Vox clamantis in deserto

‘Into these hills’

In Franconia Notch in 1915. The northern part of Franconia Notch State Park is in the Town of Franconia.

”Because it is the work that is the work

you could take the world itself to mean

yourself. Into these hills you’ve taken for granite,

like the present, you could take place and be one

with the subject of your feeling arising

before you….’’

— “Tourist (Franconia {N.H.} 1986)’’, by Christopher Gilbert (1949-2007), American poet. He was an Alabama native who ended up as a Providence resident.

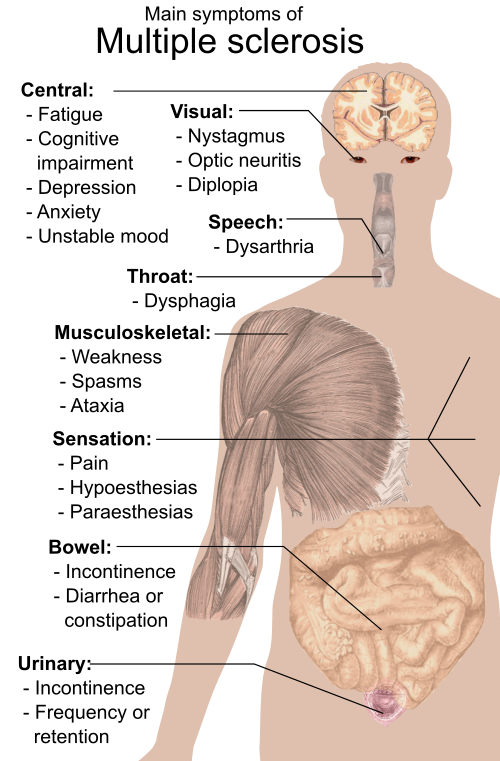

Melissa Bailey: West Nile Virus loves global warming

Global distribution of the West Nile Virus. There have been many cases in southern New England.

“West Nile Virus is a really important case study” of the connection between climate and health.

—Dr. Gaurab Basu, a primary-care physician and health-equity fellow at the Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment at Harvard’s public health school.

Michael Keasling, of Lakewood, Colo., was an electrician who loved big trucks, fast cars and Harley-Davidsons. He’d struggled with diabetes since he was a teenager, needing a kidney transplant from his sister to stay alive. He was already quite sick in August when he contracted West Nile Virus after being bitten by an infected mosquito.

Keasling spent three months in hospitals and rehab, then died on Nov. 11 at age 57 from complications of West Nile Virus and diabetes, according to his mother, Karen Freeman. She said she misses him terribly.

“I don’t think I can bear this,” Freeman said shortly after he died.

Spring rain, summer drought and heat created ideal conditions for mosquitoes to spread West Nile through Colorado last year, experts said. West Nile killed 11 people and caused 101 cases of neuroinvasive infections — those linked to serious illness such as meningitis or encephalitis — in Colorado in 2021, the highest numbers in 18 years.

The rise in cases may be a sign of what’s to come: As climate change brings more drought and pushes temperatures toward what is termed the “Goldilocks zone” for mosquitoes — not too hot, not too cold — scientists expect West Nile transmission to increase across the country.

“West Nile Virus is a really important case study” of the connection between climate and health, said Dr. Gaurab Basu, a primary-care physician and health-equity fellow at the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at Harvard’s public-health school.

Although most West Nile infections are mild, the virus is neuroinvasive in about 1 in 150 cases, causing serious illness that can lead to swelling in the brain or spinal cord, paralysis, or death, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People older than 50 and transplant patients like Keasling are at higher risk.

Over the past decade, the U.S. has seen an average of about 1,300 neuroinvasive West Nile cases each year. Basu saw his first one in Massachusetts several years ago, a 71-year-old patient who had swelling in his brain and severe cognitive impairment.

“That really brought home for me the human toll of mosquito-borne illnesses and made me reflect a lot upon the ways in which a warming planet will redistribute infectious diseases,” Basu said.

A rise in emerging infectious diseases “is one of our greatest challenges” globally, the result of increased human interaction with wildlife and “climatic changes creating new disease transmission patterns,” said a major United Nations climate report released Feb. 28. Changes in climate have already been identified as drivers of West Nile infections in southeastern Europe, the report noted.

The relationship between lack of rainfall and West Nile Virus is counterintuitive, said Sara Paull, a disease ecologist at the National Ecological Observatory Network in Boulder, Colo., who studied connections between climate factors and West Nile in the U.S. as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of California-Santa Cruz.

“The thing that was most important across the nation was drought,” she said. As drought intensifies, the percentage of infected mosquitoes goes up, she found in a 2017 study.

Why does drought matter? It has to do with birds, Paull said, since mosquitoes pick up the virus from infected birds before spreading it to humans. When the water supply is limited, birds congregate in greater numbers around water sources, making them easier targets for mosquitoes. Drought also may reduce bird reproduction, increasing the ratio of mosquitoes to birds and making each bird more vulnerable to bites and infection, Paull said. And research shows that when their stress hormones are elevated, birds are more likely to get infectious viral loads of West Nile.

A single year’s rise in cases can’t be attributed to climate change, since cases naturally fluctuate by year, in part due to cycles of immunity in humans and birds, Paull said. But we can expect cases to rise with climate change, she found.

Increased drought could nearly double the number of annual neuroinvasive West Nile cases across the country by the mid-21st Century, and triple it in areas of low human immunity, Paull’s research projected, compared with averages from 1999 to 2013.

Drought has become a major problem in the West. The Southwest endured an “unyielding, unprecedented, and costly drought” from January 2020 through August 2021, with the lowest precipitation on record since 1895 and the third-hottest daily average temperatures in that period, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration report found.

Spring rain, summer drought and heat created ideal conditions for mosquitoes to spread the West Nile virus throughout Colorado last year. West Nile killed 11 people and caused 101 cases of neuroinvasive infections in Colorado ― the highest numbers in 18 years.

“Exceptionally warm temperatures from human-caused warming” have made the Southwest more arid, and warm temperatures and drought will continue and increase without serious reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, the report said.

Ecologist Marta Shocket has studied how climate change may affect another important factor: the Goldilocks temperature. That’s the sweet spot at which it’s easiest for mosquitoes to spread a virus. For the three species of Culex mosquitoes that spread West Nile in North America, the Goldilocks temperature is 75 degrees Fahrenheit, Shocket found in her post-doctoral research at Stanford University and UCLA. It’s measured by the average temperature over the course of one day.

“Temperature has a really big impact on the way that mosquito-transmitted diseases are spread because mosquitoes are cold-blooded,” Shocket said. The outdoor temperature affects their metabolic rate, which “changes how fast they grow, how long they live, how frequently they bite people to get a meal. And all of those things impact the rate at which the disease is transmitted,” she said.

In a 2020 paper, Shocket found that 70 percent of people in the U.S. live in places where average summer temperatures are below the Goldilocks temperature, based on averages from 2001 to 2016. Climate change is expected to change that.

“We would expect West Nile transmission to increase in those areas as temperatures rise,” she said. “Overall, the effect of climate change on temperature should increase West Nile transmission across the U.S. even though it’s decreasing it in some places and increasing it and others.”

Janet McAllister, a research entomologist with the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, in Fort Collins, Colo., said climate change-influenced factors like drought could put people at greater risk for West Nile, but she cautioned against making firm predictions, since many factors are at play, including bird immunity.

Birds, mosquitoes, humans and the virus itself may adapt over time, she said. For instance, hotter temperatures may drive humans to spend more time indoors with air conditioning and less time outside getting bitten by insects, she said.

Climate factors like rainfall are complex, McAllister added: While mosquitoes do need water to breed, heavy rain can flush out breeding sites. And because the Culex mosquitoes that spread the virus live close to humans, they can usually get enough water from humans’ sprinklers and birdbaths to breed, even during a dry spring.

