"Vastness and fragility'

MetalScape 106 (encaustic, anodized copper aluminum, UV resin on panel), by Boston-based Charyl Weissbach

She writes:

“I explore nature’s vastness, simplicity and fragility. These elements emit aesthetic sensations of harmony, expressions of timelessness and feelings of inspiration that transcend space and time. The imagery of my work does not accurately represent nature; rather, I try to unveil an abstraction of its character to raise awareness for the preservation of our world.”

“{My} ‘MetalScape’ paintings represent a dialogue between nature’s expansiveness and its awe-inspiring simplicity. Color and composition are reduced to a minimalist stillness so that form becomes the focus. The imagery of these paintings does not accurately represent nature; rather, they unveil an abstraction of its character, capturing infinite variations of ethereal beauty. …

“Ocean acidification, a deadly threat to marine life, compromises the long-term viability of these ecosystems and impacts an estimated one million species that depend on its coral reef habitat. Half a billion people worldwide depend on coral reef ecosystems for protection, food, and income.”

“Fortunately, assisted organism evolution techniques being performed in marine laboratories here and abroad are well underway, striving to save corals from extinction. Additionally, geo-engineering technologies are helping to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide and the acidity of our oceans without the need to drastically cut carbon emissions.”

Ms. Weissbach makes her paintings in the SoWa Art & Design District (South of Washington St.) in the South End of Boston. SoWa is a community of artist studios, contemporary art galleries, boutiques, design showrooms and restaurants. Scene above is next to the SoWa open market.

Eat oysters to fight global warming

“Still-Life with Oysters,’’ by Alexander Adriaenssen

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Eating oysters is good for the environment, according to a pair of Narragansett Bay-centric experts. Scientists Robinson Fulweiler, of Boston University, and Christopher Kincaid, from the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography, shared their latest findings during a webinar last fall.

Fulweiler studies the impact that wild and aquaculture oysters have on their surrounding waters. A single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water daily. Their most important service, and the one Fulweiler studies most, is removing nitrogen from marine waters that could trigger algal blooms.

“Aquaculture, as well as restored oyster reefs, have high rates of nitrogen removal,” Fulweiler said.

Excessive nitrogen in waters such as Narragansett Bay is dangerous for aquatic habitats and marine life, as it can feed toxic blooms. These events are also linked to low levels of oxygen in the water, which can lead to fish kills like the one in Greenwich Bay in 2003 that killed tens of thousands of fish.

Oysters, including those in aquaculture operations, help out by removing nitrogen and other pollutants from stressed waters. Instead of being biologically available to feed algae growth, the chemical used in fertilizers is released into the atmosphere as nitrous oxide. Aquaculture and restored reefs have a strong impact on denitrification, according to Fulweiler.

“Oyster aquaculture and oyster reefs are behaving similarly in terms of the nitrogen removal process,” she said.

The two biggest greenhouse gases that oysters emit are nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide, and while they are powerful climate emissions, the amounts that oysters release as part of denitrification are negligible. In fact, Fulweiler sees moving toward protein sources from aquaculture as key to reducing emissions generated by land-based farming.

“The take-home message is if you eat a whole bunch of oysters, the amount of nitrous oxide released into the environment is negligible compared to [if you ate] chicken, pigs, sheep or cows,” Fulweiler said.

Kincaid has spent the past 20 years tracking the movements of water and nitrogen in Narragansett Bay. A self-described “coastal plumber,” he is building a predictive computer model to use in the state’s coastal waters. Kincaid cited a 2003 fish kill as a prime reason to examine water quality, nutrient dynamics, and algal blooms.

Low oxygenated areas in the coves, harbors and estuarine waters of Narragansett Bay have “amazingly stable” gyres, or vortexes, that move currents slowly in a clockwise direction. Kincaid and his team use Regional Ocean Modeling Systems to track these currents after accounting for tidal flows.

“We could use [this data] around aquaculture farms and predict how water flows in and out,” he said.

Nitrogen enters Narragansett Bay from the north and south. In the north, much of it comes from wastewater-treatment plants. In the south, it comes in through massive water intrusions from Rhode Island Sound, traveling through the East Passage — the channel of water between Jamestown and Aquidneck Island.

“The amount of water coming in on these intrusions is on average twice the same amount that goes over Niagara Falls every day,” Kincaid said.

The professor of oceanography said he and his research team aren’t entirely sure what else is in some of these East Passage water intrusions besides high levels of nitrogen, but has a future study planned to investigate.

David Warsh: Searching under streetlights for economic answers

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

As a young magazine writer, I was a quick enough study to recognize that, in the discussion of inflation, the bourgeoning enthusiasm for monetary analysis had loaded the dice in favor of the quantity theory of money. New World treasure, paper money, central banking: it was as if monetary policy was a force independent of whatever might be happening in the economy itself. It reminded me a famous New Yorker cartoon, a patient talking to his psychoanalyst: “Gold was at $34 when my father died… it was $44 when I married my wife… now it’s $28, but I have trouble seeing.”

I wanted to suggest a variable that might represent the perspective of real analysis, though I did not yet know the term: the conviction, as I learned Joseph Schumpeter had described it, that “all the essential phenomena of economic life are capable of being described in terms of goods and services, of decisions about them, and relations between them,” and that money entered the picture as just another a technological device. Thinking about all else besides monetary innovation that was new in the world since the 15th Century, I came up with a catch-word to describe what had changed. The Idea of Economic Complexity (Viking) appeared in 1984.

It certainly wasn’t theory: more in the nature of criticism, a slogan with so little connection to the discourse of economics since Adam Smith that it didn’t bother specifying complexity of what. But the word had an undeniable appeal. “Complexity,” I wrote, “is an idea on the tip of the modern tongue.”

Sure enough: Chaos: Making a New Science, by James Gleick, appeared in 1987; Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Chaos and Order, by M. Mitchel Waldrop; and Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos, by Roger Lewin, followed in 1992; and in the next decade, a whole shelf of books appeared, of which The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Remaking of Economics, by Eric Beinhocker, in 2006, was probably the most interesting.

