Too wet to plant yet

“Spring Field’’ (acrylic on canvas), by Hannah Bureau, in her show “Open Air,’’ at Edgewater Gallery, Middlebury, Vt. through May 22. A native of Paris, she’s now based In Waltham, Mass.

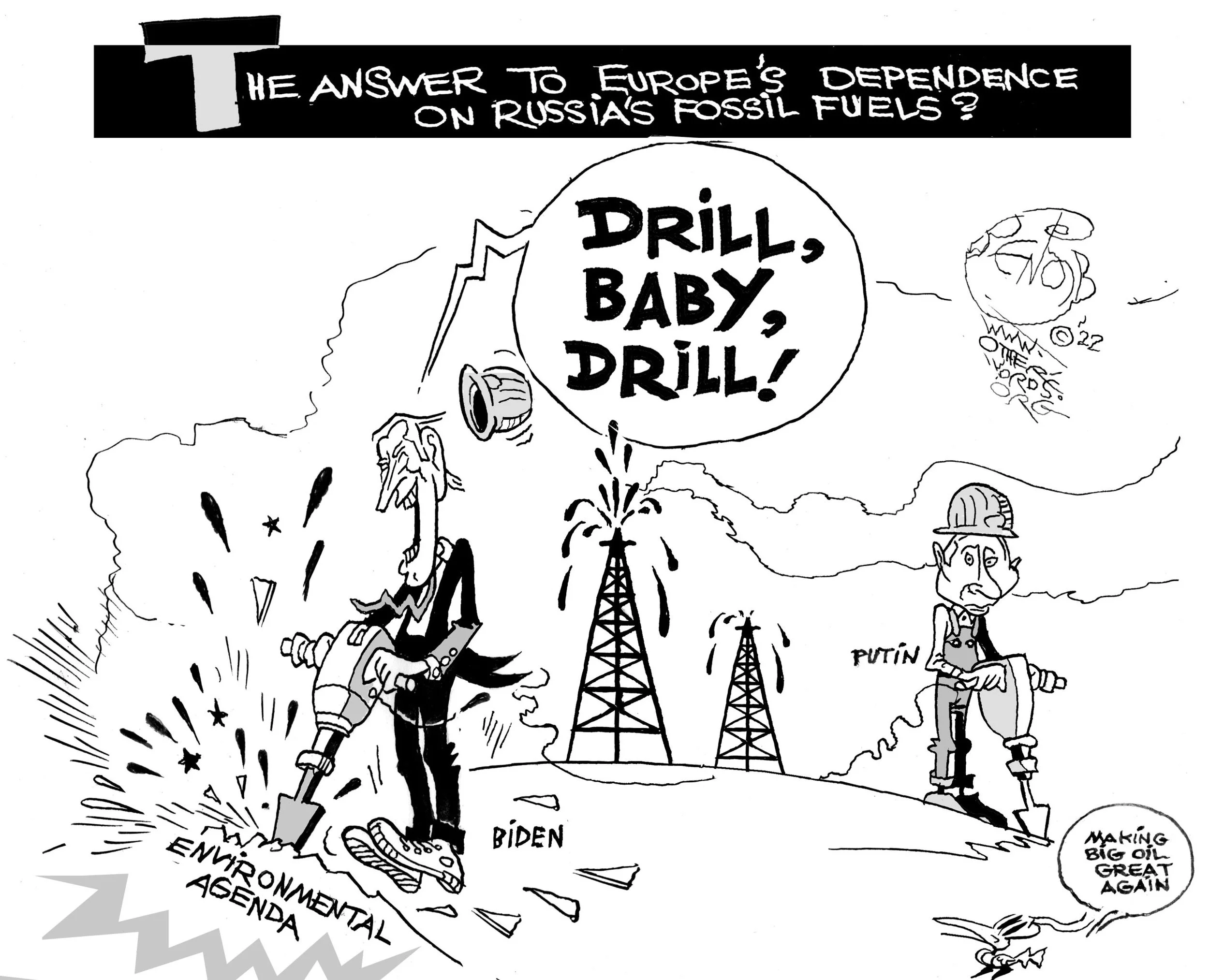

Sam Pizzigati: Time for a Tom Paine tax program

BOSTON

From OtherWords.org

The great pamphleteer of the American Revolution, Thomas Paine, had much more on his mind than independence from the British.

Paine spent his life, Jeremy Bearer-Friend and Vanessa Williamson write in a new paper, advocating for a democratic “commonwealth” that shared the wealth. He wanted to free people “from domination both political and economic.”

