Jim Hightower: The asset strippers destroying local newspapers

Via OtherWords.org

Editor’s note: Gannett owns many New England newspapers, including The Providence Journal and The Worcester Telegram.

My newspaper died.

Well, technically it still appears. But it has no life, no news, and barely a pulse. It’s a mere semblance of a real paper, one of the hundreds of local journalism zombies staggering along in cities and towns that had long relied on them.

Each one has a bare number of subscribers keeping it going, mostly longtime readers like me clinging to a memory of what used to be and a flickering hope that, surely, the thing won’t get worse. Then it does.

Our papers are getting worse at a time we desperately need them to get better. Why? Because they are no longer mediums of journalism, civic purpose, or local identity.

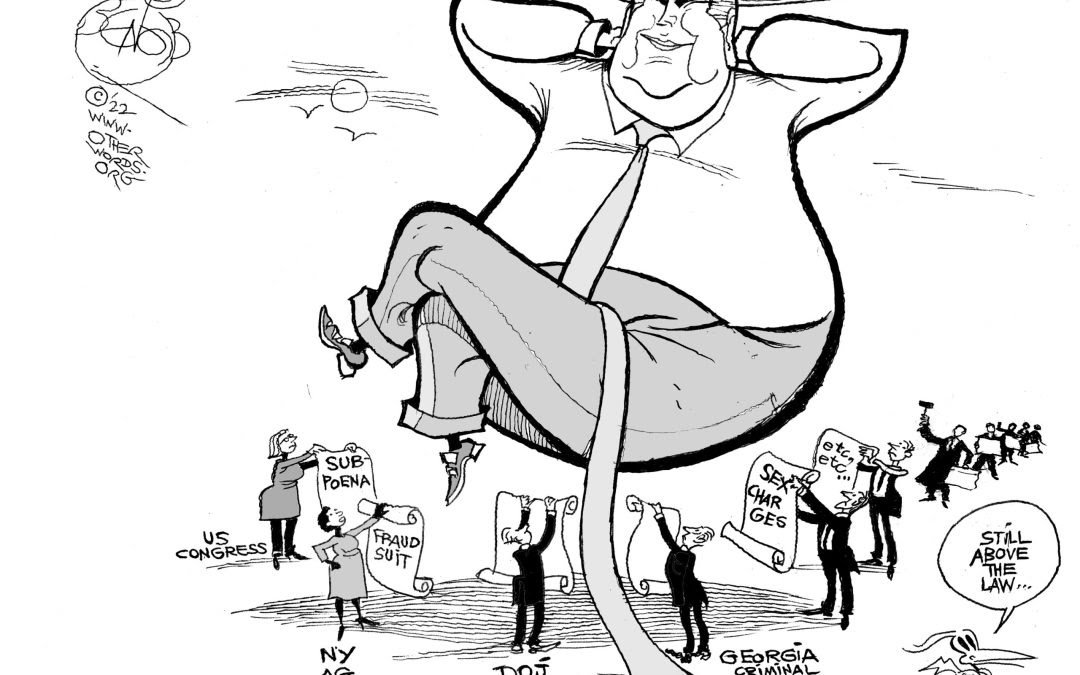

Rather, they’ve been reduced to little more than profit siphons, steadily piping local money to a handful of distant, high-finance syndicates that have bought out our hometown journals. My daily, the Austin American-Statesman, was swallowed up in 2019 by the nationwide Gannett chain, becoming one of more than 1,000 local papers that Gannett mass produces under its corporate banner, “the USA Today Network.”

But even that reference is a deception. The publication doesn’t confide to readers that it’s actually a product of SoftBank Group, a multibillion-dollar Japanese financial consortium that owns and controls Gannett.

SoftBank has no interest in Austin as a place, a community, or even as a newspaper market, nor does it care one whit about advancing the principles of journalism. It’s in the profit business, extracting maximum short-term payouts from the properties it owns.

This has rapidly become the standard business model for American newspapering. Today, more than half of all daily papers in America are in the grip of just 10 of these money syndicates. That’s why our “local” papers are dying.

It’s not a failure of journalism. It’s a plunder of journalism by absentee corporate owners.

Linda Gasparello: Letter from Bonny and eerie Edinburgh

A woman waiting for a bus on Princes Street in Edinburgh on a moonless October night.

— Photos by Linda Gasparello

I play a silly game of characterizing cities as things. Here’s how it goes: If London were a holiday, which one would it be? My answer -- no doubt influenced by Charles Dickens -- is Christmas. Paris is New Year’s, because I’ve spent a few memorable ones there, feasting, drinking bubbly and giving cheek kisses.

Halloween? New Orleans, with its haunted French Quarter houses, voodoo and vampire lore, is my pick. But Edinburgh can give The Big Easy a run for its money as I noted when my husband and I visited the Scottish earlier this month.

In fact, Edinburgh has just been named one of the top three creepiest cities in the United Kingdom by Skiddle, an events-discovery platform, based on the combined number of reported hauntings and Halloween-themed events. According to Skiddle, bookings of ghost tours are way up in London and Brighton, which take the top two places in its survey, and Edinburgh.

Greyfriars Kirkyard

A terror-tour favorite in Edinburgh, Greyfriars Kirkyard, a church cemetery established in the mid-16th Century, is a one-stop shop of horrors, replete with ghosts, ghouls and bodysnatching.

I would’ve thought that the British tourists would’ve been spooked enough by the economic ghosts of 1979 -- a stagnant economy, surging inflation and waves of industrial unrest, trounced by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s free-market policies in the following years.

A couple with Halloween-colored hair celebrating at The Deacon Brodie's Tavern in the Lawnmarket.

Prime Minister Liz Truss, who resigned amid the Tory turmoil, was no ghostbuster.

Yes! We Have No Newspapers

There is a newsagent on Princes Street, near the Apex Waterloo Place Hotel. Above the door hangs a sign for The Scotsman, the Edinburgh daily, flanked by two smaller signs for other city newspapers: The Evening News, and the Daily Record and Sunday Mail.

My husband and I stopped in to buy some newspapers, keen to read the coverage of the Scottish National Party Conference. But we found none there.

Yes, they had Fyffes bananas, and the shelves were stacked nearly to the ceiling with boxes of “sweet biscuits” and shortbread, especially the shiny red tartan boxes of Walkers Shortbread, advertised on the shelf as the “Walkers Pure Butter Luxury Shortbread Top Quality All Size Box 3.99 p.”

I walked up to the cashier, a young man of South Asian origin, and asked if he sold newspapers. He said he gave up selling them because he didn’t want to deal with the “all the paperwork and returns for a few pence on a sale.”

Anyway, he adamantly said, “Nobody ever needs to read newspapers. They have nothing in them, only opinions.”

Surely, I said, there’s a newsagent in the vicinity that sells newspapers. Somewhat grudgingly, he told me to go to the WHSmith shop in the train station.

I left the no-news newsagent and walked to the station. I bought 15 pounds (about $17) worth of newspapers at the WHSmith because I’m a big-spending nobody

Sir Jim, ‘The Bonnie Baker’

I read in The Herald that Walkers Shortbread’s profits had more than doubled to 62 million pounds (about $69.2 million) this year, boosted by strong demand in key markets.

In the late 1980s, when I was the editor of a global food-industry paper, I interviewed Jim Walker, head of the family-owned baking company, which was founded by Joseph Walker in 1898. In my story about Walkers, I dubbed him “The Bonnie Baker.” He is now Sir Jim, having received his knighthood in the late Queen’s Birthday Honors earlier this year.

Walker told The Herald that it had been “a very, very difficult couple of years” due to COVID and supply problems. “Butter has virtually doubled (in price), and the price of flour has gone up as well,” he said.

Butter was a problem for Walker in the late 1980s, but for quite a different reason.

