Victoria Knight: Sanders tries gambit to allow pharmaceutical imports from Canada and U.K.

The Haskell Free Library and Opera House straddles the border in Derby Line, Vt., and Stanstead, Quebec.

Harmony is not often found between two of the most boisterous senators on Capitol Hill, Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rand Paul (R-Ky.).

But it was there at June 14 Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee markup of legislation to reauthorize the Food and Drug Administration’s user fee program, which is set to expire Sept. 30.

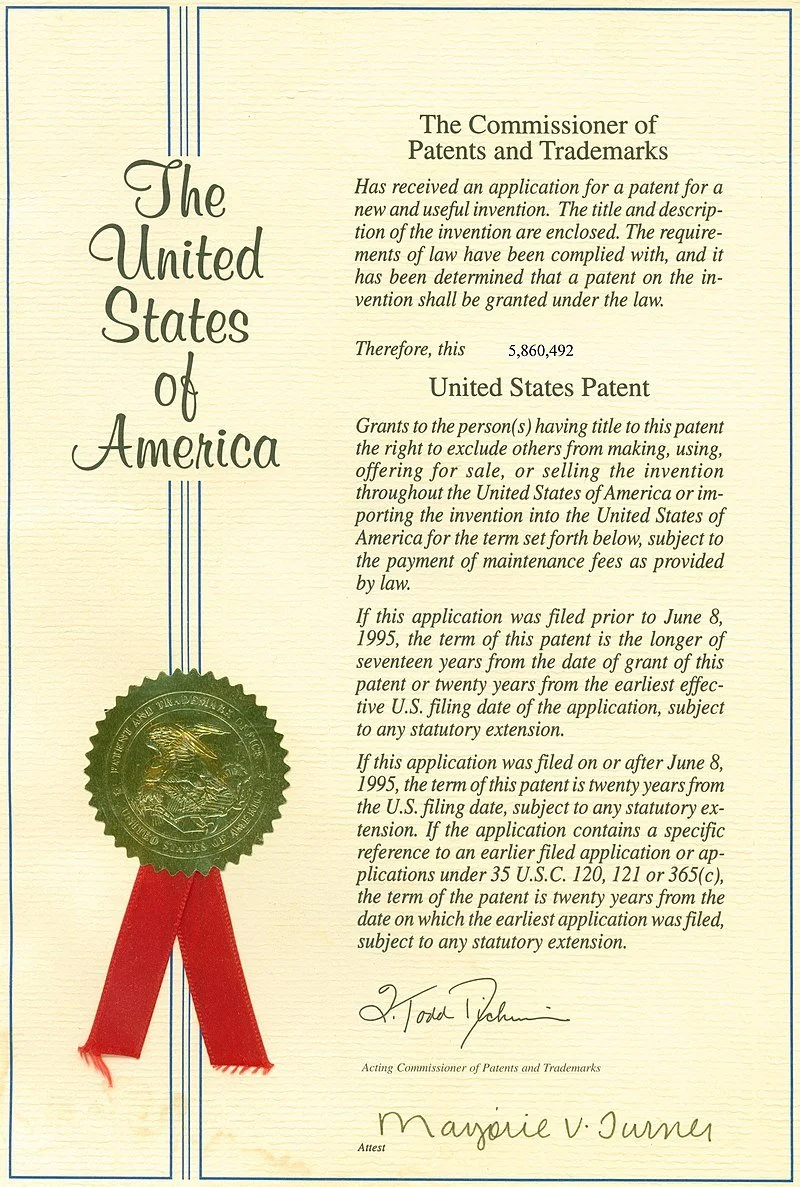

This user fee program, which was first authorized in 1992, allows the FDA to collect fees from companies that submit applications for drug approval. It was designed to speed the approval review process. And it requires reauthorization every five years.

Congress considers this bill a must-pass piece of legislation because it’s used to help fund the FDA, as well as revamp existing policies. As a result, it also functions as a vehicle for other proposals to reach the president’s desk — especially those that couldn’t get there on their own.

And that’s why, on that day Sanders took advantage of the must-pass moment to propose an amendment to the user fee bill that would allow for the importation of drugs from Canada and the United Kingdom, and, after two years, from other countries.

Prescription medications are often much less expensive in other countries, and surveys show that millions of Americans have bought drugs from overseas — even though doing so is technically illegal.

“We have talked about reimportation for a zillion years,” said a visibly heated Sanders. “This bill actually does it. It doesn’t wait for somebody in the bureaucracy to make it happen. It actually makes it happen.” He then went on for several minutes, his tone escalating, citing statistics about high drug prices, recounting anecdotes of people who traveled for drugs, and ending with outrage about pharmaceutical companies’ campaign contributions and the number of lobbyists the industry has.

“I always wanted to go to a Bernie rally, and now I feel like I’ve been there,” Paul joked after Sanders finished talking. He went on to offer his support for the Vermont senator’s amendment — a rare bipartisan alliance between senators who are on opposite ends of the political spectrum.

