Amy Collinsworth: Amid attacks on Critical Race Theory, UMass Boston launches new institute

The UMass Boston campus from Squantum Point Park, in Quincy.The brick building in the foreground is Wheatley Hall and the white building to its right is the Campus Center.

— Photo by Fullobeans

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

Since the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and Tony McDade in 2020, among countless others, the leadership of the University of Massachusetts at Boston has publicly committed itself to becoming an antiracist and health-promoting university. The university’s stated institutional values and commitments are also intricately tied to an academic freedom that wholly defends the right to teach about race, gender and other equity issues—matters that speak directly to the lived experiences of those in our university and Boston communities.

Currently, more than 30 states have enacted bans or have bans pending related to teaching about Critical Race Theory (CRT), equity and race and gender justice. Additionally, more than 100 organizations have signed the Joint Statement on Legislative Efforts to Restrict Education about Racism and American History, a statement by the American Association of University Professors, PEN America, the American Historical Association and the Association of American Colleges & Universities, which expresses opposition to these legislative bans and emphasizes a commitment to academic freedom that includes teaching about racism in U.S. history.

While anti-CRT legislation is not currently pending in Massachusetts, there have been and remain real threats to racial justice in Boston by entities other than the state. The recent contention in Boston Public Schools about exam school admission and the defunding of Africana Studies at UMass Boston, for example, demonstrate the need for individuals, departments and organizations to commit to racial justice.

For more than 30 years, the Leadership in Education Department at UMass Boston has demonstrated its commitment to social justice in education, in part, by supporting educators for leadership roles in education, policy and community organizations. Our academic programs include Educational Administration (MEd and Certificate of Advanced Graduate Study), Higher Education (PhD and EdD) and Urban Education, Leadership and Policy Studies (PhD and EdD). As a collective, our community of faculty, students, staff and alumni is committed to research and practice that is grounded in equity, organizational change for racial justice and collaborative leadership.

Launching a new institute

As our department reflects on the changes we want to make in relation to community and racial justice, we are excited to start a new initiative that opens our department community beyond the structures of our academic programs: the Educational Leadership and Transformation Institute for Racial Justice. The institute will focus on building capacity and sustainability to transform schools, colleges and universities for racial equity.

This institute aligns with a resolution recently approved at UMass Boston to defend academic freedom to teach about race and gender justice. The institute’s programs and workshops will address issues of racial justice in education, including in teaching, learning, administration and policy. This institute makes actionable our department’s commitment to building capacity for addressing racism, whiteness and racial equity in educational institutions.

The Educational Leadership and Transformation Institute for Racial Justice is an extension of our department’s social and racial justice commitments, responding to the political and policy context in the U.S., our state and our own institution. This context includes attacks on CRT and ethnic studies at all levels and, in our own UMass Boston community, public charges of racism, defunding of our ethnic institutes and disagreement over mission and vision statement drafts on the university’s commitment to becoming an antiracist and health-promoting institution.

In the Leadership in Education Department at UMass Boston, where people of color comprise the majority of students and faculty, academic freedom is understood as central to a racial justice commitment. This is why we recently brought a resolution to our faculty governance process. The resolution, “Defending Academic Freedom to Teach About Race and Gender Justice and Critical Race Theory,’’ received a favorable vote from the UMass Boston Faculty Council. In addition to other efforts to advance racial justice within our department, throughout UMass Boston and in our professional and personal lives, we now turn to what we can do to uphold this resolution as a department through this institute.

Commitment to racial justice

With hundreds of graduates from our programs, many of whom continue to work and live in New England, our students, alumni and faculty truly lead education throughout this region. Many hold roles across public and private education, including as principals, college presidents, deans, consultants, teacher leaders, faculty members, teachers, board of trustee members, directors, elected officials and district and university administrators. As scholar-practitioners, our students explore dissertation topics that center on issues of educational equity.

The same is true of the research and scholarship that our faculty members pursue. Our members conduct research on a variety of equity-focused topics in K-12, higher education and public policy, such as African-centered education; the schooling experiences and educational and life outcomes of Black women and girls; power dynamics and conflict in the academic workplace; how students pay for college; faculty members’ work-life experiences; the design and implementation of equity reforms; critical race theory in higher education; community-engaged teaching, learning and research; developmental education; and identity-conscious leadership. We are a community committed to leadership for change.

