Gorgeous globes

Work by Josh Simpson in his show “Josh Simpson: 50 Years of Glass,’’ at Salmon Falls Gallery, Shelburne Falls, Mass., through Dec. 31.

— Photo courtesy Salmon Falls Gallery.

The gallery says:

“In this exhibit, Josh Simpson looks back on his half-century of work in glass, displaying pieces that cover the breadth of what he can create. Notably, large, mesmerizing glass globes catch the eye. Also displayed are photos and video that show his process and technique. For more information, please visit here.’’

The famous Bridge of Flowers, along an old trolley bridge over the Deerfield River in Shelburne Falls.

‘Bare November days’

— Photo by E.mil.mil

My sorrow, when she’s here with me,

Thinks these dark days of autumn rain

Are beautiful as days can be;

She loves the bare, the withered tree;

She walks the sodden pasture lane.

Her pleasure will not let me stay.

She talks and I am fain to list:

She’s glad the birds are gone away,

She’s glad her simple worsted grey

Is silver now with clinging mist.

The desolate, deserted trees,

The faded earth, the heavy sky,

The beauties she so truly sees,

She thinks I have no eye for these,

And vexes me for reason why.

Not yesterday I learned to know

The love of bare November days

Before the coming of the snow,

But it were vain to tell her so,

And they are better for her praise.

“My November Guest,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

‘Humanity’s shared myths’

“Child of the Pure Unclouded Mind” (watercolor and oil on Arches paper (detail)), by Valerie Hird, at Burlington (Vt.) City Arts through Jan. 28.

The gallery says:

“Vermont-based and nationally acclaimed artist Valerie Hird explores the connections between cultures and their environment as a meditation on the ambiguities of our contemporary world. In her first solo exhibition at the BCA Center, Hird presents a provocative visual exploration of humanity’s shared myths. The artist envisions a fantastical garden where untamed and uncivilized nature becomes a metaphor for the pressures weighing on societal systems.

“Through a diverse vocabulary of colorful patterns and iconic symbols gathered and reimagined, Hird explores personal and collective identity – weaving together social, cultural, and political themes in a range of media. In this selection of new and recent work, Hird moves forward and backward across time and memory as she reflects on the illusion, disruption, and disarray within contemporary society. ‘The Garden of Absolute Truths’’ features large-scale paintings, animated video, and three-dimensional sculpture commissioned specifically for the exhibition.’’’

— All works courtesy of the Artist and Nohra Haime Gallery, New York

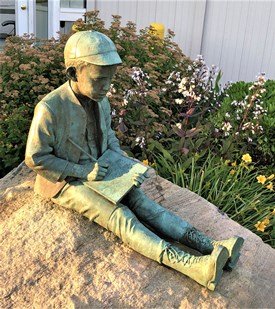

David Warsh: Tim Ryan says time to ‘Leave the age of stupidity behind us’

“An Allegory of Folly” (early 16th century), by Quentin Matsys

— EC Publications

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was the one ostensible mistake I made in what I wrote about the run-up to what did in fact turn out to be a nobody-knows-anything election.

To my mind, the most interesting contest in the country is the Senate election involving 10-term Congressman Tim Ryan and Hillbilly Elegy author J. D. Vance, a lawyer and venture capitalist. That’s because, if Ryan soundly defeats Vance, he’s got a good shot at becoming the Democratic presidential nominee in 2024.

Even now I don’t think that I was altogether wrong.

Thanks to the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal, we know why Ryan lost. Vance, who was on the ballot because Donald Trump endorsed him, trailed Ryan by significant margins until mid-summer. That was when Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell invested more than $32 million in the Ohio Senate race, via a super-PAC he controlled, 77 percent of all Republican campaign media spending in the Ohio election after mid-August. Most of it was negative “voter education,” enough to tip the balance against “taxing-Tim” for having voted for various Biden measures. The power of money in American elections may be a scandal, but by now it has been well-established by the Supreme Court as a fact of life.

It seems nearly certain to me that the next president will be someone born in the ‘70’s, not the ‘40’s. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat was probably correct when he wrote last week that Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is likely to be the Republican nominee. DeSantis, 44, was born in 1978.

Douthat may have been wrong, however, in thinking that DeSantis’s “sweeping success” in his re-election campaign validated the theory that “normal” doesn’t have to mean “squishy.” The tough-guy approach worked well in Florida. DeSantis was “an avatar of cultural conservatism, a warrior against the liberal media and Dr. Anthony Fauci, a politician ready to pick a fight with Disney if that’s what the circumstances require.”