“This is a policy that sort of unites many on both sides of the aisle, the outrage over the high prices of medications,” added Paul. He said he didn’t support drug-price controls in the U.S. but did support a worldwide competitive free market for drugs, which he believes would lower prices.

Even before Sanders offered his amendment, the user fee bill before the committee included a limited drug-importation provision, Sec. 906. It would require the FDA to develop regulations for importing certain prescription drugs from Canada. But how this provision differs from a Trump-era regulation is unclear, said Rachel Sachs, a professor of law at Washington University in St. Louis and an expert on drug pricing.

“FDA has already made importation regulations that were finalized at the end of the Trump administration,” said Sachs. “We haven’t seen anyone try to get an approval” under that directive. She added that whether Sec. 906 is doing anything to improve the existing regulation is unclear.

Sanders’s proposed amendment would have gone further, Sachs explained.

It would have included insulin among the products that could be obtained from other countries. It also would have compelled pharmaceutical companies to comply with the regulation. It has been a concern in drug-pricing circles that even if importation were allowed, there would be resistance to it in other countries, because of how the practice could affect their domestic supply.

A robust discussion between Republican and Democratic senators ensued. Among the most notable moments: Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) asked whether importing drugs from countries with price controls would translate into a form of price control in the U.S. Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) said his father breaks the law by getting his glaucoma medication from Canada.

The committee’s chair, Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), held the line against Sanders’s amendment. Although she agreed with some of its policies, she said, she wanted to stick to the importation framework already in the bill, rather than making changes that could jeopardize its passage. “Many of us want to do more,” she said, but the bill in its current form “is a huge step forward, and it has the Republican support we need to pass legislation.”

“To my knowledge, actually, this is the first time ever that a user fee reauthorization bill has included policy expanding importation of prescription drugs,” Murray said. “I believe it will set us up well to make further progress in the future.”

Sen. Richard Burr (R-N.C.), the committee’s ranking member, was adamant in his opposition to Sanders’s amendment, saying that it spelled doom for the legislation’s overall prospects. “Want to kill this bill? Do importation,” said Burr.

Sanders, though, staying true to his reputation, didn’t quiet down or give up the fight. Instead, he argued for an immediate vote. “This is a real debate. There were differences of opinions. It’s called democracy,” he said. “I would urge those who support what Sen. Paul and I are trying to do here to vote for it.”

In the end, though, committee members didn’t, opting to table the amendment, meaning it was set aside and not included in the legislation.

Later in the afternoon, the Senate panel reconvened after senators attended their weekly party policy lunches and passed the user fee bill out of the committee 13-9. The next step is consideration by the full Senate. A similar bill has already cleared the House.

Victoria Knight is a Kaiser Health News reporter

The beauty of the useful

“Rope #1” (oil on panel), by Renee Levin, in her joint show with Jennifer Day, “Knotty Girls,’’ at Atelier Newport (R.I.) through July 22.

Ms. Levin, based on the New Jersey coast, is best known for her depiction of coastal objects. She spends a lot of time looking closely at objects on beaches.

Don Pesci: In Arles: ‘We will take you’ to our ‘Gold Coast’

Aerial view of Arles. Note the Roman arena.

— Photo by Chensiyuan

VERNON, Conn.

Whenever French President Emmanuel Jean-Michel Frédéric Macron comes to mind, more often than I would wish, my remembrance floats back to a conversation we had with François, a boat owner in Arles more French than the Eiffel Tower and more emblematic of France than Macron.

François’s boat was parked on the Rhone just below our larger boat. My wife Andrée and I were leaning over the rail, about to descend on Arles, when he called up to us in communicable English.

“Where are you from? You are American.”

“Connecticut. This is my wife, Andrée.”

“Ah, French!”

“Her father was from Trois-Rivières, Quebec. She has Indian blood in her. The French and the Indians were on amicable terms, you may recall.”

“Yes.”

He would have said “yes” in any case, because he was in the process of selling his boat.

“Americans are rich, eh?”

“Not us,” my wife responded in French. “We’ve escaped that torture.”

François laughed, a hearty boatman’s laugh, no guile in it at all.

“You should come down here. I’d like to sell my boat to you.”

We declined the offer, but joined him on the dock where his boat was berthed. He brought us some wine and cheese from his boat.

“In Connecticut,” Andrée said, once again in French, “you are right to suspect that all the roads are paved with gold, especially in Fairfield County, where I was born and raised. This is the ‘Gold Coast’ of Connecticut, but we have no gold in our pockets to buy your beautiful boat.”

The boatman’s eyes glowed. Here was a woman who understood him.

“I will show you Arles.”

And he did.

When we left him, Andrée said to François, “You have been so kind to us. If ever you come to Connecticut, you must find us.” She gave him our address. “And when you come, we will take you to Fairfield {County}, where there are many rich people and many yachts. The people there would be interested in buying your beautiful boat.”

The three of us knew that we would never see each other again. Some kindnesses must remain unpaid. He lifted her slim fingers to his lips and we said our farewell to Arles.