In recent years, our department has collaborated in new ways to examine how we want to live in congruence with our social and racial justice values. Since June 2020 and the murder of George Floyd, many members of our department community have gathered as The Cypher. The Cypher is a group of students, staff and faculty who support each other in their work to advance racial justice. In our organic gatherings, we focus on healing, wholeness and taking action against racism and whiteness at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

We continue to engage in activism on our own campus, including building capacity for promoting racial justice by strengthening coalitions with other groups at UMass Boston who are also promoting racial justice. This includes several of the ethnic institutes at UMass Boston and the Undoing Racism Assembly, a university-wide group of students, staff, faculty and administrators who address different racial justice concerns on campus. We also host events for our community, like the recent “Cypher Presents” dialogue between education scholars and policymakers about current matters of educational equity impacting area educational institutions and communities.

The Cypher

We began our work in The Cypher with a document, authored by 70 people, The Cypher Report. In alignment with our administration’s commitment to antiracism and health promotion, this report calls on UMass Boston administration to take specific steps to address institutionalized inequities within our organization. In addition to supporting the restorative justice framework put forth by Africana Studies, The Cypher Report made more than 20 demands, including:

Restoring funding for the Institute for Asian American Studies (IAAS), the Institute for New England Native American Studies (INENAS), the Mauricio Gastón Institute for Latino Community Development and Public Policy, and the William Monroe Trotter Institute for the Study of Black History and Culture and rescinding the glide path toward requiring the institutes to be “self-sufficient.”

Hiring an external consultant to meet individually with each senior level administrator, dean, and department chair to assess their current understanding of the ways racism and whiteness are perpetuated at UMass Boston.

Developing a racial-equity dashboard and report card to monitor and identify inequities to improve campus racial climate and equitable educational/work experiences for the university community.

Restore the Leadership in Education Department to its full-time faculty baseline (specifically, fill the seven faculty vacancies in the department).

Our efforts to institutionalize change for racial equity as a Cypher and department—in response to the larger context highlighted above—are evident through the recent resolution we brought to the UMass Boston Faculty Council, “Defending Academic Freedom to Teach About Race and Gender Justice and Critical Race Theory’’.

Attacks on CRT have been waged through state legislation and the former federal Equity Gag Order that banned federal employees, contractors and grant recipients from addressing concepts including racism, sexism and white supremacy. In the past year, the African American Policy Forum, led by Kimberlé Crenshaw, has asked faculty councils across the U.S. to unite with those affected by this legislation. After presentations from several members of The Cypher and me, the UMass Boston Faculty Council voted to pass this resolution that rejects “any attempts by bodies external to the faculty to restrict or dictate university curriculum on any matter, including matters related to racial and social justice.” (For the full resolution, see the December 2021 Faculty Council meeting minutes.)

The resolution calls us to question what racial and gender justice mean in education, and our institute is one response to that call. Through our programs and workshops in the Educational Leadership and Transformation Institute for Racial Justice, we especially look forward to conversations among and beyond our campus community to explore the ways we engage in this work. For example, how do students feel when their cultures, histories and experiences are represented within courses taught by faculty who use a CRT lens or focus on highlighting matters of racial justice and gender justice in their classrooms? What are the implications for tenure and promotion when faculty do or do not center racial justice, gender justice and intersectionality in their scholarship? For staff members who participate in professional development related to racial and gender justice, how is participation perceived in relation to professional advancement? How often are budget decisions called into question when their focus is on initiatives of racial and gender justice? As educators and community members, we must use critical questions such as these to consider the meaning of our work beyond symbolic or performative actions if we believe equity matters.

Amy E. Collinsworth is graduate program manager and assistant to the department chair in the Leadership in Education Department at the University of Massachusetts Boston, where she is also a doctoral candidate in the Higher Education Program.

At the UMass Boston Campus Center.

Even in the winter?

Oceanic Hotel on Star Island in the Isles of Shoals.

— Photo by DavidWBrooks

“The remarkeablest Isles and mountains for Landmarks are these… Smyth’s Isles are a heape together, none neere them, against Accominiticus… a many of barren rocks, the most overgrowne with such shrubs and sharpe whins you can hardly passe them; without either grasse or wood but there or foure short shrubby old Cedars… And of all foure parts of the world that I have yet seene not inhabited, could I have but meanes to transport a Colonie, I would rather live here then any where; and if it did not maintain it selfe, were wee but once indifferently well fitted, let us starve… By that acquaintance I have of them, I may call them my children; for they have bin my wife, my hounds, my cards, my dice, and in totall my best content.”

— English explorer John Smith in 1614 about the Isles of Shoals, off New Hampshire and Maine.

—

Death in Boston

In the Head of Charles Regatta.

“Mary Winslow is dead. Out on the Charles

The shells hold water and their oarblades drag,

Littered with captivated ducks, and now

The bell-rope in King's Chapel Tower unsnarls

And bells the bestial cow

From Boston Common; she is dead….’’

