Emmarie Hutteman: Heat waves pose particular dangers to young people

Children seeking relief in New York City in a July 1911 heat wave.

“Children are more vulnerable to climate change through how these climate shocks reshape the world in which they grow up.’’

Aaron Bernstein, M.D., pediatric hospitalist at Boston Children’s Hospital

After more than a week of record-breaking temperatures across much of the country, public health experts are cautioning that children are more susceptible to heat illness than adults are — even more so when they’re on the athletic field, living without air conditioning, or waiting in a parked car.

Cases of heat-related illness are rising with average air temperatures, and experts say almost half of those getting sick are children. The reason is twofold: Children’s bodies have more trouble regulating temperature than those of adults, and they rely on adults to help protect them from overheating.

Parents, coaches, and other caretakers, who can experience the same heat very differently than kids do, may struggle to identify a dangerous situation or catch the early symptoms of heat-related illness in children.

“Children are not little adults,” said Dr. Aaron Bernstein, a pediatric hospitalist at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Jan Null, a meteorologist in California, recalled being surprised at the effect of heat in a car. It was 86 degrees on a July afternoon more than two decades ago when an infant in San Jose was forgotten in a parked car and died of heatstroke.

Null said a reporter asked him after the death, “How hot could it have gotten in that car?”

Null’s research with two emergency doctors at Stanford University eventually produced a startling answer. Within an hour, the temperature in that car could have exceeded 120 degrees Fahrenheit. Their work revealed that a quick errand can be dangerous for a kid left behind in the car — even for less than 15 minutes, even with the windows cracked, and even on a mild day.

As record heat becomes more frequent, posing serious risks even to healthy adults, the number of cases of heat-related illnesses has gone up, including among children. Those most at risk are young children in parked vehicles and adolescents returning to school and participating in sports during the hottest days of the year.

More than 9,000 high school athletes are treated for heat-related illnesses every year.

Heat-related illnesses occur when exposure to high temperatures and humidity, which can be intensified by physical exertion, overwhelms the body’s ability to cool itself. Cases range from mild, like benign heat rashes in infants, to more serious, when the body’s core temperature increases. That can lead to life-threatening instances of heatstroke, diagnosed once the body temperature rises above 104 degrees, potentially causing organ failure.

Prevention is key. Experts emphasize that drinking plenty of water, avoiding the outdoors during the hot midday and afternoon hours, and taking it slow when adjusting to exercise are the most effective ways to avoid getting sick.

Children’s bodies take longer to increase sweat production and otherwise acclimatize in a warm environment than adults’ do, research shows. Young kids are also more susceptible to dehydration because a larger percentage of their body weight is water.

Infants and younger children also have more trouble regulating their body temperature, in part because they often don’t recognize when they should drink more water or remove clothing to cool down. A 1995 study showed that young children who spent 30 minutes in a 95-degree room saw their core temperatures rise significantly higher and faster than their mothers’ — even though they sweat more than adults do relative to their size.

Pediatricians advise caretakers to monitor how much water children consume and encourage them to drink before they ask for it. Thirst indicates the body is already dehydrated.

They should also dress kids in light-colored, lightweight clothes; limit outdoor time during the hottest hours; and look for ways to cool down, such as by visiting an air-conditioned place like a library, taking a cool bath, or going for a swim.

To address the risks to student athletes, the National Athletic Trainers’ Association recommends that high school athletes acclimatize by gradually building their activity over the course of two weeks when returning to their sport for a new season — including by slowly stepping up the amount of any protective equipment they wear.

“You’re gradually increasing that intensity over a week to two weeks so your body can get used to the heat,” said Kathy Dieringer, president of NATA.

Warning Signs and Solutions

Experts note a flushed face, fatigue, muscle cramps, headache, dizziness, vomiting, and a lot of sweating are among the symptoms of heat exhaustion, which can develop into heatstroke if untreated. Call a doctor if symptoms worsen, such as if the child seems disoriented or cannot drink.

Taking immediate steps to cool a child experiencing heat exhaustion or heatstroke is critical. The child should be taken to a shaded or cool area; be given cool fluids with salt, like sports drinks; and have any sweaty or heavy garments removed.

For adolescents, being submerged in an ice bath is the most effective way to cool the body, while younger children can be wrapped in cold, wet towels or misted with lukewarm water and placed in front of a fan.

Although children’s deaths in parked cars have been well documented, the tragic incidents continue to occur. According to federal statistics, 23 children died of vehicular heatstroke in 2021. Null, who collects his own data, said 13 children have died so far this year.

Caretakers should never leave children alone in a parked car, Null said. Take steps to prevent young children from entering the car themselves and becoming trapped, including locking the car while it’s parked at home.

More than half of cases of vehicular pediatric heatstroke occur because a caretaker accidentally left a child behind, he said. While in-car technology reminding adults to check their back seats has become more common, only a fraction of vehicles have it, requiring parents to come up with their own methods, like leaving a stuffed animal in the front seat.

The good news, Null said, is that simple behavioral changes can protect kids. “This is preventable in 100% of the cases,” he said.

A Lopsided Risk

People living in low-income areas fare worse when temperatures climb. Access to air conditioning, which includes the ability to afford the electricity bill, is a serious health concern.

