No they don’t

Preparing johnnycakes, which are made with corn meal.

— Photo by Douglas Perkins

“A true Rhode Island Yankee will have jonny-cakes with all three meals: with bacon and eggs in the morning; with pork chops and boiled potatoes at noon; and with Yankee pot roast for supper.’’

— Donald J. Boisvert, in 500 tomato plants in the Kitchen (2001)

Kenyon Corn Meal Co., a grist mill in Usquepaug, R.I. The building shown was built in 1886, and the enterprise dates from 1696.

‘Decomposition and rebirth’

“Last Steps,” by David Shaw, in Ridgefield, Conn., in the The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum’s Main Street Sculpture program through next April 23.

The museum says:

“Shaw’s recent work explores the indistinct boundaries that separate nature, technology, and consciousness. ‘Last Steps,’ which takes the form of a step ladder, is in a process of decomposition as well as rebirth, with gleams of spectral light appearing in gaps in the moss-like growth that has enveloped it, suggesting an alternate reality or a regenerative possibility lurking beneath the surface.”

“The artist’s use of the ladder form—but with missing rungs—speaks of the challenges we face as a civilization as we try to heal what has been lost.’’

Shaw says: “As we begin to embrace our responsibilities to the natural world, ‘Last Steps’ is both an image of our frustrated, unattainable, and perhaps misguided desire for progress, and a symbol of hope that the world wants to rebuild, that life wants to continue.”

Ridgefield’s Peter Parley Schoolhouse (c. 1750), also known as the Little Red Schoolhouse or the West Lane Schoolhouse, is a one-room schoolhouse in use by the town until 1913. The site and grounds are maintained by the Ridgefield Garden Club. The building is open certain Sundays and displays the desks, slates, and books the children used.

Chris Powell: Woke schools hate being public

Southington (Conn.) High School’s eerie logo.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

