‘The Yankee-est gal’

Better Davis (at age 79) in The Whales of August (1987), which brought her acclaim during a period in which she was beset with failing health and other personal crises. The movie is set in Maine.

“To fulfill a dream, to be allowed to sweat over lonely labor, to be given the chance to create, is the meat and potatoes of life. The money is the gravy. As everyone else, I love to dunk my crust in it. But alone, it is not a diet designed to keep body and soul together.’’

— Bette Davis (1908-1989), movie star and writer, in her 1962 memoir The Lonely Life

She called herself the “Yankee-est gal who ever came down the pike.”

She was born and educated in Massachusetts, married three New Englanders and had homes in Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine.

No conditioner needed

“Hirsute Queen Eumelanin” (human and synthetic hair, Black-Faced Sheep horns, tanned and dyed fish skin), in Cambridge, Mass.-based Jenn Levatino’s show, “The Keratin Series,” at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through Oct. 30. These drawings and sculptures are inspired by animal remains and hairstyles in ancient Roman portraiture.

David Warsh: Exploring ‘quantum weirdness’

Main building of the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, in Stockholm.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I spent its time last week reading up quantum entanglement. Instantaneous connections between far-apart locations – the possibility of “spooky action at a distance” that was dismissed by Einstein – turns out to have become the basis of quantum computing and fail-safe cryptography.

First I read The New York Times story: Nobel Prize in Physics Is Awarded to 3 Scientists for Work Exploring Quantum Weirdness. by Isabella Kwai, Cora Engelbrecht and Dennis Overbye. I especially liked the part about John Clauser’s duct-tape and spare-parts experiment in a basement at the University of California at Berkeley that opened the laureates’ path to the prize. (Stories in The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times each had distinctive strong points as well.)

The Times story led me back to MIT physicist/historian David Kaiser and his 2011 book, How the Hippies Saved Physics: Science, Counterculture, and the Quantum Revival. I didn’t read it when it appeared, having a mild prejudice against hot tubs, psychedelic drugs and saffron robes. I was wrong. I ordered a copy last week.

Next was a Science magazine piece from 2018 by Gabriel Popkin that showed the discoveries well on their way to acceptance: Einstein’s ‘spooky action at a distance’ spotted in objects almost big enough to see.

Then came a Scientific American article, The Universe Is Not Locally Real, and the Physics Nobel Prize Winners Proved It, by David Garisto, that seemed to me to offer the most lucid explanations of the profound uncertainties involved. These are more daunting than ever in the face of irresistible technological evidence that they exist.

At that point I returned to the Nobel announcement, and skimmed the citations in the scientific background to see if the story was as I had been taught (by my mother, Annis Meade Warsh, who was herself entangled with science and religion!). Sure enough there among the citations was the history of the argument, from Erwin Schrödinger, in 1935; to Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen, in 1935; to David Bohm, in 1951; to John Stewart Bell, in 1964; and to Stuart Freedman and Clauser (the former having been Clauser’s graduate student), in 1972. Imagine my surprise last year when I discovered the distinguished historian of physics John Heilbron was reading Bohm’s last book, Wholeness and the Implicate Order, the very title recommended to me by my mother not long after its publication, in 1980. I checked Wholeness out from the library. I could not fathom the implicated order.

In fact, the most beguiling explication of the prize I found was the 15-minute talk that Nobel Committee member Thors Hans Hansson gave to journalists after the prize announcement in Stockholm last week. The 72-year old theoretical physicist personified the combination of collective energy, sobriety and delight that enables the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to keep the world abreast of developments, year after year.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Chris Powell: Students' vacuous righteousness; abortion phonies; stupidly erasing criminal records

Central Connecticut State University

MANCHESTER, Conn.

With a protest march on campus the other day, students at Central Connecticut State University, in New Britain, showed the world that they haven't learned what even kids in elementary school might be expected to know.

The students demanded that the university administration investigate a fellow student's complaint of sexual assault that had not yet been made formally to any police agency or to the university itself.

Instead, the accusation had been made by the complainant only on a social- media internet site, TikTok, which may be best known for posting videos encouraging young people to do stupid, dangerous, damaging, and even criminal things to get attention, the infamous "TikTok challenges."

As it turned out, the university had heard of the accusation on TikTok prior to the student protest march and already had hired some outsiders to investigate, the campus police and New Britain police apparently being considered incompetent.

Having handled the matter in such a strange way, the university was in no position to remind the student protesters that if you want the authorities to act against crime, the first thing to do is to report it to them. Central's campus is dotted with emergency telephone stations, and most young people these days would leave home in the morning without their shoes before they left without their mobile phones. But of course holding a protest march before there is anything to protest provides a rush of self-righteousness.

xxx

U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal, the Connecticut Democrat seeking election to a third term, isn't the only candidate for senator who is dissembling on the abortion issue.

Blumenthal says his abortion legislation in Congress, the Women's Health Protection Act, would simply put into federal law the policy articulated by the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Roe v. Wade. But the Roe decision held that states properly could prohibit or regulate abortion after the viability of the unborn child, while Blumenthal's legislation would prohibit states from restriction abortion at any stage of pregnancy.

Blumenthal's Republican challenger, Leora Levy, recently deflected a request from Connecticut's Hearst newspapers to say what she thinks about South Carolina Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham's legislation to outlaw abortions nationally after 15 weeks of gestation.

Levy used to support abortion rights. But during the primary campaign for the Republican Senate nomination, Levy declared herself to be completely anti-abortion and explained in detail why she had changed her mind. Now she seems to be changing her mind again.

“I am personally pro-life and I support exceptions for rape, incest and the life of the mother," she said in response to the inquiry from the Hearst papers about Graham's legislation. "When I am elected to the Senate, I will be accountable to the people of Connecticut for my votes and positions.”

That is, fervent opposition to abortion is helpful in winning a Republican primary but not in winning an election. Levy is so principled on abortion that she now wishes the issue would just go away. Yes, Levy will be accountable for her positions after the election -- when it's too late for voters to do anything about being misled.

xxx

Erasing criminal records, thereby diminishing accountability from criminals, and increasing accountability from police officers have become great causes on the political left in Connecticut. The resolution of a recent case in Hartford Superior Court showed that the first cause can defeat the latter.

Over the objections of a prosecutor, Superior Court Judge Stephanie A. Damiani admitted a former Glastonbury police lieutenant, Kevin Troy, to two diversionary programs as he faced charges of drunken driving and interfering with police. Troy had gotten drunk, caused a rollover crash in Enfield, and then lied to police about it, telling them that someone else had been driving. Troy's completion of the programs will erase the records of his offenses.

Troy retired from the Glastonbury department after his arrest but is only 49 and might seek to return to police work elsewhere. With his criminal record erased, a big impediment to that will be out of the way.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Gold goes

October turned my maple’s leaves to gold;

The most are gone now; here and there one lingers.

Soon these will slip from out the twig’s weak hold,

Like coins between a dying miser’s fingers.

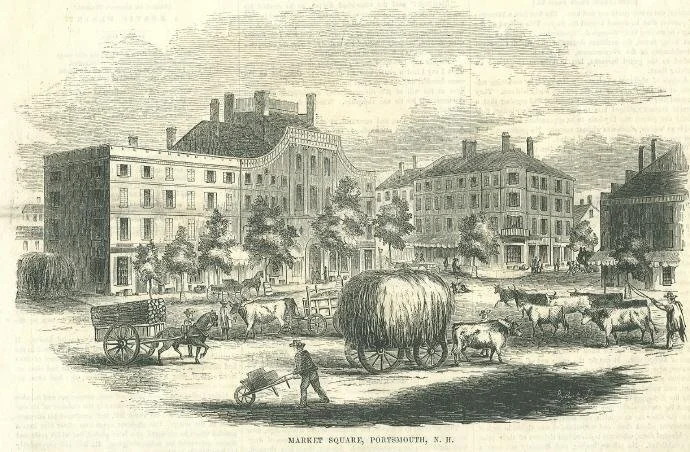

“Maple Leaves,’’ by Thomas Bailey Aldrich (1836-1907), American editor (including of the Boston-based Atlantic Monthly) poet, critic and native of Portsmouth, N.H., about which he wrote with affection.

