial Church, it almost didn’t matter. The talk was of families, friendships, skits (including one in which Jorgenson was portrayed as Star Trek’s Mr. Spock): the old days, when the Harvard Economics Department’s youngers members and their students were housed in a converted hotel across the street from IBM’s mainframe computers. Colleagues Barbara Fraumeni, Mun Sing Ho and Benjamin Friedman spoke; so did Jorgenson’s former student Lawrence Summers. Another former student, Ben Bernanke, whose undergraduate thesis Jorgenson supervised, missed the service, on his way to Stockholm to share a Nobel Prize; the two had remained in life-long touch.

Still, the question remained, why not Jorgenson?

Certainly it was not for lack of dominating achievements in his chosen field, of growth and productivity measurement. Born in 1933, Jorgenson grew up in Montana, attended Reed College, in Portland, Ore., and, in 1959, received his PhD from Harvard, where future Nobel laureate Wassily Leontief had supervised his thesis. He took a job at the University of California at Berkeley, where he taught the graduate theory course.

In 1963 Jorgenson published “Capital Theory and Investment Behavior.” When a committee selected the 20 most important papers that the American Economic Review had published in its centenary celebration, Jorgenson’s article was among them – the only contribution to have appeared in print immediately, without the customary wait for referee reports. The 13-page paper was revolutionary in two ways, according to Robert Hall, of Stanford University:

It combined finance with the theory of the firm to generate a coherent theory of the firm’s purchase of capital inputs, an area of considerable confusion prior to Jorgenson’s work. And it also laid out a paradigm for empirical research that called for serious economic theory to provide the backbone of the measurement approach. Jorgenson showed how to integrate data and theory.

As Berkeley boiled over with student protests in the 1960s, its best economists began to leave for Harvard: first Richard Caves and Henry Rosovsky, then David Landes, and, in 1969, Jorgenson. They were part of Harvard’s response to having been eclipsed in economics beginning 25 years earlier, by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Kenneth Arrow, Zvi Griliches, Martin Feldstein, and John Meyer were recruited as well, from Stanford, Chicago, Oxford and Yale respectively.

In 1971, Jorgenson won the bi-annual John Bates Clark Medal, awarded for contributions to economics before the recipients turned 40, as had Griliches, in 1965, and Arrow, in 1957. Feldstein would be similarly recognized in 1977.

Jorgenson’s contributions continued at a steady pace for more than 50 years at Harvard. The most significant of these was a successful campaign to produce industry-by-industry input-output tables with which to elucidate national income accounts prepared in the 1930s. Aggregate growth accounting depended fundamentally on the concept of value-added, according to John Fernald, author of a comprehensive account of Jorgenson’s career.

But Evsey Domar had written as early as 1961 that value-added accounting was only “shoes lacking leather and made without power.” To identify the changes occurring in productivity a complete set of input-output tables would be required, disaggregated by industry, linking Leonief/Jorgenson accounting with the old national income accounts designed by Nobel laureate Simon Kuznets. .

Working with Ernst Berndt, Frank Gollop and Barbara Fraumeni, among others, Jorgenson gradually created a granular new account of the sources of growth, differentiating between inputs of capital (K), labor (L), energy (E), and materials (M). The purchase of services (S) were subsequently broken-out. Hence the KLEMS system of productivity and growth accounting, now used by governments around the world. Jorgenson served as president of the American Economic Association in 2000.

I knew Jorgenson as news people know their subjects, and I have known many of his students, too. I never followed growth accounting closely, though I read Diane Coyle’s beguiling little book GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History (Princeton, 2014), and I was sufficiently absorbed by Fernald’s Intellectual Biography of Jorgenson to suspect that a second golden age of nation income and productivity accounting, or perhaps one of platinum, already has begun. (For an especially artful introduction to the KLEMS system, see Emma Rothschild’s essay, “Where is Capital?” in Capitalism: A Journal of History and Economics).

Nor do I know much about early 19th Century naval history. There was, however, something in Jorgenson’s leadership style (and a leader he unmistakably was) that reminded me of the lore surrounding Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson – his precise and formal manner, clipped speech, wry humor, zest in explaining to friends the innovations he prepared, and the admiration and loyalty he elicited from his students and colleagues.

Hearing their stories over the years, I was reminded one day of the signal that Nelson sent his squadrons as the battle of Trafalgar was about to begin – “England expects that every man will so his duty.” Never mind that “the little touch of Dale in the night” sometimes meant wakefulness on nights before examinations. More often his most successful students spoke of encouragement and surprising warmth. Further evidence of the inner man: a 50-year marriage to a professionally successful wife, two children (he worked at home three days a week) and three grandchildren.