In particular, Paine believed that a wealth tax on grand private fortunes could prevent the emergence of an anti-democratic elite. This tax season, over two centuries later, we may finally have a president who’s taking Paine to heart.

In its new budget proposal, the Biden administration is calling for a new “Billionaire Minimum Income Tax.” The White House isn’t calling this proposal a “wealth tax,” but we should.

Under Biden’s plan, Americans worth over $100 million would be expected to pay an annual tax of at least 20 percent on their total income — including any increases in the value of their stocks, bonds, and other liquid assets.

These liquid assets make up the bulk of every billionaire fortune, but increases in their value go totally untaxed until their wealthy owners decide to sell them off. That gives “ultra-high-net-worth households,” the White House points out, the ability to have their gains “go untaxed for decades or generations.”

Let’s take the example of a CEO who pockets $20 million a year in salary. He might pay a 20 percent tax on that $20 million.

But if this executive also holds stocks worth $10 billion and those stocks gain 10 percent in value — an extra $1 billion — then the vast majority of our CEO’s real income would go completely untaxed.

Under Biden’s plan, that CEO would have to pay taxes on his CEO pay and all his stock gains. That would hike his federal tax tab from $4 million to $204 million.

America’s 700 or so billionaires, the Biden administration notes, saw “their wealth increase by $1 trillion” last year. Yet current law has billionaires paying “just 8 percent of their total realized and unrealized income in taxes.”

That’s right: Billionaires pay at a lower overall rate than average Americans.

“Under current law, when an American worker earns a dollar of wages, that dollar is taxed as they earn it,” the White House explains. “But when a billionaire earns income because their investments increase in value, that gain is too often never taxed at all.”

Firefighters and teachers, adds the White House, “can pay double” the rate billionaires pay.

The Biden tax plan is actually taking much the same approach that Tom Paine took with a wealth tax proposal he first put forward in 1792, tax historians Bearer-Friend and Williamson argue.

Under Paine’s plan, the pair calculate, today’s billionaires would pay a tax of about 3.5 percent of their personal fortunes during normal market years. That figure is remarkably close to the tax rates that appear in wealth tax proposals that Senators Elizabeth Warren (D.-Mass) and Bernie Sanders (I.-Vt.) have advanced.

Biden’s plan doesn’t take that big a bite. But it does represent a significant step toward taxing the wealth of America’s wealthiest, says Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman.

Mega-billionaires Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett, and Elon Musk, Zucman reminds us, together paid just $1.5 billion in federal income taxes over the five-year period that ended in 2018. Under the Biden proposal, this trio would pay at least 100 times more over the next decade or so.

Paine believed that extreme wealth undermines “the ability of citizens to choose their leaders,” Bearer-Friend and Vanessa Williamson argue, a condition that many will easily recognize today. Freedom, in Paine’s view, “meant both lifting the poor from penury and dependence” and eliminating the “vicious influence” of fiercely concentrated wealth.

Tom Paine had it right. And if Congress takes up Biden’s new tax plan, we can too.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His latest books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

‘Climbed into my head’

Spring rusts on its skinny branch

and last summer's lawn

is soggy and brown.

Yesterday is just a number.

All of its winters avalanche

out of sight.

What was, is gone.

Mother, last night I slept

in your Bonwit Teller nightgown.

Divided, you climbed into my head.

— From “The Division of Parts,’’ by Anne Sexton (1928-1974), Boston area Pulitzer Prize-winning poet

Sunset for the demented

Sunset at Menemsha Harbor

“Menemsha. An old Native American name freely translated as “place where demented aliens gather to applaud the setting of the sun while eating supper in the sand.’’

— Arnie Reisman, in On the Vineyard II (1990)

Picturing Pownal

“Sunday, 1937 ” (oil on canvas), by Marion Huse, in the show “Marion Huse: Picturing Pownal’’, at the Bennington (Vt.) Museum through June 22.

The museum says:

“Huse’s work spanned forty years and a variety of styles and subject matter, from Regionalism in the 1930s to a more Expressionistic style that she developed in the post-war years. A selection of her prints, depicting historic local landmarks and covered bridges, will be shown alongside her paintings.’’

Former Country Store in Pownal, Vt.