In the U.S. cookies market, where Walkers wanted more penetration, it was a bad time for butter. Spurred by food activists, such as the Center for Science in the Public Interest, consumers were demanding that cookie makers eliminate highly saturated fats, from butter to palm oil, in their products.

On a visit to the company’s headquarters, in Abelour, in The Highlands, during that saturated fat-cutting time, I offered Walker this advice: Find a healthy butter substitute.

“No, we can’t,” he said firmly. “Butter is one of four shortbread ingredients.”

I offered him another pat of advice: Extend the brand’s product line with chocolate-chip shortbread.

This was probably already in the works, but I’d like to think that I was responsible for Walkers adding another ingredient -- and going on to become the largest British exporter of shortbread and cookies to the U.S. market.

Buchanan Fish Fight

The Buchanan clan has its first new chief in more than 340 years.

“The last Buchanan chief, John Buchanan, died in 1681 without a male heir. Identifying the new chief required decades of genealogical research conducted by renowned genealogist, the late Hugh Peskett,” according to History Scotland, a Scottish heritage Web site.

John Michael Ballie-Hamilton Buchanan was inaugurated Oct. 8 in a ceremony in Cambusmore, Callander, the modern seat of Clan Buchanan and the chief’s ancestral home. International representatives of the clan’s diaspora – from North America (count conservative commentator Patrick J. Buchanan) to New Zealand -- celebrated alongside the chiefs and other representatives of 10 ancient Scottish clans, History Scotland reported.

“Speaking before the inauguration, Lady Buchanan said they expected many neighboring clans to attend – despite, in some cases, a long history of rancor,” The Daily Telegraph’s Olivia Rudgard wrote.

“ ‘Spats’’ involving the Buchanan clan include a 15th Century feud with Clan MacLaren, apparently started at a fair when a Buchanan man slapped a member of the MacLaren clan with a salmon and knocked his hat off his head.

“It ended in a bloody skirmish which killed, among others, one of the sons of the MacLaren chief,” Rudgard wrote.

With apologies to Robert Burns, a Scot’s a Scot, for a’ that -- and Scotland is a bonny place to visit.

Linda Gasparello, based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C., is producer and co-host of White House Chronicle, on PBS

Llewellyn King: Utilities face more demand, less generation

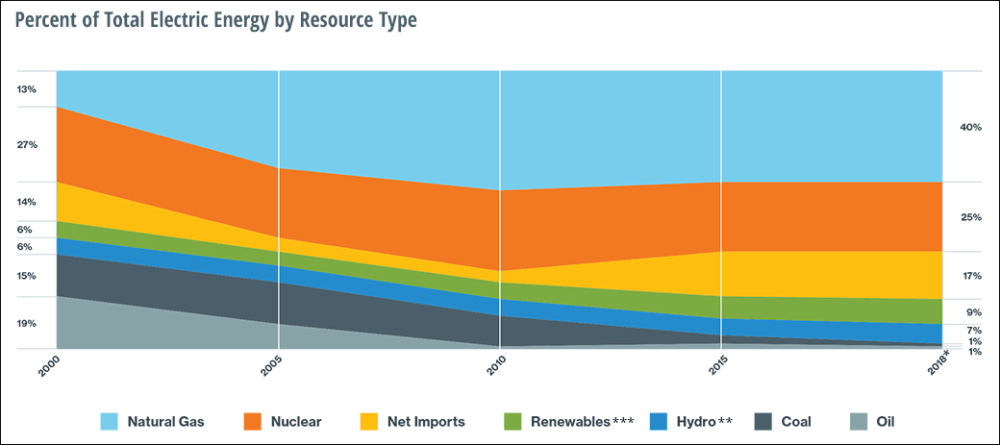

How New England's energy mix has changed since 2000 -- before the closure of the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant, on the coastline in Plymouth, Mass., which was shut in 2019.

— — Courtesy of ISO New England

The Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant, with the Manomet Hills behind.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

America’s electric utilities are facing revolutionary changes as big as any they have faced since Thomas Edison got the whole thing going in 1882.

Between now and 2050 – just 28 years -- practically everything must change: The goal is to reach net zero, the stage at which the utilities stop putting greenhouse gases, especially carbon dioxide, into the atmosphere.

But in that same timeframe, the demand for electricity is expected to at least double and, according to some surveys, to exceed doubling as electric vehicles replace fossil-fueled vehicles and as other industries, such as cement and steel manufacturing, along with general manufacturing, go electric.

Just eliminating fossil fuel alone is a tall order -- 22 percent of the current generating mix is coal, and 38 percent is natural gas. Half of the generation will, in theory, go offline while demand for electricity soars.

The industry is resolutely struggling with this dilemma while a few, sotto voce, wonder how it can be achieved.

True, there are some exciting technological options coming along: hydrogen, ocean currents, small modular nuclear reactors, so-called long-drawdown batteries, and carbon capture, storage and utilization. The question is whether any of these will be ready to be deployed on a scale that will make a difference by the target date of 2050.

There are other schemes -- still just schemes -- to use the new electrified transportation fleets as a giant national battery. The idea is that your electric vehicle will be charged at night, or at other times when there is an abundance of power, and that you will sell the power back to the utility for the evening peak, when we all fire up our homes and electricity demand zooms.

This is just an idea and no structure for this partnership between consumer and utility exists, nor is there any idea of how the customer will be compensated for helping the utility in its hours of need. It is hard to see how there will be enough money in the transaction to cause people to want to help the utility because besides the cost of charging their vehicles, the batteries will deteriorate faster.

The ongoing digitization of utilities means that they will be able to better manage their flows and to practice more of what is called distributed energy resources (DER), which can include such things as interrupting certain nonessential users by agreement.

David Naylor, president of Rayburn Electric Cooperative, bordering Dallas, says that DER will save him as much as 10 percent of Rayburn’s output, but not enough to take care of the escalating demand.

Like many utilities, Rayburn is bracing for the future, expecting to burn more natural gas and add solar as fast as possible. They are also upgrading their lines, called connectors, to carry more electricity.

The latter highlights another major challenge for utilities: transmission.

The West generates plenty of renewable power electricity during the day, some of which goes to waste because it is available when it isn’t needed in the region, but when it would be a boon in the East.

The simple solution is to build more long-distance transmission. Forget about it. To get the many state and local authorizations and to overcome the not-in-my-backyard crowd, most judge, wouldn’t be possible.

Instead, utilities are looking to buttress the grid and move power over a stronger grid. In fact, there isn’t one grid but three: Eastern, Western and the anomalous Texas grid, ERCOT, which is confined to that state and, by design, poorly connected to the other two, although that may change.

Advocates of this strengthening of the grid abound. The federal government is on board with major funding. Shorter new lines between strong and weak spots would go a long way to making the movement of electricity across the nation easier. They would also move the nation nearer to a truly national grid. But even building short electric connections of a few hundred miles is a fraught business.

The task of the utilities -- there are just over 3,000 of them, mostly small -- is going to be to change totally while retooling without shutting off the power. The car companies are totally changing, too. But they can shut down to retool. Not so the utilities. Theirs must be revolution without disruption: the light that doesn’t fail.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Julia Child: ‘Never apologize’

Julia Child in her kitchen in Cambridge in 1978, in a publicity shot.

“The only time to eat diet food is while you’re waiting for the steak to cook.’’

“No matter what happens in the kitchen, never apologize.”

“People who love to eat are always the best people”

“Always remember: If you’re alone in the kitchen and you drop the lamb, you can always just pick it up. Who’s going to know?”

“You learn to cook so you don’t have to be a slave to recipes.”