West Nile is preventable, she noted: The CDC suggests limiting outdoor activity during dusk and dawn, wearing long sleeves and bug repellent, repairing window screens, and draining standing water from places like birdbaths and discarded tires. Some local authorities also spray larvicide and insecticide.

“People have a role to play in protecting themselves from West Nile Virus,” McAllister said.

In the Denver suburbs, Freeman, 75, said she doesn’t know where her son got infected.

“The only thing I can think of, he has a house, they have a little baby swimming pool for the dogs to drink out of,” she said. “So maybe the mosquitoes were around that, I don’t know.”

Melissa Bailey is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Fine art to benefit Ukrainians

Left: work by Jennifer Okumura; middle: Vicki Kocher Paret; right: Nora Charney Rosenbaum

Artists at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, have come together to offer works for sale to benefit the Ukrainian people.

The gallery says:

“Let our degrees of hope and peace become legitimizing solidarity banners for Ukraine and 'anyone' who suffers in any corner of the world. A sense of unity reassures us that the world is a pleasant place underneath human complication. All profits are going toward Ukrainian relief.’’

David Warsh: Inflation: Cost push or too much money?

U.S. inflation 1910-2018.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

From the beginning, the thing that puzzled me was the way the experts talked past each other, or, more frequently, didn’t talk at all.

I explained last autumn how a magazine assignment in 1975 immersed me in the ‘70s debate about inflation and led me to 700-year index of wages and prices in England. An unreversed “price revolution” in the sixteenth century was its central feature. Immediately I had turned to rival experts on the period, both emeritus professors at the University of Chicago. As I wrote in November,

It turned out that the facts of the price revolution were well-established, and had been understood in a certain way since Jean Bodin, in 1556, first pointed to the influx of New World gold and silver.

Earl J. Hamilton (1899-1989) published “American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, 1501-1650’’; John Nef (1899-1988) had produced “The Rise of the British Coal industry’’, “Industry and Government in France and England 1540-1640,’’ and “War and Human Progress: an essay on the rise of industrial civilization.’’

Here were champions on opposing sides of the long-running argument about the price revolution. Some years later I learned that Joseph Schumpeter in his monumental History of Economic Analysis had characterized the difference of approach as between monetary and real analysis. I was dimly aware the gulf existed because I had began learning economics by reading two little books published in the 1920s, before John Maynard Keynes entered the debate: Money, by Sir Dennis Robertson, and Supply and Demand, by Hubert Henderson.

Schumpeter’s dichotomy was comforting because it periodized the controversy. Monetary analysis had thrived in the 17 and early 18th centuries, he had written; then, starting with Adam Smith, real analysis of supply and demand had eclipsed money for well over a century.

By 1975, the argument had again become front-page news. Inflation was surging. Why? Was the Federal Reserve Board imprudent in its conduct of monetary policy? Or were “cost-push” factors, OPEC price hikes and costs of its America’s Great Society and its Vietnam War forcing the hand of the Fed?

Alas, neither Hamilton nor Nef were of much use in writing about the issue in the present day. Both men had been born in 1899. Hamilton was a member of the university’s famous department of economics; Nef, a cultural historian. Only later did I come to understand what was implied by the distinction.

Hamilton had definitely won whatever debate existed between the two. As his department colleague Donald McCloskey wrote a few years later, “Various attempts to revise his history of prices (attaching it to population, for instance) have had difficulties with the sheer mass of evidence that Hamilton had accumulated, Kepler-like.”

Nef, orphaned son of a beloved Chicago professor, ward of another, married a pineapple heiress, and had gone on to write The Conquest of the Material World, in 1964, and, in 1973, a very beguiling The Search for Meaning: autobiography of a non-conformist.

More to the point, though, professional economics had moved on, dramatically. A new Nobel Prize in Economics had been established, first awarded in 1969. Paul Samuelson, a Keynesian (that being the new name that real analysis had acquired), had won the prize its second year, for “raising the general analytical and methodological level in economic science.”

And in 1976, Milton Friedman was recognized “for his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history, and theory; and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy” – that is, for monetary analysis.

I wrote a Forbes cover story, in March 1975, taking note of the unreversed nature of 17th Century price explosion, venturing that it seemed unlikely that deflation, if it occurred, would return price levels to those that prevailed at the beginning of the 20th Century.

Like most journalists untrained in economics, I was partial to the cost-push explanation. Those OPEC price increases weighed heavy in the balance, it seemed to me. Moreover, the mid-’70s saw the beginning to the tax revolt: maybe the unmistakable growth of government since the ‘30s had something to do with it: There were new social programs, nuclear weapons, and rockets to the moon.

Reflecting on the similarities between the 16th and the 20th centuries, I was more intrigued by the emphasis the historian Nef had placed on developments in industry, government, and warfare, than by the changes in the quantity of money that had inarguably taken place, new world treasure then, and central banking now.

Mainly I was struck by the extent to which monetary analysis simply ignored the developments in the real sector that so interested Nef. Instead, monetarists (we were beginning to call them that) pursued their interests in money with apparently no thought for developments “on the ground” and banking. As for Hamilton, I thought of Albert Einstein rather than Johannes Kepler: Einstein had famously asserted, “It is the theory which decides what we can observe.” I had only just begun to read Milton Friedman’s work.

What was needed, I thought, was a theory real events of generality equal to that of the quantity theory, one which that might somehow cover all the ad hoc explanations usually advanced to explain rising prices. Together with a colleague, Lawrence Minard, I persuaded the Forbes editor, James Michaels, to let us prepare a longer piece to say as much. “Growing crops don’t make the sun shine” was a phrase we bandied about freely in those days.

It took some time. Not until other November 1976, a month after Friedman’s recognition was announced, did our lengthy article appear, under the headline “Inflation Is Now Too Important to Leave to the Economists.” A line from a Clark Gable film served as the article’s MacGuffin: “What do you mean they can’t pay more taxes? Tell them to put up the price of beans!” I wince now to see the headline in print, but the story won a Loeb award the next year, and Minard’s career and mine were launched.

There were parts of the argument that first piece made that Minard and I didn’t like. The tax angle was too acute; other angles we had come up with were missing. I persisted; Michaels remained receptive: ten months later Part Two appeared: “The Great Hamburger Paradox: An investigation into how economics went astray” (Wince again)!

This time I was “the author.” The MacGuffin was the contrast between a heavily-staffed an extensively-decorated restaurant with a fancy menu and a hamburger stand. That distinction conveyed well enough the difference between the 16th Century, when an ordinary householder was fortunate to possess a bowl and a spoon, and the 20th. The paradox was the way the labor cost of a hamburger had plummeted over centuries during which its money price continued to rise. This was a proposition about the importance of real factors: I ignored economists’ highly developed framework of supply and demand and conjured a nascent theory of “economic complexity,” employing an intuitively appealing but analytically empty word to connote the difference between degrees of development.

In terms of a restaurant menu, I wrote, the problem might be better understood as the bundling together of various costs, conflation of many costs, rather than the inflation of single price. Wordplay! This was very far from economics, and it wasn’t history, either. It was economic journalism, pure and very simple.

Then came the supply-siders, the “Mundell-Laffer hypothesis” and all that, with their emphasis on tax cuts and their preoccupation with economic growth, which they called an increase of “aggregate supply.” The influence of Steve Forbes, a future presidential candidate, grew at the magazine that his grandfather had founded and his father ran. After I was unable to get a story about James Buchanan, a future Nobel laureate, onto the magazine’s story list, I left for the library and the newspaper business. I had begun to specialize, and for the next forty years, I grew more interested in the economics profession and closer to it with every passing year.