I 853 print

Mysteries of Monhegan

1909 postcard

“Monhegan {Island} is known to be the resort or asylum of pirates, smugglers, or mutineers, centuries ago. If what we do not know about could be unearthed, what an interesting chapter it would make.’’

Samuel Adams Drake (1833-1905), in The Pine-Tree Coast

Daniel Chang/Lauren Sausser: Coastal hospitals under growing threat from hurricanes

Massachusetts General Hospital, in flood-prone Boston. A study published in GeoHealth of hospitals in 78 urban areas along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts assessed by researchers ranked Boston third most vulnerable — behind Miami and New York — to damage from flooding and other threats from hurricanes.

As rapidly intensifying storms and rising sea levels threaten coastal cities from Texas to the tip of Maine, Hurricane Ian has just demonstrated what researchers have warned: Hundreds of hospitals in the U.S. are not ready for climate change.

Hurricane Ian forced at least 16 hospitals from central to southwestern Florida to evacuate patients after it made landfall near the city of Fort Myers on Sept. 28 as a deadly Category 4 storm.

Some moved their patients before the storm while others ordered full or partial evacuations after the hurricane damaged their buildings or knocked out power and running water, said Mary Mayhew, president of the Florida Hospital Association, which coordinates needs and resources among hospitals statewide during a hurricane.

About 1,000 patients across five Florida counties were evacuated from hospitals for different reasons, Mayhew said, with one hospital moving patients after the storm tore part of its roof and deluged the ground floor. Other hospitals emerged with no structural damage but lost power and running water. Broken bridges, flooded roads, and lack of clean water all added to the challenge for some hospitals, Mayhew said.

And that’s before considering the need to help those injured in the hurricane and its aftermath.

“Climate shocks like hurricanes show us in the most painful way what we need to fix,” said Aaron Bernstein, interim director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment, known as C-CHANGE, at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

As climate change increases the intensity of hurricanes, coastal cities threatened by rising sea levels from Miami to Charleston, S.C., have considered billion-dollar storm surge protection plans — from elevating homes to creating a network of seawalls, floodgates, and pumps to protect residents and infrastructure against powerful flooding from storms.

Some hospitals are fortifying buildings and elevating campuses. Others are moving inland, as they prepare for a future when even weak storms unleash flooding that can overrun facilities.

“They’re the front lines of climate change, bearing the costs of these increased weather events as well as the increase in injuries and disease that come with them,” said Emily Mediate, U.S. climate and health director for Health Care Without Harm, a nonprofit that works with hospitals to prepare for climate change.

Yet even as hospitals prepare for extreme weather, Bernstein and a team of researchers at Harvard predicted in a recent study that many facilities along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts will face a suite of problems, even from milder weather events.

The study analyzed the flood risk to hospitals within 10 miles of the Atlantic and Gulf coastlines. In more than half of the 78 metropolitan areas analyzed, some hospitals are at risk of storm surge flooding from the weakest hurricane, a Category 1. In 25 coastal metro areas, half or more of the hospitals risk flooding from a Category 2 storm, which would have winds of up to 110 mph. Florida is home to six of the 10 most at-risk metropolitan areas identified in the study, with the Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach region ranked as having the greatest risk of hurricane impact.

Researchers also considered the risk of flooding for roads within 1 mile of coastal hospitals during a Category 2 hurricane. That’s what happened on Florida’s western coast, where Hurricane Ian’s maximum sustained winds of 150 mph contributed to flooded roads and washed-out bridges.

All three hospitals in Charlotte County were closed during the storm. One reopened its emergency room the following day, and two were operational by Oct. 1.

In neighboring Lee County, the public hospital system was forced to partially evacuate three of its four hospitals, potentially affecting about 1,000 patients, after the facilities lost running water. As of Oct. 6, the county remained in a state of emergency and many roads and bridges were closed due to flooding and damage, according to the Florida Department of Transportation’s traffic information.

Several Florida hospitals on waterfront property have moved their essential electrical systems and other critical operations above ground level, elevated their parking lots and buildings, and erected water barriers around their campuses, including Tampa General Hospital, which has the only trauma center in west-central Florida.

Miami Beach is a barrier island where roads flood on sunny days during extremely high tides. Building to withstand hurricanes and flooding is a priority for institutions, said Gino Santorio, CEO of Mount Sinai Medical Center, which sits at the edge of Biscayne Bay.

Over the past decade, Mount Sinai has completed nearly $62 million in projects to protect against hurricanes and flooding. The projects were part of a countywide strategy funded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency and state and local governments to fortify schools, hospitals, and other institutions.

“It’s really about being the facility of last resort. We’re the only medical center and emergency room on this barrier island,” Santorio said.

But Bernstein said the “Fort Knox model” of spending hundreds of millions of dollars on state-of-the-art hurricane-proof hospital buildings isn’t enough. This strategy doesn’t address flooded roads, transportation for patients ahead of a storm, medically vulnerable people in areas most at risk of flooding, emergency hospital evacuations, or the failure of backup power sources, he said.

Urging hospitals to fortify for more severe hurricanes and rising sea levels can feel overwhelming, especially when many are struggling to recover from pandemic-related financial stress, labor shortages, and fatigue, said Mediate, of the group Health Care Without Harm.

“Lots of things make it hard for them to see this is a problem, of course. But on top of how many other issues?” she said.

As Hurricane Ian approached the South Carolina coastline north of Charleston on Sept. 30, the city’s low-lying hospital district reported about 6 to 12 inches of water. “That’s much less than was expected,” Republican Gov. Henry McMaster said during a news briefing.

Though Hurricane Ian was a relatively minor weather event in South Carolina, it’s not unusual for Charleston’s downtown medical district to flood, making it dangerous and, sometimes, impossible for patients, hospital employees, and city residents to navigate surrounding streets.

In 2017, the Medical University of South Carolina ferried doctors across its large campus on johnboats during severe flooding from Hurricane Irma. One year later, the Charleston-based hospital system bought a military truck to navigate any future floodwaters.

Flooding, even after heavy rain and high tide, is one reason Roper St. Francis Healthcare — one of three systems in Charleston’s downtown medical district — announced plans to eventually move Roper Hospital off the Charleston peninsula after operating there for more than 150 years.

“It can make it very challenging for people to get in and out of here,” said Dr. Jeffrey DiLisi, CEO of Roper St. Francis.

The hospital system sustained light flooding in one of its downtown medical office buildings from Ian, but it could have been much worse, said DiLisi. He also said that the downtown district is no longer the geographic center of Charleston and that many patients say it’s inconvenient to get there.

“The further inland, the less likely you’re going to have some of those problems,” he said.

Unlike Roper St. Francis, most coastal nonprofit and public hospitals have chosen to remain in their locations and reinforce their buildings, said Justin Senior, the president of the Safety Net Hospital Alliance of Florida and a former secretary of the state’s Agency for Health Care Administration, which regulates hospitals.

“They’re not going to move,” Senior said. “They’re in a catchment area where they’re trying to catch everyone, not just the affluent but everyone.”

Daniel Change and Lauren Sausser are Kaiser Health News reporters.

Daniel Chang: dchang@kff.org, @dchangmiami

Lauren Sausser: lsausser@kff.org, @laurenmsausser

Bad and good news-media news

“Reading the Newspaper,’’ sculpture in Brookgreen Gardens, on Pawleys Island, S.C.

— Photo by Pollinator

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Timothy Buckley, Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker’s chief of staff, is right when he complains that the shrinkage of the corps of news-media people is worsening the herd-mentality problem in journalism. Reporters who have survived the slashing of journalistic resources in the past two decades are too few and too busy to do what they should be doing: looking at a wide and ever-changing range of topics and being leery of the conventional wisdom (which in my experience is usually wrong).

