‘Lost truly at last’

A section of Vermont’s Long Trail, which from the Massachusetts line to Quebec.

“I think I sought it. I think I

could not know myself un-

til I did not know where I was.

Then my self-knowledge con-

tinued for a while while I found

my way again in fear

and reluctance, lost truly at

last….’’

— From “Lost” (in the woods), by Hayden Carruth, an American poet and teacher who lived many years in the town of Johnson, in northern Vermont.

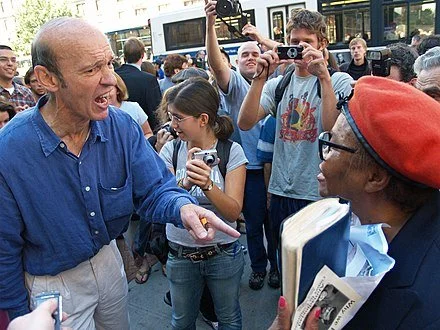

Cold or angry even in summer

— Photo by David Shankbone

South Boston

''This can be a cold place, Boston, and the weather is the least of it. We're often unwelcoming to outsiders. We have a maddening trait of sniping at insiders. We have equal parts determination and aloofness proudly bred into our native bones like the hunting instincts in championship dog.''

--Brian McGrory, in The Boston Globe of March 15, 2002

When he just trying to have fun

“They Thought He Was Dangerous” (mixed media on canvas), by Massachusetts artist and teacher Chandra Mendez-Ortiz, in the group show “The Long View: What Do You See (Do You See Me!),’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, June 29-July 31. The gallery says the show explores “a space where one reflects but imagines forward.’’

Trapped in a cycle

Tideline in Truro, Mass., on outer Cape Cod, where poet Alan Dugan lived.

Photo by Hqfrancis

“Water runs up the beach,

then wheels and slides

back down, leaving a ridge

Of sea-foam, weed, and shells….

One thinks: I must

break out of this

cycle of life and death….’’

-- From “The Sea Grinds Things Up,’’ by Alan Dugan (1923-2003)

Early evening at Head of the Meadow beach, North Truro

— Photo by Seduisant

The Truro Vineyards, in North Truro.

— Photo by Caliga10

David Warsh: The far right's successful fifty-year campaign to pack the Supreme Court

Better when empty? The interior of the U.S. Supreme Court.

— Photo Phil Roeder

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was the summer of 2005. George W. Bush had been re-elected president the autumn before. He possessed political capital, he exulted, and intended to use it. His inaugural address implicitly defended his invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and, without mentioning his embrace of NATO expansion, went further still: “[I]t is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.”

A popular uprising in Lebanon soon boiled over, was dubbed “the Cedar Revolution,” Syria agreed to end its thirty-year occupation of southern portion of the country, and Newsweek asked, on its cover, “Was Bush Right?”

But the war in Iraq remained bogged down. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice seemed to replace Vice President Dick Cheney as Bush’s closest foreign-policy adviser. The president’s major domestic initiative, a plan to privatize the Social Security System, on which Bush had campaigned since 1978, was abandoned. And in August, Hurricane Katrina flooded and flattened New Orleans.

Bush focused on the Supreme Court.

Sandra Day O’Connor announced her retirement a few months before. Eager to nominate the nation’s first Hispanic Supreme Court justice, Bush’s first choice was his friend and former White House counsel, Atty. Gen. Alberto Gonzales. Objections to his candidacy were raised, from anti-abortion conservatives in particular. So in July Bush nominated federal Appeals Court Judge John Roberts instead.

Within weeks, Chief Justice William Rehnquist died, after a lengthy battle with throat cancer. Bush re-nominated Roberts, this time to replace the chief, and to succeed O’Connor, he nominated another old friend, Harriet Miers, a corporate lawyer from Dallas, who had replaced Gonzalez as White House counsel. She was widely criticized for lack of judicial experience.

So, despite his determination to nominate a woman, Bush chose Samuel Alito instead.

In the 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama defeated John McCain. The next April, David Souter announced his retirement from the high court and Obama nominated federal Appeals Court Judge Sonia Sotomayor to succeed him. She was confirmed in August. Associate Justice John Paul Stevens retired the year after that, and though Obama was offered bipartisan support for the candidacy of federal prosecutor Merrick Garland, he nominated former Solicitor General Elena Kagan instead.