— Photo Doug Kerr

Buzzards Bay riviera

Sippican Harbor, in Marion, Mass. on the South Coast

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I read in GoLocalProv the other week that Residential Properties, the Providence-based company that has a particular affection for high-end customers, has set up an office in Westport, Mass. No wonder! The South Coast region has drawn many more summer and year-round home buyers in the past few years, drawn by the beautiful rolling countryside (with vineyards and farms), Buzzards Bay, which is remarkably warm in the summer, and the ease of getting to the area.

It’s lured a lot of people who in prior years might have gone to Cape Cod or the Hamptons.

This migration has shot real-estate prices through the roof on the South Coast (in which I’d include the coastal towns from Little Compton all the way to Marion (but excluding New Bedford). The big surprise to me is how long it took so many people to discover it.

Dartmouth High School logo

One man’s honor, another’s insult

The voters of Dartmouth, Mass., on the South Coast, have backed – 4,048 to 969 -- the retention of the almost-abstract face of a Native American brave as the logo for the town’s high school.

Some members of the locally dominant Wampanoag Tribe wanted it gone. But other members find it a dignified and respectful reminder of the original inhabitants of what became Dartmouth. The logo was designed by Wampanoag Tribe member Clyde Andrews.

Taking offense can be an unpredictable and highly individual thing.

‘Shapeshifting beauty’

“Harmony” (oil and wax on copper panel), by Brookline, Mass.-based Nora Charney Rosenbaum, in her show “The Language of Birds,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, May 1-June 1.

“When I see a colony of cormorants silhouetted on seashore rocks, their shapes can seem like cryptic hieroglyphs from some arcane mythology. Looking closer, they become recognizable as individual characters in a dialog of social interactions.

“In my painting I try to capture their rangy, shapeshifting beauty. Using oil paint and sometimes wax and sand on copper-covered panels helps me express their liveliness."

She says in her artist statement:

“For me the process of painting is the solving of problems - color, form, texture and composition. My technique is to layer oil paint in thin glazes or sometimes mixed with wax over chemically treated copper to produce an optically complex surface. Light passes through some layers and reflects off others to give an impression of atmosphere and luminescence.

“Painting is always a leap into the unknown. Trying to capture the depth, motion and sense of transparency in this ephemeral world is a challenge.’’

Boston Harborwalk

“East Boston Boat Yard” (photo), by Alan Strassman, in his show “Boston Harbor: Views From the Shoreline’,’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, May 1-June 1.

Mr. Strassman explains:

"For more than 30 years, the City of Boston, Massachusetts state agencies, private developers and waterfront residents have been working together to create the Boston Harborwalk – a pedestrian-friendly walkway running more than 40 miles from Dorchester in the south to Winthrop in the north.

“These are some scenes from the edge of the harbor."

New England's indigenous horse

A young Morgan horse

At the Morgan Horse Farm, an historic breeding facility in Weybridge, Vt. Since 1907, it has been an official breeding site for the Morgan horse, one of the first American-bred horse breeds, and Vermont's official state animal. The breeding program was established in Burlington in 1905, and moved to this site in 1907 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and is now run by the University of Vermont. The farm is in the National Register of Historic Places.

“Close-coupled, sturdy, winsome, with a well-defined head and delicate ears, the Morgan horse is New England’s indigenous breed. The line goes back to a small bay stallion owned by Justin Morgan, a Vermont schoolteacher-farmer, who acquired the remarkable colt in 1795. For 32 years this stalwart animal served honorably under saddle and in harness. All Morgans descend from him.’’

Maxine Kumin (1925-2014) , Warner, N.H.-based poet and horse farmer, in Arthur Griffin’s New England: The Four Seasons

Free lunch

“In the Clover” (watercolor), by Jeanette Fournier, a North Woodstock, N.H., painter.

Woodstock Inn Brewery, in North Woodstock

— Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

Judith Graham: Beliefs about aging affect longevity

People’s beliefs about aging have a profound impact on their health, influencing everything from their memory and sensory perceptions to how well they walk, how fully they recover from disabling illness, and how long they live.

When aging is seen as a negative experience (characterized by terms such as decrepit, incompetent, dependent and senile), individuals tend to experience more stress in later life and engage less often in healthy behaviors such as exercise. When views are positive (signaled by words such as wise, alert, accomplished, and creative), people are more likely to be active and resilient and to have a stronger will to live.

These internalized beliefs about aging are mostly unconscious, formed from early childhood on as we absorb messages about growing old from TV, movies, books, advertisements, and other forms of popular culture. They vary by individual, and they’re distinct from prejudice and discrimination against older adults in the social sphere.