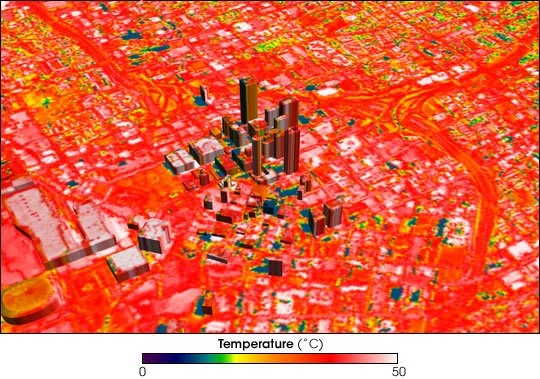

A study of heat in urban areas released last year showed that low-income neighborhoods and communities of color experience much higher temperatures than those of wealthier, white residents. In more impoverished areas during the summer, temperatures can be as much as 7 degrees Fahrenheit warmer.

The study’s authors said their findings in the United States reflect that “the legacy of redlining looms large,” referring to a federal housing policy that refused to insure mortgages in or near predominantly Black neighborhoods.

“These areas have less tree canopy, more streets, and higher building densities, meaning that in addition to their other racist outcomes, redlining policies directly codified into law existing disparity in urban land use and reinforced urban design choices that magnify urban heating into the present,” they concluded.

This month, Bernstein, who leads Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment, co-authored a commentary in JAMA arguing that advancing health equity is critical to action on climate change.

The center works with front-line health clinics to help their predominantly low-income patients respond to the health impacts of climate change. Federally backed clinics alone provide care to about 30 million Americans, including many children, he said.

Bernstein also recently led a nationwide study that found that from May through September, days with higher temperatures are associated with more visits to children’s hospital emergency rooms. Many visits were more directly linked to heat, although the study also pointed to how high temperatures can exacerbate existing health conditions like neurological disorders.

“Children are more vulnerable to climate change through how these climate shocks reshape the world in which they grow up,” Bernstein said.

Helping people better understand the health risks of extreme heat and how to protect themselves and their families are among the public health system’s major challenges, experts said.

The National Weather Service’s heat alert system is mainly based on the heat index, a measure of how hot it feels when relative humidity is factored in with air temperature.

But the alerts are not related to effects on health, said Kathy Baughman McLeod, director of the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center. By the time temperatures rise to the level that a weather alert is issued, many vulnerable people — like children, pregnant women, and the elderly — may already be experiencing heat exhaustion or heatstroke.

The center developed a new heat alert system, which is being tested in Seville, Spain, historically one of the hottest cities in Europe.

The system marries metrics like air temperature and humidity with public health data to categorize heat waves and, when they are serious enough, give them names — making it easier for people to understand heat as an environmental threat that requires prevention measures.

The categories are determined through a metric known as excess deaths, which compares how many people died on a day with the forecasted temperature versus an average day. That may help health officials understand how severe a heat wave is expected to be and make informed recommendations to the public based on risk factors like age or medical history.

The health-based alert system would also allow officials to target caretakers of children and seniors through school systems, preschools, and senior centers, Baughman McLeod said.

Giving people better ways to conceptualize heat is critical, she said.

“It’s not dramatic. It doesn’t rip the roof off of your house,” Baughman McLeod said. “It’s silent and invisible.”

Emmarie Huetteman is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Emmarie Huetteman: ehuetteman@kff.org, @emmarieDC

Float it with you

“Moat” (oil on stretched canvas), by Boston-based artist Eben Haines, in his show “In The Houses of Empire: Everything’s Fine,’’ at the Cory Daniels Gallery, Wells, Maine, Aug. 13-Sept. 17.

The gallery says:

“Haines’s works investigate the life of objects, emphasizing the constructed nature of history. Many works explore altered conventions of portraiture, through figures and objects pictured against cinematic backdrops or in otherworldly scenes. His paintings and installations employ various techniques and materials to suggest the passage of time and volatility, set within displaced domestic structures, critiquing the unbalanced systems we take for granted and overlook. Comets race across the skies of bucolic landscapes, Roman portrait busts stand in for the corrupting force of unchecked power. Candles appear to signal that time is running out, floating before cloaked figures whose identities remain circumspect. Recent works consider themes such as climate change and systemic housing insecurity before and during the pandemic, exploring the illusionistic systems meriting human rights like shelter, food, and healthcare to the privileged few.’’