After Associate Justice Antonin Scalia died unexpectedly, in February 2016, Obama finally sent Garland’s name to the Senate to succeed Scalia, but even with seven months remaining before the November election, it was too late. Senate Majority Leader Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) refused to act on the nomination, and when Donald Trump was elected, it expired. During his term, Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett to replace Scalia, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Anthony Kennedy. McConnell got all three confirmed by the Senate.

It is not easy to pack the Supreme Court, but, working diligently, over a period of fifty years, a coalition of conservative lawyers, evangelical Christians and Catholic activists, had finally succeeded.

I was reminded of all this when I took down from the shelf The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: the Battle for the Control of the Law (Princeton, 2008), by Steven Teles, of Johns Hopkins University. Of particular salience was the early chapter on “The Rise of the Liberal Legal Network,” in which Teles describes as the conjunction of the Supreme Court led by Earl Warren and the development of an extensive supportive structure in law schools during the Rights Revolution of the 1950s and 1960s.

After that, this splendid book describes nearly everything you need to understand about the counter-mobilization that developed in the 1970s and 1980s: the advent of conservative public interest law in the early 1970s (and the early mistakes from which its institutions learned); the origins of the law and economics movement and its institutionalization by Henry Manne; the counter-networking since 1982 of the Federalist Society. There is a lot of history to imbibe in order to understand how the movement .achieved its most cherished goal last week.

On the other hand, if you want a glimpse of where the intermingling of law and economics is headed, read Republic of Beliefs: A New Approach to Law and Economics (Princeton, 2018), by Kaushik Basu, of Cornell University. Basu is a development economist, former chief economist of the World Bank (as were Paul Romer, Joseph Stiglitz and Anne Krueger), and, like them, a theorist; in his case, a student and collaborator of Amartya Sen and Anthony Atkinson. Basu expects focal points, a concept derived from game theory to play a central role in rethinking the relationship between economics and law. (Better, perhaps, to call it the study of interactive decision-making.)

What’s a focal point? You know one when you see one: shared manifestations of a psychological capacity, prevalent among humans, especially those who share common cultural backgrounds, which enables individuals to guess what others are likely to do, when faced with the problem of choosing from one among several possible options. A classic example? The decision whether to drive on the left or the right side of the road.

But that’s story for another day; a project for the next fifty years.

Meanwhile, if you are simply looking for the damaged but still-healthy roots of the mainstream Republican Party, the place to start is with Chief Justice Roberts’s opinion in the cases last week, in which he dissented from the “relentless freedom from doubt” displayed by his colleagues in their majority decisions last week:

The Court’s decision to overrule Roe and Casey {abortion cases} is a serious jolt to the legal system – regardless of how you view those cases. A narrower decision rejecting the misguided viability line would be markedly less unsettling, and nothing more is needed to decide this case.

George W. Bush’s original two preferences for the high court– Gonzales and Miers – surely would have concurred, had they been nominated and confirmed as associate justices. Roberts, it seems to me, had become the de facto leader of the old version of the Republican Party, U.S. Rep. Liz Cheney (R-Wyoming) its floor leader in Congress. If you want to know what will happen next, bide your time until autumn and carefully sift through the mid-term election results. Then fasten your seat belts for 2024.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Tangled up in empathy

“Three Models Legs and Hands” (watercolor,), by Donald C. Kelley, courtesy of The Artists Group of Charlestown (part of Boston). This is in the show “Donald C. Kelley: The Legacy Continues,’’ sponsored by The Artists Group of Charlestown, at the StoveFactory Gallery, Charlestown, through July 17.

Kelley (1928-2018) wrote in his artist statement: "Empathy lies at the heart of my figure drawings; I try to communicate directly through feeling ... when I am drawing or painting a representation of the body, I imagine myself within that body."

Site of Puritan leader/Boston founder John Winthrop's "Great House" in City Square, Charlestown, uncovered during the Big Dig. Archeologists said the building was occupied by Winthrop from July to October 1630. It was the Massachusetts Bay Colony's first government building, as well as Winthrop's dwelling before he moved to Boston.

Shoreline friend

“Favorite Dock #4, by Wendy Prellwitz, in her joint show with Sue Charles, “Down to Earth and Out to Sea,’’ at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

Philip K. Howard: Our governing processes have become paralytic, and what to do about it.