— From ‘‘Mary Winslow,’’ by Robert Lowell (1917-1977)

King’s Chapel (built 1754), in Boston.

David Warsh: What Putin had hoped in assaulting Ukraine

St. Andrew Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Boston.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Two days into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the dispatch from Russia’s state-owned news service seemed to reflect Vladimir Putin’s innermost reasoning.

A new world is coming into being before our very eyes. Russia’s military operation has opened a new epoch…. Russia is recovering its unity – the tragedy of 1991, this horrendous catastrophe in our history, its unnatural caesura, has been overcome. Yes, at a great price, yes through the tragic events of what amounts to a civil war, because now for the time being brothers are shooting one another… but Ukraine as anti-Russia will no longer exist.

Instead, the Novosti account continued, the Great Russians, the Belarusians and the Little Russians (Ukrainians) would come together as a whole – a reconstituted Russian Empire. Putin had undertaken the “historic responsibility” of reunification upon himself “rather than leaving the Ukrainian question to future generations.”

The pronouncement was quickly taken down, according to Jonathan Haslam, Kennan Professor at the Institute for Advanced Study, in Princeton, N.J., describing Putin’s Premature Victory Roll in early March. It wasn’t just the over-optimism that rendered it embarrassing. It was too transparent. The goal of reunification superseded Putin’s usual complaint about the threat to Russia posed by NATO expansion.

I was broadly sympathetic to Putin after 1999, when he published his essay on Russia in the Twenty-First Century as an appendix to his First Person interview in 2000, upon taking office. I overlooked the Second Chechen War. I began paying attention after he criticized the U.S. for its invasion of Iraq in a speech in Munich, in 2007. Even after Putin’s seizure of the Crimean Peninsula, in 2014, he seemed to be within his rights, though barely. Russia had a historic claim on the peninsula on which its Black Sea naval base in Sebastopol in situated, I reasoned.

No more. Last week I re-read Putin’s article from last August, On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians. Then I read When history is weaponized for war, historian Simon Schama’s scathing criticism of it, When the Pope sought to give Putin an excuse for his invasion, in an interview with an Italian newspaper earlier this month, asserting that NATO had been “barking at Russia’s door,” it rang hollow. Nobody is talking about a Morgenthau Plan for Russia after the war in Ukraine, but nobody is talking about a Marshall Plan, either. It has options – a stronger alliance with India? But regaining its reputation in Europe looks harder than ever.

NATO’s long-term strategy of “leaning-in” seems to have worked. Putin may or may not have cancer, as a report suggested yesterday in The Times of London, but something has seriously wrong gone wrong with the man. Haslam cites Shakespeare. Putin has waged a war he cannot win. He is cementing in place the fence around him of which he complained.

Consider that his war on Ukraine has persuaded Finland and Sweden to seek to join NATO.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran. He’s the author of, among other books, Because They Could: The Harvard Russia Scandal (and NATO Enlargement) after Twenty-Five Years.

William Morgan: Less is more at RIC nursing-school building

At Rhode Island College, in the Mount Pleasant section of Providence.

— Photos by William Morgan

The home of the recently named Zvart Ononian School of Nursing at Rhode Island College is a handsome and noteworthy addition to the architectural scene in Providence. Not unlike the public-education sector that built it, and the nursing profession itself, the 12,000-square-foot facility is modest, accomplished and without pretense.

Since its beginning, in 1970, RIC’s nursing program has been in the Fogarty Life Sciences Building. In recent years it has been desperately in need of additional space. And an important need has been to establish a visual identity for the School of Nursing. Fogarty, to which the Ononian is attached, is typical of so many of the buildings at RIC: buff brick functionalism that proclaims its post-World War II public university aura.

The School of Nursing’s building went up six years ago, but received little notice until the school received $3 million this year in honor of licensed practical nurse Zvart Ononian

Rhode Island College moved out from downtown Providence to 180 acres of rolling Mount Pleasant landscape in 1958, but the countryside remained about the only thing that distinguished the campus. Its scattering of two-story, flat-roofed classroom buildings appeared like a combination of parochial high school and Midwestern agricultural college. (The style, no doubt, reflected economic reality as much as any philosophy of architects Howe, Prout & Ekman.) RIC’s architectural image started to look up with the construction of the John Nazarian Center for the Performing Arts, in 2000. The theater, designed by William Warner, a prime mover in the Providence Renaissance, has been joined by the sleek, copper-sheathed Alex + Ani Hall, by the respected Boston architects Schwartz/Silver

The Art classroom building at RIC, Alex + Ani Hall.

