Don Pesci: An apolitical and literary jaunt in The Berkshires

A view of the Mt. Greylock Range from South Williamstown (from the west). The Hopper, a cirque, is centered below the summit.

—Photo by Ericshawwhite

Arrowhead, where Herman Melville wrote Moby Dick.

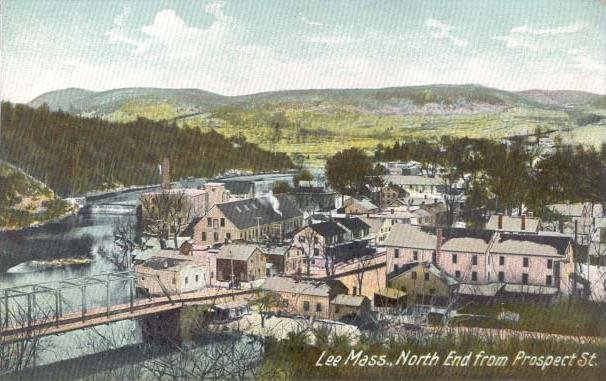

Lee, Mass., in The Berkshires, is everyone’s vision of a typical New England town. The Main Street is short and to the point. Buildings, unmolested by town planners, have maintained their character throughout the years. The house where we bunked for several days dates from the 19th Century and has been well kept by its owner, an engineer who had, like Odysseus, moved about in the world. He was born, very likely in or near the house we occupied, moved with his family to Washington, D.C., where his father had found a job that he could not refuse as an electrical engineer, and later back to Lee.

The firehouse across the street from Garfield House, where we stayed, is a solid stone structure that boasts a square steeple that one easily might mistake for a bell tower or a medieval watch tower.

Traveling around New England, one must – delicately, delicately – approach the topic of politics. Open wounds are everywhere. Much of New England is solid ultramarine blue (there are dramatic exceptions, such as Aroostook County, Maine). That is to say that many people in New England wish to see former Donald Trump in leg irons waltzing through a prison yard. My wife, Andrée, believes that such emotions are far too enthusiastic. She taught American Studies for many years and is intimately familiar with the religious enthusiasms of the 17th Century that saw a witch behind every bush.

Trump, she likes to say when not in the presence of people still suffering political whiplash from the 2016 Hillary Clinton/Donald Trump campaign, is, in some respects, a man more sinned against than sinning, though, of course, she would never say such things in the presence of those who wish to burn Trump at the stake – which is to say, in a good deal of New England. Consider that Democrats in Connecticut, a part of New England and our home state, outnumber Republicans by a two-to-one margin, with unaffiliateds topping Democrats by a small number.

Andrée laid down the law long ago: There will be no politics spoiling our vacations. This law of the household precedes Trump’s ascendency to the presidency by, say, a half century or more. No politics means no computers, no cell phones, no newspapers, no furtive notes written in the shadows, and only mercifully brief encounters with witch-burners.

“Just change the subject, will you?”

In very few places throughout the world -- Washington, D.C., of course, other uncivilized places that used to be part of the British Empire, including most of New England, and Italy— everywhere and always – political talk with strangers destroys the moment, and living in the moment is essential to travel. In Florence, Italy, we almost missed, through dreamy inattention, the spot where Savonarola had been burned at the stake. It is a grave sin to have eyes and not see, ears and not hear, when traveling about the world.

Just ask Odysseus, a victim of enchantment and forgetfulness during the year he spent, not unpleasantly, with Circe. First, the traveler forgets where he is, then who he is, and then the once-solid world dissolves like a dream.

“Pay attention!”

It was no chore for us to pay attention to Herman Melville, most famous, of course, as the author of Moby Dick. In college, he was our literary touchstone. One day, early in our marriage, I brought home a little-read book by Melville, Pierre or the Ambiguities. It’s a romance novel, and Andrée, an incurable romantic, fell for it head over heels. A little later, though we already had been married a couple of years, she fell for me, not quite head over heels.

We had visited Arrowhead, Melville’s home in Pittsfield, years earlier when the house was in transition. No one was home, the house, garnet-red at the time, was dark and forbidding and vacant. Even the spirit of the place had taken flight. We peeked in the windows. Off in the background, Mt. Greylock, the highest elevation in Massachusetts, showed his hump.

Melville wrote Moby Dick in this house. He dedicated the book to his good friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, then living part time in nearby Lenox. The book following Moby Dick, Pierre or the Ambiguities, was dedicated as follows: “'To Greylock's Most Excellent Majesty ... the majestic mountain, Greylock — my own more immediate sovereign lord and king — hath now, for innumerable ages, been the one grand dedicatee of the earliest rays of all the Berkshire mornings, I know not how his Imperial Purple Majesty ... will receive the dedication of my own poor solitary ray ...''

Greylock, we found, was full of winding ways, but so was Melville’s route through a tortuous world. Moby Dick, now considered a classic American novel, was a conspicuous failure in its day. And it was only after Melville had died that the book rose from its deadening reviews.

Today, as always, the book must be read aloud, not so much with the eye as with the ear of the heart. It is music to the ear and, like all music, it winds its way over long Shakespearian passages, moving gracefully at its own pace. It was this music that had enchanted Andrée so many years ago.

