Vox clamantis in deserto

Karen Gross: Good things have happened in higher education during the pandemic

From Wikipedia

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

It would not be the least bit unusual to feel pessimistic about education in general and higher education in particular. Enrollments have been declining at many institutions across the education landscape. Budgets are tight at many. Shootings on campuses or unexpected deaths of students are far too frequent. So too are hazing and harassment. Discrimination is on the rise. The equity gap is widening. Faculty and staff are disenchanted and stressed; so are students. Mental wellness is a challenge for many. In short, the future doesn’t look bright. And the media are having a heyday sharing all the negative news.

Yet, I still have hope.

What alternative is there? If we don’t have hope, we stagnate and fail to make forward progress. Add to this that, philosophically speaking, hope is an attitude we hold that enables us to navigate difficult times with a forward-focused approach and a belief in the possibility of a better future.

Pandemic positives

There is a third reason that I see hope in education. It has to do with what we experienced and how we responded to the pandemic. It may seem counterintuitive to many, but we need to shift the lens through which we view the pandemic’s impact on education.

Most people have been focused on the pandemic’s negatives and how we eradicate or lessen all that has happened to students. There is an embedded assumption that we need to move “back to normal” to restore what the pandemic stole.

But this assumes that education was, pre-pandemic, in good shape, which is far from the truth. Even pre-pandemic, there were deficits in education that led to student failures in college and lack of access to quality postsecondary education for far too many low-income students. Pedagogy was suboptimal in many classrooms; lecturing was too common.

Demographics also impacted educational enrollment in a period before the pandemic started. And though there were approaches being researched and tried before the pandemic to improve higher education, many of these ideas were not implemented widely or fully. For example, social and emotional learning was gaining traction as were community schools and trauma-sensitive schools. Studies showing the value of enhancing the student-teacher relationship as it improves learning and self-control were available and used by some academic institutions.

But we have ignored the positives that occurred within the education landscape, As part of a book we are co-authoring, Harvard Medical School assistant professor of psychology Edward K. S. Wang and I have gathered a wide range of positives that actually occurred during the pandemic in terms of learning and psychosocial development. Yes, there were positives although they have often not been named or recognized. And these positives have not been replicated or scaled.

Here are just a few examples of these positives. With educators working online, they were able to see students engaging with their families and that often disclosed dysfunction that, but for online learning, would not have been observed. So, in a real way, educators had an opportunity to understand more fully who their students were/are. Consider too the fact that some students who did not engage in classroom discussion when learning was in-person, were able to participate more fully and more easily online; for these students, it is likely that the absence of teasing or peer pressure were eased online. With both in-person masked and socially distant learning and in the online environment, educators exercised increased strategies to engage and connect with students as well as connecting them to each other; the absence of the “normal” engagement approaches allowed for new avenues for connection. This prompted more project-based learning, pod learning and interactive activities, all educational positives.

What if we try to identify as many of these positives as possible and reflect on how did they come about? Then we can look at how to replicate and scale these positives for the betterment of higher education moving forward.

Begin with how the positives came to pass. Think about this phrase and its applicability: Necessity is the mother of invention. We know that in times of crisis, we develop strategies to cope and deal with what is before us. We may not know why what we develop during a crisis works, but there is no question but that crises create opportunities to change the status quo. Crises force us to act quickly too, because change is afoot and will not await the traditional timetables for change.

And, that happened in education at all levels. Educators figured out–not systemically to be sure–how to teach online (some for the first time). These educators wrestled with new ways to present materials. These educators struggled to engage students who were not all in the same room–engage them with the material, engage them with one another and engage them with the educator.

Take this example. Some college students were signing into classes, but were not engaging with learning. Their names, not faces, appeared. They muted themselves. In reality, some professors did not even know if the students were “there” in terms of paying attention. Some professors realized that “teaching as usual” was not an option. There needed to be different incentives, different approaches, different forms of engagement.

While new to online platforms and learning with their colleagues, professors tried new pedagogies. Some professors tried using polling to measure learning and class engagement. Some tried using breakout rooms, allowing students to process information and solve problems. Some turned to videos within the online environment and then encouraged discussion. Some used the chat room and other writing tools, recognizing that different students had different learning styles in the online world (something that was true pre-pandemic). Some had efforts to get students to “tune” in by having true/false questions, the answers to which involved showing or not showing faces on screen. Some professors came online early and left late to enable students to ask questions. Some professors used email and online platforms to message students between classes and make connections. Some had virtual office hours. Some had phone calls with students. The ways professors made online learning work, when they were previously unaccustomed to this learning modality, was remarkable.

These are all approaches which, absent the sudden crisis and need to move online or into hybrid mode, would not have happened. Yes, online learning did exist pre-pandemic, but it was not deployed in many traditional academic environments. And, in the process of changing how they taught their students, professors experienced changes too in how they viewed their roles and responsibilities as educators. In a sense, the shared Pandemic experience allowed students and educators to engage more fully and with greater understanding of each other.

Reflect on these examples.

Some students expressed frustration with their learning through online behavior like noticeably demonstrating disinterest; they multitasked or used their cell phones or were eating and drinking, suggesting the need for a professor to engage with them offline. And, seeing this behavior encouraged some professors to pause, take note and reach out, likely because they themselves were struggling to remain engaged.

Some students were unable to connect to the materials or the class and farmed off the work to outsiders. Recognizing this risk made professors create assignments that were unique and unavailable to purchase; they also designed engagement and its impact on class grading to operate differently so that students were unable disregard in-class participation.

Some students were dysregulated or disassociated, whether online or in-person; this means they were unable to concentrate and learn as a consequence of their traumatic pandemic (or other) experience. Some of these students were angry over the change in their educational experience and wanted no part of the new offerings. Some simply checked out even though they were present. Some acted out by stomping around, throwing paper, banging on their phone, being loud and argumentative and this could be witnessed online or in person. Professors and staff had to intervene and engage differently with these students, including through interventions with staff with experience in mental wellness.

The pandemic also brought policy flexibility with experimental efforts, pilot initiatives and changes in grading and discipline. Addressing NEBHE’s fall 2022 board meeting, Inside Higher Ed’s Doug Lederman noted that after trillions of dollars in federal aid helped higher education make faster adaptations during the pandemic, now, sadly, institutions and educators are returning to the old ways. In some ways, we can see parallels to the speed with which Covid vaccines were created; federal funding, collaboration and need were compelling forces.

Here’s the point: Educators teaching during the pandemic made changes to what they did and how they did it–even if they would not have made changes but for the Pandemic’s intervention. What they did not realize or understand is that the changes they made should not be limited to the Pandemic world. They employed approaches that are valuable still: engagement; connection and communication. And these changed learning strategies are trauma-responsive, even though they likely were not used with trauma amelioration at the forefront of professors’ minds. Indeed, the trauma literature abounds with references to the need for trusted individuals, ongoing connection and increased communication.

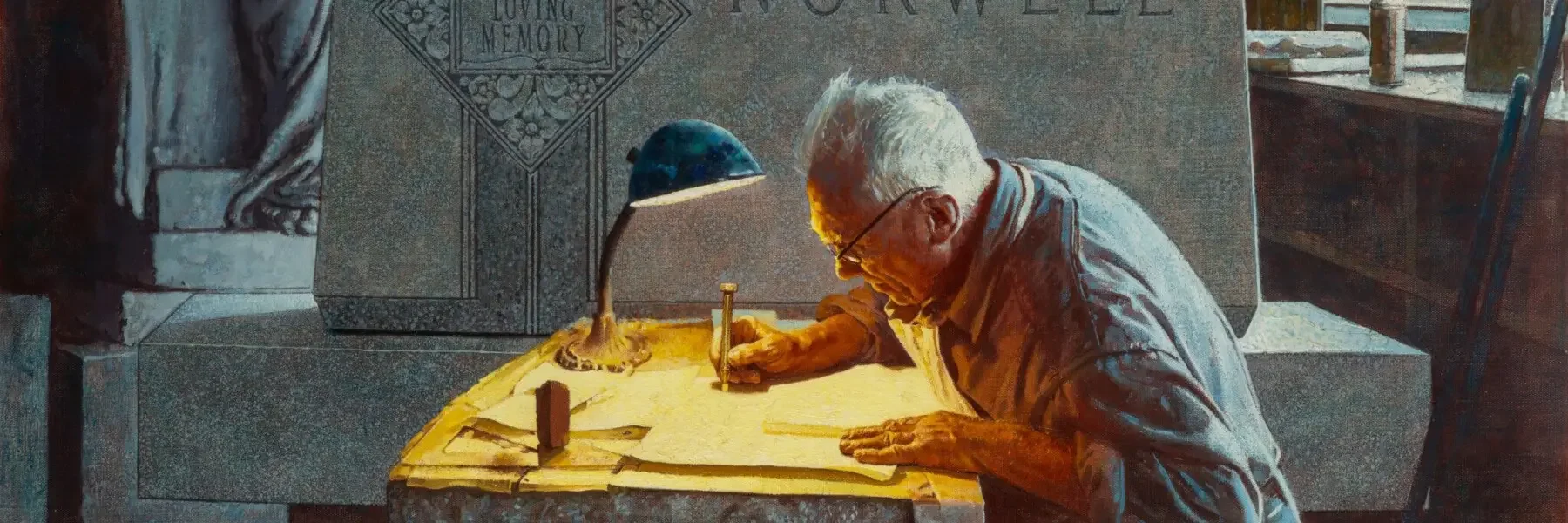

One strategy was to visualize this change in the midst of a crisis is to reflect on the following illustration. Pre-pandemic, things were like the lower left corner of this painting, largely ordered although certainly not homogeneous. During the pandemic, things changed, and the usual rules and formats and engagement changed and we became disordered in a sense. The order pre-pandemic was disrupted. We needed professors to change; we needed students to change; we needed institutions to change. And the changes were made as we went. We built the education plane as it was flying.