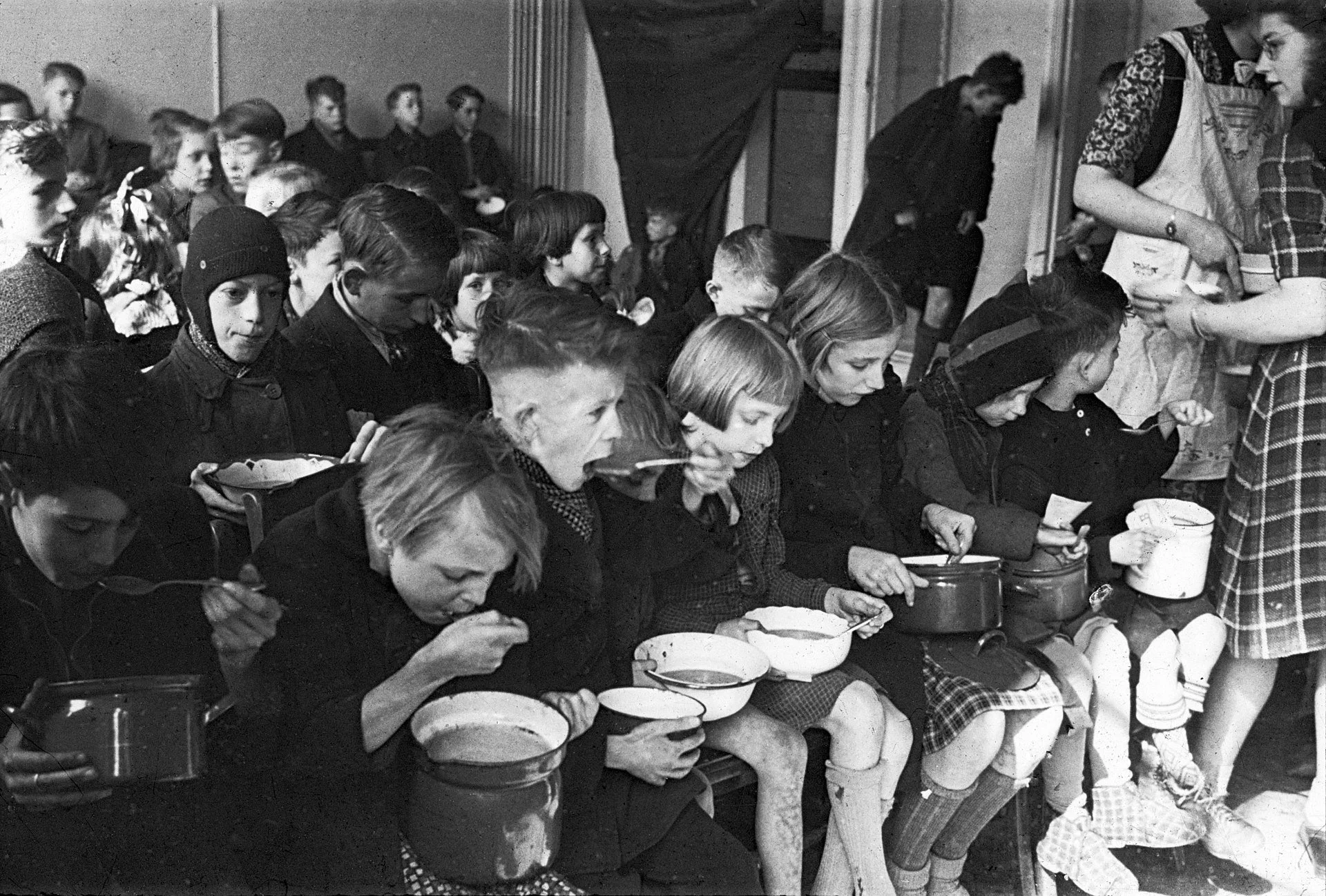

Llewellyn King: 'Hunger Winter' may loom amidst energy crisis caused by Putin

Dutch children eating soup during the famine of 1944–1945.

— Photo by Menno Huizinga

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Even as Europe has been dealing with its hottest summer on record, it has been fearfully aware that it may face its worst winter since the one at the end of World War II, from 1944 to 1945.

Electricity shortages and prices for fuel that are unpayable for many households are in store for Europe.

Industrial production in Germany, Europe’s economic driver, is threatened and governments from London to Athens are struggling with how they will help with energy bills right now, let alone in the dead of winter.

Electricity production on the European grid was already strained due to the change from coal and gas generation to renewables.

Germany worsened a tight supply by shutting down its nuclear plants, and the new reliance on wind was severely questioned by a wind drought last fall, especially in the North Sea.

After Vladimir’s Putin’s Russia attacked Ukraine with an all-out invasion on Feb. 24, things went from tightness of supply to impending disaster. Russia, through a complex network of pipelines, is the principal supplier of natural gas to Europe and all petroleum products to Germany. Now it has curtailed normal flows.

Europe is heavily dependent on gas for heating and for making electricity. As things stand, all of Europe is hurting, especially Germany. The country may suffer as dreadful a winter as it did at the end of World War II when there was no coal, the essential fuel at the time.

The unknowns revolve around Russia’s war in Ukraine. These are possible scenarios:

-- Russia wins outright; Europe continues sanctions and is punished with gas interruptions. Result: Europe freezes this winter.

-- There is a political settlement, the rebuilding of Ukraine begins and the gas flows again.

-- Ukraine repulses Russia on the ground; Russia changes regime and abandons the fight.

-- The conflict worsens, and NATO is drawn in. Europe rations fuel, including kerosene. It is a wartime footing for all of Europe.

-- Germany decides it has had enough and makes a deal with Russia. Ukraine figuratively is thrown under the bus.

While the United States and other gas-producing nations will export all they can to Europe in the form of liquified natural gas, those sources are already heavily committed. The United States, for example, has just seven LNG export terminals. These take years to license and build, and the same goes for the receiving terminals and LNG tankers. Additionally, most of the European receiving terminals are in the West and the severest shortages are in the East.

It is too late to change one certainty about the coming winter: high food prices everywhere, including in the United States, and starvation in developing countries. Ukraine is exporting grain haltingly, but those shipments are too small and too late. Afghanistan and Somalia are already in a food crisis, starting what is set to be a world run on grain provided in humanitarian relief.

The terrible European winter of 1944 to 1945 is known as the “Hunger Winter’’. Prepare to hear that term resurrected.

The world must brace for the coming winter in the Northern Hemisphere with political uncertainty and weak, inward-looking leaders in many countries. In the United States, the midterm elections are set to produce division. In France, President Emmanuel Macron has lost control of the National Assembly. Britain is seeking a new Tory prime minister to replace Boris Johnson. Italy is facing an election that some forecasts say will go to the isolationist fascists.

The democracies are riven with culture wars and other indulgences as a global crisis is in the making in Europe. For much of the rest of the world a new Hunger Winter looms. Many will be cold this winter, others will be hungry. Untold numbers will die.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Peter Certo: A small city mayor who did big stuff

William A. Collins

Via OtherWords.org

I learned this week about the passing of a remarkable man. Bill Collins died recently in a car accident at the age of 87.