More than 400 scientific studies have demonstrated the impact of individuals’ beliefs about aging. Now, the question is whether people can alter these largely unrecognized assumptions about growing older and assume more control over them.

In her new book, Breaking the Age Code: How Your Beliefs About Aging Determine How Long and Well You Live, Becca Levy of Yale University, a leading expert on this topic, argues we can. “With the right mindset and tools, we can change our age beliefs,” she asserts in the book’s introduction.

Levy, a professor of psychology and epidemiology, has demonstrated in multiple studies that exposing people to positive descriptions of aging can improve their memory, gait, balance, and will to live. All of us have an “extraordinary opportunity to rethink what it means to grow old,” she writes.

Recently, I asked Levy to describe what people can do to modify beliefs about aging. Our conversation, below, has been edited for length and clarity.

Becca Levy, a professor at Yale University, studies the way our beliefs about aging affect physical and mental health.

Q: How important are age beliefs, compared with other factors that affect aging?

In an early study, we found that people with positive age beliefs lived longer — a median of 7.5 additional years — compared with those with negative beliefs. Compared with other factors that contribute to longevity, age beliefs had a greater impact than high cholesterol, high blood pressure, obesity, and smoking.

Q: You suggest that age beliefs can be changed. How?

That’s one of the hopeful messages of my research. Even in a culture like ours, where age beliefs tend to be predominantly negative, there is a whole range of responses to aging. What we’ve shown is it’s possible to activate and strengthen positive age beliefs that people have assimilated in different types of ways.

Q: What strategies do you suggest?

The first thing we can do is promote awareness of what our own age beliefs are.

A simple way is to ask yourself, “When you think of an older person, what are the first five words or phrases that come to mind?” Noticing which beliefs are generated quickly can be an important first step in awareness.

Q: What else can people do to increase awareness?

Another powerful technique is something I call “age belief journaling.” That involves writing down any portrayal of aging that comes up over a week. It could be a conversation you overhear in a coffee shop or something on social media or on your favorite show on Netflix. If there is an absence of older people, write that down, too.

At the end of the week, tally up the number of positive and negative portrayals and the number of times that old people are absent from conversations. With the negative descriptions, take a moment and think, “Could there be a different way of portraying that person?”

Q: What comes next?

Becoming aware of how ageism and age beliefs are operating in society. Shift the blame to where it is due.

In the book, I suggest thinking about something that’s happened to an older person that’s blamed on aging — and then taking a step back and asking whether something else could be going on.

For example, when an older adult is forgetful, it’s often blamed on aging. But there are many reasons people might not remember something. They might have been stressed when they heard the information. Or they might have been distracted. Not remembering something can happen at any age.

Unfortunately, there’s a tendency to blame older people rather than looking at other potential causes for their behaviors or circumstances.

Q: You encourage people to challenge negative age beliefs in public.

Yes. In the book, I present 14 negative age beliefs and the science that dispels them. And I recommend becoming knowledgeable about that research.

For example, a common belief is that older people don’t contribute to society. But we know from research that older adults are most likely to recycle and make philanthropic gifts. Altruistic motivations become stronger with age. Older adults often work or volunteer in positions that make meaningful contributions. And they tend to engage in what’s called legacy thinking, wanting to create a better world for future generations.

In my own case, if I hear something concerning, I often need to take time to think about a good response. And that’s fine. You can go back to somebody and say, “I was thinking about what you said the other day. And I don’t know if you know this, but research shows that’s not actually the case.”

Q: Another thing you talk about is creating a portfolio of positive role models. What do you mean by that?

Focus on positive images of aging. These can be people you know, a character in a book, someone you’ve learned about in a documentary, a historical figure — they can come from many different sources.

I recommend starting out with, say, five positive images. With each one, think about qualities you admire and you might want to strengthen in yourself. One person might have a great sense of humor. Another might have a great perspective on how to solve conflicts and bring people together. Another might have a great work ethic or a great approach to social justice. There can be different strengths in different people that can inspire us.

Q: You also recommend cultivating intergenerational contacts.

We know from research that meaningful intergenerational contact can be a way to improve age beliefs. A starting point is to think about your five closest friends and what age they are. In my case, I realized that most of my friends were within a couple of years of my age. If that’s the case with you, think about ways to get to know people of other ages through a dance class, a book club, or a political group. Seeing older people in action often allows us to dispel negative age beliefs.