If Jorgenson’s sense was that the Swedes, too, would do their duty, apparently they did not conceive their duty quite the same way. Perhaps the pride he took in his work was too obvious to them. He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1989, sometimes seen as a consolation prize. Perhaps too much umbrage had been given MIT; there were those 13 volumes of Jorgenson’s collected papers, published with the author’s subvention, five more than those of Paul Samuelson; Griliches had been embarrassed to publish one. (The one-time collaborators (“The Explanation of Productivity Change,” in 1967) were often nominated together for their complementary work.)

Griliches died in 1999; Jorgenson soldiered on, adding to his portfolio the economics of energy, the environment, emerging nations’ development, and even pandemics, via the KLEMS system. He became embedded in the major tax debates of the day. But the attention that theoretical economists paid to increasing returns to scale beginning in the ‘80’s was of little interest to an apostle of neo-classically based empirical analysis.

Jorgenson was sometimes called a “Reedie,” after the selective college he attended, celebrated for a distinctive sort of intellectuality, rivaled by Cal Tech, Swarthmore College and St. Johns College. Some 1,500 undergraduates today, 175 faculty members, providing constant feedback but no grades in real time, a measure thought to encourage hard work and long horizons. Only after they had graduated and applied to graduate schools were their transcripts revealed. Legend had it that Jorgenson was among the handful who over the years had received straight A grades in all his courses, and perhaps a few beyond. Certainly he received encouragement from Carl M. Stevens, a 1951 Harvard PhD in economics then teaching at Reed.

Touring a plaza of his hometown library that had been named for him, the author Phillip Roth was asked if the cold-shoulder from the Swedish Academy bothered him. “Newark is my Stockholm,” Roth replied. Reed College was Jorgenson’s Newark; bi-annual KLEMS project meetings are his Stockholm.

David Warsh, veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

‘Dripping jawful’

North Haven and the Fox Islands Thoroughfare viewed from Rockland, Maine.

“The bight is littered with old correspondences.

Click. Click. Goes the dredge,

and brings up a dripping jawful of marl.

All the untidy activity continues,

awful but cheerful.’’

—From “The Bight,’’ by Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, who was born in Worcester and died in Boston but lived in many places in between, including North Haven, Maine, where she had a summer place.

Preserving a luminous beauty

“Stillness” (oil on canvas), by Massachusetts artist Penny Billings, at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

Copyright 2022 / Penny Billings Fine Art

She says:

“My work is influenced by the incredibly diverse landscape of the Northeast, with its changing seasons and the striking intersection of light and shadow at certain times of day. I strive to capture and preserve that same luminous beauty in my oil paintings.’’

Building our competition

“Shipyard #11, Qili Port, Zhejiang Province, China” (chromogenic color print), by Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, in his show “Earth Observed,’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, through April 16.

The museum says:

“Burtynsky’s largest retrospective in the Northeast examines the artist’s career-long documentation of human impact on nature—an endeavor that has led him across North America and around the world, and that has resulted in some of the most iconic, beautiful, and unsettling images of our times.

A public path to the shore

Looking at Weekapaug, showing the breachway, jetty, channel, Fenway Beach and oceanfront homes.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

This will drive some affluent summer people bonkers but Rhode Island Atty. Gen. Peter Neronha rightfully expressed his “strong support” for making the “Spring Avenue Extension” and a sand path in Westerly’s exclusive Weekapaug section a state-recognized public right-of-way to the beach.

Well-heeled locals understandably have tried to block the public from this passage but there’s plenty of historical evidence that supports the public’s right to use this route. Legal decisions and disputes involving access to the ocean in New England go back to colonial days.

“It is time to ensure Spring Avenue is permanently and forever public and free of the private encroachments that have unlawfully hindered access to the shore in recent decades,” Mr. Neronha told the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council.

Will this be a precedent for ending other Rhode Island shoreline-access disputes?

Chris Powell: If gender means nothing maybe age doesn’t either

— Photo by TrackCE

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Now that loony ideology is trumping biology and the country is entering an age where merely wishing or thinking is supposed to make it so, why stop with transgenderism? If boys and men can be girls and women, and vice versa, even for competitive sports and bathroom use, thereby nullifying Title IX and sexual privacy, how can age restrictions be fair anymore?

If you're really only as old as you feel, mandatory retirement ages must go. So must age group rules in sports.

If wishing or thinking makes it so, who has the right to tell any 40-year-old that he can't play on a Little League team and enjoy hitting a 12-year-old's pitches out of the park or knocking over the 13-year-old trying to tag him as he slides into third base?

For a few years Connecticut has been nervously humoring this nonsense with the rationale offered by Gov. Ned Lamont -- that it hasn't happened much, just famously in high school girls cross-country meets. This is only to say that it doesn't matter because it has happened to someone else's daughters. To object risks being called a "transphobe" or worse, though no one is denying the right of people to impersonate the other sex outside of competitive sports and bathrooms.

Similarly, people in Connecticut are being mocked or worse just for arguing that schools should not press topics like transgenderism on the youngest children.