Bill was a popular former mayor of Norwalk, Conn. In his hometown, tributes have poured in celebrating Bill’s legacy of revitalizing the city’s downtown, professionalizing its civil service, and championing affordable housing over his four terms in office.

But I got to know Bill because of the remarkable work he did after retiring from public service.

An aspiring journalist, Bill had lots of ideas — far too many for the odd assignment or op-ed. Instead, Bill enlisted foundations, public interest groups, well-known populist columnists like Jim Hightower and the late Donald Kaul, and small newspapers across the country to build a nonprofit opinion syndicate entirely from scratch.

Calling his project “Minuteman Media” after the pro-democracy partisans who launched the American Revolution, Bill anticipated some of the most dire threats to democracy in the U.S. today.

Even two decades ago, Bill saw how cost-cutting and contraction were making it harder for America’s hometown papers to cover all the issues that mattered to their readers. He saw how mediocre partisan sludge was poisoning political commentary. And he saw the horrid polarization that would follow if this bile filled the void left by community newspapers.

Over the years, BIll worked to head off that crisis by distributing thousands of free, high-quality opinion pieces — and his own weekly column — covering progressive perspectives and a wide variety of public interest causes. The network Bill launched reached deep into red and purple parts of the country, ensuring a lively exchange of ideas in a polarizing climate — and offering a valuable free resource to the cash-strapped local papers that are so vital for democracy.

Eventually, Bill handed the project over to the Institute for Policy Studies, which rebranded it “OtherWords” in 2009. He wanted to free up his time to travel, which he did with abandon. After spending his youth hitchhiking across the African continent, he spent his retirement criss-crossing dozens of countries — and taking long drives across North America, including a road trip to Alaska.

All the while, he kept churning out his weekly column, which I eventually got to edit.

It was remarkable — he’d file six or eight at a time. In any given batch, he’d write passionately about the need for a living wage, more affordable housing, and stronger labor protections. He’d expound on the need to protect the vote, expand civil rights, and end the war on drugs.

And again and again, as an Army veteran and a board member of Veterans for Peace, Bill would call to end our wars, take care of our veterans, and expose the ruthless profiteering of the military-industrial complex.

Then he’d head off for heaven knows where.

As the years went by, Bill traveled more and wrote less. But he’d still surface now again with a column — or some gruff advice. When I took over as the chief editor of OtherWords in 2016, he sent me his first note in probably two years: “JUST SAW YOUR HEADSHOT. COMB YOUR HAIR AND PUT ON A TIE.”

In his last column, published in 2019, Bill — then 84 or so — wrote about joining a peace delegation to Iran. He marveled at the warmth of ordinary Iranians and condemned what he called “our stupid sanctions” that “are hurting average people rather than their leaders” and making the United States look “like a jerk.”

Bill was a worldlier man than I’ll ever be, but it was that blunt, small-town decency that made him great.

It’s been the honor of my professional life to shepherd the syndication project he founded, which today makes thousands of op-ed placements each year. Our work appears in publications that regularly reach over 10 million print readers and upwards of 100 million digital readers — a great many of them in the small and medium-sized papers that still dot America’s heartland, just like Bill imagined.

Bill was a small-city mayor who traveled the world. An Army veteran who hated war. A fierce progressive who wrote tirelessly for conservatives. But whatever other title he held, Bill Collins filled the highest office in any democracy: the citizen. Rest in peace, Bill.

Peter Certo is the editorial manager of the Institute for Policy Studies and the editor of OtherWords.org, a nonprofit editorial syndicate launched as “Minuteman Media” by Bill Collins.

A state made for bad puns

“When they can hear each other over the wind and the music, they speak Connecticut: I will not Stamford this type of behavior. What's Groton into you? What did Danbury his Hartford? New Haven can wait. Darien't no place I'd rather I'd rather be.’’

— David Levithan (born 1972) (American fiction writer and editor)

Regulation upon regulation upon….

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocalProv.com

Department of Excess Regulations, Rule #17rwqdewew19:

Massachusetts has enacted a law banning discrimination based on a person's hair texture or style.

The sponsor of the bill that led to the law, Boston Democrat Lydia Edwards, the Senate's only Black member, said:

"You must understand what systemic racism does is not just prohibit economic opportunity and jobs. It diminishes the soul. It diminishes yourself of who you are because of something you cannot control. And it took me so long, so long, as a part of my life to ever say that my hair is long, that it is beautiful and that is natural."

The Age of Me continues….

One problem with this sort of micro-anti-discrimination law is that it can be used to protect people who might be about to be fired for other things than their hair, such as incompetence. And do we need to cite yet another personal characteristic as a basis for another law promoting hyper-sensitivity? And can we please edge away from a society of endless individual aggrievement?

Engagement with Vt. landscape

"The Sky is Falling" (mixed media and acrylic), by Boston area-based Anne Sargent Walker, in the group show “Drawn Togther,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, through Aug. 28.

Her Web site says:

“Anne’s semi-abstract paintings in oil and acrylic often combine fragments of vintage wall paper, painted birds, jumping men, and other images which explore our relationship to the natural world. Most recently Anne has been compelled to express her concerns over environmental issues. She attributes her interests in nature to childhood summers in Vermont with a naturalist father, and her continuing engagement with the rural Vermont landscape.’’

August wealth

Joe-Pye Weed

“August is ripening grain in the fields, vivid dahlias fling, huge tousled blossoms through gardens, and Joe- Pye weed dusts the meadow purple.”

– Jean Hersey (1919-2007) author of The Shape of a Year, focused on gardening at the home in exurban Weston, Conn., she shared with her husband, the famed novelist and journalist John Hersey (1914-1993)

The Onion Barn, in Weston, where community bulletins are posted.