But a better-mannered Donald Trump may not be what the majority of voters will be looking for in the next election. Tim Ryan, 49, was born in 1973. If you have time, and want a lift, watch Ryan’s 15-minute concession speech to get a feel for the man. Pay special attention to the six-minute mark, where Ryan speaks to the audience beyond the room he is in.

The words in that middle portion of that speech strike a powerful chord: “This country, we have too much hate, too much anger, there is way too much fear, way too much division. We need more love, more compassion, more concern for each other. These are important things. We need forgiveness, we need grace, we need reconciliation. We do have to leave the age of stupidity behind us.”

There are many question to be answered. First among them: are Ryan and his family willing to undertake a two-year front porch campaign? If so, a 10-term former congressman has a reasonable chance to win both the Democratic Party’s nomination, and the 2024 election itself.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

What they gave us

Naval Submarine Base New London is the primary U.S. Navy East Coast submarine base. It’s directly across the Thames River from its namesake city of New London. All U.S. subs are nuclear-powered.

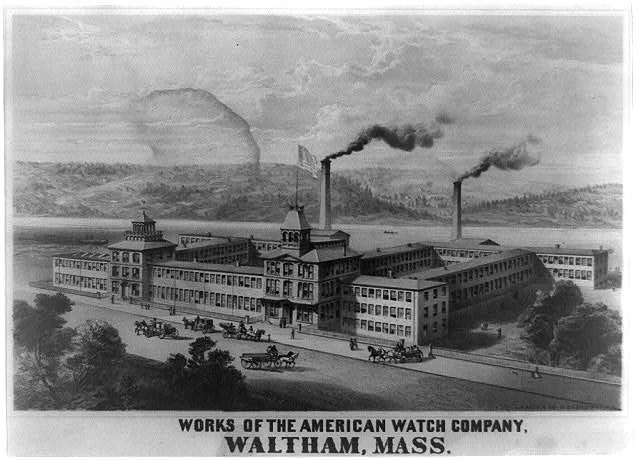

“New Englanders gave us codfish and quahogs and atomic submarines. They gave us the America’s Cup races and Waltham Watches, town meetings and mill towns, village greens and fall colors.’’

— Ted Smart and David Gibbon, in New England: A Picture Book to Remember Her By

The Waltham Watch Company made about 40 million watches, clocks, speedometers, compasses, time-delay fuses and other precision instruments between 1850 and 1957. The company's 19th-Century manufacturing facilities, in Waltham, Mass., have been preserved as the American Waltham Watch Company Historic District.

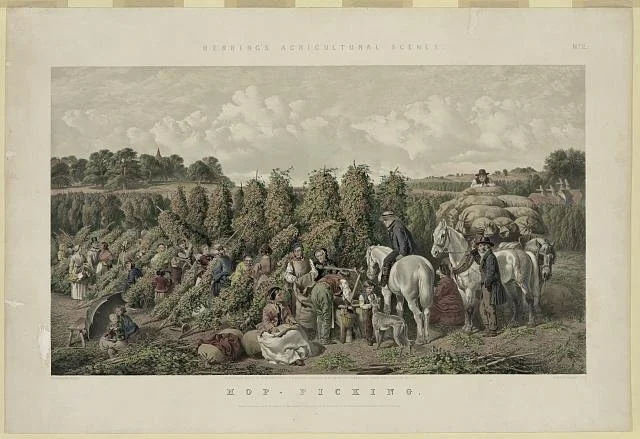

Even before germ theory

“Believing it to be the root of all human ills, our {New England} forefathers avoided drinking water whenever possible…. {In} the early days, family brewing was as important as family baking… and every housewife had her favorite recipes.’’

— Ella Shannon Bowles and Dorothy S. Towle, in Secrets of New England Cooking (1947)

Sarah Anderson: Voters made an end-run around out-of-touch politicians in mid-terms

Via OtherWords.org

This fall, in the lead-up to the mid-term elections, a group of Catholic nuns, Protestant ministers, and other faith leaders caravanned around South Dakota on what they called a “Love Your Neighbor Tour.”

They stopped in grocery stores, diners, senior centers, libraries and other community gathering spots to engage people in conversation about health insurance. They heard story after story of family members, friends, and neighbors who are having a hard time affording quality health care.

The goal of this tour: to build support for a ballot initiative to help more South Dakotans get the care they need.

Through such initiatives, citizens can make end runs around elected officials who’ve become disconnected from their constituents.