Later that night, bunking in our own boat, traveling south on the Rhone through Provence to Nice, Andrée said, “I can still smell the wine of the region on my hand.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Waveny Mansion, in New Canaan, in the “Gold Coast’’ of Fairfield County, Conn.

— Photo by Karl Thomas Moore

The status of youth engagement in American democracy

At the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate at the UMass Boston campus, on Columbia Point: Inside the replica of the U.S. Senate chamber.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

In the following Q&A, NEJHE Executive Editor John O. Harney asks Mary K. Grant, president of the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate, in Boston, about the institute’s work connecting postsecondary education to citizenship and upcoming elections. Edward M. Kennedy (1932-2009) was U.S. senator from Massachusetts in 1962-2009. He became known as a “liberal lion” of that body.

Harney: What did the 2016 and 2018 elections tell us about the state of youth engagement in American democracy?

Grant: We are seeing a resurgence of interest in civic engagement, activism and public service among young people. From 2014 to 2018, voter turnout among 18- to 29-year-olds increased by 79%, the largest increase among any group of voters.

The 2016 election was certainly a catalyst for galvanizing renewed interest. Since 2016, we have seen increases in people being more engaged in organizing platforms, messages and movements to motivate their peers and adults. The midterm elections brought a set of candidates who were the most diverse in our history, entering politics with urgency and not “waiting their turns” to run for office. One of the most encouraging findings was that those who felt most frustrated were more likely to vote.

While young-voter turnout in the 2018 election was historically high, it was still just 31% of those eligible to vote. Democracy depends on the voice of the people. And a functioning democracy depends on participation, particularly in polarized times. Senator Kennedy said “political differences may make us opponents, but should never make us enemies.” He envisioned the Edward M. Kennedy Institute as a venue for people from all backgrounds to engage in civil dialogue and find solutions with common ground.

As a nonpartisan, civic education organization, the institute’s goal is to educate and engage people in the complex issues facing our communities, nation and world. Since we opened four years ago, we have had more than 80,000 students come through our doors for the opportunity to not only learn how the U.S. government works, but also to understand what civic engagement looks like. All of us at the Kennedy Institute see how important it is to give young people a laboratory where they can truly practice making their voices heard and experience democracy; our lab just happens to be a full-scale replica of the U.S. Senate Chamber.

Harney: How else besides voting do you measure young people’s civic citizenship? Are there other appropriate measures of activism or political engagement?

Grant: Voter turnout is one measure, but civic engagement is needed every day. Defined broadly, activism and civic citizenship are difficult to measure. We engage in our local, state and national communities in so many ways.

Our team at the institute values reports like “Guardian of Democracy: The Civic Mission of Schools” that discuss how the challenge in the U.S. is not only a lack of civic knowledge, but also a lack of civic skills and dispositions. Civic skills include learning to deliberate, debate and find common ground in a framework of respectful discourse, and thinking critically and crafting persuasive arguments and shared solutions to challenging issues. Civic dispositions include modeling and experiencing fairness, considering the rights of others, the willingness to serve in public office, and the tendency to vote in local, state and national elections. To address the critical issues and make real social change, we need a better fundamental understanding of how our government works. And we need better skills for healthy, respectful debate.

Harney: What are the key issues for young voters?

Grant: The post-Millennial generation is the most racially and ethnically diverse generation in our history. Only 52% identify as non-Hispanic whites. As they envision their future livelihoods in an increasingly automated workplace, they are concerned about climate change and how related food security may affect the sustainability of daily life and they are concerned about income inequality, student debt, gun violence, racial disparities, and being engaged and involved in their communities.

The institute’s polling data indicated that interests for 18-34-year-olds were reflective of society as a whole, but gun rights and gun control, education and the economy would be among the most important as they are deciding on congressional candidates in the next election.

Young people are focused on the complex global issues that concern us all but with added urgency. A Harvard Institute of Politics Youth Poll this spring found that 18-29-year-old voters do not believe that the baby boomer generation—especially elected officials—“care about people like them.” And, they expressed concern over the direction of the country.

Harney: Are there any relevant correlations between measures of citizenship and enrollment in specific courses or majors?

Grant: In a democracy, we need all majors. And more importantly, we need students and graduates to know how to work together. In a global economy, people in the sciences, business and engineering work right next to people in the fields of social sciences. I had the privilege of leading two of the finest public liberal arts college and universities in the country. I am a firm believer that regardless of disciplinary area, problem-solving requires us to ask questions, to be curious and open-minded, to think critically and creatively, incorporate a variety of viewpoints and work in partnership with others. We need to understand how you take an idea, move it along and make it into something that can improve the common good.

Harney: Are college students and faculty as “liberal” as “conservative” commentators make them out to be?

Grant: From my own work in higher education, I can say that there is diversity of perspectives and viewpoints on college campuses, which is encouraging and exciting. Liberals and conservatives are not unique in the ability to hold on quite strongly to their own viewpoints. Anyone who has ever witnessed a group of social and natural scientists discuss research methodologies can attest to that. We all need to learn how to listen to ideas other than our own.