All this came back recently as I browed through A Financial History of Western Europe, by Charles Kindleberger, in connection with another matter. I came across a section on the price revolution. It turns out that prices may have been rising in Europe for decades before the voyages of discovery got underway. The mines of central Europe yielded relatively little gold; silver was draining off to pay for spices imported on camels from the East; Henry the Navigator’s Portuguese sailors were able to sail south to the gold coast of Africa thanks to the invention of fore-and-aft rigging of sails, the stern rudderpost, and the compass; and that Columbus had been sent into the unknown in search of gold. (His diary mentions it 65 times in a voyage of less than a hundred days.) Kindleberger wrote,

Since [Earl] Hamilton’s book came out in 1934, something of a question has arisen whether the discovery of South America produced a price revolution de novo or whether it merely supported one already underway. The argument is a familiar one that we still encounter a number of times – in the debate between the banking and currency schools in nineteenth century England; between those who blame the first Great Depression represented by the fall in prices between 1873 and 1896 on the slowdown of the rate of increase in gold stocks and demonetization of silver, and those who ascribe it to real factors; and again in the explanation of the German inflation after World War I, held by monetarists to be due to simple over-production of money, and by their opponents to a complex set of real factors, including reparations, restocking, speculation, and the like….

The main a priori attack on the price revolution rests on the belief that, apart from the short run when money may be inelastic and halt a boom, money adjusts to trade rather than trade to money as the quantity theory would have it. .. If a clear-cut choice must be made between real factors and the quantity theory of money, this goes to the heart of the issue. But both explanations can be right and leapfrog one another. the bullion famine of the fifteenth century led to a frantic search for money’ the discovery of copious quantities of silver, plus debasement, and perhaps dishoarding and the coinage of plate, supported and extended the price rise which would otherwise had to reverse itself or lead to the development of money substitutes, as happened later. Clearly silver and war leapfrogged, and war is one of the greatest strains of resources and contributors to inflation.

I read the passage twice. Kindleberger’s compression of real and monetary explanations forcefully reminded me of the single most important lesson I had learned from covering professional economics in the fifty years since I wrote those adolescent articles for Forbes.

That clear-cut choice doesn’t have to be made, at least not when considered in the context of the sweet fullness of science and time. It is enough to expect that young economists will continue to do their work. “Inflation,” if that is what it is, is too important not to leave to economists. More on how I learned that lesson next week..

. xxx

Meanwhile, the best article I read last week on Russia’s war in Ukraine is “How to Make Peace with Putin: The West must move quickly to end the war in Ukraine’’, by Thomas Graham and Rajan Menon. First time Foreign Affairs readers may see it for free, I believe.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.

Chris Powell: Judge Jackson flunks the ‘what is a woman’ test; school daze; United Robots’ mystery building

Graphic by F l a n k e r

MANCHESTER, Conn.

President Biden nominated Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court to fulfill a campaign promise to give the court its first Black woman. But this week Jackson told the Senate Judiciary Committee that she can't define "woman" because "I'm not a biologist."

So how could the president have been so sure as to what constitutes a woman? He's no biologist either.

And how could the Democratic senators supporting Jackson, also no biologists, be so sure even as they are trying to push her through the confirmation process before her judicial and political philosophies are explored too much?

When the hearing on Jackson's nomination began, "woman" was in the dictionary, and had been for a long time.

But Jackson's evasion on the woman question was a strong hint that if she makes it to the court she will assist the extreme political left in promoting transgenderism and erasing any recognition of gender differences, particularly in regard to women in sports.

Of course, for many years all Supreme Court nominees have been evasive about their views on legal and political controversies. But this evasion never has been taken as far as Jackson took it this week.

The Senate should not accept such evasion. It should tell the president that if he wants to nominate a Black woman for the court, he should find one who at least isn't afraid to admit knowing what a woman is.

Hamden (Conn.) High School . The school’s main building was built in 1935 and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The lobby has murals showing scenes from Hamden's history.

— Photo by Streetsim

According to a Rasmussen poll this week, 58 percent of likely U.S. voters think that the public schools are getting worse, with only 13 percent thinking that they are improving.

Of course, the virus epidemic's interruption of schooling has damaged education terribly. But education already had been declining for years and is probably even worse than the 58 percent in the poll believe. A report in the New Haven Independent this week may not have been surprising but still should have been horrifying.

Quoting the city school system's data, the Independent reported that the performance of 45 percent of New Haven students is two grades behind where it should be and the performance of another 44 percent of students is one grade behind. Only 11 percent of New Haven students are performing at grade level.

Since most of the city's children are fatherless and impoverished, New Haven is worse in this respect than Connecticut generally, but statewide student performance should horrify as well. The last time Connecticut's high school seniors were formally tested for subject proficiency was in 2013 by the National Assessment of Educational Progress. While Connecticut's seniors performed best in the country, half still had not mastered high school English and two-thirds still had not mastered high school math.

Even so, contrary to the Rasmussen poll, most people in Connecticut seem satisfied with their public schools. At least there is no movement to improve schools academically or seriously examine student performance.

Maybe opinions about schools are like opinions about Congress, where most people think that Congress is corrupt and taking the country in the wrong direction even as most people like their own members of Congress

After all, there's some comfort in thinking that while schools are declining generally, one's local schools are still great and that, as in Lake Wobegon, all local students are above average. Such thinking relieves parents of any responsibility to take note of public education's transition from academic learning to "social and emotional learning" with a dollop of political indoctrination -- schooling without the inconvenience of proficiency-test scores.

xxx

Connecticut's Hearst newspapers this week published a remarkable news item produced by an outfit called United Robots, whose computer programs process raw data and put it into prose.

This particular item, drawn from property records, said a "spacious and historic house" in Bridgeport with three stories, 3,700 square feet, seven bedrooms, three bathrooms, and a detached garage had been sold for a mere $2,000. A photograph showed the house looks intact and secure.

But the "robots" didn't explain the low price, so incongruous amid Connecticut's housing shortage. Bridgeport is a troubled city but residential property there is not worthless. There must be a reason for the giveaway price of that house but the "robots" apparently lack the curiosity of a live reporter.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Rachael Conway: Meeting looks for ‘equitable pandemic recovery’ at N.E. community colleges

Main entrance to Bunker Hill Community College, in Boston’s Charlestown section.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

Rather than return to the pre-COVID-19 state of affairs, policy change is needed to strengthen each leg of the “three-legged stool” of community college success: students’ financial stability, learning inside the classroom, and wraparound support services on campuses, Bunker Hill Community College President Pam Eddinger told the New England Board of Higher Education’s Legislative Advisory Committee (LAC) last week.

The LAC, comprising state lawmakers who are delegates to NEBHE and a few additional sitting legislators from each state, has been convening twice a year since 2013, with each LAC meeting featuring national and regional experts on a pressing higher-education topic.

On March 14, NEBHE hosted its first in-person pandemic-era LAC meeting since 2019 at Lasell University in a hybrid format, with some attendees and panelists joining via Zoom. The first half of the LAC meeting featured a panel discussion on “Doing the Most with the Least: How State Policymakers can Support Wellbeing, Belonging and Success at Community Colleges for an Equitable Pandemic Recovery.”

Panelists included Eddinger, along with: Sara Goldrick-Rab, award-winning author, professor and founder of the Wisconsin HOPE Center for College, Community, and Justice; Linda García, executive director of the Center for Community College Student Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin; Alfred Williams, president of River Valley Community College, in New Hampshire; Audrey Ellis, director of institutional effectiveness at Northern Essex Community College, in Massachusetts; and Eudania Aquino, a Northern Essex Community College Student Ambassador. Joining the meeting in-person, Ellis and Aquino spoke powerfully about Northern Essex’s new Student Ambassador program, a peer-to-peer mentoring program created during the pandemic to foster belonging on the campus as most students had to shift to online learning.