In this year’s election, voters in more than 30 states engaged in this form of direct democracy. These voters enshrined abortion rights in states like Michigan, funded universal pre-K and child care in New Mexico and cracked down on medical debt in Arizona.

In South Dakota, the “Love Your Neighbor” campaign won big. By a margin of 56 to 44, voters approved a proposal to force their state government to expand Medicaid eligibility, a move that will help an estimated 42,500 working class people get care.

These people earn too much to qualify for the state’s existing Medicaid program but too little to access private insurance through the Affordable Care Act. Since 2010, the federal government has covered 90 percent of the costs when states expand Medicaid, but political leaders in South Dakota and 11 other states have refused to do so.

This is not the first time that South Dakotans have used effective people-to-people organizing and ballot initiative strategies for the good of their neighbors.

Back in 2016, a bipartisan coalition with strong faith community support pulled off an incredible victory against financial predators, winning 76 percent support for a ballot measure to impose a 36 percent interest rate cap on payday loans. Previously, those rates had averaged around 600 percent in South Dakota, trapping many low-income families in downward spirals of debt.

In this mid-term election season, Nebraska offers another inspiring example of citizen action to bypass out-of-touch politicians.

For 13 years now, Republicans in Congress have blocked efforts to raise the federal minimum wage, letting it stay stuck at $7.25 since 2009. Nebraska’s entire Congressional delegation — all Republicans — have consistently opposed minimum wage hikes. Rep. Adrian Smith, for instance, recently attacked President Biden’s $15 federal minimum proposal as “economically harmful.”

Nebraskans view the matter differently.

Voters there approved a state minimum wage hike to the same level that Biden has proposed — $15 an hour — by 2026. The measure, which sailed through with 58 percent support, will mean bigger paychecks for about 150,000 Nebraskans.

Ballot measures like these can send a healthy wake-up call to political leaders who aren’t listening to their constituents. But certain special interests, especially ones with deep pockets and driven by narrow profit motives, don’t necessarily want ordinary Americans to be heard.

State legislatures around the country have seen a flurry of bills aimed at restricting or eliminating the ballot measure process. According to the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center, the number of such bills rose 500 percent between 2017 and 2021. Dozens more were introduced in 2022, including efforts to raise the threshold to pass a ballot measure beyond a simple majority vote.

The goal of these restrictions? To undermine the will of the people.

At a time when more and more Americans are worried about the future of our democracy, we should be applauding the advocates in South Dakota, Nebraska, and elsewhere who are engaging their fellow citizens in political decisions that affect their lives.

We need more democracy. Not less.

Sarah Anderson directs the Global Economy Project and co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies.

‘When home is hard to find’

“What I Have Found (detail)” (family ephemera), by Krystal Brown, in her show “Calling Home: Family Archives’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Nov. 27.

The gallery says:

“Krystle Brown compiles many layers of their late mother’s life growing up in Boston’s Dorchester, Mattapan, and Roslindale sections. Using family ephemera, photography and sound installation, Brown traces the many homes where their mother grew up and the people woven throughout her life. Part genealogy, part narrative, {the show} delves into the exploding economic inequality that threatens to unmoor social fabrics. By examining generational upheaval through displacement, Brown calls to attention the sanctity of the home, when home is hard to hold.’’

A portion of Roslindale Square on Belgrade Avenue, across the street from the Roslindale Village MBTA commuter rail stop.

— Photo by RHKindred

Boston as seen from the ESA Sentinel-2 satellite.

— Copernicus Sentinel-2, ESA

New Englander of the Year awards

The New England flag.

Hit this link to see The New England Council’s 2022 celebration, including recipients of its “New Englander of the Year” award.

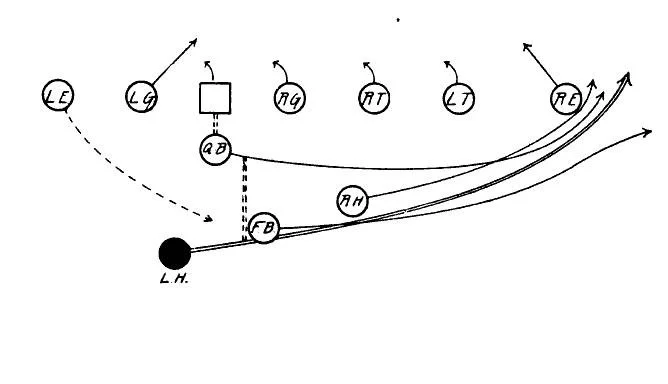

Chris Powell: Will real party competition ever return to Connecticut?