What does this all mean?

We need to identify the positives that occurred in education during the pandemic. Then we need to find ways to share these positives so they can be replicated and scaled. And we need to develop stickiness— how to make change last and endure so that we can see long-term improvement. Now, stickiness is tricky; how we can make social change is a topic worthy of future discussion.

As I reflect on the positive changes engendered by the pandemic, I am struck by the statement that accompanies an ancient Japanese form of pottery repair named Kintsugi. The broken shards are pieced together with gold and then it is said, “More Beautiful for Being Broken.”

In a very real way, inspired by Kintsugi, we need to make peace with the pieces the pandemic left behind and gather the positive shards and allow them to be part of education moving forward. This following illustration that I created is an effort to speak to the beauty that can be found if we piece together what is broken. And, by analogy, so it is with education.

With the Kintsugi philosophy in mind, here is what I see. I see that positive change happened in higher education during the pandemic, and for complex reasons, we have largely ignored it. Instead, we are enamored with the negatives the pandemic produced, which are plentiful to be sure.

We would be wise to look at the positives, some of which were detailed above, that occurred–within and outside individual classrooms and within the higher education community. And we can then name what happened during the pandemic us to move forward. If we do this, we can use what we did to better education for our students today and tomorrow.

A crisis created opportunity for change. Let’s not let that opportunity go to waste to play off a hackneyed phrase. That, at the end of the day, is my hope. And it is not chimerical hope. It is hope grounded in this reality: if we are willing to work to acknowledge and then use the positive change we created, we can improve higher education.

Karen Gross is a former president of Southern Vermont College and a senior policy adviser to the U.S. Department of Education. She specializes in student success and trauma across the educational landscape and teaches at the Rutgers University School of Social Work. Her most recent book, Trauma Doesn’t Stop at the School Door: Solutions and Strategies for Educators, PreK-College, was released in June 2020 by Columbia Teachers College Press and was the winner of the Delta Kappa Gamma Educator’s Book of the Year award.

In trouble

“I'll tell you the story. I was walking

the outer edge of the outer lands

where sporadic signs staked in dunes

warned to keep distant from the mammals;

in fact, there were critical acts in place

to enforce non-molestation,

but between me and the sea

a seal appeared to be having a time of it….’’

— From ‘“Outer Lands” {on Outer Cape Cod}, by Bill Carty

Llewellyn King: Society urgently needs mainstream news media

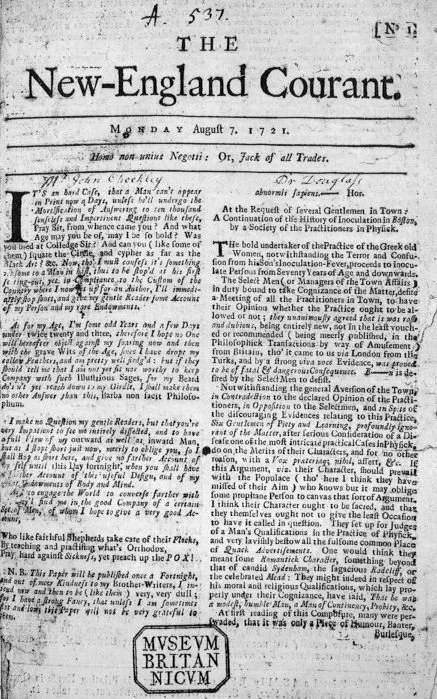

The front page of the Aug. 7, 1721 New England Courant, a weekly newspaper published in Boston by Benjamin Franklin’s older brother James and one of the first American newspapers.

Trying to predict the future of the Internet and to see how it might become a reliable source of fact, like old-fashioned newspaper and television reporting, is to my mind the equivalent of standing on the sand spit at Kitty Hawk, N.C., and predicting the future of aviation.

As the impact of the Internet evolved, publishers of yore wished it away. I was one of those. Although I did tell the Newsletter Publishers Association way back that putting a print story down a wire wasn’t enough; that they should develop products for this new medium.

A few were up early and caught the worm while newsletter publishers like me slept in -- notably The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and The Economist. They embraced and adjusted their offerings for the internet.

They are all publications that traditionally have had a preponderance of readers interested in issues beyond local coverage. The Wall Street Journal has always had a business audience and it adapted quickly.

The New York Times was able to leverage its global and national followers and convert them to reading online. For The Economist, there was an obvious business and world affairs audience to tap into.

The Washington Post’s Internet adoption was more dynamic.

When the Graham family sold The Post to the then-richest man in the world, Jeff Bezos, many of us believed that he was going to be another rich man buying a newspaper just to keep it going, and to reap the social opportunities that go with the franchise. But Bezos saw the future and poured money into the Post, not to keep it alive but to expand it hugely in the cyberworld. He was right and has pulled off a publishing coup.

What wasn’t seen by anyone I knew in the publishing world and isn’t in the literature, is no one understood how the internet would suck up nearly all the advertising dollars.

The pure Internet companies, peripherally in publishing, have vacuumed up the advertising, creating great wealth for their owners.

While they haven’t had a background in publishing, haven’t even thought of themselves as publishers, they have added news -- often generated by legitimate news organizations -- as a giveaway, which they haven’t paid for; if you write for a newspaper or a magazine, you have been ripped off by an Internet publisher.

The irony is that back in the 1980s and ’90s, newspaper and television properties were highly valued and selling for multiples never dreamed of. It was the time when Al Neuharth was building the Gannett chain and launching USA Today. I knew Neuharth, himself a newspaperman through and through.

Now that empire has been sold and many of its once-proud local titles are closed or look more like pamphlets than newspapers. The advertising, and with it the revenue, has gone to the Internet behemoths.

But they aren’t newspapers, and their owners aren’t publishers. They are aggregators and thanks to the wonder of the Internet, they have global presence and penetration beyond the wildest dreams of Rupert Murdoch, Conrad Black and the Sulzberger dynasty.

I salute those publications that are taking the fight to the Internet by creating daily, online editions and keeping the craft-of-old alive.

These include The New Yorker and The Spectator, an English magazine trying to get an American presence.

On a recent visit to Edinburgh, my wife and I ducked into a newsagent, the traditional British shop that sells newspapers, magazines and sundries, to buy some newspapers. Hanging above the shop’s entrance was a large blue sign advertising The Scotsman. The owner told my wife that he didn’t sell newspapers anymore, and nobody needed to read them.

If you know that there is a war going on in Ukraine, it is because the traditional media has told you so; because brave reporters are there on the spot, not online. Repeat this line for Iran, China, Mexico to say nothing of Washington, Toronto, London, Rome, Moscow and Beijing.

We need the old media, often called the mainstream media. We earned that moniker. The Hill, Axios and Politico show where journalism might be headed nationally. But who will cover the statehouse, the school board, and the courts? In the dark, all those institutions stray.

In a courthouse in Prince William County, Va., I asked about press coverage. The woman showing me around sighed and said, “We used to have reporters, they even had their own table, but not anymore.” Lady Justice had closed one eye.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email address is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Not for kindling

“Untitled”’ (wooden sticks), by Charles Arnoldi, in the show “On the Edge: Los Angeles Art 1970s-1990s,’’ at the Armenian Museum, Watertown, Mass., through Feb. 26.

Amidst climate change, treating cold-stunned sea turtles in Mass.

An Atlantic Ridley sea turtle

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report

BOSTON

The New England Aquarium has reported an increase in treatment for hypothermic sea turtles. The number of cold-stunned sea turtles found in Massachusetts has been steadily increasing for the past 20 years. Warmer ocean temperatures during the fall have delayed sea-turtle migrations and indicate climate change’s effect on the New England.

The New England Aquarium and its partners have surveyed the beaches around Cape Cod to find turtles and transport them to the aquarium’s Sea Turtle Hospital for treatment. Once the turtles arrive at the hospital, they are given a physical exam to determine the best course of treatment. Staff at the hospital say most of the turtles are severely dehydrated and have pneumonia. Each turtle receives a custom treatment to ensure that they are given the appropriate amount of time to recover before they return to the ocean.