The Bayonne Bridge, where an urgently needed improvement has been blocked by inane regulatory red tape.

Crook Point Bascule Bridge (1908), once connecting Providence and East Providence, R.I. It’s been stuck in upright position since 1976.

— Photo by Matthew Ward

Governing is not a process of perfection. Like other human activities, governing involves tradeoffs and trial and error. One of the most important tradeoffs involves timing. Delay in governing often means failure. Nowhere is this more true than with environmental reviews for infrastructure. Every year of delay for new power lines, modernized ports, congestion pricing for city traffic and road bottlenecks means more pollution and inefficiency.

New York Times columnist Ezra Klein has awakened liberal readers to the reality, hiding in plain sight, that governing processes are paralytic: “The problem isn’t government. It’s our government. … It has been made inefficient.”

The other week columnist George Will asked whether America “can do big things again.” Citing our work, and the absurd 20,000-page review for raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge, which connects Bayonne, N.J., with New York City’s Staten Island, to permit new post-panamax ships into Newark Harbor, Will calls out “the progressive aspiration to reduce government to the mechanical implementation of an ever-thickening web of regulations that leaves no room...for judgment.” American Enterprise Institute scholar and Washington Examiner columnist Michael Barone, also citing our work, the other day called for a rebooting of government to “sweep out the ossified cobwebs.”

The recent $1.2 trillion federal infrastructure law contains tools to streamline permitting, including presumptive 200-page limits on environmental reviews and two-year processes that we championed. But actually giving permits requires officials to use their judgment about priorities and tradeoffs, not to overturn every pebble. That may be a problem in current bureaucratic culture. In a letter to the editor of The Washington Post, an environmental official objects to my suggestion that raising the roadway of the Bayonne Bridge using existing foundations “involved no serious environmental impact.” He asserts that “bringing larger, more polluting ships and increased cargo” to the port “would result in increased diesel pollution from both the ships and the trucks transporting the cargo.”

Actually, the new larger ships are much cleaner, pollution-wise and burn much less diesel fuel per container. That’s a reason they’re more efficient. Increasing the capacity of the Newark port will indeed result in more truck traffic, but those containers have to come in somewhere.

You start to see the problem. It’s impossible to talk about environmental impact in the abstract. What’s needed is a governing culture that can make judgments about practical tradeoffs.

In a piece for Fortune on efforts to protect kids online, Jonathan Haidt and Beeban Kidron cite my work on the benefits of a principles-based approach to writing laws.

Julia Steiny in the Providence Journal cites my work in describing how Providence public schools are being crushed by law: “The system suffers from what author Philip Howard calls The Rule of Nobody. He says that the law operates ‘not as a framework that enhances free choice but as an instruction manual that replaces free choice.’”

For the American Spectator, E. Donald Elliott provides a history of Common Good’s effort to bring about infrastructure permitting reform.

Philip. K. Howard is a New York-based lawyer, civic and cultural leader, author and photographer. He’s chairman of the legal- and regulatory-reform organization Common Good (commongood.org) and the author of, among other books, The Death of Common Sense and The Rule of Nobody.