The trip to Arrowhead reminded me that traveling is an inward experience, not merely a collection of interesting photos taken of interesting places along the way.

Mark Twain, a Connecticut resident for many years, traveled widely in Europe. And partly on the basis of that, he wrote a little-read book he considered his best: “I like Joan of Arc best of all my books… It furnished me seven times the pleasure afforded me by any of the others; twelve years of preparation, and two years of writing. The others needed no preparation and got none.” (The full name of the novel is Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc.)

Twain was anti-clerical, not necessarily anti-religious. But the character of Joan, buried for many years under heaps of anti-Catholic perfidy, was paramount for Twain: “Taking into account…all the circumstances—her origin, youth, sex, illiteracy, early environment, and the obstructing conditions under which she exploited her high gifts and made her conquests in the field and before the courts that tried her for her life—she is easily and by far the most extraordinary person the human race has ever produced.”

The Mount, novelist Edith Wharton’s plush estate in Lenox, is only a 10-minute ride from Garfield House.

There’s a picture on one wall in the estate’s mansion of a salon gathering in which Henry James makes an appearance. Anything Jamesian is redemptive for Andrée. As an American Studies and American Literature teacher for many years, both in Catholic and public schools, she taught James and other famed authors to students who eventually came to appreciate James’s long winding prose paths – very Shakespearian and even Melvillean.

Twain was not a James fancier: “Once you put him down, you can’t pick him up again.”

But Andrée likes the winding ways of a strong – dare I say it? -- Faulknerian sentence, very much like the path the imagination takes when it is called into service in our travels.

Our next-door neighbor at Garfield House, a permanent resident and an expat from New York, told us that she had lived for a time in Wharton’s reading room while she was an administrator of the Shakespearian Company that put on plays at The Mount.

“You were an actress?”

“Oh, God no, please no – not an actress. I worked behind the scenes as an administrator to put on the plays.”

“In New York?”

“Yes. New York had become too cloying, so I came here, fell in love with the place and stayed. By the way, you told me that you like golf, but you do not like golfers. Just a word to the wise: You had better not say that to the proprietor of Garfield House, who is an avid golfer.”

I agreed, as Andrée said, to “change to subject” if it came round to golf.

Golf, like politics in New England, has become in recent days a secular religion full of saints and heretics – none of them, unfortunately, quite like St. Joan of Arc.

Twain on politics: “In religion and politics people’s beliefs and convictions are in almost every case gotten at second-hand, and without examination, from authorities who have not themselves examined the questions at issue but have taken them at second-hand from other non-examiners, whose opinions about them were not worth a brass farthing.”

Now there, Andrée might say, is a near perfect Jamseian sentence, very much like the hiker’s paths that cross and re-cross Mount Greylock. Our very last adventure before leaving Lee for home was to ride – not walk – to the top of Melville’s “sovereign lord and king.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn., based columnist.

Front Entrance of The Mount.

— Photo by Margaret Helminska

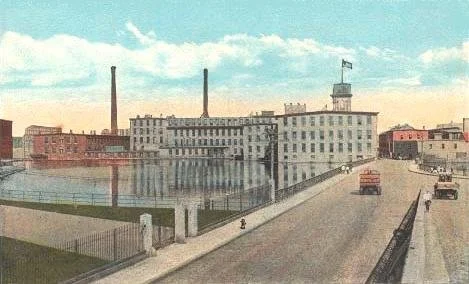

1907 postcard.

Sonali Kolhatkar: Ehrenreich took apart the American cult of ‘positive thinking’

Boston swindler and con man Charles Swindler (1882-1949), who promoted positive thinking in his investors and whose career is the origin of the phrase “Ponzi Scheme.’’

Via Other Words.org

The late Barbara Ehrenreich was best known for her 2001 bestseller Nickel and Dimed, which showed that hard-working people simply weren’t making it in America.

But Ehrenreich, who died Sept. 1 at 81, made an equally great contribution to economic justice with her subsequent book, Bright-Sided. It argued that the cult of “positive thinking” was putting a smiley face on inequality and “undermining America.”

Bright-Sided was published in 2009, between the Great Recession and the Occupy Wall Street movement, which called attention to the stark economic split between the wealthiest “1 percent” of Americans and the “99 percent” of everyone else.

I had the honor of interviewing Ehrenreich during this period. She explained that “there is a whole industry in the United States invested in this idea that if you just think positively, if you expect everything to turn out alright, if you’re optimistic and cheerful and upbeat, everything will be all right.”

Ehrenreich, who had cancer, said she began her investigation into the ideology of positive thinking when she had breast cancer, roughly six years before Bright-Sided was published. That’s when she realized what a uniquely American phenomenon it was to put a positive spin on everything.

She applied that idea to economic inequality, discovering an entire industry telling struggling Americans that their poverty stemmed from their own negative thinking. It promised they could turn things around if they simply “visualized” wealth, embraced a “can-do” attitude, and willed money to flow into their lives.

Central to this industry are “the coaches, the motivational speakers, the inspirational posters to put up on the office walls,” said Ehrenreich — and many megachurches and multi-millionaire “prosperity gospel” preachers, too. “The megachurches are not about Christianity. The megachurches are about how you can prosper because God wants you to be rich,” she said — adding that in many of them, “you won’t even find a cross on the wall.”