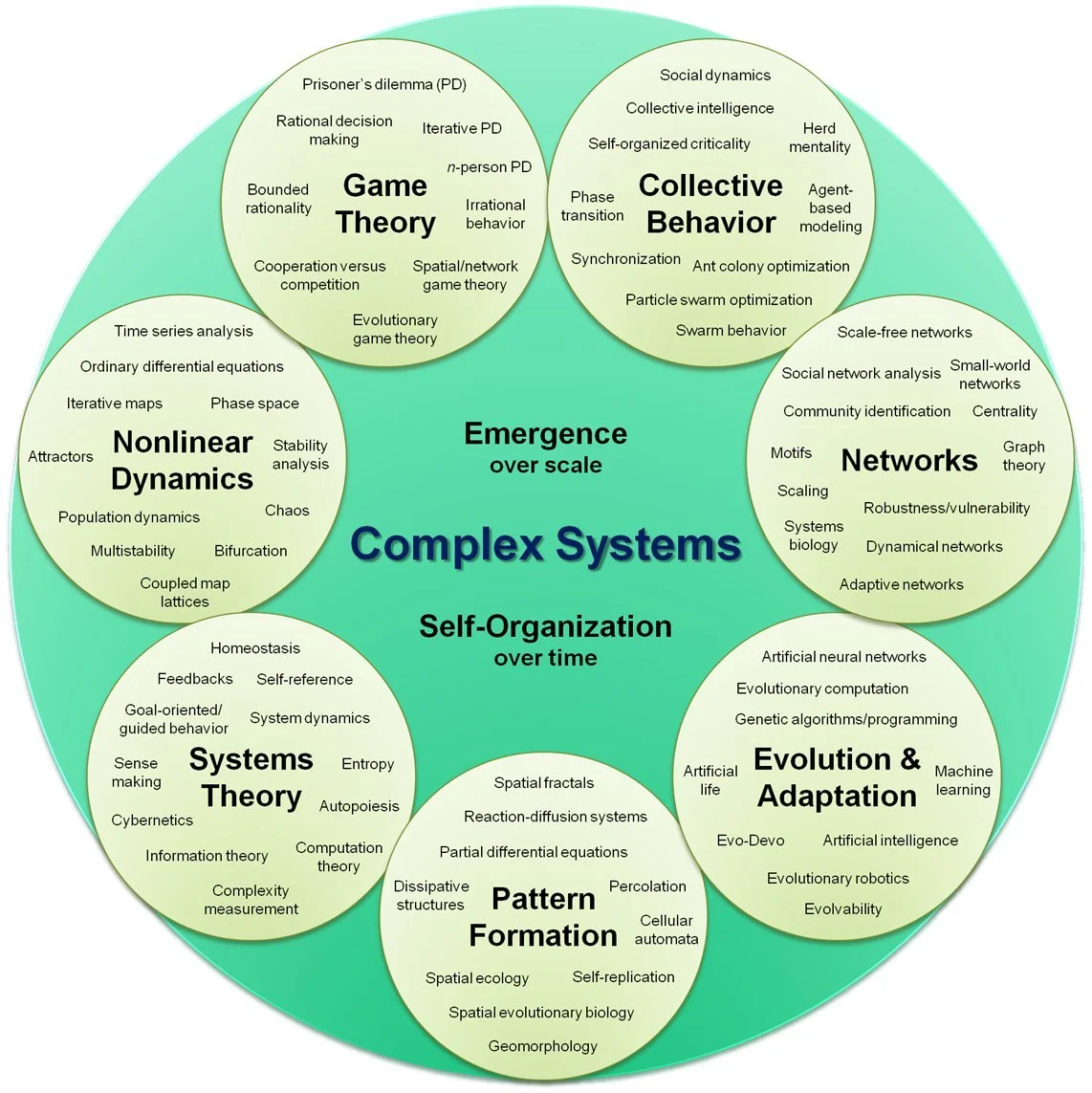

Organizational map of complex systems broken into seven sub-groups.

— Hiroki Sayama, D.Sc

But the question remained: complexity of what? The long quote-box on the back of the book jacket had put it this way:

To be complex is to consist of two or more separable, analyzable parts, so the degree of complexity of an economy consists of the number of different kinds of jobs in the system and the manner of their organization and interdependence in firms, industries, and so forth. Economic complexity is reflected, crudely, in the Yellow Pages, by occupation dictionaries, and by standard industrial classification (SIC) codes. It can be measured by sophisticate modern techniques, such a graph theory or automata theory. The whys and wherefores of our subject are not our subject here, however. It is with the idea itself that we are concerned. A high degree of complexity is what hits you in the face in a walk across New York City; it is what is missing in Dubuque, Iowa. A higher degree of specialization and interdependence – not merely more money or greater wealth – is what make the world of 1984 so different from the world of 1939.

Fair enough, for purposes of journalism. There was however something missing in my discussion: to wit, any real knowledge of structure of technical economic thought. I had come across the economist Allyn Young (1876-1929) in my reading, a little-remembered contemporary of Irving Fisher, Wesley Clair Mitchel and Thorstein Veblen, Schumpeter, and John Maynard Keynes. I classified him, with Schumpeter, as a “supply-sider,” in keeping with the controversies of the early ‘80’s, “locating in the businessman’s entrepreneurial search for markets the most profound impulse toward economic growth.” I added only that “We are coming at it from a slightly different direction is this book.”

It wasn’t until I re-read “Increasing Returns and Economic Progress” (for those who have access to JSTOR), in the Economic Journal of December 1928, that it dawned on me that it was complexity of the division of labor that I had been thinking about. A particular passage towards the end of Young’s paper brought it home.