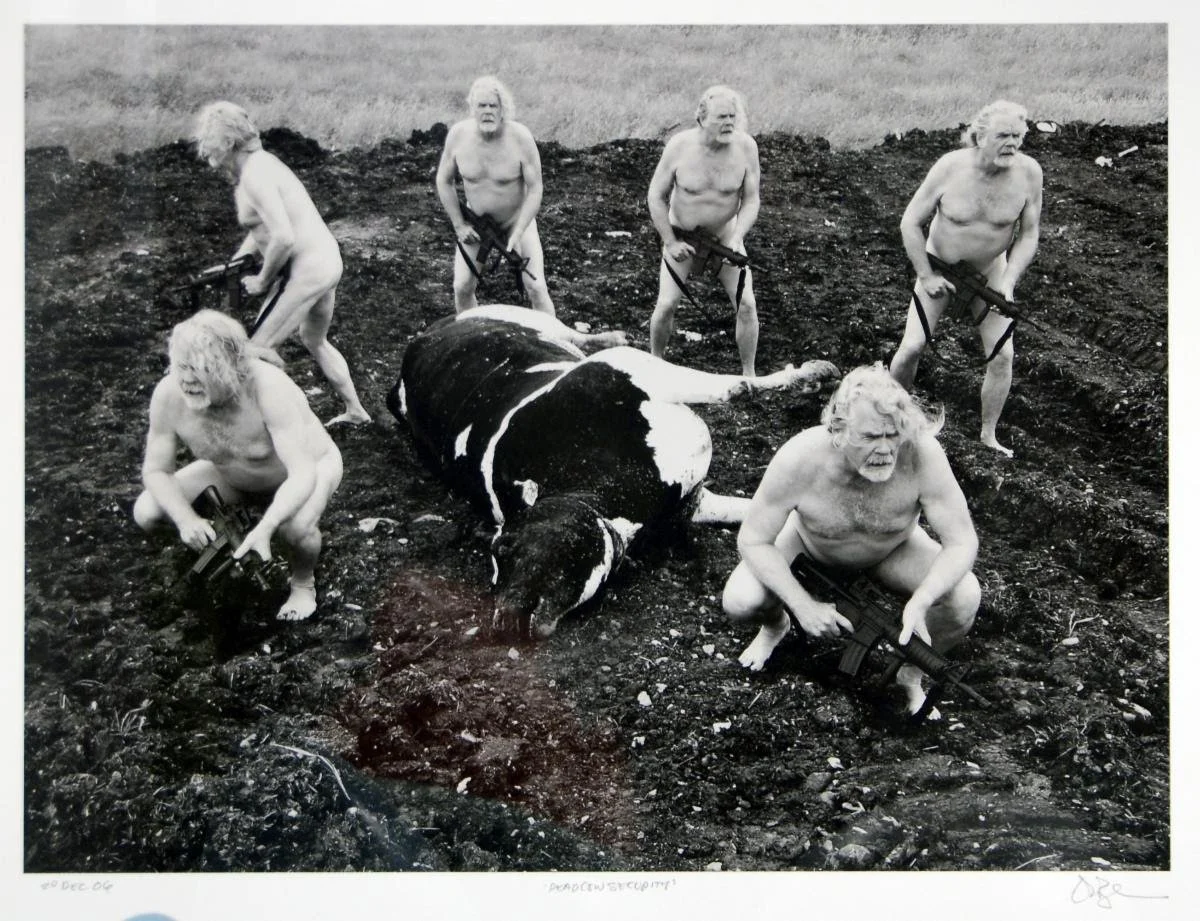

Protecting the pasture

“Cow Security: Homeland Security Series’’ (digital photographic composite), by John Douglas, in the show “John Douglas: A Life Well Lived,’’ at the Gallery@The Karma Bird House, connected with the Northern New England Museum of Art, Burlington, Vt., through Aug 22. (Photo courtesy of Eleanor “Bobbie” Lanahan).

The museum says:

“John Douglas’s memorial retrospective documents his long, productive, and substantive body of work. Douglas called himself a ‘truth activist.’ His irreverent, activist beliefs, and Zen-like appreciation of the world fueled his decades of creative output. Douglas unceasingly addressed injustice, hypocrisy, unjust wars, and climate change. In ‘Homeland Security' he leverages American symbols and uses himself as a central actor with near complete humility to create a forceful critique of our cultural priorities.’’

ECHO, Leahy Center for Lake Champlain, formerly the Lake Champlain Basin Science Center, is an science and nature museum on the Burlington waterfront of Lake Champlain. It hosts more than 70 species of fish, amphibians, reptiles and invertebrates, major traveling exhibitions and the Northfield Savings Bank 3D Theater. It’s named for U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy, of Vermont, who has long promoted the protection of the Lake Champlain Basin.

‘Our naked frailty’

“In June, amid the golden fields,

I saw a groundhog lying dead.

Dead lay he; my senses shook,

And mind outshot our naked frailty.’’

— From “The Groundhog,’’ by Richard Eberhart (1904-2005), American poet and Dartmouth College professor. He spent most of his post World War II time in New Hampshire and on the Maine Coast.

Earth to earth, sort of

In Mount Auburn Cemetery, near Boston.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“If this is dying then I don’t think much of it.’’