But the cult of positive thinking ultimately has more secular roots. “It grew because corporations needed a way to manage downsizing, which really began in the 1980s,” she said. Businesses that laid off masses of employees had a message that “you’re getting eliminated… but it’s really an opportunity for you. It’s a great thing; you’ve got to look at this positively. Don’t complain.”

Eventually, Americans internalized the idea that losing one’s job has got to be a sign that something better is coming along and that “everything happens for a reason.” The alternative is to blame one’s employer, or even the design of the U.S. economy. And that would be dangerous to Wall Street and corporate America.

Another purpose of fostering positive thinking among those who are laid off, according to Ehrenreich, is “to extract more work from those who survive layoffs.” After all, those who remain employed ought to feel lucky to have a job — even if it means working late hours, working on the weekends, and taking on exhaustive responsibilities. More positive thinking.

Thankfully, Ehrenreich may have lived to see a breaking point.

Since the pandemic, we’ve seen a “great resignation,” a term for masses of Americans quitting thankless jobs. And, more recently, “quiet quitting,” where workers only put in the hours they’re paid to work and no more. How novel!

We owe Ehrenreich a debt of gratitude for shining a light not only on the perversity of the U.S. economic system, but also on the gauzy veil of positive thinking that obscures it.

Sometimes, positive change needs to begin with some not-so-positive thinking..

Ehrenreich may not have lived to see her ideas of economic justice fully realized. But, as she once told The New Yorker, “The idea is not that we will win in our own lifetimes… but that we will die trying.”

Sonali Kolhatkar is the host of Rising Up With Sonali, television and radio show on Free Speech TV and Pacifica stations. This commentary was produced by the Economy for All project at the Independent Media Institute and adapted by OtherWords.org.

In Boston, the original Christian Science Mother Church (1894) and behind it the domed Mother Church Extension (1906); on the right, the Colonnade building (1972). The reflecting pool is in the foreground. Christian Science, founded in New England in the late 19th Century, is big on “positive thinking.’’

‘Had their look down’

Wesleyan University’s Samuel Wadsworth Russell House, built in 1828, home to the school’s Philosophy Department. The building was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2001 and is considered one of the finest examples of Greek Revival architecture in the country.

“I remember I grew up in Pasadena in a very, kind of, homogeneous, kind of, suburban existence and then I went to college at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. And there were all these, kind of, hipster New York kids who were so-called 'cultured' and had so much, you know, like knew all the references and, like, already had their look down.’’

Mike White (born 1970), screenwriter and actor

What they’ll remember

— Photo by kallerna

“In early autumn, there’s a concerto

possible when there’s a guest in the house

and the guest is taking a shower and the host

is washing up from the night before….

‘‘Much later they will remember only a color,

a golden yellow, and the sound of their feet

scuffling the leaves. A day without rancor….’’

— From “The Music One Looks Back On,’’ by Boston-based poet Stephen Dobyns (born 1941)

Surreal view

“North Head Afternoon’’ (oil painting), by Evan McGlinn, at the Southern Vermont Arts Center, Manchester, in its “Fall 2022 Solo Exhibitions,’’ through Nov. 6.

The gallery says the show features 10 artists representing “a wide range of mediums and styles from photography to painting to etching.’’

Mr. McGlinn's "North Head Afternoon" is “a surreal snapshot of a classic New England scene. The oil painting behind the three bottle-lined windows seems to glow from within, illuminating the space.’’

A romantic route coming?

Long but scenic: Proposed route of Boston-Montreal sleeper train.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

What a neat idea! For years, government officials and businesspeople in New England and Quebec have talked of running an overnight sleeper train, with dining and club cars and even entertainment, from Boston to Montreal, via southern Maine and then up through New Hampshire’s White Mountains and Quebec’s Eastern Townships. Now, spearheaded by a Quebec organization called Fondation Trains de Nuit, the initiative is gaining speed, although the service probably couldn’t start until 2025-2026.

A couple of hundred million dollars would probably be needed to bring the the proposed route, all owned by private railroads, up to passenger-rail standard, but studies suggest it could be successfully marketed. For one thing, it would connect two large and dynamic metro areas (good for the economies of both); for another, projections are that the service’s tickets would cost considerably less than ones to fly, and perhaps most alluring, it would offer a fun, romantic and low-stress route through scenic terrain. And fewer young people these days want to drive.

A friendly reminder

From North Adams, Mass.-based painter Julia Dixon’s current show. “Memento Mori,’’ at the Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Mass.

She says of her show:

“My current painting series … depicts individuals in arresting scenes in order to confront viewers about time and impermanence. These paintings, as well as smaller oil and watercolor studies of skulls, insects, flowers, and other symbolic objects, are meditations on the inevitability of death while, at the same time, affirmations of the beauty and tenderness of life….

“My interest is in juxtaposing symbols hidden in Christian artworks and classical still lives, particularly those of the Dutch Golden Age, with modern secular environments and nature to explore the emotional implications of presence and absence, fear, futility, and legacy.’’

Park Square in downtown Pittsfield in 2014

— Photo by Protophobic

Llewellyn King: The talent shortage that imperils journalism

In the newsroom of the still successful New York Times.

Boston’s Newspaper Row, circa 1906, showing the locations of The Boston Post (left), The Boston Globe (center-left) and The Boston Journal (center-right).