And Mr. Buckley noted to Commonwealth Magazine that the news-resource crisis leads to less analysis and nuance in coverage overall.

Consider the recent 30-day closure of the MBTA Orange Line for repairs was presented as though it could be as catastrophic as a hurricane. Smaller outlets followed the big ones, most notably The Boston Globe and public radio, in seeing the shutdown as perhaps, in The Globe’s phrase, “a new circle of hell.’’ In fact, the shutdown, during which the T offered commuters alternative options – mostly buses – caused much less disruption than the apocalyptic warnings had suggested.

Another result of the shrinkage of what used to be usually called “the press corps’’ (not so many presses anymore!) is that far fewer things are watched. It’s easier to just report on what everyone else is covering, taking the lead from the big boys. And yet, as Bill Kreger, a long-departed editor of mine at The Wall Street Journal, once told me: “What may turn out to be the biggest story of the year may start out as three paragraphs at the bottom of page 11.’’

We need far more local news outlets, be they print or online. But the old ad-based business model continues to falter.

xxx

In a happier report on the news business, my GoLocal colleague Rob Horowitz reports that the use of social media as a source for news has stalled, and for good reason. He writes:

“It is the case that some of the plateauing of social media as a source for news is a result of a general slowing in the growth of the use of social media generally. But that is only part of the story. The increased awareness of the amount of disinformation and misinformation available on and spread through social media has resulted in social media becoming a less trusted source of news than other media platforms. This distrust is a major reason for the curbing of social media’s growth as a source for news. {Russia and other malign dictatorships have long used social media as a tool for undermining their foes and propping up the likes of people like Trump who are likely to collaborate with them.}

A Reuters Institute study found that the “levels of trust in news on social media, search engines, and messaging apps is consistently lower than audience trust in information in the news media more generally.’’

Good.

Hit these links:

https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2021

Deeper than a silver surface

“Surface Calligraphy” (acrylic on abraded aluminum), by David Kessler, in the show “American Realism Today,’’ at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of Art, through Jan. 1.

The museum says:

“Capturing scenes of the landscape and everyday life, the show celebrates the rich tradition of Realist art in America while reflecting the innovative spirit of our contemporary times.’’

The show has more than 50 paintings, sculptures and works on paper by a network of 21 artists.

Where they drank and she started to go crazy

Sign on building in Antibes, France, on the Riviera. They lived in a lot of places, including in Westport, Conn., in the summer of 2020. They partied a lot there, too.

— Photo by Chip Benson

New MIT device can help Parkinson’s patients

Views of a man portrayed to be suffering from Parkinson's disease. These are woodcut reproductions of two collotypes from Paul de Saint-Leger's 1879 doctoral thesis, “Paralysie agitante..etc.”

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“New England Council member the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has created a device that can assist patients with Parkinson’s disease. The system can work as a proactive way to gauge if someone has Parkinson’s disease as well as monitor patients by tracking how they walk.

“The device uses a radar-like technology with a radio transmitter-receiver installed in a person’s home as a non-invasive treatment option. To test the effectiveness of the device, MIT researchers observed a group of 50 people, 34 of which were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. They found that the receiver collected a grand total of 200,000 observations. From these data, researchers found that they were able to measure the effectiveness of Levodopa, a medication given to patients to manage their symptoms.

This system would minimize Parkinson’s patients’ need to schedule extra appointments as physicians could monitor their patients remotely and review the observation points in order to prescribe the best dosage for medications.

“Dina Katabi, lead professor on the project said, ‘We know very little about the brain and its diseases. My goal is to develop non-invasive tools that provide new insights about the functioning of the brain and its diseases.”’

MIT’s Rogers Building in Boston’s Back Bay in 1901. The school moved to its Cambridge campus in 1916.

Llewellyn King: Woe Britannia!

View of Edinburgh from Blackford Hill

— Photo by Kim Traynor

EDINBURGH

These are trying times for the British, as I am finding on a visit to Scotland with a brief foray south into England. All isn’t right with their world, and there are expectations that the winter will be the hardest to bear since the long-ago days of the end of World War II.

The price of everything is up, with inflation at 10 percent and predicted to top that by as much as double.

Compounding there is a sense that nobody is in charge. The new prime minister, Liz Truss, has had a disastrous beginning with a revolt of the rank and file of her own Conservative Party. She has had to eat her words and, according to the New Statesman, has had the worst imaginable beginning for a new prime minister.

Truss seems to have abandoned traditional conservative principles and that, together with her own wobbly trajectory, has the party worried.

The centerpiece of doubt about the prime minister is a mini-budget that her chancellor of the exchequer, Kwasi Kwarteng, introduced just after she was elected to the leadership. It called for more spending and a cut in the top income tax rate from 45 percent to 40 percent.

This was supposed to encourage business, but even diehard conservatives couldn’t justify a lot of new spending -- needed to ease the burden of energy costs -- while slashing revenue. Rather than making business happy, the proposal sent the pound into freefall and the markets into turmoil.

Truss did a U-turn, a maneuver, according to her many critics, that she has done often in her career.

Another misstep happened as the Conservatives were assembling in the central English city of Birmingham for their annual party congress: The prime minister refused to guarantee that social spending would be linked to the cost of living.

Complex social obligations in Britain are lumped together under the rubric benefit. “No, no, no,” cried the party, including members of the cabinet. Benefit had to be indexed to the cost of living.

But not all of the mess is of Truss’s making. Things were in sorry shape when the previous prime minister, the notoriously articulate but incompetent Boris Johnson, was sacked by the party.

The economy was faltering, labor unrest was building and such issues as education, health care, immigration and the Northern Irish border were demanding strong, deft leadership.

The result has been that the Tories, as the Conservatives are called, are between 14 and 30 points behind the opposition Labor Party in the polls, and they are expecting a drubbing in the next election in two years, unless Truss can pull things together. The somber mood in Birmingham suggests that gloom will turn to doom.

The Truss government is set to massively subsidize heating costs this winter, which promises real hardship across the board, from pubs which are closing at a record rate to middle-class households now digging out the woolies.

The primary fuel for making electricity and for home heating is natural gas, and the price of that has soared over historical levels because of Russia’s war in Ukraine. The subsidy isn’t disputed, but it will take British borrowing to new levels even as interest costs are soaring -- an ugly combination.

Another open issue is how to fix Britain’s beloved National Health Service, which has fallen into an institutional disrepair. Waiting lists are longer than they have ever been even for minor procedures and successive management shakeups haven’t solved the problems. Yet the health service remains the most popular government program in Britain, and Truss will have to produce something more than Band-aids for the NHS if its failures aren’t to be, albeit unfairly, laid to Truss.

Another headache for the embattled prime minister is that organized labor is on the march again. Strikes, euphemistically called industrial action, in Britain are back. The railroads are being hit, and there is some sense that the bad old days when Britain was the Sick Man of Europe, before Margaret Thatcher, may be returning.

There is a backstory that isn’t being aired much in the largely Conservative British newspapers: the huge, self-inflicted wound of Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union, known as Brexit. Its effects are everywhere and there is a complicity in not pointing this out: We voted for it, and we own it. It wasn’t a party vote, so Brexit remains a common guilt.

Long after Truss has gone, Brexit will remain the guiding fact of Britain’s place in the world. A place less certain than at any time in its long history.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

And October alchemy

“Earthly Alchemy’’ (encaustic monotype, ink, pencil, oil pastel on Kitakata), by Worcester-based painter Donna Hamil Talman.

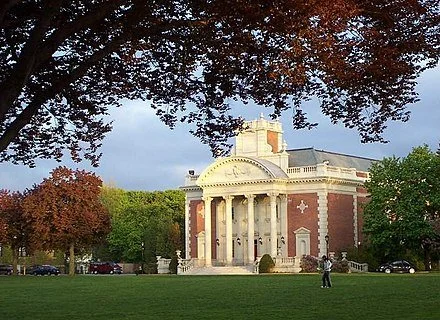

Warner Memorial Theater, at Worcester Academy. Opened in 1932, it was designed by Drew Eberson. The prep school’s famous alumni include computer/lyricist Cole Porter.