The successors of the early printers, it has often been observed, are not only the printers of today, with their own specialized establishments, but also the producers of wood pulp, of various kinds of paper, of inks and their different ingredients, of type-metal and of type, the group of industries concerned with the technical parts of the producing of illustrations, and the manufacturers of specialized tools and machines for use in printing and in these various auxiliary industries. The list could be extended, both by enumerating other industries which are directly ancillary to the present printing trades and by going back to industries which, while supplying the industries which supply the printing trades, also supply other industries, concerned with preliminary stages in the making of final products other than printed books and newspapers. I do not think that the printing trades are an exceptional instance, but I shall not give other examples, for I do not want this paper to be too much like a primer of descriptive economics or an index to the reports of a census of production. It is sufficiently obvious, anyhow, that over a large part of the field of industry an increasingly intricate nexus of specialized undertakings has inserted itself between the producer of raw materials and the consumer of the final product.

Young, a University of Wisconsin PhD, had taught both Edward Chamberlin and Frank Knight as a Harvard professor, before accepting an offer from the London School of Economics to chair its department, at a time when LSE was looking to further distinguish itself. It was as president of Section F of the British Association for the Advancement of Science that he delivered his paper on increasing returns. Then, on the verge of returning to Harvard, he died at in an influenza epidemic. He was 52.

By the time that I re-read Young’s paper, I had met Paul Romer, a young mathematical economist then at the University of California Berkley, who had been working for years on more or less exactly the same questions that Allyn Young had raised in literary fashion fifty years before. Romer introduced me to the distinction economists made between “endogenous” and “exogenous” factors.

Endogenous were developments within the economic system; exogenous were those apparently outside, to be “bracketed” or put aside as matters the existing system hadn’t yet found ways to satisfactorily explain. Only a few years earlier, Robert Solow, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had been recognized with a Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for, among other things, his finding that as much of 80 percent of economic growth in a certain period couldn’t be explained by additional increments of labor and capital. Whatever it was, it was to be expressed as a “Residual,” exogenous to the system of supply and demand.

First in “Growth Based on Increasing Return Due to Specialization,” in 1987, then in “Endogenous Technical Change,” in 1990, Romer solved the problem, employing new mathematics he had acquired to describe it. The magic of the Residual, it turned out, was human knowledge, a non-rival good in that, unlike land, labor, or capital, it could be possessed by any number of persons at the same time. I wrote a book about what had happened; Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery (Norton) appeared in 2006. In 2018, Romer, by then at New York University, and William Nordhaus, of Yale University, shared a Nobel Memorial Prize for their work on the interplay of technological development and climate change.

I had been hit by the meatball. I understood why Early Hamilton and John Neff had so little to say to each other, why Milton Friedman and Paul Samuelson didn’t agree: they were men searching under streetlights for answers – different streetlights, separated by areas of darkness that had yet to be illuminated. I understood that economists could be trusted to continue to develop their field,

But there were still plenty of questions to be answered, including the one that had bothered me since the beginning. Why do we call rising prices “inflation?”

xxx

One of the joys of writing about the news is that you ordinarily never know where you’re going from one week to the next – reading as well, I expect. Yet from small beginnings last autumn, I have launched a mini-series about some things I have learned since publishing The Idea of Economic Complexity in 1984. Had I known at the beginning what to expect, I would have announced a series, Complexity Revisited. I do so now.

This week is the fourth installment, counting the first piece – about the 700-year wage and price index of Sir Henry Phelps Brown and Sheila Hopkins – that triggered the rest. There will be four more, eight in all. Each piece subsequent to the first is connected to something I discovered later, in the witings of Joseph Schumpeter, Charles Kindleberger, Allyn Young, Steven Shapin and Simon Schafer, Nicholas Kaldor, Hendrik Houthakker, and Thomas Stapleford.

What’s the point? It all has to do with the nature of money – how we control it, how it is accumulated, saved and disbursed. Banking is already thoroughly digitized; the digitalization of money itself looms in the future. It makes sense to go back to first principles. These have to do with central banking, it turns out, perhaps the least understood of major modern institutions of governance.

The need here to think matters through, at least a little, arose in connection with other projects underway, large and small. I don’t apologize for having undertaken the series. I’ve done it twice before over the years, each time with good results. But there is something about the weekly column that wants to stay close to the news, especially in these turbulent times. I can confidently promise not to do it again. Back to the news next month.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

— Photo by Acabashi

‘Their last asylum’

Bronze and granite monument to Samuel Adams, put up in 1880 in front of Faneuil Hall, in downtown Boston. The hall was the home of the Boston Town Meeting, on Sept. 12 and 13, 1768, an extralegal assembly held in response to the news that British troops would soon be arriving to crack down on anti-British rioting.

— Photo by Anne Whitney

“Driven from every other corner of the earth, freedom of thought and the right of private judgment in matters of conscience direct their course to this happy country as their last asylum.”

— Samuel Adams, in “Speech in Philadelphia,’’ on Aug. 1, 1776.

Samuel Adams was an American statesman, political philosopher and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, and one of the developers of the principles of American republicanism. And he served as the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’s fourth governor (1794-1797). He was a second cousin to his fellow (and less radical) Founding Father, John Adams, the second U.S. president.