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

“Journalists can be so good at reporting others, but are seldom good at reporting {on} themselves.”

That is what my friend Kevin d’Arcy, a distinguished British journalist, wrote in an article titled “Living in Interesting Times,” published recently on the Web site of the United Kingdom Chapter of the Association of European Journalists.

D’Arcy, who has worked for major publications in the U.K. and Canada, including The Economist and the Financial Times, argues, “The biggest change is that the job of journalism no longer belongs to journalists alone. To some extent this has always been true but, largely because of social media, the scale is touching the sky.

“This matters for the simple reason that the public lacks the traditional protection of legal and social rules. There is nobody in control. … The common realm is sinking fast.”

So true. But his argument raises the question: Is journalism itself doing its job these days?

I usually eschew discussion about journalism — its present state, imagined biases and its future. Dan Raviv, a former correspondent for CBS News on radio and television, told me in a television interview, “My job is simple: I try to find out what is going on, then I tell people.”

I have never heard the job of a journalist better explained.

Of course, the journalist knows other things: the tricks of the trade, such as news judgment; how to get the reader reading, the viewer watching, and the listener listening and, hopefully, to keep their attention.

Professionals know how to guesstimate how much readers, viewers and listeners might want to know about a particular issue. They know how to avoid libel and keep clear of dubious, manipulative sources.

But journalism’s skills are fading, along with the newspapers and the broadcast outlets that fostered and treasured them.

Publications are dying or surviving on an uncertain drip from a life-support system. Newspapers that once boasted global coverage are now little more than pamphlets. The Baltimore Sun, for example, in its day a great newspaper, once had 12 overseas bureaus. No more.

Three newspapers dominate America: The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post and The New York Times. They got out in front and owe their position there to successfully pushing their brands on the Internet early. Now they have still have lots of advertising revenue from their print versions, and increasing revenue from their Web sites, with their pay walls.

Local news coverage may come back as it once was, but this time through local digital sites. I prefer traditional newspapers, but the future of local news appears to be online.

A major and critical threat to journalism comes from within: It is a dearth of talent. You get what you pay for; publishers aren’t paying for talent, and that is corrosive. Newspaper and regional TV and radio salaries have always been abysmally low, and now they are the worst they have been in 50 years. This is discouraging needed talent.

For more than 30 years, I owned a newsletter-publishing company in Washington, D.C., and I hired summer interns — and paid them. Some of the early recruits went on to success in journalism, and some to remarkable success.

Latterly, I got the same bright journalism students — young men and women so able that you could send them to a hearing on Capitol Hill or assign them a complex story with confidence.

The most gifted, alas, weren’t headed for newsrooms, but for law school. They told me that as much as they were interested in reporting, they weren’t interested in low-wage lives.

Most reporters across America earn less than $40,000. Even at the mighty Washington Post, a unionized newspaper, beat reporters make just $62,000 a year.

To tell the story of a turbulent world, you need gifted, creative, well-read people, committed to the job. The bold and the bright are not going to commit to a life of penury.

To my friend Kevin, I must say, If we can’t offer a viable alternative to the social-media cacophony, if we have a workforce of the second-rate, if the news product is inadequate, and untouched by knowledgeable human editors, then the slide will continue. Editing by computer is not editing. I appreciate editing, and I know how much better my work is for it.

The journalism that Kevin and I have reveled in over these many decades will perish without new talent. Talent will out, and hopefully provide the answers that our trade needs.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C. He was an editor at The Washington Post and some other large papers in America and England.

For last time until spring?

“Path through the Dunes” (oil on canvas), by Vermont-based artist, writer and farmer Greg Bernhardt, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

His artist says:

“I am a painter living in central Vermont on a farm that my wife, Hannah Sessions, and I began 20 years ago. With animal husbandry and producing award winning cheeses as the reason why we live where we do, painting and writing has been the method by which we understand what we do here.

Blue Ledge Farm affords us an intimate look at the relationship between people and animals, and an appreciation of the land as we spend the vast amount of our time on this plot of earth and have come to know it as deeply as we could anything.

Since having majored in Studio Art and Creative Writing at Bates College (in Maine) in the late ’90s, and having lived abroad studying the Italian language, Renaissance Art, and Italian Literature in Florence, Italy 1997-1998, I have aimed to merge the central themes of my life and found in the end that all these focal points rely on one another, the farm and its inhabitants, the artisanal cheese craft, and the creative acts of writing and painting about these subject matters.’’

Companies’ creepy surveillance of their own workers

The evil dictator in George Orwell’s 1984

Via OtherWords.org

For generations, workers have been punished by corporate bosses for watching the clock. But now, the corporate clock is watching workers.

Called “digital productivity monitoring,” this surveillance is done by an integrated computer system including a real-time clock, camera, keyboard tracker, and algorithms to provide a second-by-second record of what each employee is doing.

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos pioneered use of this ticking electronic eye in his monstrous warehouses, forcing hapless, low-paid “pickers” to sprint down cavernous stacks of consumer stuff to fill online orders, pronto — beat the clock, or be fired.

Terrific idea, exclaimed taskmasters at hospital chains, banks, tech giants, newspapers, colleges, and other outfits employing millions of mid-level professionals.