Harney: What are ways to encourage “Blue-State” students to have an effect on “Red-State” politics and vice versa?

Grant: Part of the country’s challenge in civil discourse is that we stop listening or we are listening for soundbites to which we overreact. One of the most important skills that we can develop is the ability to listen actively. It’s truly remarkable what can happen when students have an opportunity to get to know and work and learn with their peers across the country and around the world.

What we’re finding in our programs is that people are hungering for conversation, even on difficult matters. It’s similar to the concept of creating spaces on college campuses where you can intentionally connect with people. This coming fall, we’re using an award that we earned from the Annenberg Public Policy Center, at the University of Pennsylvania, to pilot a program called “Civil Conversations.” The program is designed to help eighth through 12th grade teachers develop the skills necessary to lead productive classroom discussions on difficult public policy issues. We’re starting in Massachusetts and plan to expand to all the blue, red and purple states.

And for those coming to the institute, we convene diverse perspectives through daily educational and visitor programs where people can talk with and listen to others who might be troubled or curious about the same things you are. Our public conversation series and forums bring together government leaders with disparate ideologies and from different political parties who are collaborating on a common cause; we host special programs that offer insight into specific issues and challenges facing communities and civic leaders, and what change-makers are doing about it.

Harney: What role does social media play in shaping engagement and votes?

Grant: Social media has fundamentally changed not only how we get our information, but how we interact with each other. According to a Harvard Institute of Politics Youth Poll, more than 4-in-5 young Americans check their phone at least once per day for news related to politics and current events.

As social media reaches more future and eligible voters, and when civic education is lacking, those who depend on social media platforms are at risk of consuming inaccurate information. This underscores not only the need for robust civic education programs, but also those in media literacy.

Harney: How can colleges and universities work together to bolster democracy?

Grant: Anyone who spends time around young people or on a college campus feels their energy and can’t help but come away with a renewed sense of hope. Colleges can continue to work together and advocate for unfettered access to higher education for students in all areas of the country. More specifically, they can engage with organizations like Campus Compact, a national coalition of more than a thousand colleges and universities committed to building democracy through civic education and community development.

Harney: How will New England’s increased political representation of women and people of color affect real policy?

Grant: The increasingly diverse representation helps to broaden and deepen the range of perspectives, ideas and viewpoints that influence public policy. There is also a renewed energy that is generated and it encourages next generation leaders to get involved, run for office, work on campaigns and make a difference in their communities. The institute has held several Women in Leadership programming events that highlight the lack of gender equity and racial diversity in public office and provide opportunities for women to network and learn more about the challenges and the opportunities.

Harney: Do young voters show any particular interest in where candidates stand on “higher education issues” such as academic freedom?

Grant: Students may not be focused on “higher education issues,” per se, but they do have a lot to say about accessibility and affordability. This generation is saddled with an enormous amount of student loan debt. That is certainly one of their greatest concerns, particularly when it comes to the 2020 presidential race.

Academic freedom is important in making colleges and universities welcoming to the exchange of differing ideas, which is a bedrock of democracy. As a former university chancellor, I believe that it is essential to create an environment where we welcome a diversity of opinion. We need to model the ability to listen to and consider viewpoints that may be very different from our own. We need to show students that we can sit down with people who think differently, find common ground, and even respectfully disagree. That’s a key part of what the Edward M. Kennedy Institute is all about.

‘Made fugitive with light’

“New Day”(oil on canvas), by Provincetown-based Cynthia Packard, in her show at Berta Walker Gallery, Provincetown.

The gallery says:

“A Cynthia Packard painting may start from a live model, flowers from her garden or a boat lulled by the waves. An overall textured canvas may at first sight appear purely abstract, only to reveal with further viewing, the movement of seagulls returning at dusk, or a figure emerging from the canvas. Light flows and brings alive the atmosphere around them. The works are bold, yet innocent, edgy, and deep. ‘The figures in her paintings routinely seem caught in the act of moving from one dimension to another, the body made fugitive with light,’ wrote poet Melanie Braverman. Art writer Deborah Carr writes that Packard’s paintings ‘explore paradox and contrast; consider moody interiors and verdant spaces. She juxtaposes graceful curves and sharp edges, dark contours and amorphous boundaries. The viewer of Cynthia Packard’s [painted] world realizes that remaining aloof from her powerful images is not an option.”’

Llewellyn King: Cheer up! We’re in a new age of creativity

Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922) at the unveiling, in 1916, of a plaque commemorating his invention of the telephone at 5 Exeter Place, Boston. The Greater Boston area has long been one of America’s centers of technological invention.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

You could be excused for believing that everything is going to hell. We are living through a tumultuous time, and the next two years are going to be especially difficult with severe disruption to supply chains, runaway inflation and, worst of all, food shortages in much of the world.

But it also may be a time when human creativity has never been more liberated, when fewer impediments to innovative ideas and products are coming to the surface.

John Sibley Butler, professor of management and sociology at the University of Texas at Austin’s McCombs School of Business, said on PBS’s White House Chronicle that there was a start-up surge during the pandemic, from high-tech to homemaking.