Warming up nostalgia

Summer afternoon shadow and sun in Acushnet, on the Massachusetts South Coast.

— Photo by William Morgan

Inspiration from travel

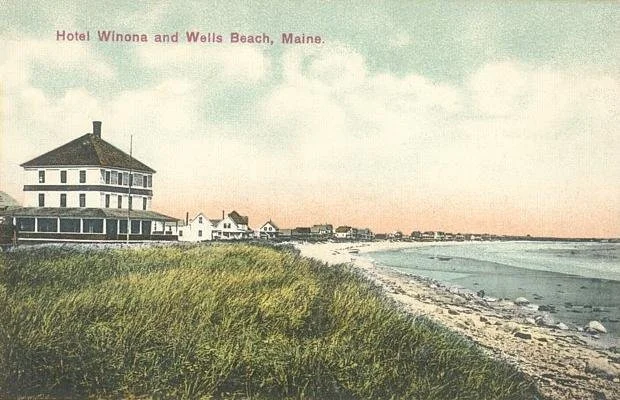

“Waterlilies” (encaustic, color pigments), by Jeanne M. Griffin, who is based in Wells, Maine.

Part of her artist statement:

“Travel plays a large role in my life and, over the years, I have visited close to 100 countries. I am particularly drawn to countries of the Third World and love seeking out and visiting with local artists. I have always been fascinated with their weavings and paintings and the textures and patterns they create using various tools and materials….”

“My travels expose me to many ideas and thoughts which percolate in my head and eventually find their way into my work. {For example} I have incorporated printing with Indonesian tjaps (more commonly used in batik printing) combined with encaustic medium and color pigments to produce each one-of-a-kind painting. This is one way of keeping my wonderful memories of these beautiful countries and interesting people alive.’’

Wells has long been a popular summer resort, as you can see in this 1908 postcard. Founded in 1643, it is the third-oldest town in Maine.

Tidal salt marsh at the Rachel Carson (1907-1964) National Wildlife Refuge, in Wells, named after the prolific writer, marine biologist and conservationist best know for the books Silent Spring and The Sea Around Us. She spent summers on the Maine Coast.

Quiet lope

— Photo by Airwolfhound

“As I followed my road,

the atmosphere altered

into a susurrus under the pines

and took shape in the lightfoot

lope of a rapt fox….’’

— From “Like No Other’’, by Peter Davison (1928-2004) Boston-based American poet, essayist, teacher, lecturer, editor and publisher

David Warsh: U.S. foreign policy, wars and global warming

American tanks in 1991 during the Gulf War.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

I have been dipping into Blood and Ruins: The Last Imperial War 1931-1945 (Viking 2021), by Richard Overy, of the University of Exeter, one of Britain’s foremost historians. The book is brilliant, difficult enough to pick up – 994 pages! – harder still to put down. I have been trying to understand why World War II ended the way it did.

World War II was the America’s first successful war of partition on the Eurasian continent: East and West Germany, the Iron Curtain, all that. A second successful war of seemingly permanent partition followed soon thereafter, in Korea.

The record since then hasn’t been good. America’s wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq all failed to achieve their aims. Now the U.S. is engaged in a proxy war with the Russian Federation, in defense of Ukraine. Meanwhile, China’s determination to take possession of Taiwan looms.

Partition failed in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq because American tactics were inept, borders were porous, enemy supply lines were short; and because the use of nuclear weapons, by now widely held, had become taboo.

What are the chances that the invasion of Ukraine will end in negotiated partition?

I don’t know anything more about the prospects for peace in the war in Ukraine than what I read in four major newspapers I follow. As a former newspaperman, for whom the war in Vietnam dominated most of a decade in my youth, I observe that coverage of the Russian invasion often is accompanied by the same overtones of moral outrage that were characteristic of the early stages of the wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq. The Financial Times seems the most consistently balanced of the leading English-language papers, admitting all viewpoints to its opinion pages, favoring none.

But even the FT seems uninterested for the most part in Russia’s side of the story. Vladimir Putin has been clear all along about his objections to NATO enlargement. But the 6,000-word essay he published a year ago, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” spelled out in some detail his version of NATO’s plans for Ukraine’s membership – and for the privatization of Ukraine’s economy.

I am as disgusted by the tradition of Russian disdain for legality, today in Ukraine, as I was in 1956, in Hungary; in 1968, in Czechoslovakia; in 1979, in Afghanistan. This Washington Post story – Russia wants Viktor Bout back, badly. The question is: Why? (subscription may be required) – is evidence that the tradition of lawless brutality has continued under Putin. But in a second-best world, when you routinely can’t get what you want, you must learn to get what you need.

For all this is unfolding against the backdrop of climate change. That story, too, I have been living with for most of my career as a journalist. In the last decade or two, the experience has come to be widely shared. The best metaphor for explicating global warming I know is the one associated with Michael Mann, of Penn State University, author, most recently, of The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet (Public Affairs, 2021).

Last week Mann told an interviewer for National Public Radio, “We frame this as if it’s some sort of cliff that we go off at three degrees Fahrenheit warming or four degrees Fahrenheit warming. That’s not what it is. It’s a minefield. And we’re walking farther and farther out onto that minefield. And the farther we walk out onto that minefield, the more danger that we are going to encounter.”

So back to Blood and Ruins. I cannot recommend Overy’s book highly enough. At the very beginning, he explains that he has taken his title from Imperialism and Civilization, a well-received 1929 book by Leonard Woolf, a political economist (and husband of the novelist Virginia Woolf). “Imperialism, as it was known in the nineteenth century, is no longer possible,” wrote Woolf, “and the only question is whether it will be buried peacefully or in blood and ruins.”