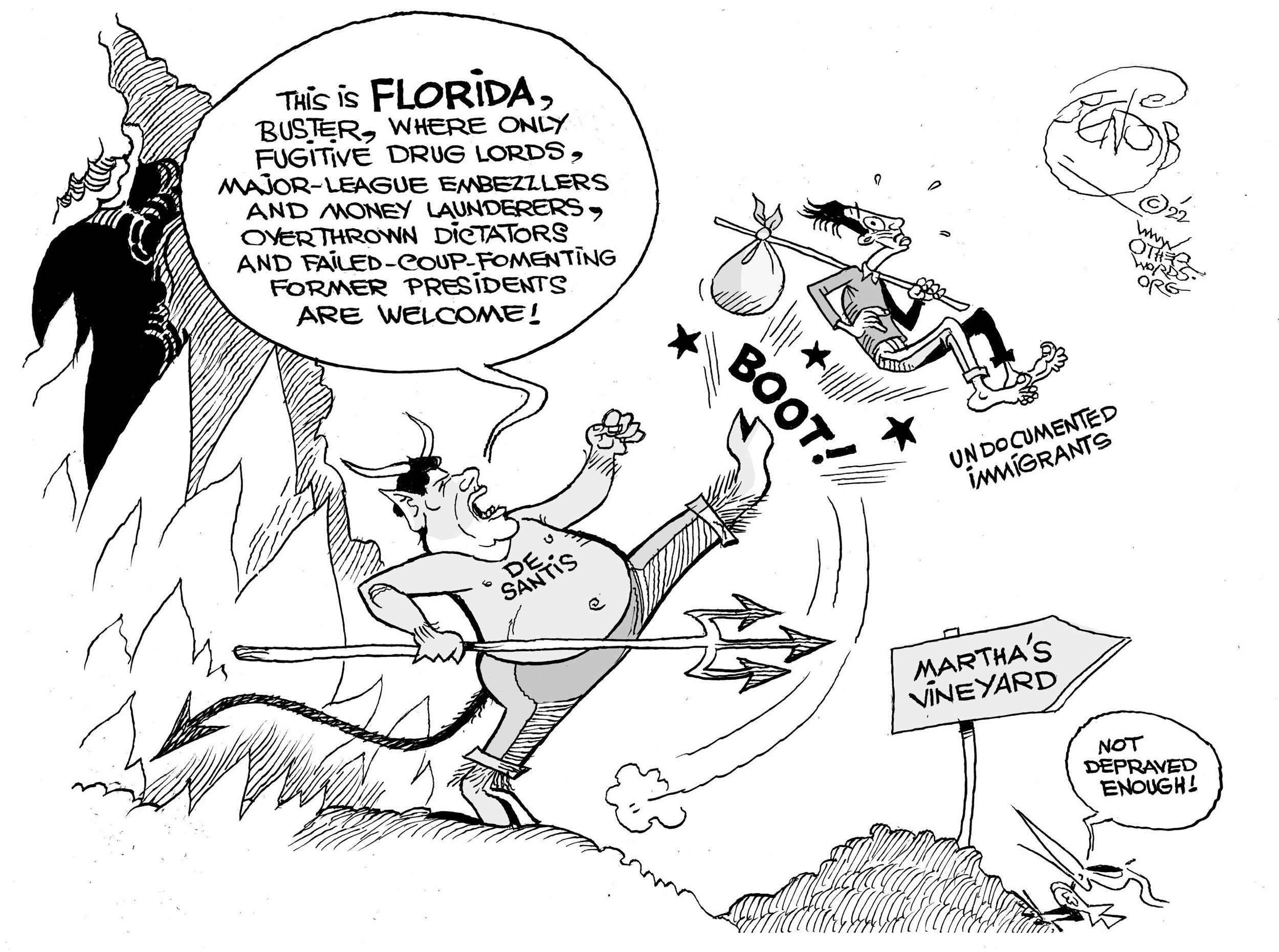

Maybe that assistant principal in Greenwich who was recently caught admitting that he hires only young liberals as teachers, the better to propagandize students into voting Democratic, wasn't such an outlier. The more recent incident at Southington High School, where an English teacher was caught inflicting political propaganda on students, suggests that Connecticut may actually be the center of the campaign to dump education for indoctrination.

The teacher distributed to students a packet titled "Vocabulary for Conversations about Race, Gender, Equality and Inclusivity." It contained a glossary of terms involving transgenderism and racism, topics with which public schools are increasingly obsessed to the detriment of education. The glossary had no relation to material being taught in the teacher's English classes but supposedly was meant to help if discussion ever turned to the glossary's subjects.

Another section of the packet revealed that its objective indeed was to turn discussion to those subjects for indoctrination purposes. It said: "You can know in your heart that you don't hate anyone but still contribute to their oppression. No individual is personally responsible for what white people have done or the historical decisions of the American government, but you are responsible for whether you are upholding the systems that elevate white people over people of color."

That is: You kids may be oppressors too without even knowing it -- yet.

While Southington School Superintendent Steven Madancy told a Board of Education meeting that he supports his teachers, in an open letter to the town he admitted that the English teacher had gone too far. "As a result of our comprehensive review," the superintendent wrote, "the teacher now realizes that the sources utilized to develop these supplemental materials may not have been neutral in nature and recognizes the bias and controversial statements that some took issue with."

So the teacher had been counseled not to do stuff like this again, which ordinarily might be enough. But instead things got worse.

The school board's chairwoman, Colleen Clark, chided those who complained about the propagandizing. "I resent that a personnel matter regarding one of our teachers and our schools has been turned into a political platform by those who have noneducational agendas," Clark said.

But those who complained about the English teacher's manifesto weren't the ones injecting politics into the schools; that was done by the teacher. (Since this is "public" education, despite the misconduct involved, the teacher has not been identified.)

Besides, since nearly everything in public education is to some degree a personnel matter, democracy inevitably makes public education political.

The situation got still worse with an open letter to the Southington board from 60 members of the faculty of Southern Connecticut State University, who called the board's review of the teacher's conduct "a politically motivated attack on free speech."

But the teacher's freedom of speech wasn't attacked. The teacher was faulted for commandeering the school curriculum, which is for the school administration, the school board, and, ultimately, the public to determine.

That is exactly what the Southern professors meant to deny. They continued: "We strongly support parental rights in the home. But few parents are experts in education. … Parents … should not determine which texts are read and what language is introduced in order to make sense of those texts.

“To permit parents -- or students -- to object to what they perceive as ‘divisive' texts is to descend down the slippery slope of allowing a relatively small but vocal group of parents and students to circumscribe and dictate the nature of public education.”

That is, the public has no right to review "public" education, which should be left to those who suppose themselves to be experts.

Instantly the Southern professors had turned from purported defenders of free speech to resentful opponents. For the critics of the teacher's manifesto didn't "circumscribe and dictate the nature of public education." They exercised free speech in pursuit of their equally constitutional right to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Once again those who dominate "public" education in Connecticut have revealed that they don't think it should be public at all.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer in Manchester. CPowell@JournalInquirer.com)

The Southington Congregational Church.

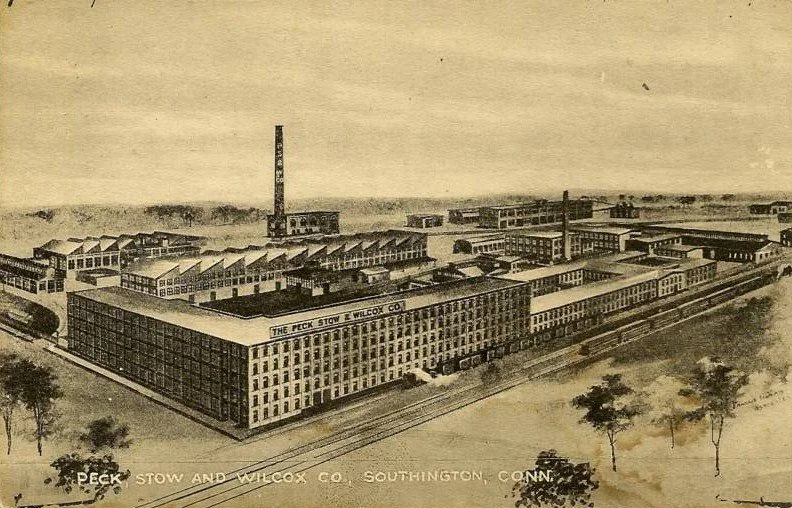

Long-gone tool factory in 1910.