The healing process can take weeks to years depending on the severity of the turtle’s condition. In total, the hospital has treated 170 turtles this season; this includes 133 critically endangered Atlantic Ridley turtles and 37 green turtles.

The director of animal health at the New England Aquarium, Dr. Charles Innis, said, “All of our sea turtle patients receive individualized care based on their condition. Depending on the severity, turtles may need weeks, months, and sometimes more than a year of treatment before they are at a point where we can clear them for release back into the ocean.”

A reason not to miss beach days

Nantasket Beach, in Hull, Mass., in 1953, with the now long-closed Paragon Park amusement park across the road.

Like all times, 'historic’

“American Negroes, A Handbook” (acrylic and collage on canvas), by Massachusetts writer Karmimadeebora McMillan, in the show ‘‘Hard Times,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Jan. 5-Jan. 29.

The gallery says:

“We live through unprecedented and historic times, and future generations will look back and ask us; who were we and what did we do during the past few years? The selection of artworks in this exhibition, ‘Hard Times,’ focuses on the COVID-19 pandemic, racial justice, economic inequity and climate crisis. Out of instability, fragility, and mortality must come solidarity, strength, and life. This show offers us an opportunity to come together and intentionally reflect on our current moment to hold ourselves accountable.’’

Mythological Massachusetts

“I was brought up in southern Massachusetts, where it was thought that mythology was a subject that we should all grasp. It was very much a part of my education. The easiest way to parse the world is through mythology.”

―John Cheever (1912-1982), famed short-story writer and novelist. He grew up in the then-genteel Wollaston section of Quincy, Mass. While he spent most of his adult life in New York City and its Westchester County suburbs, much of his work is sited in Boston’s South Shore suburbs. He is buried in one of them — Norwell, with some of his ancestors.

“Quincy, Massachusetts” (oil on canvas), by Childe Hassam, 1892.

David Warsh: Tech presbyopia helped cause crypto apocalypse

Number of Bitcoin transactions per month (logarithmic scale)

“Valhalla in Flames,’’ by Max Bruckner.

SOMERVILLE, MASS.

I have paid little attention to the collapse of crypto-mania because, since it has been clear all along that it was a fraud perpetrated on the greedy and gullible by a coterie of tech-savvy young.

The so-called crypto currencies were simply unregulated banks, their accounting dubious, their lending practices opaque, their valuations in public markets jacked up to preposterous heights by leverage. As Wall Street Journal columnist Greg Ip wrote in a piece published Nov. 27

While bankruptcy filings aren’t entirely clear, they describe many of the largest creditors as customers or other crypto-related companies. Crypto companies, in other words, operate in a closed loop, deeply interconnected within that loop but with few apparent connections of significance to traditional finance. This explains how an asset class once worth roughly $3 trillion could lose 72% of its value, and prominent intermediaries could go bust, with no discernible spillovers to the financial system.

Block chain technology, on the other hand, has interested me ever since Bitcoin, in 2008, introduced its possibilities to the modern world. Interested, that is, but not enough to do much about it.

It is no accident that the best timeline on the inspiration behind block chain technology I could quickly find last week was published by the Institute of Charters Accountants of England and Wales (ICAEW). That is because the ICAEW, with its 150,000 well-compensated members, and their counterparts enrolled in similar organizations around the world, represent the profession of trusted book-keepers whose livelihoods are threatened in some degree by the new digital technology. Threatened someday, that is – not all at once, but eventually, in 10 to 20 years.

Nor is it surprising that the ICAEW is pretty good on the details of the invention of the threat to the accountancy profession. (Here is a slightly more informative version.) A couple more clicks led to this highly readable digest, The little-known history of block chain, as told by its inventors, by Greg Hall, on a Bitcoin Association Web site.

It turns out that the inventors of the technology behind block chain were working for Bellcore, descendent of the old Bell Laboratories, owned in 1991 by the seven Baby Bells, when they began discussing how it might be possible to time-stamp a digital document. Stuart Haber had a PhD in computer science from Columbia University, Scott Stornetta was a Stanford-trained physicist. They shared an interest in cryptography, a lively topic at the time.

Stornetta knew how easy it was to doctor a digital document without anyone noticing. Society depends on trustworthy records – that is where the bookkeepers came in. But if a transition to entirely digital documents was inevitable, the problem was to create immutable records.

Haber and Stornetta figured out how. Hall writes, “The solution was to use one-way hash functions, take requests for registration of documents (which mean the hash values of the documents), group them into ‘units’ (blocks), build the Merkle tree and create a linked chain of hash values.” They presented their work to an international cryptology conference in Santa Barbara; block chain was born. For a better feel for the inventors, and the work that they did, watch the 10-minute YouTube interview at the end of Hall’s piece.

In 1998 a reclusive Hungarian computer scientist and lawyer named Nick Szabo began experimenting with a digital currency he called Bit Gold. In 2000, German cryptologist and software engineer Stefan Konst published a theory of cryptographically secured chains of data.

But only in 2008 did developers, working under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto, publish a workable model of a distributed ledger by then known as block chain. Bitcoin, the killer application, appeared the next year. And in 2014, a block chain 2.0 version was separated from the Bitcoin asset and offered for other kinds of transactions-reporting applications. By then cloud computing was a fact. The human block chain – the accounting profession with their ledgers and books – had been put on notice. Audit robots? Not so fast!

The Bitcoin world, though a reality, is still thronged with crypto-market evangelicals. To get out of it, I turned to Distributed Ledgers: Design and Regulation of Financial Infrastructure and Payment Systems (MIT, 2020), by Robert Townsend, a professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Townsend is a remarkable scholar. A general equilibrium theorist, trained at the University of Minnesota, he taught at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Chicago for 30 years.

In 1993, he published The Medieval Village Economy: A Study of the Pareto Mapping in General Equilibrium Models (Princeton.) and, in 1997, began his continuing Thailand Project (sample paper: The Village Money Market Revealed: Credit Chains and Shadow Banking). By 2021, he spent a year as the senior research fellow at the Bank for International Settlements, the central bankers’ central bank,” in Basel, Switzerland. And when disparate central bank digital currencies, with their distributed ledgers, are eventually stitched together, that is where the reconciliation will take place.

The cryptocurrency craze, a fraud of memorable proportions, was based on an acute case of what the legendary economic historian Paul David decades ago labeled technological presbyopia – the tendency to see clearly events as they will be, far ahead in time, while overlooking all the necessary steps to get there. For a sense of how long it takes for a new discovery to realize its full technological potential, read Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Crucial Technology (Scribner, 2022), by Chris Miller. Look for a similarly highly readable a book about distributed ledgers to appear in, say, another thirty years.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

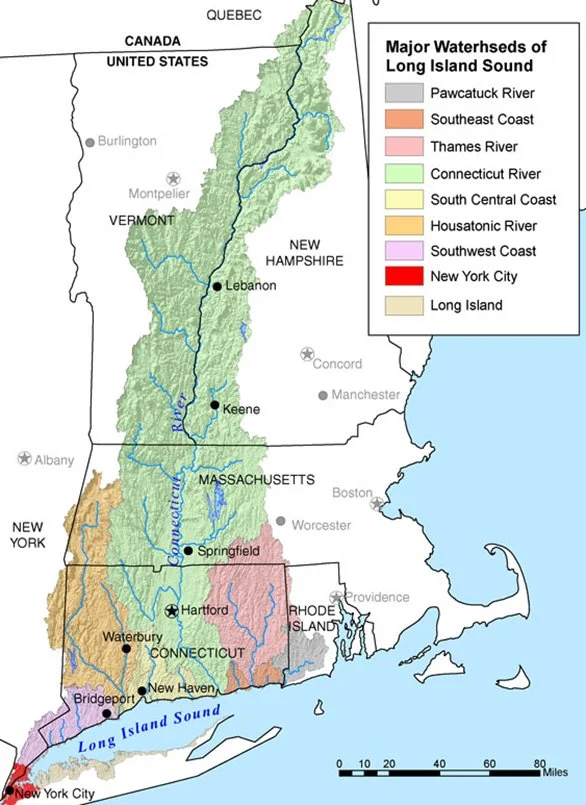

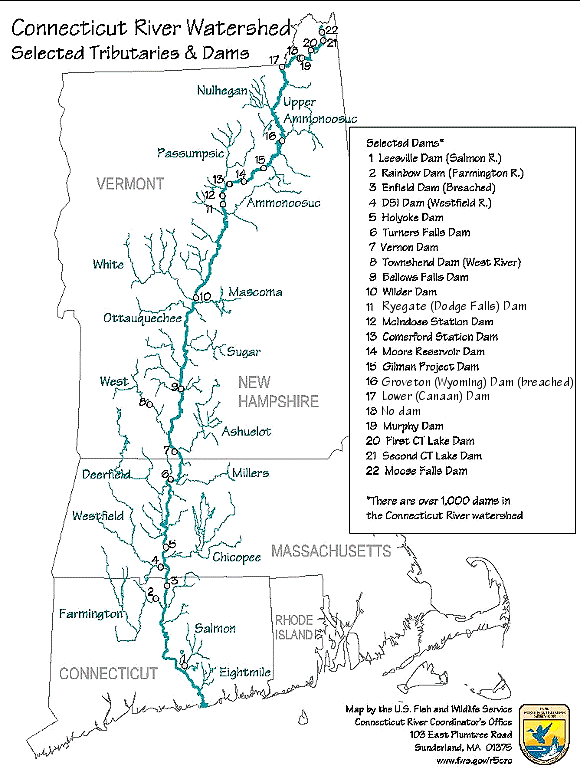

Frank Carini: Connecticut River ecosystem is much healthier these days but still threatened

— American Rivers map

Text from ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A recuperating natural world borders and lives in the only major river in the Northeast without a large port, harbor or urban area at its mouth. It provides drinking water to millions and supports recreational uses and important fisheries.