On the last page of his text, Overy concludes, “The Long Second World War… ended not only a particular form of empire, but discredited the longer history of the term.” He quoted the Oxford Africanist Margery Perham from a lecture in 1961 on what she believed had been a profound historical shift: “All though the sixty centuries of more or less recorded history, imperialism, the extension of political power by one state over another, was… taken for granted as part of the established order.”

Since 1945, however, she continued, the only authority that people would now accept “is that which arises from their own wills, or can be made to appear to do so.” Hence the scramble for the status of nationhood since the ‘50s, Overy wrote: There were193 sovereign countries, according to the United Nations, as of 2019.

Has the emergence of China as a hegemonic superpower and Putin’s determination to bundle together Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians in what he calls “a single triune nation,” changed all that? Probably it has. The pressing question now is whether the short-lived period of “the end of history” will conclude relatively peacefully, or enter a lengthy era of heat and ruins.

. xxx

A year ago, on the advice of a knowledgeable friend, I argued that Tunisians deserved a second chance to build a working system of government.

Tunisia had been celebrated as the only Arab nation to turn towards democratic rule since the “Arab Spring” of 201l sent autocrat Zine El Abidine Ben Ali into exile, after 20 years in power. A democratic constitution was adopted in 2014, but a series of coalition governments failed to solve the once-prosperous nation’s growing economic problems and religious strife. Law professor Kais Saied was elected in a landslide in 2019 and sent parliament home in July 2021 to rule by decree since then.

The draft of a new constitution, which, if adopted, would weaken term limits and extend presidential powers considerably, was endorsed by something like 92 percent of those who voted.

The trouble is, only 27.5 percent of eligible voters went to the polls, reflecting a boycott of the referendum by several leading parties. With food and energy prices rising, unemployment high, and tourism stagnant, the situation facing Saied does not seem promising.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

Global average temperature, shown by measurements from various sources, has increased since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

‘I fantasize a riot’

Food fight in Ivrea, Italy

— Photo by Giò - Borghetto Battle of Oranges - Battaglia delle Arance 2007 - Ivrea

“Dessert Is Counted Sweetest’’ (after Emily Dickinson poem. See below.)

(Appeared in the May/June 2022 Emily Dickinson International Society Bulletin)

Dessert is counted sweetest

By those who need to diet.

When doctors won't stop nagging,

I fantasize a riot.

Not one of all the cakes and pies

I might forgo today

Could fail to bring me pleasure --

Though later, much dismay.

— Felicia Nimue Ackerman is a Providence-based poet and Brown University philosophy professor.

The Dickinson poem:

Success is counted sweetest

By those who ne'er succeed.

To comprehend a nectar

Requires sorest need.

Not one of all the purple Host

Who took the Flag today

Can tell the definition

So clear of victory

As he defeated – dying –

On whose forbidden ear

The distant strains of triumph

Burst agonized and clear!

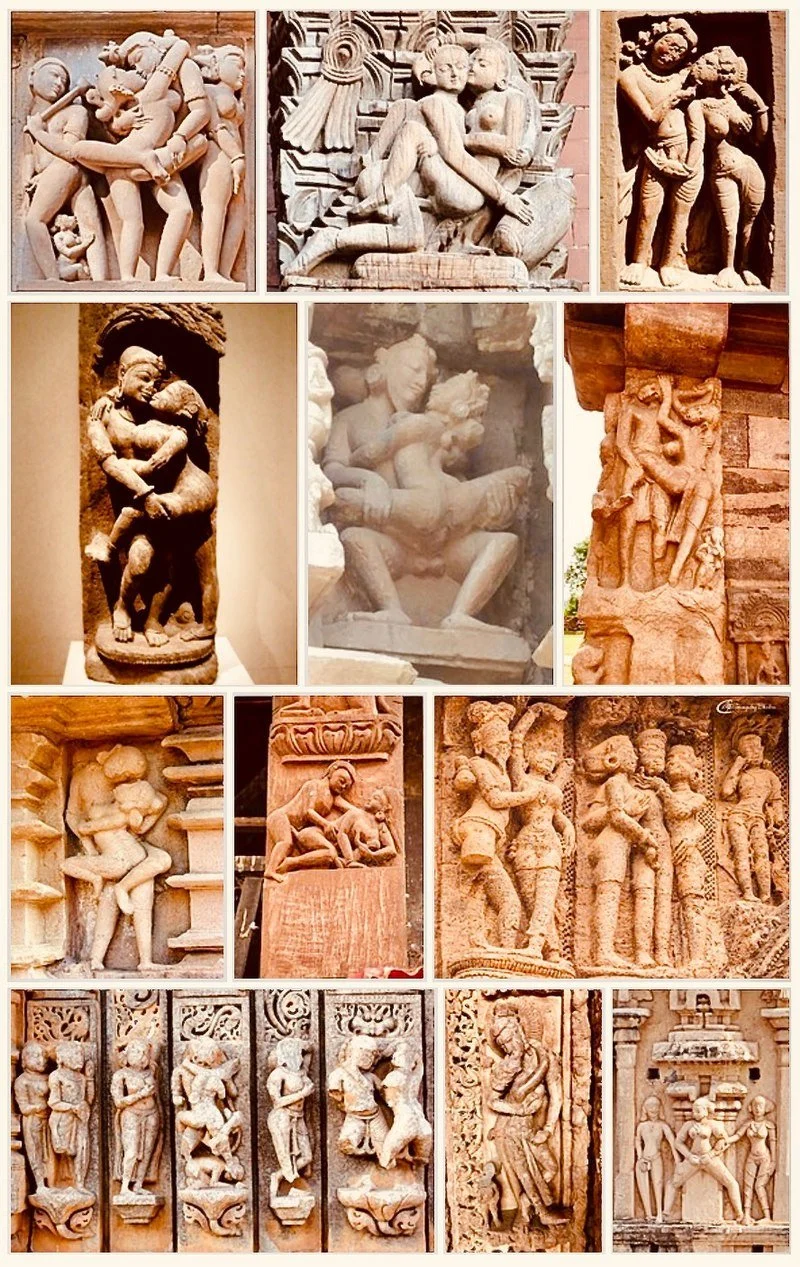

Faith and sex in New England

The Congregational Church of Middlebury, Vt.