Particularly, it is a time when capital is more available to the entrepreneur than ever. Morgan O’Brien, executive chairman of Anterix and co-creator of Nextel Communications, said on the same PBS episode, “A lot of times venture capitalists are portrayed as a rapacious, unforgiving, and out-to-make-the-best-buck bunch. Our experience was so radically different. Nextel, as a company, would have been impossible without the belief, the resiliency and the support of the private equity invested in it. And the same again for Anterix.”

No longer is the sole source of capital a bank with its rigidities. No longer does the loan-seeking entrepreneur have to hear from a banker that they have no collateral. Raising capital has become a public activity, so much so that it has spurred a hugely successful network show, “Shark Tank.” Direct investment also can be found on crowd-funding platforms like Kickstarter.

Bringing a new product to market is easier than it has ever been. At one time, an inventor of a consumer product had to make a sample and then suffer abuse by a buyer in a department store chain and be told about the shortage of shelf space and the small chance of success; and to face a haggle over the pricing — if, in the remote chance, the product was approved.

Now, if you have an idea for a nifty new product, you can possibly use a 3D printer to make it at home and sell it on Etsy before you decide to raise capital and go into business full time.

Likewise, a high-tech inventor doesn’t have to beg a big company to listen and probably get an out-of-hand rejection. Instead, science-based invention is in demand, sought and cultivated. The great fortunes of recent years have nearly all been in science-based businesses.

Great fortunes have been made by venture capitalists and they are spreading out. No longer are they blinkered to examining only the possibilities of computers and the electromagnetic universe. Venture capitalists are now trolling the world for new ideas.

This creativity, this new age of discovery, is already transforming the way we live, from safer cars to a surge in new medical discoveries. Cancer, though not defeated, is being beaten back, and electricity production is getting cleaner.

The speed with which the vaccines for COVID-19 were researched, tested and produced is an inspiration for what can be done when will and need are aligned.

A new transportation future is at hand, according to Dwight Smith, a relentless Jamaican-American inventor who heads Paragon VTOL Aerospace. The Brownsville, Texas-based company is collaborating with Rolls Royce and others on vertical takeoff and landing aircraft for cargo and passengers.

The immediate bleakness in the global outlook can give way to an age redolent with possibilities so long as the talented of the United States and the world continue to produce and know that their ideas and products will find acceptance.

For example, more movies are coming to screens across the world than ever before. Netflix, Amazon, even Hallmark are offering new opportunities to writers, actors and producers. Opportunities that weren’t there a decade ago.

The trick is to keep inventing, developing and dreaming as we contend with the horrors of Ukraine, the shortages today of baby food and bulk electrical equipment, and who knows what shortages tomorrow.

And, oh, the prices! They will abate as we invent alternatives and efficiencies and we adjust our consumption.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Unreasonable nature

At the entrance to the Franklin Park Zoo, in Boston. For decades it was a terrible place for animals but has been much improved in the last quarter century.

“The world, unfortunately, rarely matches our hopes and consistently refuses to behave in a reasonable manner. The psalmist did not distinguish himself as an acute observer when he wrote: ‘I have been young, and now am old; yet have I not seen the righteous forsaken, nor his seed begging bread.’ The tyranny of what seems reasonable often impedes science. Who before Einstein would have believed that the mass and aging of an object could be affected by its velocity near the speed of light?’’

Stephen Jay Gould (1941-2002), an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, historian of science and Harvard professor, in The Panda’s Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History.

Giant Panda.

Looking at the Hub

“The Zakim {Bridge, across the Charles River}, a grand crossing” (photo), by Newton-based photographer and printer Vicki McKenna, in the group show organized by Fountain Street Gallery (Boston) entitled“Regarding Boston,’’ at Boston City Hall through June 26.

The gallery says:

“‘Regarding Boston’ features seven Fountain Street Gallery artists and multiple meanings of the word ‘regarding’ – to look at, to be about, to hold in high esteem. Curated by Melissa Shaak, the exhibition highlights Bostonians and Boston cityscapes, locations of note, and iconic sculptural details. The work assembled here portrays a vibrant and multi-faceted view of this beloved city.”

Sam Pizzigati: Keeping workers poor is bad for business

1917 caricature

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

CEOs at America’s biggest low-wage employers now take home, on average, 670 times what their typical workers make.

But we don’t just get unfairness when a boss can grab more in a year than a worker could make in over six centuries. We get bungling and inefficient businesses.

Management science has been clear on this point for generations, ever since the days of the late Peter Drucker.

Management theorists credit Drucker, a refugee from Nazism in the 1930s, for laying down “the foundations of management as a scientific discipline.” Drucker’s classic 1946 study of General Motors established him as the nation’s foremost authority on corporate effectiveness.

That effectiveness, Drucker believed, had to rest on fairness.

Corporations that compensate their CEOs at rates far outpacing average worker pay create cultures where organizational excellence can never take root. These corporations create ever bigger bureaucracies, with endless layers of management that serve only to prop up huge paychecks at the top.