Manmade and thus disposable

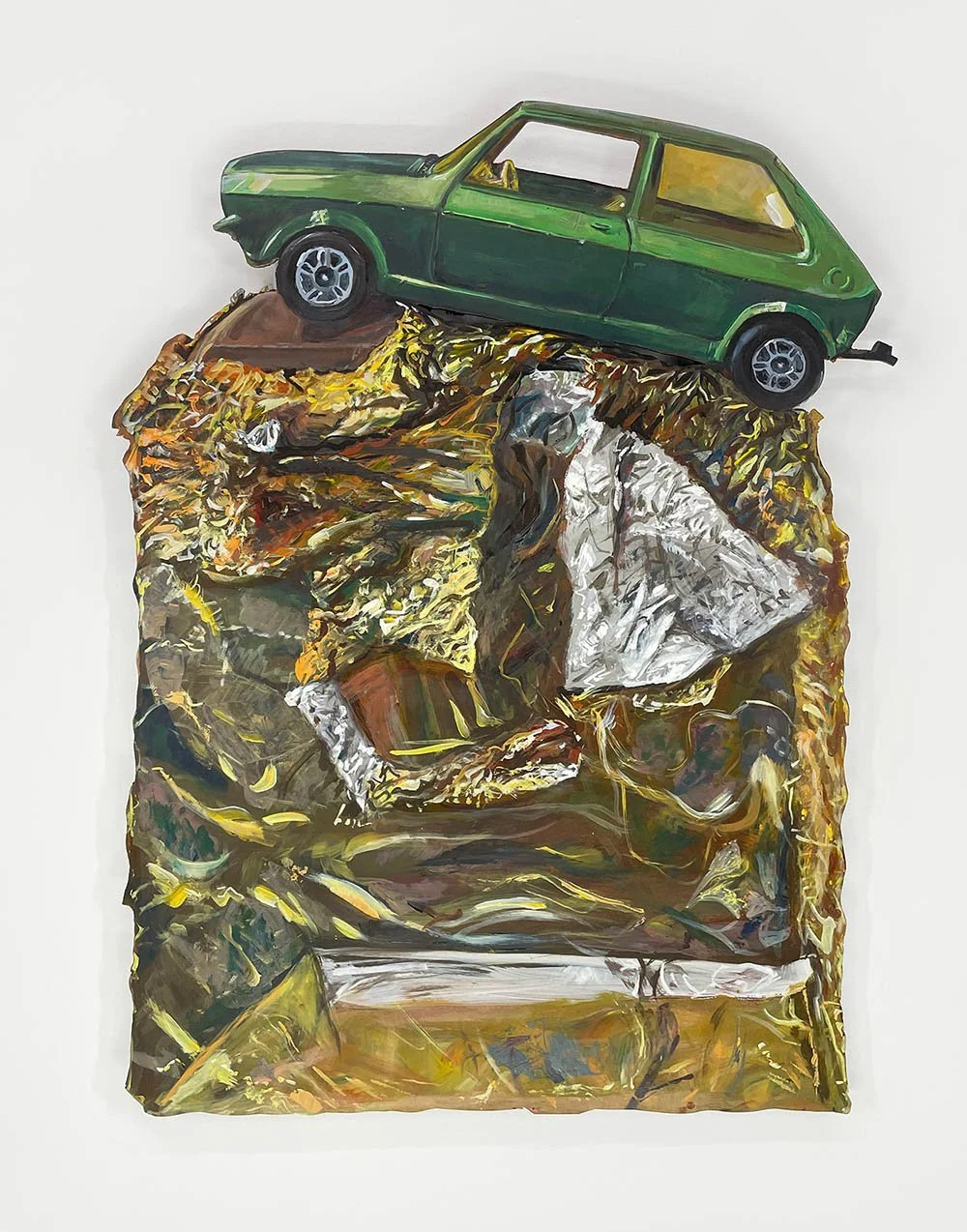

"Car and Candy Bar” (acrylic on panel), by Groton, Mass.-based Caleb Brown, in his show “Playdate,’’ at Bromfield Gallery, Boston, through May 1.

The gallery says that the show consists of still-life paintings of “personal ephemera arranged as on a child’s whim and then left behind, as though a play date has just ended.

“Cut from Masonite panels, the still lifes evoke an unfussy trompe l'oeil style.’’

Gibbet Hill in Groton. According to tradition, the name comes from an incident in Colonial times when a Native American was hung at the summit of the hill. Wikipedia: “A gibbet is any instrument of public execution, but gibbeting refers to the use of a gallows-type structure from which the dead or dying bodies of criminals were hanged on public display to deter other existing or potential criminals.’’

— Photo by John Phelan

‘Hubcaps and falling rocks’

Great Falls (at Bellows Falls, Vt.) at high flow under the Vilas Bridge, taken from the end of Bridge Street on the Vermont side, looking upriver. Route 5, not in picture, runs up the Vermont side of the river on the left.

“I left my anger in a river running highway 5

New Hampshire, Vermont, bordered by

college farms, hubcaps, and falling rocks

voices in the woods and the mountaintops’’

—From the song “Jonas & Ezekiel,’’ by The Indigo Girls

Don Pesci: Conn.’s temporary gasoline-tax cut and trying to repeal economic common sense

Major roads of Connecticut

VERNON, Conn.

The default position of Connecticut’s majority Democrats on the matter of getting and spending has not changed within the past three decades: Tax cuts, infrequently imposed, should be temporary and bravely endured, while tax increases, deployed for the most part to satisfy imperious state-employee-union demands, should be permanent.

The recent temporary suspension of Connecticut’s 25-cent-a-gallon excise gasoline tax conforms to the default position of Democrats who have controlled Connecticut’s General Assembly for the last 30 years: The tax is to be suspended – operative word – “temporarily” from April to July 1.

Connecticut Democrats, it should seem obvious, are reading from a national Democratic script.

The increase in the price of gasoline, they say, is due chiefly to the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine and the greedy oil barons.

The debate in the General Assembly on reducing Connecticut’s gasoline tax centered upon whether the reduction should be temporary or permanent.

“Rep. Sean Scanlon, a Guilford Democrat who co-chairs the tax-writing committee,” one newspaper noted, “said many constituents have been hurting from the rising prices at the pump, which was recently an average of $4.32 a gallon.

“Our constituents did not start a war in Ukraine,’' Scanlon argued. “Our constituents did not contribute to the global supply chain. ... This is a great first step that we can make to give them some affordability, some relief. ... At least we’re doing something.”

The newspaper correctly noted, “The tax cuts are possible partly because the state has large budget surpluses in two separate funds due to increased federal stimulus money and capital gains taxes from Wall Street increases, paid largely by millionaires and billionaires in Fairfield County.”