Blue places went Democratic in varying degrees, red ones Republican in Connecticut’s gubernatorial race.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

With the Democratic sweep in the Nov. 8 election, Connecticut remains pretty much a one-party state, which promises excess and even corruption more than good government. Changing the situation requires trying to understand what contributed to the election results.

Of course the controversies over former President Donald Trump and abortion were especially big advantages for Connecticut Democrats. Even the most pro-choice Republicans, such as gubernatorial nominee Bob Stefanowski, couldn't get past the abortion issue as his adversaries misrepresented his position.

Indeed, Stefanowski's campaign this year was far better than his campaign four years ago, which didn't go much beyond an unrealistic ambition to repeal the state income tax. This year Stefanowski addressed many issues specifically, drawing clear distinctions with Gov. Ned Lamont. But this time Stefanowski lost by more than three times as many votes as last time. The tide was against him and this time he was running against an incumbent.

The governor shamelessly exploited the advantages of incumbency, distributing during his campaign more state government financial patronage than any Connecticut governor in modern times had done. With $6 billion in state surplus funds, courtesy of "emergency" federal aid, the governor could camouflage state government's shaky finances and deflect concerns about higher taxes ahead, as with the return of the state gas tax in a few days.

The governor and Stefanowski both financed their own campaigns, but the governor, with huge inherited wealth, appears to have spent at least twice as much as his Republican challenger. Unlike the governor, Stefanowski had to work for the money he spent on his campaign.

With the exception of the nominee for U.S. representative in the 5th District, George Logan, the Republican underticket was weak, which may have been inevitable, since the minority party doesn't have much of a bench.

Leora Levy's challenge to U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal was an embarrassment, as she won the Republican primary as a Trump devotee who would outlaw abortion only to try to shed both poses in the general election campaign.

Polls suggested that Blumenthal, having been in elective office for almost 40 years, was growing tiresome and vulnerable, and his age showed during his debate with Levy. But he would not be beaten by an imposter.

xxx

The scope of the Republican failure in Connecticut may be best illustrated by the party's defeat in rich and traditionally Republican towns like Weston and in Fairfield County generally. Especially there Republicans should be asking themselves what future they have with Trump.

Indeed, if the party's failure to meet election expectations nationally this week is tied to Trump and the candidates he induced the party to nominate, and thus prompts Republicans to start jettisoning him as a gross liability, it may be a blessing in disguise.

xxx

Governor Lamont and the renewed Democratic majority in the General Assembly have won a great mandate that will feed desires for more government programs that only employ more Democrats, erode the private sector, and make more people dependent on government.

Republican leaders sometimes like to talk about the need to rebuild their party in the cities, which produce Connecticut's huge Democratic pluralities. But as government programs proliferate, the cities grow even more dependent on government and less open to political competition. Connecticut Democrats are proficient at merging government and party. Republicans are proficient at being quiet about it in the hope that the government employee unions won't campaign against them as much. Government's growth may already have locked Connecticut into being a one-party state.

xxx

But mandate elections can undermine themselves by fostering arrogance, and Governor Lamont may be hard pressed to resist the arrogance that will suffuse his party's legislative majorities despite the economic recession that has already begun.

In any case, if political competition in Connecticut is to be restored, it will have to begin with the Republicans who remain in the legislature. They will need to have something important to say and the courage to say it.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester. Connecticut. (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

Storyline of the left behind

“Aerie”, by Natick Mass., artist Roberta McGee Tuck, at the current group show “Shared Earth Habitat,’’ at Atlantic Wharf Gallery, Boston.

She says on her Web site:

“I am a fiber sculptor and a collector of lost objects. My work is inspired by the bits and fragments of land and sea debris that I gathers. Every object that I pick up has energy like an emotional artifact, containing a relation to an action, a person or an intriguing unknown. The depth and textures that are built up through sculptural experiments, become a layered narrative. On the surface, the objects within may only be unwanted debris, but the sculptural outcome that is composed is a multilayered storyline of what was left behind.’’

Natick Center. The Boston suburb has a very active arts community.

Photo by Rames1651

Physical reminders

Boston’s Old South Church, a United Church of Christ (Congregational) congregation organized in 1669

— Photo by GearedBull

“I mean to say that Boston is what she is today because the past is physically as well as traditionally a part of her modern life.”