Argon art; this old house

“Portrait of Joan” (hand-blown and colored glass tubing, argon gas with mercury transformer), by Laddie John Dill, at the Armenian Museum, Watertown, Mass., in the show “On the Edge: Los Angeles Art 1970’s-1990’s’’

Abraham Browne House, in Watertown, built around 1694. It is now a nonprofit museum operated by Historic New England.

The house was originally a simple one-over-one dwelling and features steep roofing and casement windows, recalling many 17th Century English dwellings. During restoration work in 1919, details of 17th Century finish were found. The ground floor has one large room, which was used for as a sort of living room as well as for cooking and sleeping.

The building may be one of fewer than a half-dozen houses in New England to retain this profile.

— Photo by Wayne Marshall Chase

Mary Lhowe: Going for ‘green burials’

Recent gravesites at Prudence Memorial Park. Soil taken from a grave is mounded on top to create a level surface after settling takes place. The soil is initially removed from the grave and separated by layers, and returned in the same pattern, leaving plant-nourishing topsoil on top.

— Mary Lhowe/ecoRI News photo

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

You couldn’t possibly count the number of places in Rhode Island where you can walk in pure silence except for leaf rustle, moving among drowsing wildflowers, and around shrubs and trees situated by the hand of nature, the landscape free of human objects except for a sliver of a path.

But you can count the number of natural outdoor places that also serve as a functioning cemetery: there is one. It is Prudence Memorial Park, on Prudence Island, a place set aside and developed specifically for green burials, an eco-friendly way to bury the dead that is gaining acceptance across the country.

A green — also called “natural” — burial is one that prohibits embalming with dangerous chemicals, such as formaldehyde. Containers for the body are a simple fabric shroud or a casket of biodegradable material like pine or wicker with no metal fastenings, exotic woods, glues, varnish, or metal fixtures. Finally, in a green burial, there is no concrete underground cement vault or grave liner that the casket sits inside, as in a conventional burial.

That is the basic definition, but a purist definition may go farther. In a green burial, washing and shrouding of the body may be done by family members or friends. Family members may dig the grave by hand. A green burial may take place on private property.

One main driver of green burials is concern for the health of the environment, and also for workers in the funeral industry. Standard embalming fluids contain formaldehyde, which inevitably leach into the ground from the body, and also enter septic systems or sewers straight from a funeral home’s work rooms. These fluids also have been implicated in higher rates of serious illness among funeral home workers. Similarly, varnishes and metal parts of caskets degrade and leach into groundwater.

The exotic hardwoods for fancy caskets are harvested from sometimes-depleted tropical forests and transported around the world at a high cost of fuel. The cement for making underground vaults is a high-polluting material, because of the effects of mining, manufacturing, and transportation.

Green burials are chosen not only by people who want to protect the environment. Some families are turned off by what they see as the excess and expense of fancy caskets and elaborate staging of conventional funerals. Some are looking for an avenue for family members to play a bigger role in the moment, including washing and dressing the body. Some crave quietness and intimacy.

Before green burial started to become known and requested — in the past 10 to 20 years — people sometimes chose cremation because they see it as a cleaner alternative to a full-dress funeral with embalming, tropical-wood casket, and underground vaults. In fact, cremation is a polluting process, in view of the carbon dioxide emissions from the burning. Emissions also contain pollutants from the body, such as mercury from dental fillings and medicines in the tissues.

Ed Bixby, president of the board of the nationwide Green Burial Council (GBC), said lots of ordinary people, not necessarily environmentalists, are asking about green burial. He said families say, “I want something simpler; I want something that feels good; I want my family involved. I want a memorable experience with my loved ones.”

Green burials are conducted by funeral homes across the country, including in Rhode Island. Despite the DIY quality of a green burial, funeral homes are usually enlisted to help with things like securing death certificates and permits, submitting obituaries, hosting a memorial ceremony, finding a biodegradable casket, and arranging for flowers, music and transportation.

In Rhode Island, green burials are done at Swan Point Cemetery in Providence, at Arnold Mills Cemetery in Cumberland, and at Prudence Memorial Park. The first two are “hybrid” facilities, in that they are traditional cemeteries that, in recent years, adapted plots and practices for green burials. Only Prudence is a conservation burial ground.

The park was created and opened for service in 2019 by a three-generation Prudence Island woman who saw a need, pulled on her first pair of work gloves, and went to it.

Island Afterlife

At 5 1/2 square miles, Prudence Island, at the geographical center of Narragansett Bay, is the third largest of the islands in the bay, with only about 150 year-round residents. For people who don’t own boats, the Portsmouth island can be reached only by ferry from Bristol. The island has no businesses, except a small general store.

Robin Weber’s grandfather bought a summer house on Prudence Island, but she and her brother are the first generation to live there year-round. She worked for 20 years as stewardship coordinator for the Narragansett Bay National Estuarian Research Reserve, headquartered on the island.

Also, the island has no cemetery, which Weber has long thought of as a critical omission.

“Prudence Island is a tight community; if you love it, it really is home,” she said. Lots of people who love Rhode Island and Narragansett Bay would like to use the island or its nearby waters as a final resting place for their body or ashes.

For years, Weber had no luck persuading a local conservation group to solve the lack of a cemetery. In 2018, she said, five lots forming a 3.3-acre plot of wooded land on the island came up for sale. She bought it and began taming the property, adding mulch and a modest shed for gatherings and storage, and removing nuisance plants. It began doing business as a burial ground in 2019.

The memorial park has mulched paths, a few wooden benches, and a gazebo. There are no grave markers apart from fieldstones that lie flat on the ground. Weber owns a Victoria-era caisson for transporting caskets or shrouded bodies. Since 2019, the memorial park has hosted two burials and Weber has pre-sold 30 plots. She said interest in the property is coming from both Rhode Islanders and out-of-state people. All are welcome.

Weber calls the practices of contemporary traditional funerals “grossly wasteful,” but she also loves the idea of green funerals because they are “participatory. It is a healthier way for most people.”

At one of the burials there, she said, kids in the family decorated the cardboard casket with photos and flowers. Another group took an active role in filling the grave.

Weber believes green funerals will become more popular in the future. “There is a kind of cultural denial of the reality that bodies decompose when we die,” she said. “We have managed to pretend it doesn’t happen. But in a green burial, over time, people will give back to the Earth by letting the nutrients in their bodies be taken up by the trees and shrubs.”

Swan Point Cemetery, in Providence, opened a green burial section called The Ellipse in 2019, based on requests from families, said Anthony Hollingshead, president of Swan Point Cemetery. The Ellipse has 148 grave spaces, and half of them have been sold. The area is grassy, bordered by large, old rhododendrons. There are no memorials on the graves; instead, names, along with birth and death dates, are inscribed on three ledger stones in the center of the space.

People like the green option because it feels “like a return to nature,” Hollingshead said. “Families don’t strongly oppose the traditional burial, but they like the wicker caskets. They like the idea of a peaceful area under a tree. They like that this is plain, not ornate. They seem to be people who have a bit more concern for the environment. This is a very popular option.”

Past to Present to Past

Green burials have been gaining popularity for about two decades, but they actually resurrect the practices of an earlier America, say, before the Civil War. Jimmy Olson, a funeral director in Sheboygen, Wis., and spokesperson for the National Funeral Directors Association, traced the history of contemporary funeral practices.

In pre-1860 America, Olson said, most people lived on farms and in towns. Burial grounds were on the family farm property or in a graveyard located cheek-to-cheek with the local church. “People lived at the homestead; everyone walked wherever they went; and people died at home,” Olson said. At the time of death, family members prepared the body, held services at home or in a local church, dug the grave, and buried their loved ones.