-- Lytton Stratchey (1880-1932), English writer

I enjoy walking through most graveyards, of which New England has many beauties. Wandering around gorgeous garden cemeteries, such as Swan Point, on the East Side of Providence, and Mt. Auburn, on the Watertown-Cambridge, Mass., line, can be soothing, even amidst the memento mori. Actually, giving yourself frequent reminders of death can be healthy: It’s focusing!

But many cemeteries are running out of space because people keep dying – very thoughtless of them. One of the challenges is that many families still want their loved ones’ corpses preserved with chemicals and put into coffins in burial vaults or at least concrete-lined, which take up a lot of room for a very long time. I think that’s related to survivors’ varying levels of denial of death. There’s this (to me) weird idea that somehow preserving that organic, decaying thing called a dead body fends off the person’s annihilation. (I see the decay and disappearance of the body as simply its return to what we all came from – ultimately space dust. Call it recycling.) But I realize, as a former churchgoer, that Christians are told to believe in the resurrection of the body.

Cremation is much better than standard burials, though it requires burning natural gas. Take your loved ones’ ashes home with you in a bag and put them in a vase; they won’t mind. Then in a few or many years, someone will probably forget where that vase is, or even whose ashes are in it.

Then there are the environmentally admirable decisions to compost the remains or use hydrolysis to reduce remains to their elements. A gift to Nature. Yes, this goes against some folks’ feeling that the dead body still contains some supernatural life – a feeling that’s been very profitable for the funeral/burial industry.

Llewellyn King: Prepare for a messy electric revolution

An experimental Firefly electric helicopter, developed by famed Sikorsky Aircraft, based in Stratford, Conn.

In 2016, Solar Impulse 2 was the first solar-powered electric aircraft to complete a circumnavigation of the world.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The 21st Century is set to be The Electric Century. We are in the middle of a profound electrification binge that will leave its mark on every aspect of human endeavor.

I believed this before I attended the Edison Electric Institute annual meeting and convention in Orlando. Now I believe it more than ever. The institute is the trade association of the investor-owned utilities.

Civilization already has been running on electricity, but it will do so in a more complete way in future. In simple terms, what will happen is what hasn’t been electrified will be electrified. Manufacturing, mining, farming and the processing of everything, from grains to making concrete, will be electrified.

The first big shift -- the one we can all see and participate in -- is the electrification of transportation, total electrification. That will include aircraft in time, but light aircraft are already in the experimental phase.

You can see it with the plethora of electric vehicles coming to market from old marques but, more exciting, from new companies making everything from huge tractor-trailer trucks to snazzy new pickups and sedans.

Three of these were among a lineup of all-electric vehicles on display outside the JW Marriott, Grand Lakes, Orlando hotel:

· 2022 Lucid Air: A stunning beautiful sedan, and the MotorTrend Car of the Year, with an impressive range of 530 miles, and an equally impressive price of about $139,000.

· Rivian pickup: One of a range of all-electric pickup trucks; this one designed for lighter loads, but still boasting a towing capacity of 11,000 pounds.

· Freightliner eCascadia: A semi-truck with a load capacity of 82,000 pounds, but a range of only 230 miles.

The significant thing here is the number of new manufacturers. These mean new ideas, new visions, new materials, and new horizons.

Each huge advance in transportation has required new entrepreneurs -- otherwise, the car companies would have built the aircraft. It wasn’t Chrysler, General Motors and Ford that rose into the skies, but new names like Boeing, Douglas and Sikorsky.

Ultimately markets will decide, and markets aren’t welfare organizations. They are cruel judges and executioners as well as supremely generous patrons.

The driver for this revolution is climate change. Twenty years ago, you could still with some credibility debate its reality. Today, the evidence is in every weather forecast. Things are getting hotter and, as any science student will tell you, when stuff heats up, things happen.

The utility industry has embraced the rationale of change to modify and one day reverse climate change through curbing the volume of greenhouse gases going into the air. It starts with their own generation, and soon will embrace all the carbon that spews from boilers and tailpipes.

Revolutions are messy things. Once underway they get a life of their own. There is confusion and mistakes are made at the barricades. But once underway, they can’t be turned back; yesterday can’t be summoned rule tomorrow.

The utilities I spoke to feel they will be able to meet the new electric load demand with a mixture of leveling out the power from intermittent renewables. This is called DSM (demand side management) and uses data from smart-metering to manage the demand in collaboration with their customers. For example, incentivizing commercial firms to agree to shut down some operations during peak demand, and even to enter into agreements with homeowners to operate dishwashers and other appliances late at night.