Lacking good argument, the transgender cultists rely heavily on intimidation, because it works better. So the nonsense may not end in Connecticut until the women's basketball teams at Stanford or Tennessee recruit some 6-foot-9, 275-pound transgender forwards who leave UConn players writhing on the court with ACL tears or worse.

xxx

MORE UNPUBLIC EDUCATION: New London High School's football coach says he has been forced to resign because of an insignificant incident during a game with Ledyard High School. According to The Day of New London, the school's athletic director refuses to explain because, he says, it's a personnel matter.

That's public education in Connecticut, again resorting to the oldest non-sequitur of government -- that there never can be any accountability with personnel, so go away. Unfortunately most people do go away.

But the law does not say that personnel matters in government cannot be reviewed and discussed in public. To the contrary, while teachers enjoy a special-interest exemption for their annual performance evaluations, the law makes public other records of school employment and particularly records involving misconduct.

A request to New London's school superintendent for access to all records involving the coach might show the public what happened with him and let the public make an informed judgment about it. If the superintendent refused that much accountability, the city's Board of Education could be appealed to, and then the state Freedom of Information Commission.

School administrators might be able to delay accountability for a year or two -- probably not forever. But stalling accountability for a year or two is usually enough for public education to avoid being public.

Public education won't really be public at all until the "personnel matter" non-sequitur is challenged whenever it is cynically trotted out.

xxx

LET WINE JOIN BEER: Supermarkets in Connecticut have renewed their campaign to persuade the General Assembly and governor to change state law to let them to sell wine. That certainly would be a convenience. While supermarkets already are allowed to sell beer, anyone who would buy wine or liquor has to make a separate trip to a liquor store.

There is no good reason for this trouble, only a bad reason -- Connecticut's long subservience to the retailers and distributors of alcoholic beverages, accomplished through laws sharply limiting alcoholic-beverage retailing permits and prohibiting price competition, essentially turning the alcoholic beverage business into political patronage and what is called rent seeking. As a result Connecticut has unnecessarily high alcoholic-beverage prices.

Supermarkets should be allowed to sell beer, wine, and liquor just as liquor stores should be allowed to sell groceries -- that is, if government ever means to serve the public interest rather than the special interest

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com).