Unlike the art building’s stylistic variation on the theme of the earlier campus structures, the School of Nursing’s single-pitched, sloping roof creates a subtler, less institutional approach. And, instead of two stories squished together, the new building offers a high and welcoming gathering space, bathed in light from full-height windows. Gathered around this spacious hall are administrative offices, meeting rooms and simulation laboratories for hands-on training.

Inside the nursing school.

JMT Architecture, designers of the nursing school addition, have 1,600 employees, with offices in Baltimore, Philadelphia and Cleveland. While no one would confuse JMT with famous starchitects, or a small studio firm, they run a highly successful commercial enterprise that delivers dependable workmanlike buildings to satisfied clients. The RIC Nursing School doesn’t knock one’s socks off with architectural pyrotechnics, but it does not look money-starved, as publicly funded school design often does.

Entrance to Ononian School of Nursing. Thoughtful use of inexpensive materials.

The curtain wall mullions could be a little more sophisticatedly detailed, and the boxy entry vestibule is a little awkward. But the laminated timber implies strength; the entire materials palette, especially the concrete plank covering, complements the wood framing. This is a gentle, sensibly proportioned building that does not try too hard. The most appealing aspect of the school of nursing is perhaps the landscaping, where river birches set amidst natural grasses contribute a pastoral Scandinavian ambience.

Entrance to Ononian School of Nursing. Thoughtful use of inexpensive materials.

Administrators and the simulation-lab coordinator who spoke with GoLocal had only positive things to say about the nursing school building. The idea that appealing architectural design would attract students did not seem to be a consideration. Rather, it is the desire to offer an affordable nursing degree that matters. Even if the relationship of good design to academic success is unarticulated, the nursing facility is a happy place to teach and learn, as well as the attractive face of the school.

And compared to the silliness of expensive and inappropriate architectural statements, such as the fatuous RISD student center or Brown’s Performing Arts fiasco, the Zvart Ononian School of Nursing at Rhode Island is a welcome grace note.

Architecture writer and historian William Morgan is the author of a number of books about campus architecture, including Collegiate Gothic (Universty 0f Missouri Press) and The Almighty Wall (MIT Press).

And then call your cardiologist

Fish balls. Fish balls and codfish cakes were once very popular elements of New England cuisine.

— Photo by Moonguaocadine -

“She boiled three good-sized potatoes for 25 minutes; then mashed them and stirred the fish into them. To this mixture she added five eggs, five generous teaspoons of butter and a little pepper, beat everything generously together. She cooked them in deep fat, picking up generous dabs of the mixture in a potbellied spoon. The resulting fish balls, eaten with her own brand of ketchup, made ambrosia seem like pretty dull stuff.’’

--Kenneth Roberts (1885-1957), famed author of historical novels and a journalist, in Trending into Maine (1938). He was born in Kennebunk, Maine, and died in Kennebunkport.

Kennebunk River in 1903

On the waterfront of Kennebunkport. The exposed mud indicates Maine’s famously wide tidal range.

— Photo by Peter Dutton

Chris Powell: Amidst the failure to lift the poor, cities need gentrification

Approaching Wooster Square Park, in New Haven. The Wooster Street archway is decorated with a cherry blossom tree, a symbol of New Haven. It’s a reminder of the pleasure and advantages of city life, notes Chris Powell.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Especially in Connecticut, elected officials claim credit for trying to solve the problems they themselves created. It happened again recently with legislation proposed in the General Assembly to require larger municipalities to create "fair rent" commissions with power to cancel or reduce residential rent increases.

Yes, along with housing prices generally, rents have been increasing dramatically since inflation exploded. By some calculations housing has never been more expensive relative to incomes. But the legislation effectively blamed landlords when the rent increases are largely the result of government's own policies.

Impairing the ability of landlords to make money would only discourage boosting the supply of rental housing.

Connecticut policy long has allowed municipal zoning regulations to stunt the housing supply. Like rent control, restrictive zoning subverts the market. If housing was easier to build, supply would grow and prices fall.

A recent state law aims to diminish the exclusivity of suburban zoning, but it is yet to have much effect even as it is prompting anger in some towns.

The housing shortage has bigger underlying problems.

First, people want to have children but don't want to ensure that housing is available nearby for their kids when they start out on their own. Of course, peace and quiet are great but many people want government to provide peace and quiet at the expense of people who don't yet have adequate housing -- to provide peace and quiet through restrictive zoning.

And second, people justifiably want good neighbors. Quite apart from racial and ethnic prejudices, which are fading, good neighbors means that people who will behave decently, pay more in taxes than they consume in government services, and not manifest the pathologies associated with the never-ending poverty and depravity of the cities.