Then there is using the transport fleet as a big battery. The theory is your new electric vehicle can feed back into the grid as needed when it is fully charged. But there are those who doubt that this will be enough to bridge the gap between generation and future demand. Andres Carvallo, one of the fathers of the smart grid, and a polymath who runs numbers on the future from his perch at Texas State University and his company, CMG Consulting, believes a lot more actual generation will be needed to meet the growth in electrification.

Presumably, much of this would come from the new small modular reactors. Here is a paradox. Utility executives say, to a person, that nuclear is needed, but none say how it will be bought, sited and built. When nuclear is talked up by utilities these days, there is a dream quality about it.

The great goal of the industry, or the revolution if you will, is zero emissions by mid-century. All embrace the electrification surge. Many utilities have plans to eliminate their own emissions, but none is ready for a huge, nationwide surge in demand, nor is there a national plan to deal with pressing impediments like a lack of transmission.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Wiscasset aglow; Castle Tucker

“Tucker Hill View,’’ by Anthony Watkins, in Maine Art Gallery Wiscasset’s “Paint Wiscasset & Plein Air Show’,’ June 29-July 9.

The rather bizarre “Castle Tucker,’’ in Wiscasset. Judge Silas Lee built this Regency-style mansion in 1807 at the peak of Wiscasset's prosperity, when the town was one of New England’s busiest and richest ports, especially for lumber and fishing, as well as a major shipbuilding center. Lee's death, in 1814, combined with the cumulative financial impact of President Jefferson's Embargo of 1807, forced his widow to sell it. The house then passed through several owners hands until 1858, when Captain Richard H. Tucker Jr. , of a Wiscasset shipping family, bought the property. The Tucker family soon updated the interiors and added a new Italianate entrance and then a dramatic two-story porch to what had been the front of the house facing the Sheepscot River.

Looking out from Castle Tucker toward the Sheepscot River.

‘Not particularly pleasant’

Houses on Louisburg Square, on Beacon Hill, Boston

— Photo by Ajay Suresh

“Nothing which is worth while is easy, nor in my experience is the actual doing of it particularly pleasant. The pleasure arises from completion and from the knowledge that one has done the right thing and has stood by one’s convictions.’'

From John P. Marquand’s (1893-1960) The Late George Apley, Marquand’s brilliant satirical novel about upper-crust Boston

Where's my tip?

“Seraphim” (detail), by Bryony Bensley, in the group show “Connectivity,’’ at the Attleboro (Mass.) Arts Museum, through July 13.

Capron Park, in Attleboro, a former manufacturing city and now mostly a Boston and Providence suburb.

— Photo by Joey Kleinowskis

Chris Powell: Songs about Conn. (See video); enjoy its beautiful summer in spite of ….

Connecticut state seal. Note the grapes. The state has some fine vineyards.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

His innocent enthusiasms sometimes get the better of Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont, so a few weeks ago he celebrated a new country song purportedly about Connecticut by the musical impresario Rusty Gear. But the song's only lines about the state were not really so complimentary, and criticism by the governor's Republican challenger, Bob Stefanowski, made them a bit infamous:

Back home we thank the governor

For the blessings that we got.

We can gamble on the Internet

And it's cool to smoke some pot.

Of course, these days you can gamble on the Internet and smoke marijuana in most states without getting in trouble with the law, and if such activities really are to be considered great achievements, the country's decline becomes easier to explain.

Clever and catchy as it may be, the new song also can be criticized for historical and artistic inaccuracy. "Songs about my state are hard to find," Gear sings, suggesting that this is because not much rhymes with "Connecticut." (Gear makes do with "etiquette.") But there are at least nine other songs about or involving Connecticut, and of course you don't need to rhyme it to sing about it. You can rhyme other lyrics.

What may be the best of the Connecticut songs was recorded in 1945 by Bing Crosby and Judy Garland. It includes many references particular to the state, as well as gratuitous cracks at two other states. Crosby and Garland conclude:

Circled the globe dozens of times.

Seen all its wonders, known all its climes.

I've searched it with a fine-toothed comb

And found that I only have one home, sweet home.

Connecticut always will be my home.

Hit this link to hear the song.