— Famous lines by Julia Child (1912-2004), TV food-show star (via WGBH, in Boston, where she was the star of The French Chef), author, teacher, semi-comedian and in World War II a quasi-spy with the OSS. She lived in Cambridge, Mass., for 40 years and was a big character in many ways.

‘Every leaf, rock and tree’

“Protector” (detail), (alabaster, wonderstone, pine needles), by Robin MacDonald-Foley, in her show “The Forest Voice,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Nov. 4-27.

She tells the gallery:

"Inspired by ancestral history, ‘The Forest Voice’ reflects my journey, communicated through sculptural figures, bowl-like vessels, and woodland photographs. Every leaf, rock and tree, becomes part of the dialogue. Exploring my family’s shared places, those I know and some I’ve yet to experience, I’m recreating events through the mystery and folklore of the forest. To those who sheltered and foraged, with hope and fortitude, my stories are offerings of love, light and guidance. May you always find your way."

Even fairly small towns in Greater Boston had streetcars back in 1912, when this photo was taken.

Proud of their maze; more knowledge for the knowledgeable?

Already a maze in 1775.

Near Boston City Hall after the Blizzard of ‘78,

“Boston

”Rich with historical facts

Where the city is a maze

And the snow get stacked.

”Yeah, we got hit

And we felt the impact

But we respond first

And yes, we bounce back.’’

— From the 2013 song “Boston Strong,” by Mr. Lif (born 1977), written in the wake of the Boston Marathon bombing, which happened on April 15, 2013.

xxx

“The Boston people were willing to learn, but only if one recognized how much they knew already.”

— Van Wyck Brooks (1886-1963), American literary critic, historian and biographer

The permanent doesn’t exist

“Ephemerality” (mixed media), by Dawn Surratt, in the group show “The Morphing Medium,’’ at the Maine Museum of Photographic Arts, Portland, through Dec. 3

—Photo courtesy Maine Museum of Photographic Arts.

The museum says:

“This expansive show contains the work of 18 artists who work in the medium of photography. But this is anything but your standard photography show. Artists use the full breadth of what the medium has to offer, pushing the boundaries of technique, material and composition.’’

Gun recovered from the USS Maine on Munjoy Hill, in Portland. The explosion that sank the ship in Havana Harbor on Feb. 15, 1898 was a catalyst for the United States to launch its war against Spain. However, no one has proven what caused the explosion.

— Photo by Ryssby

Felice Duffy: Forward or backward with new Title IX regs?

— Photo by Sichow

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

NEW HAVEN, Conn.

On the 50th anniversary of the enactment of Title IX, the U.S. Department of Education released proposed new regulations for Title IX policies. For the most part, these new regulations reverse regulatory changes made during the Trump administration.

The Biden administration insists the new regs will “restore crucial protections” that had been “weakened.” Commenters have their own opinion on the efficacy of the proposed regulations, with over 235,000 formal comments filed during the 60-day comment period.

So, do the proposed regulations represent a step forward or backward?

Overview of changes

The deceptively simple words in Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 have been augmented by numerous regulations and judicial interpretations over the decades. While the aim is to protect students from sex-based discrimination, many worry that the regulatory efforts to right or prevent wrongs go too far and infringe on the due process rights of those accused of Title IX violations.

During the Trump administration, the Office for Civil Rights spent nearly 18 months reviewing less than 125,000 public comments before issuing new final regulations that resulted in significant changes. With almost 90% more comments to review this time around, it will be interesting to see how long it takes the department to issue final rules about key issues they are considering, such as:

How colleges are required to investigate reports of sexual assault.

Whether colleges are required to hold live hearings before issuing decisions.

Protections for LGBTQIA+ students.

The definition of sexual harassment.

While some commenters object that the proposed rule changes go too far in one direction, others insist they do not go far enough.

Live hearings and cross-examination

One of the most significant controversies regarding the proposed regulations centers on the types of proceedings colleges must hold to hear Title IX complaints. The new regulations allow schools to hold separate private meetings with complainants and respondents instead of live hearings with the opportunity for cross-examinations. Supporters of the change assert that the disciplinary hearings required under current rules are too much like adversarial courtroom proceedings. Many say that allowing colleges to establish less formal, non-confrontational processes will save money and encourage victims to proceed without fear of repercussions.

However, other commenters expressed concerns that eliminating live hearings and allowing colleges to use the same body to investigate and judge the validity of complaints violates the due process rights of students accused of violations.

Burden of proof in sex discrimination and misconduct

Controversy continues about how much a complainant must prove to win a case alleging that they have been subjected to sexual discrimination, harassment or assault. The proposed rules would generally establish a “preponderance of evidence” standard in most but not all cases, so a student need only to prove that it was “more likely than not” that the discrimination occurred. The current rules provide a choice between the preponderance of evidence and clear and convincing evidence standards.

Critics of the change say the clear and convincing standard is necessary to protect the respondent’s rights, and they point out that it is still less than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard used in criminal cases.

Gender identity and sexual orientation

The proposed regulations expand the anti-discrimination protections of Title IX to include gender identity and sexual orientation when it comes to college programs or activities, except athletics. The department has delayed ruling on the highly controversial issues related to participation in sports programs.

Even without addressing athletics, the expansion of protections generated numerous forceful comments. Those in favor assert that the new rules will improve the safety and wellbeing of LGBTQIA+ students and resolve equality issues that are currently being addressed on a costly case-by-case basis in the courts. Opponents of the expansion allege that by requiring schools to allow participation in programs based on gender identity, the new regulations actually violate the Title IX mission of providing equal access to education benefits on the basis of sex. They also argue that the proposed changes exceed the department’s statutory authority and would chill free speech rights on campus. For example, the definition of sexual harassment will be expanded such that students could be investigated for not using certain pronouns or using incorrect pronouns that do not correctly reflect the gender with which a person identifies.

Are we moving forward or backward?

While the new regulations are not yet final, the final regs are expected to track closely with the proposed version. Whether you are a complainant or a respondent regarding any number of explicit proposed provisions in the regulations, each side would argue the provision is either moving toward a brighter future or repressive past—any provision that makes it more difficult to file a complaint (such as requiring a formal complaint under the current regs) makes it harder for complainants (repressive past) and easier for respondents (brighter future); and keeping the standard at the preponderance of evidence versus raising it to clear and convincing, is easier for complainants (repressive past) and more difficult for respondents (brighter future).

The one certainty is that when schools implement the new regulations, those who are unhappy with the results will turn to the courts for clarification and possible nullification. It will be interesting to see how the courts respond.

Felice Duffy is a Title IX lawyer with Duffy Law, based in New Haven, Conn., and a former federal prosecutor.

David Warsh: The arduous advance of economics as seen through Nobel prizes

The Nobel Prize in Economics committee took note about this famed film, which revolves around a local banking crisis in The Great Depression.

STOCKHOLM

Eight economists have received invitations to Stockholm in December, three of them living, five of them dead. Three will show up, to accept their Nobel Memorial Prizes in the Economic Sciences. The five Spirits summoned, all but one laureates themselves, are still teaching, though only as textbook legends. A sixth Specter, significant to the story, did not make the list. He died in 2018.

Ben Bernanke, an applied economist who gradually became a central banker, and theorists Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig, who remained university professors for forty years, were recognized last week for two particular papers about banking and financial crises they wrote in 1983

“Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance and Liquidity,” by Diamond and Dybvig, in the Journal of Political Economy; and “Nonmonetary effects of the financial crisis in the propagation of the Great Depression,” by Bernanke, in the American Economic Review, were the only the first statements of the problems on which they intended to work. Many other technical papers followed, at first by the authors themselves, then by members of growing community of fellow-researchers determined to extend the boundaries of the field.

Neither of those first two papers settled anything. Together, however, they announced research projects that constituted “discoveries,” in the language of the citation, which, in the course of time, and in combination with the insights of many others, “improved how society deals with financial crises” – a key condition of many Nobel Foundation economics prize.