In the state Senate chamber, also dominated by Democrats, Will Haskell, of Westport, rose to the occasion. Haskell argued that the gasoline-tax cut should not be permanent because providing permanent relief would deliver a “debilitating blow’' to the state’s plans to spend millions of dollars to fix roads and bridges. The paper quoted Haskell: “Gas prices are high, but not because of taxes. It’s because of [Russian dictator Vladimir] Putin.”

The federal government – which prints money, borrows money and acquires money through excessive taxation – is flush with funds now being distributed by the Biden administration to various political receptacles, some say for political purposes. In many instances, states are using the funds to offset business slowdowns caused by, some argue, imprudent decisions made by governors and federal officials that have produced a worker shortage. Common sense tells us that if you provide a living salary to workers not to work, they will not work.

High business taxes, an increase in the supply of money flowing from private pockets to the public purse, and labor shortages have produced too few goods, resulting in inflation – too many dollars chasing too few goods.

The high price of goods and services may also be attributed to a continuing effort by progressives in the United States to repeal a central law of a free-market economy, the law of supply and demand, which holds that when demand is a constant and supply is diminished, prices on all goods and services rise. The rise in prices has less to do with the greed of billionaire CEOs than a Darwinian survival-of-the fittest-impulse in over-regulated markets centrally directed by Washington politicians. Large business can survive a large regulator drag on profits. Higher taxes and an increasing regulatory burden swamp smaller businesses and, of course, make it much easier for the larger fish to swallow the minnows.

The empty shelves in Russian stores during the good old days of the Soviet Union were attributed by underpaid “workers of the world” in Russia to central planning. In the so-called “captive nations,” the necklace of states now threatened militarily by Vladimir Putin, workers used to joke among each other, “We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.”

The Democratic Party program runs against the grain of good sense. Every worker in the United States knows that personal debt should be discharged by responsible debt holders willing to cut spending and pay down the debt.

Temporary reductions in taxes are insufficient to pay down a debt in Connecticut that has swelled over the years to about $57 billion. And given past performance, no one in the state can be certain that increased taxes will be put to such purposes by an administrative apparatus, growing daily, that had in the past raided various Connecticut lockboxes to pay for current expenses.

The solution to Connecticut’s most pressing economic problems is disarmingly simple: Enrich the state’s creative middle class by cutting taxes and regulations, pay down debt, and work hard to dissolve the entangling alliances between a tax-thirsty government and an even more tax-thirsty conglomeration of various state employee unions.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

The Mystic River Bascule Bridge, built in 1922, carries US 1 over the Mystic River in Connecticut. The famous span connects Groton with the Stonington.

A grudging month

Boston Public Garden in spring

— Photo by Rick Harris

“Poets in other climes may rhapsodize about the vagaries of April weather, its laughter and tears, but in New England the month has inspired few local bards to lyric praise of the region’s early spring weather. With eastern Canada still deep in snow and the coastal waters retaining their wintry chill, northern controls can dominate the meteorological scene with snowfalls and cold lingering through the end of the month. Yet another April might produce a southerly circulation early in the month, bringing …May flowers well ahead of schedule….”

From The Country Journal New England Weather Book (1976) by David Ludlum. New England’s climate has warmed since 1976.

‘A fine, warm affair’, but a heart stopper?

Baked beans are an ancient New England specialty.

Fish cakes, usually made from codfish, used to be a very common New England dish for all three main meals of the day.

“Traditionally the Yankee breakfast has been a fine, warm affair, a minor feast that can hold its own with any other meal. Yankees rose early (most of them still do), and the chores that had to be done while breakfast was prepared produced a happy appetite for fish cakes, baked beans and pie. The only restriction to dishes that should please a hungry man was that they had to be something kept over from the day before or possible to cook in a reasonably short time.’’

-- Sara B.B. Stamm, in Favorite New England recipes (1972)