Back then nobody needed Internet gambling and marijuana to extol the state. Instead Crosby and Garland celebrated it for being "peaceful and fair" and having "village greens," "childhood scenes," "moonlit streams" and "nights full of stars."

Perhaps a bit daring for the times, they added, "You'll find the chicks slicker" and "Every Yale guy is a male guy through and through."

Of course this was 77 years ago, before new sexual manifestations were discovered, and besides, hard as it is to rhyme "Connecticut," try rhyming something with "LGBTQ+."

The important things here are appreciation of what one has and the patriotism it should evoke despite its failings -- even as Connecticut has many failings, especially now that anyone pursuing the "peaceful and fair" in Hartford, New Haven and Bridgeport is just as likely to find gunshots, squalor, child neglect, despair, drug addiction, and depravity. Rhymes for those are more easily found.

But trouble like that did not discourage the philosopher, theologian and writer G.K. Chesterton.

"The world," Chesterton wrote a century ago, "is not a lodging-house at Brighton, which we are to leave because it is miserable. It is the fortress of our family, with the flag flying on the turret, and the more miserable it is, the less we should leave it.

“The point is not that this world is too sad to love or too glad not to love. The point is that when you do love a thing, its gladness is a reason for loving it, and its sadness a reason for loving it more.”

Hartford, Connecticut's capital city, was once thought to be the richest city in the country but now is among the poorest.

Bridgeport, once the state's manufacturing center, is not only desperately poor but pockmarked with the empty and crumbling factory buildings of its former fame.

Almost as poor is New Haven, which, once a pinnacle of scholarship, now produces instead much of the country's political correctness.

Nevertheless it is June and for a few months ahead government-addled Connecticut will be, in its natural condition, just as Crosby and Garland sang, probably the most beautiful place in the world, quite without gambling on the Internet and dope-smoking.

Hartford's Latin motto is "Post nubila phoebus" -- "After the clouds, the sun." As Chesterton envisioned, enough love, loyalty, effort and courage may vindicate that motto yet.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

‘Who knows how he got in’

The Boston Athenaeum

“Closing time at the Athenaeum,

but this visitor bat

(who knows how he got in)

seems intent on staying the night;

our waving arms, a rolled Times,

the janitor’s broom haven’t phased him a bit.’’

— From “American Sublime’’, by Mark Doty (born 1953)

The St. Johnsbury (Vt.) Athenaeum

— Photo by Gopats92

Summer in the mountains

On the Franconia Ridge, a section of the Appalachian Trail in the White Mountains.

— Photo by Paulbalegend

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

New Englanders tend to think more about heading toward the crowded seashore than to the mountains in the summer. I prefer the latter.

While I probably shouldn’t do it now (heart disease), I loved climbing in the White Mountains. They aren’t very high as mountains go – the highest, Mt. Washington, rises to only 6,288 feet above sea level -- but they have grandeur, in part because they have above-the-tree-line acreage, which affords climbers great views, though I read that with global warming the tree line is rising. And in the quasi-tundra above 4,500 feet, there are interesting plants, including delicate flowers otherwise only found in the Arctic.

Another joy of climbing is the camaraderie of fellow climbers, always happy to chat and provide advice: “That way is easier”. “Incredible views around that huge boulder.” “Watch out! It’s slippery!’’ “See the eagle!” And if you use the Appalachian Mountain Club’s “huts’’ to stop and have lunch or spend the night, you might strike up friendships with fellow hikers, many of whom come from far away. Some even bring along a bottle of wine to add to the festivities; they’re often Quebecois. People usually seem friendlier on mountains, at least in my experience.

You see some pretty strange things up there and not just such phenomena as weirdly and colorfully lit cloud formations.

Black flies are a particular menace in the late spring in northern New England. Years ago, a friend of mine and I spotted an older gent who looked familiar coming along the ridge of the Franconia Range. But the guy we knew had white hair. This man’s was red. Then we discovered that his hair was red from the blood from fly bites.

Also strange is some folks’ ridiculous outfitting, such as those who wear sneakers instead of proper hiking footwear. They usually deeply regret the sneakers, even if they don’t suffer a bad fall or sprained ankle as a result of wearing them.