Commuters

— Photo by Schnäggli

“As if a cast of grain leapt back to the hand,

A landscapeful of small black birds, intent

On the far south, convene at some command

At once in the middle of the air, at once are gone….’’’’

— From “An Event,’’ by Richard Wilbur (1921-2017), a two-time Pulitzer Prize winning poet and teacher who spent most of his life in New England.

Fun house

“Time for You and Joy to Get Acquainted” (wooden armature, fabric, polyfoam), by JooYoung Choi, in the show “State of the Art,’’ at the Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, N.H., Oct. 20-Feb. 12.

This piece of art is from the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Ark.

Huge buildings in Manchester along the Merrimack River that comprised the Amoskeag Manufacturing Co. complex. The company grew in the 19th Century into the largest cotton-textile facility in the world.

At least it’s ‘systematic’

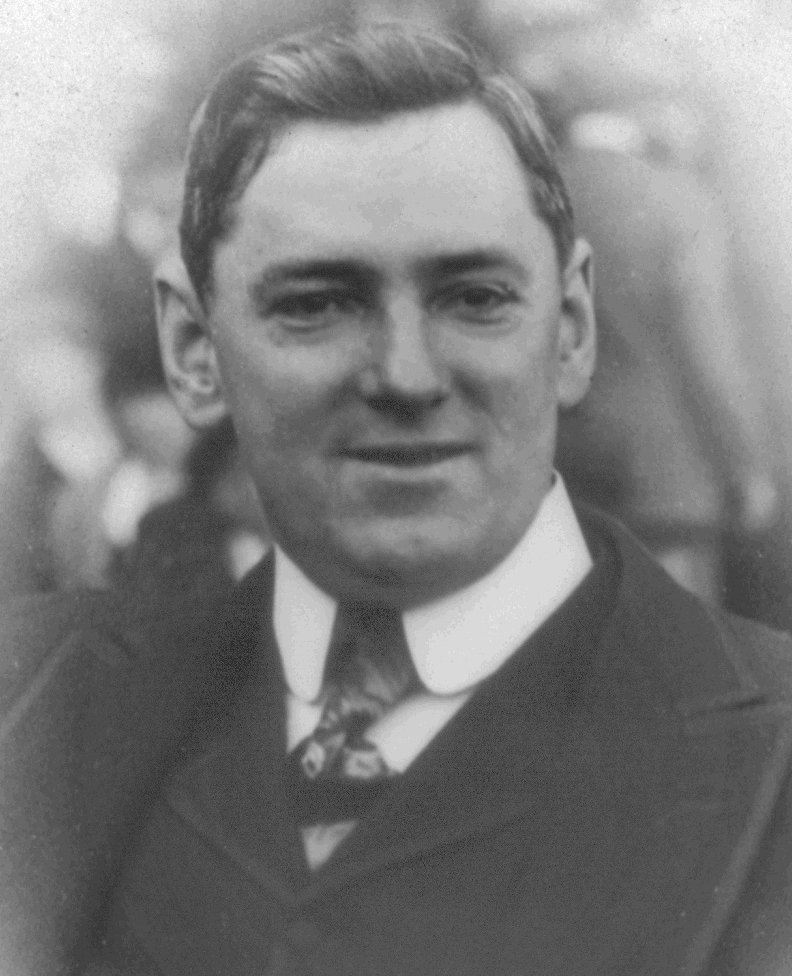

The corrupt and highly entertaining James Michael Curley (1874-1958), who in his terms as Boston’s mayor skillfully appealed to the resentments of city’s Irish-American residents about the “Boston Brahmin” WASP elite. He was the basis of Edwin’s O’Connor’s great novel The Last Hurrah.

Editor’s note: My paternal grandfather first met Curley in 1930, when they had a conversation of about 10 minutes. He next encountered him in 1949. Curley asked after my grandmother and her two children by name and other related family stuff. Like most great pols, he had a capacious memory for personal information about current and potential voters.

“Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds, and Massachusetts politics had been as harsh as the climate. The chief charm of New England was harshness of contrasts and extremes of sensibility —a cold that froze the blood, and a heat that boiled it —so that the. pleasure of hating—oneself if no better victim offered —was not its rarest amusement; but the charm was a true and natural child of the soil, not a cultivated weed of the ancients. The violence of the contrast was real and made the strongest motive of education. The double exterior nature gave life its relative values. Winter and summer, cold and heat, town and country, force and freedom, marked two modes of life and thought, balanced like lobes of the brain. Town was winter confinement, school, rule, discipline; straight, gloomy streets, piled with six feet of snow in the middle; frosts that made the snow sing under wheels or runners; thaws when the streets became dangerous to cross; society of uncles, aunts and cousins who expected children to behave themselves, and who were not always gratified; above all else, winter represented the desire to escape and go free. Town was restraint, law, unity. Country, only seven miles away, was liberty, diversity, outlawry, the endless delight of mere sense impressions given by nature for nothing, and breathed by boys without knowing it.’’

Henry Adams (1838-1918), in The Education of Henry Adams (1918). He was a member of the famous Boston] area-based Adams political family that started with President John Adams.

N.E. clean-energy update

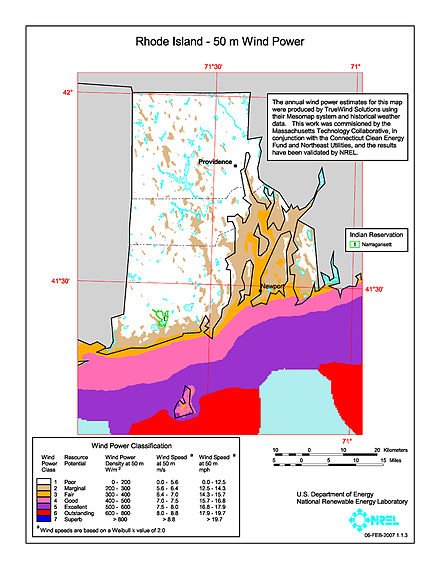

2007 U.S. Department of Energy wind resource map of Rhode Island

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I wonder how Newporters and tourists will respond to the sight on the horizon of 100 offshore wind turbines to be put up by Revolution Wind about 15 miles south of Little Compton. And there are other big offshore “wind farms’’ in the works south of New England. The Revolution Wind turbines will be the closest to Rhode Island.

There will be complaints from some folks who don’t want to look at them, even from a distance, but most people will get used to them fast, as they generally do with big new infrastructure. And many think that the giant turbines, of the sort that have long been spinning along the coasts of Europe, are beautiful. (Thank God the Europeans have been much more decisive than us in putting up wind farms, thus reducing their reliance on Russian fossil fuel, which is used to finance Putin’s mass murder and torture in Ukraine.)

Some yachtsmen will complain about the wind farms, saying that they’ll cramp their summer racing and cruising, as will some fishermen. But many of the latter may come to appreciate that wind-turbine supports act as reefs that attract fish.

In any event, I’m sure that some boat-owning entrepreneurial types will sell tickets to take tourists from Newport to see these things close up, with blades rotating to a height of 873 feet as they cleanly, if eerily, generate electricity.

xxx

Connecticut has opened its first electric-car-charging operation on its stretch of Route 95 (aka the Connecticut Turnpike), at its Madison service plaza. And more are coming.

“Seaglider’’

— Regent picture

Finally, the folks at Regent tell me that its electric “seaglider” achieved its first series of flights on Aug. 14 on Narragansett Bay, “proving its full ‘float, foil, fly’ mission—making it the first craft to take off from a controlled hydrofoil to wing-borne flight.’’

The demonstrator is a quarter-scale prototype for its 12-passenger seaglider, Viceroy.

The company calls the seaglider “a new category of electric vehicle that operates exclusively over the water, is the first-ever vehicle to successfully use three modes of maritime operation—floating, foiling and flying—marking a major step forward in maritime transportation.’’

Regent is now focusing on developing its “full-scale, 65-foot wingspan prototype, with human-carrying sea trials expected to begin in 2024.’’

Hit this link for a video. (No, Regent doesn’t pay me.)

Soft to rough

“Charlotte” (Italian marble,) by Scott Boyd, in the show “Rock Solid XXII,’’ through Oct. 29, at Studio Place Arts, Barre, Vt., in the heart of Vermont’s granite quarrying and finishing region. (Think of the Rock of Ages Corporation’s gravestone and other products.) The state is also the source of high-grade marble.

— Photo courtesy: Studio Place Arts.

The gallery says that the exhibit “showcases the work of 20 sculptors whose work in stone is able to bring out all of the qualities of the medium — from delicate flowing sculptures that turn stone into something that looks as soft as silk to rough pieces that emphasize the rugged nature of the material.’’

The entrance to the Vermont Marble Museum, in Proctor. The Green Mountain State has been a major source of marble as well as granite.

— Photo by GK tramrunner

Rock of Ages granite quarry

— Photo by Z22

Llewellyn King: Remembering a real hero in these carping times

Chuck Yeager in front of the Bell X-1, which, as with all of the aircraft assigned to him, he named “Glamorous Glennis” (or some variation thereof) after his wife.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Winston Churchill used to advise young people to read “Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations,” the oft-updated compilation of brief quotes from just about anyone who said something memorable. Of course, Churchill added more than a few of his own. He may have added more to the storehouse of aphorisms than any writer since Shakespeare.