But 57 years ago actress Katharine Hepburn called the Connecticut River “the world’s most beautifully landscaped cesspool.”

By the mid-1960s, the longest river in New England, at 410 miles, had served as the region’s industrial- and human-waste sewer for more than a century. It had been unsafe for recreational use since the early 1900s, according to Ellsworth Grant’s 2006 book , Connecticut Disasters.

Hartford’s Park River, also known as Hog River, a tributary that used to deliver waste into the Connecticut River, was buried in the 1940s, in large part because it was so polluted, according to Walter Woodward, Connecticut’s state historian from 2004 until his retirement this year.

The Connecticut River deposits silt as it flows into Long Island Sound.

In 1965, Hepburn, who had a home in the Fenwick section of Old Saybrook at the mouth of the river, narrated a half-hour documentary called The Long Tidal River about the polluting of the Connecticut River. The title was taken from the Algonquian peoples of southern New England who have called the Connecticut River the “long tidal river” for hundreds of years.

The Hepburn-narrated film reportedly helped spark an environmental movement in New England that called for building more wastewater- treatment facilities and placing tighter restrictions on polluting industries. The film and its money quote also prompted state and federal government to adopt laws to clean up the Connecticut River and many other waterways similarly polluted.

In 1967, the Connecticut Legislature passed a Clean Water Act, and five years later the federal government passed its own Clean Water Act.

“The river was really dirty and polluted. We’ve seen an amazing amount of progress in the last 50 years,” said Kelsey Wentling, the Massachusetts river steward for the Connecticut River Conservancy (CRC). “I’ve spoken with people who never touched or came near it as kids but now swim and fish in the river.”

Drift boat fishing guide working the Connecticut river near Colebrook, N.H., in the steam’s upper riches during the brief summer up there.

— Photo by Mike Cline

More than a half-century of increased awareness and pollution-control efforts have transformed the Connecticut River — which flows through four of New England’s six states, from the Canadian border to Long Island Sound — from a sewer system to a national symbol of environmental restoration. The river and its tributaries have received several federal designations for their wild and scenic nature and for their importance to the region’s cultural heritage.

The Nature Conservancy has called the river’s estuary “one of the world’s last great places.” The river’s vast watershed — about 77 percent is forested, 9 percent agricultural, 7 percent wetlands, and 7 percent developed, according to the Army Corps of Engineers — is home to federally threatened and endangered species such as the piping plover, the puritan tiger beetle, dwarf wedgemussel, Jesup’s milk-vetch, and northeastern bulrush. Its also the critical lifeline for the 40,000-acre Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge.

In 1997, the Connecticut River was designated an “American Heritage River” in recognition of its “distinctive natural, economic, agricultural, scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational qualities.”

Fifteen years later, in 2012, the U.S. Department of the Interior named it America’s first National Blueway. The program, however, designed to recognize conservation efforts along the nation’s waterways, was dissolved two years later amid opposition from landowners and politicians who feared that it would lead to increased regulations and possible land seizures. The Connecticut River remains the country’s only National Blueway.

Despite the river’s metamorphosis from dead zone to one swimming with alewife, American and hickory shad, blueback herring, smallmouth bass, striped bass and three species of trout, the Connecticut River still remains among the most extensively dammed rivers in the country. More than a thousand dams dot its tributaries and 16 dams span its mainstem, 12 of which are hydropower projects.

It, like most U.S. waterways, is vulnerable to pollution from stormwater runoff carrying fertilizers, pesticides, agricultural waste, and hydrocarbons. Fish advisories are in place for sections of the river, swimming is discouraged after heavy rains, and the river’s sediment is still plagued by a legacy of contamination.

While farming and logging brought significant ruination to the Connecticut River watershed before the 19th Century, industrialization in the 1800s accelerated the destruction. Industries diverted the natural flow of the river to generate power and dumped all kinds of waste into it.

By the beginning of the 20th Century, agricultural runoff from commercial farming — in particular, the area’s thriving tobacco industry — further polluted the river. By the time that World War II ended, the use of new chemical dyes and pesticides had added to the river’s ruination.

CRC, formerly the Connecticut River Watershed Council, has been addressing these issues since the early 1950s. Last year the Greenfield, Mass.-based nonprofit completed five years of work to improve the health of the Connecticut River and Long Island Sound.

The work was part of a $10 million partnership grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to promote conservation of the Long Island Sound watershed. CRC focused on reducing pollution in the Connecticut River, which contributes about 70 percent of the fresh water to Long Island Sound.

CRC completed 58 river-restoration projects covering more than 180 miles and 60 acres in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Vermont. The projects were designed to help reduce erosion, runoff, and excess nitrogen, which cause low dissolved oxygen levels that threaten fish and other aquatic organisms.

The work included planting trees and shrubs along rivers on agricultural lands to slow runoff and filter pollutants from water before it enters waterways; berm and dam removals that restore natural river flows and decrease erosion during floods; and streambank stabilization to keep soil in place.

One problem that remains, especially in the Connecticut portion of the river, Wentling said is invasive species such as water thyme and water chestnut creating a “monoculture mat” that is crowding out native plants and animals.

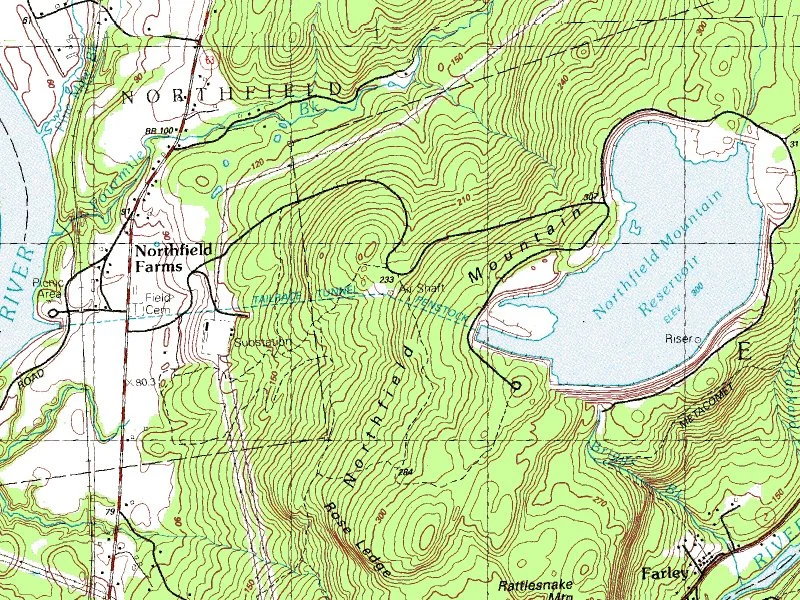

One of the bigger threats — beyond sewage overflows from wastewater- treatment facilities during heavy rains — remaining on the Connecticut River system, or at least a section of it, is FirstLight’s Northfield Mountain Pumped Storage Station, a hydroelectric generating facility and reservoir in Franklin County, Mass. Fossil fuels are used to pump water up to the reservoir on the hill. Wentling said it takes more energy to move the water up than is created when it is released back down. The banked energy in the reservoir is used when energy prices are high or there is a spike in demand.

Besides burning natural gas to create future hydropower, the power plant is “killing” countless fish and other aquatic organisms, according to longtime Connecticut River defender Karl Meyer.

In a Nov. 3 opinion piece published in VTDigger, the Greenfield, Mass., resident wrote, “The Northfield station is the deadliest machine ever installed on New England’s Great River. It sucks in endless streams of the Connecticut’s flow at 15,000 cubic feet per second for hours — the equivalent of eight three-bedroom homes filled with aquatic life every second, inhaling over 28,000 fish houses an hour.”

He noted that American shad are just one of two dozen species exposed to that daily suction. “For those other species, what’s undisputed is none of their millions of untallied eggs, adults and young survive the trip through Northfield either.”

Meyer, who said this problem has been ignored for decades, has been writing about issues affecting the Connecticut River for years. He has concentrated his efforts on the needs of the river’s fish, with a particular concern for American shad and the shortnose sturgeon, an endangered species.