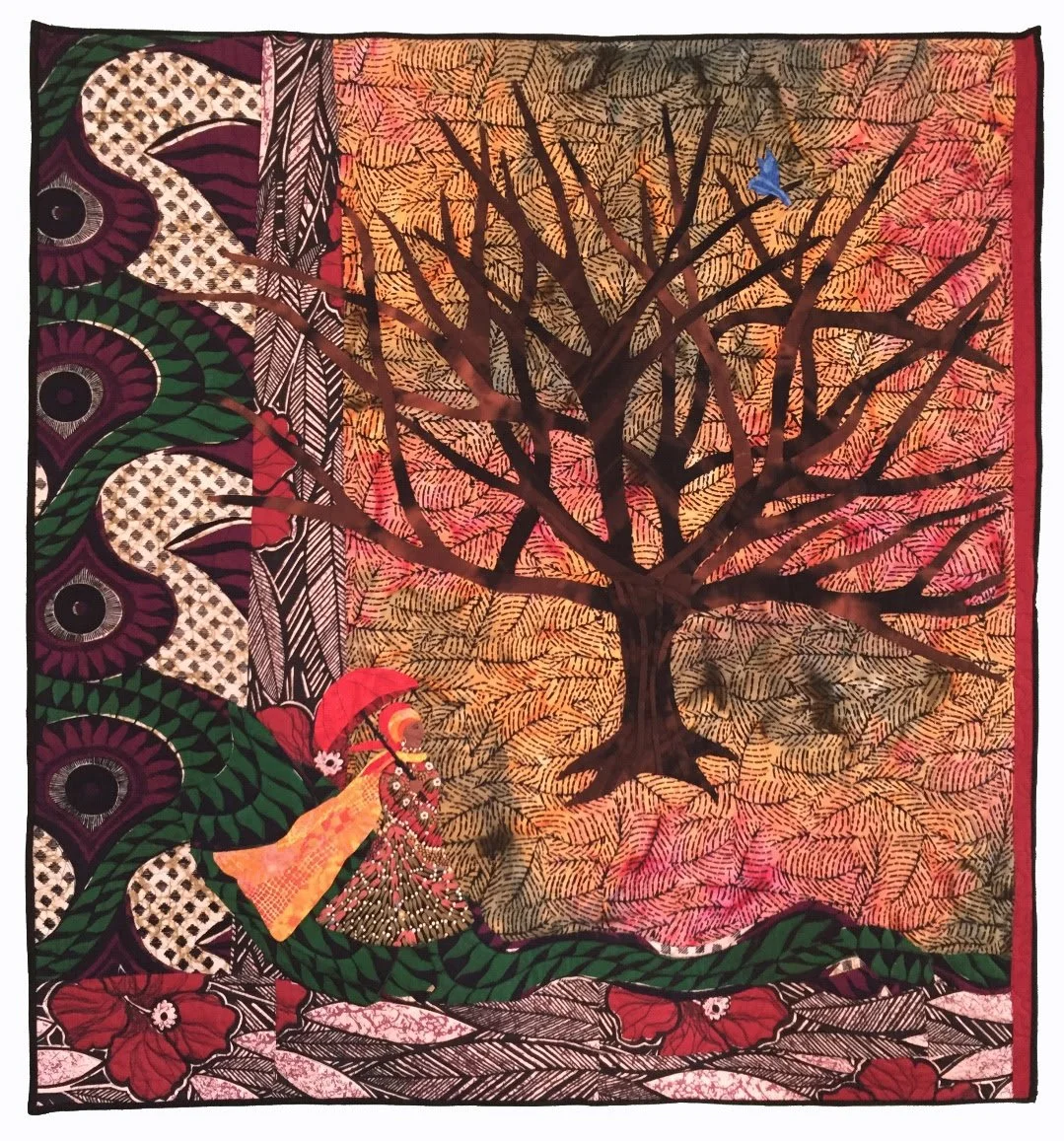

Quilted homecoming

Going Home II (quilt), by Doris Prouty (1947-2020) (Collection of the Prouty Family), in her posthumous show in “Her Mind’s Eye.’’ at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, through July 31.

The museum says:

“Working in vibrant colors and incorporating an array of shapes and patterns, Prouty’s quilts are founded in the traditions of African quilt makers and vividly capture scenes and stories about her life and community on Cape Ann. Beginning in the 1980s with traditional block patterns, Prouty moved on to appliqued quilts with pictures.’’