They’ve been installing these unblinking digital snoops to watch their employees, even timing their bathroom breaks and constantly eying each one’s pace of work. They’ve plugged in new software with such Orwellian names as WorkSmart and Time Doctor to count worker’s keystrokes and to snap pictures every 10 minutes of workers’ faces and screens, recording all on digital scoreboards.

You are paid only for the minutes the computers “see” you in action. Bosses hail the electronic minders as “Fitbits” of productivity, spurring workers to keep noses to the grindstone, and also to instill workplace honesty.

Only… the whole scheme is dishonest.

No employee’s worthiness can be measured in keystrokes and 10-minute snapshots! What about thinking, conferring with colleagues, or listening to customers? No “productivity points” are awarded for that work.

For example, The New York Times reports that the multibillion-dollar United Health Group marks its drug-addiction therapists “idle” if they are conversing off-line with patients, leaving their keyboards inactive.

Employees call this digital management “demoralizing,” “toxic,” and “just wrong.” But corporate investors are pouring billions into it. Which group do you trust to shape America’s workplace?

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker.

'Persistent interrogation'

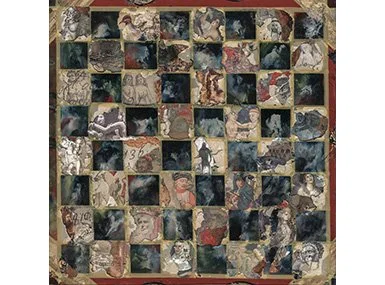

“Checkerboard ("It's How You Play the Game"), (mixed-media collage). by Greater Boston artist Rosamond Purcell, in her first retrospective show, “Nature Stands Aside,’’ at the Addison Gallery, at Phillips Andover Academy, Andover, Mass., through Dec. 31.

The gallery says:

“Murre eggs nestled in cotton that appear to have been decorated by an overzealous Abstract Expressionist, a blanched piranha charging ahead in a glass jar of orange-tinged formaldehyde, a cast off typewriter transformed by time into an octopean tangle of rusticles. From luscious large format Polaroid prints to objects rescued from obscurity, the empathetic, evocative, and multifaceted work of the photographer and conceptual artist Rosamond Purcell (born 1942) explores the ill-defined interstices between the unsettling and the sublime, the beautiful and the bizarre, the natural and the manufactured. As a body of work, it lays bare humanity’s desperate desire to collect and make sense of it all.

“Over a career spanning some fifty years, Purcell has collaborated with paleontologists, anthropologists, historians, museum curators, termite experts, and even a scholar-magician to illuminate and explore the shifting boundaries between art and science. She has found some of her greatest inspiration in long-overlooked storage spaces in natural history museums across the world and in the hills and the shacks of a 13-acre junkyard located in an otherwise picturesque Maine coastal town. Purcell’s six decades of work, while brilliantly varied and resistant to easy classification, speaks eloquently to the artist’s persistent interrogation of the ways in which humanity has and continues to attempt, often fruitlessly, to understand the world around it.”

Parasite state

Terminal of Manchester-Boston Regional Airport, whose name is aimed at grabbing Greater Boston business.

— Photo by MaxVT

“As part of the regional metro-Boston area, southern New Hampshire offers all the benefits typically associated with major metro areas yet maintains the advantages of being in a truly enterprise-friendly state: access to a world-class workforce, a pro-business, low-tax environment, and a streamlined regulatory environment.’’

— New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu

Omicron boosters: Is salesmanship trumping science?

Moderna headquarters in Cambridge, Mass.

Last month, the Food and Drug Administration authorized Omicron-specific vaccines (with Moderna’s the best known), accompanied by breathless science-by-press release and a media blitz. Just days after the FDA’s move, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention followed, recommending updated boosters for anyone age 12 and up who had received at least two doses of the original COVID-19 vaccines. The message to a nation still struggling with the COVID pandemic: The cavalry — in the form of a shot — is coming over the hill.

But for those familiar with the business tactics of the pharmaceutical industry, that exuberant messaging — combined with the lack of completed studies — has caused considerable heartburn and raised an array of unanswered concerns.

The updated shots easily clear the “safe and effective” bar for government authorization. But in the real world, are the Omicron-specific vaccines significantly more protective — and in what ways — than the original COVID vaccines so many have already taken? If so, who would benefit most from the new shots? Since the federal government is purchasing these new vaccines — and many of the original, already purchased vaccines may never find their way into taxpayers’ arms — is the $3.2 billion price tag worth the unclear benefit? Especially when these funds had to be pulled from other covid response efforts, like testing and treatment.

Several members of the CDC advisory committee that voted 13-1 for the recommendation voiced similar questions and concerns, one saying she only “reluctantly” voted in the affirmative.

Some said they set aside their desire for more information and better data and voted yes out of fear of a potential winter COVID surge. They expressed hope that the new vaccines — or at least the vaccination campaign that would accompany their rollout — would put a dent in the number of future cases, hospitalizations, and deaths.

That calculus is, perhaps, understandable at a time when an average of more than 300 Americans are dying of COVID each day.

But it leaves front-line health care providers in the impossible position of trying to advise individual patients whether and when to take the hot new vaccines without complete data and in the face of marketing hype.