The second part of the LAC meetings offer a colorful snapshot of legislative session updates in the six states, giving lawmakers an opportunity to learn and share models with one another.

The panel discussion and legislative updates yielded rich discussions about challenges and opportunities in postsecondary education facing the region after two years of COVID. Here are five takeaways from the spring 2022 LAC meeting:

1. New England states should look beyond traditional avenues of financial aid to support community college students. Community colleges serve the majority of the nation’s low-income, working and parenting students. These students have much to gain from earning a high-quality college credential. While many New England states administer some form of need-based financial aid, even the lowest-income students still face significant gaps in college affordability, particularly if they are enrolled part-time (as are roughly two-thirds of community college students). Goldrick-Rab advocated for federal emergency aid to become permanent, and urged New England states to follow the lead of states like Wisconsin, Minnesota and Washington, which have instituted state-based emergency funding to ensure that students do not stop-out of college due to being short, say, $300 (a seemingly manageable obstacle but enough to derail an education). She also discussed installing specialists on college campuses dedicated to connecting students to existing public benefits, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

2. Community colleges were struggling to serve students before COVID, and the pandemic added stress to an already-strained system. Eddinger of Bunker Hill in Massachusetts did not mince words: “pre-COVID is no better than post-COVID.” The change, in her words, came from seeing what happened when “we put community college systems through the stress-test” of COVID. Everything—resources, staff, materials and time—“was short, and families were backed up against the wall.” Williams noted that his River Valley Community College serves primarily rural and female students. He underscored his students’ ongoing need for support in the areas of internet connectivity, food and child-care services.

3. Federal CARES funding supported programming at community colleges temporarily, but states must invest in permanently supporting these institutions and their students. Eddinger described federal dollars as “patching a hole.” Ellis outlined how temporary funding from the federal CARES Act allowed Northern Essex Community College to create its Student Ambassadors program, which pays students to serve as peer mentors for students identified as at risk of not persisting. Aquino elaborated on her experience as a Student Ambassador, stating that part of the program’s success comes from its recognition that students benefit from persistent communication and various modes of outreach. García of Texas added that her Center for Community College Student Engagement found that students in danger of not persisting—such as men of color, one of the sector’s most vulnerable groups—felt most connected to their institutions when professors and staff knew their names, helped them establish a long-term plan for their time at the community college, and identified potential barriers to their success. Eddinger remarked on a temporary program at Bunker Hill that provided a small stipend to students in addition to covering tuition and fees, noting, “We realized that it’s not about being able to pay for school. It’s about being able to pay for life.” All of these proven interventions require investing more dollars into community colleges.

4. Faced with declining enrollment, several New England states are looking at college mergers. Connecticut state Sen. Derek Slap (D.-West Hartford), who chairs the state’s Higher Education & Employment Advancement Committee, noted that the state’s General Assembly is moving forward with its plan to consolidate the state’s 12 community colleges into one college with multiple campuses, making it the fifth largest community college in the country. He remarked that the bill has been controversial; some stakeholders are worried that the move will erase the individuality of campuses. Additionally, New Hampshire state Sen. Jay Kahn (D.-Keene) provided an update that lawmakers in New Hampshire are moving ahead with the merger of Granite State College with the University of New Hampshire. Massachusetts state Rep. Jeffrey Roy (D.-Franklin) remarked that the state passed a law in 2019 offering an off-ramp to closing institutions. In the wake of sharp enrollment declines during Covid, mergers represent one method that New England states are embracing to keep public colleges afloat.

5. Every state in the region is working on various efforts to improve college access and affordability. Lawmakers at the March 14 LAC meeting told the group that the Connecticut and Massachusetts legislatures recently pursued bills that address food insecurity on college campuses. Connecticut aims to expand funding for first-time students of its free community college program with additional resources this legislative session. New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Connecticut have introduced legislation supporting student mental health on college campuses. Massachusetts Rep. Patricia Haddad (D.-Somerset), the NEBHE chair, discussed the legislature’s push to expand college access to students with developmental disabilities and autism. The Massachusetts and Connecticut legislative representatives also remarked on their states’ student-debt reimbursement initiatives, which would primarily focus on loan forgiveness for human services and health-care workers.

Look for similar themes around the region in NEBHE’s Legislative Session Summary report outlining current post-secondary and workforce development bills in the six New England states.

Rachael Conway is a NEBHE policy and research consultant who manages the LAC.

Always busy

“Grandma’s Hands” (encaustic with embedded photo on raised panel), by Oty Merrill.

Ms. Merrill says:

“Though I am surrounded by magnificent landscapes and brilliant natural light on the coast of Maine where I live and work, I tend to turn inward when making art, drawing on memories, travels and emotions. Through color, texture and often embedding photos and other materials into the surfaces of my work, I lean towards semi-abstract and interpretive imagery in my compositions. I admire the works of artists such as Harold Garde (of Maine), Milton Avery, Marsden Hartley and Mary Cassatt. You might see their influences in my work. I strive to be honest, original and hopefully a little unique, both in my artwork and my life.’’

‘There be dragons’

The Babcock House in Charlestown, built in the late 17th or early 18th Century.

—- Photo by JERRYE & ROY KLOTZ, M.D.

The town’s Quonochontaug section had an iron-mining operation financed by Thomas A. Edison in the 1880s. There were iron particles in the form of black sand on the beach there that could be separated out with magnets and melted to produce iron. But the venture collapsed after cheaper iron was later discovered.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

For such an amusingly tiny place, Rhode Island has intense localisms. Consider Kevin Gallup’s remarks. He’s a former police officer and now director of the Emergency Management Agency in Charlestown, in the exurban south of the state.

Mr. Gallup ominously warned, in comments about PVD Food Truck Events coming to Charlestown, that “things morph’’ and town residents “might not appreciate” having people from Providence come to town for events.

“If we’re going to have people showing up from Providence and hanging out that we don’t know…along with our children…some people aren’t going to appreciate that and I can tell you that for a fact. So you’re going to need that police detail. Sorry the world needs to be this way, but these things need to be thought out.”

There’s a long tradition of seeing cities as a source of menace, including in a “city state’’ such as Rhode Island. Do Charlestown people feel safer with visitors from smaller city New London, Conn., 34 miles from Charlestown, than with people from Providence, 48 miles away?

Remember those old maps that had the Latin phrase “hic sunt dracones” (“there be dragons”) for dangerous and/or unexplored regions? One wonders how familiar Charlestown people are with the capital of their state, and how many would say they’re all too familiar with it. People can be very provincial around here, and I’ll bet plenty of people from South County have never been to Providence.

Quonochontaug Pond.

‘From sea’s slime’

The town on Nantucket Island, when it was still called Sherburne, in 1775.

“Here in Nantucket, and cast up the time

When the Lord God formed man from the sea's slime

And breathed into his face the breath of life,

And blue-lung'd combers lumbered to the kill.’’

— From “The Quaker Graveyard at Nantucket,’’ by Robert Lowell (1917-1977)

Well-papered Edwardian Boston

Boston’s “Newspaper Row’’ in 1910, when the city had seven daily papers.

The University of Maine’s ‘factory of the future’

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) message

“The University of Maine has been approved for $35 million in funding to build a new digital research laboratory. These funds were made possible under the omnibus spending bill that President Biden recently signed into law last week. This facility is an initiative of UMaine’s Advanced Structures and Composites Center and is a “factory of the future,” according to UMaine. It is being created to advance “large-scale, bio-based {material from living or once-living sources} additive manufacturing,” using technologies such as artificial intelligence and 3D printers.

“The cost of building this facility is expected to total $75 million. According to the university, the center’s new capabilities could lead to technology development in the affordable-housing industry, clean energy, transportation industry and more.’’