David McCord (1897-1997), American poet and college fundraiser

Sermons behind the door

“That long fall,

when the voices stopped

in the tweed mouth

of his radio, and sermons

stood behind the door

of his study in files

no one would ever again inspect….’’

— “The Minister’s Death,’’ by Wesley McNair (born 1941), American poet, writer, editor and professor. He lives in Mercer, Maine.

The Mercer Union Meetinghouse, a historic church in the center of town, which is in the interior of The Pine Tree State.

‘A few incisive mornings’

— Photo by Peter.shaman

Besides the autumn poets sing,

A few prosaic days

A little this side of the snow

And that side of the haze.

A few incisive mornings,

A few ascetic eyes, —

Gone Mr. Bryant's golden-rod,

And Mr. Thomson's sheaves.

Still is the bustle in the brook,

Sealed are the spicy valves;

Mesmeric fingers softly touch

The eyes of many elves.

Perhaps a squirrel may remain,

My sentiments to share.

Grant me, O Lord, a sunny mind,

Thy windy will to bear!

—"November,’’ by Emily Dickinson (1830-1886)

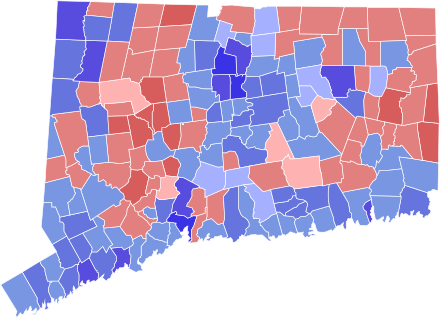

Stock up now!

The Providence Art Club’s famous “Little Pictures Show” is underway, its 118th. It runs through Dec. 23.

The highly anticipated yearly exhibition will feature more than 600 works of art from the club’s own members and staff, all priced at $350 and under. This is the time to find the newest additions to your local-art collection, pick up some holiday gifts or just browse for inspiration. With a rotating inventory, works purchased from this exhibition are strictly "pay and take away" on the day of purchase.

Small-town presidential politics

Cohasset Town Common, with Congregational church in the center background and the Unitarian church partly obscured by trees at left.

—Photo by Wwoods

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I rather fuzzily remember a flag-filled, informal motorcade in Cohasset, Mass., in 1956 for “Eisenhower for President’’. It was a fresh late-October day, with a northwest wind pulling the remaining red and orange leaves off the maples and the muted yellow ones off the hour-glass-shaped elms, of which we still had many, although Dutch elm disease was rapidly killing them off. Kids and their young parents applauded alongside the road.

We proceeded in our station wagon over a little bridge near the harbor and headed toward the classic town common (you can see it in The Witches of Eastwick), with the little pond with a fountain on a rock island in the middle of it. At the common, I recall, a generally genteel GOP campaign rally took place.

On two sides of the common were the two very white (in two senses of the word) Unitarian and Congregational churches. Nearby, on top of a granite outcropping, presided the neo-Gothic St. Stephen’s Church, a monument of the WASP upper-middle and upper class in the rather WASPY town. The local clan who owned much of Dow Jones & Co. had financed much of its building. See picture below of St. Stephen’s aristocratically looming over Cohasset’s downtown, next to the common.

The old line about the Episcopalians was “the Republican Party at prayer.’’ No more.

The town’s Catholic church, St. Anthony, was a few blocks away, in that still majority Protestant town. Its parishioners were generally of Irish, Italian and Portuguese background. We Protestants felt sorry for the Catholic kids because they had to go to catechism and confession (gulp!) and couldn’t eat meat on Fridays. The last rule, however, provided very good business for the local fishing fleet.

The more liberal and, for that time, “Bohemian,’’ folks attended the Unitarian Church – for which the joke motto was “the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man and the neighborhood of Boston.’’ The Unitarians removed as much as they could assertions about the divinity of Jesus from their hymns and liturgies. As the years passed, even references to God diminished. General, diffuse celebrations of the glories of nature and plugs for the Civil Rights Movement replaced them. The minister had the lovely name of the Rev. Roscoe Trueblood.

The Congregational (aka “Congo”) church in Cohasset was only vaguely Trinitarian. The Congos were more or less the direct descendants of the Puritans, the Unitarians less directly so.

There also was, and still is, a Hindu temple in town!

Back to the campaign motorcade. Some kids sang “Whistle while you work, Stevenson is a jerk,’’ of course a play on the song “Whistle While You Work,’’ from the Disney movie Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which all the children had seen.

It already seemed to me that politics was harsh.