How? By demonstrating to a new generation of researchers how to approach exploring the previously uncharted territory of “financial intermediation,’’ meaning the operations of the institutions that occupied the larges space between two well-established regions: Keynesian macroeconomics, and its preoccupation with business cycles; and “monetarism,” a somewhat old-time fascination with the history and theory of money and banking.

In other words, this year’s prize recognizing the financial macroeconomics that has begun to emerge like a new textbook chapter from the void is more rhetorically powerful than it seemed, at least in the course of the usual show-business ceremony with which the prize was announced Oct. 10.

A 72-page essay on the scientific background of the award spelled out the story for those with the curiosity and patience to read. It tells a story of how economics makes progress: one generation of economists feasts on the glory of another. That is, newcomers to the discipline supplant one source of excitement with another. In this case, the new excitement arrived just in time.

. xxx

From the very beginning of their modern science, in the 18th Century, the background citation asserts, economists were well aware of the existence and nature of banks, of course. David Hume and Adam Smith were well aware of how bankers took deposits and then extended much more credit than the cash reserve they kept in the till. Hume and Smith knew all about the panics that regularly occurred when all the depositors wanted their money back at the same time. (The long Nobel citation mentions the Frank Capra movie, It’s a Wonderful Life.) Smith reasoned that free competition among banks would solve the problem, as long as lenders were prudent and followed the “real bills” rule.

During the 19th Century, economists mostly left the discussion of banks to bankers (Henry Thornton) and journalists (Walter Bagehot) while they worked on the problems of supply and demand that they cared about most. What they called “general equilibrium theory” emerged. Only in 1888 did the pioneering mathematical economist and statistician Francis Ysidro Edgework construct the first model of fractional banking.

Fast forward to the years after World War II, when economists began to write much more in mathematics instead of natural language, the better to be clearer among themselves. The ramifications of competition gradually became clear by formally modeling it as though it were perfect. And the first major payoff of mathematical language was the discovery that, at least in some important ways, everyday competition definitely wasn’t perfect. A model of monopolistic competition had emerged in the 1930s, a little too early for the Nobel Committee to take note of it; the first economics prize wasn’t given until 1969. Meanwhile, banking, whatever it was, remained the business of bankers.

In the 1970s, a significant part of the excitement in mainstream economics had to do with something called the Modigliani-Miller theorem. The authors, Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller, had met in the 1950s as colleagues at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh. In 1958 they agreed to teach a course in corporate finance in the business school there. What emerged was what Peter Bernstein, in Capital Ideas, The Improbable Origins of Modern Wall Street (1992), called “the bombshell assertion.” This was the proposition that, thanks to the principle of arbitrage, the ratio of debt to equity in a firm’s capital structure didn’t matter; Under perfect competition, in the absence of frictions and asymmetries of all sorts, no matter how the firm was financed, the enterprise value of the firm would be the same.

Enter financier Michael Milken, who in the 1970s pioneered modern high-yield (“junk”) bonds. Soon the debt-based restructuring takeover boom of the 1980s was underway. Modigliani was recognized in 1985 by the Nobel Committee “for his pioneering studies of savings and financial markets.” Five years later, Miller shared the prize with two other pioneers in finance for, in his case, his collaboration with Modigliani on the article “The Cost of Capital, Corporate Finance and the Theory of Investment.”

It was amid this commotion that the situation arose in which Diamond and Dybvig took up their challenge. Many banks in the 1980s were large and ubiquitous around the world, and enormously profitable. But why did they exist at all? In 1980, the author of one survey of the literature on banking stated: “There exist a number of rival models and approaches which have not yet been forged together to form a coherent, unified and generally accepted theory of bank behavior.”

Diamond and Dybvig did just that, according to the citation, offering two critical insights in the process. There were “fundamental reasons why bank loans are a dominant source of financing in the economy” for one thing, and “for why banks are funded by short-term, demandable debt.” For another, that meant that “banks are inherently fragile and thus subject to runs.”

. xxx

Bernanke approached the problem of financial intermediation from a different direction – from curiosity about the mechanisms of business cycles characteristic of the Keynesian macroeconomics that he studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dale Jorgenson had been Bernanke’s adviser at Harvard College. Stanley Fischer supervised his dissertation, along with Rudiger Dornbusch and Robert Solow. He finished “Long-term commitments, dynamic optimization, and the business cycle” in 1979 and took a job at Stanford University.

As the Nobel citation puts it:

“The dominant explanation at the time for why the Great Depression was so deep and prolonged was due to Milton Friedman and his wife, Anna Schwartz (1963). They argued that the waves of banking crises in 1930–1933 substantially reduced the money supply and the money multiplier. The failure of the Fed to offset this decline in money supply in turn led to deflation and a contraction in economic activity.’’

Friedman had moved from Chicago to San Francisco, where he taught part-time at nearby Stanford. There was not much other than traditional money and banking in A Monetary History of the United States, by Friedman and Schwartz, The citation continues,

Bernanke (1983) proposed a new (and in his view complementary) explanation of why the financial crisis affected output. According to this view, the services that the financial intermediation sector provides, including “nontrivial market-making and information gathering,” are crucial for connecting lenders to borrowers. The bank failures of 1930–1933 hampered the financial sector’s ability to perform these services, resulting in an increase in the real costs of intermediation. Consequently, borrowers – particularly households, farmers and small businesses – found credit to be expensive or unavailable, which had a prolonged negative effect on aggregate demand. Bernanke combines examination of historical sources, statistical analysis, and (at the time) recent theoretical insights to build this argument.

The lingering controversy between Keynesians and monetarists persists even today – about the cause, length, and depths of the Great Depression – was it the result of bad monetary policy carried out by the Federal Reserve Board in the United States, according to Friedman, or the outcome a worldwide series of accidents dating from World War I, in MIT’s Paul Samuelson’s view?

The citation states:

“To be clear, Bernanke’s analysis does not engage in the discussion of what caused the initial economic downturn in the late 1920s that subsequently escalated into the Great Depression, and this was not the focus of Friedman and Schwartz either. Similarly, when we discuss the Great Recession below, the core issue is not about its origins but on the mechanisms by which the recession played out.’’

Whatever the case, though, Bernanke stated his own view when, in 2002, in an important speech as a governor of the Fed at a celebration for Friedman’s 90th birthday, he concluded:

“Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.”

The citation, however, sticks to what happened in 1983:

“From the perspective of the contributions by Diamond and Dybvig, Bernanke’s work can be seen as providing evidence supporting their models. Specifically, he provides evidence that bank runs can lead to financial crises (as in Diamond and Dybvig, 1983), which in turn leads to prolonged periods of disruption of credit intermediation, consistent with bank failures destroying the valuable screening and monitoring services banks perform (as in Diamond, 1984).’’

Thus the guest list for this year’s prize celebration includes Bernanke, Diamond and Dybvig. Perhaps the authorities will find a seat as well for Stanley Fischer, former president of the Bank of Israel. But the honored ghosts whose earlier work the three displaced will be present as well: Modigliani and Miller; Samuelson, Friedman and Anna Schwartz, Only Dr. Schwartz failed to receive the ultimate diploma, but then the centrality of A Monetary History was not yet apparent in 1976, neither was the extent of her contribution to it, when Friedman received his prize.

As for what happened in 2008, the prize citation has nothing to say. Wall Street Journal columnist Greg Ip noted that “Outside of a footnote, the committee managed to ignore Mr. Bernanke’s central role in responding to that crisis.’’ The Swedes chose to tell the story from its beginning, instead of its end. What, then, did we learn from the 2008 crisis? We’ll have to wait a little longer for that prize.