Connecticut's zoning-reform legislation vindicates these concerns insofar as it calls itself "fair share" legislation, confirming that new residents are a burden. Once or twice even the mayors of Hartford and New Haven have been candid about wanting to disperse their poorest residents to the suburbs. Indeed, poverty is no virtue, for with the poor come crime, dependence, and neglected children who wreck schools.

Suburbs sneer at this while city mayors have to cope with it. If government's welfare, education and urban policies were not chronic failures, suburbs might be more welcoming to new residents and to the housing construction Connecticut needs so badly.

All state government has to do is stop manufacturing poverty.

But maybe with the housing legislation Connecticut has been putting too much focus on suburbs. Lately the glorious cherry blossoms in Wooster Square Park, in New Haven, have provided a spectacular reminder of the advantages and potential of city life.

After all, the main problem with cities today is not infrastructure as much as many of the people who live there. A city with "mixed-use development" has great virtues -- commerce, industry, hospitals and medical offices, various kinds of residences, markets, restaurants, churches, theaters, and parks, all within walking distance of each other, with shops and housing often in the same buildings. In such places it is possible not just to live without a car but to be glad to be free of its expense.

Thanks in large part to Yale University, downtown New Haven somewhat sustains this way of life. Downtown Hartford lost it 60 years ago with horribly misguided urban redevelopment. But under the same mayors who would like to export their poor, both cities are waking up, striving to increase middle-class housing downtown or nearby.

Sometimes this effort is scorned as "gentrification," but gentrification is exactly what the cities need. Why is Stamford booming while Bridgeport -- only 23 miles east on the same railroad, highways and coast, with a better harbor and an airport -- sinking in decrepitude and struggling to just keep the lights on downtown?

Maybe it's because, being closer to New York City, housing in Stamford long has tended to be more expensive and so being poor there wasn't as easy as it was and remains in Bridgeport.

The poor can't be deported. So why can't Connecticut ever raise them to the middle class? Why is the decades-long failure to lift them never even officially acknowledged?

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Some detritus of commercial civilization

Painting by Lincoln, R.I.-based artist Peter Campbell in his show through June 24 at Gallery 175, Pawtucket, R.I.

The Eleazar Arnold House (built in 1693), in Lincoln, R.I., is a rare surviving example of a stone-ender, a once-common building type in New England featuring a massive chimney end wall. The houses stone work reflects the origins and skills of settlers who emigrated to New England from southwest England, and it’s a National Historic Landmark.

Dune delirium

“White Kite’’ (oil on canvas), by Kitt Shaffer, M.D., in the South Coast Artists’ Spring Invitational, at Dedee Shattuck Gallery, in Westport, Mass., through May 29.

The 75 SCA member artists will present 165 works, including works in oil, acrylic, pastel, encaustic, watercolor, metal, clay, mixed media, photography, collage, and more. For more information please visit dedeeshattuckgallery.com and southcoastartists.org.

Dr. Shaffer is vice-chair for education in radiology at Boston Medical Center. She says:

“My interest in art began in junior high school, when I took painting and jewelry making, winning a trip to Chicago for a portrait I did for a local art fair. But I never considered art as a career, since I already knew I wanted to go to medical school. In college at Kansas State, I was a pre-med, but managed to take all of the art classes I could fit in, mostly drawing (especially figure drawing), painting and sculpture. After I entered residency, I signed up for a pottery class with a friend at the Cambridge Adult Ed center, and fell in love with that, although I continued to paint and for many years, had a studio at Joy Street in Somerville, as well as a painting studio in the tiny town of Monterosso, Calabria, where we would go for a month every spring. I cannot do pottery at the moment due to the need for social distancing, we are no longer able to travel to Italy, and I had to let my Somerville studio space go, but I am hoping to be able to set up a new studio in Westport, Massachusetts, where I am spending more time now. Most of the paintings I have shared are recent work done in Westport or Italy, the drawings are from my annual teaching trips to St George’s University in Grenada, and the figurative sculpture is from several years ago done at the Harvard ceramics studio.’’

Difficult rock songs from a brainy town

Tom Scholz in 2008

“All Boston songs are fairly difficult to translate to the stage. None of them are especially easy to play or sing. A lot of them, of course, have very involved arrangements with lots of different sounds and sections that are difficult to play and sing. The prospect of doing any Boston song live is always an endeavor in itself.’’

Tom Scholz (born 1947), the founder, main songwriter, primary guitarist and only remaining original member of the rock band Boston, named after Scholz’s home town.

He’s a MIT-trained engineer who designed and built his own recording studio in an apartment basement in the early 70's. Scholz began writing songs while earning his master's degree at MIT. The first Boston album was mostly recorded in his basement studio, mostly using devices he designed and invented.