But others have been no slouches. If you want to go back a bit, Napoleon wasn’t unquotable, and such writers as George Bernard Shaw and Oscar Wilde were prolific with wit and wisdom served up in brevity. Mark Twain was a treasury of quotable sayings all by himself. In our time, Steve Jobs made some pithy additions and Taylor Swift, in her lyrics, has some arresting and quotable lines.

The quote to me is distilled wisdom in a few words, often funny, whether it came from Dorothy Parker, Abraham Lincoln or the Beatles. A picture may be worth a thousand words, a quote believed to have been first formulated by the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, but a well-chosen aphorism is worth many more than a thousand words.

So, it is thrilling to know that Victoria Yeager, widow of Chuck Yeager, aviation’s greatest hero, has collected his sayings into a book, 101 Chuck Yeager-isms: Wit & Wisdom from America’s hero.

Yeager came from the small town of Hamlin, W. Va. Even today it has a population of just over 1,000. Being from one of West Virginia’s famous hollows, Yeager said of it, “I was born so fer up a holler, they had to pipe daylight in.”

When the town erected a statue of Yeager, he said, “There wasn’t a pigeon in Hamlin until they erected a statue of me.”

The journey began modestly with Yeager joining the U.S. Army as a private after high school and led on to his success as fighter ace with 11.5 kills – one involved another U.S. aircraft and, hence, the half -- but Victoria Yeager told me that here were more not officially recognized. He may have shot down as many as 15 German aircraft over Europe, she said.

He was shot down himself over France in 1944; Germans watched his parachute float down and went out to find him. Yeager said, “There ain’t a German in the world that can catch a West Virginian in the woods.” And they didn’t.

In an interview for White House Chronicle, on PBS, Victoria told me that Yeager always insisted that there be fun in everything, whether it was aerial fighting, flying through the sound barrier, or flying aircraft that might kill him. “You gotta have fun in life, whatever I did, I always included fun,” he said.

Yeager, Victoria said, maintained critical aircraft like the X-1, in which he broke the sound barrier, himself. That way he knew and there would be no excuses. He said, “In the end, or at the moment of truth, there are only excuses or results.”

Victoria told me that the impression given in the movie The Right Stuff of Yeager as a reckless daredevil who rode a horse up to his aircraft, took off, and broke the sound barrier was pure Hollywood. Yeager was a consultant to Tom Wolfe during the writing of his book The Right Stuff to ensure accuracy. In fact, Victoria said, it was on the ninth flight that he broke the sound barrier. It is true that the horizontal stabilizer on the plane wasn’t working, but Yeager was able to control the plane with a manual trim tab, she added.

Yeager fought in World War II because, as he saw it, it was his duty to fight, as he saw it. After being shot down he wanted to keep fighting; and when the military wanted to send him home, he appealed the decision all the way up to Dwight Eisenhower, then the supreme allied commander in Europe, and won the right to fly in combat again. He said of duty, “You’ve got a job to do, you do it, especially in the military, when I was picked to fly the X-1, it was my duty to fly it, and I did.”

Yeager’s philosophy may have been summed up in this quote, “You do what you can for as long as you can, and when you finally can’t, you do the next best thing; you back up, but you don’t give up.”

That is the spirit that kept Yeager flying for pleasure up to close to his death, at 97.

In our carping, whining, blaming times, it is a tonic to read the thoughts and something of the life of a real hero. Thank you, Victoria Yeager, for assembling this book.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Linda Gasparello

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Mobile: (202) 441-2703

Website: whchronicle.com

Providence College’s new school

Harkins Hall (1919) at Providence College, designed by Matthew Sullivan in the Collegiate Gothic style

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report

BOSTON

“New England Council member Providence College has opened its fifth school, the School of Nursing and Health Sciences. This new school will achieve a goal set by PC’s president, the Rev. Kenneth Sicard, in his inaugural address, on Oct. 1, 2021.

“The new school will expand Providence College’s academic programs in a field that’s crucial to address the shortage of health-care workers in New England and the rest of the United States. In keeping with the college’s liberal-arts tradition, the curriculum included input from faculty from multiple disciplines. Community members wanted to ensure that the new cohort of students will think critically while studying health care to gain skills to help not only the physical but the mental and spiritual well-being of their future patients. The new school will allow students to step outside their normal course load to be able to study abroad, explore dual-language courses and complete immersive community experiences. PC will begin admission to the new school in the fall semester of 2023.

“Christopher Reilly, chairman of the college’s board of trustees, said, ‘These academic initiatives will enhance Providence College’s impact on society in ways that honor the institution’s mission and heritage. They will create exciting opportunities for our students, guided by our faculty, to prepare for lives of meaningful service in assistance to our neighbors and our communities.”’