Drucker argued that no executive should make more than 25 times what their workers earn. And, in the two decades after World War II, America’s leading corporate chiefs by and large accepted Drucker’s perspective.

Their companies shared the wealth when they bargained with the strong unions of the postwar years. In fact, notes the Economic Policy Institute, major U.S. corporate CEOs in 1965 were only realizing 21 times the pay their workers were pocketing.

Drucker died in 2005 at 95. He lived long enough to see Corporate America make a mockery of his 25-to-1 standard. But research since his death has consistently reaffirmed his take on the negative impact of wide CEO-worker pay differentials.

The just-released 28th annual edition of the Institute for Policy Studies’ Executive Excess report explores these wide differentials in eye-opening detail. The report zeroes in on the 300 major U.S. corporations that pay their median workers the least.

At these 300 firms, average CEO pay last year jumped to $10.6 million, some 670 times their $24,000 median worker pay.

At over 100 of these firms, worker pay didn’t even keep with inflation. And at most of those companies, executives wasted millions buying back their own stock instead of giving workers a raise.

Just as Drucker predicted, this unfairness has led directly to performance issues. Many of our nation’s most unequal companies, from Amazon to federal call-center contractor Maximus, have seen repeated walkouts and protests from justifiably aggrieved workers.

Lawmakers in Congress, the Institute for Policy Studies points out, could be taking concrete steps to rein in extreme pay disparities. They could, for instance, raise taxes on corporations with outrageously wide pay gaps.

But with this Congress unlikely to act, the new Institute for Policy Studies report also highlights a promising move the Biden administration could take on its own. The administration could start using executive action “to give corporations with narrow pay ratios preferential treatment in government contracting.”

That would amount to a major step forward, since 40 percent of our largest low-wage employers hold federal contracts. If the Biden administration denied lucrative government contracts to companies with pay gaps over 100 to 1, those low-wage firms would have a powerful incentive to pay workers more fairly.

Various federal programs already offer a leg up in contracting to targeted groups, typically small businesses owned by women, disabled veterans, and minorities.

“Using public procurement to address extreme disparities within large corporations,” the IPS report adds, “would be a step towards the same general objective.”

And a step in that direction, as Peter Drucker told Wall Street Journal readers back in 1977, would honor the great achievement of American business in the middle of the 20th Century: “the steady narrowing of the income gap between the ‘big boss’ and the ‘working man.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His latest books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Toss the cigarette and tee off

The Country Club in 1913.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The men’s U.S. Open golf tournament will be held June 16-June 19 at The Country Club, in Brookline, Mass. -- the first golf club in America to be called a “country club’’ (and for a long time known for its bigotry against some ethnic and religious groups and the dominance of Boston Brahmins).

The club was founded in 1882 but the golf course was not built until 1893.

I well remember being taken there by my father for the U.S. Open on June 20-23,1963, won by Julius Boros, who beat Jacky Cupit and Arnold Palmer in an 18-hole playoff. (No, we were not members!) The drama was delightful but it sure was hot. Watching Palmer, who was funny and charming, was great fun. (I had dinner with him and a couple of other folks at the opening of Walt Disney World in 1971.) I remember Palmer teeing off after throwing his cigarette on the ground. A more relaxed time.

Although golf courses can be environmental disasters – most are laden with chemical fertilizers and pesticides -- they can be very beautiful, which for me was more of a lure than the sport of chasing a tiny and very hard ball around 18 holes. I sometimes wish I had taken some more lessons from my father, with whom I played a few times. But I was off at school and then working in cities most of the time, and it’s a very expensive sport.

My father was a fine player, and won some tournaments, the last on the Massachusetts North Shore shortly before he dropped dead of a heart attack. After his memorial service, one of his friends said with a sigh: “He had a sweet swing.’’

The world goes its own way

Thetford, Vt., in 1912.

“Most people believe ….that any problem in the world can be solved if you know enough; Vermonters know better.’’

— John Gardner (1933-1982) in his novel October Light, set in rural Vermont.

Mid-century motifs

Susan Morrison-Dyke: “Blue Tent” (oil collage on museum board), by Boston-based Susan Morrison-Dyke, in her show “Modern Artifacts,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through June 26.

The gallery says her paintings are “inspired by mid-century modern design, inflected with Americana such as game boards and amusement parks’’.

At Riverside Park (1912-1995) Agawam, Mass., in the ‘40’s. It’s now part of Six Flags New England.

Video: Girding for big impacts from global warming in and along the Gulf of Maine

Lobster boat in Portland Harbor marina. The Maine lobster industry is threatened by the warming of the Gulf of Maine.

— Photo by Bd2media

Hit this for video about the Maine Coast facing big changes because of climate change. And hit this link about the expansion of aquaculture in Maine.

“The Maine Coast’’ (1896), by Winslow Homer.

Boston won’t pause for an audit

Part of Boston skyline from Cambridge.