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

— Photo by Ms Sarah Welch

“In New England, especially, [faith] is like sex. It's very personal. You don't bring it out and talk about it. “

— Carl Frederick Buechner (born 1926), American writer and Presbyterian minister. He lives in Vermont. He describes his area:

“Our house is on the eastern slope of Rupert Mountain, just off a country road, still unpaved then, and five miles from the nearest town ... Even at the most unpromising times of year – in mudtime, on bleak, snowless winter days – it is in so many unexpected ways beautiful that even after all this time I have never quite gotten used to it. I have seen other places equally beautiful in my time, but never, anywhere, have I seen one more so.’’

In Rupert, Vt.

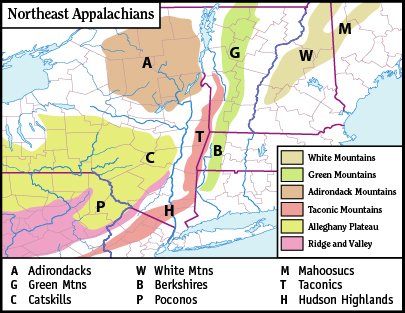

Ocean warming to continue to move lobster, scallop habitats

Lobsters awaiting purchase in Trenton, Maine.

— Photo by Billy Hathorn

An Atlantic Bay Scallop.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Researchers have projected significant changes in the habitat of commercially important American lobster and sea scallops along the Northeast continental shelf. They used a suite of models to estimate how species will react as waters warm. The researchers suggest that American lobster will move further offshore and sea scallops will shift to the north in the coming decades. {Editor’s note: New Bedford is by far the largest port for the sea-scallop fishery.}

The study’s findings were published recently in Diversity and Distributions. They pose fishery-management challenges as the changes can move stocks into and out of fixed management areas. Habitats within current management areas will also experience changes — some will show species increases, others decreases and others will experience no change.

“Changes in stock distribution affect where fish and shellfish can be caught and who has access to them over time,” said Vincent Saba, a fishery biologist in the Ecosystems Dynamics and Assessment Branch at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center and a co-author of the study. “American lobster and sea scallops are two of the most economically valuable single-species fisheries in the entire United States. They are also important to the economic and cultural well-being of coastal communities in the Northeast. Any changes to their distribution and abundance will have major impacts.”

Saba and colleagues used a group of species distribution models and a high-resolution global climate model. They projected the possible impact of climate change on suitable habitat for the two species in the large Northeast continental shelf marine ecosystem. This ecosystem includes waters of the Gulf of Maine, Georges Bank, the Mid-Atlantic Bight and off southern New England.

The high-resolution global-climate model generated projections of future ocean-bottom temperatures and salinity conditions across the ecosystem, and identified where suitable habitat would occur for the two species.

To reduce bias and uncertainty in the model projections, the team used nearshore and offshore fisheries independent trawl survey data to train the habitat models. Those data were collected on multiple surveys over a wide geographic area from 1984 to 2016. The model combined this information with historical temperature and salinity data. It also incorporated 80 years of projected bottom temperature and salinity changes in response to a high greenhouse-gas emissions scenario. That scenario has an annual 1 percent increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

American lobsters are large, mobile animals that migrate to find optimal biological and physical conditions. Sea scallops are bivalve mollusks that are largely sedentary, especially during their adult phase. Both species are affected by changes in water temperature, salinity, ocean currents and other oceanographic conditions.

Projected warming for the next 80 years showed deep areas in the Gulf of Maine becoming increasingly suitable lobster habitat. During the spring, western Long Island Sound and the area south of Rhode Island in the southern New England region showed habitat suitability. That suitability decreased in the fall. Warmer water in these southern areas has led to a significant decline in the lobster fishery in recent decades, according to NOAA Fisheries.

Sea-scallop distribution showed a clear northerly trend, with declining habitat suitability in the Mid-Atlantic Bight, southern New England and Georges Bank areas.

“This study suggests that ocean warming due to climate change will act as a likely stressor to the ecosystem’s southern lobster and sea-scallop fisheries and continues to drive further contraction of sea scallop and lobster habitats into the northern areas,” Saba said. “Our study only looked at ocean temperature and salinity, but other factors such as ocean acidification and changes in predation can also impact these species.”

Chris Powell: Conn. budget surplus the flip side of inflation

Price adjustment

— Photo by Jim.henderson

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut state government has had worse managers than Gov. Ned Lamont, but nobody should be much impressed by the huge financial surplus over which he is presiding -- more than $4 billion, equivalent to a fifth of state government's annual budget.

For the surplus is not a product of any astounding new efficiencies in state government achieved by the Lamont administration.

No, state government still spends more every year without any marked improvement in service to the public or the state's living standards.