Vertigo on the Merrimack

“Palms” (print), by Tewksbury, Mass.-based artist Diane Francis, in the show “Printmaking: From Silly Putty to Silkscreen,’’ at the Arts League of Lowell (Mass.) through Oct. 30.

— Photo courtesy: Arts League of Lowell.

The gallery says that the show features the work of printmakers who span the gamut of styles and techniques. Each artist in the show brings their own spin to the centuries-old medium.

Lowell in 1876, in its industrial heyday.

Tewksbury Hospital is a National Register of Historic Places-listed site on an 800+ acre campus in Tewksbury. The centerpiece of the hospital campus is the impressive 1894 Richard Morris Building ("Old Administration Building") above.

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health runs a 350-bed facility at Tewksbury Hospital, providing medical and psychiatric services to adult patients with chronic conditions. The Public Health Museum in Massachusetts now occupies the Richard Morris Building.

In addition to the hospital and museum, the campus also hosts eight residential substance-abuse programs. Five state agencies have regional offices at Tewksbury, including the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health and the Massachusetts Department of Public Safety. The campus also hosts several non-profit and for-profit private entities, including the Lahey Health Behavioral Services' Tewksbury Treatment Center, Casa Esperanza's Conexiones Clinical Stabilization Services (CSS), the Lowell House's Sheehan Women's Program, the Lowell House Recovery Home, the Middlesex Human Service Agency and the Strongwater Farm Therapeutic Equestrian Center.

Trying to grow bigger trees

In the Great North Woods of northern New Hampshire. The area is famed as a source of lumber and wood pulp for paper-making.

— Photo by Will Leavitt

Adapted from an item in Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The U.S. Department of Agriculture is funding a $30 million pilot program to encourage New England forest owners to help address global warming by growing bigger trees, which store more carbon and provide better wood for the building, furniture and other industries than smaller ones. The program, of course, will have the biggest impact on Maine.

The New England Climate Smart Forest Partnership Project is one of 70 department projects aimed at absorbing carbon from greenhouse-gas emissions.

This project includes “pre-commercial thinning” of trees to let the surviving trees grow larger and faster. Sounds reasonable, but this won’t please wildlife that thrives in areas that are thick with smaller trees and bushes. Indeed, the clearing of strips of forest for electricity lines and fire breaks creates ecosystems for many animals.

Shailly Gupta Barnes: Census data show that anti-poverty programs work

Homeless man in Boston

— Photo by Enver Rahmanov

The Town Farm, in Easthampton Mass. Now called the Easthampton Lodging House, it’s an historic poor farm at 75 Oliver St. It was established in 1890 as an inexpensive way to provide for the town's indigent population, and is the only locally run facility of its type to survive in the state. The property was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1996. Poor farms, which housed the penniless, some of whom paid for this with farm work, were a feature of many New England communities into the 20th Century.

— Photo by John Phelan

Via OtherWords.org

The U.S. Census Bureau recently reported that poverty dropped notably in 2021. Amid a pandemic and widespread economic pain, this is a significant accomplishment.

There are three lessons here — about government programs, about how we measure poverty, and about how far we have left to go.

First, these numbers show that government programs work. After Social Security, refundable tax credits like the expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC) and stimulus payments were the biggest contributors to reducing poverty.

Without them, over 20 million more people would have been poor last year. The expanded CTC alone lifted millions of children above the poverty line and reduced racial inequities among poor children.

These programs worked because they departed significantly from how anti-poverty programs have worked for the past 30 years. They provided direct cash transfers to recipients, without any work requirements or bureaucratic indignities.

Welfare-rights organizers have been pushing for these changes for decades. This year, they were proven right.

But unfortunately, official federal poverty figures still conceal the true number of people who are struggling — and underestimate the scale of our responsibility to help them.

At just $31,000 for a family of four, the federal government’s Supplemental Poverty Measure, or SPM, is far too low. That’s less than half of the typical cost of living for a family this size in rural Mississippi, or just one-third for Chicago. And the official poverty measure, or OPM, is even lower.

I’m the policy director of the Poor People’s Campaign, which defines poverty to include everyone living up to 200 percent of the SPM.

Using this measure, which is still less than median income, we counted 140 million people — or 43 percent of the country — who were poor or one emergency away from being poor before the pandemic. In 2021, this rate went down to about 34 percent, or 112 million people.

This is a significant decrease. But it means over a third of our nation has little to celebrate.

In fact, the population living between 100 percent and 200 percent of the SPM threshold stayed basically the same between 2020 and 2021: nearly 90 million people, just one emergency away from poverty. If we only looked at the poverty rate, we would have missed them entirely.

That means we can and must do more. The expanded CTC expired in December 2021, and there has been no further discussion of reviving stimulus payments — even with the federal minimum wage at its lowest value in 66 years and the cost of living continuing to rise.

This is not to minimize the gains we’ve made. They just remind us that poverty is a policy choice — and fortunately, we can make different choices.