Judith Graham is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

The bellhop in hazmat suit will take you to your lab

The Hotel Buckminster (built in 1897), at Boston’s Kenmore Square, in about 1900; space for the future Fenway Park is at left. The shuttered hotel will reportedly be bought for $42.5 million by development company IQHQ and turned into — what else these days in Boston and Cambridge!? —biotech lab space.

The hotel was where the plot to fix the 1919 World Series was allegedly launched.

2009 photo

— Photo by John Stephen Dwyer

Cynthia Drummond: Nurture New England’s native plants

Blossoms of mountain laurel, a common shrub in southern New England

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A story in a recent issue of a national gardening magazine extolled the benefits of “naturalistic garden design,” a less constrained landscape that features native plants grouped in ecologically compatible communities.

The reader was encouraged to look for inspiration in the local ecosystem and to “suspend fussiness” to develop a wilder, more resilient garden that is in tune with the surrounding natural landscape.

Magazine articles about native plants indicate their growing acceptance as garden plants, but because they have co-evolved over thousands of years with native insect and bird species, these plants play a much more critical role.

David Gregg, director of the Rhode Island Natural History Survey, described native plants as central components in the evolution of the Rhode Island ecosystem.“They’re the environment and context in which all the other animals in our plants in our area evolved,” he said.

“So, the bees’ tongues are the right length to get the nectar from the flowers. The birds can eat the caterpillars that that eat those plants. The soil microbes are such that those plants can get nutrients from the soil instead of fertilizer.”

While gardeners have differing opinions on how “native” a plant should be, whether a garden should contain only native species, and whether those species should be native to Rhode Island, New England or beyond, more people are choosing to plant natives, even if it’s just a few to start. This higher level of awareness is evident in the recent growth of the membership of the nonprofit Rhode Island Wild Plant Society, which, in the past two years, has gone from about 400 members to more than 600.

Society vice president Sally Johnson said she is not sure why the organization has so many new members, but she said it is probably due to people spending more time at home as well as growing concerns about the climate crisis.

“A lot of us are out in our yards, outside more, and a lot of us are going for more walks because it’s COVID-safe, so we’re appreciating nature more, and that’s got to contribute to it,” she said. “The other factor, and this is my gut feeling on it, it’s got to be global warming. We see so much environmental destruction. There’s so much talk of resiliency. That contributes.”

Johnson also noted people were becoming more aware of the need to support pollinating insects and birds.

“People are going from the purely ornamental, showy plants, and understanding more the role of supporting pollinators and host plants,” she said. “The understanding of, it’s not just the pretty bees and butterflies, but it’s also the wasps and who’s going to live there over the winter and leaving your perennials up over the winter so that insects can overwinter in them.”

Michael Adamovic, author, photographer and and a botanist at Catskill Native Nursery, attributes the greater interest in native plants to the noticeable decline in insect populations.

“Natives are definitely increasing in popularity,” he said. “Probably one of the main reasons is that because in the last 20, 30 years, there’s been a large decline in insect populations. You would take a road trip, 20 or 30 years ago, and your car would be completely covered with insects. These days, you’re lucky if you get one or two splattered on it. The same thing goes for songbirds. The songbird population is really starting to decline, and people are finally starting to realize there’s something wrong with the environment.”

Adamovic said sales at the nursery took off during the pandemic and continue to be strong.

“Our sales probably at least doubled from the previous year,” he said. “We couldn’t keep up with the demand. And even last year, 2021, it was still going in the same direction and there’s no indication of it slowing down.”

Johnson, who owns a garden design business that uses native plants, said they can still be hard to source in Rhode Island, and she often has difficulty finding them for her clients.

“You can’t find native species,” she said. “… I had a client who had to put in native plants for a CRMC [Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council] permit by the end of October and she could only put in three species.”

The Rhody Native program, a federally funded initiative of the Rhode Island Natural History Survey, began in 2010, but ended in 2018. The initial objectives were to provide enhanced job training for unemployed nursery workers following the recession, and plant native species to fill the spaces where invasive plants had been removed.

“The idea was, all right, here’s another economic opportunity,” Gregg said. “Let’s gather seed and cut clippings from local sources and we’ll pay out-of-work nurserymen to grow them up for us. And then, we will use them in restoration projects and we’ll let nurseries and garden centers sell them to try to change people’s minds about natives.”

But when the federal funding ended, the idea of building a local native plant supply chain ran up against the realities of the nursery business.

“You can’t pay a professional staff on the kind of volume we were doing in Rhody Native plants, and there’s a couple of reasons,” Gregg said. “One is, the margins on propagating nursery stock are so thin, you have to do zillions of plants in order to make a business out of it. For native plants, you still have to order from far away because it won’t pay. We didn’t have the right model for making local plants pay.”