FirstLight’s renewal process for a Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) license is expected to begin by the end of the year. Meyer, for one, isn’t happy it has taken four years to get to this point.

“FirstLight now operates the Northfield Mountain Pumped Storage Station via its series of FERC license delay requests while its venture capital shareholders and CEOs profit off an expired 2018 license,” he wrote.

He’s concerned the “license disastrously poised to re-enshrine Northfield’s horrific impacts for decades.”

Wentling said the climate crisis, from drought to bursts of extreme rainfall, is exacerbating the stress that the Connecticut River remains under, and it’s only going to get worse.

Frank Carini is co-founder and senior reporter for ecoRI News.

Judith Martin: Should elderly patients risk surgery?

“What older patients want to know is, ‘What’s my life going to look like?’ But we haven’t been able to answer with data of this quality before.”

— Zara Cooper, M.D., professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and the director of the Center for Geriatric Surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Nearly 1 in 7 older adults die within a year of undergoing major surgery, according to an important new study that sheds much-needed light on the risks seniors face when having invasive procedures.

Especially vulnerable are older patients with probable dementia (33% die within a year) and frailty (28%), as well as those having emergency surgeries (22%). Advanced age also amplifies risk: Patients who were 90 or older were six times as likely to die than those ages 65 to 69.

The study in JAMA Surgery, published by researchers at the Yale School of Medicine, addresses a notable gap in research: Though patients 65 and older undergo nearly 40% of all surgeries in the U.S., detailed national data about the outcomes of these procedures has been largely missing.

“As a field, we’ve been really remiss in not understanding long-term surgical outcomes for older adults,” said Dr. Zara Cooper, a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and the director of the Center for Geriatric Surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Of particular importance is information about how many seniors die, develop disabilities, can no longer live independently, or have a significantly worsened quality of life after major surgery.

In the new study, Dr. Thomas Gill and Yale colleagues examined claims data from traditional Medicare and survey data from the National Health and Aging Trends study spanning 2011 to 2017. (Data from private Medicare Advantage plans was not available at that time but will be included in future studies.)

Invasive procedures that take place in operating rooms with patients under general anesthesia were counted as major surgeries. Examples include procedures to replace broken hips, improve blood flow in the heart, excise cancer from the colon, remove gallbladders, fix leaky heart valves, and repair hernias, among many more.

Older adults tend to experience more problems after surgery if they have chronic conditions such as heart or kidney disease; if they are already weak or have difficulty moving around; if their ability to care for themselves is compromised; and if they have cognitive problems, noted Gill, a professor of medicine, epidemiology, and investigative medicine at Yale.

Two years ago, Gill’s team conducted research that showed 1 in 3 older adults had not returned to their baseline level of functioning six months after major surgery. Most likely to recover were seniors who had elective surgeries for which they could prepare in advance.

In another study, published last year in the Annals of Surgery, his team found that about 1 million major surgeries occur in individuals 65 and older each year, including a significant number near the end of life. Remarkably, data documenting the extent of surgery in the older population has been lacking until now.

“This opens up all kinds of questions: Were these surgeries done for a good reason? How is appropriate surgery defined? Were the decisions to perform surgery made after eliciting the patient’s priorities and determining whether surgery would achieve them?” said Dr. Clifford Ko, a professor of surgery at the University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine and director of the Division of Research and Optimal Patient Care at the American College of Surgeons.

As an example of this kind of decision-making, Ko described a patient who, at 93, learned he had early-stage colon cancer on top of preexisting liver, heart and lung disease. After an in-depth discussion and being told that the risk of poor results was high, the patient decided against invasive treatment.

“He decided he would rather take the risk of a slow-growing cancer than deal with a major operation and the risk of complications,” Ko said.

Still, most patients choose surgery. Dr. Marcia Russell, a staff surgeon at the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, described a 90-year-old patient who recently learned he had colon cancer during a prolonged hospital stay for pneumonia. “We talked with him about surgery, and his goals are to live as long as possible,” said Russell. To help prepare the patient, now recovering at home, for future surgery, she recommended he undertake physical therapy and eat more high-protein foods, measures that should help him get stronger.

“He may need six to eight weeks to get ready for surgery, but he’s motivated to improve,” Russell said.

The choices that older Americans make about undergoing major surgery will have broad societal implications. As the 65-plus population expands, “covering surgery is going to be fiscally challenging for Medicare,” noted Dr. Robert Becher, an assistant professor of surgery at Yale and a research collaborator with Gill. Just over half of Medicare spending is devoted to inpatient and outpatient surgical care, according to a 2020 analysis.

What’s more, “nearly every surgical subspecialty is going to experience workforce shortages in the coming years,” Becher said, noting that in 2033, there will be nearly 30,000 fewer surgeons than needed to meet expected demand.

These trends make efforts to improve surgical outcomes for older adults even more critical. Yet progress has been slow. The American College of Surgeons launched a major quality improvement program in July 2019, eight months before the covid-19 pandemic hit. It requires hospitals to meet 30 standards to achieve recognized expertise in geriatric surgery. So far, fewer than 100 of the thousands of hospitals eligible are participating.

One of the most advanced systems in the country, the Center for Geriatric Surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital illustrates what’s possible. There, older adults who are candidates for surgery are screened for frailty. Those judged to be frail consult with a geriatrician, undergo a thorough geriatric assessment, and meet with a nurse who will help coordinate care after discharge.

Also initiated are “geriatric-friendly” orders for post-surgery hospital care. This includes assessing older patients three times a day for delirium (an acute change in mental status that often afflicts older hospital patients), getting patients moving as soon as possible, and using non-narcotic pain relievers. “The goal is to minimize the harms of hospitalization,” said Cooper, who directs the effort.

She told me about a recent patient, whom she described as a “social woman in her early 80s who was still wearing skinny jeans and going to cocktail parties.” This woman came to the emergency room with acute diverticulitis and delirium; a geriatrician was called in before surgery to help manage her medications and sleep-wake cycle, and recommend non-pharmaceutical interventions.

With the help of family members who visited this patient in the hospital and have remained involved in her care, “she’s doing great,” Cooper said. “It’s the kind of outcome we work very hard to achieve.”

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

‘Realistic memories’ and dreams

“In Winter” (cast resin), by Memy Ish-Shalom, in his show “Dreams and Memories, ‘‘ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Dec. 2-Jan. 8. He’s an immigrant from Israel now living in Newton, Mass.

He says:

“My sculptures are an artistic response to realistic memories and to dreams or daydreams. But sometimes dreams turn into memories and memories become dreams.

“I reflect on childhood memories of being a son to my father and adult memories of being a father to my son. I also reflect on the deep sorrow that grew from losing my father.’’

Money just for education and transport?

Will the “millionaires tax’’ drive any of the rich folks living in fancy streets like this on Boston’s Beacon Hill to move their official residences to Florida or New Hampshire?

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Massachusetts voters, by a 52-48 percent margin, approved what’s been dubbed “the millionaires’ tax’’ in the Nov. 8 election.

The Bay State has had a flat rate of 5 percent of federal adjusted gross income. A new constitutional amendment will add an additional 4 percent tax on taxable income over $1 million, starting in 2023, in a modest move to progressive taxation. (Federal taxation has progressive elements and unprogressive ones, the latter including shielding more income from capital gains than from earned income, favoritism that benefits the affluent.)

A Tufts University study projects that the “millionaires’ tax’’ will bring in about $1.3 billion next year, and that the levy would only affect 0.6 percent of households.

Proponents promise that all the money to be raised by the new tax would go to education and transportation. If that actually happens, it could strengthen the commonwealth’s – and New England’s – economy. Despite all the promotion of the Sun Belt’s tax systems – good for the rich, but not particularly for the poor and middle class, which are saddled with highly regressive sales taxes in these mostly Red States – the wealthiest states continue to be those willing to pay for good public services.

But would a recession, causing Massachusetts’s state tax revenues to fall, end up forcing the state to use much, or all, of that $1.3 billion to balance its budget? Could well happen next year in the predicted recession because there’s nothing to legally compel officials to spend the money just on schools and transportation (presumably mostly the MBTA, including trains to and from Rhode Island).

In any event, because of the new tax, a few rich folks will leave, and/or threaten to leave, the Bay State to go to Florida, that paradise of income-tax avoiders, money launderers, gigantic, floodable oceanside mansions, inland tarpaper shacks, big donors to GOPQ campaigns, 7-Elevens, terrifyingly wide intersections and Burmese pythons, or to, say, New Hampshire, which prospers in no small degree because it’s next to the great wealth creator of Greater Boston, in a state that’s willing to pay for extensive public services that support that wealth creation.

(While New Hampshire famously has no income or sales tax, it relies very heavily on property taxes. About 65 percent of government revenues come from property taxes – the highest dependence on such levies in the U.S.)

By the way, eight of the ten states most dependent on federal money are GOPQ-dominated and seven of the nine states that send more to the Feds than they receive are Democrat-dominated. But maybe that will change as people move around.