Meanwhile, what about that sixth Specter, the uninvited guest at the banquet?

That would be Martin Shubik, of Yale University, a long-time player in the Nobel nomination-league, who supervised both Diamond and Dybvig in their graduate studies. Shubik himself had worked, for a dozen years without conspicuous success, on the more forbidding problem of integrating the production of money and banking into the market system Not long before he died, he believed he had solved it. A paperback edition of (2016), with Eric Smith, appears next month.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville, Mass.-based economicprincipals.com.

Fast trash spreaders

Delicious way to boost your blood sugar but where will you put the bag?

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s usually a debate in this or that community around here about whether to let such chain fast-food establishments as Canton, Mass.-based Dunkin’ Donuts open stores there. I’m sympathetic to those residents who want to keep them out.

Of course, one reason to oppose them is that they tend to drive some locally based businesses out of business.

Another is that they are serious outdoor-trash spawners. I’m not sure if Dunkin’ Donuts customers are bigger slobs than the rest of us, but their coffee cups, lids, bags and so on are all over the place and have been at a generally increasing rate since the company’s founding, in 1948.

Mike Freeman: The mysterious and alarming decline of muskrats - much needed waterway engineers

Muskrat feeding.

— Photo by mikroskops

No one would call muskrats “charismatic megafauna.” They’re pudgy, small and just rat-like enough. Semiaquatic, they inhabit sloughs, creeks, and swamps people rarely visit. Muskrats have been considered so prevalent and unremarkable that even people in tune with environmental goings-on have been unaware of the species’ 50-year decline. Biologists noted the nationwide trend early through trappers’ harvest data, but earnest study is a recent phenomenon.

“It would be like robins suddenly declining,” said John Crockett, a University of Rhode Island graduate student studying the state’s muskrat distribution. “No one ever thought muskrats would be in trouble.”

Muskrat lodge built from vegetation

In trouble they are, though, with unsettling implications. The first of these are the animals themselves and their ecological role. Muskrats feed on wetland vegetation and build covered winter “lodges” from it. This opens wetlands up, thinning plants such as cattails and bulrushes to create what Crockett called “patchy ecosystems” that sustain greater biodiversity, the way big wind events, pest outbreaks, and managed timber cuts open forests to new growth, attracting different suites of birds and plant communities than uniform woodlands.

With dwindling muskrat populations, dense vegetation blunts water flow, changes oxygen levels, and can pare back fish and invertebrate life.

“Muskrats are crucial wetland engineers,” said Laken Ganoe, another URI Ph.D. candidate, who published a 2020 paper on muskrat decline while at Penn State. “Similar to beavers, their activity can change hydrology, stream bank structure, and help maintain functioning wetlands. They’re also a key prey source for species such as mink, birds of prey, and raccoon. The wetlands they help maintain provide ecosystem services such as water filtration and air purification, and declining muskrat populations can throw these out of balance.”

In southern New England, muskrats inhabit fresh and brackish water, from nameless rills to big rivers to salt marshes. Their increasingly diminished presence is bad enough, but equally worrisome is why it is happening, in large part because that isn’t known.

Laurence C. Smith of the Institute at Brown (University) for Environment and Society has started a DNA study to determine muskrat presence in Rhode Island waterways. He described the current science, which isn’t far beyond the spit-balling phase.

“Researchers are just beginning to study this problem and there are numerous hypotheses being tested, including disease, habitat loss, and climate change,” he said.

Crockett added nuance, saying that habitat fragmentation and isolation are plagues for all species including muskrats, and that ecosystem degradation, including water quality, is another potential culprit. Ganoe’s Pennsylvania study looked at traditional muskrat diseases such as tularemia, along with ailments that might relate to cyanobacteria and legacy industrial chemicals. While she found various levels of concern, nothing resembling a widespread killer turned up. Across the United States and Canada, she said, there seems to be consensus that “there’s not one overarching cause of the decline, but rather a dozen puzzle pieces working in conjunction.”

That muskrats’ woes result from a grim grab bag of sprawl, industry, pollution and climate change is likely, which only compounds the worry, as muskrats have already proven that they are built for the Anthropocene. Highly prolific and mobile, the animals thrived in the notoriously unregulated mid-20th Century, but are listing now. Why is unknown, but muskrats once rated with pigeons and cockroaches as the creatures most likely to survive us, so finding that answer is imperative.

Trapper harvest data isn’t infallible, but biologists gain much from it. Charlie Brown, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s recently retired furbearer biologist, studied harvest data throughout his 31-year professional tenure.

“It’s difficult to rely on harvest data exclusively,” he said. “But it’s valuable. Rhode Island requires exact harvest data in order to renew your license … whereas that information is voluntary in other states, so we have very specific numbers going back to 1949.”

In the 1950s, Brown said, Rhode Island trappers took 10,000 muskrats a year. During the 2019-2020 season, just 47 were killed. Declining trapper numbers affect that, but not enough for a drop that steep.

There’s some counter-intuition to wrestle here. On paper, conditions favor muskrats more now than in the 1950s to ’70s, when wetlands were blithely drained and factories dumped effluent everywhere. In Barrington, R.I., where Brown grew up, a lace dye company made Bullocks Point Cove turn whatever color stain it used that day.

“But muskrats were still there,” Brown said. “And in big numbers.”

Crockett said even today one of the highest muskrat concentrations he has found is on the Pawtuxet River right under Interstate 95.

Wetland acreage, too, has remained stable during the muskrats’ decline period. That marshes are no longer drained and rivers no longer run purple is great news. Yet, muskrats boomed during these conditions and badly falter now.

With research just ramping up, speculation remains the only map. Waters are still loaded with farm and lawn runoff, along with plastic pollution, though no direct evidence currently links these with muskrat decline. Invasive aquatic flora jumps out, too. Smith is testing the replacement of native plants like cattails (Typha) by phragmites, the invasive reeds that now dominate fresh and brackish waters.

“Phragmites creates more sterile wetlands and chokes out open-water patches favored by muskrats,” he said.

Laura Meyerson, a URI professor whose research focuses on invasive species, with a particular emphasis on plants, points to phragmites and other invasive flora as potential reason for muskrat decline.

“Water chestnut is particularly nasty,” she said. “It grows floating mats that have little nutritional value. In fresh and salt water, phragmites has outcompeted Typha. Muskrats rely on Typha for their carbohydrate-rich rhizomes [roots] and the leaves and stems to build their lodges.”

Mike Freeman is an ecoRI News contributing reporter.

Ebb and flow about issues

“Ebb & Flow” (encaustic on panel and lead), by Rockland, Maine-based painter Kim Bernard.

She says:

“I create work that is for the public, uses recycled materials, is interactive and kinetic, involves the community in the making and raises awareness about environment issues and social causes. I am particularly interested in working creatively with high-risk youth, engaging them in hands-on projects that encourage creative problem solving, collaboration, skill building and self-esteem.’’

Rockland Breakwater Light.