Is it politically incorrect now to refer to “dwarfs’’?

The town and most of the rest of America went heavily for Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) over a former Democratic governor of Illinois, Adlai E. Stevenson (1900-1965). But the Republican Party was a very different creature from its current version, and Ike was a good, middle-of-the road president, supporting incremental improvements in federal domestic programs and warding off war. Both Eisenhower and Stevenson were notably dignified.

You can understand why a few years later, soon before his death, a very tired Stevenson, then U.S. ambassador to the U.N., would say that “All I really wanted was to sit in the shade with a glass of wine and watch the dancers.” I’m pretty sure that many of us, tired of the increasing toxicity and tumult of public life, would sometimes want to declare a separate peace and maybe flee, with no forwarding address, and certainly no social media, to some remote, Arcadian place. One thinks of the phrase “a separate peace’’ in Hemingway’s World War I novel A Farewell to Arms and John Knowles’s boarding-school novel, set in World War II, A Separate Peace.

In the Cohasset air was the aroma from piles of raked up (not blown!) leaves being burned – an activity now banned, mostly for public health reasons. Many of us of a certain age still miss that sweet smell, now replaced in too many neighborhoods by the aroma of gasoline from shrieking leaf blowers. Before their parents burned the leaves, small children loved to burrow into big piles of them.

Ah, youth! I remember with a pang the town’s scenic shores and the material comfort available to so many of its residents, along with dark scenes out of a Eugene O’Neill play.

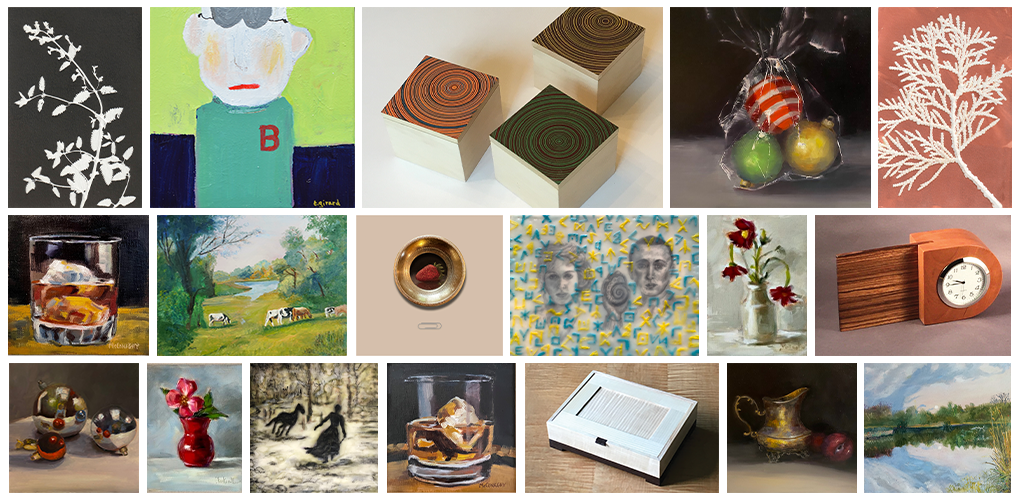

Buck up before signing up

Statue of Nobel Prize-winning playwright Eugene O'Neil (1888-1953) as a boy, overlooking the harbor of New London, Conn., where his family had a summer place and where some of his plays were based. As a young adult, he spent several years working in the merchant marine.

“The sea hates a coward.’’

—From the O’Neill play Mourning Becomes Electra

‘Mystery of life and death’