During the Civil War, people wanted their men’s and boys’ bodies returned from the battlefield for burial. This was the start of embalming, in which blood and fluids are drained from the body and replaced with chemicals that prolong preservation. Early embalming fluids contained arsenic, a poison that, to this day, still leaches from some Civil War-era graveyards. (Funeral professionals don’t miss any chance to point out that Abraham Lincoln was the first president to be embalmed.)

Today, embalming is used to slow down decomposition and to restore a fuller and healthier appearance to the dead person’s face during funeral services. A side effect is preservation of the body, but funeral home directors quickly note that decomposition will inevitably happen.

Around the time of World War I, Olson continued, as the country became more industrialized, cemeteries turned to backhoes and similar heavy equipment to dig graves. Old burial sites sink and create a wavy, uneven ground surface. Cemetery managers — not legislators — began requiring underground cement vaults to enclose the casket to prevent sinking of the ground.

Flat and level ground made possible by vaults allows backhoes, mowers, and trucks to move unhindered through conventional — sometimes called “lawn” — cemeteries. That is the vaults’ only purpose. Funeral professionals always note that cement vaults will eventually fail and allow water and fluids to move in and out.

The cement used in vaults is a major polluter during every stage, from manufacturing to transportation. Vaults can weigh 2,000 to 23,000 pounds. A 2019 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics reported that the cement in a single vault releases 1,860 pounds of carbon dioxide into the environment. The Green Burial Council says that, in the United States, vault manufacturing requires production of 1.6 million tons of reinforced concrete annually.

The result of all of this: underground pollution and waste of resources. And, for some people, funerals that feel like a production, not a quiet celebration of a life.

Olson said up to the past decade or so, as green burials have become more recognized and available, the funeral industry offered only two stark and not fully satisfying options: a full funeral or cremation. The latter has become more popular, rising to about 55% to 65% of all end-of-life methods, according to Olson and other professionals. He said cremation flipped to a majority choice about five years ago.

Cremation, which one funeral director called the “McDonald’s” of funerals, is dirty. Natural gas is used to burn the body, and 250 pounds of carbon are released into the air by a single cremation. Emissions also include volatile organic compounds, particulates, sulfur dioxide, and heavy metals.

Tom Olson (no relation to Olson of Wisconsin) is director of the Olson & Parente Funeral Home, in Providence. “More and more people are not going for the [conventional] funeral. Families are looking for something more meaningful, smaller, and more progressive. People looking at green burial are more educated and conscious of the environment. It is more important for them to do what feels right than to follow what their parents did.”

He said Olson & Parente has done “a lot” of green burials.

Mark Russell, owner of the Monhan Drabble Sherman Funeral Home in East Providence, said, “It is a philosophical way out.” He noted his company has done only a handful of green burials in the past five years, since Swan Point opened its facility.

Costs

Anyone who believes a green burial will be cheap way out will soon be disabused of that idea. An eco-friendly way of living, buying an electric vehicle, for instance, can be expensive, and that is no less true in death.

Bixby, of the Green Burial Council, offered a few price comparisons. He said a conventional funeral costs about $12,000. A cremation costs about $3,000 to $3,500. A green burial costs about $4,500 to $6,000. Of course, these figures vary somewhat by region. Other funeral directors generally agreed with Bixby’s estimates.

In a green burial, the major reductions in cost are the embalming, the cement vault, and the exotic-wood casket; eco-friendly caskets in pine or commercially made shrouds also may cost in the hundreds of dollars. Funeral homes are used in almost all green burials.

Prudence Memorial Park charges $1,500 for burial rights and $500 to open and close the grave. These charges are for graves that may be reopened and reused after 60 years. Perpetual rights, for grave spaces that will never be reused, is $2,250 for burial rights. These charges do not include funeral home services.

At Swan Point, in Providence, a space for a basic conventional double-depth burial — that is, for two caskets, one on top of the other, presumable for married couples — costs $4,300, according to Hollingshead. A green burial costs $4,825. The higher charge is because green plots, in the absence of cement vaults, may settle. They may require more inspections, and more filling and reseeding.

(The gradual settling of graves is the reason that you see, say, in movies of the Old West, a curved mound of dirt piled above the grave. The mounded dirt is taken from the grave, and it will eventually sink into the ground.)

A green burial at Arnold Mills Cemetery, in Cumberland, costs $2,100, said cemetery association president Karl Ikerman. One factor is that a green burial plot requires 100 square feet, under Green Burial Council regulation, which is three times the normal space.

“Funeral homes have no need to feel competition from green burials,” Bixby said. “Green will never grow unless the funeral industry is included. People are asking for this.”

Hollingshead, of Swan Point, agreed. “We want whatever makes the family comfortable.”

The Power Of Dirt

The Green Burial Council was formed in 2005, largely to educate people about end-of-life choices. The council gets plenty of questions about whether bodies in the ground will pollute soil or water resources.

In a green burial the grave is 3½ to 4 feet deep, allowing an 18- to 24-inch “smell barrier” of soil between the body and the surface. This depth allows optimal decomposition. In fact, in such a burial, soil is removed and replaced into the grave in specific layers, allowing layers to return to where they started, including the placement of plant-nourishing topsoil on top.

The council assures questioners that animals cannot smell or be attracted to bodies underneath 24 inches of soil.

Asked if bodies can contaminate groundwater in the absence of embalming, a heavy casket, and vault, the council states: “With burial 3½ deep, there is no danger of contamination of potable water that is found about 75 feet below the surface. Mandatory setbacks from known water sources also ensure that surface water is not at risk.”

The council emphasized, “soil is the best natural filter there is, binding organic compounds and making them unable to travel. Microorganisms in the soil break down any chemical compounds that remain in the body.”

A closing comment is reserved for the writer Mark Twain, from an 1879 essay in which he defiantly confesses his various misdeeds: “The rumor that I buried a dead aunt under my grapevine was correct. The vine needed fertilizing, my aunt had to be buried, and I dedicated her to this high purpose.”

Mary Lhowe is an ecoRI News contributor.

Prudence Island Light, with the Mt. Hope Bridge in the background

— Photo by Juni0r75

‘Desire and remains’

Sand dunes on Plum Island, on Massachusetts’s North Shore.

“Long waves of form, and what if under a sandhill

Socrates finds a bird? If Plato finds a lobster claw?….

And the sand — the sand is a flatbed of desire and remains.’’

— From “A Path among the Dunes,’’ by Marvin Bell (1937-2020), American poet and teacher

Climbing Moosilauke: Pride goeth before the fall

On the mountain: From left, college classmates Win Rockwell, Josh Fitzhugh, Chris Buschmann and Bob Harrington.

— Photo by Jane Andrews

Truth be told, I prefer paddling to hiking, and one thing I’ve learned from the former is that sometimes it’s good to go with the flow. So when two classmates from my Dartmouth College days invited me to join them at our 52th reunion (the big 50th, in 2020, was cancelled because of COVID) and hike up to the top of Moosilauke Mountain, in New Hampshire, I said sure, count me in.

I had another, nostalgic reason for going besides friendship and bravado. Thirty three years ago, when my father was 75, he hiked up and down Moosilauke with a little help from his two sons. Both my father and my older brother were also Dartmouth graduates. “If he could do it, so can I,” went the message in my mind. The fact that, at 74, I was a year younger compensated in my mind for the other fact: I have early-stage Parkinson’s disease. (Symptons of Parkinson’s include tremor and instability.)

Now Moosilauke, elevation 4,803 feet, is sometimes called Dartmouth’s Mountain,” partly because the college owns quite a bit of the land surrounding the peak, partly because it used to hold ski races down its flank in the 1920s and 1930s, and partly because it has a timbered lodge at its base that welcomes students, faculty, alumni and sometimes even celebrities alike into what for many is iconic about Dartmouth: its connection to the wilderness of northern New Hampshire. Recently, the lodge has been extensively rebuilt using massive timbers, and, of course, New Hampshire granite.

I met my classmates, Win Rockwell and Bob Harrington, and Bob’s partner, Jane Andrews, at a park-n-ride near my home in Vermont at 7 A.M. and we drove over to the base lodge, arriving at 9.