Llewellyn King: We must face the fact that world crises in food, inflation and energy require tough decisions and new thinking

Messengers going to Job, each with bad news.

— 1860 woodcut by Julius Schnorr von Karolsfeld

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is a rough road ahead for the world and our political class isn’t leveling with us.

As Steve Odland, president and CEO of The Conference Board, one of the nation’s premier business-research organizations, said in a television interview, serious inflation will continue at least until 2024, and longer if things continue to deteriorate with supply-chain crises and the war in Ukraine.

Particularly, Odland, who also serves as a director of General Mills Inc., fears a global food crisis with famine in Africa and many other vulnerable places if Ukrainian farmers don’t start seeding spring crops to start this year’s harvest. Already, Ukraine – once known as one of the world’s breadbaskets -- has cut off exports to make sure that there is enough food for their own people, as war rages.

Odland sees U.S. inflation continuing at 7 to 8 percent for several years at best. But his primary worry is global food supplies, as countries face a crisis of new and frightening proportions.

His second worry is stagflation. If the rate of productivity falls below 3 percent, “then we will have stagflation,” Odland told me during a recording of White House Chronicle, on PBS, the weekly news and public affairs program I produce and host.

Odland faults the Federal Reserve for being timid in raising interest rates to counter inflation.

I fault the political class for not leveling with us – both parties. As we are in a state of perpetual election fervor, we are also in a state of perpetual happy talk. “Get the rascals out, and all will be well when my band of happy angels will fix things.” That is what the political class says, and it is a lie.

We are in for a long and difficult period which began with the pandemic that disrupted supply chains and set off inflation, and now the war in Ukraine has compounded that. Supply chains won’t magically return to where they were before COVID-19 struck, and more likely they will have further constrictions because of the war. New supply chains need to be forged and that will take time.

For example, nickel, which is used in the batteries that are reshaping the worlds of electricity and transportation and for stainless steel, will have to come from places other than Russia. At present, Russia supplies 20 percent of the world’s voracious appetite for high-purity nickel. Opening new mines and expanding old ones will take time.

The world’s largest challenge is going to be food: starvation in many poor countries and high prices at the supermarkets in the rich ones, including the United States. There are technological and alternative supply fixes for everything else, but they will take time. Food shortages will hit early and will continue while the world’s farms adjust. There will be suffering and death from famine.

The curtailing of Russian exports will affect the United States in multiple ways, some of which might eventually turn out to be beneficial as the creative muscle is flexed.

In the utility industry, someone who is thinking big and boldly is Duane Highley, president and CEO of Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association in Denver.

Highley told Digital 360, the weekly webinar that emanates from Texas State University in San Marcos, the challenging problem of electricity storage could be solved not with lithium-ion batteries, but with iron-air batteries.

In its simplest form, an iron-air battery harnesses the process of rusting to store electricity. The process of rusting is used to produce power when it is exposed to oxygen captured on site. To charge the battery, an electric current reverses the process and returns the rust to iron.

Clearly, as Highley said, this won’t work for electric vehicles because of the weight of iron. But in utility operations, these batteries could offer the possibility of very long drawdown times --not just four hours, as with current lithium-ion batteries. And there is plenty of iron stateside.

Another Highley concept is that instead of dealing with all the complexities of transporting hydrogen, it should be stored as ammonia, which is more easily handled.

This isn’t magical thinking, but the kind of thinking which will lead us back to normal -- someday.

Politicians should stop the happy talk and tell us what we are facing.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C

It all depends on what you mean by ‘new’

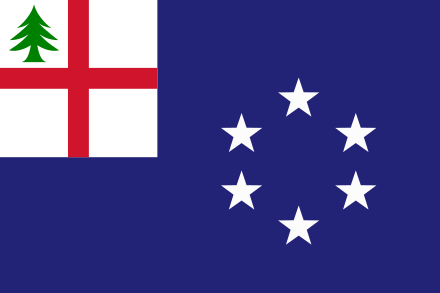

The New England Flag.

“New England is the illegitimate child of Old England….It is England and Scotland again in miniature and in childhood.’’

Calvin Colton, in Manual for Emigrants to America (1832)

xxx

“Of course what the man from Mars will find out first about New England is that it is neither new nor very much like England.’’

— John Gunther, in Inside U.S.A. (1947)

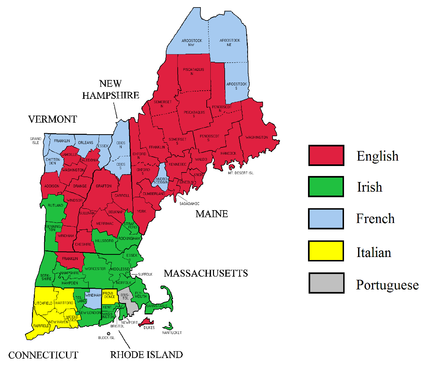

New England by background ethnicity

Better go by land

“River Currents” (oil on panel), by Cambridge, Mass.-based artist Wendy Prellwitz at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

Go Green Airport! fight Putin by shrinking your car

In Green Airport’s terminal lobby

— Photo by Antony-22

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s at least some good news -- locally. After years in which businesses and individuals have pleaded for nonstop air service between Rhode Island T.F. Green International Airport and the West Coast, Breeze Airways has announced that it will start twice-a-week service to Los Angeles in late June. The initial plan is only for summer service, but obviously that would change fast if demand shows the need for it to be year-round. I think that will happen. T.F. Green serves a large and densely populated area and is a pleasant alternative to braving the nasty traffic to Boston’s Logan International Airport.

Other new, twice-weekly destinations to be offered soon will be Columbus, Jacksonville, Savannah and Richmond, though Savannah will, like L.A., be summer-only to start.

Kudos to the folks at the Rhode Island Airport Corporation for pulling this off.

However, given the international situation, I doubt that new flights from Green, or indeed other airports, to foreign places are in the offing.

With a mass-murdering tyrant on the loose in Europe and, as a result, aviation and other fuel prices likely to rise even more; a recession possible, and COVID still hovering, all plans can be seen as even more imaginary than usual these days.

On those fuel prices, will Americans finally embrace smaller, fuel-efficient gasoline-powered cars and/or electric or hybrid cars instead of gas-guzzling pickup trucks and SUVs (which most people buy on credit)? Probably not….

If you want to make a patriotic gesture, get a smaller car.

1957 Heinkel Kabine bubble car

— Photo by Lothar Spurzem

When the worst of the current crisis is over, Congress should (but probably won’t have courage to) raise the federal gas tax from its present 18.4 cents a gallon -- set in 1993! -- to discourage gasoline-fueled driving, accelerate electric-vehicle use and use some of the money to aid lower-income people to deal with higher energy costs; the last thing was done in the 2008-2009 recession.

Federal payments to individuals under the Biden administration’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan last year have softened the blow: Far more people than usual have hefty savings. (The law of unintended consequences!)

Raising the gas tax would not only reduce the power of tyrannical and corrupt petrostates such as Russia and Saudi Arabia, whose fossil-fuel sales finance their crimes; it would also weaken over time the pricing power of American oil companies, which are now gleefully profiteering from the world crisis.

America would be in safer shape today if we had raised the gas tax long ago.

Total average U.S. state and federal gasoline taxes were 52 cents a gallon in 2019, compared to an average of $2.24 in other industrialized countries.

Oh, yes. There’s also that not-very-slow-moving catastrophe called global warming from burning fossil fuel, which we’ll still have to do lots of for some years to come. And indeed, for a couple of years we’ll probably have to extract more U.S. oil and gas than before the current world security crisis, made possible, ironically, in part by our addiction to fossil fuel.