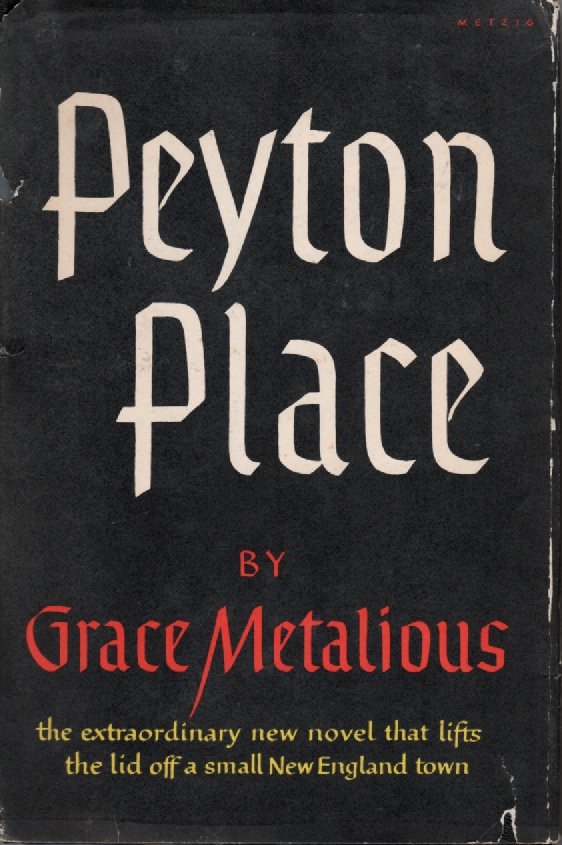

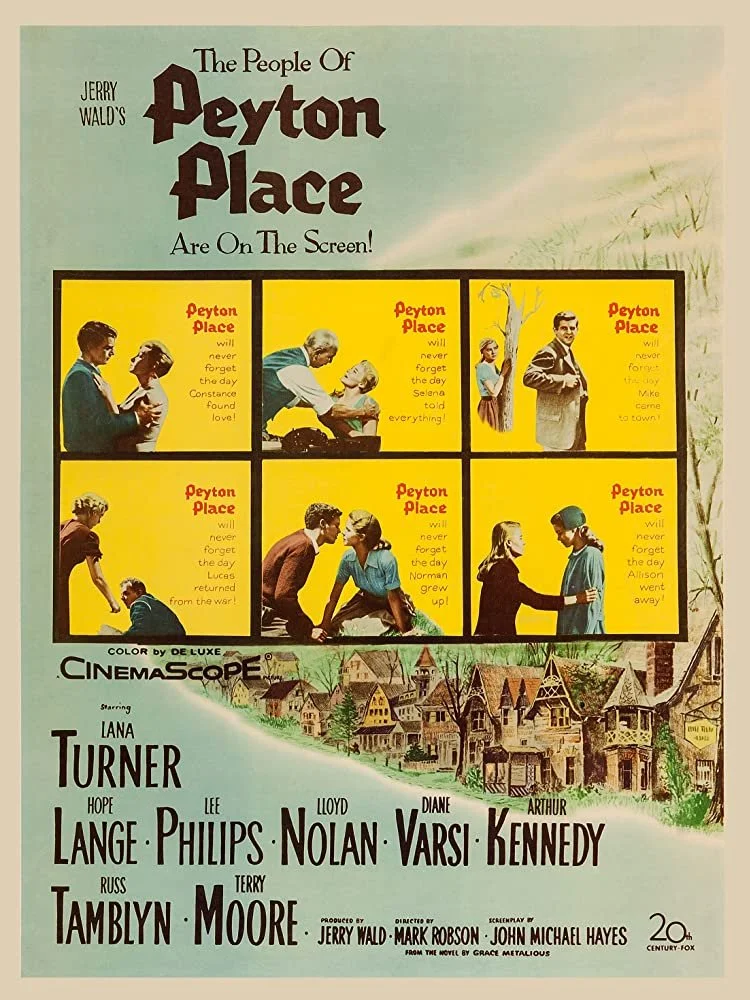

Take a left for scandal

In New Hampshire’s Lakes Region: G.I.W. refers to the village of Gilmanton Iron Works, in Gilmanton, the model for Peyton Place, the town in the once scandalous 1956 novel of the same name by Grace Metalious. Gilmanton Irons Works is named for a long-gone unprofitable mining operation.

— Photo by William Morgan

In Gilmanton: Iron Works Bridge in 1910.

Art, not anguish

“Teardrop (After Robert Irwin)” (polished stainless steel with mirror finished, halogen lighting), by Pakistani-American artist Anila Quayyum Agha, in the group show “Tradition Interrupted,” at the Lamont Gallery, at Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, N.H., through Dec. 10.

— Courtesy of Talley Dunn Gallery, in Dallas

The gallery says that each artist in this exhibition was tasked to "weave contemporary ideas with traditional art and craft," with the aim of bringing experiences of their cultures and marrying them to different mediums that complement each other.

And beware factoids

ESPN headquarters, in Bristol, Conn.

— Photo by Jkinsocal

“Part-time information and full-time opinions can be very dangerous.’’

— Chris Berman (born 1955), long-time ESPN anchor

Hit this link on why ESPN is based in Bristol.

Karen Gross: Good things have happened in higher education during the pandemic

From Wikipedia

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

It would not be the least bit unusual to feel pessimistic about education in general and higher education in particular. Enrollments have been declining at many institutions across the education landscape. Budgets are tight at many. Shootings on campuses or unexpected deaths of students are far too frequent. So too are hazing and harassment. Discrimination is on the rise. The equity gap is widening. Faculty and staff are disenchanted and stressed; so are students. Mental wellness is a challenge for many. In short, the future doesn’t look bright. And the media are having a heyday sharing all the negative news.

Yet, I still have hope.

What alternative is there? If we don’t have hope, we stagnate and fail to make forward progress. Add to this that, philosophically speaking, hope is an attitude we hold that enables us to navigate difficult times with a forward-focused approach and a belief in the possibility of a better future.

Pandemic positives

There is a third reason that I see hope in education. It has to do with what we experienced and how we responded to the pandemic. It may seem counterintuitive to many, but we need to shift the lens through which we view the pandemic’s impact on education.

Most people have been focused on the pandemic’s negatives and how we eradicate or lessen all that has happened to students. There is an embedded assumption that we need to move “back to normal” to restore what the pandemic stole.

But this assumes that education was, pre-pandemic, in good shape, which is far from the truth. Even pre-pandemic, there were deficits in education that led to student failures in college and lack of access to quality postsecondary education for far too many low-income students. Pedagogy was suboptimal in many classrooms; lecturing was too common.

Demographics also impacted educational enrollment in a period before the pandemic started. And though there were approaches being researched and tried before the pandemic to improve higher education, many of these ideas were not implemented widely or fully. For example, social and emotional learning was gaining traction as were community schools and trauma-sensitive schools. Studies showing the value of enhancing the student-teacher relationship as it improves learning and self-control were available and used by some academic institutions.

But we have ignored the positives that occurred within the education landscape, As part of a book we are co-authoring, Harvard Medical School assistant professor of psychology Edward K. S. Wang and I have gathered a wide range of positives that actually occurred during the pandemic in terms of learning and psychosocial development. Yes, there were positives although they have often not been named or recognized. And these positives have not been replicated or scaled.