Instead the surplus arises from billions of dollars in emergency cash from the federal government, distributed in the name of relief from the recent virus epidemic, and from big increases in state capital gains tax revenue.

Most state governments are enjoying big surpluses for the same reasons. But happy days are not really here again, for an old saying from Wall Street counsels caution: Don't mistake a bull market for genius.

Caution is especially advisable now because, on top of the termination of that emergency federal aid, the stock market has more often than not been falling for a few months and is no longer producing capital gains for people who, to get richer, had to do little more than hang around.

The capital gains on which they lately have been paying much more in state taxes are, along with all that federal money propping up the state's financial reserves, mainly the other side of the inflation that is devastating living standards throughout the country and the world.

The U.S. money supply, determined entirely by the federal government, is estimated to have increased by about 35 percent in the last three years even as the number of full-time workers fell, government paid people for not working, and production declined.

More money amid less production is the recipe for inflation, and perhaps not so coincidentally Connecticut state government's financial surplus of about 20 percent of the annual budget is closer to the real annual rate of inflation than the official rate misleadingly calculated by the government, which lately has been about 9 percent.

State government's financial position may look great but it has come at a great cost. Government has saved itself but not the people.

xxx

Connecticut's buzz word of the moment seems to be "equity." It sanitizes almost anything, including the state-licensed growing and retailing of marijuana. Under Connecticut's new marijuana-legalization program, licenses are to be required for large-scale growing of marijuana and to be limited to companies involving people from areas that saw a high level of prosecutions in the "war on drugs."

People who obeyed the drug laws will get no such privileges for their good citizenship.

In essence marijuana licenses are becoming political patronage. Meeting clear criteria won't be enough. The state Consumer Protection Department will award licenses not just according to the criteria but also as favoritism.

So it's not surprising that, as the Connecticut Examiner reported last week, a grower's license is likely to be awarded to a company owned in part by former state Sen. Art Linares, a Republican married to Stamford Mayor Caroline Simmons, a Democrat and former state representative.

That's called working both sides of the street.

According to the Examiner, the "equity" part of Linares's application is a partner who "has lived for five of the last 10 years in a disproportionately impacted area of Connecticut."

That is, a front man. How just and remedial!

All this evokes how Connecticut handled the start of cable television 50 years ago. State law divided the state into franchise areas with a single license to be issued for each. To qualify, a company had to be owned by local residents. But they weren't required to have the capital and expertise needed to operate the business.

So local politically connected people started such companies, got the franchise license, and sold the franchise to a real cable TV company, making a bundle. This racket came to be called "rent a citizen."

Today's marijuana-licensing racket will enrich people who need only to be friends with someone who can pretend to have been oppressed.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

And have an exciting night

“Push Your Beds Together’’ (acrylic, oil stick, pastel, spray paint and latex on canvas), by Brazilian artist Thai Mainhard, in her show at Lanoue Gallery, Boston, through Aug. 28.

The gallery says:

“Thai Mainhard’s abstract paintings combine expressive mark making with dense blocks of color to create complex and emotive compositions that navigate the space between chaos and calm. Her works draw inspiration from Abstract Expressionism, recalling the work of Willem de Kooning, Cy Twombly and Joan Mitchell. Mainhard works with a variety of media—including oil paint, oil sticks, spray paint, and charcoal—to create intuitive imagery that externalizes her feelings and personal experiences.’’

‘Small frightened faces’

Button of organization of white Boston residents (particularly from South Boston and Dorchester) opposed to court orders that mandated the busing of students to help desegregate the city’s public schools. Its initials, of course, were R.O.A.R.

“In 1974, when the City of Boston was desegregating its schools, I watched the news with my dad and saw the police escorts in riot gear, the protesters screaming at the buses, small frightened faces in their windows.’’

Wendell Pierce (born 1963), American actor and businessman. He’s a Black man.

Goes with the territory

“The roaring alongside he takes for granted,

and that every so often the world is bound to shake.

“He runs, he runs to the south, finical, awkward,

in a state of controlled panic, a student of Blake.’’

—From “Sandpiper,’’ by famed American poet Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979), who was born in Worcester and died in Boston. She lived in Brazil, among other places.

She spent parts of six summers (1974-1979) on the island town of North Haven Island, Maine, best known for its summer colony of prominent Northeasterners, particularly Boston Brahmins. Among the more notable summer residents was the painter Frank Weston Benson, who rented the Wooster Farm as a summer home and painted several canvases set on the island.

Harborfront and ferry terminal on the island of North Haven.

— Photo by Jp498

“Summer,’’ by Frank Weston Benson

Enjoying the heat, for a while

— Photo by Judson McCranie

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I love air conditioning, as I suspect most people do. We may be bankrupted by having so many cooling devices in our old house, but, hey, one is an environmentally friendly -- relatively! -- a heat pump. Of course, with most of our electricity still generated by fossil fuel, we help heat up the world with our air conditioners.

Still, from time to time, I look back fondly to those dog days of 60 years ago when we sat in a screened-in back porch with a cool slate floor reading and talking in a desultory way in the humid heat with the soft drone of the insects and the whisper of the southwest wind in the oak trees in the background. And how pleasant it was to bring our first (and surprisingly heavy) portable TV out to the porch so we could watch the likes of baseball, Perry Mason and political party conventions in the semi-outdoors, often with Popsicles slicking our hands, though my parents’ steady smoking reduced these pleasures a tad.

It was lovely, to a point, being languid. We lose something in being more and more cut off from the feel of the seasons. Now I’ll go back inside again from the front porch. Hot out here

Illustration of urban heat exposure via a temperature-distribution map: Blue shows (relativel) cool temperatures, red warm, and white hot areas.