— Photo by Needsmoreritalin

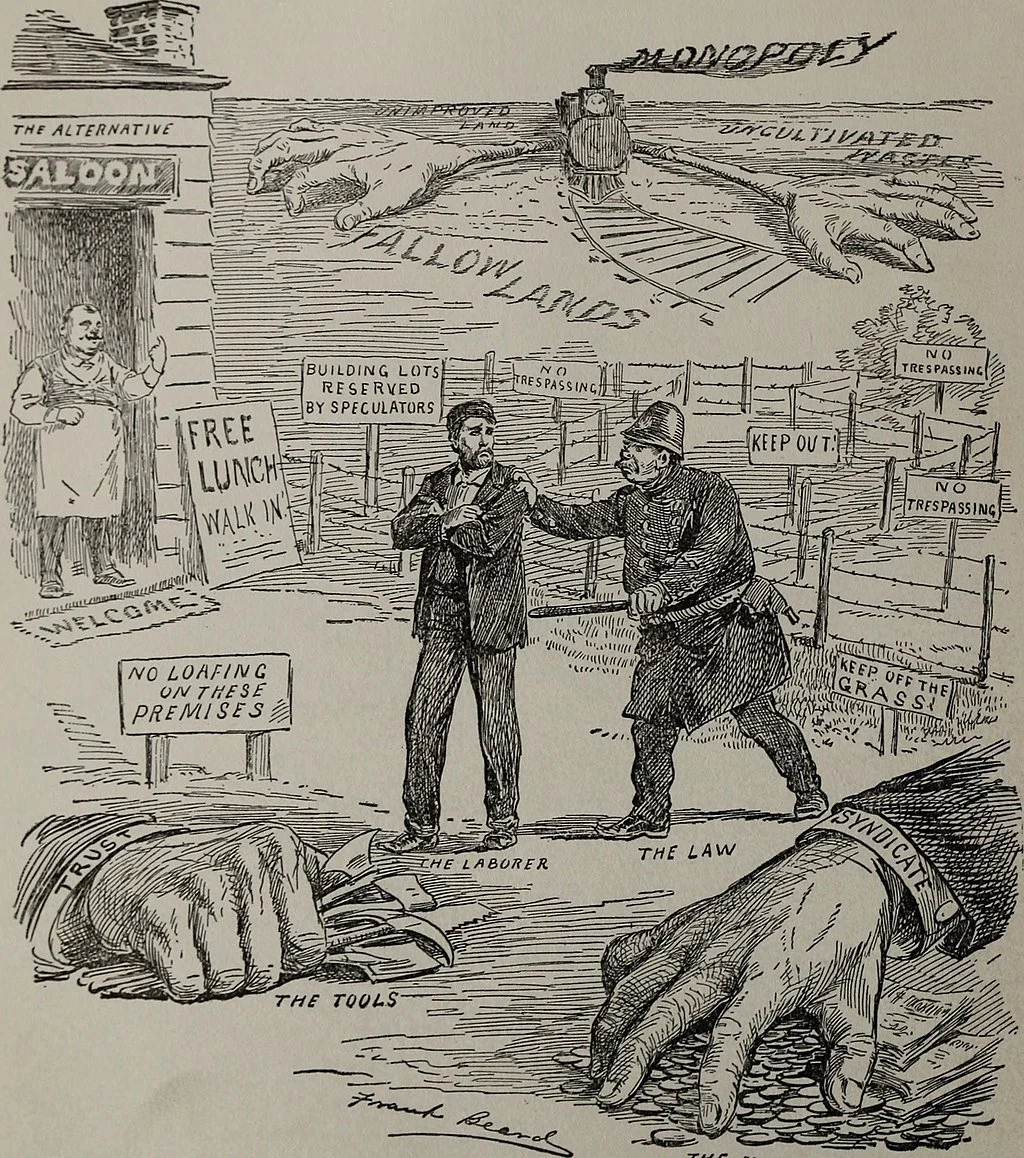

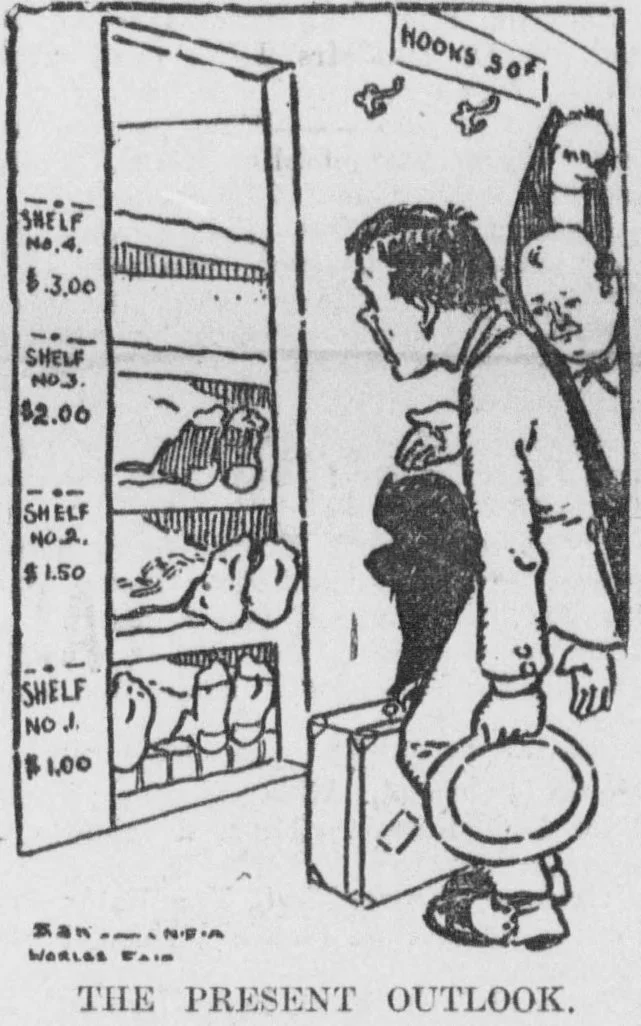

Jim Hightower: Inflation -CEO's brag about their price gouging

1904 cartoon warning attendees of the St. Louis World's Fair of hotel room price gouging.

Via OtherWords.org

Publicly, they moan that the pandemic is slamming their poor corporations with factory shutdowns, supply-chain delays, wage hikes and other increased costs. But inside their boardrooms, executives are high fiving each other and pocketing bonuses.

What’s going on? The trick is that these giants are in non-competitive markets operating as monopolies, so they can set prices, mug you and me, and scamper away with record profits.

In 2019 for example, before the pandemic, corporate behemoths hauled in roughly a trillion dollars in profit. In 2021, during the pandemic, they grabbed more than $1.7 trillion. This huge profit jump accounts for 60 percent of the inflation now slapping U.S. families!

Take supermarket goliath Kroger. Its CEO gloated last summer that “a little bit of inflation is always good in our business,” adding that “we’ve been very comfortable with our ability to pass on [price] increases” to consumers.

“Comfortable” indeed. Last year, Kroger used its monopoly pricing power to reap record profits. Then it spent $1.5 billion of those gains not to benefit consumers or workers, but to buy back its own stock — a scam that siphons profits to top executives and big shareholders.

Or take McDonald’s. It bragged to its shareholders that despite the supply disruptions of the pandemic and higher costs for meat and labor, its top executives had used the chain’s monopoly power in 2021 to hike prices, thus increasing corporate profits by a stunning 59 percent over the previous year.

And the game goes on: “We’re going to have the best growth we’ve ever had this year,” Wall Street banking titan Jamie Dimon exulted at the start of 2022.

Hocus Pocus. This is how the rich get richer and inequality “happens.”

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker.