Don’t get us wrong. We’re grateful and amazed that Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna (with assists from the National Institutes of Health and Operation Warp Speed) developed an effective vaccine in record time, freeing the nation from the deadliest phase of the covid pandemic, when thousands were dying each day. The pandemic isn’t over, but the vaccines are largely credited for enabling most of America to return to a semblance of normalcy. We’re both up-to-date with our covid vaccinations and don’t understand why anyone would choose not to be, playing Russian roulette with their health.

But as society moves into the next phase of the pandemic, the pharmaceutical industry may be moving into more familiar territory: developing products that may be a smidgen better than what came before, selling — sometimes overselling — their increased effectiveness in the absence of adequate controlled studies or published data, advertising them as desirable for all when only some stand to benefit significantly, and in all likelihood raising the price later.

This last point is concerning because the government no longer has funds to purchase COVID vaccines after this autumn. Funding to cover the provider fees for vaccinations and community outreach to those who would most benefit from vaccination has already run out. So updated boosters now and in the future will likely go to the “worried well” who have good insurance rather than to those at highest risk for infection and progression to severe disease.

The FDA’s mandated task is merely to determine whether a new drug is safe and effective. However, the FDA could have requested more clinical vaccine effectiveness data from Pfizer and Moderna before authorizing their updated omicron BA.5 boosters.

Yet the FDA cannot weigh in on important follow-up questions: How much more effective are the updated boosters than vaccines already on the market? In which populations? And what increase in effectiveness is enough to merit an increase in price (a so-called cost-benefit analysis)? Other countries, such as the United Kingdom, perform such an analysis before allowing new medicines onto the market, to negotiate a fair national price.

The updated booster vaccine formulations are identical to the original covid vaccines except for a tweak in the mRNA code to match the omicron BA.5 virus. Studies by Pfizer showed that its updated Omicron BA.1 booster provides a 1.56 times higher increase in neutralizing antibody titers against the BA.1 virus as compared with a booster using its original vaccine. Moderna’s studies of its updated Omicron BA.1 booster demonstrated very similar results. However, others predict that a 1.5 times higher antibody titer would yield only slight improvement in vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic illness and severe disease, with a bump of about 5 percent and 1 percent, respectively. Pfizer and Moderna are just starting to study their updated Omicron BA.5 boosters in human trials.

Though the studies of the updated Omicron BA.5 boosters were conducted only in mice, the agency’s authorization is in line with precedent: The FDA clears updated flu shots for new strains each year without demanding human testing. But with flu vaccines, scientists have decades of experience and a better understanding of how increases in neutralizing antibody titers correlate with improvements in vaccine effectiveness. That’s not the case with COVID vaccines. And if mouse data were a good predictor of clinical effectiveness, we’d have an HIV vaccine by now.

As population immunity builds up through vaccination and infection, it’s unclear whether additional vaccine boosters, updated or not, would benefit all ages equally. In 2022, the U.S. has seen COVID-hospitalization rates among people 65 and older increase relative to younger age groups. And while COVID vaccine boosters seem to be cost-effective in the elderly, they may not be in younger populations. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices considered limiting the updated boosters to people 50 and up, but eventually decided that doing so would be too complicated.

Unfortunately, history shows that — as with other pharmaceutical products — once a vaccine arrives and is accompanied by marketing, salesmanship trumps science: Many people with money and insurance will demand it whether data ultimately proves it is necessary for them individually or not.

We are all likely to encounter the SARS-CoV-2 virus again and again, and the virus will continue to mutate, giving rise to new variants year after year. In a country where significant portions of at-risk populations remain unvaccinated and unboosted, the fear of a winter surge is legitimate.

But will the widespread adoption of a vaccine — in this case yearly updated COVID boosters — end up enhancing protection for those who really need it or just enhance drugmakers’ profits? And will it be money well spent?

The federal government has been paying a negotiated price of $15 to $19.50 a dose of mRNA vaccine under a purchasing agreement signed during the height of the pandemic. When those government agreements lapse, analysts expect the price to triple or quadruple, and perhaps even more for updated yearly COVID boosters, which Moderna’s CEO said would evolve “like an iPhone.” To deploy these shots and these dollars wisely, a lot less hype and a lot more information might help.

Elisabeth Rosenthal (erosenthal@kff.org, @rosenthalhealth) and Céline Gounder (cgounder@kff.org) are Kaiser Health News journalists.

Bella DeVaan, Rebekah Entralgo: Skimping on schools while squandering money on the rich

Plaque on School Street, Boston, commemorating the site of the first Boston Latin School building. Boston Latin, the city’s most prestigious high school, was founded in 1635, before there were “high schools,’’ making it by far the oldest public school in America.

Via OtherWords.org

As students have been returning to the classroom, school districts across the country are facing a historic number of teacher vacancies — an estimated 300,000, according to the National Education Association (NEA), the largest U.S. teachers union.

Some states are particularly hard hit, with approximately 2,000 empty positions in Illinois and Arizona, 3,000 in Nevada, and 9,000 in Florida.

How are political leaders responding? A number of rural Texas districts have moved to a four-day school schedule, creating major hassles for working parents. A new Arizona law will no longer require a bachelor’s degree for full-time teachers. Florida is allowing military veterans to temporarily teach without prior certification. Florida’s Broward County recruited over 100 teachers from The Philippines.