The joys of camping

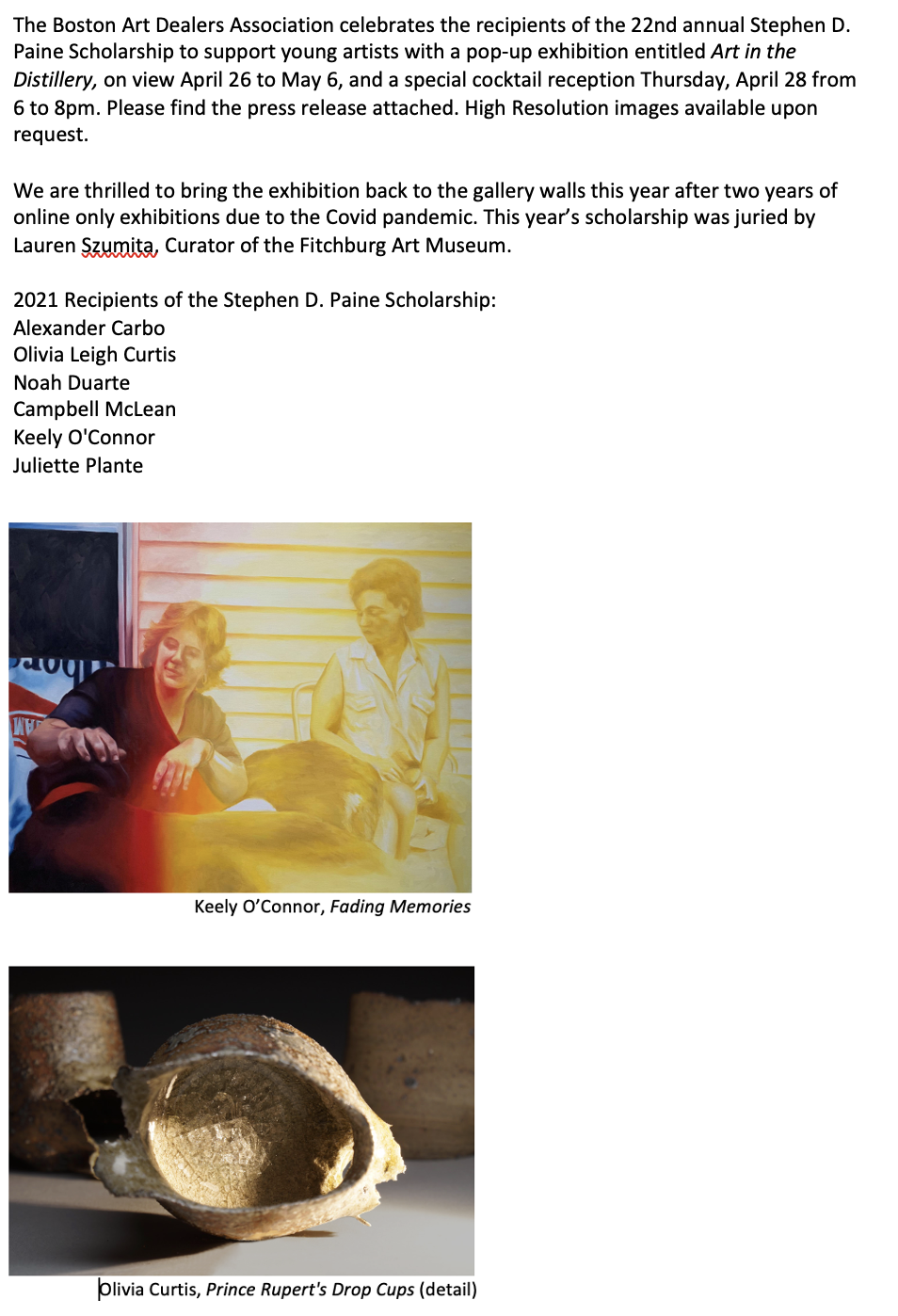

“Insomnious’’ (oil on canvas), by Eva Lewis, in her show “Eva Lewis: Disparate,’’ at LaiSun Keane Art Gallery, Boston, through May 1.

The gallery says: "Lewis's intelligently executed paintings utilize soft but saturated colors, exploring the use of light and color to evoke emotional response in the viewer. Her familiar yet dreamy settings feature subjects drawn from her own friend group from her hometown of Dayton, Ohio."

Llewellyn King: Biden's conflicted policies on natural gas; is a carbon-capture breakthrough coming?

Model of the LNG tanker Rivers. It was built in 2002 and is registered in Bermuda. Its capacity is 137,500 cubic meters of gas.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Joe Biden at war and Joe Biden at peace aren’t the same person. When it comes to the Russia-Ukraine war and energy policy, the U.S. president is severely conflicted.

Central to Biden’s strategy has been to cut off Russia’s huge revenues from exporting natural gas to Europe. He has unambiguously declared that the shortfall Europe will have in natural-gas supplies from Russia will, in time, be remedied with other sources, especially with liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports from the United States.

So far so good. But Biden has always favored the environmental vision of the left wing of his own party and its implacable resistance to all forms of carbon-based fossil fuels because of their contribution to global warming.

Europe imports one third of the natural gas it needs for electric generation, heating and other domestic uses by pipeline from Russia. Particularly vulnerable is Germany, which depends on half of its gas imports from Russia: a dependency which it has happily allowed to grow year after year.

That was worsened when Germany turned its back on nuclear, aided by its influential Greens, after Japan’s Fukushima disaster, in 2011.

Charlie Riedl, executive director of Center for LNG at the Natural Gas Supply Association, said on my weekly PBS program, White House Chronicle, it will take several years to boost U.S. LNG exports to Europe and will need substantial infrastructure investment.

The United States has six operating export LNG terminals and a seventh nearly ready to enter operation. Europe has 26 main receiving terminals and eight smaller ones. Each new U.S. terminal has a price tag of around $20 billion, Riedl confirmed. Similarly, tankers must be available and gas exporters, like Qatar, are increasing their tanker fleets.

The impediments to building new natural-gas infrastructure in the United States are formidable. On the same broadcast, Sheila Hollis, acting executive director of the U.S. Energy Association, a nonpartisan, non-lobbying group that embraces all energy, explained, “I don’t think there is any easy way to make anything happen of this magnitude in the country, regardless of what infrastructure you’re building, or which industry’s infrastructure.

She went on to say, “I do think it will remain an ongoing saga of slogging your way through the morass of regulations, both state and federal of every conceivable variety, and the strong opposition that comes from entities like financing communities and universities that may have a particular interest in reducing CO2; and because of the magnitude, it is one that will be lit on in the regulatory setting, in the judicial setting, and in the legislative setting, both state and federal, because that is the nature of the beast.”

Moreover, Hollis said, there are environmental-justice sensitivities: “Who gets the work? Where will the facilities be sited? And there will be extreme attention to environmental issues at the facilities and the pipelines.”

Biden is caught between his own plans to cut fossil-fuel use in electric supply in the nation and his commitment to Europe that the United States will be a reliable supplier of fuel for their electricity needs over the long haul.

Commitment is important to the gas industry, which is whipsawed between demands for natural gas and attempts to limit its use by obstructing development. New natural-gas infrastructure will need to operate over several decades to recover investment -- at odds with the Biden plan to reduce fossil-fuel generation in the United States by 2030 and get to net zero by 2050.

A bright spot: The industry is confident that sometime in the future, carbon can be removed from natural gas at the time of combustion. This technology is called carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) and envisages getting the carbon out of the combustion effluent before it goes into the air. It can then be used as a building material and for future gas and oil well stimulation.

According to USEA’s Hollis, the Department of Energy is working with its national laboratories and is making solid progress in perfecting the technology. Energy aficionados believe increasingly that a breakthrough is at hand.

If that is so, then Biden can shush his environmental critics and approach the future with more confidence, giving gas companies and utilities the durable assurances they need.

Meanwhile Biden is bullish on future gas in Europe and bearish on gas in the United States. As in the Johnny Mercer song, “something’s gotta give.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

And ‘about meat prices’

The Porter Square Shopping Center in 2009.

“You can’t assume anything in politics. That’s why every Saturday I walk around my district. I talk to the longshoremen in Charlestown. I listen to the people in East Boston and their concern on the airport noise. I walk down to the Star Market in Porter Square, and people tell me about meat prices.’’