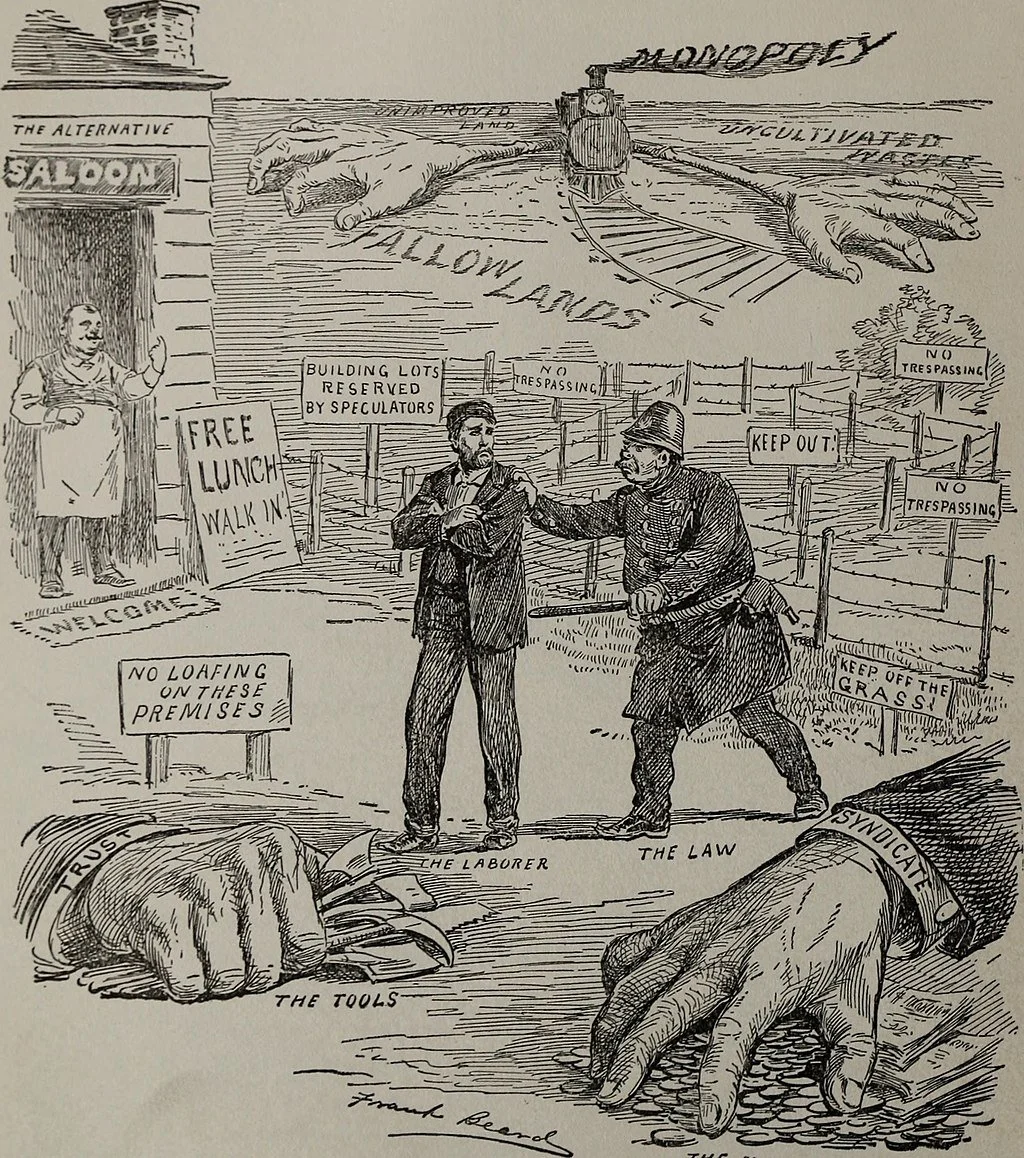

1902 cartoon

'Sameness and difference'

”Reconfiguration #2’’ (acrylic on canvas), by Rupert, Vt.-based artist Jane Davies, at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

She says on her Web site:

“No matter what format or style my work takes, the pivot point of my visual explorations is sameness and difference. I like assembling a collection of visual elements that are markedly different from each other, like putting together a dinner party of people that have wildly different backgrounds and interests, to see what happens. I want to be surprised by the conversations or juxtapositions of my visual cast of characters, and then see how I can relate them to one another formally.’’

Anthropomorphic architecture

“This old house which was hers

made her crooked back a shingle,

her covered eye this fireplace oven,

her arms the young pine beams

now our clapboard siding….”

— From “The Families Album,” by Michael S. Harper (1938-2016), American poet and Brown University professor

‘Lambent incandescence’

— Photo by David Ohmer

”The water was palpably soft, and floating with the current we were invisible in the wispy layer of fog. Then, in what seemed like a flash, the sun hit the river and the fog disappeared. The surface was completely still, and looking toward shore I saw, as if below me in the dark water, a buried valley of lambent incandescence. Looking above the bank I saw what at first seemed to be, in that ethereal atmosphere, a reflection of what the water held.’’

— Jerrold Hickey (1922-2007), on his “earliest memory of fall foliage,’’ along the Charles River in Newton, Mass. This is from an essay he wrote for Arthur Griffin’s New England: The Four Seasons (1980)

Llewellyn King: For fairness and privacy, bring back cash

Once at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco, I went to check in, and when I reached for my wallet it wasn’t there. The clerk said that I wouldn’t be able to check in without a credit card.

I explained that I had, mercifully, in another pocket, enough cash to pay for the stay. Reluctantly, they took more than enough of it for the two days and made a big point of telling me not to sign for even a cup of coffee.

Nowadays, I doubt they would accept my cash deposit.

Real people carry credit cards. Non-people — a subspecies of the American customer — are without. Woe to those.

Today there are more of these non-people because one of the lasting effects of the COVID pandemic is that cash is out, and plastic is all. No plastic, no go.

Hotels, airlines and even coffee shops have gone cashless. Ostensibly, this is because it is healthier. Truthfully, they don’t want to be bothered. Cash is a problem; credit is easier. In fact, from the vendor’s point of view, cash sucks, credit is cool.

At a large hotel in Orange County, Calif., where I have been attending a conference, I tried to buy a coffee at Starbucks. “I don’t take cash,” said the barista, primly. “Just credit cards and room service.”

This caused me to wonder again about the legions of Americans who don’t have credit cards, some of whom don’t want them, but most don’t have credit or have been turned down.

If we have a recession, which now seems inevitable, there will be more people without credit and immobilized by the post-COVID realities of the plastic-favored world.

Cash on hand won’t save them. They are the unbanked, a lesser order of our citizenry.

For starters, millions of the working poor are mostly without credit. It is hard to worry about the niceties of credit when you struggle to get food to the table for the family.

In this new world, the cardless also are immobilized.

Consider what being without plastic means: You can’t make a reservation on Amtrak or an airline. You must go to an airport, as airlines no longer have free-standing ticket offices. Then you will learn that you must use a reverse ATM to buy a card with cash to buy a ticket. Amtrak still takes cash, but you must go to a railroad station.

The first consequence is, in most cases, you will pay a lot more if you try to buy the ticket on the day of travel. Those tempting “book now and save” ads are only for credit card holders.

You can’t get to the railroad station or the airport on a ride-sharing service because they work only with credit cards.

So the luckless, who probably don’t have plastic because of financial problems, will pay more because they will be paying mostly at the last minute, and they will be charged to convert their cash to plastic at the airport. These travelers won’t be able to buy a drink or internet service because that requires you to file a credit card before you board.

It is an old story: the poor pay more. Now they may not be allowed to pay with the currency of the land.

An odd byproduct of the move to plastic is a further blow to privacy. Cellphones and security cameras have already stripped away much of our privacy. Will the fact that this very morning I bought a latte and a croissant with a credit card cause me to be inundated with Internet advertisements for designer coffee and pastry?

What would the deduction be by a suspicious partner if the credit card bill showed two lattes and two croissants?