There was also an issue, Gregg added, with a tax-exempt nonprofit operating on tax-exempt land competing with commercial growers in Rhode Island.

Current garden trends favor native plants, a change Adamovic has also observed.

“They are going more toward native plants than they are non-native,” he said. “We still get a few people who don’t get it at all. They’ll come in and have this huge list of non-natives. They don’t really understand what the whole native thing is about, but every year that goes by, that’s decreasing.”

Johnson believes gardeners evolve at their own pace, and some people will adopt native plans more readily than others.

“I think you have to accept people for where they are and try to just gently move them,” she said. “We as a wild plant society are trying to move towards being purists, of only selling plants from Rhode Island and trying to get out seeds from Rhode Island, and I totally support that effort. … It’s important to realize that hey, if you don’t want to do your entire garden as native plants, at least start putting some in and start looking at them and thinking about them, and then you realize ‘Hey, the native goldenrod is kind of nice.’”

It is becoming increasingly important, Adamovic said, that people include native plants in their gardens.

“It’s really rewarding, too,” he said. “You put a native plant in your garden and you’re able to see that the caterpillar that ate it turned into a butterfly. You’re also providing a bunch of food for wildlife in general, and you’re really helping to save the environment by switching over to using natives.”

For Gregg, native plants are the foundation of Rhode Islanders’ sense of place.

“Rhode Islanders live in a place that has oak trees that drop their leaves in the winter and it’s got stone walls with moss and asters growing along them and it’s got native beach grasses,” he said. “You go to the beach, you see the little waving grasses. … If you want a place with palm trees and eight foot-high elephant grass, go somewhere else. Rhode Island is about a sense of place. It’s about our native plants.”

Native plant resources

Rhode Island Wild Plant Society native plant sales.

Xerces Society pollinator-friendly native plant lists.

Cynthia Drummond is an ecoRI News contributor.

Oh come on! There were others

Bedford(N.H.) Presbyterian Church

“We had no religion at all, but we were Jews in New Hampshire, and my sister – who is now a rabbi – said it best: We were, like, the only Jews in Bedford, New Hampshire, as well as the only Democrats, so we just kind of associated those two things together. My dad raised us to believe that paying taxes is an honor.”

— Roseanne Barr (born 1952), American comedian and actress

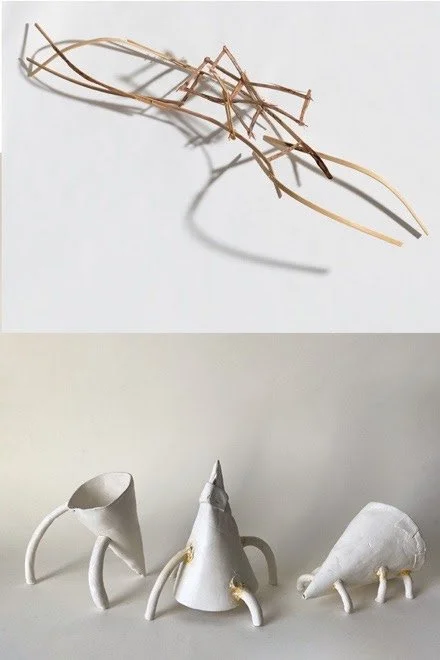

Sculpture that crawls

Both at Boston Sculptors Gallery:

Top: “Carry” (wood, waxed linen and ink), by Somerville-based Julia Shepley. The gallery says that the show “features a series of inventive open-framework wood sculptures in procession with their shadows paired with a selection of new drawings and prints.’’

Bottom: “Three Types of Equilibrium (mixed media), by Kathleen Volp, in her show “Pointed.’’

“Pointed” comprises “small groupings of geometric forms made primarily from plaster, paper pulp and clay displaying humor and intrigue in the most elemental.’’ Ms. Volp lives in Waltham, Mass., and Cavendish, Vt.

Downtown Cavendish Vt. — during rush hour?

‘Panting like spaniels’

“Climbing the stairway gray with urban midnight,

Cheerful, venial, ruminating pleasure,

Darkness takes me, an arm around my throat and

Give me your wallet.

Fearing cowardice more than other terrors,

Angry I wrestle with my unseen partner,

Caught in a ritual not of our own making

panting like spaniels….”