These band-aid actions ignore the root causes of the teacher crisis: low pay and burnout.

A new Economic Policy Institute report finds that teachers made 23.5 percent less than comparable college graduates in 2021. That’s the widest gap ever — despite the extraordinary challenges teachers have faced during the pandemic. The gap is even wider in some of the states with the largest teacher shortages, reaching 32 percent in Arizona, for example.

Across the country, real wages for public school teachers have essentially flatlined since 1996.

When the NEA surveyed teachers earlier this year, 55 percent reported they plan to leave the profession sooner than planned. An overwhelming 91 percent pointed to burnout as their biggest concern, with 96 percent supporting raising salaries as a means to address burnout.

Some states are getting the message: In New Mexico, lawmakers have instituted minimum teacher salary tiers based on experience — beginning at $50,000 and maintaining a $64,000 median wage. They’re also aiming to codify annual 7 percent raises so that teachers don’t lose ground to inflation.

“These raises represent the difference of being on Medicaid with your family, the difference of having to have a second or third job or doing tutoring work on the side, the difference of driving the bus during the day and having to take extra routes just to make ends meet,” said New Mexico teacher John Dyrcz in a recent interview with More Perfect Union.

In other areas, teachers are harnessing their collective bargaining power to make their demands heard. Thousands of teachers in Ohio, Washington state, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C., went on strike during the first weeks of the academic year.

The educators’ union in Columbus, Ohio, demands a simple, public “commitment to modern schools”: not only pay raises but also smaller class sizes, decent air conditioning, adequate funding for the arts and physical education, and caps on numbers of periods taught in a row.

Read one picketer’s sign: “You think we give up easy? Ask how long we wait to PEE!”

Meeting such demands requires public investment. And unfortunately, too many lawmakers favor lining the coffers of the wealthy instead of funding our school systems.

In 2021, the Columbus Dispatch estimates schools in the city lost out on $51 million to local real estate developers. In New York, an over $200 million reduction in school budgets has provoked public outcry in a city where luxury builders have pocketed well over $1 billion in tax breaks each year.

The Columbus teachers union soon came to a “conceptual agreement” with the city’s schools, ending their strike. Let’s hope this is a sign of a turning tide. Through a relentless pandemic, vicious censorship of curricula, and surging inequality, we cannot continue to skimp on education while squandering our resources on the wealthy.

Rebekah Entralgo (@rebekahentralgo) is the managing editor for Inequality.org. Bella DeVaan (@bdevaan) is the research and editorial assistant for Inequality.org.

‘September rain’

Jack Korouac’s grave in Edson Cemetery, Lowell

— Photo by DanielPenfield

“And what does the rain say at night in a small town, what does the rain have to say? Who walks beneath dripping melancholy branches listening to the rain? Who is there in the rain’s million-needled blurring splash, listening to the grave music of the rain at night, September rain, September rain, so dark and soft? Who is there listening to steady level roaring rain all around, brooding and listening and waiting, in the rain-washed, rain-twinkled dark of night?”

― Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), American novelist and poet, in his novel The Town and the City, The novel is set in the early Beat Generation circle of New York in the late 1940s and on Galloway, Mass., based on Lowell. The experiences of the young "Peter Martin" struggling for success on the high school football team are largely those of Jack Kerouac (he returns to the subject again in his last work, Vanity of Duluoz, published in 1968).

David Warsh: Blame Harvard

The Taubman Building at Harvard’s Kennedy School.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

A “Freudian slip,” according to Wikipedia, is “an error in speech, memory, or physical action that occurs due to the interference of an unconscious subdued wish or internal train of thought.” Slips of the tongue are classic examples, but other manifestations include “misreadings, mishearings, mis-typings, temporary forgetting, and the mislaying and losing of objects.” The insight is a vivid reminder of what was learned from the 20th Century discipline known as psychoanalysis: some, definitely, but perhaps not as much as they thought.

I committed an act of misstatement that requires more explanation than mere correction when I recently wrote that “[Boris] Yeltsin…presided over a decade of ‘shock therapy,’ a massive helter-skelter privatization of government-owned Russian assets based largely on ideas propounded in College Park, Md., and Cambridge, Mass.”

College Park had nothing to do with what happened next.

Its IRIS Center, an economic strategy and development advisory service based at the Beltway campus of the University of Maryland, was founded in 1990. Even the source of its acronym, if there was one, is now lost to history. IRIS was the loser to Harvard University in a brief, bitter contest for State Department patronage at the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Among IRIS founders were Mancur Olson, who might have been recognized with a Nobel Prize had he lived long enough, and Thomas Schelling, who lived long enough to collect one. The director was Charles Cadwell, a lawyer with plenty of experience with deregulation. Mostly involved in articulating proposals for Russia was theorist Peter Murrell, who advocated a considerably more cautious approach to industrial privatization and nation-building than the so-called “shock therapy” approach that carried the day.

Murrell’s 1990 book, The Nature of Socialist Economies: Lessons from Eastern European Foreign Trade (Princeton), had the advantage of being closely related to ideas espoused by Hungarian economist Janos Kornai, another member of the Nobel nomination league who died without recognition. Murrell is more than ever worth reading today.