“Yet Boston has never lost her universal supremacy for being independent in character, original in enterprise, unwilling to follow whenever she is reasonably equipped to lead. If she has surrendered any of her intellectual heritage, she is still too occupied in serving the humanities and human beings to pause for an audit.”

—David McCord, poet and education fundraiser (1897-1997)

The main Boston Public Library building, on Copley Square. Designed by Charles McKim, it was opened in 1895.

— Photo by Daniel Schwen

Reading Room in 1871 at the library’s first building, on Boylston Street, its location between 1858 and 1895.

David Warsh: Putin, Czar Peter and RealLifeLore

Portrait of Peter the Great, possibly by J.M. Nattier, in the Hermitage Museum, in St. Petersburg, named, of course, after that czar.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is becoming clear to dispassionate observers that, after surprising successes in its defense of Kyiv, Ukraine is losing hope that its troops can reverse gains that Russia has made in the east of the nation. A three-correspondent team yesterday put it this way in The Washington Post:

“[T]he overall trajectory of the war has unmistakably shifted away from one of unexpectedly dismal Russian failures and tilted in favor of Russia as the demonstrably stronger force.’’

In a speech June 9 to Russian entrepreneurs in St, Petersburg, marking the 350th anniversary of the birth of Czar Peter the Great, Russian President Vladimir Putin compared his invasion of Ukraine to Peter’s Great Northern War. That twenty-one-year-long series of campaigns, little remembered outside the Baltic nations, Russia, and Ukraine, began when Peter recruited Denmark and Norway as allies to test the newly crowned fifteen-year-old King of Sweden, Charles XII (sometimes called Karl XII).

Charles’s army defeated Russian forces three times its size at Narva, in 1700, and for a time Peter retreated, and began construction of St. Petersburg in 1703. But in 1709, as the over-confident Swedish king marched his army towards Moscow, via Ukraine, Peter’s forces crushed the Swedes in the battle of Poltava, effectively ending the short-lived Swedish Empire, and, as Peter the Great declared, laying the final stone in the foundations of St Petersburg and the Russian Empire. In the decade to come, Peter took possession of much of Finland and the northeastern shores of the Baltic.

“What was [Peter] doing?” Putin asked his audience Thursday, according to the Associated Press. “Taking back and reinforcing. That’s what he did. And it looks like it fell on us to take back and reinforce as well.”

Peter’s war in the Baltic was about gaining access to Europe. Putin’s war in Ukraine is about retaining access to European energy markets. It has been clear all along that the Russian invasion was about the possession of oil and gas resources and their transport. But the details are hard to explain.

My own path to the story followed the work of Marshal Goldman, of Wellesley College and Harvard Russian Research Center, who narrated Russian history after 1972 in a series of lucid books, culminating in Petrostate: Putin, Power and the New Russia (2008). But Goldman died in 2017. That left the field to Fiona Hill and Clifford Gaddy, both of the Brookings Institution, authors of The Siberian Curse: How Communist Planners Left Russia Out in the Cold, and Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin. Hill became well-known as an adviser to President Trump at the end of his term. Last week Gideon Rachman, chief foreign-affairs commentator for the Financial Times, interviewed historian Daniel Yergin to good effect in an FT podcast (s subscription may be required) .

But it turns out that the best forty minutes you can spend on the war, that is, if you have forty minutes to spend, is Russia’s Catastrophic Oil & Gas Problem, a new episode of a strange new independently produced series called RealLifeLore. Production values are striking. So is the relative lack of spin. Only the narrator’s forceful delivery wears thin, though his pronunciation of place names seems impeccable. . .

The provenance of the program itself is somewhat unclear. The YouTube link came to me from a trusted old friend; she got it from Illinois Rep. Bill Foster, the only nuclear physicist currently serving in Congress.

CuriosityStream, which carries the RealLifeLore series, is an American media company and subscription video streaming service that offers documentary programming including films, series, and TV shows. It was launched in 2015 by the founder of the Discovery Channel, John S. Hendricks. RealLifeLores’s producer, Sam Denby, is an entrepreneur best known for creating,via Wendover Productions, several edutainment YouTube channels, including Half as Interesting; Extremities; and Jet Lag, The Game. I look forward to learning more about Denby as Wikipedia goes to work and streaming networks and newspapers tune in.

I don’t know what more to say except to recommend that you watch it. It skews slightly optimistic towards the end. The Great Northern War doesn’t come into it. That’s my department, as is the is the opportunity to occasionally marvel at the yeastiness of the enterprise economy of the West, not “free” exactly, but far less clumsily guided than the system that Vladimir Putin is trying to control.

The moral of the story: Putin’s war aims are grimly realistic. Those of NATO in support of Ukraine are not. The invasion was wrong, and probably a colossal mistake, even if Russia winds up taking possession of some or all of its neighbor. Putin’s “special military operation” in the 21st Century is the opposite of Peter’s Great Northern War in the early 18th Century. Russia will suffer for decades for his folly.

xxx

Dale W. Jorgenson, of Harvard University, died June 8 in Cambridge, Mass., of complications arising from long-lasting Corona virus infection. He was 89. An excellent Wall Street Journal obituary is here.