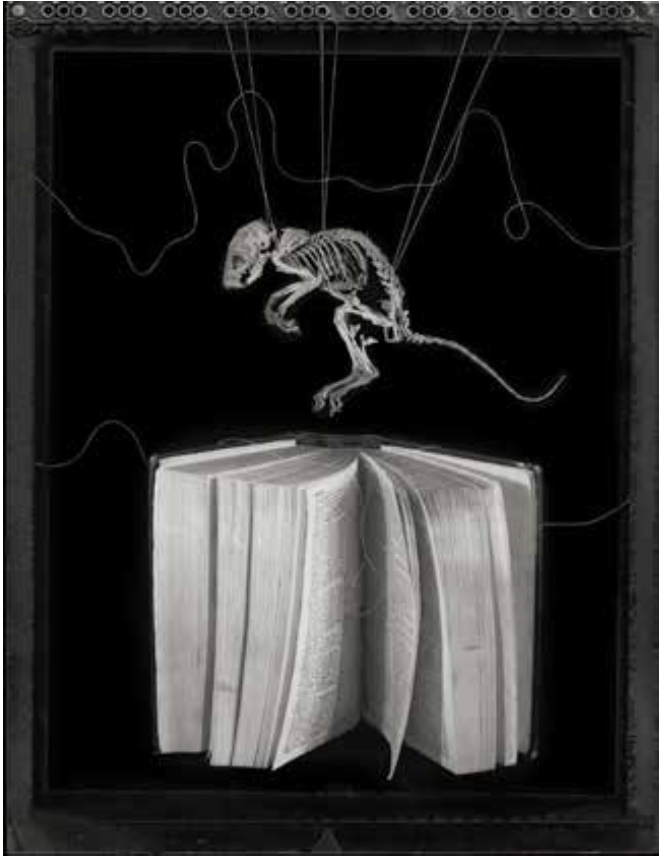

“Squirrel” (Iris print), by Vaughn Sills, a photographer based in Cambridge, Mass., and Prince Edward Island, at Anna Maria College, Paxton, Mass.

She says in her artist statement:

“I have chosen objects from nature one by one, found them, dug them, preserved them – a squirrel’s skeleton, poplar saplings that sprout from one long root, broken egg shells lying on the forest floor. I have taken them, or been given them, from the land on Prince Edward Island where my grandparents visited each summer, where I now have a cottage. I chose these things because of their extraordinary beauty – and because they seem to hold the mystery of life and death.’’”

Church in center of Paxton, Mass.

Stephen J. Nelson: Painful lessons in college leadership: Dartmouth College and the University of Florida

Nebraska Sen. Ben Sasse, soon to be president of the University of Florida, speaking at the 2015 Conservative Political Action Conference, a right-wing Republican event.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

In April 1981, David McLaughlin was named the 14th president of Dartmouth College. Though separated by four decades, there are striking similarities between Dartmouth’s appointment of McLaughlin and the University of Florida’s selection last week of its next president, Ben Sasse. If the past is prologue, Sasse and Florida are in for a rough ride.

McLaughlin was an alumnus of Dartmouth, both as an undergraduate and subsequently with an MBA from the Tuck School. While not from the Senatorial arena of Sasse, McLaughlin was a highly political animal. Dartmouth’s choice of him as president came at a moment for the college when disaffected conservative alumni were outraged about racial diversity and the opening of their male bastion to women. McLaughlin’s conservative politics and his purported fiscal belt-tightening reputation and presumed budgetary savvy as a corporate CEO at Champion Paper and Toro Corporation were thought by supporters to be great assets.

The conservative student newspaper, the Dartmouth Review, was about a year old. Conservative alumni, led by monied outside supporters, were opening their wallets and clamoring for more of the contentious voice of the Review. McLaughlin was expected to appease those forces. He promised reinstating ROTC, which had sat dormant for over a decade dating to when the faculty, in the heat of the Vietnam War, cut Dartmouth’s academic ties to the program. Conservative alumni and students cheered his arrival. McLaughlin was to be the fixer for conservative complaints about a new progressive Dartmouth—minorities, women and other changes—that they could not stand.

Sasse carries into his presidential tenure similar conservative baggage. His supporters have grand hopes that he will use the cudgels for which he is famous in the world of politics—decrying gay marriage, advocating overthrow of the Affordable Care Act, and being against abortion—to instill his social brand and edge into the culture of the university. He claims that will not be the case. But given his undeniable high-profile public positions on gay and lesbian issues and rights, abortion, healthcare, affirmative action and the MAGA agenda, the idea that Sasse will change his stripes and that his conservative political bent will now somehow disappear strains credulity and credibility.

As part of his welcome to the campus, the University of Florida faculty have already voted no confidence in the board’s selection process, a tantamount rejection of how and why Sasse was appointed in the first place. Again, if the Dartmouth experience with McLaughlin is any gauge, this vote is only the first salvo in what will be a continuing debate about Sasse as a university president.

From the outset of McLaughlin’s appointment, the Dartmouth faculty, like their Florida counterparts, voiced immense skepticism about the board’s process that resulted in his selection. In the introductory open public faculty meeting that April 1981—I was in the room, then a student affairs administrator—McLaughlin was greeted by pointed criticism from Dartmouth professors. They questioned his capacity to lead in a college and academic culture that was the antithesis of his exclusive corporate sector autocratic and top-down experience. Several faculty members railed to his face about his glaring lack of academic credentials—an MBA, but no Ph.D.—about having no experience teaching and leading a college, bringing only business experience that would never translate to being Dartmouth’s voice in the presidential pulpit.