What might have happened if independent businessman H. Ross Perot had stayed out of the 1992 presidential race? Perot won 19 percent of the popular vote, enough to tip victory to the Democratic candidate, Bill Clinton. Had George H. W. Bush been re-elected, former Secretaries of State George Shultz and James Baker and National Security adviser Brent Scowcroft and their team would have directed U.S. policy towards Russia for the next four years. Talk about NATO expansion “not one inch east” might have become carefully qualified. Russia’s proposed “big bang” transition might have taken a different path. But Clinton won the presidency. He and his advisers had ideas of their own.

I followed Murrell for a time but became swept up in the excitement surrounding the incoming Clinton administration, among other matters. Would-be Harvard advisers to Russia seemed to be everywhere in those days. They included Kennedy School Dean Graham Allison and economists Marin Feldstein, Jeffrey Sachs and Andrei Shleifer. But it turned out that a 1989 conference in Moscow of the Soviet Academy of Sciences and the tripartite National Bureau of Economic Research from the U.S. had formed relationships that led to the deal. In 1992, Harvard’s Institute for International Development obtained a State Department contact to advise Yeltsin’s government.

Five years later the U.S. Department of Justice sued HIID, after Shleifer, a Russian expatriate, and his wife, hedge-fund manager Nancy Zimmerman, were caught trying to enter the Russian mutual-fund industry on their own. The government got its money back, and HIID was extinguished, just as was IRIS. A few years later I began Because They Could: The Harvard-Russia Scandal (and NATO Expansion) after Twenty-Five Years (2018, Create Space).

Next week, back to the grim present day.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

From order to chaos

“My Cup Runneth Over “(oil on aluminum panel), by West Newton, Mass.-based artist Marian Dioguardi, in her show “At the Edge of Seeing,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, through Oct. 7

She says: "When does ‘looking’ become ‘seeing’? In this series of observational paintings, I am asking ‘Where is that edge of observational order and where does it dissolve into visual chaos?’’’

Overwrought fears of a Providence bike trail

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The controversy over setting up a bike and walking lane (sometimes called an “urban trail”) in a commercially successful and charming stretch of Hope Street on Providence’s East Side has raised the inevitable issue of parking, which upsets some merchants and shoppers alike.

See:

The proposal would replace some of the street-side space now allocated to parked cars. Big parts of the fight come both from too many Americans’ unwillingness to walk more than a few feet from their cars to shop (and you can see the results in their physiques) and residential neighbors not wanting cars crowding nearby streets.

This gets me to think that the strip needs some sort of attractive (faced with brick or wood?) parking garage to take off some of the pressure.

Meanwhile, a big problem with bike lanes in some places is the failure of bicyclists to learn and obey basic traffic rules, e.g., signaling, and of police to enforce them. Time for Providence Police and other officials to work on that, including with signs and hefty fines!

Some of the local merchants want the city to call off a trial of the trail set for Oct. 1-8. No, the experiment should go forward! Let’s see how it unfolds and then either drop the idea or, if the project is to become permanent, adjust as needed. Of course, any change like this brings out Nimbyism and anxiety in people who have operated in a setting that has changed relatively little over the years.

But read what’s happened elsewhere.

https://thesource.metro.net/2017/11/20/biking-is-good-for-business/

https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/biking-lanes-business-health-1.5165954

https://medium.com/sidewalk-talk/the-latest-evidence-that-bike-lanes-are-good-for-business-f3a99cda9b80

Bicycle parking at the Alewife subway station, in Cambridge, Mass., at the intersection of three cycle paths.

— Photo by Arnold Reinhold

‘Not so awful as that elsewhere’

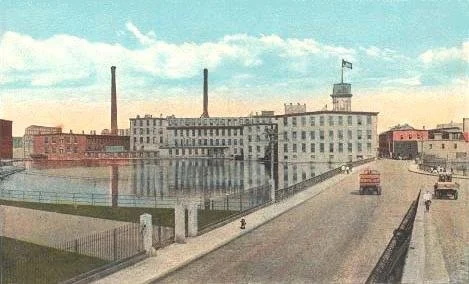

Factory scene in Fall River in 1920.

“I cannot praise some aspects of the Yankee city. Such ulcerous growths of industrial New England as Lowell, Lawrence, Lynn, Pawtucket, Woonsocket, and Chelsea seem the products of nightmare. To spend a day in Fall River is to realize how limited were the imaginations of poets who have described hell. It is only when one remembers Newark, Syracuse, Pittsburgh, West Philadelphia, Gary, Hammond, Akron, and South Bend that this leprosy seems tolerable. The refuse of industrialism knows no sectional boundaries and is common to all America. It could be soundly argued that the New England debris is not so awful as that elsewhere – not so hideous as upper New Jersey or so terrifying as the New South. It could be shown that the feeble efforts of society to cope with this disease are not so feeble here as elsewhere. But realism has a sounder knowledge: industrial leadership has passed from New England, and its disease will wane. Lowell will slide into the Merrimack, and the salt marsh will once more cover Lynn — or nearly so. They will recede; the unpolluted sea air will blow over them, and the Yankee nature will reclaim its own.’’

— From “New England: There She Stands,’’ by historian, essayist and editor Bernard De Voto (1897-1955) in the March 1932 Harper’s Magazine. The article, written during the Great Depression is a fair and very resonant paean to the region. It’s still well worth reading.

1905 postcard