When French did empire the wrong way

The theater of the French and Indian War, 1754-1763

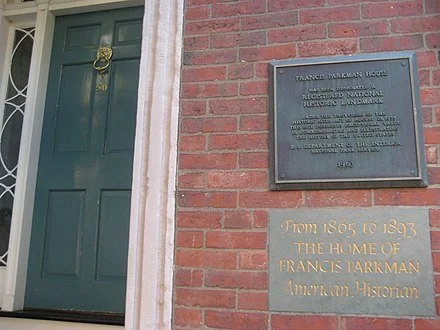

Francis Parkman House, a National Historic Landmark on Boston’s Beacon Hill

— Photo by John Stephen Dwyer

‘‘The growth of New England was a result of the aggregate efforts of a busy multitude, each in his narrow circle toiling for himself, to gather competence or wealth. The expansion of New France was the achievement of a gigantic ambition striving to grasp a continent. It was a vain attempt.’’

— Francis Parkman (1823-1893) is considered by many to be the first great American historian. Parkman was also a noted a horticulturist. His book France and England in North America is considered a masterpiece.

Holy Cross gets $2.5 million for race, gender, social-justice programs with Shakespeare thrown in

At Holy Cross; Fenwick Lawn, with Commencement Porch of Fenwick Hall in the foreground and the chapel beyond.

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) report.

“The College of the Holy Cross, in Worcester, recently received a $2.5 million gift to be used to establish an endowed chair and lecture series focused on race, gender and social justice.

“The gift comes from Eric Galloway, who graduated from Holy Cross in 1984, and named this lecture series, the Helen M. Whall Lecture Series, an endowed chair position to honor Helen M. Whall, who served as Galloway’s adviser. Whall taught at the college as an English professor from 1976 to her retirement in 2017. History Prof. Rosa Carrasquillo has been selected as the inaugural Helen M. Whall Chair in Race, Gender and Social Justice. The bi-annual lecture series in Whall’s honor will host Shakespearean scholars to come on campus and speak on issues of diversity and equity.

“‘I am honored to acknowledge Helen Whall as an inspiring professor, mentor, and friend to me and other minorities during a sometimes challenging and, ultimately, rewarding time at Holy Cross,’ said Eric Galloway.”

Confident and vulnerable in Trumpian orange

“Self” (mixed media), by Laura Harper Lake, in her show “Vivid and Vulnerable Vessels,’’ at Foundation Art Space, , N.H., June 3 through June 25.

She says: “The human form can receive varying reactions when a person views themselves with a self-assessing mind. At times we may be confident, much like the bold, vivid colors on my canvases, which are all wood. In other moments, we may feel like the thin layer of iridescent paint I use; vulnerable, exposing the natural grain beneath, and hesitant. I am a pendulum, swinging between these two radically different states of being.”

Exeter’s Squamscott Falls in 1907. The town has long hosted manufacturing enterprises, much of them originally powered by water power, but it’s best known as the home of Phillips Exeter Academy, the prep school.

Better than violence

“Family Game Night” (mixed media: game boards and pieces, cards, dice, acrylic paint), by Kristi DiSalle, in the show “Playing Games,’’ through June 19 at ArtsWorcester, whose members were invited to “submit works of art that dive into games, play and interaction.’’ Ms. DiSalle lives in the affluent rural/exurban town of Princeton, Mass.

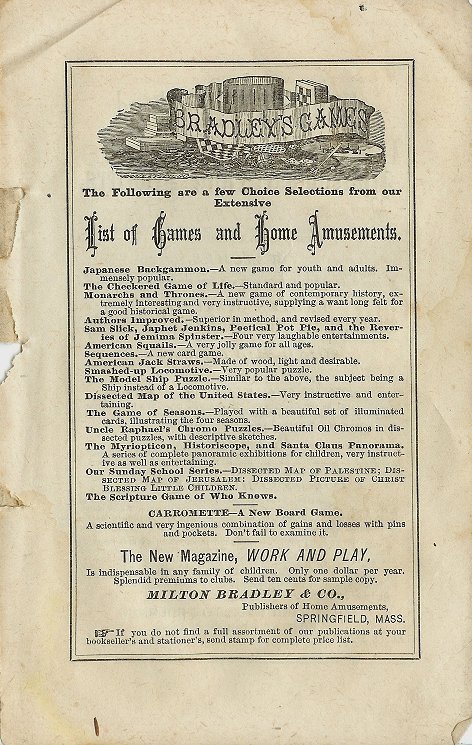

1872 ad for games created by the Milton Bradley Co., based in Springfield, Mass.

The Princeton., Mass., Public Library, built in 1883 in the heyday of stone-based Romanesque architecture made famous by the Boston-based architect Henry Hobson Richardson.