Here are just a few examples of these positives. With educators working online, they were able to see students engaging with their families and that often disclosed dysfunction that, but for online learning, would not have been observed. So, in a real way, educators had an opportunity to understand more fully who their students were/are. Consider too the fact that some students who did not engage in classroom discussion when learning was in-person, were able to participate more fully and more easily online; for these students, it is likely that the absence of teasing or peer pressure were eased online. With both in-person masked and socially distant learning and in the online environment, educators exercised increased strategies to engage and connect with students as well as connecting them to each other; the absence of the “normal” engagement approaches allowed for new avenues for connection. This prompted more project-based learning, pod learning and interactive activities, all educational positives.

What if we try to identify as many of these positives as possible and reflect on how did they come about? Then we can look at how to replicate and scale these positives for the betterment of higher education moving forward.

Begin with how the positives came to pass. Think about this phrase and its applicability: Necessity is the mother of invention. We know that in times of crisis, we develop strategies to cope and deal with what is before us. We may not know why what we develop during a crisis works, but there is no question but that crises create opportunities to change the status quo. Crises force us to act quickly too, because change is afoot and will not await the traditional timetables for change.

And, that happened in education at all levels. Educators figured out–not systemically to be sure–how to teach online (some for the first time). These educators wrestled with new ways to present materials. These educators struggled to engage students who were not all in the same room–engage them with the material, engage them with one another and engage them with the educator.

Take this example. Some college students were signing into classes, but were not engaging with learning. Their names, not faces, appeared. They muted themselves. In reality, some professors did not even know if the students were “there” in terms of paying attention. Some professors realized that “teaching as usual” was not an option. There needed to be different incentives, different approaches, different forms of engagement.

While new to online platforms and learning with their colleagues, professors tried new pedagogies. Some professors tried using polling to measure learning and class engagement. Some tried using breakout rooms, allowing students to process information and solve problems. Some turned to videos within the online environment and then encouraged discussion. Some used the chat room and other writing tools, recognizing that different students had different learning styles in the online world (something that was true pre-pandemic). Some had efforts to get students to “tune” in by having true/false questions, the answers to which involved showing or not showing faces on screen. Some professors came online early and left late to enable students to ask questions. Some professors used email and online platforms to message students between classes and make connections. Some had virtual office hours. Some had phone calls with students. The ways professors made online learning work, when they were previously unaccustomed to this learning modality, was remarkable.

These are all approaches which, absent the sudden crisis and need to move online or into hybrid mode, would not have happened. Yes, online learning did exist pre-pandemic, but it was not deployed in many traditional academic environments. And, in the process of changing how they taught their students, professors experienced changes too in how they viewed their roles and responsibilities as educators. In a sense, the shared Pandemic experience allowed students and educators to engage more fully and with greater understanding of each other.

Reflect on these examples.

Some students expressed frustration with their learning through online behavior like noticeably demonstrating disinterest; they multitasked or used their cell phones or were eating and drinking, suggesting the need for a professor to engage with them offline. And, seeing this behavior encouraged some professors to pause, take note and reach out, likely because they themselves were struggling to remain engaged.

Some students were unable to connect to the materials or the class and farmed off the work to outsiders. Recognizing this risk made professors create assignments that were unique and unavailable to purchase; they also designed engagement and its impact on class grading to operate differently so that students were unable disregard in-class participation.

Some students were dysregulated or disassociated, whether online or in-person; this means they were unable to concentrate and learn as a consequence of their traumatic pandemic (or other) experience. Some of these students were angry over the change in their educational experience and wanted no part of the new offerings. Some simply checked out even though they were present. Some acted out by stomping around, throwing paper, banging on their phone, being loud and argumentative and this could be witnessed online or in person. Professors and staff had to intervene and engage differently with these students, including through interventions with staff with experience in mental wellness.

The pandemic also brought policy flexibility with experimental efforts, pilot initiatives and changes in grading and discipline. Addressing NEBHE’s fall 2022 board meeting, Inside Higher Ed’s Doug Lederman noted that after trillions of dollars in federal aid helped higher education make faster adaptations during the pandemic, now, sadly, institutions and educators are returning to the old ways. In some ways, we can see parallels to the speed with which Covid vaccines were created; federal funding, collaboration and need were compelling forces.

Here’s the point: Educators teaching during the pandemic made changes to what they did and how they did it–even if they would not have made changes but for the Pandemic’s intervention. What they did not realize or understand is that the changes they made should not be limited to the Pandemic world. They employed approaches that are valuable still: engagement; connection and communication. And these changed learning strategies are trauma-responsive, even though they likely were not used with trauma amelioration at the forefront of professors’ minds. Indeed, the trauma literature abounds with references to the need for trusted individuals, ongoing connection and increased communication.

One strategy was to visualize this change in the midst of a crisis is to reflect on the following illustration. Pre-pandemic, things were like the lower left corner of this painting, largely ordered although certainly not homogeneous. During the pandemic, things changed, and the usual rules and formats and engagement changed and we became disordered in a sense. The order pre-pandemic was disrupted. We needed professors to change; we needed students to change; we needed institutions to change. And the changes were made as we went. We built the education plane as it was flying.

What does this all mean?