It was a warm June day, with the sky almost cloudless. I had grabbed a coffee and roll for breakfast on our way, and the lodge had packed us a bag lunch consisting of cheese, tomato, bread, peanut butter and jelly sandwichs and brownies. I had two 8-ounce water bottles. In my knapsack I carried warmer clothing for the top in case I needed it. (In my father’s climb, one obstacle was snow at the top. The temperature in the White Mountains can sometimes rapidly drop 50 degrees at the summits, with wind gusts of 40 miles an hour or more.) It was warm enough for shorts. I had climbing boots but very light socks, which were intended to give my toes more room. (I like the boots but sometimes my toes banged into the leather.) I suffer from peripheral neuropathy in both feet, but the tingling I usually experience had not previously bothered me walking.

After discussion amongst my friends, I also decided to take a pair of bamboo cross-county ski poles to assist in balance and motion if necessary. Many people now hike with poles, some extendable, regardless of age.

We left on the main trail from the lodge at 10 a.m. The straightest route to the summit (the route we took) is about 3.5 miles up the Gorge Brook trail, with an elevation climb of 2,933 feet. Hikers in good condition traveling in dry conditions should be able to make it to the peak and back in about 3 hours, with a 20-minute break at the summit.

As we started our hike, I tried to recall my last outing three and a half decades ago. The trail seemed a bit rockier this time and I didn’t recall hearing the water tumble over rocks in the nearby brook. At first all seemed fine. Gradually, however, I felt more and more as though I was walking in the brook, not because the going was wet but because I was having to step rock to rock rather than walk on soil or gravel. In places the soil had eroded so much that the college (through the Dartmouth Outing Club, I believe) had placed large flat stones in a kind of stairway, with the rises varying from 6 inches to a foot and a half.

We stopped after about a mile to eat some of our provisions and enjoy the view to the north. I felt fine if a bit tired. We were passed periodically by younger hikers, some alone and many with dogs. At about the two-mile mark I began to ask hikers coming down the time to the summit. “Oh, it’s not too far,” was a common response.

At about 2.5 miles in I started having balance issues. Now, though I have Parkinson’s, I had not had before one of the common symptoms, instability. Mostly I have a slight tremor in my right hand and some slurring of speech. I tend to walk slowly with a forward hunch. I’m a former soccer fullback, downhill skier and amateur logger, and I’m still in decent shape. But here on Moosilauke, I found myself losing my balance to the rear. In short, I kept falling backwards! My poles helped a bit, but sometimes I found myself having to take two steps back. Then, in one fall, I slammed my left temple hard into a rock in part of the trail that was mostly boulders.

Now you’ve done it, I said to myself, fearing a subdural hematoma, swelling, loss of consciousness and death. Luckily, my friends came to my rescue, checked my vision and saw no bleeding. I had no headache. We continued, but more slowly, with one classmate walking just behind me. I thought of the old Dartmouth song that refers to its graduates having the granite of New Hampshire “in our muscles and our brains.” It’s a good thing, I thought.

At about the two-mile point of the hike, there is a false summit. You are above the tree line and the view opens up. Solid granite outcroppings replace the big boulders we had been walking on. Thinking that we were close to the top, I exulted until, looking again, I saw another rise ahead. “Is that where we have to go?” I asked wearily. “’Fraid so,” said Win, whose father had hiked all over these mountains as a student at Dartmouth in the 30s. “I think I better turn back,” I responded to the general agreement of my team. It was about 2:30 p.m.

Bob agreed to monitor me down the trail, although that meant he lost his opportunity to reach the summit. The other two, Win and Jane, seemed very fresh and expressed their desire to push on and catch up to us on the way down.

Bob Harrington and Jane Andrews made it to the top.

Now most hikers learn quickly that “down” does not necessarily mean “easier.” While I need to lift 219 pounds (my weight) with each step going up, I need to stop the inertia force of 219 pounds going down. In addition, at least for me, on rocky terrain I fear falling downhill more than I fear falling uphill. Gravity will aggravate the momentum falling downhill, I reason.

For me and Bob, then, the trip to the lodge became slower and slower. My legs were weakening and I was becoming very careful about each step. The routine was the same: Get yourself steady, examine the terrain ahead, identify a landing spot, plant poles, transfer weight to the downhill foot in a kind of leap of faith, say a small prayer when you succeeded, repeat.

At about 4 p.m., Jane and Win caught up with us on their downhill journey. Bob and I were only about a mile into our descent. We were stopping every 100 yards or so to let me rest. The decision was made to send Bob and Jane back to the lodge for possible assistance while Win would try to assist me. (We were joined about then by another Dartmouth graduate and his wife, Rick and Lucie Bourdon, who altered their plans to help both physically and emotionally in what was increasingly becoming an ordeal for all of us.)

It’s worth noting here a word about Moosilauke. When the mountain was first developed, in the early 1900’s, a cabin was built at the peak for overnight lodging. (It burned to the ground in 1942.) To help construct and provision that cabin, a dirt road was constructed to the peak. With the destruction of the cabin, that road got less and less traffic and is now mostly overgrown. You can hike on that road, but it is not much easier than the other trails. You also need to be at the peak or the base lodge to access that “carriage road,” so we had no choice but to go down the way we had come up.

In short, once you climb up on Moosilauke, the only way down is to walk, or be carried. Despite my wish as expressed during the descent, there is no zip line or chair lift for exhausted duffers like me. I stopped and sat on rocks or tree stumps with increasing frequency. (“Josh you are doing fine,” Lucie would say. “You have a team behind you!”) At one point Win and I decided that it was better to bushwack off the trail than struggle rock by rock while on it. At least then when I fell the branches and moss- covered rocks I hit were softer than the rocks in the trail, and saplings sometimes provided handholds to brake my descent.

Thankfully, this was one of the longest days of the year and the weather was clear and mild. Nevertheless, by 7 p.m. it was getting dark and we were still a half mile from the lodge. There was still a steep rocky trail ahead. I stumbled off the trail near the brook that I had heard on the way up. Losing my balance I fell, and could not get up. The muscles in my legs were too tired. After Win (who is probably 60 pounds lighter than me) dragged me to a soft spot off the trail, I remember saying, “You guys will have to figure out what to do. I’m done.” I stretched out, closed my eyes and tried to sleep.

By this point, Lucie and Rick had gone on ahead to report my condition and check on help. It began to rain and Win loaned me a parka. It wasn’t expected to be a cold night, and so I said, “Just get me a tarp and my sleeping bag at the lodge. I’ll just spend the night here!” “No way,’’ said Win.

It was dark by the time that two Dartmouth students, Alex Wells ’22 and Jules Reed ’23, arrived. Both were working in the kitchen at the lodge, but had hiking experience, and they had head-mounted flashlights. After they lifted me by my shoulders, I slung one arm over each of their necks. Then, like some six-legged decrepit spider, or a drunken Rockettes threesome, we inched our day down the trail with each of us simultaneously deciding which rock to step upon. When either of them tired, Win took their place.

Forty minutes later we could see the lights from the lodge, and closer still, the lights from the cabin I was sleeping in. No dinner for me, I told them, just get me to my bunk and bring me a bottle of wine. They did and I collapsed in bed, thankful to have made it down and for the help that made that possible. The next morning I learned that Win had used the lodge’s one telephone (there is no cell service at Moosilauke) to call my wife and leave a message. “First of all, let me tell you that Josh is okay,” he had begun.

Postscript

Decades ago, while in high school, I would occasionally quote Socrates, the Greek philosopher, who had said, “the unexamined life is not worth living.” When I have encountered traumatic moments in my life, I have sought to learn from the experience. This was no different. What caused my collapse on the mountain? Should I ever hope to hike again? Could others learn from my ordeal?

Looking back, I clearly should have prepared more for this hike, by taking some shorter hikes with lesser elevations, by having boots that fit better, by using proper hiking poles rather than old, bamboo cross-country poles, and by having a better breakfast and more robust lunch. I should have taken more water and less cold-weather gear in my backpack.