Bella DeVaan: Swift superfans may have struck blow against monopoly

Taylor Swift’s fans paid for the singer’s mansion — the white Colonial Revival structure at the top of the hill —- in the Watch Hill section of Westerly, R.I. The house, called High Watch, was formerly named Holiday House and also called the Harkness House (after a family enriched by Standard Oil who lived there for a time) by locals, is an 11,000-square-foot edifice on five acres that she bought for $17.75 million in 2013. The house was built in 1929-1930.

— Photo by JJBers - https://www.flickr.com/photos/jjbers/33980495256/

Via OtherWords.org

As the cost of food, travel, and gifts complicate holiday plans across the country, millions of Americans have been awakened to the sinister power of monopolies.

But now there are exciting new possibilities to rein them in.

This November, legions of new anti-monopolists were born. They’re Taylor Swift’s superfans — and they just might be the reason the government breaks up Ticketmaster.

Hoping to get pre-sale tickets to their favorite pop star’s upcoming tour, millions of “Swifties” waited in endless electronic queues, only to be hit with sky-high prices and exorbitant fees — if they were able to snag a ticket at all.

“Ticket prices may fluctuate, upon demand, at any time,” read an ominous warning on the Ticketmaster website.

And they did: Under Ticketmaster’s “dynamic pricing” system, fans reported ticket prices running up to thousands of dollars — not including hefty fees. Prices spiked even higher on the secondary resale market. On StubHub, ticket listings reached upwards of $95,000.

Finally, Ticketmaster threw in the towel and canceled subsequent presale windows. Their site crashed thousands of times. It was mayhem — and thanks to an unchecked monopoly, fans had no other option.

But the Swifties struck back. Hours after Taylor Swift released a statement apologizing to fans and chastising Ticketmaster, the Department of Justice (DOJ) announced an investigation of Live Nation Entertainment, which owns Ticketmaster.

While their investigation wasn’t prompted by Swift, reported the New York Times, Swifties’ wave of discontent was overwhelming enough to warrant the department’s public disclosure. Immediately after, the company that had been bragging about a record-smashing 2022 saw its stock plummet.

How did we get here? When it comes to antitrust issues, the U.S. government has essentially been asleep at the wheel, allowing Ticketmaster’s monopoly to crush its competition for over a decade.

In 2010, Ticketmaster and Live Nation merged into Live Nation Entertainment. The merger was subject to a relatively weak consent decree, which asked the merged companies not to abuse their live venue dominance. But it’s been easy for Live Nation Entertainment to intimidate their naysayers and flout guidelines.

“Ticketmaster bullies venues into not working with their competitors,” explains Chokepoint Capitalism author Cory Doctorow. “They bully smaller artists by denying them management. They bully big artists by controlling their ticket prices and letting their fans down. And they bully their customers into paying exorbitant prices for tickets.”

Well before the Swift fiasco, a coalition of research organizations and live event workers launched the Break Up Ticketmaster campaign asking the Department of Justice to “investigate and unwind” the live events monopoly. The campaign quickly gained ground, generating tens of thousands of signatures on an advocacy letter.

Policy makers are now echoing that call.

“Consumers deserve better than this anti-hero behavior,” tweeted Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), punning off a song from Swift’s latest album, Midnights.

And on MSNBC, Senate Antitrust Committee chair Amy Klobuchar (D.-Minn.) promised a Senate hearing. She’s also co-authored bills with Senators Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Mike Lee (R-Utah) to facilitate antitrust enforcement with new filing, funding, and state empowerment rules.

The attorney general of Tennessee — home to the “angriest Swifties” — opened an investigation into Ticketmaster’s misconduct, too.

President Biden recently directed his administration to “reduce or eliminate” junk fees like Ticketmasters’ infamous extra charges, which sometimes total up to 78 percent of the cost of a ticket. He’s also appointed a passel of antitrust enforcers and signed a robust, competition-oriented executive order in his first months in the Oval Office.

Monopolies aren’t just fleecing concert-goers. All of us experience the villainy of monopolies — in the high price of a tight seat on a plane, in the destruction of local journalism, in skyrocketing monthly rent and food prices, or in the marginalization of small online businesses.

So, present day monopolists, steel yourselves and remember: When you provoke a superfan, they’ll come for you.Bella DeVaan

Bella DeVaan is a program associate at the Institute for Policy Studies and a co-editor of Inequality.org.

The end

“The hills are in gray.

Someone will kick.

Someone will hold.

The year has grown old…..

An overcast day.

A sweet, sad day.

They’re leaving the stands.’’

— From “Fall Overcast,’’ by E.B. White (1899-1985), famed essayist, children’s book author and minor poet. He lived much of his life on a small farm on the Maine Coast.

Chris Powell: More accountability needed from chronic criminals, too

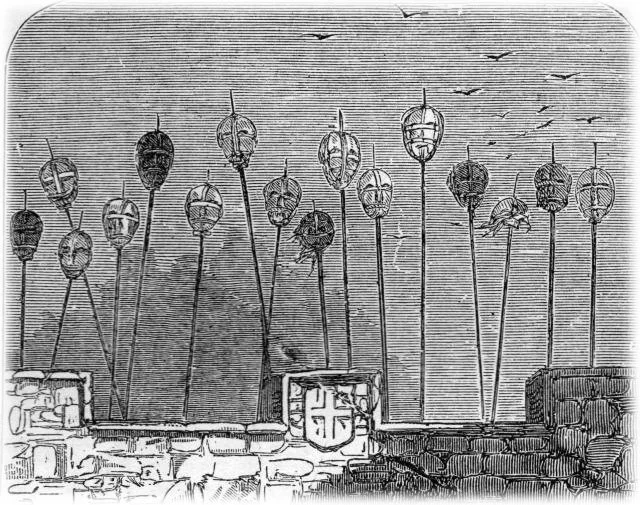

The spiked heads of executed criminals once adorned the gatehouse of the medieval London Bridge.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut state government lately has tried to increase the accountability of police officers, equipping more of them with dashboard and body cameras, establishing the office of inspector general to investigate police use of force, and diminishing the immunity of officers from lawsuits for actions on duty.

But strangely state government has done nothing to increase the accountability of criminals, even as serious crimes have increased and many are committed by chronic offenders who never should have been let out of prison. Many crimes by chronic offenders have been well publicized but the governor and state legislators seem to pay no attention.

Odds are that an especially horrible case involving a chronic offender this month will be ignored officially as well. That is, the man charged and being sought in connection with the murder of his baby girl in Naugatuck, Conn., has a serious criminal record -- drug dealing, assault and resisting arrest -- for which he served time in prison, and, the Waterbury Republican-American says, at the time of the murder was both on parole and free on bonds totaling $375,000 on new charges of carjacking, assault, robbery and burglary.

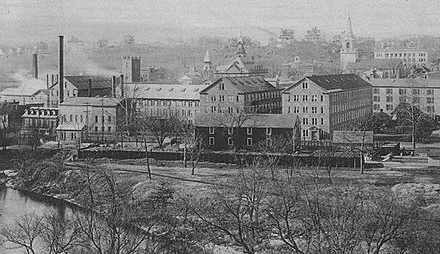

Goodyear Metallic Rubber Shoe Company, in downtown Naugatuck (c. 1890).

Of course, the suspect in the baby's murder hasn't been convicted of it yet. Even so, given his record of convictions and the additional serious charges that already were pending against him, someone in authority should be asking why he was free on both parole and bonds for new crimes and why prosecution of his pending charges was not hastened. When someone has been killed and the suspect is a career criminal, the case should be worth at least a hearing before a General Assembly committee.

Yes, police should be held more accountable. But how about courts, prosecutors, probation officers, and social workers and therapists who work with criminals who reoffend?

Accountability is still lacking in the case of Henryk Gudelski, the jogger who last year was run down and killed in New Britain, Conn., by a stolen car allegedly driven by a 17-year-old boy who had been arrested 13 times in the preceding 3½ years but had been repeatedly freed by juvenile court.

The governor and legislature have never taken note of that case either, and no accountability has been achieved by their recent legislation allowing police to detain arrested juveniles for an extra two hours while seeking a detention order from a judge. While the governor and legislators touted the change, police say it is no practical help.

Indeed, instead of dealing with chronic offenders, the criminal justice issue gaining momentum in Connecticut seems to be faster restoration of voting rights to felons. How "woke"!

If only "woke" really meant having awakened to what's going on.

xxx

OPEN PRIMARY MISCHIEF: While he is no friend of Republicans, columnist and talk-radio host Colin McEnroe says he has the remedy for the party's poor performance in Connecticut: open primaries. If unaffiliated voters were allowed to help choose Republican candidates, McEnroe writes, the party would not nominate extreme conservatives who can't win. McEnroe cites Connecticut's two most recent Republican governors, John G. Rowland and Jodi Rell, as proof that Connecticut will elect Republicans.

But Rowland and Rell were not extreme conservatives. They were hardly conservatives at all, and they were nominated without open primaries.