We need to identify the positives that occurred in education during the pandemic. Then we need to find ways to share these positives so they can be replicated and scaled. And we need to develop stickiness— how to make change last and endure so that we can see long-term improvement. Now, stickiness is tricky; how we can make social change is a topic worthy of future discussion.

As I reflect on the positive changes engendered by the pandemic, I am struck by the statement that accompanies an ancient Japanese form of pottery repair named Kintsugi. The broken shards are pieced together with gold and then it is said, “More Beautiful for Being Broken.”

In a very real way, inspired by Kintsugi, we need to make peace with the pieces the pandemic left behind and gather the positive shards and allow them to be part of education moving forward. This following illustration that I created is an effort to speak to the beauty that can be found if we piece together what is broken. And, by analogy, so it is with education.

With the Kintsugi philosophy in mind, here is what I see. I see that positive change happened in higher education during the pandemic, and for complex reasons, we have largely ignored it. Instead, we are enamored with the negatives the pandemic produced, which are plentiful to be sure.

We would be wise to look at the positives, some of which were detailed above, that occurred–within and outside individual classrooms and within the higher education community. And we can then name what happened during the pandemic us to move forward. If we do this, we can use what we did to better education for our students today and tomorrow.

A crisis created opportunity for change. Let’s not let that opportunity go to waste to play off a hackneyed phrase. That, at the end of the day, is my hope. And it is not chimerical hope. It is hope grounded in this reality: if we are willing to work to acknowledge and then use the positive change we created, we can improve higher education.

Karen Gross is a former president of Southern Vermont College and a senior policy adviser to the U.S. Department of Education. She specializes in student success and trauma across the educational landscape and teaches at the Rutgers University School of Social Work. Her most recent book, Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door: Solutions and Strategies for Educators, PreK-College, was released in June 2020 by Columbia Teachers College Press and was the winner of the Delta Kappa Gamma Educator’s Book of the Year award.

In trouble

“I'll tell you the story. I was walking

the outer edge of the outer lands

where sporadic signs staked in dunes

warned to keep distant from the mammals;

in fact, there were critical acts in place

to enforce non-molestation,

but between me and the sea

a seal appeared to be having a time of it….’’

— From ‘“Outer Lands” {on Outer Cape Cod}, by Bill Carty

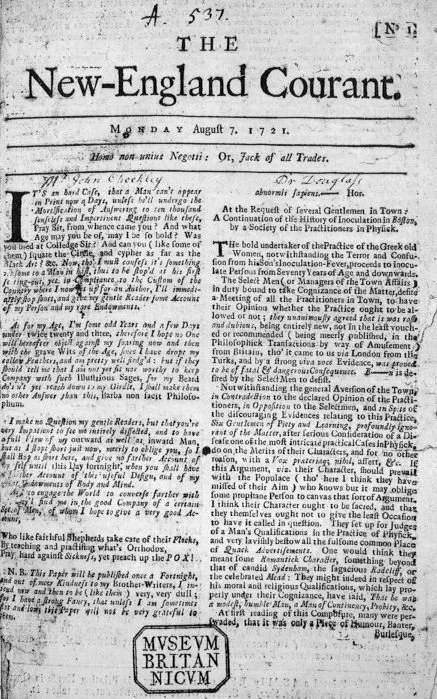

Llewellyn King: Society urgently needs mainstream news media

The front page of the Aug. 7, 1721 New England Courant, a weekly newspaper published in Boston by Benjamin Franklin’s older brother James and one of the first American newspapers.

Trying to predict the future of the Internet and to see how it might become a reliable source of fact, like old-fashioned newspaper and television reporting, is to my mind the equivalent of standing on the sand spit at Kitty Hawk, N.C., and predicting the future of aviation.

As the impact of the Internet evolved, publishers of yore wished it away. I was one of those. Although I did tell the Newsletter Publishers Association way back that putting a print story down a wire wasn’t enough; that they should develop products for this new medium.

A few were up early and caught the worm while newsletter publishers like me slept in -- notably The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and The Economist. They embraced and adjusted their offerings for the internet.

They are all publications that traditionally have had a preponderance of readers interested in issues beyond local coverage. The Wall Street Journal has always had a business audience and it adapted quickly.

The New York Times was able to leverage its global and national followers and convert them to reading online. For The Economist, there was an obvious business and world affairs audience to tap into.

The Washington Post’s Internet adoption was more dynamic.

When the Graham family sold The Post to the then-richest man in the world, Jeff Bezos, many of us believed that he was going to be another rich man buying a newspaper just to keep it going, and to reap the social opportunities that go with the franchise. But Bezos saw the future and poured money into the Post, not to keep it alive but to expand it hugely in the cyberworld. He was right and has pulled off a publishing coup.

What wasn’t seen by anyone I knew in the publishing world and isn’t in the literature, is no one understood how the internet would suck up nearly all the advertising dollars.