Maybe with Parkinson’s I should not have gone at all. The stress of the climb certainly exacerbated my instability, and my condition put a big burden on my friends. For them, it turned what could have been a delightful summer hike into a memorable, anxious ordeal. Of course, it also reaffirmed the value of friends and the Dartmouth “family.” I would have stayed on that mountain were it not for my saviors.

I do think that the college shares some responsibility for the episode. While I did not inquire, there were no notices that I saw of trail conditions or warnings that the Gorge Brook trail might be unsuitable for people over the age of 70 or suffering from ambulatory instability. Stating the obvious perhaps would be a caution that climbing the mountain is not the hardest challenge; you still have to get down!

In the years since I last climbed Moosilauke, with my father and brother, the trail to the summit has deteriorated greatly from the flow of rain and melting snow. Rather than relocating the trail, the college has sought to remedy it by making a staircase in many locations This works for those with strong knees, hips and ankles but for those like me, hundreds of 12-inch risers exhaust quite a bit of energy both going up and coming down. A better solution to trail washout might be to deposit 1-or-2-inch crushed stone in the interstices between the larger boulders to create a kind of stone path to the summit. This would be difficult and expensive and certainly change the nature of the hike, but it also would improve accessibility and safety, in my humble opinion. If this is feasible I’d be happy to contribute. I have a debt to repay.

From left, Josh Fitzhugh and Good Samaritans Jules Reed and Alex Wells with me after my misadventure.

John H. (“Josh”) Fitzhugh is a writer, former insurance-company CEO, former newspaper editor and publisher and former legal counsel to two Vermont governors. He lives in Vermont, Florida and on Cape Cod.

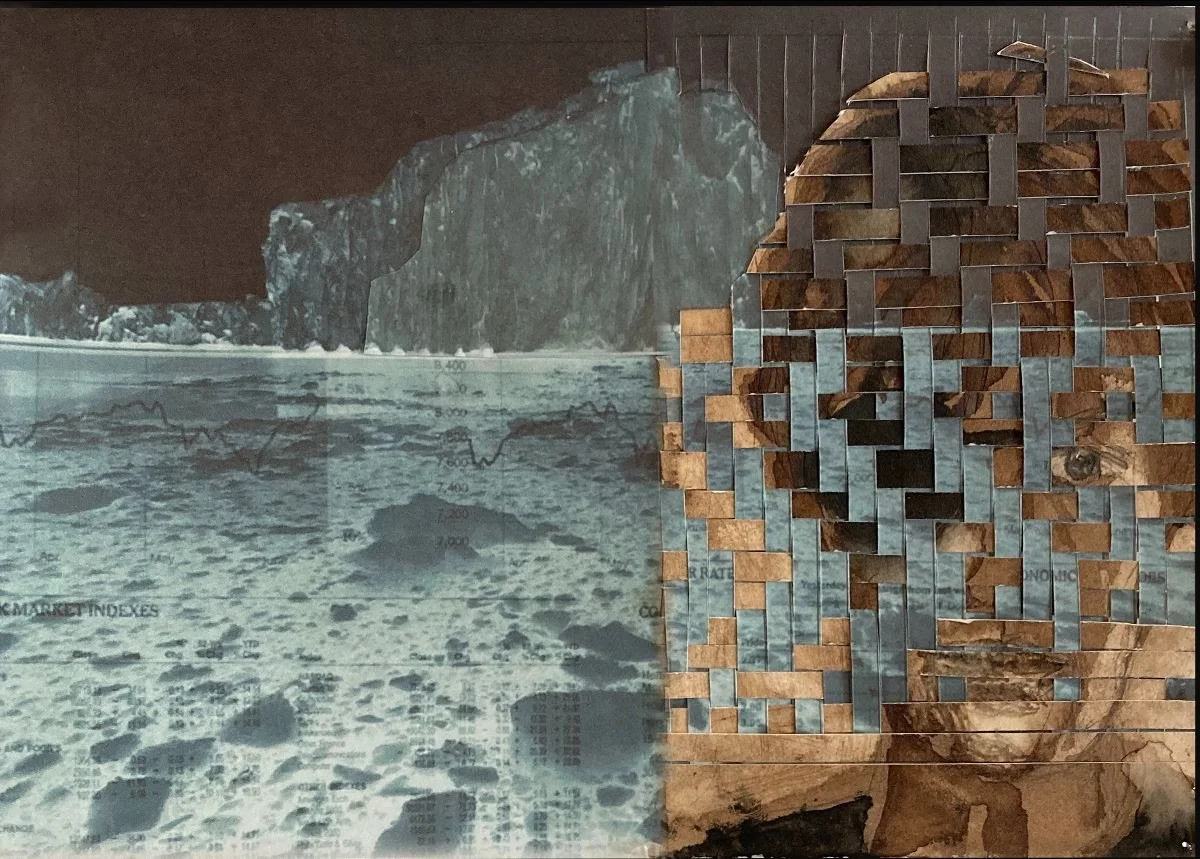

Self-portraits and world portraits

“Portrait 1 (ink on paper, digital print), by Ellen Driscioll, in her show “Splinter,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, Oct. 5-Oct. 30.

The gallery says: “‘Splinter’ is an intimate and probing array of self-portraits that create intricate matrices, interlacing her inner life with maps, charts, and images of an outer world undergoing constant change. While recovering from a rare brain tumor that initially rendered her unable to walk or see and prompted visual hallucinations, Driscoll began to draw herself in the starkest and most self-revealing manner. Over time, Driscoll began to interweave the self-portraits with images of melting glaciers, oil refineries, forest thickets, and birds, reflecting the artist’s long artistic preoccupation with global warming and environmental degradation. In each image, Driscoll’s face indelibly captures a vivid sense of a world and self, both intertwined and slipping away.”

David Warsh: The mid-terms, ‘national conservatism’, U.K. confusion, Anglo-Saxon invasion

Ohio Democratic Congressman and U.S. Senate candidate Tim Ryan

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The way I see it, the United States and its NATO allies goaded Vladimir Putin into a war that Russia cannot hope to win and which Putin is determined not to lose. What will happen next? The U.S. mid-term congressional elections, that’s what.

Interesting election campaigns are unfolding all across the nation. I take everything that Republican Party strategist Karl Rove says with a grain of salt, but suspect he is correct when he predicts the GOP will pick up around 20 seats in the House in November, enough to give Trumpist Republicans a slender majority there for the next two years. The Democrats likely will control the Senate, setting the stage for the 2024 presidential election.

To my mind, the most interesting contest in the country is the Senate election involving 10--term Congressman Tim Ryan and Hillbilly Elegy author J. D. Vance, a lawyer and venture capitalist. That’s because, if Ryan soundly defeats Vance, he’s got a good shot at becoming the Democratic presidential nominee in 2024. Ryan and Vance have agreed to two debates, Oct. 10 and 17.

By ow, it goes practically without saying that President Joe Biden will not run for re-election on the eve of turning 82. Ryan, who will be 51 in 2024, challenged House Speaker’s Nancy Pelosi’s leadership of the Democratic Party party in 2016, and sought the party’s presidential nomination in 2020.

A demonstrated command of the battleground states of the Old Northwest – Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin – would make Ryan a strong contender against Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, the likely Republican nominee.

It was a turbulent week. Having proclaimed Russia’s annexation of four Ukrainian regions, Putin delivered what Robyn Dixon, Moscow bureau of The Washington Post, described as “likely the most consequential” of his 23 years in office. But rather than a clarion call to restore Russian greatness as he clearly intended,” she wrote, “the address seemed the bluster and filibuster of a leader struggling to recover his grip — on his war, and his country.”

A starling miscalculation by Britain’s new Conservative Party government threatened to destabilize global financial markets. And the costs of gradual global warming continue to make themselves clear.