Bring back cash. It was universal, left no record, and was preferred by merchants. Now they don’t want it, even for a coffee.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Inside Sources

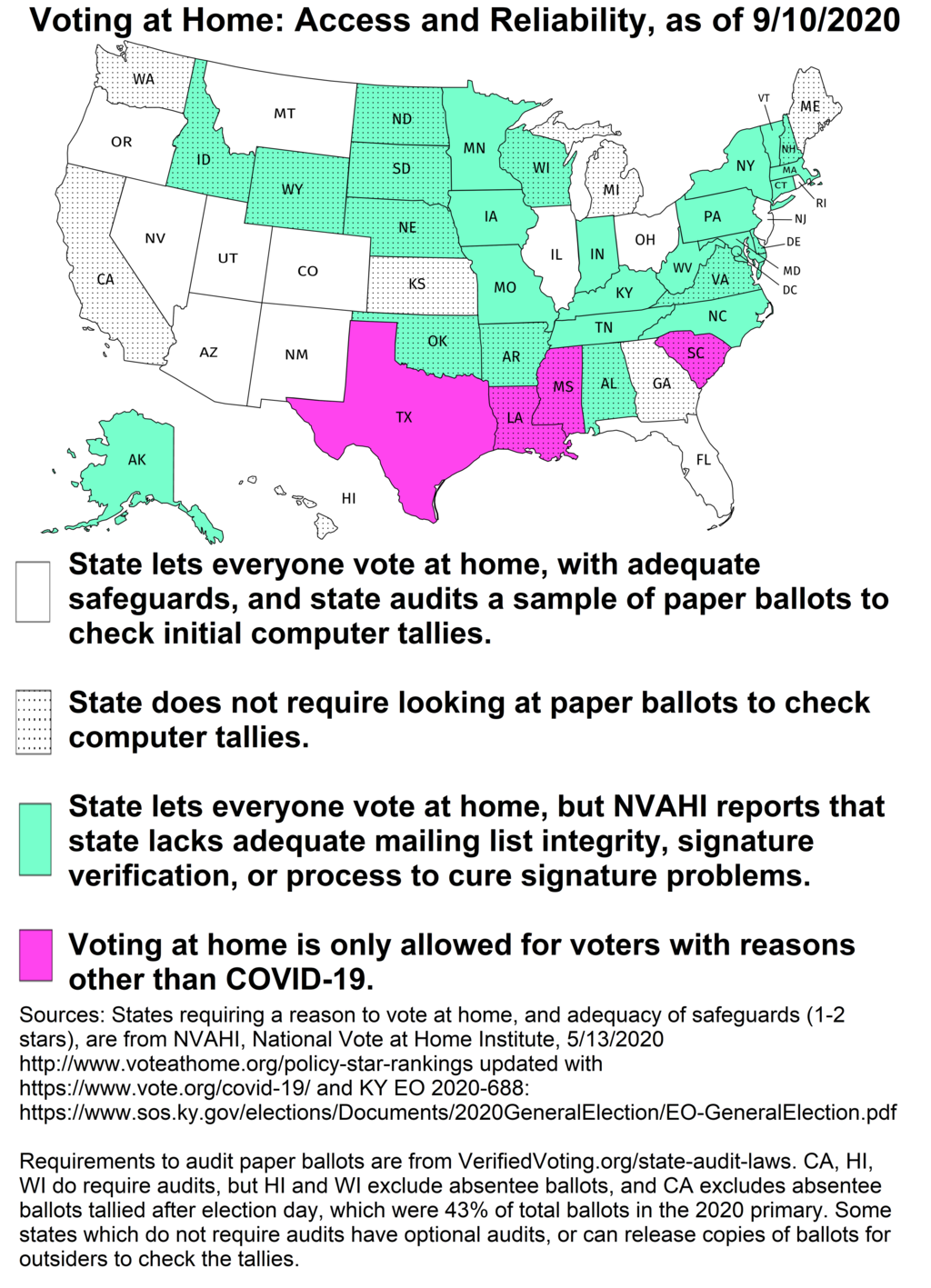

Chris Powell: Absentee-voting expansion is invitation to fraud; will Title IX be erased by trans-athlete movement?

Early voting in U.S. states, 2020

— Graphic by J.Winton

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Election officials throughout Connecticut are properly worried by the sharp increase in absentee-ballot applications being requested by political campaigns and distributed to voters who have not requested them. The practice will cause confusion and facilitate fraud.

Anyone can request an absentee-ballot application for himself or others, and applications can be downloaded from the secretary of the state's Internet site or obtained from a municipal clerk's office. Applications are to be signed by the voter and delivered to the municipal clerk's office, which will hand the voter an absentee ballot or mail one to him. The voter is to complete it, put it in a secure envelope, sign the envelope, place the ballot envelope inside a mailing envelope, and mail or deliver the ballot package to the municipal clerk.

It's a good system for protecting ballot confidentiality. But an absentee voter never has to appear in person before any election official. Nor, as a practical matter, does an absentee voter even have to live in the municipality in which he would vote, nor even still be alive. Of course, the law requires that much but seldom does anyone check. As long as a voter's name remains on the voter rolls, an absentee ballot can be cast in his or her name.

That's why the mass collection and distribution of absentee-ballot applications by political campaigns is so risky. Campaign workers familiar with their towns are able to discern which people on the rolls pay attention and vote regularly and which don't, and the latter become the target for voting fraud.

Indeed, most election-fraud controversy involve absentee ballots, since the absentee-ballot process inevitably separates a voter from the casting of his vote. The ongoing litigation over the Democratic primary for state representative in the 127th House District has revealed one absentee-ballot fraud and screw-up after another. But in-person voting at polling places, where voters must produce identification and complete and cast their ballots in the presence of election officials, is almost impossible to corrupt.

Increasing the security of absentee ballots would be difficult. Being posted on the Internet, the absentee ballot form is available to anyone at any time and can be printed and distributed in infinite numbers.

To confirm that absentee-ballot requests are genuine, election officials could be required to make personal contact with applicants, by telephone or face-to-face interview, but the expense would be great. As a practical matter, probably the most that can be done is to minimize causes for use of absentee ballots and minimize the handling of ballots and applications.

State law authorizes the use of absentee ballots in six circumstances, all of them sensible. But it might be good for the law to restrict any person from distributing more than two absentee-ballot applications, thus taking candidates and campaign workers out of the absentee ballot business.

Of course it would be difficult to police such a restriction, but candidates and campaign workers still could encourage voters to obtain absentee-ballot applications on their own, since it could hardly be easier.

In any case, the less in-person voting, the more election fraud.

xxx

For many years society and the federal government, as codified in Title IX of federal civil rights law, presumed that there were two sexes, male and female; that in general males were physically stronger; and, as a result, that fairness required publicly financed institutions operating competitive sports programs to maintain programs exclusively for women, programs that were equal to those provided for men, for otherwise athletic opportunity for women would tend to be diminished.

Not any more. Lately government, under the pressure of a bizarre new ideology, sustained by political correctness, is presuming that there is no physical difference between the sexes, that men can become women and women can become men just by thinking it , and that men and boys who think themselves women must be permitted to compete against women and girls in athletic events.

In a case arising from Connecticut, the issue of men participating in women's sports -- the nullification of Title IX and the progress achieved thereunder -- has reached a federal appellate court. The law may change but biology won't.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester (CPowell@JournalInquirer.com).

Cross-species and cross-cultural communication

“Inside the Belly of a Rabbit’’ (watercolor on paper), by New York-based artist Dana Sherwood, in the show “Dana Sherwood: Some Kind of Tea Party or Thereabouts in the Realm of Madness,” at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth’s University Art Gallery, in downtown New Bedford, through Dec. 28.

© Dana Sherwood

The gallery says:

“This exhibition, which includes films, ceramics, oil and watercolor paintings, explores the relationship between humans and the natural world, drawing on the artist’s exploration of cross-species communication, domestic culture, and the mythical connections between the feminine and natural world in a changing environment.’’

“Gosnold at the Smoking Rocks” (oil on canvas, 1842), by William Allen Wall, at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. It’s a romanticized depiction of English explorer Bartholomew Gosnold meeting a few of the local Wampanoag people in 1602. Gosnold (1571-1607) was said to be the first European to set foot in what’s now called New Bedford.