Awarded the John Bates Clark Medal in 1971, Jorgenson was among the founders of modern growth accounting, a major force in the rejuvenation of Harvard’s Department of Economics, and, as John Fernald put it in a recently-prepared intellectual biography, attentive, supportive, warm, and kind, beneath an unfailing veneer of formality.

A memorial service is planned for the autumn.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

At least in your memory

“About a White House” (oil on panel), by Tracy Everly, at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt.

Insurrection art

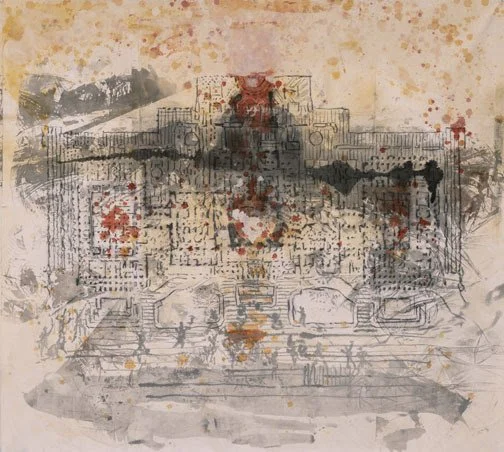

“Capitol Offense” (acylic and charcoal on blackout fabric), by Barnstable (Mass.) Village-based Jackie Reeves at the Art Complex Museum, Duxbury, Mass.

Myles Standish Monument, in Duxbury.

In Barnstable Village, on Cape Cod’s “Quiet Side’’

Clicking syllables

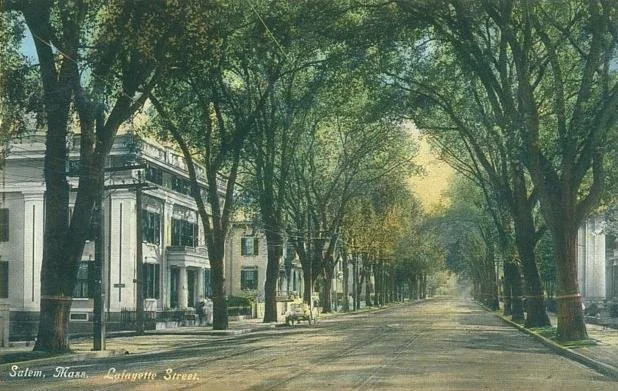

Lafayette Street in Salem, Mass. An example of the '‘high-tunneled effects’' of the American elm (Ulmus americana) once common in New England towns and cities (colorized postcard, 1910) before Dutch elm disease ravaged these beautiful trees.

— Photo by Mlane78212

“Your grandfather and I rode bikes through

an alley of trees and called their names

to each other, Latin spindling into the wind—

Acer saccharum

Betula populifolia

Pinus strobus

Syllables clicked from our mouths

like baseball cards clothes-pinned

to the bikes’ bright spokes….’’

— From “On the Day Before You Were Born,’’ by New Hampshire poet and teacher Lin Illingworth

Overcoming nature

Bullough's Pond, in Newton, Mass.

— Photo by John Phelan

“Yankee wealth is the creation of human hands, not of nature. Our soil is thin, our weather cold, and the mineral resources that lie under our mountains are negligible. Yet the people who live here are and have long been prosperous….Over and over again people in this small corner of the planet have faced disaster in the forms of economic collapse or resource dearth and overcome the odds.”

— Diana Muir in her book Reflections in Bullough’s Pond, a mill pond in Newton, Mass.

Lunar exploration

“A Different Dawn” (encaustic) by Boston-based painter Deniz Ozan George, in her show “Wax and Wane…Ebb and Flow,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, July 1-31.

She says:

"‘Wax and Wane... Ebb and Flow’ is a personal exploration of the magical and enduring presence of the moon through its many phases, its pull on the oceans' tides and its effect on the life cycles of all living things.

“These mysteries are expressed through the medium of encaustic wax painting and Japanese nihonga-inspired mineral pigment distemper painting.’’

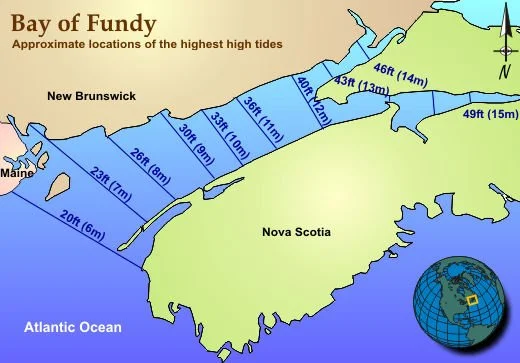

The Bay of Fundy has the highest tides in the world.

The Maria Mitchell Observatory on Nantucket was founded in 1908 and named in honor of Maria Mitchell, the first American woman astronomer. The observatory consists of two observatories - the main Maria Mitchell Observatory near downtown Nantucket and the Loines Observatory (in photo), west of downtown.