Straddling Princeton and Westminster, Mt. Wachusett, at 2,006 feet, is the highest mountain in Massachusetts east of the Connecticut and the largest ski area.

Don Pesci: 'Tax relief' and 'tax cuts' on shifting sand

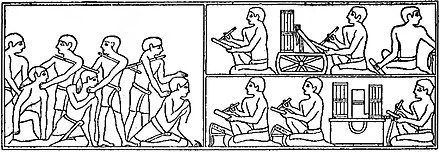

Egyptian peasants seized for non-payment of taxes several thousand years ago.

VERNON, Conn.

“The future ain’t what it used to be”

– Yogi Berra

The headline in a CTMirror story, “CT budget deal includes $600M in tax cuts, extends gas tax holiday”, includes a telling subtitle: “But more than half the tax relief is guaranteed for just one year.

There’s always a “but” in good journalism raining on someone’s parade.

The thrust of the story raises an interesting question: In what sense is “tax relief” a “tax cut”?

Many of the “tax cuts” referenced in this and other stories in Connecticut’s media are either temporary tax cuts or tax credits.

A temporary tax cut is only a “tax cut” until it elapses, after which it becomes once again a tax increase. And a “tax credit” is not, properly speaking, a tax cut. A tax, almost always permanent, moves money from a taxpayer’s budget to a state or federal treasury. A “tax cut” terminates the movement and leaves disposable assets in the account of the taxpayer.

A tax credit retains in public treasuries money moved from private to public accounts and surrenders a small part of the tax money collected to favored taxpayers.

From the point of view of the tax collector -- the state or federal government -- the beauty of a tax credit lies in the generally false appearance that those extending the credit are surrendering to preferred groups money that has been earned by state or federal government.

In moments of extreme clarity, everyone knows that a state government does not “earn” money of its own, as do private enterprises by producing and selling goods and services. States are tax collectors only, and the money they apportion belongs to tax payers who, through their own labor, earned their assets. Naturally, those surrendering money to state or federal government would like to believe political claims that the money collected would be used by government to increase the “public good.”

That is why the headline writer for CTMirror felt compelled to add to the story that clearly identifies what state Democrats and some media adepts consistently call “tax cuts” a subtitle that identifies the so called “tax cuts” as “tax relief.” A true tax cut eschews collection and leaves assets to be disposed of by a creative, enterprising and profit-seeking private marketplace. A tax credit reduces all three elements – minus a small bit of tax relief, usually temporary, apportioned for political purposes to groups favored by a reigning political party.

During election times, epistemological confusion – calling a tax credit or temporary suspension of a tax a “tax cut” – is everywhere, because give-backs and tax relief, however temporary, purchase votes, and the party in power is always interested in purchasing votes so that they may retain office and eventually raise the level of taxation to purchase vote and retain political power.

Connecticut’s temporary tax cuts and credits are built on shifting sand.

“The tax cuts,” a Hartford paper noted, “are possible because of a quickly growing state budget surplus and more than $2 billion in federal stimulus funds over 2 years that have helped fund numerous programs across the state.” The state’s budget surplus – i.e., the amount of money the state has overtaxed its citizens – is projected to reach $4 billion. And the federal stimulus funds aggravate inflation and possibly a pending recession. It takes Connecticut about 10 years to recover from a national recession.

It gets worse: The money that will finance more excessive spending is finite, and temporary, but the spending it purchases is mostly permanent and more costly than Connecticut taxpayers can afford in an era of mounting inflation, which reduces the purchasing power of the dollar, and a diminishing population.

The Yankee Institute devoted a carefully researched paper, CT’s Growing Problem: Population Trends in the Constitution State, to Connecticut’s dangerous population issues over the past few decades. The 2020 U.S. Census shows Connecticut as a negative outlier: “In a decade when the nation’s population grew by 7.4 percent, Connecticut’s population grew barely at all – less than 1 percentage point. Only 3 states ranked below Connecticut: West Virginia, Illinois and Mississippi, all of which lost population.”

If the future in Connecticut “ain’t what it used to be,” perhaps true reformers who wish to advance the public good should focus on the palpable effects ruinous policy has on the future. It is at least worth discussing whether state policy makers spend money like drunken sailors because, so long as the state can pass on to future generations the disastrous, but quite predictable consequences of hedonistic spending, politicians now serving in the General Assembly needn’t worry overmuch about their own immediate job prospects.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

Llewellyn King: For society’s sake, newspapers, whose work is looted by tech firms, deserve a reprieve

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Newspapers are on death row. The once great provincial newspapers of this country, indeed of many countries, often look like pamphlets. Others have already been executed by the market.