Of course, the gasoline-cost surge will also encourage a reversal in the back-to-the office migration that has accompanied the waning (for now) of the COVID pandemic. Far too many Americans live in exurbs and suburbs far from their workplaces, and they drive gas-guzzlers. Putin has given them a good reason to go back to Zooming, in a new blow to downtowns

xxx

Note: The cost of energy from wind-power has gone up 0 percent since the current energy crisis started.

‘Feelings that art can restore’

“Multiple Phantasms” (encaustic wax, Fiber Clay, slinky), by Cheshire, Conn.-based artist Ruth Sack.

She says:

“Phantasmagoria: A bizarre or fantastic combination, collection, or assemblage.

“I slid down the tongue of a giant monster and emerged exultant. The monster was a play structure by Niki de Sainte Phalle called ‘Golem.’ I have since created my own whimsical artworks in order to spark that same thrill. The sculptures in this exhibit are inspired by Saint Phalle in pursuit of that excitement. I am as thrilled moving through a gigantic sculpture as I am when making a piece of art that delights me. These are the sort of feelings that have been quashed by the pandemic. These are the sort of feelings that art can restore.

“These works are part of a series called ‘Phantasmagoria.’ They have evolved from earlier coiled sculptures that evoked letterforms and primitive symbols. With the addition of organic shapes and detailed patterns, these pieces started to resemble lifelike characters. Each sculpture appears to be transitioning from an abstract form into an animated figure. This metamorphosis can summon thoughts of mythology and contemporary tales.’’

In Cheshire, from left to right: Cheshire Town Hall, Congregational Church, Historical Society, and Civil War memorial. The town also has a large bomb shelter under an AT&T tower. Given Russian mass murderer Putin’s tendencies, it may come in handy.

Roaring Brook Falls in Cheshire.

David Warsh: Knowledge and skepticism about the causes of inflation

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

In their introduction to the conference volume Knowledge and Skepticism, its editors wrote that there are two main questions worth asking in epistemology. What is knowledge? And, do we have any of it? Their formulation has often come to mind these days in connection with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but it has also welled-up in my thinking in connection with a very different matter, the phenomenon of inflation.

Charles Goodhart is a central banker’s expert on central banking. Having completed his PhD at Harvard University, in 1963, he worked for seventeen years as an adviser to the Bank of England on domestic monetary policy, during the tumultuous but ultimately successful battles in Britain and the United States against global inflation, all the while pursuing a thorough examination of the rationale for bank regulation in the first place.

In The Evolution of Central Banking (1988), he traced the history of the most important and least understood regulatory institution of modern government, and for the next thirty years remained in the forefront of the discussion of supervision of the world banking system.

Then, in 2020, with Manoj Pradhan, the 84-year-old Goodhart published The Great Demographic Reversal: Ageing Societies, Waning Inequality, and an Inflation Revival, arguing that that, owing to declining fertility rates in China and the West, the coronavirus pandemic has marked a watershed between the deflationary forces of the last thirty or forty years and a coming twenty years or so of rising prices. A headline of a recent story on the front page of The Wall Street Journal conveyed the story:

Will Inflation Stay High for Decades? One Influential Economist Says Yes

Charles Goodhart sees an era of inexpensive labor giving way to years of worker shortages—and higher prices. Central bankers around the world are listening.

Goodhart predicts that inflation in advanced economies will settle at 3 percent to 4 percent around the end of 2022 and remain at that level for decades, wrote WSJ reporter Tom Fairless, as opposed to about 1.5 percent in the decade before the pandemic, with interest rates correspondingly higher. The Black Death, a 14th Century pandemic, had triggered a similar quarter-century of soaring wages and rising prices, he observed. You can read Fairless’s story yourself, thanks to this free link.

The question is, if Goodhart is right, what should central bankers do about it? Ever since he first presented his findings to a meeting of central bankers in 2016, monetary policy specialists representing various interests and points of view have been arguing about it. “Lower for Longer, ‘‘the latest report of the technical advisory committee of the European Systemic Risk Boars, takes Goodhart’s argument into account and differs sharply.

Among the experts exists a 400- year-old difference of opinion, known by different names at different times, of which Keynesian and Monetarist or Freshwater Saltwater are only the most recent. Some conclude that making appropriate policy is relatively easy: Simply require the central bank to control the supply of money. Others say central bankers’ job is difficult. John Greenwood and Steve H. Hanke, of Johns Hopkins University, put it this way in a recent Journal of Corporate Finance,

There have always been two types of explanations for inflation: ad hoc explanations and monetary explanations. Historically, the ad hoc explanations have been in terms of special factors present on particular occasions: commodity price increases due to bad harvests, supply disruptions due to restrictions on international trade, profiteers or monopolists holding back scarce goods, or trades unions pushing up wages leading to a wage-price spiral or cost-push pressures, and so on in great variety. Even the widely used aggregate demand-aggregate supply model is a species of ad hoc explanation in the sense that it relies on idiosyncratic factors driving estimates of the output gap or special factors affecting the supply of labor or productivity.

The monetary explanations for inflation have focused on increases in the quantity of money: either new discoveries of gold and silver in centuries past, or fiat money creation by the banking system or by the central bank in modern times.

I am an economic journalist, not an economist, and to my mind, there has always seemed something a circular about the shorthand explanation of rising prices, to the effect that “inflation is a matter of too much money chasing too few goods.” By making “rising prices” of goods synonymous with “inflation” of the quantity of money, the language of the shorthand assumes its own truth, and gives short shrift to the changing nature of “goods.” What about the declining fertility rate in China and the West?

As a journalist, I’ve come to think that a more revealing formulation of the difference of opinion about rising (or falling) prices is to be found in Joseph Schumpeter’s History of Economic Analysis (1954), where the economist distinguished between real and monetary analysis. Real analysis, Schumpeter wrote, is old as Aristotle. It “proceeds from the principle that all the essential phenomena of economic life are capable of being described in terms of goods and services, of decisions about them, and relations between them. Money enters the picture only in the modest role of a technical device that had been adopted in order to facilitate transactions,” and, occasionally, in the central role of what are described as “monetary disorders.”

Monetary analysis, Schumpeter continued, denies that money is of secondary importance in economic affairs., “We need only observe the course of events during and after the California gold discoveries to solidify ourselves that these discoveries were responsible for a great deal more than a change in the unit with which values are expressed,” he added, observing that money serves as a store of value as well as a means of transacting business.

Nor have we any difficulty in realizing – as A. Smith did – that the development of an efficient banking system may make a lot of difference in the development of a country’s wealth.

Schumpeter did not have an especially high opinion of Adam Smith!

As it happens, I wrote a book about all this forty years ago. As a magazine writer in New York, I had come across a 700-year index of the cost of living in a certain fashion in England. It showed two decades-long periods of steadily rising prices, one in the 16th Century, another in the 18th, both of which eventually leveled off, never returning to their prior levels. So I wrote in 1975 that the rising prices of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s, too, would probably level off one day, though I didn’t venture why or when, much less mention Paul Volcker, the Federal Reserve Board chairman in 1979-1987.

My interest piqued, I spent a year in the New York Public Library unburdening myself of (some of) my ignorance, before turning back to the task of earning a living, this time as a newspaperman in Boston. By then I was more interested in the history of technology and government. Money and banking? Yawn! The Idea of Economic Complexity finally emerged in 1984, with nothing more to unify those ad hoc accounts of rising prices than the word complexity; intuitively appealing, perhaps, but analytically empty. It was a shaggy little book, in James Fallows’s apt description, politely received and quickly forgotten.

But before it was, Charles P. Kindleberger replied to a note I had written to say that I was entirely right that complexity does not communicate itself to economists, “at least not to this economist.” Kindleberger and I gradually became friends, and gradually I learned how little I understood how about the languages in which economist wrote for one another. Since then my knowledge of economics has increased to include, for example, the distinction between real and monetary analysis, and so has my admiration for what professional economist have achieved in the 250 years they have been doing business together. But then so have my doubts that economists have yet learned all there is to know about the understanding their science can produce. And, suddenly, primers on “inflation” are back in the news for the first time since in forty years.