— Thomas P. {“Tip”) O’Neill (1912-1994), Massachusetts congressman who served as U.S. House speaker in 1977-87.

The Rand Estate, on site of what is now Porter Square Shopping Center, 1900 or earlier.

‘Shapes of mind’

“The Layers of Clouds in Night,’’ by Hyun Jung Ahn, in her show “Rendezvous,’’ at Heather Gaudio Fine Art, New Canaan, Conn., April 2-May 7.

The gallery says:

“Born and raised in South Korea, Ahn is a multidisciplinary artist who moved to New York City in 2015 in pursuit of her second M.F.A. Her work investigates abstraction through enigmatic forms she terms ‘shapes of mind’. The cultural differences and language barriers she experienced when she moved to the United States forced Ahn to ‘quiet her mind’, as she states. Her work evolved from the figurative and representational to a reduced abstraction that economized and purified her expression. The result was a new visual language that became more hermetic and enigmatic in color and form. Although today she is mostly Brooklyn-based, she continues to straddle both cultures by maintaining a studio and teaching position in Seoul.’’

Waveny mansion in Waveny Park, in New Canaan.

Kyle Sebastian Vitale: The campus courage crisis

The Yale Law School building, erected in 1931. Modeled after the English Inns of Court, the law building is at the heart of Yale's campus and contains a law library, a dining hall and a courtyard.

— Photo by Shmitra

Via The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Journal of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Courage has become a superlative attribute in our age. Health-care workers courageously work on the frontlines of COVID-19. Ukrainian President Zelensky exhibits courage against foes of democracy. These figures risk their personal security for the benefit of others and higher ideals. Higher education, too, is newly interested in courage as a centering ideal. That’s good: We need more courage on campus these days.

What we have instead is a mistaken notion of courage. Take recent events at Yale Law School. Student protesters disrupted a bi-partisan Federalist Society panel about religious freedoms, featuring the American Humanist Association and Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF). Students quietly joined the event before ambushing it, heckling the speakers Monica Miller and Kristen Waggoner over ADF’s and the Federalist Society’s conservative positions. As the video conveys, students acted under an assumed banner of courageous support for those identifying as transsexual.

Undoubtedly, this took nerve, and I am slow to fault students who intended to act in good faith. Yet is this courage? Most will agree that courage, while complex to define, carries a quality of personal sacrifice. Clemson University’s Cynthia Pury, speaking with the Berkeley Greater Good Science Center, helpfully qualifies courage as something requiring “a noble goal, personal risk and choice.” That seems to get at our common notion of courage as something that takes both strength and sacrifice.

The Yale event featured little personal risk. Students hid behind signs and cries that freedom of speech justified their actions. Missing was the vulnerability of actual discussion, and with it, the risk of one’s views undergoing scrutiny. This was about abolishing discomfiting views, not the small sacrifice of listening to others. Those who disagreed with speakers Miller or Waggoner but were prepared to listen, showed far more courage.

Similarly disruptive events occur across college campuses elsewhere, and they look the same: group settings, much shouting and swift departure by those protesting. Student hecklers rarely face up to the reality that they may not be entirely right or that their “enemy” may not be entirely wrong, both of which involve personal risk to one’s ideals. This is anger, but it is not courage. How do we counter this instinct?

By amplifying better models of courage. Emma Camp is one. Camp wrote recently about the culture of self-censorship among students at the University of Virginia. Students like Camp feel the relentless pressure to tow the ideological line, lest they find themselves on the outs with peers. Her essay is a model of courage, energized by higher ideals, open about her beliefs and honest about her mistakes. She knew the piece would receive a mixed response, and boy was she right, yet she met criticism with poise and interest.

If there are more students like Emma Camp out there, campus culture certainly doesn’t help us find them. A recent survey from Heterodox Academy reveals that 63 percent of students feel their campus climate prevents them from expressing their beliefs on various subjects, for fear of criticism or retribution from classmates and teachers. Courage’s unique ingredient—personal risk—is uniquely threatened on campus.

In response, higher education must create campuses rooted in trust and courage—trust that we are willing to hear each other out and courage to risk our assumptions and ideas. Students are certainly not blameless here, giving in to groupthink and pressuring one another into empty activism. Yet, they are also starved for models of courageous engagement with the uncomfortable. Numerous cases record campus administrators caving to students who demand more than they offer. Faculty too are often too quick to apologize when students perceive a racist or sexist comment, rather than respond with their intentions and pedagogical beliefs.

Courage is not screaming against the things that indispose us. Courage is sharing beliefs with confidence, authenticity and flexibility. It improves campus culture by contributing more perspectives and welcoming more views in the search for truth. It also requires much: faculty building classrooms that cultivate sincere interpersonal interest, administrators modeling charitableness and tenacity, and students choosing to listen and risk putting their beliefs under the microscope.

That same Heterodox Academy survey and other available research reveal that college students are more willing to share their beliefs in high-quality interactions with people they know. Our students are quietly ready to be more courageous on campus. Let’s support the ideals and the designs that help them get there.

Kyle Sebastian Vitale (@kylesebvitale) is director of programs at Heterodox Academy, a nonpartisan collaborative of more than 5,300 professors, educators, campus administrators, staff and students committed to enhancing the quality of research and education by promoting viewpoint diversity in higher education. He writes about higher education and has taught literature and pedagogy for over a decade at Yale University, the University of New Haven, the University of Delaware and Temple University.

Paintings from walks

“Riverway” (acrylic on canvas), by Robert Baart, in his show “Land Marks,’’ at M Fine Arts Galerie, Boston, through April 30.

The paintings in this collection result from the artist's pandemic walks from Brookline Village to his Ipswich Street, Boston, studio. The gallery says: "This recent body of work continues to emphasize the importance of nature in our lives. Regardless of location—city or countryside—the natural world we encounter has a direct effect on our health and spirit."

Washington Street in Brookline Village.