There was no vote of no confidence in the trustees at the time of their decision. That came four years later dressed in the garb of the unprecedented impaneling of a committee to review McLaughlin’s performance as president. But the Dartmouth faculty restiveness and fear was unmistakable. Their misgivings and judgment that day were born out in a tumultuous, contentious and divisive presidential tenure marked by aggressive, vindicative grudge-based senior administrative turnover, duplicitous leadership, e.g., saying one thing to one group or individual and then the direct opposite to someone else, and a divide-and-conquer style that pitted campus constituencies against each.

For many observers, the Sasse and McLaughlin appointments are sadly only grasped as institutional overreach designed to satisfy certain constituents, rather than aspiring to the greater good of the entire university. McLaughlin lacked fundamental leadership abilities in a president of a college or university. As Sasse assumes the presidency of the University of Florida, there are eerie parallels to Dartmouth’s experience more than 40 years ago. This reality dictates that the Florida faculty must be robust in their scrutiny of how Sasse carries himself, the decisions and actions he takes and his leadership of their university community and its culture. Based on the experience of McLaughlin at Dartmouth, that means the Florida faculty must be vigilantly tuned in to what goes on in the who’s and why’s of senior leadership turnover and new appointments and to kneejerk tendencies to favor conservative causes and to support conservative over liberal professors, student groups and leaders. They must also be attentive to any fiscal and fundraising sleight-of-hand and abuse of the books to make the president look successful.

What is always essential in the leadership of America’s colleges and universities is the naming of presidents who possess critical capacities and commitments: moral grounding, the broad center of understanding and the intellectual gravitas essential in the quest to engage academic communities in the forthright pursuit of intellectual inquiry, freedom of ideas and discourse, and the common good.

Worthy and great college presidents are not accidents or the result of luck. Ill-fitted, ill-suited presidents can do great damage. Early glimmers of what is in the offing reveal what the path might be. Sasse, his faculty and all the constituencies of the University of Florida are on a precipice.

They should look at what happened at Dartmouth in the 1980s, when pressures for conservative, return to a bygone era leadership overwhelmed common sense calling for an academically, intellectually and balanced credible presidential appointment, one truly fit for the complexities and diverse voices in a university community. At Dartmouth, McLaughlin’s selection sorely damaged the esprit de corps of administrative staff, eroded \ the stature and public image of the college and caused a corrosive cynicism in the campus community about its culture. The realities of such presidencies should make all wary indeed.

Stephen J. Nelson is professor of educational leadership at Bridgewater State University and Senior Scholar with the Leadership Alliance at Brown University. He is the author of the recently released book, John G. Kemeny and Dartmouth College: The Man, the Times, and the College Presidency. His forthcoming book, Searching the Soul of the College and University in America: Religious and Democratic Covenants and Controversies, will be released in 2023. Nelson served on the student-affairs staff at Dartmouth College from 1978 to 1987.

Nimbys vs. more housing

Rockport’s inner harbor showing lobster fleet and Motif #1 (red building), one of the most painted buildings in America.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Just how hard it is to build more housing (except for mansions and McMansions) in New England can be seen in Rockport, Mass., the affluent town on the tip of Cape Ann. It’s both a Boston suburb and a summer-resort town, with many second homes.

There, a bunch of Nimbys seek to block a state plan to put multi-family housing near the town’s train station. The project is aimed at slowing soaring housing costs by increasing supply and getting more people out of their cars and into environmentally friendly public transit.

Rockport, with its famous ‘’quaint’’ harbor (“Motif #1, beloved by Sunday painters!), is a major tourist destination but the people who work in its restaurants, inns and bars increasingly can’t afford to live there. This has helped to cause severe labor problems in the local and heavily taxpaying hospitality sector – leading to shortened hours and outright closures.

This sort of opposition has cropped up in other rich towns, such as Newton. The Rockport project is driven by the new rules of the administration of outgoing Republican Gov. Charlie Baker aimed at increasing multi-family housing, especially for low-income people, in the 175 cities and towns served by the MBTA.

I hope that the commonwealth continues to enforce these rules. If not, Massachusetts, like the other New England states, will lose many more jobs to the South and West where more, and more affordable, housing is available. It’s a social and economic imperative for our region to build much more housing.

Swimmers’ delight: Babson Farm granite quarry, at Halibut Point State Park, in Rockport.