The cause is simple enough: Disrupting technology in the form of the Internet has lured away most of their advertising revenue. To make up the shortfall, publishers have been forced to push up the cover price to astronomical highs, driving away readers.

One city newspaper used to sell 200,000 copies, but now sells less than 30,000 copies. I just bought said paper’s Sunday edition for $5. Newspapering is my lifelong trade and I might be expected to shell out that much for a single copy, but I wouldn’t expect it of the public to pay that — especially for a product that is a sliver of what it once was.

New media are taking on some of the role of the newspapers, but it isn’t the same. Traditionally, newspapers have had the time and other resources to do the job properly; to detach reporters to dig into the murky, or to demystify the complicated; to operate foreign bureaus; and to send writers to the ends of the earth. Also, they have had the space to publish the result.

More, newspapers have had something that radio, television and the Internet outlets haven’t had: durability.

I have a stake in radio and television, yet I still marvel at how newspaper stories endure; how long-lived newspaper coverage is compared with the other forms of media.

I get inquiries about what I wrote years ago. Someone will ask, for example, “Do you remember what you wrote in 1980 about oil supply?”

Newspaper coverage lasts. Nobody has ever asked me about something I said on radio or television more than a few weeks after the broadcast.

I was taken aback when, while I was testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee decades ago, a senator asked me about an article I had written years earlier and forgotten. But he hadn’t and had a copy handy.

There is authority in the written word thay doesn’t extend to the broadcast word, and maybe not to the virtual word on the Internet in promising new forms of media like Axios.

If publishing were just another business – and it is a business — and it had reached the end of the line, like the telegram, I would say, “Out with the old and in with the new.” But when it comes to newspapers, it has yet to be proven that the new is doing the job once done by the old or if it can; if it can achieve durability and write the first page of history.

Since the first broadcasts, newspapers have been the feedstock of radio and television, whether in a small town or in a great metropolis. Television and radio have fed off the work of newspapers. Only occasionally is the flow reversed.

The Economist magazine asks whether Russians would have supported President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine if they had had a free media and could have known what was going on; or whether the spread of COVID in China would have been so complete if free media had reported on it early, in the first throes of the pandemic?

The plight of the newspapers should be especially concerning at a time when we see democracy wobbling in many countries, and there are those who would shove it off-kilter even in the United States.

There are no easy ways to subsidize newspapers without taking away their independence and turning them into captive organs. Only one springs to mind, and that is the subsidy that the British press and wire services enjoyed for decades. It was a special, reduced cable rate for transmitting news, known as Commonwealth Cable Rate. It was a subsidy but a hands-off one.

Commonwealth Cable Rate was so effective that all American publications found ways to use it and enjoy the subsidy.

United Press International created a subsidiary, British United Press, which flowed huge volumes of cable traffic through London.

Time Inc. had a system in which their cable traffic was channeled through Montreal to take advantage of the exceptionally low, special rates in the British Commonwealth.

That is the kind of subsidy that newspapers might need. Of course, best of all, would be for the mighty tech companies to pay for the news they purloin and distribute; for the aggregators to respect the copyrights of the creators of the material they flash around the globe. That alone might save the newspapers, our endangered guardians.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

'Into the moonlit woods'

“We climb into the cellar hole

of the old Bailey place

that caught fire in the middle

of the night, the seven children

who raced into the moonlit woods

in weightless clothes gowns and bedclothes’’

— From “Into the Forest,’’ by Anna Birch (1970), reflecting her experiences as a child in Hollis, N.H.

Nantucket to go topless

And after topless?

— Photo by Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1984-0828-411A / Settnik, Bernd / CC-BY-SA

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary, in GoLocal 24.com

Nantucket residents have voted 327-242 for the town to allow anyone – that means women! -- to be topless on the island town’s beaches.

The official language of the bylaw amendment called “Gender Equality on Beaches’’ (politically correct!) says:

“In order to promote equality for all persons, any person shall be allowed to be topless {even men!} on any public or private beach within the Town of Nantucket.”

Given that in the summer Nantucket hosts many rich and well-traveled people who have seen lots of topless beachgoers on, say, the Riviera or in the Hamptons, this may not be that much of a step. But the measure may lure some day trippers to engage in a little perfectly legal voyeurism.

We stay away from Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and Block Island in the summer. Too damn many people, too expensive and too much reliance on unreliable and crowded ferries. Of course, for the fat cats (mostly in finance) who increasingly dominate these luxury islands, there are their own planes.

The town on Nantucket Island when it was still called Sherburne, in 1775

‘Strange ancient memories’

Harrisville, N.H. in 1905

— From H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), writer and a Providence native who’s known for his horror and science-fiction stories.