In 2020, there were over 80 million eligible poor and low-income voters. Fifty million of them voted in the presidential contest, accounting for a third of the electorate overall and even higher percentages in key states in the Midwest and South.

These voters share a common interest in securing health care, living wages, decent housing, and safe schools for their kids. If they could be organized to take action together — across race, religion, and other lines of division — we could advance the moral policies we need to fully address poverty.

“What’s hurting me in Kentucky is hurting you in Alabama, in West Virginia, and across the nation,” said Tayna Fogle, a leader in the Kentucky Poor People’s Campaign, earlier this year.

“Can you imagine all the poor and the low-income people coming to the ballot box?” she asked. “What if we did everything we could to make sure that our vote counted? We could overturn this madness that’s going on.”

If poor people vote in the midterms like they did in 2020, we could make another leap towards ending the madness of widespread poverty in the midst of plenty.

Shailly Gupta Barnes is the policy director for the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival and the Kairos Center.

Antler art

Basket by Maine artist Sarah Sockbeson at the Portland Museum of Art.

The museum says:

Her work “offers insight into Wabanaki basketry as an ever-evolving art form. The incorporation of deer antler, which Sockbeson cuts, carves, and polishes herself, has emerged as a kind of signature—her personal inflection to a practice that both upholds and updates established techniques.’’

The Abenaki are an indigenous people of the Northern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was predominantly spoken in Maine, while the Western Abenaki language was spoken in Quebec, Vermont and New Hampshire.

Dark green shows the territory of the Eastern Abenaki.

So there’s no uranium mining in Vermont

Murray Bookchin, who moved to Vermont from New York City.

“You see my residence is in New England, and New England has a strong tradition of localism. What is ordinarily called election day in most of the United States is called town meeting day in Vermont. And there are town meetings that are to one degree or another active, however vestigial their powers. They, for example, banned uranium mining in the Green Mountains of Vermont. And the governor of the state was forced to knuckle down to that even though he wanted uranium mining. A number of town meetings—not very large a number but at least a majority of those who had it on their agenda—voted for a nuclear arms moratorium. They’re taking up issues like that at town meetings. What we would like to do if we could is foster, at least in Vermont, greater local power, discussions around issues that are not simply immediate local issues. We would like to raise broad issues at these town meetings and turn them into discussion arenas and interlink the various assemblies and town meetings or try to help create growth of this type of local municipal power—communal power—a view toward, very frankly, establishing a grass-roots self-management institutional framework or network. Now this may be a pure dream, a hopeless ideal, but it’s meaningless for us to go to factories, I can tell you that much.’’

— Murray Bookchin (1921-2006), author, democratic socialist, writer and environmentalist.

Surprise airborne invasion

“Soft Landing” (encaustic collage, ink), in the large group show “Flights of Fancy,’’ at Gallery Twist, Lexington, Mass., through Oct. 16.

William Barnes Wollen’s painting of the Battle of Lexington, which took place on April 19, 1775. With the Battle of Concord the same day, it was the start of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783)

It’s at the National Museum of the U.S. Army, in Fort Belvoir, Va.

Including our diminished things

An Ovenbird

— Photo by Christoph Moning

There is a singer everyone has heard,

Loud, a mid-summer and a mid-wood bird,

Who makes the solid tree trunks sound again.

He says that leaves are old and that for flowers

Mid-summer is to spring as one to ten.

He says the early petal-fall is past

When pear and cherry bloom went down in showers

On sunny days a moment overcast;

And comes that other fall we name the fall.

He says the highway dust is over all.

The bird would cease and be as other birds

But that he knows in singing not to sing.

The question that he frames in all but words

Is what to make of a diminished thing.

— “The Ovenbird,’’ by Robert Frost (1874-1963). Ovenbirds breed in New England, among other north temperate zone areas, and winter around the Caribbean.

David Warsh: To come back, print editions of newspapers must solve intricate production problem

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The off-lead story in the Sept. 18 New York Times, illustrated by a fraying American flag, was one of a series: “Democracy Challenged: twin threats to government ideals put America in uncharted territory.” Senior writer David Leonhardt identified two distinct perils: a movement in one major party to refuse to accept election defeat, and a Supreme Court at odds with public opinion. Leonhardt’s argument was well reasoned and deftly written, enough to fill four pages after the jump.

To my mind, though, The Times is overlooking a problem even more fundamental to the conduct of American democracy: the concentration of power in the quartet of daily newspapers that remain at the top of the first-draft-of-history narrative chain. The loss of diversity of news and opinion among metropolitan newspapers in the 50 American states over the last thirty years has not been well understood.

Media proprietor Rupert Murdoch bought The Wall Street Journal from the Bancroft family, in 2007. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos bought The Washington Post from the Graham family, in 2012. Japanese media group Nikkei acquired the Financial Times from Pearson publishers, in 2015. The New York Times, a fifth-generation family-controlled firm, retains its independence. But Bloomberg LP, an all-digital software analytics and media company, also based in midtown Manhattan, remains looking over its shoulder.