Besides, open primaries are undemocratic because they can impair like-minded people from maintaining a party, and they invite mischief like what recently occurred around the country as Democrats intervened in Republican nominations, assisting candidates associated with former President Donald Trump because they would be easier to defeat. This intervention by non-Republicans helped nominate the less electable Republican candidates.

Connecticut Republicans could restrict their open primaries to unaffiliated voters, nominally excluding Democrats. But in Connecticut changing registration from a party to unaffiliated and back is easy and quick, so mischief in open primaries would be easy too.

Of course, Democrats in Connecticut long have been winning elections without open primaries -- indeed, often without any primaries at all. So maybe the ability to dispense a lot of government patronage is more helpful than open primaries.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

Llewellyn King: How over-complexity might bring down electricity and other key systems

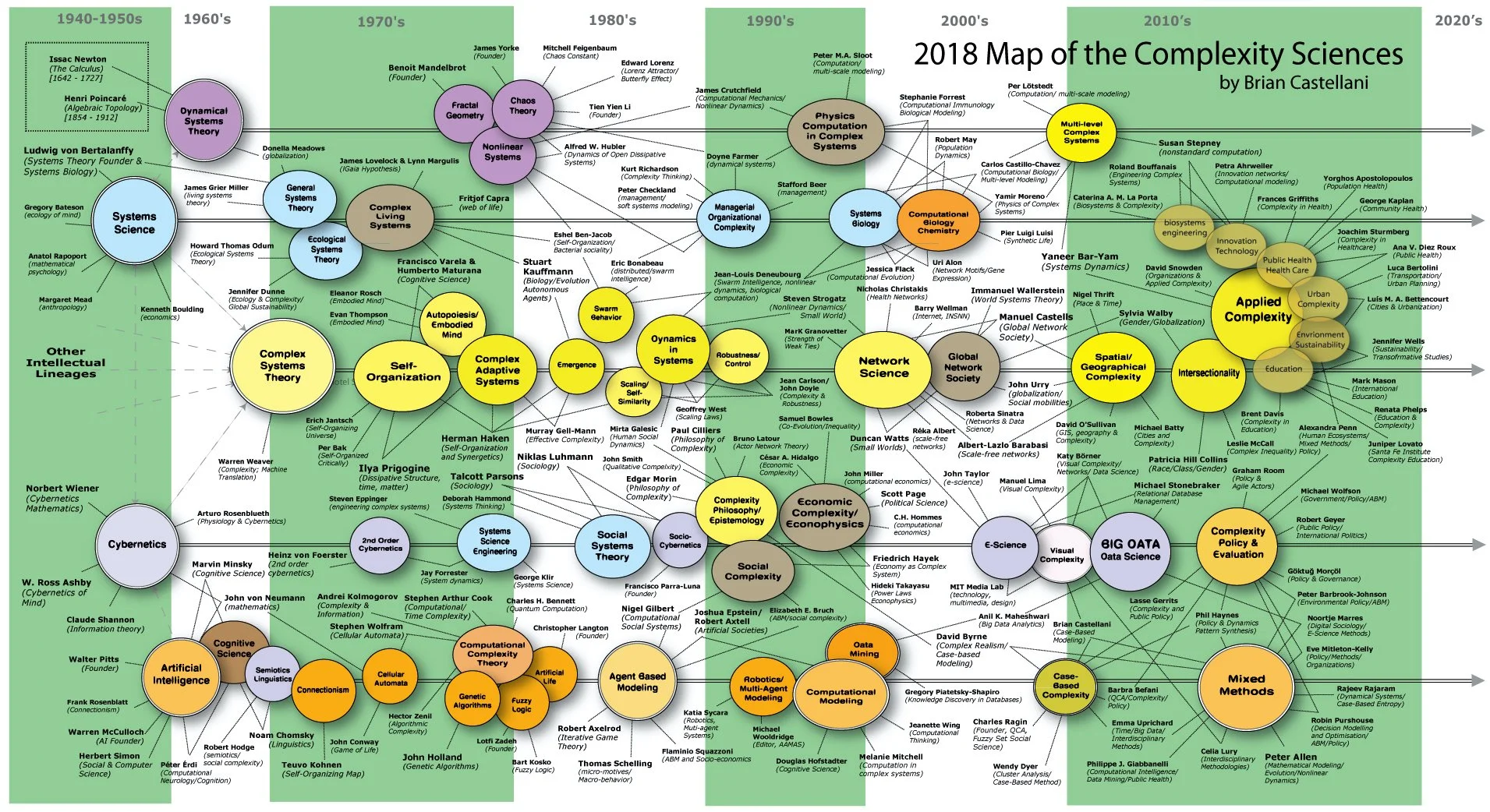

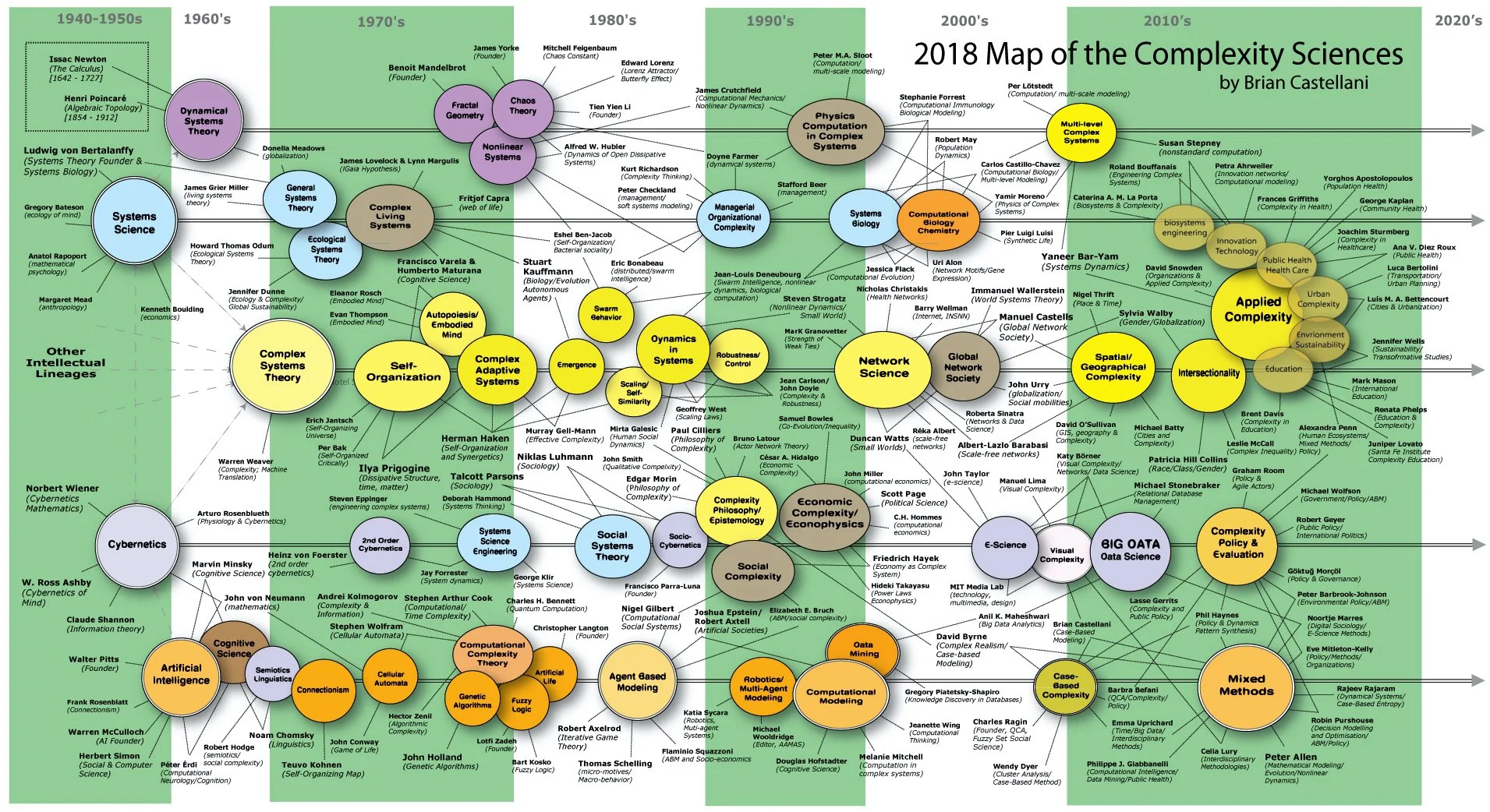

A perspective on the development of complexity science.

Graphic by Brian Castellani

Has the Internet of things — the vast, interconnected, computer-centered ecosystem of today — reached a point where it is so complex, so multilayered, has so many architects, and has so many national interests embedded in it that it has become a threat to itself?

Will the electric grid, the financial system or the air-traffic control apparatus implode not by the hand of a malicious hacker but because the system — which is now systems of systems — has become the most subtle threat it faces?