The pure Internet companies, peripherally in publishing, have vacuumed up the advertising, creating great wealth for their owners.

While they haven’t had a background in publishing, haven’t even thought of themselves as publishers, they have added news -- often generated by legitimate news organizations -- as a giveaway, which they haven’t paid for; if you write for a newspaper or a magazine, you have been ripped off by an Internet publisher.

The irony is that back in the 1980s and ’90s, newspaper and television properties were highly valued and selling for multiples never dreamed of. It was the time when Al Neuharth was building the Gannett chain and launching USA Today. I knew Neuharth, himself a newspaperman through and through.

Now that empire has been sold and many of its once-proud local titles are closed or look more like pamphlets than newspapers. The advertising, and with it the revenue, has gone to the Internet behemoths.

But they aren’t newspapers, and their owners aren’t publishers. They are aggregators and thanks to the wonder of the Internet, they have global presence and penetration beyond the wildest dreams of Rupert Murdoch, Conrad Black and the Sulzberger dynasty.

I salute those publications that are taking the fight to the Internet by creating daily, online editions and keeping the craft-of-old alive.

These include The New Yorker and The Spectator, an English magazine trying to get an American presence.

On a recent visit to Edinburgh, my wife and I ducked into a newsagent, the traditional British shop that sells newspapers, magazines and sundries, to buy some newspapers. Hanging above the shop’s entrance was a large blue sign advertising The Scotsman. The owner told my wife that he didn’t sell newspapers anymore, and nobody needed to read them.

If you know that there is a war going on in Ukraine, it is because the traditional media has told you so; because brave reporters are there on the spot, not online. Repeat this line for Iran, China, Mexico to say nothing of Washington, Toronto, London, Rome, Moscow and Beijing.

We need the old media, often called the mainstream media. We earned that moniker. The Hill, Axios and Politico show where journalism might be headed nationally. But who will cover the statehouse, the school board, and the courts? In the dark, all those institutions stray.

In a courthouse in Prince William County, Va., I asked about press coverage. The woman showing me around sighed and said, “We used to have reporters, they even had their own table, but not anymore.” Lady Justice had closed one eye.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Not for kindling

“Untitled”’ (wooden sticks), by Charles Arnoldi, in the show “On the Edge: Los Angeles Art 1970s-1990s,’’ at the Armenian Museum, Watertown, Mass., through Feb. 26.

Amidst climate change, treating cold-stunned sea turtles in Mass.

An Atlantic Ridley sea turtle

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report

BOSTON

The New England Aquarium has reported an increase in treatment for hypothermic sea turtles. The number of cold-stunned sea turtles found in Massachusetts has been steadily increasing for the past 20 years. Warmer ocean temperatures during the fall have delayed sea-turtle migrations and indicate climate change’s effect on the New England.

The New England Aquarium and its partners have surveyed the beaches around Cape Cod to find turtles and transport them to the aquarium’s Sea Turtle Hospital for treatment. Once the turtles arrive at the hospital, they are given a physical exam to determine the best course of treatment. Staff at the hospital say most of the turtles are severely dehydrated and have pneumonia. Each turtle receives a custom treatment to ensure that they are given the appropriate amount of time to recover before they return to the ocean.

The healing process can take weeks to years depending on the severity of the turtle’s condition. In total, the hospital has treated 170 turtles this season; this includes 133 critically endangered Atlantic Ridley turtles and 37 green turtles.

The director of animal health at the New England Aquarium, Dr. Charles Innis, said, “All of our sea turtle patients receive individualized care based on their condition. Depending on the severity, turtles may need weeks, months, and sometimes more than a year of treatment before they are at a point where we can clear them for release back into the ocean.”

A reason not to miss beach days

Nantasket Beach, in Hull, Mass., in 1953, with the now long-closed Paragon Park amusement park across the road.

Like all times, 'historic’

“American Negroes, A Handbook” (acrylic and collage on canvas), by Massachusetts writer Karmimadeebora McMillan, in the show ‘‘Hard Times,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Jan. 5-Jan. 29.

The gallery says:

“We live through unprecedented and historic times, and future generations will look back and ask us; who were we and what did we do during the past few years? The selection of artworks in this exhibition, ‘Hard Times,’ focuses on the COVID-19 pandemic, racial justice, economic inequity and climate crisis. Out of instability, fragility, and mortality must come solidarity, strength, and life. This show offers us an opportunity to come together and intentionally reflect on our current moment to hold ourselves accountable.’’

Mythological Massachusetts

“I was brought up in southern Massachusetts, where it was thought that mythology was a subject that we should all grasp. It was very much a part of my education. The easiest way to parse the world is through mythology.”

―John Cheever (1912-1982), famed short-story writer and novelist. He grew up in the then-genteel Wollaston section of Quincy, Mass. While he spent most of his adult life in New York City and its Westchester County suburbs, much of his work is sited in Boston’s South Shore suburbs. He is buried in one of them — Norwell, with some of his ancestors.