In the midst of all this, an old friend called my attention to two essays that seemed to take antithetical views of the prospects. The first, “How Europe Became So Rich’’, by the distinguished economic historian Joel Mokyr,

Many scholars now believe, however, that in the long run the benefits of competing states might have been larger than the costs. In particular, the existence of multiple competing states encouraged scientific and technological innovation…. [T]he ‘states system’ constrained the ability of political and religious authorities to control intellectual innovation. If conservative rulers clamped down on heretical and subversive (that is, original and creative) thought, their smartest citizens would just go elsewhere (as many of them, indeed, did).

Mokyr concluded, “Far from all the low-hanging technological fruits having been picked, the best is still to come.”

The second, “Seven Years of Trump Has the GOP taking the Long View’’, by long-time newspaper columnist Thomas Edsall, cites the success of Viktor Orban in governing Hungry, and then examines various signs of the vulnerability of the liberal state in America. These include the durability of the Trump base, and an incipient “National Conservatism” project, created in 2019 by the Edmund Burke Foundation, since joined by an array of scholars and writers associated with such institutions, magazines and think tanks as the Claremont Institute, Hillsdale College, the Hoover Institution, the Federalist, the journal First Things, the Manhattan Institute, the Ethics and Public Policy Center and National Review.

What characterizes national conservatism? Commitments to the infusion of religion and traditional family values into the government sphere, Edsall says, and, perhaps especially, opposition to “woke progressivism,” Conservative Conference chairman Christopher DeMuth puts it this way: Progressives promote instability and seek “to turn the world upside down:”

[M]ayhem and misery at an open national border. Riot and murder in lawless city neighborhoods. Political indoctrination of schoolchildren. Government by executive ukase. Shortages throughout the world’s richest economy. Suppression of religion and private association. Regulation of everyday language — complete with contrived redefinitions of familiar words and ritual recantations for offenders.

All I could do in reply was to take comfort in evidence that borders have been open to chaotic traffic for a very long time, across barriers more intimidating than the Rio Grande River, resulting in successful assimilation. Science magazine (subscription required) reported last month that new archaeological evidence tends to support the traditional view of “How the Anglo-Saxons Settled England”.

An 8th Century (C.E.) history written by a monk named Bede asserted that Rome’s decline in about 400 C.E. opened the way to an invasion from the east. Tribes from what is today northwestern Germany and southern Denmark “came over into the island, and [the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes] began to increase so much, that they became terrible to the natives.”

For a time, archaeologists doubted Bede’s account, preferring to think that only a relatively small bands of warrior elites could have successfully imposed their culture on the existing population. “Roman Britain looks very different from the Anglo-Saxon period 200 years later,” one archaeologist acknowledged to Science. But DNA samples from the graves of 494 people who died in England between 400 and 900 show they derived more than three-quarters of their ancestry from northern Europe.

The results address a long-standing debate about whether past cultural change signals new people moving in or a largely unchanged population adopting new technologies or beliefs. With the Anglo-Saxons, the data point strongly to migration, says University of Cambridge archaeologist Catherine Hills, who was not part of the research. The new data suggest “significant movement into the British Isles … taking us back to a fairly traditional picture of what’s going on.”

That doesn’t mean that the migration was especially turbulent, as when the Vikings began raiding a few centuries later, leaving relatively few genetic traces behind. Language changed relatively quickly after the Anglo-Saxons began arriving, a sign that people were talking, not fighting. Integration and intermarriage persisted for centuries. Indeed, archaeologists discovered “one high status woman in her 20s with mixed ancestry was laid to rest near modern Cambridge under a prominent mound with silvered jewelry, amber beads, and a whole cow.” That suggests more complexity than simple conquest, one archaeologist told Science.

Same as it ever was, in other words – all but the cow.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals. com

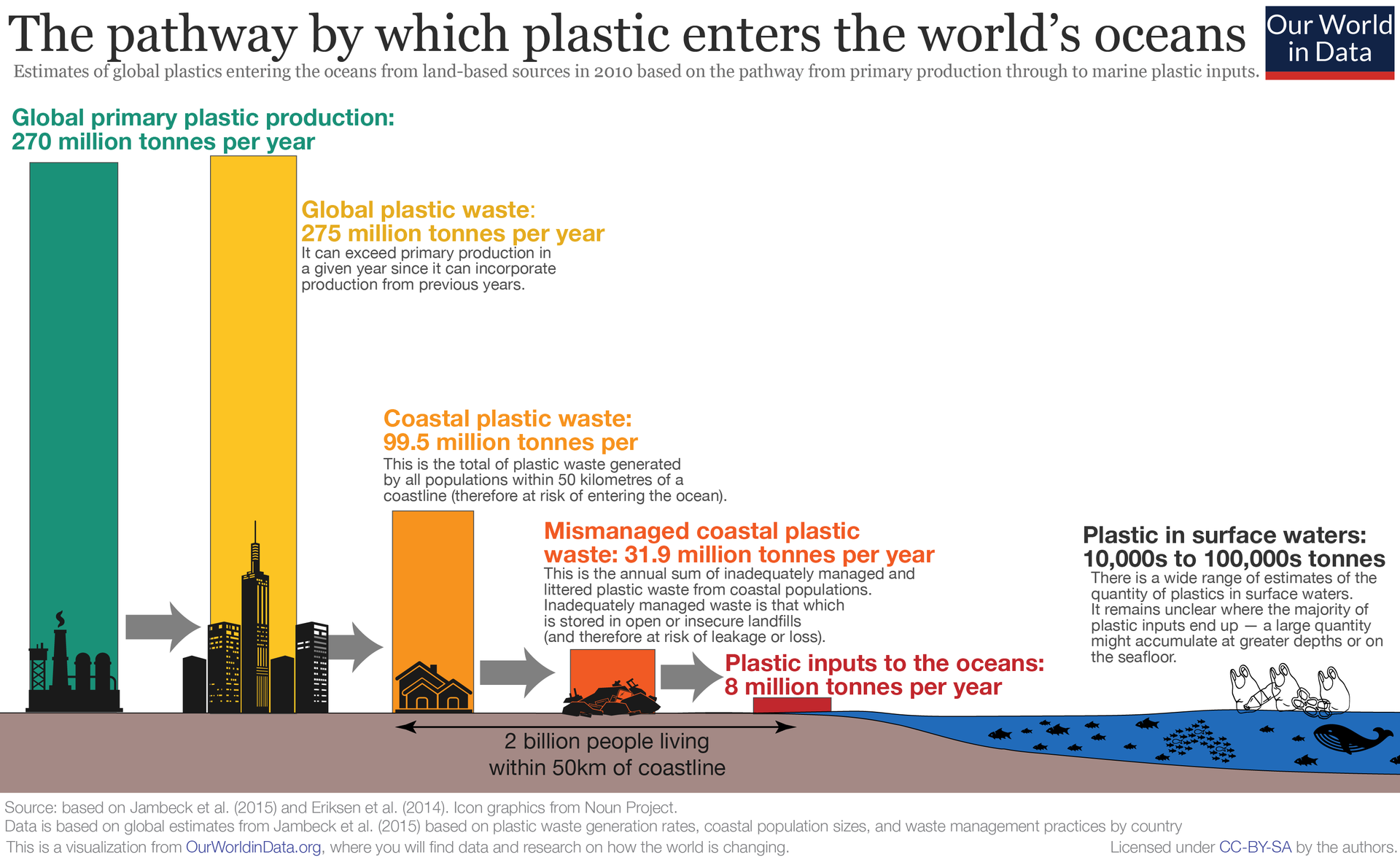

Pandemic of plastic pollution

Polystyrene foam beads on a beach.

-- Photo by G.Mannaerts

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Plastic pollution very seriously threatens our ecosystems.

Thus it was good to learn that the University of Rhode Island has won a $1 million contract to research the effects of this growing and still inadequately understood pollution in the water and on land that kills wild animals and harms human health. To get some sense of how serious this problem has become, just walk on a beach.

The reputation of URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography is the major reason the university won this contract.

Hit this link for an article about international plastic pollution of the ocean.