So I plan to write a few pieces, half a dozen in all, one after another, about what I have learned about what I was trying to say forty years ago, anchoring each in a particular book or article that opened my eyes. I am not a true skeptic in the philosophers’ senses; don’t think that nobody knows anything: I think that economists know a lot. But I believe that they are still learning, that there are things that economists don’t yet know how to say, and that journalists can contribute to the conversation.

If you are looking for state-of-the-art knowledge, read Charles Goodhart. If you are interested in informed speculation, keep reading here. Better yet, do both. A lot of adventure lies ahead.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

Liz Szabo: COVID's silver lining may be breakthroughs against other severe diseases

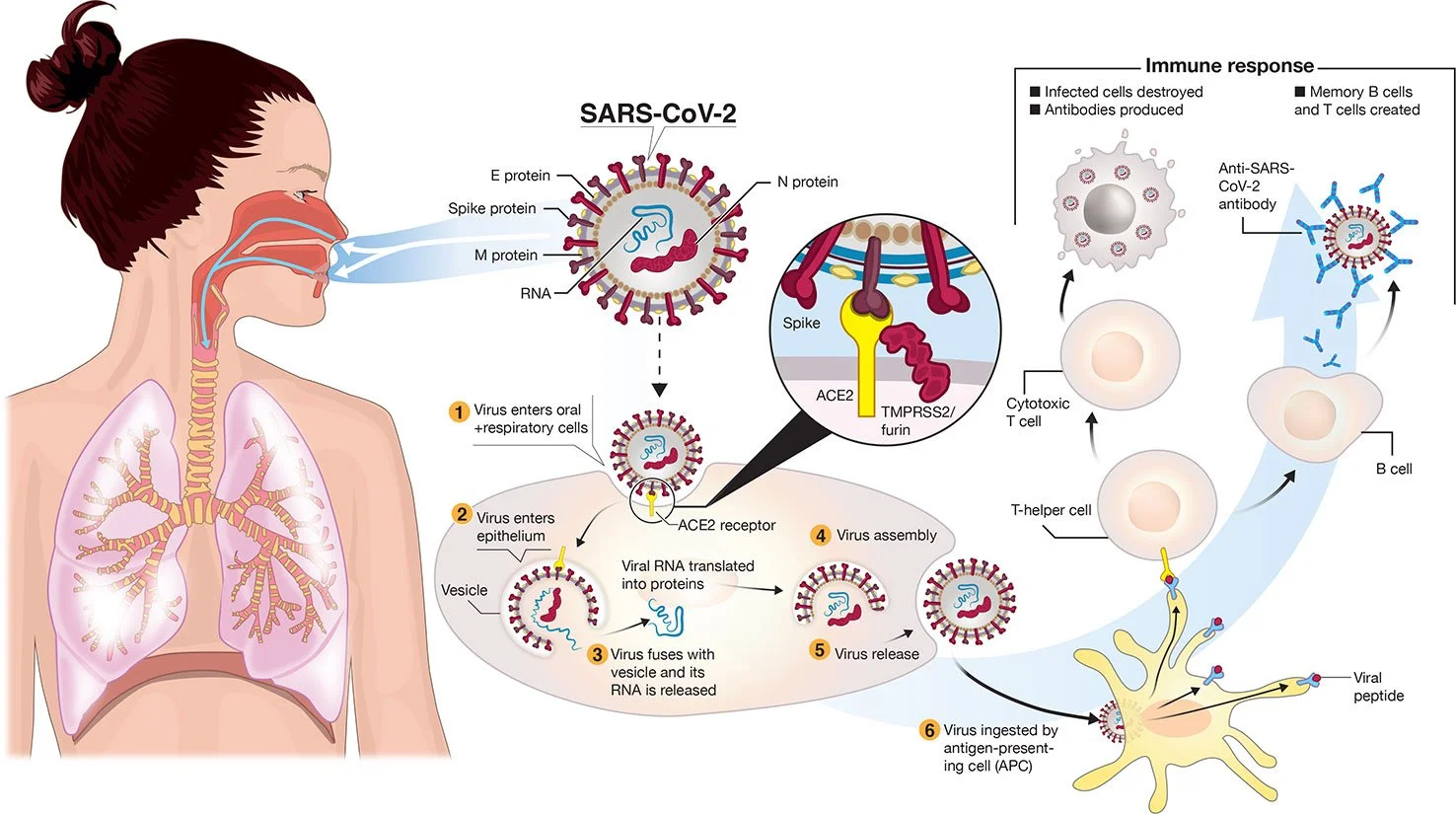

Transmission and life-cycle of SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19. 2/furin. A simplified depiction of the life cycle of the virus is shown along with potential immune responses elicited.

— Colin D. Funk, Craig Laferrière, and Ali Ardakani. Graphic by Ian Dennis - http://www.iandennisgraphics.com

“It’s not either/or. We’ve created this artificial dichotomy about how we think about these viruses. But we always put out a mixture of both” when we breathe, cough and sneeze.

— Dr. Michael Klompas, a professor at Harvard Medical School and infectious- disease doctor.

xxx

“There is a lot of frustration about being written off by the medical community, being told that it’s all in one’s head, that they just need to see a psychiatrist or go to the gym.’’

— Dr. David Systrom, a pulmonary and critical-care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston.

The billions of dollars invested in COVID-19 vaccines and research so far are expected to yield medical and scientific dividends for decades, helping doctors battle influenza, cancer, cystic fibrosis and far more diseases.

“This is just the start,” said Dr. Judith James, vice president of clinical affairs for the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. “We won’t see these dividends in their full glory for years.”

Building on the success of mRNA vaccines for covid, scientists hope to create mRNA-based vaccines against a host of pathogens, including influenza, Zika, rabies, HIV, and respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, which hospitalizes 3 million children under age 5 each year worldwide.

Researchers see promise in mRNA to treat cancer, cystic fibrosis and rare, inherited metabolic disorders, although potential therapies are still many years away.

Pfizer and Moderna worked on mRNA vaccines for cancer long before they developed covid shots. Researchers are now running dozens of clinical trials of therapeutic mRNA vaccines for pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, and melanoma, which frequently responds well to immunotherapy.

Companies looking to use mRNA to treat cystic fibrosis include ReCode Therapeutics, Arcturus Therapeutics, and Moderna and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, which are collaborating. The companies’ goal is to correct a fundamental defect in cystic fibrosis, a mutated protein.

Rather than replace the protein itself, scientists plan to deliver mRNA that would instruct the body to make the normal, healthy version of the protein, said David Lockhart, ReCode’s president and chief science officer.

None of these drugs is in clinical trials yet.

That leaves patients such as Nicholas Kelly waiting for better treatment options.

Kelly, 35, was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis as an infant and has never been healthy enough to work full time. He was recently hospitalized for 2½ months due to a lung infection, a common complication for the 30,000 Americans with the disease. Although novel medications have transformed the lives of most people with CF, they don’t work in 10% of patients. About one-third of patients who don’t benefit from the new medications are Black and/or Hispanic, said JP Clancy, vice president of clinical research for the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

“Nobody wants to be hospitalized,” said Kelly, who lives in Cleveland. “If something could decrease my symptoms even 10%, I would try it.”

Predicting Which COVID Patients Are Most Likely to Die

Ambitious scientific endeavors have provided technological windfalls for consumers in the past; the race to land on the moon in the 1960s led to the development of CT scanners and MRI machines, freeze-dried food, wireless headphones, water purification systems, and the computer mouse.