Meanwhile, major metropolitan daily newspapers across the country have been sold and diminished, or collapsed altogether, in the 32 years since the World Wide Web was introduced. These include the Chicago Tribune and its many subsidiaries, among them the Los Angeles Times, The Baltimore Sun, The Hartford Courant and the New York Daily News; The Providence Journal; The Philadelphia Inquirer and 31 other Knight Ridder newspapers, including The Miami Herald and San Jose’s Mercury News; Cleveland’s Plain Dealer, Portland’s Oregonian and New Orleans’s Times-Picayune, among the Newhouse newspaper chain; the Louisville Courier-Journal; the Arizona Republic; Las Vegas Sun, and Dean Singleton’s Denver Post. The Daily Bee, founded in Sacramento in 1857, part of all but the last surviving family-owned newspaper chain, declared bankruptcy in 2020, though the Atlanta Journal-Constitution remains the flagship of Cox Enterprises. Only Texas and Florida maintain several competitive metropolitan newspapers. The Christian Science Monitor ceased publishing a paper edition in 2009, while maintaining a digital presence.

What happened? Google and Facebook entered the advertising business. Antitrust newsletter writer Matt Stoller recently described Google’s rollup of the search-intermediary industry over the course of a decade, notably its 2007 acquisition of DoubleClick, into the voracious advertising sales business that the former “free” search engine enterprise has become. Facebook did much the same. The result was that newspapers lost some 80 percent of their advertising revenues in a decade. More than 2,000 papers went out of business altogether.

In a similar vein, The New Goliaths: How Corporations Use Software to Dominate Industries, Kill Innovation, and Undermine Regulation (Yale, 2022), by James Bessen, makes a compelling case that “dominant firms have used proprietary technology to achieve persistent competitive advantages and persistent market dominance,” by more effectively managing market complexity in industries of all sorts.

Strengthening antitrust enforcement is a good idea, Bessen says, but breaking up firms is unlikely to solve the “superstar problem.” A more effective solution has to do with opening up access to knowledge, which means addressing ubiquitous intellectual-property bottlenecks. Market-driven unbundling – the process that, in the 1970s, led IBM to open its proprietary software to independent applications, and, in the Oughts, Amazon to make its information technology software available to other vendors on its proprietary servers – offer more promising possibilities, he asserts in a closing chapter. Bessen heads a research initiative at Boston University’s Law School. The New Goliaths is an important book. Let’s hope it get the attention it deserves.

American democracy is not doomed to a future dominated by four or five national newspapers. There is reason to believe that the market for home-delivered newsprint newspapers is much broader than it now seems, though it may take years to revive it. Radio returned to prosperity after television advertising all but destroyed its formerly lucrative advertising business. Newsprint thrived for nearly a hundred years despite the entry of both.

To come back from the online onslaught, however, print newspapers must solve an intricate coordination problem, involving every aspect of the business. These include the cost of newspaper production, from newsprint to software to printing facilities; the riddle of subscription pricing; the restoration of home delivery networks; and the reconstruction of advertising sales. Moreover, the new newsprint goliaths must cooperate with big city dailies seeking to regain market share if the problem is to be solved.

Take, for example, a narrow slice of the cost of production problem: the software that enables editors to simultaneously assemble and publish both print and online content. Dan Froomkin, a former Washington Post columnist, reports in The Washington Monthly, that Amazon’s Bezos, upon acquiring The Post, discovered that the process was wildly inefficient, whereupon he tasked chief information officer Shailesh Prakesh to fix it.

The result: a best-in-class publishing platform, Arc XP, that the Post now uses to publish its own product, and licenses to 2,000 other media and non-media sites. But the license, Froomkin says, is expensive. His suggestion: that Bezos do as Andrew Carnegie did with his libraries more than a century ago, and make Arc XP available free to other newspaper publishers, along with its companion Zeus Technology ad-rendering platform. It is an interesting proposal. So is the multi-state antitrust lawsuit against Google and Facebook, slowly making its way in a U.S. District Court. Meanwhile, the bipartisan Journalism Competition and Preservation bill inched forward last week, when the Judiciary Committee voted 15-7 to send it to the Senate floor

What size might be the market for subscriber-based print, supplemented by traditional advertising? At what annual price? There is simply of no way of telling besides customary trial and error. Let’s hope that the new newsprint goliaths will participate in the learning. True, the four national papers and Bloomberg do a pretty good job of gathering news on their own. But it seems clear that the American democracy functioned better when there were more strong voices scattered across its landscape. It makes sense to search for ways by which those circumstances can be restored – plenty of fodder for future columns.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com.

Editor’s note, a few newspapers, most notably in New England The Boston Globe, now under control of the Boston-based Henry family, still retain much, but far from all, of their former journalistic package.