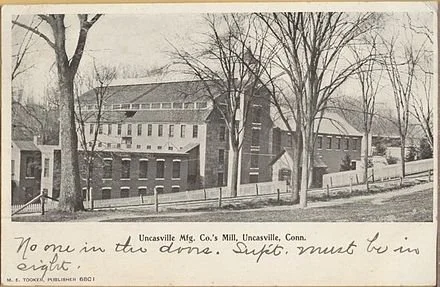

— From “Effort at Speech,’’ by William Meredith (1919-2007), U.S. poet laureate in 1978-1980. He taught at Connecticut College, in New London, and had a farm on the Thames River in nearby Uncasville, an old mill village in the town of Montville. He became a very able arborist.

The admissions building at Connecticut College, founded in 1911 as "Connecticut College for Women" in response to Wesleyan University, in nearby Middletown, closing its doors to women in 1909; it shortened its name to "Connecticut College" in 1969, when it began admitting men.

Uncasvillle Mill in 1906, in its industrial heyday

Potatoes and canoes in Maine's big country

Children gathering potatoes on a large farm in Aroostook County in1940. In those days, schools did not open until the potatoes were harvested. The country long competed with Idaho to be considered the potato capital of America.

— Photo by Jack Delano

“This is big country, larger than Connecticut and Rhode Island combined, nearly the equal of Massachusetts; its vastness is more suggestive of the West than of New England. It winters, people will tell you, are fiercer, its forests thicker, it rivers wilder than anywhere else in the East.’’

Mel Allen, on Aroostook County, Maine, in “There’s No Easy Way to Pick Potatoes,’’ in the September 1978 issue of Yankee magazine. Mainers simply call Aroostook “The County’’. Its voters tend to favor right-wing politicians.

Allagash Falls on “The County’s” Allagash River

A growing romance

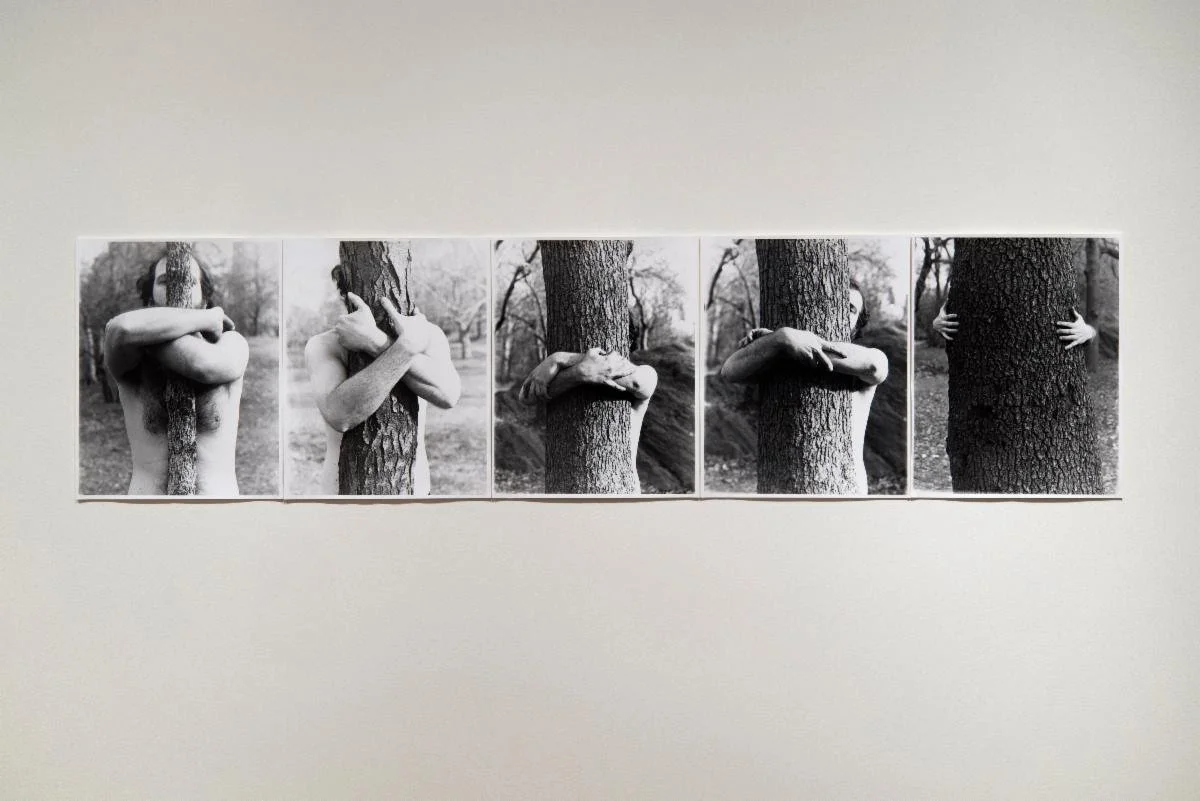

“Myself Becoming One with the Tree” (photo), by Alan Sonfist, in his show “Becoming Trees” (curated by Fritz Hortsman), at Concord Art, Concord, Mass., through May 8.