Worse, as the speed of telephony increases with 5G, will that speed up the system implosion with devastating consequences?

Will this technological meltdown be triggered from within by a long-forgotten piece of code, a failed sensor or inferior products in vital, load-bearing points in this system?

This kind of disaster from complexity is known as “emergent behavior.” Remember that concept. Likely, you will hear a lot about it going forward.

Emergent behavior is what happens when various objects or substances come together and trigger a reaction that can’t be predicted, nor can the trigger be predetermined.

Robert Gardner, founder and principal at New World Technology Partners and a National Security Agency consultant, tells me that the computer ecosystem is highly subject to emergent behavior in the so-called complex, adaptive system of systems which is today’s cyberworld. It is a world which has been built over time with new layers of complexity added willy-nilly as computing, and what has been asked of it, has become a huge, impregnable structure, beyond the reach of its present-day architects and minders, including cybersecurity aficionados.

In at The Creation

Gardner, to my mind, is worth listening to because he was, if you will, in at the beginning. At least, he was on hand and worked on the computer evolution, starting in the 1970s when he helped build the first supercomputers and has consulted with various national laboratories, including Lawrence Livermore and Los Alamos. He has also played a key role in the development of today’s super-sophisticated financial computing infrastructure, known as “fintech.”

Gardner says of emergent behaviors in complex systems, “They can’t be predicted by examining individual components of a system as they are produced by the system as a whole — facilitating a perfect storm that conspires to produce catastrophe.”

Complexity is the new adversary, he says of these huge, virtual systems of systems.

Gardner adds, “The complexity adversary does not require outside assistance; it can be summoned by minor user, environmental or equipment failures, or timing instabilities in the ordinary operation of a system.

“Current threat detection software does not seek or detect these system conditions, leaving them highly vulnerable.”

Gardner cites two examples where the system failed itself. The first example is when a tree branch that fell on a power line in Ohio set in motion a blackout across Michigan, New York and much of Canada in 2003. The system became the problem: It went berserk, and 50 million people lost power.

The second example is how something called “counter-party risk” sped the demise of Lehman Brothers, the Wall Street colossus. That was when a single default embedded in the system initiated the implosion of the whole structure.

No Nefarious Actors

Of these, Gardner says, “There were no nefarious actors to defend against; the complex, heterogeneous nature of the systems themselves led to emergent behaviors.”

Going forward, the best practices in cyber hygiene won’t defend against catastrophe. The entwined systems are their own enemy. Utilities take note.

And the danger may get worse, according to Gardner.

The villain is 5G: the super-fast phone and data system now being deployed across the country. It will come in what are called “slices,” but for that you can read stages.

. Slice one is what is being built out now: It is faster than today’s 4G, which is what phones and data use currently. It features mobile broadband.

· Slice two, called “machine to machine,” is faster yet.

· Slice three will move vast quantities of data at astounding speeds which, if the data is damaging to the system and has occurred at an unidentifiable location, represents a threat to a whole tranche of human activity.

Self-destroying machines will be unstoppable when they have 5G slice three to speed bad information throughout their system and connected systems. Tech Armageddon.

Llewellyn King, a veteran columnist, editor, publisher and international energy consultant, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of "White House Chronicle" on PBS.

Read this column on:

White House Chronicle

Forbes

Buy art to support refugees

“Colibri” (lithograph), by Somerville, Mass.-based Phyllis Ewan, in the show “Kingston Members: Celebrate Renewal,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Nov. 30-Dec. 24.

— Photo courtesy Kingston Gallery

Colibri refers to a species of hummingbird

In this show, Kingston Gallery members present a variety of work in a multitude of mediums. The show's mission is to "renew our connection to art and to celebrate community after years marked by pandemic and ongoing conflict." The gallery encourages the public to come ready to buy art off the walls to support the Boston Medical Center's Immigrant and Refugee Health Center.

John Harney: Many thanks, New England

John O. Harney

From, The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

In October, I wrote to NEBHE colleagues to let them know I would be retiring from the organization and the editorship of its New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE) in early January 2023.

While NEBHE has been my job, NEJHE has been my passion. I joined NEBHE in 1988 and, in 1990, became editor of NEJHE (then called Connection: New England’s Journal of Higher Education and Economic Development).

Thirty-four years for one outlet. Sometimes I forget I’m even that old.

I looked at the journal editions, printed on paper until 2010, as pieces of art (albeit imperfect ones) as much as a news service. The best issues I thought were like our own “Sgt. Pepper’’ album. Today, reminds me a bit of Bob Dylan’s “Maggie’s Farm.’’

I’ll miss working with our distinguished authors, sometimes goading them into writing their bylined commentaries—usually for no fee. Those writers also happened to be our readers … a community of policymakers, practitioners and regionalists we described variously as “opinion leaders” in the old days, “thought leaders” more recently. All bound together by an interest in higher education and New England (which I recall was a tough audience to quantify for analytically retentive advertisers).

I’ll also miss the editorial “departments” we developed, such as Data Connection, a sort of spinoff of the Harper’s Magazine Index, but with a New England and higher education flavor. Reflective of a certain “NEJHE Beat,” these items—like a lot of NEJHE content—track along a unique constellation of issues anchored in higher education but also moored to social justice, economic and workforce development, regional cooperation, quality of life, academic research, workplaces and other topics that, together, say New Englandness.

In our print days, I was especially invested in my Editor’s Memo columns that opened every edition from 1990 to 2010.

A few of these Editor’s Memos noted the transition from Connection to NEJHE, an illness that forced me to take leave in 2007 and the journal’s shift from print to all-Web in 2010.

Many pieces looked at the future of New England. One touched on our mock Race for Governor of the State of New England. That exercise helped midwife New England Online, an attempt by NEBHE and partners to take advantage of then-new networking technologies to provide something of a clearinghouse of all things New England—a bit unfocused perhaps, but poignant in a region where, the “winner” of that fantastic New England governor’s race, then state Rep. Arnie Arnesen of New Hampshire, quipped that the capital of New England should not be, say, Boston or Hartford, but instead something along the lines of “www.ne.gov.” (See our house ad.)

The House that Jack Built focused on the first NEBHE president I worked with, Jack Hoy, who passed away in 2013. Jack was a mentor who pioneered understanding of the profound nexus between higher education and economic development that is now taken for granted and that served as the basis for the journal’s name, Connection.

Among other of these commentaries and columns, several focused on the magical relationship between higher-education institutions and their host communities. Even in the emerging age of a placeless university, there is no diminishing the correlation between campuses and good restaurants, bookstores, theaters and other amenities, driven by faculty, students and otherwise smart locals.

In this vein, I was personally sustained for more than three decades by NEBHE’s home in Boston. Despite its difficult racial past (which NEBHE and NEJHE have attempted to address), the Hub, and next-door Cambridge, comprise Exhibit A in such college-influenced communities. Indeed, our street in Downtown Crossing has offered a lesson in the region’s changing economy, being transformed from a strip of small nonprofits that wanted to be close to Beacon Hill, to dollar stores, to, most recently, chic restaurants and bars. The foot traffic, meanwhile, has become much more collegiate as Emerson College and Suffolk University have expanded downtown.

I noted in my letter to colleagues that I strongly believe that the regional journal is a key strength of NEBHE that should continue to be appreciated and bolstered.

For years, we characterized Connection and NEJHE as America’s only regional journal on higher education and its impact on the economy and quality of life. In addition, the topics we’ve covered are just too important to cast our gaze elsewhere. New England’s challenging demography—where some states now see more deaths than births—means there are fewer of us to nourish a workforce and exercise clout in Congress. This all makes our historic strength in attracting foreign students and immigrants to build our communities and industries all the more important. Growing chasms in income and wealth between chief executives and employees, meanwhile, agitate antidemocratic and racist forces. While too many critics diss snowflakes, dangerous trauma grows among students and staff. And a pandemic (that is not over) exposed our fault lines, but also showed the promise of joining together behind scientific breakthroughs … and behind one another.

NEBHE President Michael Thomas and I agreed that the weeks leading up to my retirement will provide opportunities to celebrate the journal’s four decades of contributions to the region—as well as to think about its future and the ways NEBHE can best inform and engage stakeholders going forward.

But these are tough times for independent-minded journalism—especially in the quasi-free press world of association journalism, where the goal is to be objective, but for a cause (and ours is generally a good one). NEBHE has launched a job search for a director of communications and marketing. To be sure, my functions at NEBHE also included PR and media relations and style maven (editorial style that is), and those too are key tasks that NEBHE must continue to fulfill. (Full disclosure, I always urged NEJHE authors to make their pieces “issue-oriented” and “avoid marketing.” The goal for the journal was to be thoughtful and candid.)

Just keep it real.

Here’s to the future of NEBHE and NEJHE.

John O. Harney is the executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Editor’s note: New England Diary’s editor, Robert Whitcomb, is a former member of the Advisory Board of The New England Journal of Higher Education.