MIT spinoff seeks big new energy source via drilling very deep boreholes

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) statement

BOSTON

“A Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), spinoff company, Quaise Energy, is digging into the Earth to ease fossil-fuel reliance. MIT invests in startup technology companies, including Quaise Energy, using its fund and platform, called The Engine, to commercialize world-changing technologies.

“Quaise Energy has created new technology capable of digging some of the deepest boreholes in history to reach rocks below ground and surface a kind of heavy steam that has the potential to provide enormous quantities of energy, with a goal of using this steam to run power plants.

“To dig these holes, it will require the power of a laser to cut through dense rock, and it also needs to retain its intensity over long distances. This means as the technology goes further underground, it will have to maintain its power. Another advantage is that the lasers vitrify boreholes, meaning that their heat encases the blasted rock in glass and makes the holes less likely to collapse, which has been a significant problem in getting this type of energy when past companies have tried. There are other concerns that this team with the backing of MIT is working to resolve, including reducing the chances of seismic waves because of this.

“‘By drilling deeper, hotter, and faster than ever before possible, Quaise aspires to provide abundant and reliable clean energy for all humanity,’ said Carlos Araque, a former MIT student and employee, whose new company has raised $63 million to prove its technology. ‘This could provide a path to energy independence for every nation and enable a rapid transition off fossil fuels.’’’

Kelp: Great slippery aquaculture potential

In a kelp forest

— Photo by Ggerdel

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Growing the seaweed called kelp could become an important part of Rhode Island’s “blue economy’’ in coming years. So it was heartening to read, in ecoRI News, of the enthusiasm of Azure (birth name?) Cygler about her newish company, Rhody Wild Sea Garden LLC. She’s growing kelp in Narragansett Bay’s East Passage in water leased from an oyster farmer.

Kelp is great stuff – as a highly nutritious food, as a thickener and sweetener, for cosmetics and as a fertilizer. It is also a weapon in the battle against global warming: It absorbs carbon dioxide more effectively than do trees. And it takes in the excessive nutrients that wash into the water from chemical fertilizers (ah, those lawns and golf courses!) and other manmade stuff. Further, it’s harvested in the winter, and so less likely to draw the well-lawyered opposition of, say, affluent people with summer places along the shore.

Kelp in canned salad form

That gets me thinking about the University of Rhode Island’s Bay Campus, in Narragansett, home of URI’s internationally respected Graduate School of Oceanography. The Bay Campus needs major repairs and additions if the school is to continue to do the world-class research (with economic-development rewards from that) that, with teaching, is central to its mission.

Gov. Dan McKee has proposed a $50 million bond issue for improvements at the Bay Campus for voters to decide on next November. But URI says the full cost of the needed work is $157.5 million; there’s hope that state legislators will back a bigger amount than $50 million. They should: The School of Oceanography has a major part to play in the state’s future, environmentally, economically and otherwise. That includes defense, energy and, yes, aquaculture.

Rescuing objects; Singing Beach

“Orbs and a Blackbird’’ (encaustic), by Hollandra Berube, a Manchester-by-the-Sea (Mass.) artist.

She says:

“While creating my series Orbs and a Blackbird, I expressed my love of free form work and how I gravitate towards the sense of alignment with Self and just Being and Allowing. The boldness of Blackbird explores the feeling of one’s Higher-self overseeing all that IS; enlightenment and consciousness, and plays with my personal exploration of manifesting romantic energy, Love and balance.

“Brilliant color and bold ideas are hallmarks of my work as an artist, designer and builder. Nothing is off-limits and I move fluidly between mixed media, sculpture, encaustic, and interior design. I thrive on transforming empty spaces and combining the overlooked with the unexpected.

“Using encaustic paint and power tools, I rescue, revitalize, and reinterpret objects. Like an alchemist, creating something from nothing is the essence of my work. My deepest inspiration comes from being challenged by problem solving. I love responding to a particular situation and moving it from a negative to a positive. I rely on my desire for beauty, and my pleasure of aesthetic. My work envelopes the viewer in possibilities.’’

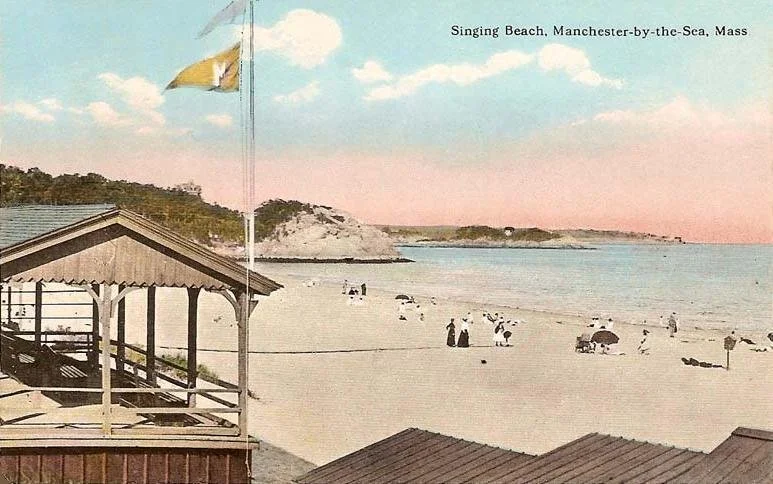

Singing Beach, in Manchester-by-the-Sea, in 1914. The strand, nearly three quarters of a mile long, is renowned for its fine white sand. When ocean bathing became popular in the late 19th Century, visitors discovered that the composition of the sand produces a “singing’’ sound when walked on.

‘To which we must return’

“It is mud season. God’s yearly reminder to us of the clay from which we rose and to which we must return, hill people and Commoners alike.’’

Howard Frank Mosher (1942-1917), novelist, in Where the Rivers Flow North. Virtually everything he wrote for publication was set in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, where he lived in Irasburg.

Panoramic view of Willoughby Notch and Mount Pisgah, in the Northeast Kingdom

— Photo by Patmac13