Mr. Sonfist is a New York City-based American artist best known as a trailblazer of the Land or Earth Art movement.

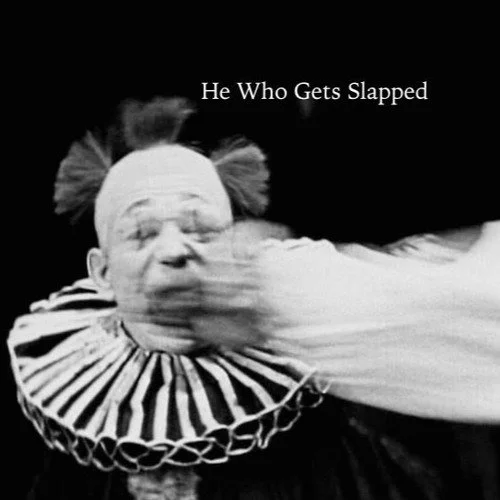

Llewellyn King: The beauty of a woman’s slap

I have never met Will Smith, but I would like to just so that I could pump that hand — the hand that connected with Chris Rock’s cheek at the Oscars; the slap that was seen around the world.

That hand connecting with that unsuspecting cheek should start us on a happy back-to-the-future journey.

I would rather the striker had been a woman. Slapping men’s faces has a long and honorable tradition in female defense of rectitude.

We need to reinstall the periodic slapping of the male face as a part of the interaction between men and women so there are fewer instances of #MeToo. Once there has been a slap, there can be no later debate about who allowed what. An open-handed blow to the over-eager male face is declarative: Cut it out now. It is the unique female form of defense without having to take up judo, kickboxing or succumbing to unwanted advances. Slapping the pushy male face is, or was, instinctive.

A crisp slap of the face puts a definite and embarrassed end to “inappropriate touching.” A face slap is so articulate, so incontrovertible, so absolute and so very effective. It doesn’t ever get confused with “consensual,” “maybe” or “perhaps.”

Had a few more faces been slapped, there would be fewer TV personalities sitting out their lives in early retirement because they said they thought there was mutual consent. Had the face of one governor been slapped, he would have restrained his unlicensed hands from roving where they shouldn’t have, and he would still have a job. No equivocation or doubt; no he-said, she-said. A slap is a notable event, never forgotten by the deliverer or the receiver.

Neither the slapper nor the slapped quickly forgets the inside of the female hand swiftly connecting with the outside of the male face. It hurts the male ego far more than it stings the offending cheek or the delivering palm.

Question: Did she slap your face? How can a man answer that without a simple “yes” or “no”? A slap can’t later be confused with foreplay. You weren’t desired is an unambiguous statement implicit in the face slap. Once thus discouraged, further advance is not allowable, or is the beginning of #MeToo territory.

What happened to face slapping? Why did it go the way of couches in women’s restrooms and nose-powdering, as in “I have to powder my nose.” Such a delightful euphemism. Somewhere in the women’s movement some useful things got lost.

The last time, as I remember, when a face slap echoed around the world was when Vivien Leigh, playing Scarlett O’Hara in the movie Gone With the Wind, brought an open palm against the astounded cheek of Clark Gable, playing Rhett Butler.

When a woman delivers the unambiguous slap to the face of an over-eager man, she has an opportunity to accompany it with a solid verbal rebuke; to append a testy codicil. How about one of these: “What kind of women do you usually go out with?” “How dare you, lover boy?” “I told you, keep your hands to yourself.” Or a withering, “What do you think you’re doing?” That should deflate the aspiring Don Juan and send the putative lover back to computer dating.

You are probably wondering how often this writer’s face has been slapped? Only once, in quite a different circumstance and for quite a different offense. It was a shock, an ego-crusher, and I have an indelible memory of it.

Despite the current imbroglio between Will Smith and Chris Rock, the face slap remains uniquely a woman’s prerogative and a man’s shame. Whack!

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.