Likewise, funding for AIDS research has benefited patients with a variety of diseases, said Dr. Carlos del Rio, a professor of infectious diseases at Emory University School of Medicine. Studies of HIV led to the development of better drugs for hepatitis C and cytomegalovirus, or CMV; paved the way for successful immunotherapies in cancer; and speeded the development of covid vaccines.

Over the past two years, medical researchers have generated more than 230,000 medical journal articles, documenting studies of vaccines, antivirals, and other drugs, as well as basic research into the structure of the virus and how it evades the immune system.

Dr. Michelle Monje, a professor of neurology at Stanford University, has found similarities in the cognitive side effects caused by COVID and a side effect of cancer therapy often called “chemo brain.” Learning more about the root causes of these memory problems, Monje said, could help scientists eventually find ways to prevent or treat them.

James hopes that computer technology used to detect COVID will improve the treatment of other diseases. For example, researchers have shown that cell-phone apps can help detect potential covid cases by monitoring patients’ self-reported symptoms. James said she wonders if the same technology could predict flare-ups of autoimmune diseases.

“We never dreamed we could have a PCR test that could be done anywhere but a lab,” James said. “Now we can do them at a patient’s bedside in rural Oklahoma. That could help us with rapid testing for other diseases.”

One of the most important pandemic breakthroughs was the discovery that 15 to 20 percent of patients over 70 who die of COVID have rogue antibodies that disable a key part of the immune system. Although antibodies normally protect us from infection, these “autoantibodies” attack a protein called interferon that acts as a first line of defense against viruses.

By disabling key immune fighters, autoantibodies against interferon allow the coronavirus to multiply wildly. The massive infection that results can lead the rest of the immune system to go into hyperdrive, causing a life-threatening “cytokine storm,” said Dr. Paul Bastard, a researcher at Rockefeller University.

The discovery of interferon-targeting antibodies “certainly changed my way of thinking at a broad level,” said E. John Wherry, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Institute for Immunology, who was not involved in the studies. “This is a paradigm shift in immunology and in COVID.”

Antibodies that disable interferon may explain why a fraction of patients succumb to viral diseases, such as influenza, while most recover, said Dr. Gary Michelson, founder and co-chair of Michelson Philanthropies, a nonprofit that funds medical research and recently gave Bastard its inaugural award in immunology.

The discovery “goes far beyond the impact of COVID-19,” Michelson said. “These findings may have implications in treating patients with other infectious diseases” such as the flu.

Bastard and colleagues have also found that one-third of patients with dangerous reactions to yellow fever have autoantibodies against interferon.

International research teams are now looking for such autoantibodies in patients hospitalized by other viral infections, including chickenpox, influenza, measles, respiratory syncytial virus, and others.

Overturning Dogma

For decades, public health officials created policies based on the assumption that viruses spread in one of two ways: either through the air, like measles and tuberculosis, or through heavy, wet droplets that spray from our mouths and noses, then quickly fall to the ground, like influenza.

For the first 17 months of the covid pandemic, the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said the coronavirus spread through droplets and advised people to wash their hands, stand 6 feet apart, and wear face coverings. As the crisis wore on and evidence accumulated, researchers began to debate whether the coronavirus might also be airborne.

Today it’s clear that the coronavirus — and all respiratory viruses — spread through a combination of droplets and aerosols, said Dr. Michael Klompas, a professor at Harvard Medical School and infectious disease doctor.

“It’s not either/or,” Klompas said. “We’ve created this artificial dichotomy about how we think about these viruses. But we always put out a mixture of both” when we breathe, cough, and sneeze.

Knowing that respiratory viruses commonly spread through the air is important because it can help health agencies protect the public. For example, high-quality masks, such as N95 respirators, offer much better protection against airborne viruses than cloth masks or surgical masks. Improving ventilation, so that the air in a room is completely replaced at least four to six times an hour, is another important way to control airborne viruses.

Still, Klompas said, there’s no guarantee that the country will handle the next outbreak any better than this one. “Will we do a better job fighting influenza because of what we’ve learned?” Klompas said. “I hope so, but I’m not holding my breath.”

Fighting Chronic Disease

Lauren Nichols, 32, remembers exactly when she developed her first covid symptoms: March 10, 2020.

It was the beginning of an illness that has plagued her for nearly two years, with no end in sight. Although Nichols was healthy before developing what has become known as “long COVID,” she deals with dizziness, headaches, and debilitating fatigue, which gets markedly worse after exercise. She has had shingles — a painful rash caused by the reactivation of the chickenpox virus — four times since her covid infection.

Six months after testing positive for COVID, Nichols was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis, or ME/CFS, which affects more than 1 million Americans and causes many of the same symptoms as COVID. There are few effective treatments for either condition.

In fact, research suggests that “the two conditions are one and the same,” said Dr. Avindra Nath, clinical director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, part of the National Institutes of Health. The main difference is that people with long COVID know which virus caused their illness, while the precise virus behind most cases of chronic fatigue is unknown, Nath said.

Advocates of patients with long COVID want to ensure that future research — including $1.15 billion in targeted funding from the NIH — benefits all patients with chronic, post-viral diseases.

“Anything that shows promise in long covid will be immediately trialed in ME/CFS,” said Jarred Younger, director of the Neuroinflammation, Pain and Fatigue Laboratory at the University of Alabama-Birmingham.

Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome have felt a kinship with long COVID patients, and vice versa, not just because they experience the same baffling symptoms, but also because both have struggled to obtain compassionate, appropriate care, said Nichols, vice president of Body Politic, an advocacy group for people with long COVID and other chronic or disabling conditions.

“There is a lot of frustration about being written off by the medical community, being told that it’s all in one’s head, that they just need to see a psychiatrist or go to the gym,” said Dr. David Systrom, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

That sort of ignorance seems to be declining, largely because of increasing awareness about long COVID, said Emily Taylor, vice president of advocacy and engagement at Solve M.E., an advocacy group for people with post-infectious chronic illnesses. Although some doctors still refuse to believe long covid is a real disease, “they’re being drowned out by the patient voices,” Taylor said.

A new study from the National Institutes of Health, called RECOVER (Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery), is enrolling 15,000 people with long covid and a comparison group of nearly 3,000 others who haven’t had covid.

“In a very dark cloud,” Nichols said, “a silver lining coming out of long covid is that we’ve been forced to acknowledge how real and serious these conditions are.”

Liz Szabo is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

A place to be free

“We learned the shocking truth that ‘home’ isn’t necessarily a certain spot on earth. It must be a place where you can ‘feel’ at home, which means ‘free’ to us.’’

— Maria Augusta von Trapp, in The Story of the Trapp Family Singers (made famous by The Sound of Music). In 1938 the family fled the Nazis, who had taken over Austria, and eventually settled in Stowe, Vt.

The earth in a few years?

“Blue Marble Orb” (15 inches round, encaustic, mixed media on milled pine), by Ashland, Mass.-based artist Pamela Dorris DeJong.

She says:

“After painting land and waterscapes for many years I realized that I could put forth healing energy towards the earth and our oceans. Healing can occur through painting, meditation, education, sharing the message through the image itself, and explanation of the intent.’’

Built in 1832 as an inn (now it’s just a restaurant) by Captain John Stone, to capitalize on the new Boston and Worcester Railroad, The Railroad House, later renamed John Stone's Inn, and now known as Stone's Public House, is in the center of Ashland.

Stone's is said to be haunted by various ghosts. The story of one of them: Captain Stone is said to have accidentally killed a New York salesman named Mike McPherson when he hit him on the head with a pistol when he suspected McPherson of cheating at poker. Stone and three friends with whom he had been playing allegedly swore to keep the killing secret and buried the salesman's body in the inn's basement. The legend contends that the ghosts of the salesman and the three other players involved all roam the inn. But no body has ever been found.