“Quincy, Massachusetts” (oil on canvas), by Childe Hassam, 1892.

David Warsh: Tech presbyopia helped cause crypto apocalypse

Number of Bitcoin transactions per month (logarithmic scale)

“Valhalla in Flames,’’ by Max Bruckner.

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

I have paid little attention to the collapse of crypto-mania because, since it has been clear all along that it was a fraud perpetrated on the greedy and gullible by a coterie of tech-savvy young.

The so-called crypto currencies were simply unregulated banks, their accounting dubious, their lending practices opaque, their valuations in public markets jacked up to preposterous heights by leverage. As Wall Street Journal columnist Greg Ip wrote in a piece published Nov. 27

While bankruptcy filings aren’t entirely clear, they describe many of the largest creditors as customers or other crypto-related companies. Crypto companies, in other words, operate in a closed loop, deeply interconnected within that loop but with few apparent connections of significance to traditional finance. This explains how an asset class once worth roughly $3 trillion could lose 72% of its value, and prominent intermediaries could go bust, with no discernible spillovers to the financial system.

Block chain technology, on the other hand, has interested me ever since Bitcoin, in 2008, introduced its possibilities to the modern world. Interested, that is, but not enough to do much about it.

It is no accident that the best timeline on the inspiration behind block chain technology I could quickly find last week was published by the Institute of Charters Accountants of England and Wales (ICAEW). That is because the ICAEW, with its 150,000 well-compensated members, and their counterparts enrolled in similar organizations around the world, represent the profession of trusted book-keepers whose livelihoods are threatened in some degree by the new digital technology. Threatened someday, that is – not all at once, but eventually, in 10 to 20 years.

Nor is it surprising that the ICAEW is pretty good on the details of the invention of the threat to the accountancy profession. (Here is a slightly more informative version.) A couple more clicks led to this highly readable digest, The little-known history of block chain, as told by its inventors, by Greg Hall, on a Bitcoin Association Web site.

It turns out that the inventors of the technology behind block chain were working for Bellcore, descendent of the old Bell Laboratories, owned in 1991 by the seven Baby Bells, when they began discussing how it might be possible to time-stamp a digital document. Stuart Haber had a PhD in computer science from Columbia University, Scott Stornetta was a Stanford-trained physicist. They shared an interest in cryptography, a lively topic at the time.

Stornetta knew how easy it was to doctor a digital document without anyone noticing. Society depends on trustworthy records – that is where the bookkeepers came in. But if a transition to entirely digital documents was inevitable, the problem was to create immutable records.

Haber and Stornetta figured out how. Hall writes, “The solution was to use one-way hash functions, take requests for registration of documents (which mean the hash values of the documents), group them into ‘units’ (blocks), build the Merkle tree and create a linked chain of hash values.” They presented their work to an international cryptology conference in Santa Barbara; block chain was born. For a better feel for the inventors, and the work that they did, watch the 10-minute YouTube interview at the end of Hall’s piece.

In 1998 a reclusive Hungarian computer scientist and lawyer named Nick Szabo began experimenting with a digital currency he called Bit Gold. In 2000, German cryptologist and software engineer Stefan Konst published a theory of cryptographically secured chains of data.

But only in 2008 did developers, working under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto, publish a workable model of a distributed ledger by then known as block chain. Bitcoin, the killer application, appeared the next year. And in 2014, a block chain 2.0 version was separated from the Bitcoin asset and offered for other kinds of transactions-reporting applications. By then cloud computing was a fact. The human block chain – the accounting profession with their ledgers and books – had been put on notice. Audit robots? Not so fast!

The Bitcoin world, though a reality, is still thronged with crypto-market evangelicals. To get out of it, I turned to Distributed Ledgers: Design and Regulation of Financial Infrastructure and Payment Systems (MIT, 2020), by Robert Townsend, a professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Townsend is a remarkable scholar. A general equilibrium theorist, trained at the University of Minnesota, he taught at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Chicago for 30 years.

In 1993, he published The Medieval Village Economy: A Study of the Pareto Mapping in General Equilibrium Models (Princeton.) and, in 1997, began his continuing Thailand Project (sample paper: The Village Money Market Revealed: Credit Chains and Shadow Banking). By 2021, he spent a year as the senior research fellow at the Bank for International Settlements, the central bankers’ central bank,” in Basel, Switzerland. And when disparate central bank digital currencies, with their distributed ledgers, are eventually stitched together, that is where the reconciliation will take place.

The cryptocurrency craze, a fraud of memorable proportions, was based on an acute case of what the legendary economic historian Paul David decades ago labeled technological presbyopia – the tendency to see clearly events as they will be, far ahead in time, while overlooking all the necessary steps to get there. For a sense of how long it takes for a new discovery to realize its full technological potential, read Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Crucial Technology (Scribner, 2022), by Chris Miller. Look for a similarly highly readable a book about distributed ledgers to appear in, say, another thirty years.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.